Army Of Brandenburg-Prussia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the

The army of Prussia grew out of the united armed forces created during the reign of Elector Frederick William of

The army of Prussia grew out of the united armed forces created during the reign of Elector Frederick William of  By 1643–44, the developing army numbered only 5,500 troops, including 500

By 1643–44, the developing army numbered only 5,500 troops, including 500

Brandenburg-Prussia's new army survived its trial by fire through victory in the 1656 Battle of Warsaw, during the

Brandenburg-Prussia's new army survived its trial by fire through victory in the 1656 Battle of Warsaw, during the

Frederick I was succeeded by his son, Frederick William I (1713–1740), the "Soldier-King" obsessed with the army and achieving self-sufficiency for his country. The new king dismissed most of the artisans from his father's court and granted military officers precedence over court officials. Ambitious and intelligent young men began to enter the military instead of law and administration.

Frederick I was succeeded by his son, Frederick William I (1713–1740), the "Soldier-King" obsessed with the army and achieving self-sufficiency for his country. The new king dismissed most of the artisans from his father's court and granted military officers precedence over court officials. Ambitious and intelligent young men began to enter the military instead of law and administration.

Frederick William I was succeeded by his son, Frederick II (1740–86). Frederick immediately disbanded the expensive Potsdam Giants and used their funding to create seven new regiments and 10,000 troops. The new king also added sixteen battalions, five squadrons of

Frederick William I was succeeded by his son, Frederick II (1740–86). Frederick immediately disbanded the expensive Potsdam Giants and used their funding to create seven new regiments and 10,000 troops. The new king also added sixteen battalions, five squadrons of

Frederick's maneuvers were unsuccessful against the Russians in the bloody

Frederick's maneuvers were unsuccessful against the Russians in the bloody

The first

The first

The defeat of the disorganized army shocked the Prussian establishment, which had largely felt invincible after the Frederician victories. While Baron vom Stein and Prime Minister

The defeat of the disorganized army shocked the Prussian establishment, which had largely felt invincible after the Frederician victories. While Baron vom Stein and Prime Minister  The generals of the army were completely overhauled — of the 143 Prussian generals in 1806, only Blücher and Tauentzien remained by the

The generals of the army were completely overhauled — of the 143 Prussian generals in 1806, only Blücher and Tauentzien remained by the

The reformers and much of the public called for Frederick William III to ally with the

The reformers and much of the public called for Frederick William III to ally with the

The

The  By the middle of the 19th century, Prussia was seen by many German liberals as the country best-suited to unify the many German states, but the conservative government used the army to repress liberal and democratic tendencies during the 1830s and 1840s. Liberals resented the usage of the army in essentially police actions. King

By the middle of the 19th century, Prussia was seen by many German liberals as the country best-suited to unify the many German states, but the conservative government used the army to repress liberal and democratic tendencies during the 1830s and 1840s. Liberals resented the usage of the army in essentially police actions. King  The government submitted Roon's army reform bill in February 1860. Parliament opposed many of its provisions, especially the weakening of the ''Landwehr'', and proposed a revised bill that did away with many of the government's desired reforms. The Finance Minister, Patow, abruptly withdrew the bill on 5 May and instead simply requested a provisional budgetary increase of 9 million thalers, which was granted. William had already begun creating 'combined regiments' to replace the ''Landwehr'', a process which increased after Patow acquired the additional funds. Although parliament was opposed to these actions, William maintained the new regiments with the guidance of

The government submitted Roon's army reform bill in February 1860. Parliament opposed many of its provisions, especially the weakening of the ''Landwehr'', and proposed a revised bill that did away with many of the government's desired reforms. The Finance Minister, Patow, abruptly withdrew the bill on 5 May and instead simply requested a provisional budgetary increase of 9 million thalers, which was granted. William had already begun creating 'combined regiments' to replace the ''Landwehr'', a process which increased after Patow acquired the additional funds. Although parliament was opposed to these actions, William maintained the new regiments with the guidance of

The Prussian Army crushed

The Prussian Army crushed

The

The

The Prussian-style war of movement and quick strikes was well-suited for campaigns using the developed infrastructure of Western and Central Europe, such as in the wars of unification, but failed when the

The Prussian-style war of movement and quick strikes was well-suited for campaigns using the developed infrastructure of Western and Central Europe, such as in the wars of unification, but failed when the

Grosser-Generalstab.de

Die Regimenter und Bataillone der deutschen Armee

Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library

{{Standing German armies in the Holy Roman Empire Disbanded armies Prussian Army 17th-century establishments in Prussia Military units and formations established in 1701 Military units and formations disestablished in 1919

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

of the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Re ...

. It became vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia

Brandenburg-Prussia (german: Brandenburg-Preußen; ) is the historiographic denomination for the early modern realm of the Brandenburgian Hohenzollerns between 1618 and 1701. Based in the Electorate of Brandenburg, the main branch of the Hohenz ...

as a European power.

The Prussian Army had its roots in the core mercenary

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any o ...

forces of Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a states of Germany, state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an ar ...

during the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (80 ...

of 1618–1648. Elector Frederick William developed it into a viable standing army

A standing army is a permanent, often professional, army. It is composed of full-time soldiers who may be either career soldiers or conscripts. It differs from army reserves, who are enrolled for the long term, but activated only during wars or n ...

, while King Frederick William I of Prussia

Frederick William I (german: Friedrich Wilhelm I.; 14 August 1688 – 31 May 1740), known as the "Soldier King" (german: Soldatenkönig), was King in Prussia and Elector of Brandenburg from 1713 until his death in 1740, as well as Prince of Neuch ...

dramatically increased its size and improved its doctrines. King Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the Sil ...

, a formidable battle commander, led the disciplined Prussian troops to victory during the 18th-century Silesian Wars

The Silesian Wars (german: Schlesische Kriege, links=no) were three wars fought in the mid-18th century between Prussia (under King Frederick the Great) and Habsburg Austria (under Archduchess Maria Theresa) for control of the Central European ...

and greatly increased the prestige of the Kingdom of Prussia.

The army had become outdated by the beginning of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

defeated Prussia in the War of the Fourth Coalition

The Fourth Coalition fought against Napoleon's French Empire and were defeated in a war spanning 1806–1807. The main coalition partners were Prussia and Russia with Saxony, Sweden, and Great Britain also contributing. Excluding Prussia, s ...

in 1806. However, under the leadership of Gerhard von Scharnhorst

Gerhard Johann David von Scharnhorst (12 November 1755 – 28 June 1813) was a Hanoverian-born general in Prussian service from 1801. As the first Chief of the Prussian General Staff, he was noted for his military theories, his reforms of the Pru ...

, Prussian reformers began modernizing the Prussian Army, which contributed greatly to the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

during the War of the Sixth Coalition

In the War of the Sixth Coalition (March 1813 – May 1814), sometimes known in Germany as the Wars of Liberation, a coalition of Austria, Prussia, Russia, Spain, the United Kingdom, Portugal, Sweden, and a number of German States defeated F ...

. Conservatives halted some of the reforms, however, and the Prussian Army subsequently became a bulwark of the conservative Prussian government.

In the 19th century, the Prussian Army fought successful wars against Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark

...

, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, allowing Prussia to unify Germany, aside from Austria, establishing the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

in 1871. The Prussian Army formed the core of the Imperial German Army

The Imperial German Army (1871–1919), officially referred to as the German Army (german: Deutsches Heer), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the l ...

, which was replaced by the ''Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' () was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first years of the Third Reich. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshaped ...

'' after World War I.

The Great Elector

Creation of the army

The army of Prussia grew out of the united armed forces created during the reign of Elector Frederick William of

The army of Prussia grew out of the united armed forces created during the reign of Elector Frederick William of Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a states of Germany, state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an ar ...

(1640–1688). Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, also , german: Haus Hohenzollern, , ro, Casa de Hohenzollern) is a German royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) dynasty whose members were variously princes, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzollern, Brandenb ...

Brandenburg-Prussia

Brandenburg-Prussia (german: Brandenburg-Preußen; ) is the historiographic denomination for the early modern realm of the Brandenburgian Hohenzollerns between 1618 and 1701. Based in the Electorate of Brandenburg, the main branch of the Hohenz ...

had primarily relied upon ''Landsknecht

The (singular: , ), also rendered as Landsknechts or Lansquenets, were Germanic mercenaries used in pike and shot formations during the early modern period. Consisting predominantly of pikemen and supporting foot soldiers, their front line wa ...

