Arabian Astronomy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Islamic astronomy comprises the

Islamic astronomy comprises the

Al-Farabi had followed some of the same ideas as

Al-Farabi had followed some of the same ideas as

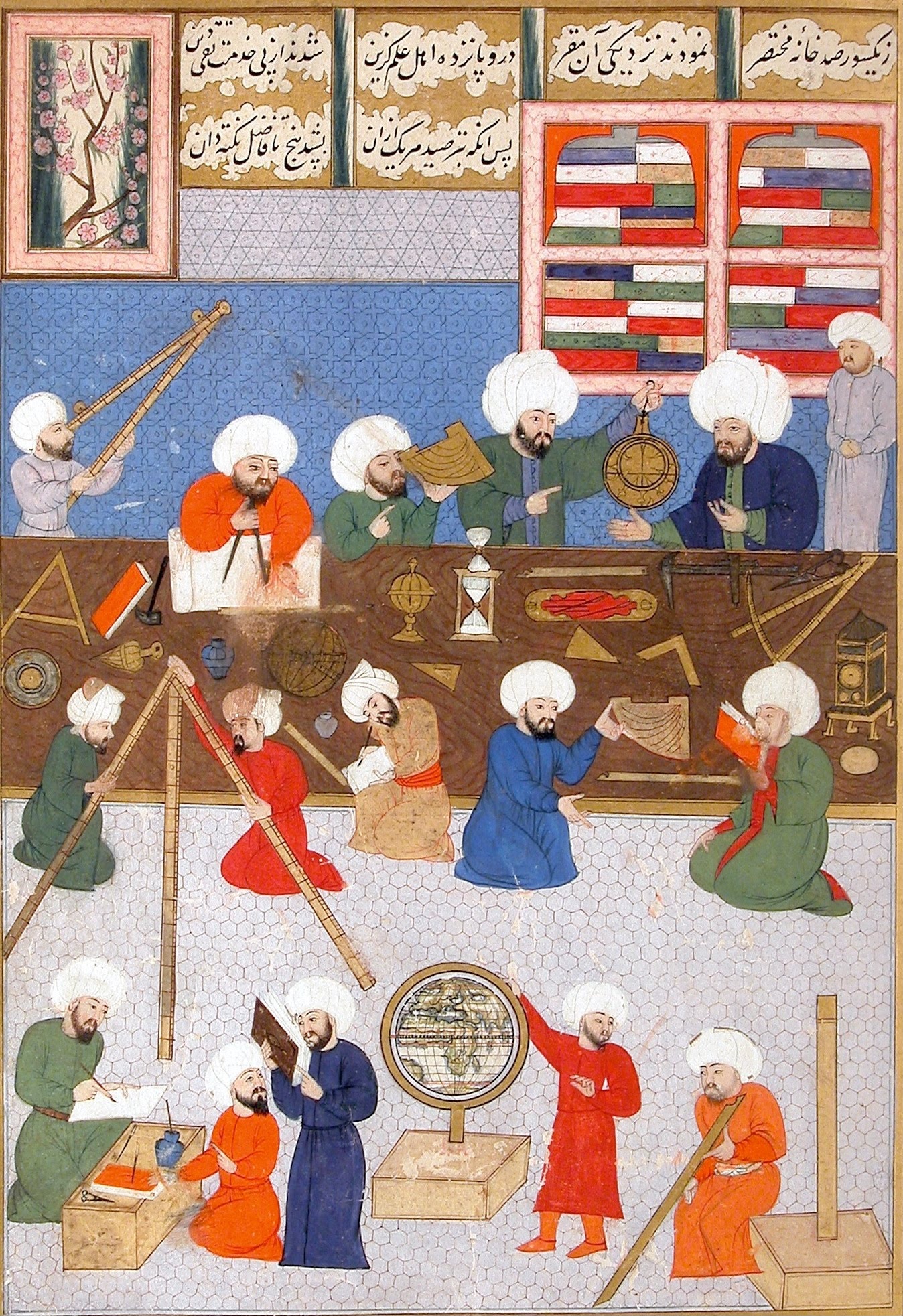

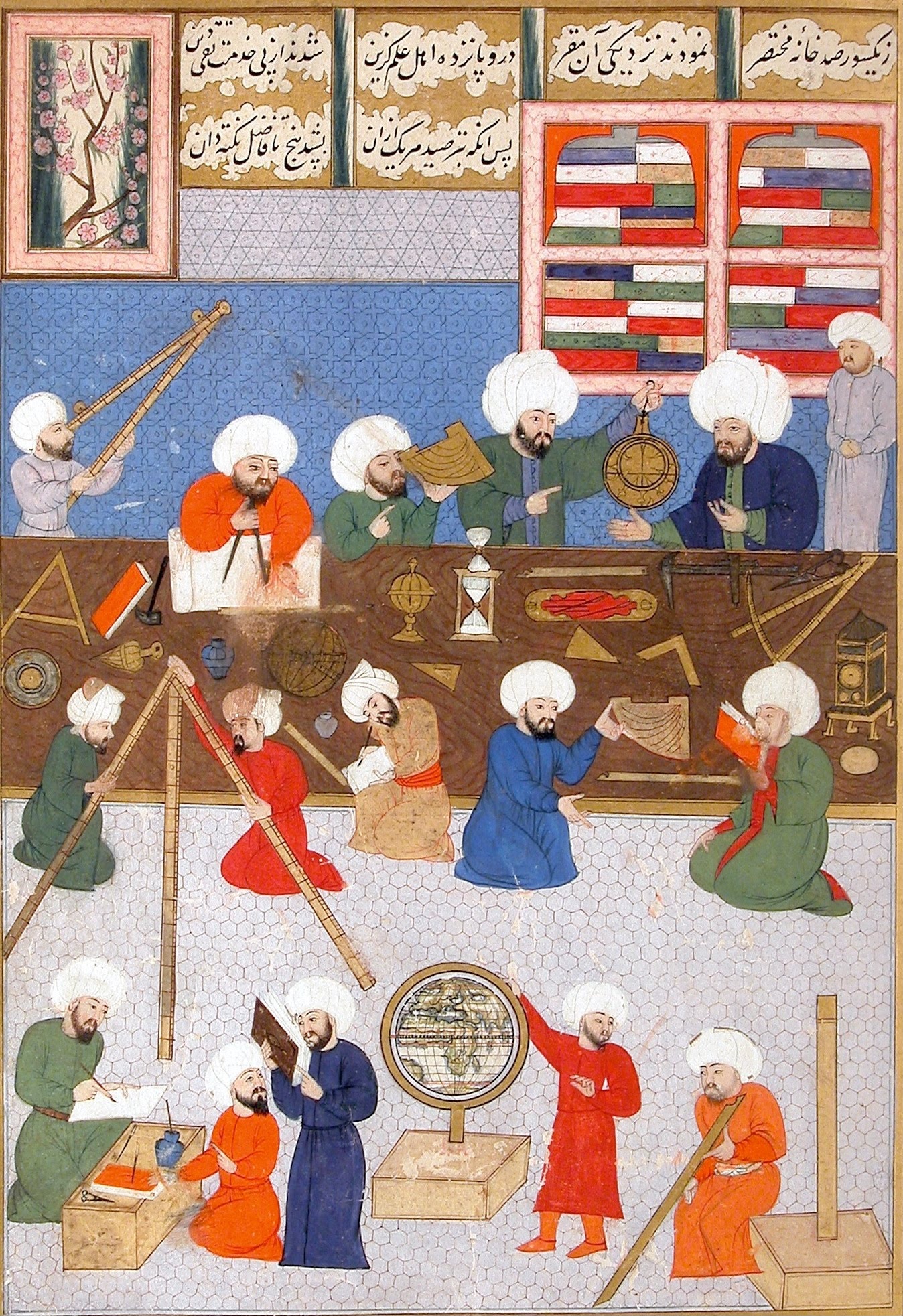

The House of Wisdom was an academy established in Baghdad under Abbasid caliph Al-Ma'mun in the early 9th century. Astronomical research was greatly supported by the

The House of Wisdom was an academy established in Baghdad under Abbasid caliph Al-Ma'mun in the early 9th century. Astronomical research was greatly supported by the

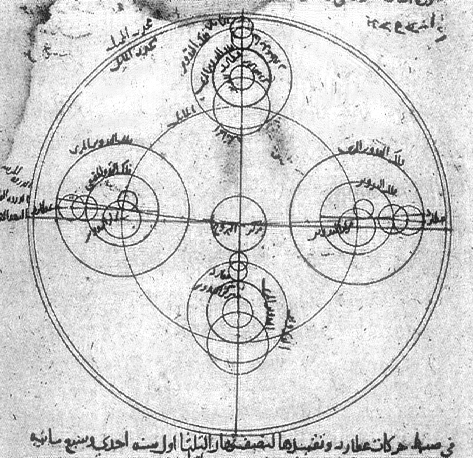

Nasir al-Din Tusi wanted to use the concept of Tusi couple to replace the "equant" concept in Ptolemic model. Since the equant concept would result in the moon distance to change dramatically through each month, at least by the factor of two if the math is done. But with the Tusi couple, the moon would just rotate around Earth resulting in the correct observation and applied concept.

Nasir al-Din Tusi wanted to use the concept of Tusi couple to replace the "equant" concept in Ptolemic model. Since the equant concept would result in the moon distance to change dramatically through each month, at least by the factor of two if the math is done. But with the Tusi couple, the moon would just rotate around Earth resulting in the correct observation and applied concept.

/ref>

Several works of Islamic astronomy were translated to Latin starting from the 12th century.

The work of

Several works of Islamic astronomy were translated to Latin starting from the 12th century.

The work of

pp. 263–64)

di Bono (1995), Veselovsky (1973). Copernicus explicitly references several astronomers of the "

Islamic influence on Chinese astronomy was first recorded during the

Islamic influence on Chinese astronomy was first recorded during the

In the early Joseon dynasty, Joseon period, the Islamic calendar served as a basis for calendar reform being more accurate than the existing Chinese-based calendars. A Korean translation of the ''Huihui Lifa'', a text combining

In the early Joseon dynasty, Joseon period, the Islamic calendar served as a basis for calendar reform being more accurate than the existing Chinese-based calendars. A Korean translation of the ''Huihui Lifa'', a text combining

The first systematic observations in Islam are reported to have taken place under the patronage of

The first systematic observations in Islam are reported to have taken place under the patronage of  In 1420, prince

