Argument (linguistics) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In linguistics, an argument is an expression that helps complete the meaning of a predicate, the latter referring in this context to a main verb and its auxiliaries. In this regard, the '' complement'' is a closely related concept. Most predicates take one, two, or three arguments. A predicate and its arguments form a ''predicate-argument structure''. The discussion of predicates and arguments is associated most with (content) verbs and noun phrases (NPs), although other

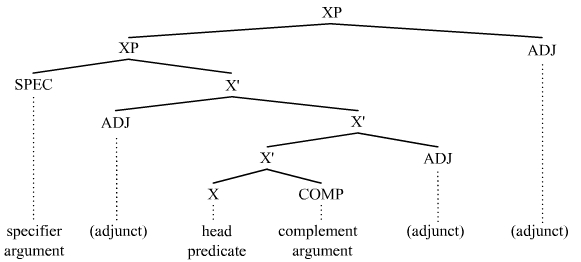

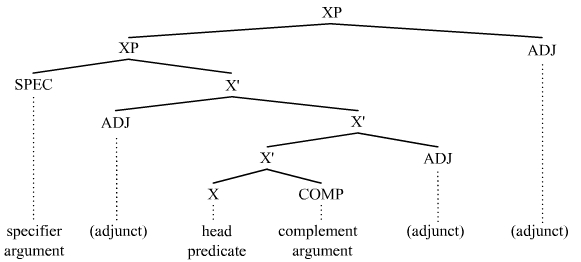

The complement argument appears as a sister of the head X, and the specifier argument appears as a daughter of XP. The optional adjuncts appear in one of a number of positions adjoined to a bar-projection of X or to XP.

Theories of syntax that acknowledge n-ary branching structures and hence construe syntactic structure as being flatter than the layered structures associated with the X-bar schema must employ some other means to distinguish between arguments and adjuncts. In this regard, some

The complement argument appears as a sister of the head X, and the specifier argument appears as a daughter of XP. The optional adjuncts appear in one of a number of positions adjoined to a bar-projection of X or to XP.

Theories of syntax that acknowledge n-ary branching structures and hence construe syntactic structure as being flatter than the layered structures associated with the X-bar schema must employ some other means to distinguish between arguments and adjuncts. In this regard, some  The arrow edges in the tree identify four constituents (= complete subtrees) as adjuncts: ''At one time'', ''actually'', ''in congress'', and ''for fun''. The normal dependency edges (= non-arrows) identify the other constituents as arguments of their heads. Thus ''Sam'', ''a duck'', and ''to his representative in congress'' are identified as arguments of the verbal predicate ''wanted to send''.

The arrow edges in the tree identify four constituents (= complete subtrees) as adjuncts: ''At one time'', ''actually'', ''in congress'', and ''for fun''. The normal dependency edges (= non-arrows) identify the other constituents as arguments of their heads. Thus ''Sam'', ''a duck'', and ''to his representative in congress'' are identified as arguments of the verbal predicate ''wanted to send''.

Analyzing syntax: A lexical-functional approach

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. *Osborne, T. and T. Gro√ü 2012. Constructions are catenae: Construction Grammar meets dependency grammar. Cognitive Linguistics 23, 1, 163-214. *Tesni√®re, L. 1959. √Čl√©ments de syntaxe structurale. Paris: Klincksieck. *Tesni√®re, L. 1969. √Čl√©ments de syntaxe structurale. 2nd edition. Paris: Klincksieck. {{refend Grammar Syntactic entities Transitivity and valency hu:Vonzat

syntactic categories A syntactic category is a syntactic unit that theories of syntax assume. Word classes, largely corresponding to traditional parts of speech (e.g. noun, verb, preposition, etc.), are syntactic categories. In phrase structure grammars, the ''phrasal c ...

can also be construed as predicates and as arguments. Arguments must be distinguished from adjuncts

In brewing, adjuncts are unmalted grains (such as corn, rice, rye, oats, barley, and wheat) or grain products used in brewing beer which supplement the main mash ingredient (such as malted barley). This is often done with the intention of cut ...

