Armed Forces Special Weapons Project on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Armed Forces Special Weapons Project (AFSWP) was a United States military agency responsible for those aspects of

File:Leslie_Groves.jpg, alt=Head and shoulders of a man in uniform, Major General Leslie R. Groves Jr. (1947–1948)

File:Kenneth D. Nichols.jpeg, alt=Head and shoulders of a man in uniform with a peaked cap, Major General Kenneth D. Nichols (1948–1951)

File:Herbert Loper.jpeg, alt=Head and shoulders of a man in uniform, Major General Herbert B. Loper (1952–1953)

File:Alvin Luedecke.jpeg, alt=Head and shoulders of a man in uniform, Major General Alvin R. Luedecke (1953–1957)

File:Edward Parker.jpeg, alt=Head and shoulders of a man in uniform, Rear Admiral Edward N. Parker (1957–1959)

Patterson asked Groves to create a new agency to take over responsibility for the aspects of nuclear weapons that still remained under the military. It was to be jointly staffed by the Army and Navy, and on 29 January 1947, Patterson and Forrestal issued a memorandum that formally established the AFSWP. Its chief would be appointed jointly by the Chief of Staff of the Army and the Chief of Naval Operations, along with a deputy from the opposite service. Both would be members of the Military Liaison Committee, because the Atomic Energy Act stipulated that the Military Liaison Committee was the sole military body that dealt with the AEC. In February 1947, Eisenhower and Chief of Naval Operations Fleet Admiral  The 2761st Engineer Battalion (Special) at Sandia was commanded by

The 2761st Engineer Battalion (Special) at Sandia was commanded by

The 1947 nuclear stockpile consisted of nuclear weapons components, not weapons. Meeting with Truman in April 1947, Lilienthal informed him that not only were there no assembled weapons, there were only a few sets of components and no fully trained bomb-assembly teams. By August 1946, Sandia Base held electrical and mechanical assemblies for about 50 Fat Man bombs, but there were only nine fissile cores in storage. The stockpile of cores grew to 13 in 1947, and 53 in 1948. Oppenheimer noted that the bombs were "still largely the haywire contraptions that were slapped together in 1945". With a half-life of only 140 days, the polonium-beryllium modulated neutron initiators had to be periodically removed from the plutonium pits, tested, and, if necessary, replaced. The cores had to be stored separately from the high-explosive blocks that would surround them in the bomb because they generated enough heat to melt the plastic explosive over time. The heat could also affect the cores themselves, provoking a

The 1947 nuclear stockpile consisted of nuclear weapons components, not weapons. Meeting with Truman in April 1947, Lilienthal informed him that not only were there no assembled weapons, there were only a few sets of components and no fully trained bomb-assembly teams. By August 1946, Sandia Base held electrical and mechanical assemblies for about 50 Fat Man bombs, but there were only nine fissile cores in storage. The stockpile of cores grew to 13 in 1947, and 53 in 1948. Oppenheimer noted that the bombs were "still largely the haywire contraptions that were slapped together in 1945". With a half-life of only 140 days, the polonium-beryllium modulated neutron initiators had to be periodically removed from the plutonium pits, tested, and, if necessary, replaced. The cores had to be stored separately from the high-explosive blocks that would surround them in the bomb because they generated enough heat to melt the plastic explosive over time. The heat could also affect the cores themselves, provoking a  The 38th Engineer Battalion's electrical group studied the batteries, the electrical firing systems and the radar fuzes which detonated the bomb at the required altitude. The mechanical group dealt with the exploding-bridgewire detonators and the explosive lenses. The nuclear group moved to Los Alamos to study the cores and initiators. As part of their training, they attended lectures by Edward Teller, Hans Bethe,

The 38th Engineer Battalion's electrical group studied the batteries, the electrical firing systems and the radar fuzes which detonated the bomb at the required altitude. The mechanical group dealt with the exploding-bridgewire detonators and the explosive lenses. The nuclear group moved to Los Alamos to study the cores and initiators. As part of their training, they attended lectures by Edward Teller, Hans Bethe,