In 1420, prince

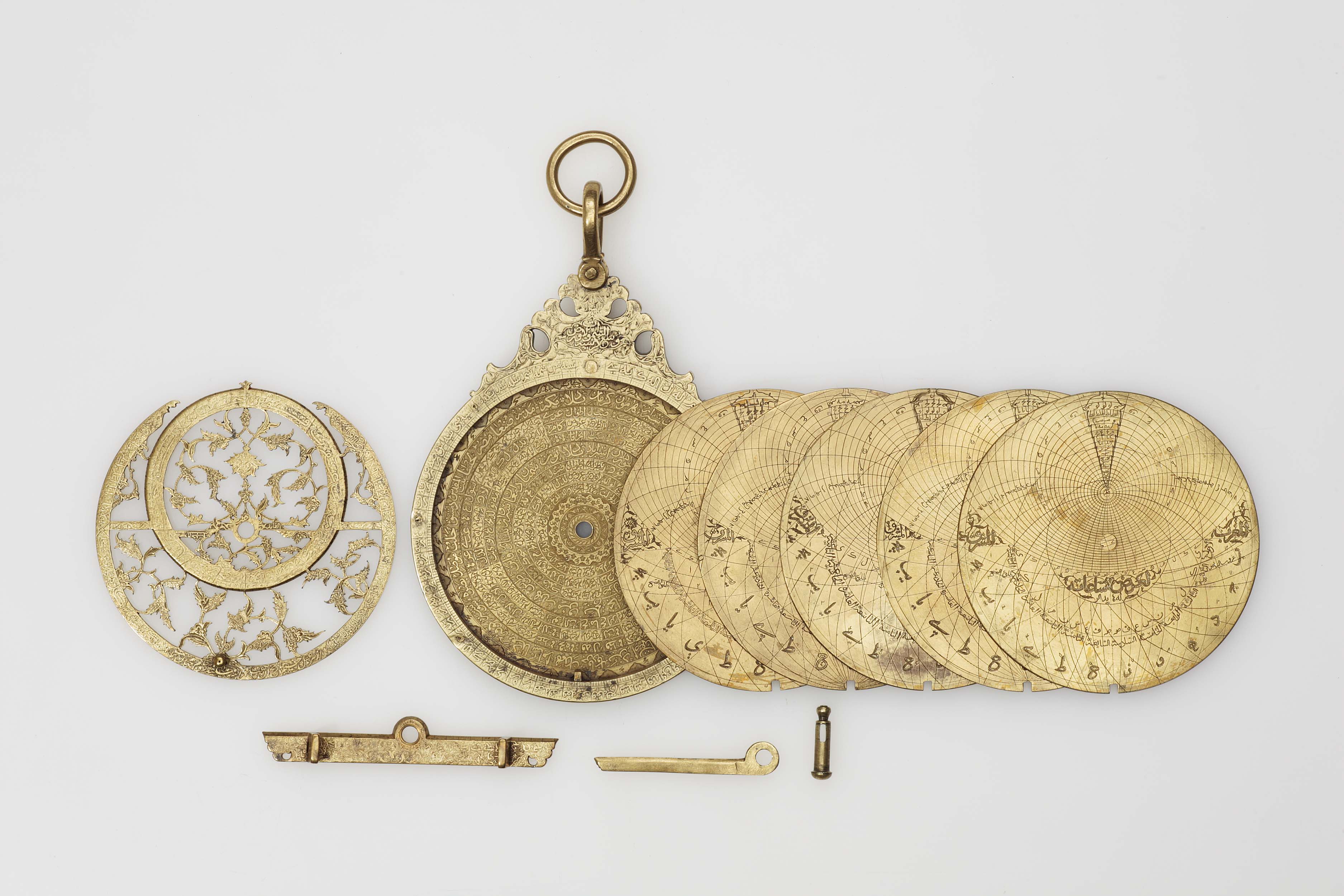

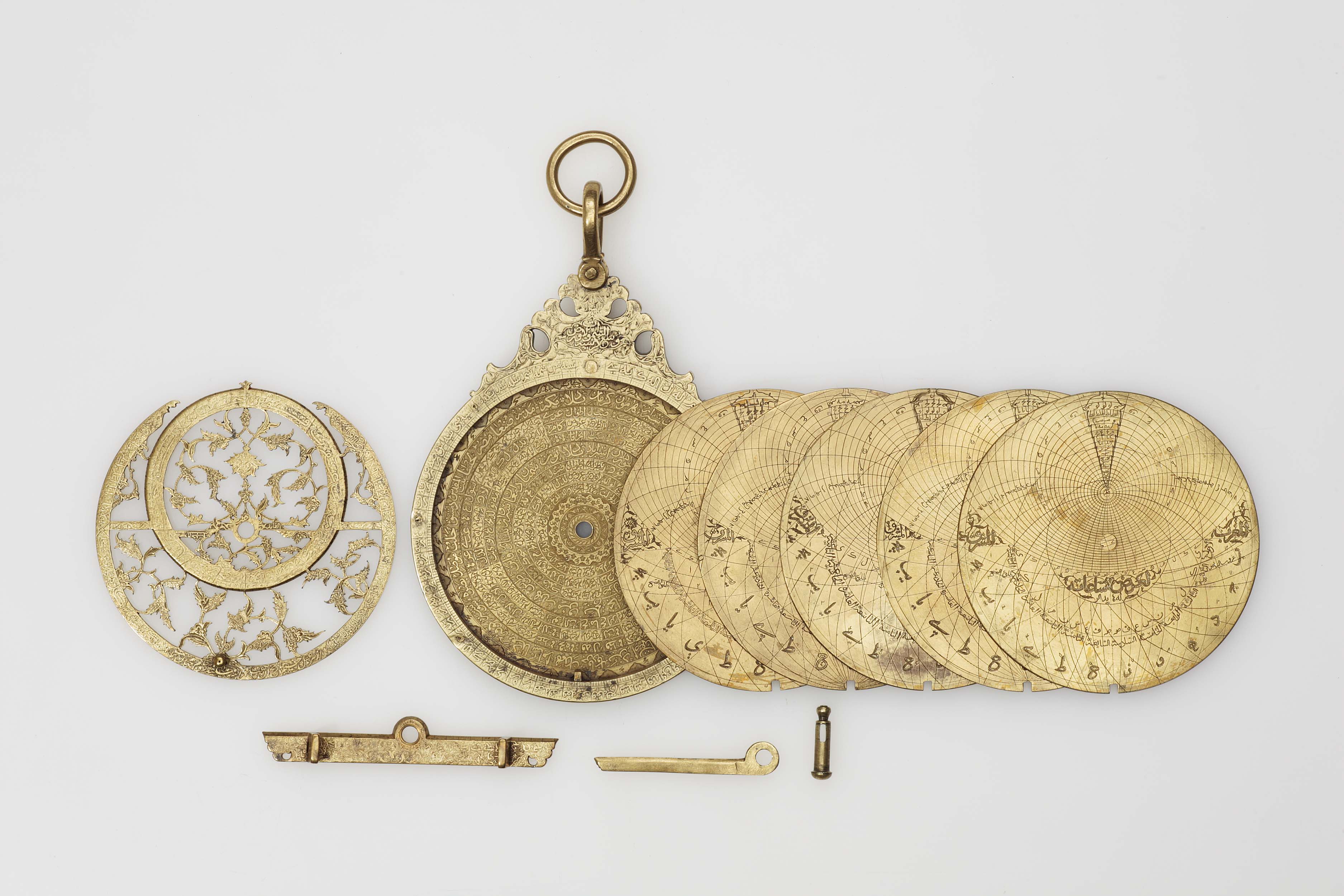

Celestial globes were used primarily for solving problems in celestial astronomy. Today, 126 such instruments remain worldwide, the oldest from the 11th century. The altitude of the Sun, or the Right Ascension and Declination of stars could be calculated with these by inputting the location of the observer on the meridian ring of the globe. The initial blueprint for a portable celestial globe to measure celestial coordinates came from Spanish Muslim astronomer Jabir ibn Aflah (d. 1145). Another skillful Muslim astronomer working on celestial globes was Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi (b. 903), whose treatise the ''Book of Fixed Stars'' describes how to design the constellation images on the globe, as well as how to use the celestial globe. However, it was in Iraq in the 10th century that astronomer Al-Battani was working on celestial globes to record celestial data. This was different because up until then, the traditional use for a celestial globe was as an observational instrument. Al-Battani's treatise describes in detail the plotting coordinates for 1,022 stars, as well as how the stars should be marked. An armillary sphere had similar applications. No early Islamic armillary spheres survive, but several treatises on "the instrument with the rings" were written. In this context there is also an Islamic development, the spherical astrolabe, of which only one complete instrument, from the 14th century, has survived.

Celestial globes were used primarily for solving problems in celestial astronomy. Today, 126 such instruments remain worldwide, the oldest from the 11th century. The altitude of the Sun, or the Right Ascension and Declination of stars could be calculated with these by inputting the location of the observer on the meridian ring of the globe. The initial blueprint for a portable celestial globe to measure celestial coordinates came from Spanish Muslim astronomer Jabir ibn Aflah (d. 1145). Another skillful Muslim astronomer working on celestial globes was Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi (b. 903), whose treatise the ''Book of Fixed Stars'' describes how to design the constellation images on the globe, as well as how to use the celestial globe. However, it was in Iraq in the 10th century that astronomer Al-Battani was working on celestial globes to record celestial data. This was different because up until then, the traditional use for a celestial globe was as an observational instrument. Al-Battani's treatise describes in detail the plotting coordinates for 1,022 stars, as well as how the stars should be marked. An armillary sphere had similar applications. No early Islamic armillary spheres survive, but several treatises on "the instrument with the rings" were written. In this context there is also an Islamic development, the spherical astrolabe, of which only one complete instrument, from the 14th century, has survived.

The astrolabe was arguably the most important instrument created and used for astronomical purposes in the medieval period. Its invention in early medieval times required immense study and much trial and error in order to find the right method of which to construct it to where it would work efficiently and consistently, and its invention led to several mathematic advances which came from the problems that arose from using the instrument. The astrolabe's original purpose was to allow one to find the altitudes of the sun and many visible stars, during the day and night, respectively. However, they have ultimately come to provide great contribution to the progress of mapping the globe, thus resulting in further exploration of the sea, which then resulted in a series of positive events that allowed the world we know today to come to be. The astrolabe has served many purposes over time, and it has shown to be quite a key factor from medieval times to the present.