. While a predicate needs its arguments to complete its meaning, the adjuncts that appear with a predicate are optional; they are not necessary to complete the meaning of the predicate. Most theories of syntax and semantics acknowledge arguments and adjuncts, although the terminology varies, and the distinction is generally believed to exist in all languages. Dependency grammar

Dependency grammar (DG) is a class of modern grammatical theories that are all based on the dependency relation (as opposed to the ''constituency relation'' of phrase structure) and that can be traced back primarily to the work of Lucien Tesni√ ...

s sometimes call arguments ''actants'', following Lucien Tesnière (1959).

The area of grammar that explores the nature of predicates, their arguments, and adjuncts is called valency theory. Predicates have a valence; they determine the number and type of arguments that can or must appear in their environment. The valence of predicates is also investigated in terms of subcategorization.

Arguments and adjuncts

The basic analysis of the syntax and semantics of clauses relies heavily on the distinction between arguments andadjunct

Adjunct may refer to:

* Adjunct (grammar), words used as modifiers

* Adjunct professor, a rank of university professor

* Adjuncts, sources of sugar used in brewing

* Adjunct therapy used to complement another main therapeutic agent, either to impr ...

s. The clause predicate, which is often a content verb, demands certain arguments. That is, the arguments are necessary in order to complete the meaning of the verb. The adjuncts that appear, in contrast, are not necessary in this sense. The subject phrase and object phrase are the two most frequently occurring arguments of verbal predicates. For instance:

::Jill likes Jack.

::Sam fried the meat.

::The old man helped the young man.

Each of these sentences contains two arguments (in bold), the first noun (phrase) being the subject argument, and the second the object argument. ''Jill'', for example, is the subject argument of the predicate ''likes'', and ''Jack'' is its object argument. Verbal predicates that demand just a subject argument (e.g. ''sleep'', ''work'', ''relax'') are intransitive, verbal predicates that demand an object argument as well (e.g. ''like'', ''fry'', ''help'') are transitive, and verbal predicates that demand two object arguments are ditransitive

In grammar, a ditransitive (or bitransitive) verb is a transitive verb whose contextual use corresponds to a subject and two objects which refer to a theme and a recipient. According to certain linguistics considerations, these objects may be ...

(e.g. ''give'', ''lend'').

When additional information is added to our three example sentences, one is dealing with adjuncts, e.g.

::Jill really likes Jack.

::Jill likes Jack most of the time.

::Jill likes Jack when the sun shines.

::Jill likes Jack because he's friendly.

The added phrases (in bold) are adjuncts; they provide additional information that is not necessary to complete the meaning of the predicate ''likes''. One key difference between arguments and adjuncts is that the appearance of a given argument is often obligatory, whereas adjuncts appear optionally. While typical verb arguments are subject or object nouns or noun phrases as in the examples above, they can also be prepositional phrases (PPs) (or even other categories). The PPs in bold in the following sentences are arguments:

::Sam put the pen on the chair.

::Larry does not put up with that.

::Bill is getting on my case.

We know that these PPs are (or contain) arguments because when we attempt to omit them, the result is unacceptable:

:: *Sam put the pen.

:: *Larry does not put up.

:: *Bill is getting.

Subject and object arguments are known as ''core arguments''; core arguments can be suppressed, added, or exchanged in different ways, using voice operations like passivization, antipassivization, applicativization, incorporation

Incorporation may refer to:

* Incorporation (business), the creation of a corporation

* Incorporation of a place, creation of municipal corporation such as a city or county

* Incorporation (academic), awarding a degree based on the student having ...

, etc. Prepositional arguments, which are also called ''oblique arguments'', however, do not tend to undergo the same processes.

Psycholinguistic (argument vs adjuncts)

Psycholinguistic theories must explain how syntactic representations are built incrementally during sentence comprehension. One view that has sprung from psycholinguistics is the argument structure hypothesis (ASH), which explains the distinct cognitive operations for argument and adjunct attachment: arguments are attached via the lexical mechanism, but adjuncts are attached using general (non-lexical) grammatical knowledge that is represented as phrase structure rules or the equivalent. Argument status determines the cognitive mechanism in which a phrase will be attached to the developing syntactic representations of a sentence. Psycholinguistic evidence supports a formal distinction between arguments and adjuncts, for any questions about the argument status of a phrase are, in effect, questions about learned mental representations of the lexical heads.Syntactic vs. semantic arguments