'' mercenaries

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any o ...

during the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (80 ...

, in which Brandenburg was devastated. Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

and Imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* Imperial, Texa ...

forces occupied the country. In the spring of 1644, Frederick William started building a standing army

A standing army is a permanent, often professional, army. It is composed of full-time soldiers who may be either career soldiers or conscripts. It differs from army reserves, who are enrolled for the long term, but activated only during wars or n ...

through conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

to better defend his state.

By 1643–44, the developing army numbered only 5,500 troops, including 500

By 1643–44, the developing army numbered only 5,500 troops, including 500 musketeer

A musketeer (french: mousquetaire) was a type of soldier equipped with a musket. Musketeers were an important part of early modern warfare particularly in Europe as they normally comprised the majority of their infantry. The musketeer was a pre ...

s in Frederick William's bodyguard.Citino, p. 6. The elector's confidant Johann von Norprath recruited forces in the Duchy of Cleves

The Duchy of Cleves (german: Herzogtum Kleve; nl, Hertogdom Kleef) was a State of the Holy Roman Empire which emerged from the medieval . It was situated in the northern Rhineland on both sides of the Lower Rhine, around its capital Cleves and ...

and organized an army of 3,000 Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

and German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

soldiers in the Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

by 1646. Garrisons were also slowly augmented in Brandenburg and the Duchy of Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (german: Herzogtum Preußen, pl, Księstwo Pruskie, lt, Prūsijos kunigaikštystė) or Ducal Prussia (german: Herzogliches Preußen, link=no; pl, Prusy Książęce, link=no) was a duchy in the Prussia (region), region of P ...

. Frederick William sought assistance from France, the traditional rival of Habsburg Austria The term Habsburg Austria may refer to the lands ruled by the Austrian branch of the Habsburgs, or the historical Austria. Depending on the context, it may be defined as:

* The Duchy of Austria, after 1453 the Archduchy of Austria

* The ''Erbland ...

, and began receiving French subsidies. He based his reforms on those of Louvois, the War Minister

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

of King Louis XIV of France

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Versa ...

.Koch, p. 59. The growth of his army allowed Frederick William to achieve considerable territorial acquisitions in the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (german: Westfälischer Friede, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought peac ...

, despite Brandenburg's relative lack of success during the war.

The provincial estates desired a reduction in the army's size during peacetime, but the elector avoided their demands through political concessions, evasion and economy. In the 1653 Brandenburg Recess

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an area of 29,480 square ...

between Frederick William and the estates of Brandenburg, the nobility provided the sovereign with 530,000 thaler

A thaler (; also taler, from german: Taler) is one of the large silver coins minted in the states and territories of the Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburg monarchy during the Early Modern period. A ''thaler'' size silver coin has a diameter of ...

s in return for affirmation of their privileges. The ''Junkers'' thus cemented their political power at the expense of the peasantry. Once the elector and his army were strong enough, Frederick William was able to suppress the estates of Cleves, Mark

Mark may refer to:

Currency

* Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, the currency of Bosnia and Herzegovina

* East German mark, the currency of the German Democratic Republic

* Estonian mark, the currency of Estonia between 1918 and 1927

* Fi ...

and Prussia.

Frederick William attempted to professionalize his soldiers during a time when mercenaries were the norm. In addition to individually creating regiments and appointing colonels, the elector imposed harsh punishments for transgressions, such as punishing by hanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging i ...

for looting

Looting is the act of stealing, or the taking of goods by force, typically in the midst of a military, political, or other social crisis, such as war, natural disasters (where law and civil enforcement are temporarily ineffective), or rioting. ...

, and running the gauntlet

Running is a method of terrestrial locomotion allowing humans and other animals to move rapidly on foot. Running is a type of gait characterized by an aerial phase in which all feet are above the ground (though there are exceptions). This is ...

for desertion

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or post without permission (a pass, liberty or leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with unauthorized absence (UA) or absence without leave (AWOL ), which ar ...

. Acts of violence by officers against civilians resulted in decommission for a year. He developed a cadet institution for the nobility; although the upper class was resistant to the idea in the short term, the integration of the nobility into the officer corps

An officer is a person who holds a position of authority as a member of an armed force or uniformed service.

Broadly speaking, "officer" means a commissioned officer, a non-commissioned officer, or a warrant officer. However, absent contextu ...

allied them with the Hohenzollern monarchy in the long term.Koch, p. 60. Field Marshals of Brandenburg-Prussia included Derfflinger, John George II, Spaen and Sparr. The elector's troops traditionally were organized into disconnected provincial forces. In 1655, Frederick William began the unification of the various detachments by placing them under Sparr's overall command. Unification also increased through the appointment of ''Generalkriegskommissar'' Platen

A platen (or platten) is a flat platform with a variety of roles in printing or manufacturing. It can be a flat metal (or earlier, wooden) plate pressed against a medium (such as paper) to cause an impression in letterpress printing. Platen m ...

as head of supplies. These measures decreased the authority of the primarily mercenary colonels who had been so prominent during the Thirty Years' War.

Campaigns of the Great Elector

Brandenburg-Prussia's new army survived its trial by fire through victory in the 1656 Battle of Warsaw, during the

Brandenburg-Prussia's new army survived its trial by fire through victory in the 1656 Battle of Warsaw, during the Northern Wars

"Northern Wars" is a term used for a series of wars fought in northern and northeastern Europe from the 16th to the 18th century. An internationally agreed-on nomenclature for these wars has not yet been devised. While the Great Northern War is gen ...

. Observers were impressed with the discipline of the Brandenburger troops, as well as their treatment of civilians, which was considered more humane than that of their allies, the Swedish Army

The Swedish Army ( sv, svenska armén) is the land force of the Swedish Armed Forces.

History

Svea Life Guards dates back to the year 1521, when the men of Dalarna chose 16 young able men as body guards for the insurgent nobleman Gustav Vas ...

. Hohenzollern success enabled Frederick William to assume sovereignty over the Duchy of Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (german: Herzogtum Preußen, pl, Księstwo Pruskie, lt, Prūsijos kunigaikštystė) or Ducal Prussia (german: Herzogliches Preußen, link=no; pl, Prusy Książęce, link=no) was a duchy in the Prussia (region), region of P ...

in the 1657 Treaty of Wehlau

The Treaty of Bromberg (, Latin: Pacta Bydgostensia) or Treaty of Bydgoszcz was a treaty between John II Casimir of Poland and Elector Frederick William of Brandenburg-Prussia that was ratified at Bromberg (Bydgoszcz) on 6 November 1657. The trea ...

, by which Brandenburg-Prussia allied itself with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

. Despite having expelled Swedish forces from the territory, the elector did not acquire Vorpommern

Historical Western Pomerania, also called Cispomerania, Fore Pomerania, Front Pomerania or Hither Pomerania (german: Vorpommern), is the western extremity of the historic region of Pomerania forming the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, Weste ...

in the 1660 Treaty of Oliva

The Treaty or Peace of Oliva of 23 April (OS)/3 May (NS) 1660Evans (2008), p.55 ( pl, Pokój Oliwski, sv, Freden i Oliva, german: Vertrag von Oliva) was one of the peace treaties ending the Second Northern War (1655-1660).Frost (2000), p.183 ...

, as the balance of power had been restored.

In the early 1670s, Frederick William supported Imperial attempts to reclaim Alsace

Alsace (, ; ; Low Alemannic German/ gsw-FR, Elsàss ; german: Elsass ; la, Alsatia) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in eastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland. In 2020, it had ...

and counter the expansion of Louis XIV of France. Swedish troops invaded Brandenburg in 1674 while the bulk of the elector's forces were in Franconia's winter quarters. In 1675 Frederick William marched his troops northward and surrounded Wrangel's troops. The elector achieved his greatest victory in the Battle of Fehrbellin

The Battle of Fehrbellin was fought on June 18, 1675 (Julian calendar date, June 28th, Gregorian), between Swedish and Brandenburg-Prussian troops. The Swedes, under Count Waldemar von Wrangel (stepbrother of '' Riksamiral'' Carl Gustaf Wrange ...