The astrolabe, as mentioned before, required the use of mathematics, and the development of the instrument incorporated azimuth circles, which opened a series of questions on further mathematical dilemmas. Astrolabes served the purpose of finding the altitude of the sun, which also meant that they provided one the ability to find the direction of Muslim prayer (or the direction of Mecca). Aside from these perhaps more widely known purposes, the astrolabe has led to many other advances as well. One very important advance to note is the great influence it had on navigation, specifically in the marine world. This advancement is incredibly important because the calculation of latitude being made more simple not only allowed for the increase in sea exploration, but it eventually led to the Renaissance revolution, the increase in global trade activity, even the discovery of several of the world's continents.

The astrolabe was arguably the most important instrument created and used for astronomical purposes in the medieval period. Its invention in early medieval times required immense study and much trial and error in order to find the right method of which to construct it to where it would work efficiently and consistently, and its invention led to several mathematic advances which came from the problems that arose from using the instrument. The astrolabe's original purpose was to allow one to find the altitudes of the sun and many visible stars, during the day and night, respectively. However, they have ultimately come to provide great contribution to the progress of mapping the globe, thus resulting in further exploration of the sea, which then resulted in a series of positive events that allowed the world we know today to come to be. The astrolabe has served many purposes over time, and it has shown to be quite a key factor from medieval times to the present.

The astrolabe, as mentioned before, required the use of mathematics, and the development of the instrument incorporated azimuth circles, which opened a series of questions on further mathematical dilemmas. Astrolabes served the purpose of finding the altitude of the sun, which also meant that they provided one the ability to find the direction of Muslim prayer (or the direction of Mecca). Aside from these perhaps more widely known purposes, the astrolabe has led to many other advances as well. One very important advance to note is the great influence it had on navigation, specifically in the marine world. This advancement is incredibly important because the calculation of latitude being made more simple not only allowed for the increase in sea exploration, but it eventually led to the Renaissance revolution, the increase in global trade activity, even the discovery of several of the world's continents.

Muslims made several important improvements to the theory and construction of sundials, which they inherited from their Indian and Roman Greece, Greek predecessors. Khwarizmi made tables for these instruments which considerably shortened the time needed to make specific calculations.

Sundials were frequently placed on mosques to determine the time of prayer. One of the most striking examples was built in the fourteenth century by the ''muwaqqit'' (timekeeper) of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, ibn al-Shatir.

Muslims made several important improvements to the theory and construction of sundials, which they inherited from their Indian and Roman Greece, Greek predecessors. Khwarizmi made tables for these instruments which considerably shortened the time needed to make specific calculations.

Sundials were frequently placed on mosques to determine the time of prayer. One of the most striking examples was built in the fourteenth century by the ''muwaqqit'' (timekeeper) of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, ibn al-Shatir.