An important distinction acknowledges both syntactic and semantic arguments. Content verbs determine the number and type of syntactic arguments that can or must appear in their environment; they impose specific syntactic functions (e.g. subject, object, oblique, specific preposition, possessor, etc.) onto their arguments. These syntactic functions will vary as the form of the predicate varies (e.g. active verb, passive participle, gerund, nominal, etc.). In languages that have morphological case, the arguments of a predicate must appear with the correct case markings (e.g. nominative, accusative, dative, genitive, etc.) imposed on them by their predicate. The semantic arguments of the predicate, in contrast, remain consistent, e.g. ::Jack is liked by Jill. ::Jill's liking Jack ::Jack's being liked by Jill ::the liking of Jack by Jill ::Jill's like for Jack The predicate 'like' appears in various forms in these examples, which means that the syntactic functions of the arguments associated with ''Jack'' and ''Jill'' vary. The object of the active sentence, for instance, becomes the subject of the passive sentence. Despite this variation in syntactic functions, the arguments remain semantically consistent. In each case, ''Jill'' is the experiencer (= the one doing the liking) and ''Jack'' is the one being experienced (= the one being liked). In other words, the syntactic arguments are subject to syntactic variation in terms of syntactic functions, whereas the thematic roles of the arguments of the given predicate remain consistent as the form of that predicate changes. The syntactic arguments of a given verb can also vary across languages. For example, the verb ''put'' in English requires three syntactic arguments: subject, object, locative (e. g. ''He put the book into the box''). These syntactic arguments correspond to the three semantic arguments agent, theme, and goal. The Japanese verb ''oku'' 'put', in contrast, has the same three semantic arguments, but the syntactic arguments differ, since Japanese does not require three syntactic arguments, so it is correct to say ''Kare ga hon o oita'' ("He put the book"). The equivalent sentence in English is ungrammatical without the required locative argument, as the examples involving ''put'' above demonstrate. For this reason, a slight paraphrase is required to render the nearest grammatical equivalent in English: ''He positioned the book'' or ''He deposited the book''.Distinguishing between arguments and adjuncts

Arguments vs. adjuncts

A large body of literature has been devoted to distinguishing arguments from adjuncts. Numerous syntactic tests have been devised for this purpose. One such test is the relative clause diagnostic. If the test constituent can appear after the combination ''which occurred/happened'' in a relative clause, it is an adjunct, not an argument, e.g. ::Bill left on Tuesday. ‚Üí Bill left, which happened on Tuesday. ‚Äď ''on Tuesday'' is an adjunct. ::Susan stopped due to the weather. ‚Üí Susan stopped, which occurred due to the weather. ‚Äď ''due to the weather'' is an adjunct. ::Fred tried to say something twice. ‚Üí Fred tried to say something, which occurred twice. ‚Äď ''twice'' is an adjunct. The same diagnostic results in unacceptable relative clauses (and sentences) when the test constituent is an argument, e.g. ::Bill left home. ‚Üí *Bill left, which happened home. ‚Äď ''home'' is an argument. ::Susan stopped her objections. ‚Üí *Susan stopped, which occurred her objections. ‚Äď ''her objections'' is an argument. ::Fred tried to say something. ‚Üí *Fred tried to say, which happened something. ‚Äď ''something'' is an argument. This test succeeds in identifying prepositional arguments as well: ::We are waiting for Susan. ‚Üí *We are waiting, which is happening for Susan. ‚Äď ''for Susan'' is an argument. ::Tom put the knife in the drawer. ‚Üí *Tom put the knife, which occurred in the drawer. ‚Äď ''in the drawer'' is an argument. ::We laughed at you. ‚Üí *We laughed, which occurred at you. ‚Äď ''at you'' is an argument. The utility of the relative clause test is, however, limited. It incorrectly suggests, for instance, that modal adverbs (e.g. ''probably'', ''certainly'', ''maybe'') and manner expressions (e.g. ''quickly'', ''carefully'', ''totally'') are arguments. If a constituent passes the relative clause test, however, one can be sure that it is ''not'' an argument.Obligatory vs. optional arguments