; although a minor battle, it brought fame to the Brandenburg-Prussian Army and gave Frederick William the nickname "the Great Elector". After Sweden invaded Prussia in late 1678, Frederick William's forces expelled the Swedish invaders during the "Great Sleigh Drive

"The Great Sleigh Drive" (german: Die große Schlittenfahrt) from December 1678 to February 1679 was a daring and bold maneuver using sleighs by Frederick William, the Great Elector of Brandenburg-Prussia, to drive Swedish forces out of the Du ...

" of 1678–79; Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dum ...

compared the wintertime Swedish retreat to that of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

from Moscow.

Frederick William built the Hohenzollern army up to a peacetime size of 7,000 and a wartime size of 15,000–30,000. Its success in battle against Sweden and Poland increased Brandenburg-Prussia's prestige, while also allowing the Great Elector to pursue absolutist policies against estates and towns. In his political testament of 1667, the elector wrote, "Alliances, to be sure, are good, but forces of one's own still better. Upon them one can rely with more security, and a lord is of no consideration if he does not have means and troops of his own".

The growing power of the Hohenzollerns in Berlin led Frederick William's son and successor, Elector Frederick III (1688–1713), to proclaim the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Re ...

with himself as King Frederick I Frederick I may refer to:

* Frederick of Utrecht or Frederick I (815/16–834/38), Bishop of Utrecht.

* Frederick I, Duke of Upper Lorraine (942–978)

* Frederick I, Duke of Swabia (1050–1105)

* Frederick I, Count of Zoller ...

in 1701. Although he emphasized Baroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including t ...

opulence and the arts in imitation of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, u ...

, the new king recognized that the importance of the army and continued its expansion to 40,000 men.

The Soldier-King

Frederick I was succeeded by his son, Frederick William I (1713–1740), the "Soldier-King" obsessed with the army and achieving self-sufficiency for his country. The new king dismissed most of the artisans from his father's court and granted military officers precedence over court officials. Ambitious and intelligent young men began to enter the military instead of law and administration.

Frederick I was succeeded by his son, Frederick William I (1713–1740), the "Soldier-King" obsessed with the army and achieving self-sufficiency for his country. The new king dismissed most of the artisans from his father's court and granted military officers precedence over court officials. Ambitious and intelligent young men began to enter the military instead of law and administration. Conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

among the peasantry was more firmly enforced, based on the Swedish model. Frederick William I wore his simple blue military uniform at court, a style henceforth imitated by the rest of the Prussian court and his royal successors. In Prussia, pigtails replaced the full-bottomed wigs common at most German courts.