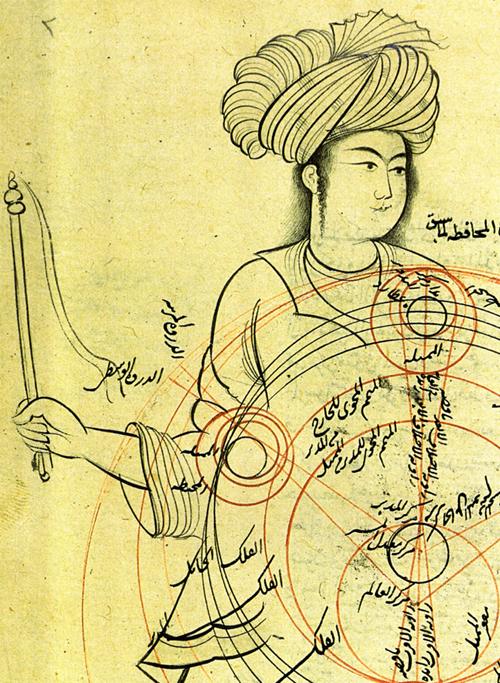

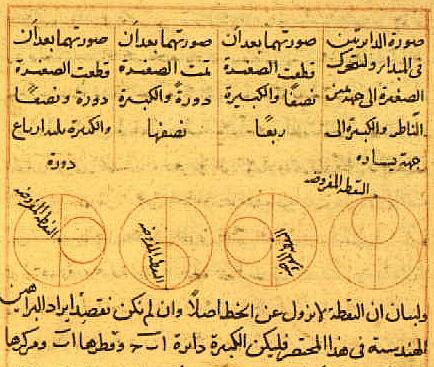

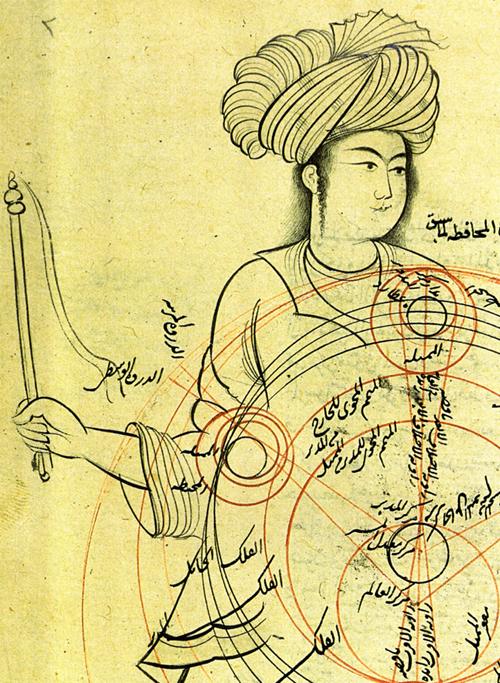

There are examples of cosmological imagery throughout many forms of Islamic art, whether that be manuscripts, ornately crafted astrological tools, or palace frescoes, just to name a few. Islamic art maintains the capability to reach every class and level of society.

Within Islamic cosmological doctrines and the Islamic study of astronomy, such as the Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Purity (alternatively called The Rasa'il of the Ikhwan al-Safa) there is a heavy emphasis by medieval scholars on the importance of the study of the heavens. This study of the heavens has translated into artistic representations of the universe and astrological concepts. There are many themes under which Islamic astrological art falls under, such as religious, political, and cultural contexts. It is posited by scholars that there are actually three waves or traditions of cosmological imagery, Western, Byzantine, and Islamic. The Islamic world gleaned inspiration from Greek, Iranian, and Indian methods in order to procure a unique representation of the stars and the universe.

There are examples of cosmological imagery throughout many forms of Islamic art, whether that be manuscripts, ornately crafted astrological tools, or palace frescoes, just to name a few. Islamic art maintains the capability to reach every class and level of society.

Within Islamic cosmological doctrines and the Islamic study of astronomy, such as the Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Purity (alternatively called The Rasa'il of the Ikhwan al-Safa) there is a heavy emphasis by medieval scholars on the importance of the study of the heavens. This study of the heavens has translated into artistic representations of the universe and astrological concepts. There are many themes under which Islamic astrological art falls under, such as religious, political, and cultural contexts. It is posited by scholars that there are actually three waves or traditions of cosmological imagery, Western, Byzantine, and Islamic. The Islamic world gleaned inspiration from Greek, Iranian, and Indian methods in order to procure a unique representation of the stars and the universe.

A place like Qasr Amra, Quasyr' Amra, which was used as a rural Umayyad palace and bath complex, coveys the way astrology and the cosmos have weaved their way into architectural design. During the time of its use, one could be resting in the bathhouse and gaze at the frescoed dome that would almost reveal a sacred and cosmic nature. Aside from the other frescoes of the complex which heavily focused on al-Walid, the bath dome was decorated in the Islamic zodiac and celestial designs. It would have almost been as if the room was suspended in space. In their encyclopedia, the Ikhwan al' Safa describe the Sun to have been placed at the center of the universe by God, and all other celestial bodies orbit around it in spheres. As a result, it would be as if whoever was sitting underneath this fresco would have been at the center of the universe, reminded of their power and position. A place like Qusayr' Amra represents the way astrological art and images interacted with Islamic elites and those who maintained caliphal authority.

The Islamic zodiac and astrological visuals have also been present in metalwork. Pitcher (container), Ewers depicting the twelve zodiac symbols exist in order to emphasize elite craftsmanship and carry blessings such as one example now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Coinage also carried zodiac imagery that bears the sole purpose of representing the month in which the coin was minted. As a result, astrological symbols could have been used as both decoration, and a means to communicate symbolic meanings or specific information.