In addition to assembly of weapons, the AFSWP supported nuclear weapons testing. For Operation Sandstone in 1948, Groves ordered Dorland to fill every possible job with his men. He did this so well that Strauss, now an AEC commissioner, became disturbed at the number of AFSWP personnel who were participating, and feared that the

In addition to assembly of weapons, the AFSWP supported nuclear weapons testing. For Operation Sandstone in 1948, Groves ordered Dorland to fill every possible job with his men. He did this so well that Strauss, now an AEC commissioner, became disturbed at the number of AFSWP personnel who were participating, and feared that the

Groves retired at the end of February 1948, and Nichols was designated as his successor with the rank of major general. At the same time, Forrestal, now the Secretary of Defense, reorganized the Military Liaison Committee. A civilian, Donald F. Carpenter, replaced Brereton as chairman, and there were now two members from each of the three services. On 11 March, Truman summoned Lilienthal, Nichols and Secretary of the Army

Groves retired at the end of February 1948, and Nichols was designated as his successor with the rank of major general. At the same time, Forrestal, now the Secretary of Defense, reorganized the Military Liaison Committee. A civilian, Donald F. Carpenter, replaced Brereton as chairman, and there were now two members from each of the three services. On 11 March, Truman summoned Lilienthal, Nichols and Secretary of the Army

nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

s remaining under military control after the Manhattan Project was succeeded by the Atomic Energy Commission on 1 January 1947. These responsibilities included the maintenance, storage, surveillance, security and handling of nuclear weapons, as well as supporting nuclear testing. The AFSWP was a joint organization, staffed by the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

, United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

and United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army S ...

; its chief was supported by deputies from the other two services. Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Leslie R. Groves

Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves Jr. (17 August 1896 – 13 July 1970) was a United States Army Corps of Engineers officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and directed the Manhattan Project, a top secret research project ...

, the former head of the Manhattan Project, was its first chief.

The early nuclear weapons were large, complex, and cumbersome. They were stored as components rather than complete devices and required expert knowledge to assemble. The short life of their lead-acid batteries and modulated neutron initiators, and the heat generated by the fissile cores, precluded storing them assembled. The large quantity of conventional explosive in each weapon demanded special care be taken in handling. Groves hand-picked a team of regular Army officers, who were trained in the assembly and handling of the weapons. They in turn trained the enlisted soldiers, and the Army teams then trained teams from the Navy and Air Force.

As nuclear weapons development proceeded, the weapons became mass-produced, smaller, lighter, and easier to store, handle, and maintain. They also required less effort to assemble. The AFSWP gradually shifted its emphasis away from training assembly teams, and became more involved in stockpile management and providing administrative, technical, and logistical support. It supported nuclear weapons testing, although after Operation Sandstone in 1948, this was increasingly in a planning and training capacity rather than a field role. In 1959, the AFSWP became the Defense Atomic Support Agency (DASA), a field agency of the Department of Defense.

Origins

Nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

s were developed during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

by the Manhattan Project, a major research and development effort led by the United States, with participation from the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, it was under the direction of Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Leslie R. Groves Jr., of the US Army Corps of Engineers

, colors =

, anniversaries = 16 June (Organization Day)

, battles =

, battles_label = Wars

, website =

, commander1 = ...

. It created a network of production facilities, most notably for uranium enrichment at Oak Ridge, Tennessee

Oak Ridge is a city in Anderson and Roane counties in the eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about west of downtown Knoxville. Oak Ridge's population was 31,402 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Knoxville Metropolitan Area. O ...

, plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhib ...

production at Hanford, Washington, and weapons research and design at the Los Alamos Laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico. The nuclear weapons that were developed were used in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

in August 1945.

After the war ended, the Manhattan Project supported the nuclear weapons testing at Bikini Atoll as part of Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity in July 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices since the ...

in 1946. One of Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

James Forrestal

James Vincent Forrestal (February 15, 1892 – May 22, 1949) was the last Cabinet-level United States Secretary of the Navy and the first United States Secretary of Defense.

Forrestal came from a very strict middle-class Irish Catholic f ...