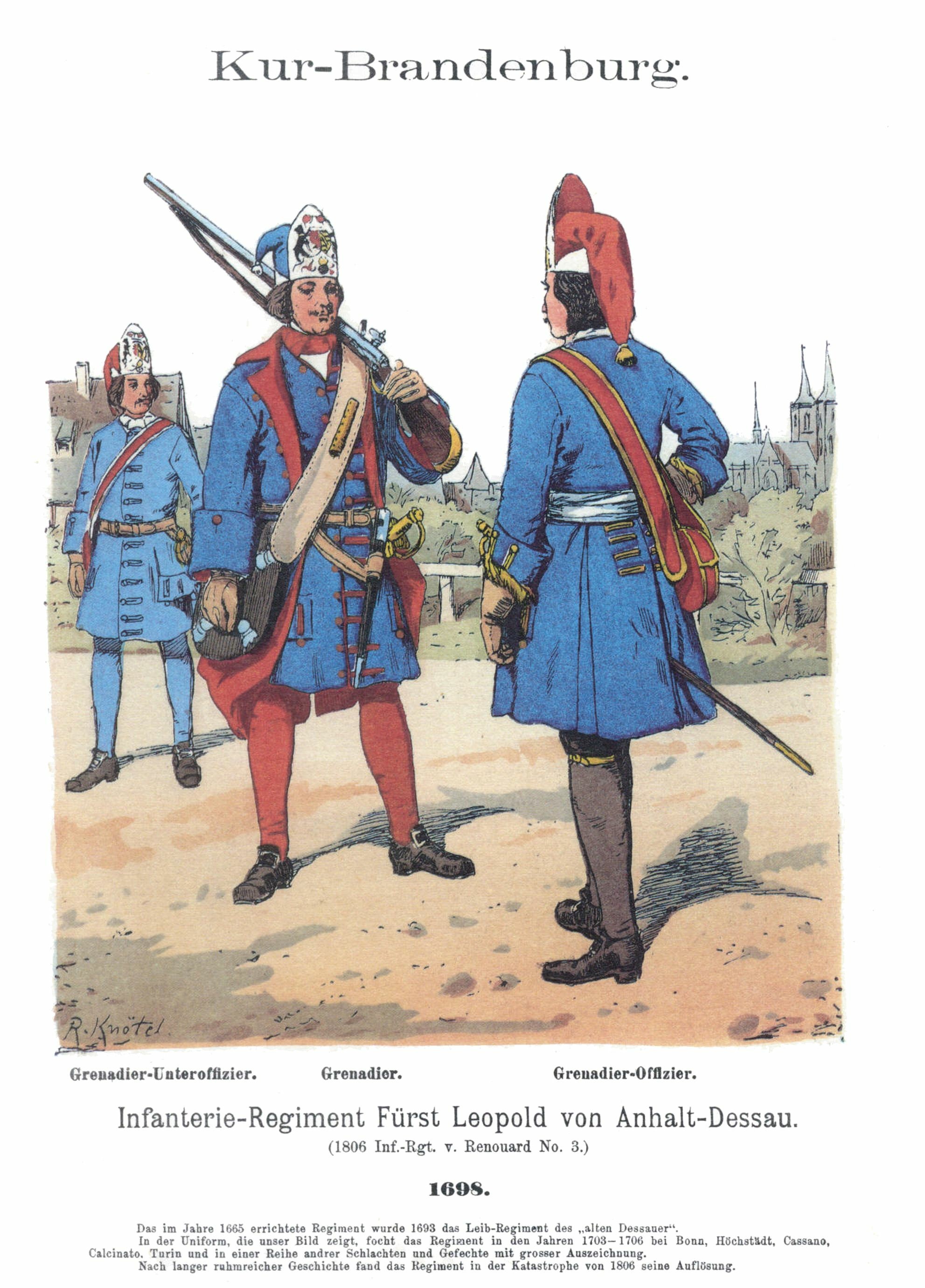

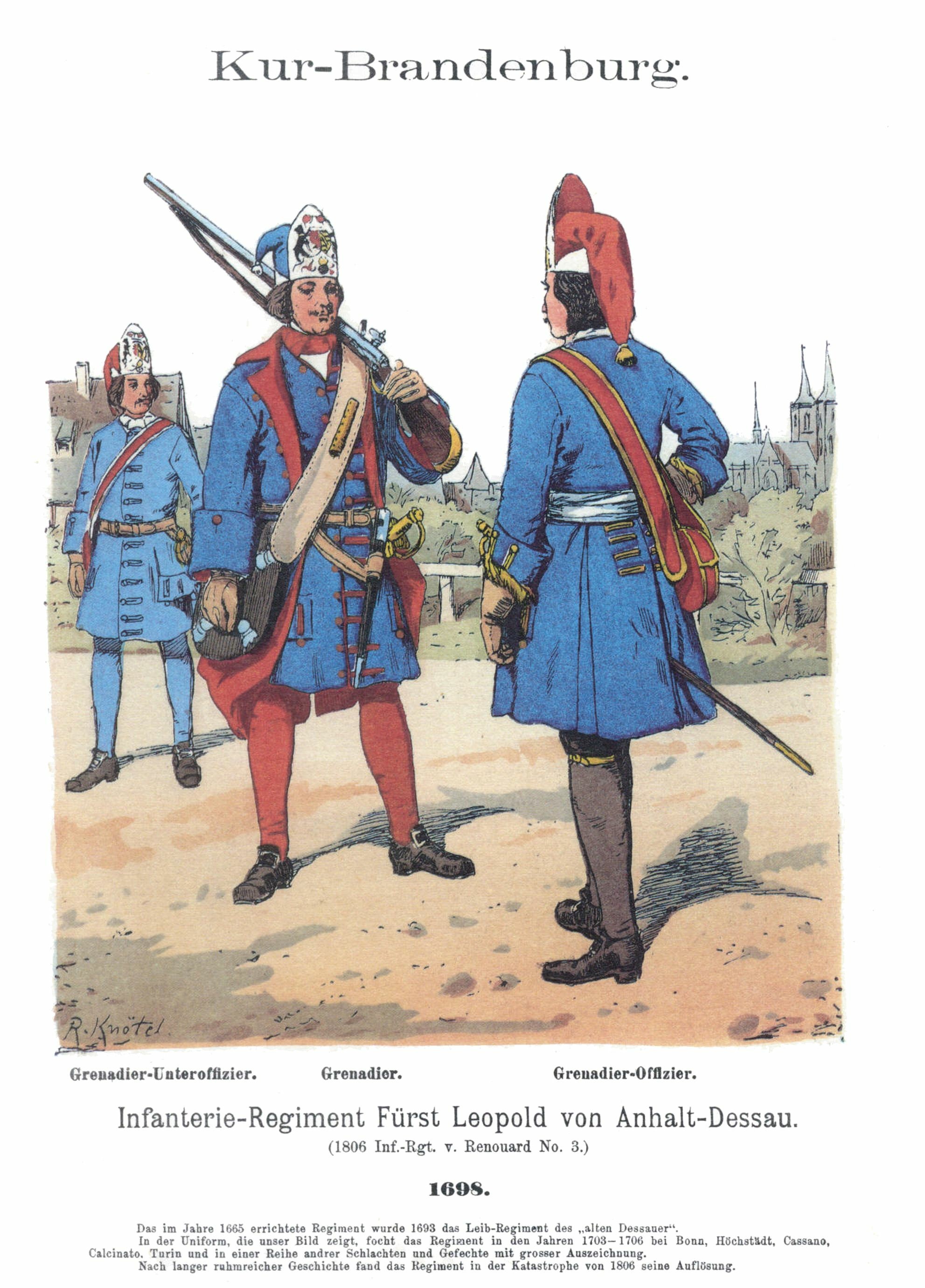

Frederick William I had begun his military innovations in his ''Kronprinz'' regiment during the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

. His friend, Leopold I, Prince of Anhalt-Dessau

Leopold I, Prince of Anhalt-Dessau (3 July 1676 – 7 April 1747) was a German prince of the House of Ascania and ruler of the principality of Anhalt-Dessau from 1693 to 1747. He was also a ''Generalfeldmarschall'' in the Prussian army. Nickname ...

, served as the royal drill sergeant for the Prussian Army. Leopold introduced the iron ramrod

A ramrod (or scouring stick) is a metal or wooden device used with muzzleloading firearms to push the projectile up against the propellant (mainly blackpowder). The ramrod was used with weapons such as muskets and cannons and was usually held i ...

, increasing Prussian firepower, and the slow march, or goose-step

The goose step is a special marching step which is performed during formal military parades and other ceremonies. While marching in parade formation, troops swing their legs in unison off the ground while keeping each leg rigidly straight.

The ...

. He also vastly increased the role of music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspect ...

in the Army, dedicating a large number of musician-troops, especially drummers and fifers, to use music for increasing morale

Morale, also known as esprit de corps (), is the capacity of a group's members to maintain belief in an institution or goal, particularly in the face of opposition or hardship. Morale is often referenced by authority figures as a generic value ...

in battle. The usefulness of music in battles was first recognized in the Thirty Years' War by the Brandenburger and Swedish armies. The new king trained and drilled the army relentlessly, focusing on their flintlock

Flintlock is a general term for any firearm that uses a flint-striking lock (firearm), ignition mechanism, the first of which appeared in Western Europe in the early 16th century. The term may also apply to a particular form of the mechanism its ...

muskets' firing speed and formation maneuverability. The changes gave the army flexibility, precision, and a rate of fire

Rate of fire is the frequency at which a specific weapon can fire or launch its projectiles. This can be influenced by several factors, including operator training level, mechanical limitations, ammunition availability, and weapon condition. In m ...

that was mostly unequalled for that period.Craig, p. 12. Through drilling and the iron ramrod, each soldier was expected to fire six times a minute, three times as fast as most armies.Reiners, p. 17.

Punishments were draconian

Draconian is an adjective meaning "of great severity", that derives from Draco, an Athenian law scribe under whom small offenses had heavy punishments ( Draconian laws).

Draconian may also refer to:

* Draconian (band), a death/doom metal band fro ...

in nature, such as running the gauntlet, and despite the threat of hanging, many peasant conscripts deserted when they could. Uniforms and weaponry were standardized. Pigtails and, in those regiments which wore it, facial hair were to be of uniform length within a regiment; soldiers who could not adequately grow beards or moustaches were expected to paint an outline on their faces.

Frederick William I reduced the size of Frederick I's gaudy royal guard

A royal guard is a group of military bodyguards, soldiers or armed retainers responsible for the protection of a royal person, such as the emperor or empress, king or queen, or prince or princess. They often are an elite unit of the regular arm ...

to a single regiment, a troop of taller-than-average soldiers known as the Potsdam Giants

The Potsdam Giants was the name given to Prussian infantry regiment No 6. The regiment was composed of taller-than-average soldiers, and was founded in 1675. It was eventually dissolved in 1806, after the Prussians were defeated by Napoleon. Throug ...

or more commonly the ''Lange Kerls'' (long fellows), which he privately funded.Koch, p. 79. The cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

was reorganized into 55 squadrons of 150 horses; the infantry was turned into 50 battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

s (25 regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscripted ...

s); and the artillery consisted of two battalions. These changes allowed him to increase the army from 39,000 to 45,000 troops; by the end of Frederick William I's reign, the army had doubled in size.Koch, p. 86. The General War Commissary, responsible for the army and revenue, was removed from interference by the estates and placed strictly under the control of officials appointed by the king.

Frederick William I restricted enrollment in the officer corps to Germans of noble descent and compelled the ''Junkers'', the Prussian landed aristocracy

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At t ...

, to serve in the army, Although initially reluctant about the army, the nobles eventually saw the officer corps as its natural profession. Until 1730 the common soldiers consisted largely of serfs

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed ...

recruited or impressed from Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a states of Germany, state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an ar ...

, Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

and East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

, leading many to flee to neighboring countries. In order to halt this trend, Frederick William I divided Prussia into regimental cantons. Every youth was required to serve as a soldier in these recruitment districts for three months each year; this met agrarian needs and added troops to bolster the regular ranks.

The General Directory which developed during Frederick William I's reign continued the absolutist tendencies of his grandfather and collected the increased taxes necessary for the expanded military. The middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Commo ...

of the towns was required to quarter soldiers and enroll in the bureaucracy. Because the excise tax

file:Lincoln Beer Stamp 1871.JPG, upright=1.2, 1871 U.S. Revenue stamp for 1/6 barrel of beer. Brewers would receive the stamp sheets, cut them into individual stamps, cancel them, and paste them over the Bunghole, bung of the beer barrel so when ...

was only applied in towns, the king was reluctant to engage in war, as deployment of his expensive army in foreign lands would have deprived him of taxes from the town-based military.

By the end of Frederick William I's reign, Prussia had the fourth-largest army (80,000 soldiers) in Europe but was twelfth in population size (2.5 million). This was maintained with a budget of five million thalers (out of a total state budget of seven million thalers).

Frederick the Great

Silesian Wars

hussar

A hussar ( , ; hu, huszár, pl, husarz, sh, husar / ) was a member of a class of light cavalry, originating in Central Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries. The title and distinctive dress of these horsemen were subsequently widely ...

s, and a squadron of life guards.

Disregarding the Pragmatic Sanction

A pragmatic sanction is a sovereign's solemn decree on a matter of primary importance and has the force of fundamental law. In the late history of the Holy Roman Empire, it referred more specifically to an edict issued by the Emperor.

When used ...

, Frederick began the Silesian Wars

The Silesian Wars (german: Schlesische Kriege, links=no) were three wars fought in the mid-18th century between Prussia (under King Frederick the Great) and Habsburg Austria (under Archduchess Maria Theresa) for control of the Central European ...

shortly after taking the throne. Although the inexperienced king retreated from the battle, the Prussian Army achieved victory over Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

in the Battle of Mollwitz

The Battle of Mollwitz was fought by Prussia and Austria on 10 April 1741, during the First Silesian War (in the early stages of the War of the Austrian Succession). It was the first battle of the new Prussian King Frederick II, in which both si ...