A further division blurs the line between arguments and adjuncts. Many arguments behave like adjuncts with respect to another diagnostic, the omission diagnostic. Adjuncts can always be omitted from the phrase, clause, or sentence in which they appear without rendering the resulting expression unacceptable. Some arguments (obligatory ones), in contrast, cannot be omitted. There are many other arguments, however, that are identified as arguments by the relative clause diagnostic but that can nevertheless be omitted, e.g. ::a. She cleaned the kitchen. ::b. She cleaned. ‚Äď ''the kitchen'' is an optional argument. ::a. We are waiting for Larry. ::b. We are waiting. ‚Äď ''for Larry'' is an optional argument. ::a. Susan was working on the model. ::b. Susan was working. ‚Äď ''on the model'' is an optional argument. The relative clause diagnostic would identify the constituents in bold as arguments. The omission diagnostic here, however, demonstrates that they are not obligatory arguments. They are, rather, optional. The insight, then, is that a three-way division is needed. On the one hand, one distinguishes between arguments and adjuncts, and on the other hand, one allows for a further division between obligatory and optional arguments.Arguments and adjuncts in noun phrases

Most work on the distinction between arguments and adjuncts has been conducted at the clause level and has focused on arguments and adjuncts to verbal predicates. The distinction is crucial for the analysis of noun phrases as well, however. If it is altered somewhat, the relative clause diagnostic can also be used to distinguish arguments from adjuncts in noun phrases, e.g. ::Bill's bold reading of the poem after lunch ::: *bold reading of the poem after lunch that was Bill's ‚Äď ''Bill's'' is an argument. ::: Bill's reading of the poem after lunch that was bold ‚Äď ''bold'' is an adjunct ::: *Bill's bold reading after lunch that was of the poem ‚Äď ''of the poem'' is an argument ::: Bill's bold reading of the poem that was after lunch ‚Äď ''after lunch'' is an adjunct The diagnostic identifies ''Bill's'' and ''of the poem'' as arguments, and ''bold'' and ''after lunch'' as adjuncts.Representing arguments and adjuncts

The distinction between arguments and adjuncts is often indicated in the tree structures used to represent syntactic structure. In phrase structure grammars, an adjunct is "adjoined" to a projection of its head predicate in such a manner that distinguishes it from the arguments of that predicate. The distinction is quite visible in theories that employ the X-bar schema, e.g. :: The complement argument appears as a sister of the head X, and the specifier argument appears as a daughter of XP. The optional adjuncts appear in one of a number of positions adjoined to a bar-projection of X or to XP.

Theories of syntax that acknowledge n-ary branching structures and hence construe syntactic structure as being flatter than the layered structures associated with the X-bar schema must employ some other means to distinguish between arguments and adjuncts. In this regard, some

The complement argument appears as a sister of the head X, and the specifier argument appears as a daughter of XP. The optional adjuncts appear in one of a number of positions adjoined to a bar-projection of X or to XP.

Theories of syntax that acknowledge n-ary branching structures and hence construe syntactic structure as being flatter than the layered structures associated with the X-bar schema must employ some other means to distinguish between arguments and adjuncts. In this regard, some dependency grammar

Dependency grammar (DG) is a class of modern grammatical theories that are all based on the dependency relation (as opposed to the ''constituency relation'' of phrase structure) and that can be traced back primarily to the work of Lucien Tesni√ ...

s employ an arrow convention. Arguments receive a "normal" dependency edge, whereas adjuncts receive an arrow edge. In the following tree, an arrow points away from an adjunct toward the governor of that adjunct:

:: The arrow edges in the tree identify four constituents (= complete subtrees) as adjuncts: ''At one time'', ''actually'', ''in congress'', and ''for fun''. The normal dependency edges (= non-arrows) identify the other constituents as arguments of their heads. Thus ''Sam'', ''a duck'', and ''to his representative in congress'' are identified as arguments of the verbal predicate ''wanted to send''.

The arrow edges in the tree identify four constituents (= complete subtrees) as adjuncts: ''At one time'', ''actually'', ''in congress'', and ''for fun''. The normal dependency edges (= non-arrows) identify the other constituents as arguments of their heads. Thus ''Sam'', ''a duck'', and ''to his representative in congress'' are identified as arguments of the verbal predicate ''wanted to send''.