's aides, Lewis Strauss, proposed this series of tests to refute "loose talk to the effect that the fleet is obsolete in the face of this new weapon". The nuclear weapons were handmade devices, and a great deal of work remained to improve their ease of assembly, safety, reliability and storage before they were ready for production. There were also many improvements to their performance that had been suggested or recommended, but not possible under the pressure of wartime development.

Groves's biggest concern was about people. Soldiers and scientists wanted to return to their peacetime pursuits, and there was a danger that wartime knowledge would be lost, leaving no one who knew how to handle and maintain nuclear weapons, much less how to improve the weapons and processes. The military side of the Manhattan Project had relied heavily on reservist

A reservist is a person who is a member of a military reserve force. They are otherwise civilians, and in peacetime have careers outside the military. Reservists usually go for training on an annual basis to refresh their skills. This person i ...

s, as the policy of the Corps of Engineers was to assign regular officers to field commands. The reservists were now eligible for separation. To replace them, Groves asked for fifty West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

graduates from the top ten percent of their classes to man bomb-assembly teams at Sandia Base, where the assembly staff and facilities had been moved from Los Alamos and Wendover Field

Wendover is a market town and civil parish at the foot of the Chiltern Hills in Buckinghamshire, England. It is situated at the point where the main road across the Chilterns between London and Aylesbury intersects with the once important road ...

in September and October 1945. He felt that only such high-quality personnel would be able to work with the scientists who were currently doing the job. They were also urgently required for many other jobs in the postwar Army. When General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

Thomas T. Handy

Thomas Troy Handy (March 11, 1892 – April 12, 1982) was a United States Army four-star general who served as Deputy Chief of Staff, United States Army from 1944 to 1947; Commanding General, Fourth United States Army from 1947 to 1949; Commande ...

turned down his request, Groves raised the matter with the Chief of Staff of the Army, General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower, who similarly did not approve it. Groves then went over his head too, and took the issue to the Secretary of War, Robert P. Patterson, who agreed with Groves. The personnel manned the 2761st Engineer Battalion (Special), which became a field unit under the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project (AFSWP).

Groves hoped a new, permanent agency would be created to take over the responsibilities of the wartime Manhattan Project in 1945, but passage of the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 through Congress took much longer than expected, and involved considerable debate about the proper role of the military with respect to the development, production and control of nuclear weapons. The act that was signed by President Harry S. Truman on 1 August 1946 created a civilian agency, the United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President ...

(AEC), to take over the functions and assets of the Manhattan Project, but the commissioners were not appointed until October, and AEC did not assume its role until 1 January 1947. In the meantime, the Military Appropriation Act of 1946 gave the Manhattan Project $72.4million for research and development, and $19million for housing and utilities at Los Alamos and Oak Ridge.

The Atomic Energy Act provided for a Military Liaison Committee to advise the AEC on military matters, so Patterson appointed Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Lewis H. Brereton, who became chairman, along with Major General Lunsford E. Oliver and Colonel John H. Hinds as Army members of the Military Liaison Committee; Forrestal appointed Rear Admirals

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarded ...

Thorvald A. Solberg

Rear Admiral Thorvald A. Solberg (17 February 1894 – 16 May 1964) was a senior officer in the United States Navy, and the Chief of the Office of Naval Research from 1948 to 1951.

Biography

Thorvald A. Solberg was born in Mason, Wisconsin, on 1 ...

, Ralph A. Ofstie and William S. Parsons

Rear Admiral William Sterling "Deak" Parsons (26 November 1901 – 5 December 1953) was an American naval officer who worked as an ordnance expert on the Manhattan Project during World War II. He is best known for being the weaponeer on the ''En ...

as its naval members.

Organization

Chester W. Nimitz

Chester William Nimitz (; February 24, 1885 – February 20, 1966) was a fleet admiral in the United States Navy. He played a major role in the naval history of World War II as Commander in Chief, US Pacific Fleet, and Commander in C ...

appointed Groves as head of the AFSWP, with Parsons as his deputy. Accordingly, Groves was appointed to the Military Liaison Committee, although the newly appointed AEC chairman, David E. Lilienthal

David Eli Lilienthal (July 8, 1899 – January 15, 1981) was an American attorney and public administrator, best known for his Presidential Appointment to head Tennessee Valley Authority and later the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). He had p ...