(1741) under the leadership of Field Marshal Schwerin

Schwerin (; Mecklenburgisch dialect, Mecklenburgian Low German: ''Swerin''; Latin: ''Suerina'', ''Suerinum'') is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Germany, second-largest city of the northeastern States of Germany, German ...

. The Prussian cavalry under Schulenburg

Schulenburg is a city in Fayette County, Texas, United States. The population was 2,633 at the 2020 census. Known for its German culture, Schulenburg is home of the Texas Polka Music Museum. It is in a rural, agricultural area settled by Germa ...

had performed poorly at Mollwitz; the cuirassier

Cuirassiers (; ) were cavalry equipped with a cuirass, sword, and pistols. Cuirassiers first appeared in mid-to-late 16th century Europe as a result of armoured cavalry, such as men-at-arms and demi-lancers, discarding their lances and adoptin ...

s, originally trained on heavy horses, were subsequently retrained on more maneuverable, lighter horses. The hussars and dragoon

Dragoons were originally a class of mounted infantry, who used horses for mobility, but dismounted to fight on foot. From the early 17th century onward, dragoons were increasingly also employed as conventional cavalry and trained for combat w ...

s of General Zieten were also expanded. These changes led to a Prussian victory at Chotusitz (1742) in Bohemia, and Austria conceded Silesia to Frederick with the Peace of Breslau.

In September 1743, Frederick held the first fall maneuver (''Herbstübung''). The different branches of the Army tested new formations and tactics; the fall maneuvers become annual traditions of the Prussian Army. Austria tried to reclaim Silesia in the Second Silesian War. Although successful in outmaneuvering Frederick in 1744, the Austrians were crushed by the king himself in the Battle of Hohenfriedberg

The Battle of Hohenfriedberg or Hohenfriedeberg, now Dobromierz, also known as the Battle of Striegau, now Strzegom, was one of Frederick the Great's most admired victories. Frederick's Prussian army decisively defeated an Austrian army unde ...

and the Battle of Soor

The Battle of Soor (30 September 1745) was a battle between Frederick the Great's Prussian army and an Austro-Saxon army led by Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine during the Second Silesian War (part of the War of the Austrian Succession). The ...

(1745). The Prussian cavalry excelled during the battle, especially the '' Zieten'' Hussars. For his great services at Hohenfriedberg Hans Karl von Winterfeldt

Hans Karl von Winterfeldt (4 April 1707 – 8 September 1757), a Prussian general, served in the War of the Polish Succession, the War of Austrian Succession, Frederick the Great's Silesian wars and the Seven Years' War. One of Frederick's ...

, a good friend of King Frederick, rose to prominence.

Third Silesian War

Austria allied with its traditional rival, France, in theDiplomatic Revolution

The Diplomatic Revolution of 1756 was the reversal of longstanding alliances in Europe between the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years' War. Austria went from an ally of Britain to an ally of France, the Dutch Republic, a long stan ...

(1756); Austria, France, and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

were all aligned against Prussia. Frederick preemptively attacked his enemies with an army of 150,000, beginning the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

. The Austrian Army had been reformed by Kaunitz

Wenzel Anton, Prince of Kaunitz-Rietberg (german: Wenzel Anton Reichsfürst von Kaunitz-Rietberg, cz, Václav Antonín z Kounic a Rietbergu; 2 February 1711 – 27 June 1794) was an Austrian and Czech diplomat and statesman in the Habsburg monarc ...

, and the improvements showed in their success over Prussia at Kolin. Frederick achieved one of his greatest victories, however, at Rossbach, where the Prussian cavalry of Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz

Friedrich Wilhelm Freiherr von Seydlitz (3 February 1721 – 8 November 1773) was a Prussian officer, lieutenant general, and among the greatest of the Prussian cavalry generals. He commanded one of the first Hussar squadrons ...

smashed a larger Franco-Imperial army with minimal casualties, despite being outnumbered two to one. Frederick then rushed eastward to Silesia, where Austria had defeated the Prussian army under the Duke of Bevern. After a series of complicated formations and deployments hidden from the Austrians, the Prussians successfully struck their enemy's flank at Leuthen, with Friedrich once again directing the battle; the Austrian position in the province collapsed, resulting in a Prussian victory even more impressive than the one at Rossbach.

Frederick's maneuvers were unsuccessful against the Russians in the bloody

Frederick's maneuvers were unsuccessful against the Russians in the bloody Battle of Zorndorf

The Battle of Zorndorf, during the Seven Years' War, was fought on 25 August 1758 between Russian troops commanded by Count William Fermor and a Prussian army commanded by King Frederick the Great. The battle was tactically inconclusive, with b ...

, however, and Prussian forces were crushed at Kunersdorf (1759). Like the results after the Battle of Hochkirch

The Battle of Hochkirch took place on 14 October 1758, during the Third Silesian War (part of the Seven Years' War). After several weeks of maneuvering for position, an Austrian army of 80,000 commanded by Lieutenant Field Marshal Leopold Josef ...

, though, in which the Prussians had to withdraw, the Austrian and Russian Allies did not follow up on their victory. Within the week, the Russian force began a withdrawal eastward; Austrians retreated southward.

Prussia was ill-suited for lengthy wars, and a Prussian collapse seemed imminent on account of casualties and lack of resources, but after two more years of campaigning, Frederick was saved by the "Miracle of the House of Brandenburg

The Miracle of the House of Brandenburg is the name given by Frederick II of Prussia to the failure of Russia and Austria to follow up their victory over him at the Battle of Kunersdorf on 12 August 1759 during the Seven Years' War. The name is s ...

" — the Russian exit from the war after the sudden death of Empress Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

in 1762. Prussian control of Silesia was confirmed in the Treaty of Hubertusburg

The Treaty of Hubertusburg (german: Frieden von Hubertusburg) was signed on 15 February 1763 at Hubertusburg Castle by Prussia, Austria and Saxony to end the Third Silesian War. Together with the Treaty of Paris, signed five days earlier, it marke ...

(1763). Severe casualties had led the king to admit middle class officers during the war, but this trend was reversed afterwards.Craig, p. 17.

The offensive-minded Frederick advocated the oblique order

The oblique order (also known as the 'declined flank') is a military tactic whereby an attacking army focuses its forces to attack a single enemy flank. The force commander concentrates the majority of their strength on one flank and uses the re ...

of battle, which required considerable discipline and mobility. This tactic failed at Kunersdorf primarily because of the terrain, which could not be used to an advantage. The Russians had arrived early and fortified themselves on the high ground. Frederick used oblique order to great success at Hohenfriedberg and later Leuthen. After a few initial volley fire

Volley fire, as a military tactic, is (in its simplest form) the concept of having soldiers shoot in the same direction en masse. In practice, it often consists of having a line of soldiers all discharge their weapons simultaneously at the enemy ...

, the infantry was to advance quickly for a bayonet

A bayonet (from French ) is a knife, dagger, sword, or spike-shaped weapon designed to fit on the end of the muzzle of a rifle, musket or similar firearm, allowing it to be used as a spear-like weapon.Brayley, Martin, ''Bayonets: An Illustr ...

charge. The Prussian cavalry was to attack as a large formation with swords before the opposing cavalry could attack.

An army with a country

The first

The first garrison

A garrison (from the French ''garnison'', itself from the verb ''garnir'', "to equip") is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a mil ...

began construction in Berlin in 1764. While Frederick William I wanted to have a mostly native-born army, Frederick II wanted to have a mostly foreign-born army, preferring to have native Prussians be taxpayers and producers. The Prussian Army consisted of 187,000 soldiers in 1776, 90,000 of whom were Prussian subjects in central and eastern Prussia. The remainder were foreign (both German and non-German) volunteers or conscripts. Frederick established the ''Gardes du Corps'' as the royal guard. Many troops were disloyal, such as mercenaries or those acquired through impressment, while troops recruited from the canton system displayed strong regional, and nascent national pride. During the Seven Years' War, the elite regiments of the army were almost entirely composed of native Prussians. By the end of Frederick's reign, the army had become an integral part of Prussian society. It numbered 200,000 soldiers, making it the third-largest in Europe after the armies of Russia and Austria. The social classes were all expected to serve the state and its military — the nobility led the army, the middle class supplied the army, and the peasants composed the army. Minister Friedrich von Schrötter remarked that, "Prussia was not a country with an army, but an army with a country".