Relevant theories

* Argumentation theory Argumentation theory focuses on how logical reasoning leads to end results through an internal structure built of premises, a method of reasoning and a conclusion. There are many versions of argumentation that relate to this theory that include: conversational, mathematical, scientific, interpretive, legal, and political. * Grammar theory Grammar theory, specifically functional theories of grammar, relate to the functions of language as the link to fully understanding linguistics by referencing grammar elements to their functions and purposes. *Syntax

In linguistics, syntax () is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, hierarchical sentence structure ( constituency) ...

theories

A variety of theories exist regarding the structure of syntax, including generative grammar, categorial grammar, and dependency grammar

Dependency grammar (DG) is a class of modern grammatical theories that are all based on the dependency relation (as opposed to the ''constituency relation'' of phrase structure) and that can be traced back primarily to the work of Lucien Tesni√ ...

.

* Theories in semantics

Modern theories of semantics include formal semantics, lexical semantics, and computational semantics. Formal semantics focuses on truth conditioning. Lexical Semantics delves into word meanings in relation to their context and computational semantics uses algorithms and architectures to investigate linguistic meanings.

* Valence theory

The concept of valence is the number and type of arguments that are linked to a predicate, in particular to a verb. In valence theory verbs' arguments include also the argument expressed by the subject of the verb.

History of argument linguistics

The notion of argument structure was first conceived in the 1980s by researchers working in the government‚Äďbinding framework to help address controversies about arguments.Importance

The distinction between arguments and adjuncts is crucial to most theories of syntax and grammar. Arguments behave differently from adjuncts in numerous ways. Theories of binding,coordination

Coordination may refer to:

* Coordination (linguistics), a compound grammatical construction

* Coordination complex, consisting of a central atom or ion and a surrounding array of bound molecules or ions

* Coordination number or ligancy of a centr ...

, discontinuities, ellipsis, etc. must acknowledge and build on the distinction. When one examines these areas of syntax, what one finds is that arguments consistently behave differently from adjuncts and that without the distinction, our ability to investigate and understand these phenomena would be seriously hindered.

There is a distinction between arguments and adjuncts which isn't really noticed by many in everyday language. The difference is between obligatory phrases versus phrases which embellish a sentence. For instance, if someone says "Tim punched the stuffed animal", the phrase stuffed animal would be an argument because it is the main part of the sentence. If someone says, "Tim punched the stuffed animal with glee", the phrase with glee would be an adjunct because it just enhances the sentence and the sentence can stand alone without it.

See also

*Adjunct

Adjunct may refer to:

* Adjunct (grammar), words used as modifiers

* Adjunct professor, a rank of university professor

* Adjuncts, sources of sugar used in brewing

* Adjunct therapy used to complement another main therapeutic agent, either to impr ...

* Dependency grammar

Dependency grammar (DG) is a class of modern grammatical theories that are all based on the dependency relation (as opposed to the ''constituency relation'' of phrase structure) and that can be traced back primarily to the work of Lucien Tesni√ ...

* Meaning‚Äďtext theory

* Phrase structure grammar

* Predicate (grammar)

* Subcategorization frame

* Theta criterion

The theta-criterion (also named őł-criterion) is a constraint on x-bar theory that was first proposed by as a rule within the system of principles of the government and binding theory, called theta-theory (őł-theory). As theta-theory is concerned ...

* Theta role

* Valency

Valence or valency may refer to:

Science

* Valence (chemistry), a measure of an element's combining power with other atoms

* Degree (graph theory), also called the valency of a vertex in graph theory

* Valency (linguistics), aspect of verbs re ...

Notes

References

*√Āgel, V., L. Eichinger, H.-W. Eroms, P. Hellwig, H. Heringer, and H. Lobin (eds.) 2003/6. Dependency and valency: An international handbook of contemporary research. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. *Eroms, H.-W. 2000. Syntax der deutschen Sprache. Berlin: de Gruyter. *Kroeger, P. 2004Analyzing syntax: A lexical-functional approach

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. *Osborne, T. and T. Gro√ü 2012. Constructions are catenae: Construction Grammar meets dependency grammar. Cognitive Linguistics 23, 1, 163-214. *Tesni√®re, L. 1959. √Čl√©ments de syntaxe structurale. Paris: Klincksieck. *Tesni√®re, L. 1969. √Čl√©ments de syntaxe structurale. 2nd edition. Paris: Klincksieck. {{refend Grammar Syntactic entities Transitivity and valency hu:Vonzat