, told Patterson he did not think it was a good idea, because Groves had run the Manhattan Project by himself for four years, and was not used to having to compromise.

Groves and Parsons drafted a proposed organization and charter for the AFSWP, which they sent to Eisenhower and Nimitz for approval in July 1947. Groves did not get everything he asked for; he wanted a status equal to that of a deputy to the Chief of Staff and Chief of Naval Operations, but the most Eisenhower and Nimitz would allow was a status equal to that of the heads of a technical service, although Groves still reported directly to them. They also characterized his role as a staff post rather than a command, although Groves was already exercising the functions of a commander at Sandia. After the National Security Act of 1947

The National Security Act of 1947 ( Pub.L.br>80-253 61 Stat.br>495 enacted July 26, 1947) was a law enacting major restructuring of the United States government's military and intelligence agencies following World War II. The majority of the prov ...

created an independent Air Force, Groves reported to the Chief of Staff of the Air Force as well, and was given a second deputy chief from the Air Force, Major General Roscoe C. Wilson, who had worked on the Silverplate

Silverplate was the code reference for the United States Army Air Forces' participation in the Manhattan Project during World War II. Originally the name for the aircraft modification project which enabled a B-29 Superfortress bomber to drop ...

project during the war.

Groves initially established the headquarters of the AFSWP in the old offices of the Manhattan Project on the fifth floor of the New War Department Building in Washington, DC, but on 15 April 1947 it moved to the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As a symbol of the U.S. military, the phrase ''The Pentagon'' is often used as a metonym ...

. As AFSWP headquarters expanded, it filled up its original accommodation, and began using office space in other parts of the building, which was not satisfactory from a security point of view. In August 1949, it moved to of new offices inside the Pentagon. This included space for a soundproof conference room, a darkroom, and vaults where its records and films were stored.

The 2761st Engineer Battalion (Special) at Sandia was commanded by

The 2761st Engineer Battalion (Special) at Sandia was commanded by Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

Gilbert M. Dorland, and consisted of a headquarters company, a security company (Company A), a bomb assembly company (Company B) and a radiological monitoring company (Company C), although Company C was never fully formed. For training purposes, Company B was initially divided into command, electrical, mechanical and nuclear groups, but the intention was to create three integrated 36-man bomb assembly teams. To free the bomb assembly teams from having to train newcomers, a Technical Training Group (TTG) was created under Lieutenant Colonel John A. Ord, a Signal Corps officer with a Doctor of Science

Doctor of Science ( la, links=no, Scientiae Doctor), usually abbreviated Sc.D., D.Sc., S.D., or D.S., is an academic research degree awarded in a number of countries throughout the world. In some countries, "Doctor of Science" is the degree used f ...

degree from Carnegie Institute of Technology who had directed the training of thousands of radar technicians at the Southern Signal Corps School during the war. The battalion was redesignated the 38th Engineer Battalion (Special) in April 1947, and in July it became part of the newly created AFSWP Field Command, under the command of Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed t ...

Robert M. Montague. The TTG was soon reporting directly to Montague as well.

The first bomb assembly team was formed in August 1947, followed by a second in December and a third in March 1948. Experience with assembling the bombs convincingly demonstrated the requirement, in Sandia if not in Washington, for a much larger unit. Groves reluctantly approved a 109-man special weapons unit, and Montague converted the three lettered companies of the 38th Engineer Battalion into special weapons units. In 1948, they began training a Navy special weapons unit, as the Navy foresaw delivery of nuclear weapons with its new North American AJ Savage bombers from its s. This unit became the 471st Naval Special Weapons Unit on its certification in August 1948. Two Air Force units were created in September and December 1948, which became the 502d and 508th Aviation Squadrons. An additional Army special weapons unit was created in May 1948, and in December, the 38th Engineer Battalion (Special) became the 8460th Special Weapons Group, with all seven special weapons units under its command. The four Army units were then renamed the 111th, 122d, 133d and 144th Special Weapons Units. During the late 1940s the Air Force gradually became the major user of nuclear weapons, and by the end of 1949 it had twelve assembly units and another three in training. The Army had only four and the Navy three, one for each ''Midway''-class carriers.