A place like Qasr Amra, Quasyr' Amra, which was used as a rural Umayyad palace and bath complex, coveys the way astrology and the cosmos have weaved their way into architectural design. During the time of its use, one could be resting in the bathhouse and gaze at the frescoed dome that would almost reveal a sacred and cosmic nature. Aside from the other frescoes of the complex which heavily focused on al-Walid, the bath dome was decorated in the Islamic zodiac and celestial designs. It would have almost been as if the room was suspended in space. In their encyclopedia, the Ikhwan al' Safa describe the Sun to have been placed at the center of the universe by God, and all other celestial bodies orbit around it in spheres. As a result, it would be as if whoever was sitting underneath this fresco would have been at the center of the universe, reminded of their power and position. A place like Qusayr' Amra represents the way astrological art and images interacted with Islamic elites and those who maintained caliphal authority.

The Islamic zodiac and astrological visuals have also been present in metalwork. Pitcher (container), Ewers depicting the twelve zodiac symbols exist in order to emphasize elite craftsmanship and carry blessings such as one example now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Coinage also carried zodiac imagery that bears the sole purpose of representing the month in which the coin was minted. As a result, astrological symbols could have been used as both decoration, and a means to communicate symbolic meanings or specific information.

Donald Routledge Hill, Hill, Donald Routledge, ''Islamic Science And Engineering'', Edinburgh University Press (1993),

Donald Routledge Hill, Hill, Donald Routledge, ''Islamic Science And Engineering'', Edinburgh University Press (1993),

"Tubitak Turkish National Observatory Antalya"

The Arab Union for Astronomy and Space Sciences (AUASS)

King Abdul Aziz Observatory

{{Islamic studies Medieval astronomy History of astronomy, Medieval Islamic world Islamic Golden Age, Astronomy Astronomy in the medieval Islamic world,

Islamic astronomy comprises the

Islamic astronomy comprises the astronomical

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, galaxi ...

developments made in the Islamic world, particularly during the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

(9th–13th centuries), and mostly written in the Arabic language

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

. These developments mostly took place in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

, Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

, Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

, and North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, and later in the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

. It closely parallels the genesis of other Islamic science

Science in the medieval Islamic world was the science developed and practised during the Islamic Golden Age under the Umayyads of Córdoba, the Abbadids of Seville, the Samanids, the Ziyarids, the Buyids in Persia, the Abbasid Caliphate an ...

s in its assimilation of foreign material and the amalgamation of the disparate elements of that material to create a science with Islamic characteristics. These included Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, Sassanid

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

, and Indian works in particular, which were translated and built upon.

Islamic astronomy played a significant role in the revival of Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and EuropeanSaliba (1999). astronomy following the loss of knowledge during the early medieval period, notably with the production of Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

translations of Arabic works during the 12th century.

Islamic astronomy also had an influence on Chinese astronomy

Astronomy in China has a long history stretching from the Shang dynasty, being refined over a period of more than 3,000 years. The ancient Chinese people have identified stars from 1300 BCE, as Chinese star names later categorized in the twe ...

and Malian astronomy.

A significant number of stars in the sky, such as Aldebaran

Aldebaran (Arabic: “The Follower”, "الدبران") is the brightest star in the zodiac constellation of Taurus. It has the Bayer designation α Tauri, which is Latinized to Alpha Tauri and abbreviated Alpha Tau or α Tau. Alde ...

, Altair

Altair is the brightest star in the constellation of Aquila and the twelfth-brightest star in the night sky. It has the Bayer designation Alpha Aquilae, which is Latinised from α Aquilae and abbreviated Alpha Aql ...

and Deneb

Deneb () is a first-magnitude star in the constellation of Cygnus, the swan. Deneb is one of the vertices of the asterism known as the Summer Triangle and the "head" of the Northern Cross. It is the brightest star in Cygnus and th ...

, and astronomical terms such as alidade

An alidade () (archaic forms include alhidade, alhidad, alidad) or a turning board is a device that allows one to sight a distant object and use the line of sight to perform a task. This task can be, for example, to triangulate a scale map on site ...

, azimuth

An azimuth (; from ar, اَلسُّمُوت, as-sumūt, the directions) is an angular measurement in a spherical coordinate system. More specifically, it is the horizontal angle from a cardinal direction, most commonly north.

Mathematical ...

, and nadir

The nadir (, ; ar, نظير, naẓīr, counterpart) is the direction pointing directly ''below'' a particular location; that is, it is one of two vertical directions at a specified location, orthogonal to a horizontal flat surface.

The direc ...

, are still referred to by their Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

names. A large corpus of literature from Islamic astronomy remains today, numbering approximately 10,000 manuscripts scattered throughout the world, many of which have not been read or catalogued. Even so, a reasonably accurate picture of Islamic activity in the field of astronomy can be reconstructed.

History

Pre-Islamic Arabs

Ahmad Dallal

Ahmad S. Dallal () is a scholar of Islamic studies and an academic administrator. He is the current president of The American University in Cairo.

Biography

Dallal received his bachelor's degree in engineering from the American University of B ...

notes that, unlike the Babylonians, Greeks, and Indians, who had developed elaborate systems of mathematical astronomical study, the pre-Islamic Arabs relied entirely on empirical observations. These observations were based on the rising and setting of particular stars, and this indigenous constellation tradition was known as ''Anwā’''. The study of ''Anwā’'' continued to be developed after Islamization

Islamization, Islamicization, or Islamification ( ar, أسلمة, translit=aslamāh), refers to the process through which a society shifts towards the religion of Islam and becomes largely Muslim. Societal Islamization has historically occur ...

by the Arabs, where Islamic astronomers added mathematical methods to their empirical observations.Dallal (1999), pg. 162

Early Abbasid era

The first astronomical texts that were translated into Arabic were of Indian and Persian origin. The most notable of the texts was ''Zij al-Sindhind

''Zīj as-Sindhind'' (, ''Zīj as‐Sindhind al‐kabīr'', lit. "Great astronomical tables of the Sindhind"; from Sanskrit ''siddhānta'', "system" or "treatise") is a work of zij (astronomical handbook with tables used to calculate celestial po ...