The Napoleonic Wars

Defeat

Frederick the Great's successor, his nephew Frederick William II (1786–97), relaxed conditions in Prussia and had little interest in war. He delegated responsibility to the agedCharles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick

Charles William Ferdinand (german: Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand; 9 October 1735 – 10 November 1806) was the Prince of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel and Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and a military leader. His titles are usually shortened to Duke of Brunswi ...

, and the army began to degrade in quality. Led by veterans of the Silesian Wars, the Prussian Army was ill-equipped to deal with Revolutionary France

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

. The officers retained the same training, tactics and weaponry used by Frederick the Great some forty years earlier. In comparison, the revolutionary army of France, especially under Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

, was developing new methods of organization, supply, mobility, and command.

Prussia withdrew from the First Coalition

The War of the First Coalition (french: Guerre de la Première Coalition) was a set of wars that several European powers fought between 1792 and 1797 initially against the constitutional Kingdom of France and then the French Republic that suc ...

in the Peace of Basel

The Peace of Basel of 1795 consists of three peace treaties involving France during the French Revolution (represented by François de Barthélemy).

*The first was with Prussia (represented by Karl August von Hardenberg) on 5 April;

*The seco ...

(1795), ceding the Rhenish territories to France. Upon Frederick William II's death in 1797, the state was bankrupt and the army outdated. He was succeeded by his son, Frederick William III

Frederick William III (german: Friedrich Wilhelm III.; 3 August 1770 – 7 June 1840) was King of Prussia from 16 November 1797 until his death in 1840. He was concurrently Elector of Brandenburg in the Holy Roman Empire until 6 August 1806, wh ...

(1797–1840), who involved Prussia in the disastrous Fourth Coalition

The Fourth Coalition fought against Napoleon's French Empire and were defeated in a war spanning 1806–1807. The main coalition partners were Prussia and Russia with Saxony, Sweden, and Great Britain also contributing. Excluding Prussia, ...

. The Prussian Army was decisively defeated in the battles of Saalfeld

Saalfeld (german: Saalfeld/Saale) is a town in Germany, capital of the Saalfeld-Rudolstadt district of Thuringia. It is best known internationally as the ancestral seat of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Saxe-Coburg and Gotha branch of the S ...

, Jena and Auerstedt in 1806 and Napoleon occupied Berlin. The Prussians' famed discipline collapsed and led to widescale surrendering among infantry, cavalry and garrisons. While some Prussian commanders acquitted themselves well, such as L'Estocq

The L'Estocq family is a German noble family of French-Huguenot origin. Members of the family held significant military positions in the Kingdom of Prussia and Russia.

Notable members

*Jean Armand de L'Estocq (1692–1767), French adventurer

* ...

at Eylau, Gneisenau at Kolberg, and Blücher at Lübeck

Lübeck (; Low German also ), officially the Hanseatic City of Lübeck (german: Hansestadt Lübeck), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 217,000 inhabitants, Lübeck is the second-largest city on the German Baltic coast and in the stat ...

, they were not enough to reverse the defeats of Jena-Auerstedt. Prussia submitted to major territorial losses, a standing army of only 42,000 men, and an alliance with France in the Treaty of Tilsit

The Treaties of Tilsit were two agreements signed by French Emperor Napoleon in the town of Tilsit in July 1807 in the aftermath of his victory at Friedland. The first was signed on 7 July, between Napoleon and Russian Emperor Alexander, when t ...

(1807).

Reform

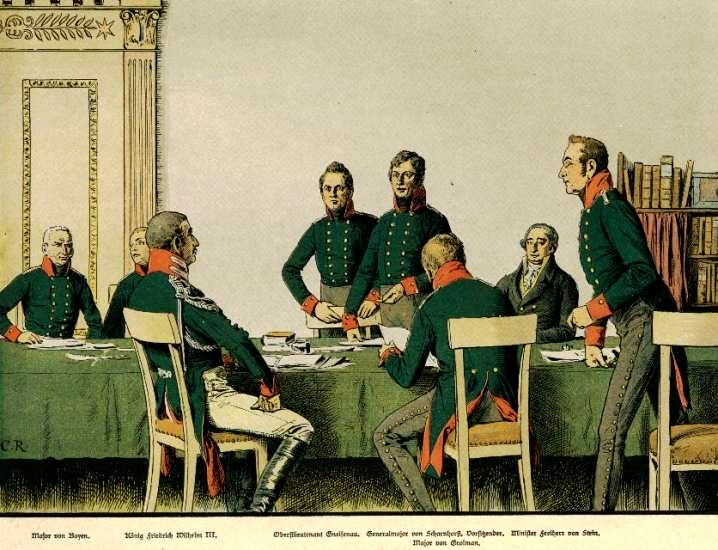

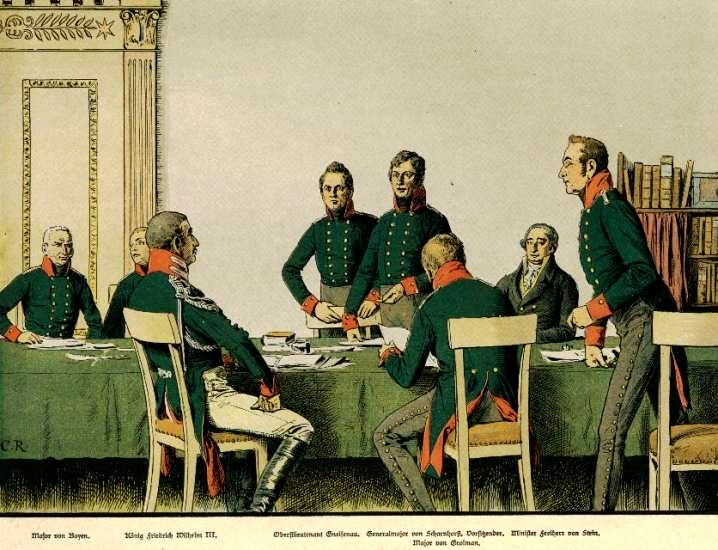

The defeat of the disorganized army shocked the Prussian establishment, which had largely felt invincible after the Frederician victories. While Baron vom Stein and Prime Minister

The defeat of the disorganized army shocked the Prussian establishment, which had largely felt invincible after the Frederician victories. While Baron vom Stein and Prime Minister Karl August von Hardenberg

Karl August Fürst von Hardenberg (31 May 1750, in Essenrode-Lehre – 26 November 1822, in Genoa) was a Prussian statesman and Prime Minister of Prussia. While during his late career he acquiesced to reactionary policies, earlier in his career ...

began modernizing the Prussian state, General Gerhard von Scharnhorst

Gerhard Johann David von Scharnhorst (12 November 1755 – 28 June 1813) was a Hanoverian-born general in Prussian service from 1801. As the first Chief of the Prussian General Staff, he was noted for his military theories, his reforms of the Pru ...

began to reform the military. He led a Military Reorganization Committee, which included Generals August von Gneisenau

August Wilhelm Antonius Graf Neidhardt von Gneisenau (27 October 176023 August 1831) was a Prussian field marshal. He was a prominent figure in the reform of the Prussian military and the War of Liberation.

Early life

Gneisenau was born at Schil ...

, Karl von Grolman

Karl Wilhelm Georg von Grolman(n) (30 July 1777 – 1 June 1843) was a Prussian general who fought in the Napoleonic Wars.

Biography

Grolman was born in Berlin. He entered an infantry regiment at the age of thirteen years, was commissioned as an ...

, and Hermann von Boyen

Leopold Hermann Ludwig von Boyen (20 June 1771 – 15 February 1848) was a Prussian army officer who helped to reform the Prussian Army in the early 19th century. He also served as minister of war of Prussia in the period 1810-1813 and later aga ...

as well as the civilian vom Steinen.Citino, p. 128. Prussian military officer, Carl von Clausewitz

Carl Philipp Gottfried (or Gottlieb) von Clausewitz (; 1 June 1780 – 16 November 1831) was a Prussian general and military theorist who stressed the "moral", in modern terms meaning psychological, and political aspects of waging war. His mos ...

assisted with the reorganization as well. Dismayed by the populace's indifferent reaction to the 1806 defeats, the reformers wanted to cultivate patriotism

Patriotism is the feeling of love, devotion, and sense of attachment to one's country. This attachment can be a combination of many different feelings, language relating to one's own homeland, including ethnic, cultural, political or histor ...

within the country. Stein's reforms abolished serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

in 1807 and initiated local city government in 1808.