In March 1948, the Chief of Staff of the Air Force, General Carl Spaatz, proposed that the Air Force take over the AFSWP, on the grounds that the Key West Agreement had given it responsibility for strategic bombing. This would have simplified command of the AFSWP, as it would have been answerable to only one service chief instead of three. The Army cautiously supported the proposal, but the Navy was strongly opposed, fearing that the Air Force's confusion of atomic bombing and strategic bombing would impede or even prevent the Navy from having access to nuclear weapons, which it felt was necessary to accomplish its primary maritime mission. Another series of talks was held at the Naval War College

The Naval War College (NWC or NAVWARCOL) is the staff college and "Home of Thought" for the United States Navy at Naval Station Newport in Newport, Rhode Island. The NWC educates and develops leaders, supports defining the future Navy and associ ...

in Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and northeast of New ...

, from 20 to 22 August 1948, which resulted in the Newport Agreement, under which the Navy agreed to drop its opposition to the AFSWP being placed under the Air Force temporarily, in return for the Air Force recognizing the Navy's requirement for nuclear weapons. When the Air Force moved to make the temporary arrangement permanent in September 1948, the Army and Navy objected, and the Military Liaison Committee directed that the AFSWP should remain a tri-service organization answerable to the three service chiefs.

Field operations

Groves and the wartime director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, Robert Oppenheimer, had begun the move of ordnance functions to Sandia in late 1945. The laboratory's ordnance-engineering division, known as Z Division, after its first director, Jerrold R. Zacharias, was split between Los Alamos and Sandia. Between March and July 1946, Z Division relocated to Sandia, except for its mechanical engineering (Z-4) section, which followed in February 1947. Z Division worked on improving the mechanical and electrical reliability of the Mark 3Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki#Bombing of Nagasaki, detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second ...

bomb, but this work was disrupted by the Crossroads tests.

phase transition

In chemistry, thermodynamics, and other related fields, a phase transition (or phase change) is the physical process of transition between one state of a medium and another. Commonly the term is used to refer to changes among the basic states ...

to a different allotrope of plutonium. They had to be periodically inspected by technicians wearing gloves and respirators. The bomb's electrical power for its radar fuzes and detonators came from a pair of lead-acid batteries similar to those used in cars. These had to be charged 24 hours before use. After a few days the bomb had to be partially disassembled so they could be re-charged (and, only three days after that, replaced).

The 38th Engineer Battalion's electrical group studied the batteries, the electrical firing systems and the radar fuzes which detonated the bomb at the required altitude. The mechanical group dealt with the exploding-bridgewire detonators and the explosive lenses. The nuclear group moved to Los Alamos to study the cores and initiators. As part of their training, they attended lectures by Edward Teller, Hans Bethe,

The 38th Engineer Battalion's electrical group studied the batteries, the electrical firing systems and the radar fuzes which detonated the bomb at the required altitude. The mechanical group dealt with the exploding-bridgewire detonators and the explosive lenses. The nuclear group moved to Los Alamos to study the cores and initiators. As part of their training, they attended lectures by Edward Teller, Hans Bethe, Lise Meitner

Elise Meitner ( , ; 7 November 1878 – 27 October 1968) was an Austrian-Swedish physicist who was one of those responsible for the discovery of the element protactinium and nuclear fission. While working at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute on ra ...

and Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" an ...

. The electrical and mechanical groups at Sandia, although not the nuclear group, completed their training around the end of October 1946 and spent the next month devising the best methods of assembling a Fat Man, drawing up detailed checklists so later bomb assembly teams could be trained. They also drew up a proposed table of organization and equipment for an assembly team. It took two weeks for them to assemble their first bomb in December 1946.