'', an 8th-century Indian astronomical work that was translated by Muhammad ibn Ibrahim al-Fazari

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monoth ...

and Yaqub ibn Tariq after 770 CE with the assistance of Indian astronomers who visited the court of caliph Al-Mansur

Abū Jaʿfar ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad al-Manṣūr (; ar, أبو جعفر عبد الله بن محمد المنصور; 95 AH – 158 AH/714 CE – 6 October 775 CE) usually known simply as by his laqab Al-Manṣūr (المنصور) w ...

in 770. Another text translated was the ''Zij al-Shah'', a collection of astronomical tables (based on Indian parameters) compiled in Sasanid Persia over two centuries.

Fragments of texts during this period indicate that Arabs adopted the sine function (inherited from India) in place of the chords

Chord may refer to:

* Chord (music), an aggregate of musical pitches sounded simultaneously

** Guitar chord a chord played on a guitar, which has a particular tuning

* Chord (geometry), a line segment joining two points on a curve

* Chord ( ...

of arc used in Greek trigonometry.

According to David King, after the rise of Islam, the religious obligation to determine the qibla

The qibla ( ar, قِبْلَة, links=no, lit=direction, translit=qiblah) is the direction towards the Kaaba in the Sacred Mosque in Mecca, which is used by Muslims in various religious contexts, particularly the direction of prayer for the ...

and prayer times inspired progress in astronomy. Early Islam's history shows evidence of a productive relationship between faith and science. Specifically, Islamic scientists took an early interest in astronomy, as the concept of keeping time accurately was important for the five daily prayers central to the faith. Early Islamicate scientists constructed astronomical tables specifically to determine the exact times of prayer for specific locations around the continent, serving effectively as an early system of time zone

A time zone is an area which observes a uniform standard time for legal, commercial and social purposes. Time zones tend to follow the boundaries between countries and their subdivisions instead of strictly following longitude, because it ...

s.

Astronomical methods

Al-Farabi

Abu Nasr Muhammad Al-Farabi ( fa, ابونصر محمد فارابی), ( ar, أبو نصر محمد الفارابي), known in the West as Alpharabius; (c. 872 – between 14 December, 950 and 12 January, 951)PDF version was a renowned early Isl ...

(d. 950) was a philosopher who had a method of knowing what astronomy was. He describes mathematical astronomy but also can convey a sense of understanding of astronomy presented with music/optics. In a mathematical sense, astronomy can be broken up into three parts as explained by Al-Farabi. He shows that inhabited and uninhabited places on earth can be examined with astronomy how the earth moves and from day or night. Another is the movement of different Astronomical objects of where they move to, number of motions, and where they started. The third one is the shapes/sizes/positioning of the celestial bodies to obtain. Al-Farabi's believes that his idea of mathematical astronomy is separate from science. Such as physics dealing with the internal aspect of planets, what they can be made out of. Astronomy is restricted to the external aspect, such as positioning, shape, and size. This helps show how Al-Farabi's method of figuring out knowledge on what astronomy was can not correct. Namely to separate physics and astronomy as two separate sciences in order to discover more about the subject.