The generals of the army were completely overhauled — of the 143 Prussian generals in 1806, only Blücher and Tauentzien remained by the

The generals of the army were completely overhauled — of the 143 Prussian generals in 1806, only Blücher and Tauentzien remained by the Sixth Coalition

Sixth is the ordinal form of the number six.

* The Sixth Amendment, to the U.S. Constitution

* A keg of beer, equal to 5 U.S. gallons or barrel

* The fraction

Music

* Sixth interval (music)s:

** major sixth, a musical interval

** minor sixth ...

;Koch, p. 183. many were allowed to redeem their reputations in the war of 1813. The officer corps was reopened to the middle class in 1808, while advancement into the higher ranks became based on education. King Frederick William III created the War Ministry in 1809, and Scharnhorst founded an officers training school, the later Prussian War Academy

The Prussian Staff College, also Prussian War College (german: Preußische Kriegsakademie) was the highest military facility of the Kingdom of Prussia to educate, train, and develop general staff officers.

Location

It originated with the ''Ak ...

, in Berlin in 1810.

Scharnhorst advocated adopting the ''levée en masse

''Levée en masse'' ( or, in English, "mass levy") is a French term used for a policy of mass national conscription, often in the face of invasion.

The concept originated during the French Revolutionary Wars, particularly for the period followi ...

'', the universal military conscription used by France. He created the ''Krümpersystem'', by which companies replaced 3–5 men monthly, allowing up to 60 extra men to be trained annually per company. This system granted the army a larger reserve of 30,000–150,000 extra troops. The ''Krümpersystem'' was also the beginning of short-term (3 years') compulsory service in Prussia, as opposed to the long-term (5 to 10 years') conscription previously used since the 1650s. Because the occupying French prohibited the Prussians from forming divisions, the Prussian Army was divided into six brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute a division.

Br ...

s, each consisting of seven to eight infantry battalions and twelve squadrons of cavalry. The combined brigades were supplemented with three brigades of artillery.

Corporal punishment was by and large abolished, while soldiers were trained in the field and in ''tirailleur

A tirailleur (), in the Napoleonic era, was a type of light infantry trained to skirmish ahead of the main columns. Later, the term "''tirailleur''" was used by the French Army as a designation for indigenous infantry recruited in the French c ...

'' tactics. Scharnhorst promoted the integration of the infantry, cavalry, artillery, and engineers (sappers) through combined arms

Combined arms is an approach to warfare

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme vio ...

, as opposed to their previous independent states. Equipment and tactics were updated in respect to the Napoleonic campaigns. The field manual issued by Yorck

''Yorck'' is a 1931 German war film directed by Gustav Ucicky and starring Werner Krauss, Grete Mosheim and Rudolf Forster.Noack p.59 It portrays the life of the Prussian General Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg, particularly his refusal to serve i ...

in 1812 emphasized combined arms and faster marching speeds. In 1813, Scharnhorst succeeded in attaching a chief of staff trained at the academy to each field commander.

Some reforms were opposed by Frederician traditionalists, such as Yorck, who felt that middle class officers would erode the privileges of the aristocratic officer corps and promote the ideas of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

. The army reform movement was cut short by Scharnhorst's death in 1813. The shift to a more democratic and middle-class military began to lose momentum in the face of the reactionary government.

Wars of the Sixth And Seventh Coalition

The reformers and much of the public called for Frederick William III to ally with the

The reformers and much of the public called for Frederick William III to ally with the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

in its 1809 campaign against France. When the cautious king refused to support a new Prussian war, however, Schill led his hussar regiment against the occupying French, expecting to provoke a national uprising. The king considered Schill a mutineer, and the major's rebellion was crushed at Stralsund

Stralsund (; Swedish: ''Strålsund''), officially the Hanseatic City of Stralsund (German: ''Hansestadt Stralsund''), is the fifth-largest city in the northeastern German federal state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rostock, Schwerin, Neub ...

by French allies. The Franco-Prussian treaty of 1812 forced Prussia to provide 20,000 troops to Napoleon's ''Grande Armée

''La Grande Armée'' (; ) was the main military component of the French Imperial Army commanded by Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte during the Napoleonic Wars. From 1804 to 1808, it won a series of military victories that allowed the French Empi ...

'', first under the leadership of Grawert and then under Yorck. The French occupation of Prussia was reaffirmed, and 300 demoralized Prussian officers resigned in protest.

During Napoleon's retreat from Russia in 1812, Yorck independently signed the Convention of Tauroggen

The Convention of Tauroggen was an armistice signed 30 December 1812 at Tauroggen (now Tauragė, Lithuania) between General Ludwig Yorck on behalf of his Prussian troops and General Hans Karl von Diebitsch of the Imperial Russian Army. Yorck's a ...

with Russia, breaking the Franco-Prussian alliance. Stein arrived in East Prussia and led the raising of a ''Landwehr

''Landwehr'', or ''Landeswehr'', is a German language term used in referring to certain national army, armies, or militias found in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Europe. In different context it refers to large-scale, low-strength fortif ...

'', or militia to defend the province. With Prussia's joining of the Sixth Coalition

Sixth is the ordinal form of the number six.

* The Sixth Amendment, to the U.S. Constitution

* A keg of beer, equal to 5 U.S. gallons or barrel

* The fraction

Music

* Sixth interval (music)s:

** major sixth, a musical interval

** minor sixth ...

out of his hands, Frederick William III quickly began to mobilize the army, and the East Prussian ''Landwehr'' was duplicated in the rest of the country. In comparison to 1806, the Prussian populace, especially the middle class, was supportive of the war, and thousands of volunteers joined the army. Prussian troops under the leadership of Blücher and Gneisenau proved vital at the Battles of Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as wel ...

(1813) and Waterloo

Waterloo most commonly refers to:

* Battle of Waterloo, a battle on 18 June 1815 in which Napoleon met his final defeat

* Waterloo, Belgium, where the battle took place.

Waterloo may also refer to:

Other places

Antarctica

*King George Island (S ...

(1815). Later staff officers were impressed with the simultaneous operations of separate groups of the Prussian Army.

The Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia est ...

was introduced as a military decoration

Military awards and decorations are distinctions given as a mark of honor for military heroism, meritorious or outstanding service or achievement. DoD Manual 1348.33, 2010, Vol. 3 A decoration is often a medal consisting of a ribbon and a medal ...

by King Frederick William III in 1813. After the publication of his book ''On War

''Vom Kriege'' () is a book on war and military strategy by Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz (1780–1831), written mostly after the Napoleonic wars, between 1816 and 1830, and published posthumously by his wife Marie von Brühl in 1832. I ...

'', Clausewitz became a widely studied philosopher of war.

19th century

Bulwark of conservatism

The

The Prussian General Staff

The German General Staff, originally the Prussian General Staff and officially the Great General Staff (german: Großer Generalstab), was a full-time body at the head of the Prussian Army and later, the German Army, responsible for the continuou ...

, which developed out of meetings of the Great Elector with his senior officers and the informal meeting of the Napoleonic Era reformers, was formally created in 1814. In the same year Boyen and Grolman drafted a law for universal conscription, by which men would successively serve in the standing army, the ''Landwehr'' and the local ''Landsturm

In German-speaking countries, the term ''Landsturm'' was historically used to refer to militia or military units composed of troops of inferior quality. It is particularly associated with Prussia, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Sweden and the Nether ...

'' until the age of 39. Troops of the 156,000-strong standing army served for three years and were in the reserves for two, while militiamen of the 163,000-strong ''Landwehr'' served a few weeks annually for seven years. Boyen and Blücher strongly supported the civilian army of the ''Landwehr'', which was to unite military and civilian society, as an equal to the standing army.