Most of 1947 was spent planning for a field exercise in which a bomb team would deploy to a base and assemble weapons under field conditions. A by portable building was acquired and outfitted as field workshops that could be loaded onto a C-54

The Douglas C-54 Skymaster is a four-engined transport aircraft used by the United States Army Air Forces in World War II and the Korean War. Like the Douglas C-47 Skytrain derived from the DC-3, the C-54 Skymaster was derived from a civilian ...

or C-97 transport aircraft. In November 1947, the 38th Engineer Battalion carried out its first major field exercise, Operation Ajax. It drew bomb components, except for fissile cores, from the AEC, and deployed by air to Wendover Field, Utah. This was the home of the 509th Bombardment Group

5 (five) is a number, numeral and digit. It is the natural number, and cardinal number, following 4 and preceding 6, and is a prime number. It has attained significance throughout history in part because typical humans have five digits on eac ...

, which was the only unit operating Silverplate B-29 bombers, and therefore the only B-29 group capable of delivering nuclear weapons. To simulate operational conditions, they took a roundabout route via New England and Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a port, seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the county seat, seat of King County, Washington, King County, Washington (state), Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in bo ...

. Over the following ten days, they assembled bombs and flew training missions with them, including a live drop at the Naval Ordnance Test Station at Inyokern, California

Inyokern (formerly Siding 16 and Magnolia) is a census-designated place (CDP) in Kern County, California, United States. Its name derives from its location near the border between Inyo and Kern Counties. Inyokern is located west of Ridgecrest, at ...

.

This was followed by other exercises. In one exercise in March 1948, the base personnel successfully fought off an "attack" by 250 paratroopers from Fort Hood, Texas. In another exercise in November 1948, the 471st Special Weapons Unit flew to Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. Incorporated in 1705, it had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 cen ...

, and practiced bomb assembly on board the ''Midway''-class aircraft carriers.

Nuclear testing

In addition to assembly of weapons, the AFSWP supported nuclear weapons testing. For Operation Sandstone in 1948, Groves ordered Dorland to fill every possible job with his men. He did this so well that Strauss, now an AEC commissioner, became disturbed at the number of AFSWP personnel who were participating, and feared that the

In addition to assembly of weapons, the AFSWP supported nuclear weapons testing. For Operation Sandstone in 1948, Groves ordered Dorland to fill every possible job with his men. He did this so well that Strauss, now an AEC commissioner, became disturbed at the number of AFSWP personnel who were participating, and feared that the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

might launch a sneak attack on Enewetak to wipe out the nation's ability to assemble nuclear weapons. The successful testing in Operation Sandstone was a major leap forward. The new Mark 4 nuclear bomb the AEC began delivering in 1949 was a production design that was much easier to assemble and maintain, and enabled a bomb-assembly team to be reduced to just 46 men. Kenneth D. Nichols, the wartime commander of the Manhattan District, now "recommended that we should be thinking in terms of thousands of weapons rather than hundreds".

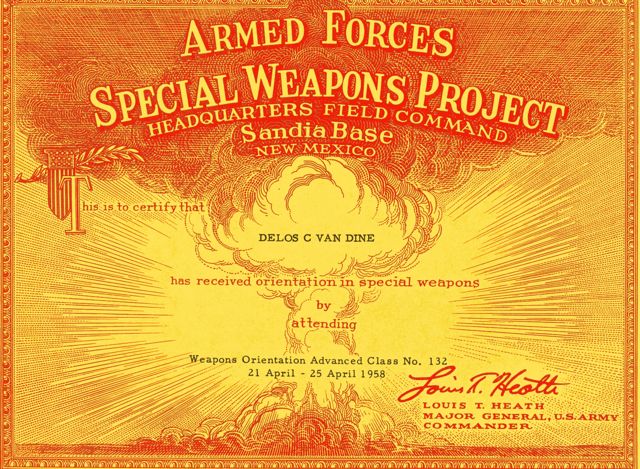

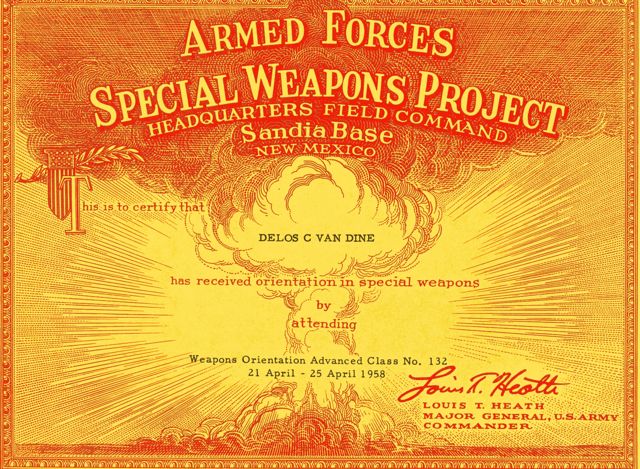

After Operation Sandstone, only relatively small numbers of AFSWP personnel were involved in nuclear testing. The AFSWP was heavily involved in the planning, preparation and coordination of tests, but it had limited participation in the tests themselves, where the bomb-assembly function was usually undertaken by scientists. During Operation Buster-Jangle, AFSWP personnel showed films and gave lectures to 2,800 military personnel who had been selected to witness the test, explaining what would occur and the procedures to be followed. This was expanded to cater for the more than 7,000 personnel who were involved in Operation Upshot–Knothole in 1953.

Custody of nuclear weapons

When the AEC was formed in 1947 it acquired custody of nuclear components from the Manhattan Project on the understanding that the matter would be reviewed. In November 1947, the Military Liaison Committee requested that custody of the nuclear stockpile be transferred to the military, but Lilienthal believed AEC custody of the stockpile was an important aspect of civilian control of nuclear weapons. He was disturbed that the AFSWP had not informed the AEC in advance of Operation Ajax. For his part, Groves suspected the AEC was not keeping bomb components in the condition in which the military wanted to receive them, and Operation Ajax only confirmed his suspicions. Reviewing the exercise, Montague reported that "under the existing law, with the AEC charged with procurement and custody of all atomic weapons, there was no adequate logistic support for the weapon." He recommended a larger role for the military, a recommendation with which Groves concurred, but was powerless to implement. Groves retired at the end of February 1948, and Nichols was designated as his successor with the rank of major general. At the same time, Forrestal, now the Secretary of Defense, reorganized the Military Liaison Committee. A civilian, Donald F. Carpenter, replaced Brereton as chairman, and there were now two members from each of the three services. On 11 March, Truman summoned Lilienthal, Nichols and Secretary of the Army

Groves retired at the end of February 1948, and Nichols was designated as his successor with the rank of major general. At the same time, Forrestal, now the Secretary of Defense, reorganized the Military Liaison Committee. A civilian, Donald F. Carpenter, replaced Brereton as chairman, and there were now two members from each of the three services. On 11 March, Truman summoned Lilienthal, Nichols and Secretary of the Army Kenneth C. Royall

Kenneth Claiborne Royall, Sr. (July 24, 1894May 25, 1971) was a U.S. Army general, and the last man to hold the office of Secretary of War, which secretariat was abolished in 1947. Royall served as the first Secretary of the Army from 1947 to 19 ...

to his office, and told them he expected the AFSWP and the AEC to cooperate.

Nichols's position was the same as Groves's and Montague's: that nuclear weapons needed to be available in an emergency, and the men who had to use them in battle needed to have experience with their maintenance, storage and handling. Norris Bradbury, who had replaced Oppenheimer as the director of the Los Alamos Laboratory in December 1945, argued that rapid transfer could be accomplished by improved procedures and that the other difficulties could best be resolved by further development, mostly from the scientists. Forrestal and Carpenter took the matter up with Truman, who issued his decision on 21 July 1948: "I regard the continued control of all aspects of the atomic energy program, including research, development and the custody of atomic weapons as the proper functions of the civil authorities."