During a constitutional crisis in 1819, Frederick William III recognized Prussia's adherence to the anti-revolutionary Carlsbad Decrees

The Carlsbad Decrees (german: Karlsbader Beschlüsse) were a set of reactionary restrictions introduced in the states of the German Confederation by resolution of the Bundesversammlung on 20 September 1819 after a conference held in the spa town ...

. Conservative forces within Prussia, such as Wittgenstein

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein ( ; ; 26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austrians, Austrian-British people, British philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy o ...

, remained opposed to conscription and the more democratic ''Landwehr''. Frederick William III reduced the militia's size and placed it under the control of the regular army in 1819, leading to the resignations of Boyen and Grolman and the ending of the reform movement. Boyen's ideal of an enlightened citizen soldier was replaced with the idea of a professional military separate or alienated from civilian society.

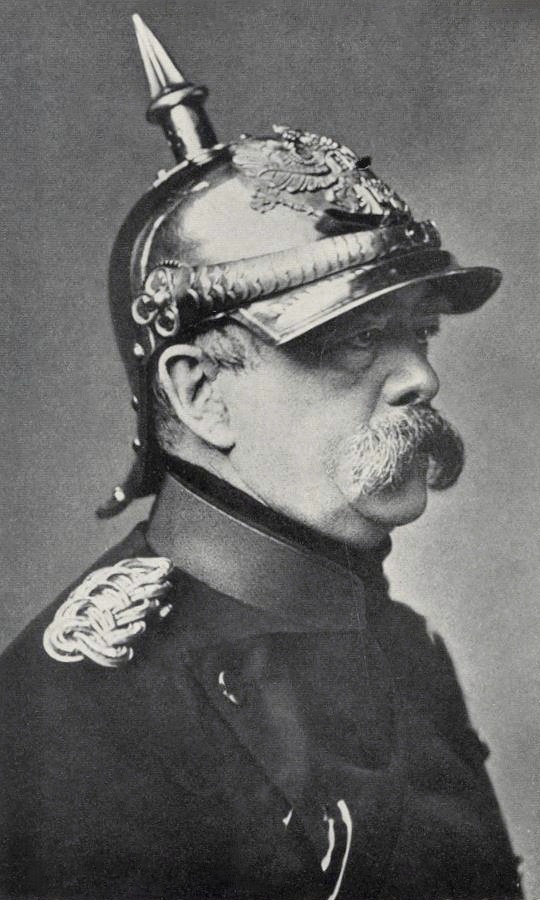

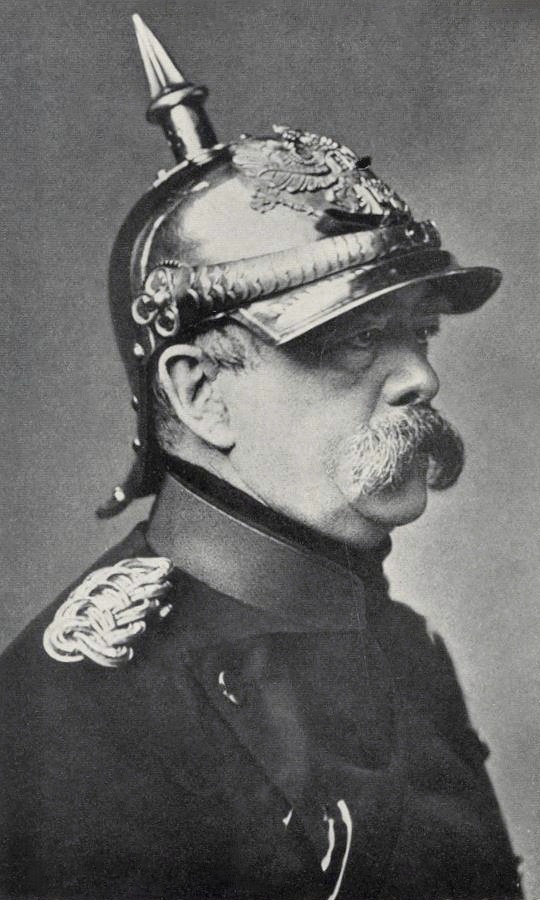

By the middle of the 19th century, Prussia was seen by many German liberals as the country best-suited to unify the many German states, but the conservative government used the army to repress liberal and democratic tendencies during the 1830s and 1840s. Liberals resented the usage of the army in essentially police actions. King

By the middle of the 19th century, Prussia was seen by many German liberals as the country best-suited to unify the many German states, but the conservative government used the army to repress liberal and democratic tendencies during the 1830s and 1840s. Liberals resented the usage of the army in essentially police actions. King Frederick William IV

Frederick William IV (german: Friedrich Wilhelm IV.; 15 October 17952 January 1861), the eldest son and successor of Frederick William III of Prussia, reigned as King of Prussia from 7 June 1840 to his death on 2 January 1861. Also referred to ...

(1840–61) initially appeared to be a liberal ruler, but he was opposed to issuing the written constitution called for by reformers. When barricades were raised in Berlin during the 1848 revolution

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

, the king reluctantly agreed to the creation of a civilian defense force (''Bürgerwehr'') in his capital. A national assembly to write a constitution was convened for the first time, but its slowness allowed the reactionary forces to regroup. General Friedrich Graf von Wrangel

Friedrich Heinrich Ernst Graf von Wrangel (13 April 1784 – 2 November 1877) was a ''Generalfeldmarschall'' of the Prussian Army.

A Baltic German, he was nicknamed "Papa Wrangel" and was a member of the Baltic noble family of Wrangel.

Ea ...

led the reconquest of Berlin, which was supported by a middle class weary of a people's revolution. Prussian troops were subsequently used to suppress the revolution in many other German cities.

At the end of 1848, Frederick William finally issued the Constitution of the Kingdom of Prussia. The liberal opposition secured the creation of a parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

, but the constitution was largely a conservative document reaffirming the monarchy's predominance. The army was a praetorian guard

The Praetorian Guard (Latin: ''cohortēs praetōriae'') was a unit of the Imperial Roman army that served as personal bodyguards and intelligence agents for the Roman emperors. During the Roman Republic, the Praetorian Guard were an escort fo ...

outside of the constitution, subject only to the king. The Prussian Minister of War was the only soldier required to swear an oath defending the constitution, leading ministers such as Strotha, Bonin and Waldersee Waldersee is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Alfred von Waldersee (1832–1904), German field marshal

* Friedrich Graf von Waldersee (1795–1864), German Prussian Lieutenant General and military author

* Georg von Waldersee ( ...

to be criticized by either the king or the parliament, depending on their political views. The army's budget had to be approved by the Lower House of Parliament. Novels and memoirs glorifying the army, especially its involvement in the Napoleonic Wars, began to be published to sway public opinion. The defeat at Olmütz

Olomouc (, , ; german: Olmütz; pl, Ołomuniec ; la, Olomucium or ''Iuliomontium'') is a city in the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, i ...

of the liberals' plan to unite Germany through Prussia encouraged reactionary forces. In 1856 during peacetime Prussian Army consisted of 86,436 infantrymen, 152 cavalry squadrons and 9 artillery regiments.

After Frederick William IV suffered a stroke, his brother William I

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 1087 ...

became regent (1857) and king (1861–88). He desired to reform the army, which conservatives such as Roon considered to have degraded since 1820 because of liberalism. The king wanted to expand the army—while the populace had risen from 10 million to 18 million since 1820, the annual army recruits had remained 40,000. Although Bonin opposed Roon's desired weakening of the ''Landwehr'', William I was alarmed by the nationalistic Second Italian War of Independence

The Second Italian War of Independence, also called the Franco-Austrian War, the Austro-Sardinian War or Italian War of 1859 ( it, Seconda guerra d'indipendenza italiana; french: Campagne d'Italie), was fought by the Second French Empire and t ...

. Bonin resigned as Minister of War and was replaced with Roon.

The government submitted Roon's army reform bill in February 1860. Parliament opposed many of its provisions, especially the weakening of the ''Landwehr'', and proposed a revised bill that did away with many of the government's desired reforms. The Finance Minister, Patow, abruptly withdrew the bill on 5 May and instead simply requested a provisional budgetary increase of 9 million thalers, which was granted. William had already begun creating 'combined regiments' to replace the ''Landwehr'', a process which increased after Patow acquired the additional funds. Although parliament was opposed to these actions, William maintained the new regiments with the guidance of