With the outbreak of the Korean War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Korean War

, partof = the Cold War and the Korean conflict

, image = Korean War Montage 2.png

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Clockwise from top: ...

in 1950, air transport resources were put under great strain, and it was decided to reduce the requirement for it by pre-positioning non-nuclear components at locations in Europe and the Pacific. That way, in an emergency, only the nuclear components would have to be flown out. In June, Truman ordered the transfer of 90 sets of non-nuclear Mark4 components to the AFSWP for training purposes. In December, he authorized the carriage of non-nuclear components on board the ''Midway''-class carriers. In April 1951, the AEC released nine Mark4 weapons to the Air Force in case the Soviet Union intervened in the war in Korea. These were flown to Guam, where they were maintained by the Air Force special weapons unit there. Thus, at the end of 1951, there were 429 weapons in AEC custody and nine held by the Department of Defense.

In the light of this, a new AEC-AFSWP agreement on "Responsibilities of Stockpile Operations" was drawn up in August 1951, but in December, the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and t ...

began a new push for weapons to be permanently assigned to the armed forces, so as to ensure a greater degree of flexibility and a higher state of readiness. On 20 June 1953, Eisenhower, now as president, approved the deployment of nuclear components in equal numbers to non-nuclear components, and the Atomic Energy Act of 1954 amended the sections of the old act that gave exclusive custody to the AEC. By 1959, the nuclear stockpile had grown to 12,305 weapons of which 3,968 were in AEC custody and the remaining 8,337 were held by the Department of Defense. The total yield of the stockpile was now in excess of .

As Bradbury had promised, with research and development, nuclear weapons became smaller, simpler and lighter. They also became easier to store, assemble, test and maintain. Thus, while under Eisenhower's New Look policy the Armed Forces became more heavily involved with aspects of nuclear weapons than ever, the role of the AFSWP diminished. It began moving away from training assembly teams, which were increasingly not required, as its primary mission, and became more involved in the management of the rapidly growing nuclear stockpile, and providing technical advice and logistical support. In 1953, the AFSWP Field Command had 10,250 personnel. On 16 October 1953, the Secretary of Defense charged the AFSWP with responsibility for "a centralized system of reporting and accounting to ensure that the current status and location" of all nuclear weapons "will be known at all times". The Atomic Warfare Status Center was created within the AFSWP to handle this mission.

Conversion to Defense Atomic Support Agency

In April 1958, Eisenhower asked Congress for legislation to overhaul the Department of Defense. Over a decade had passed since the legislation which had established it, and he was concerned about the degree of inter-service rivalry, duplication and mismanagement that was evident in many programs. Inballistic missile

A ballistic missile is a type of missile that uses projectile motion to deliver warheads on a target. These weapons are guided only during relatively brief periods—most of the flight is unpowered. Short-range ballistic missiles stay within ...

development, the Soviet Sputnik program had demonstrated that country's technological lead over the United States. The Army and Air Force had rival programs, PGM-19 Jupiter and PGM-17 Thor

The PGM-17A Thor was the first operational ballistic missile of the United States Air Force (USAF). Named after the Norse god of thunder, it was deployed in the United Kingdom between 1959 and September 1963 as an intermediate-range ballistic mi ...

respectively, and the additional cost to the taxpayers of developing two systems instead of one was estimated at $500million.

The Defense Reorganization Act of 1958 was signed by Eisenhower in August 1958. It increased the authority of the Secretary of Defense, who was authorized to establish such defense agencies as he thought necessary "to provide for more effective, efficient and economical administration and operation". The first field agency established under the act was the Defense Atomic Support Agency (DASA). The new agency reported to the Secretary of Defense through the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and was given responsibility for the supervision of all Department of Defense nuclear sites. Otherwise, known as Top Secret military expeditionary instillation such as Sandia Base, Manzano Base, Bossier Base Clarksville Base, Killeen Base and Lake Mead Base to name a few its role and organization remained much the same, and its commander, Rear Admiral Edward N. Parker, remained as its first director. Eisenhower's proposed nuclear testing moratorium ultimately fundamentally changed DASA's mission, as nuclear testing was phased out, Cold War tensions eased, and nuclear disarmament became a prospect.

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* {{Featured article Government agencies established in 1947 1959 disestablishments in the United States Nuclear history of the United States Nuclear weapons program of the United States 1947 establishments in the United States Defunct organizations based in Washington, D.C.