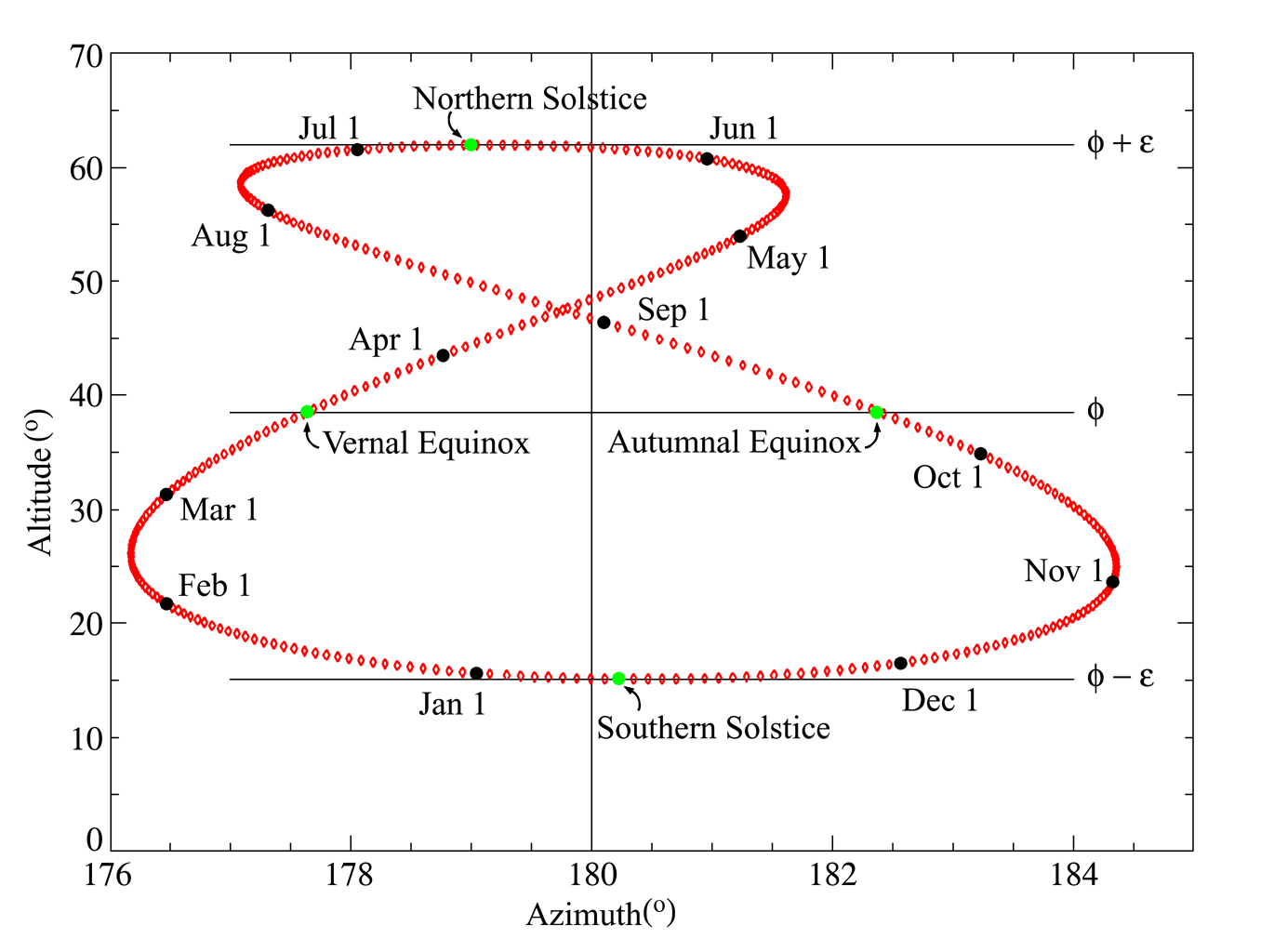

Al-Farabi had followed some of the same ideas as

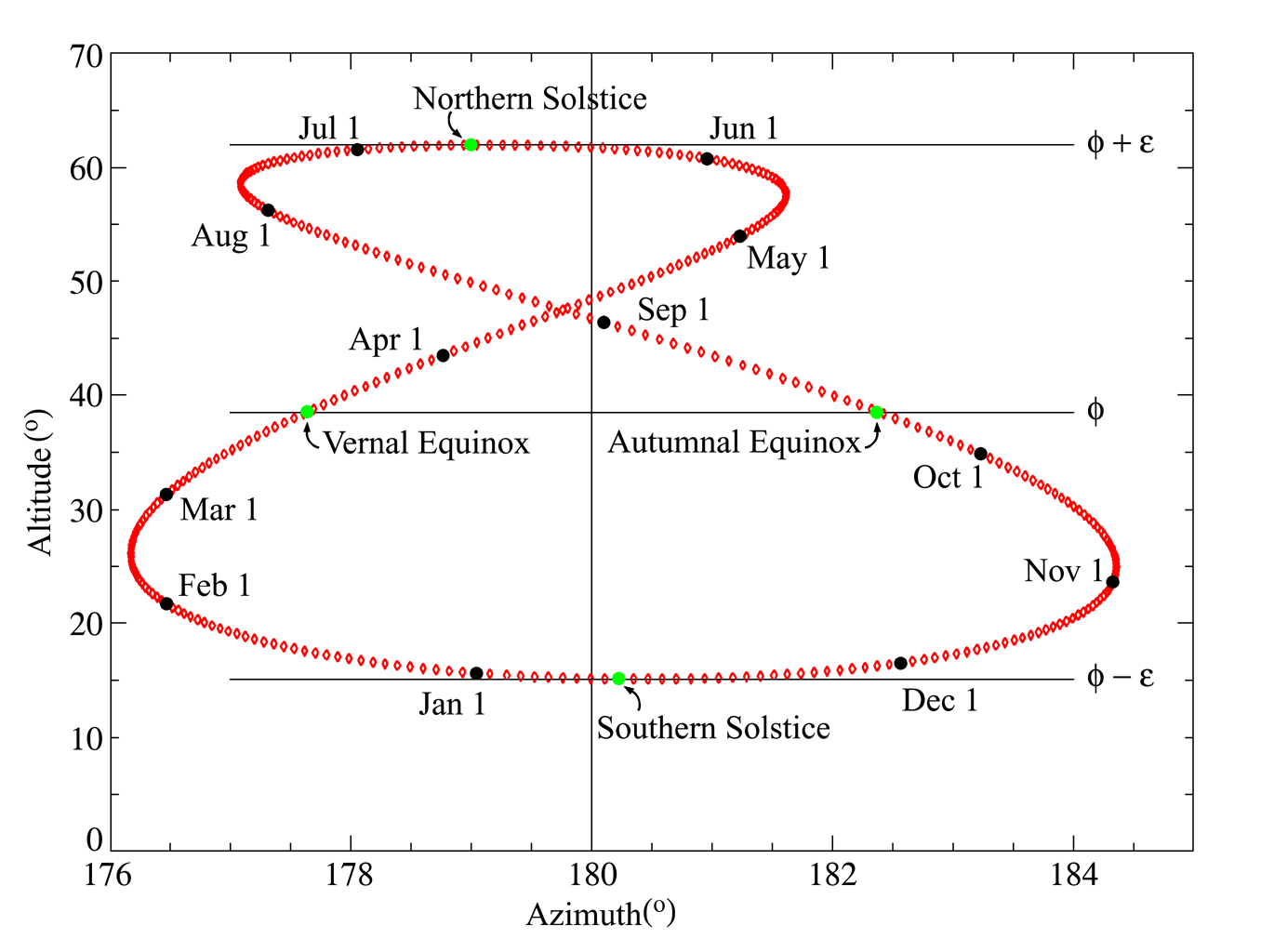

Al-Farabi had followed some of the same ideas as Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

. This was because Ptolemy enjoyed observations and only knew mathematics to be an accurate way of composing compelling reason. Rather than having to deal with physics and metaphysics because they were seen as unreliable to help prove theories of the universe. Ptolemy had a mathematical way of astronomy just as Al-Farabi. His way was called Analemma

In astronomy, an analemma (; ) is a diagram showing the position of the Sun in the sky as seen from a fixed location on Earth at the same mean solar time, as that position varies over the course of a year. The diagram will resemble a figure ...

, which is a way to calculate the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

s position from a fixed location. Within old historic texts, such as Vitruvius

Vitruvius (; c. 80–70 BC – after c. 15 BC) was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work entitled '' De architectura''. He originated the idea that all buildings should have three attribut ...

Architecture IX.7, and Hero of Alexandria's Dioptra 35, analemma's were drawn to help solve answers to problems that had to deal with geometry, possibly about astronomy. The analemma was shown to be one of Ptolemy's Hypothesis' for problem-solving. An analemma is very complicated and difficult to understand with multiple techniques on how to draw and perform the math of one. It was very common for many people to group the sundial and analemma together. Ptolemy's analemma helped the Islamic period thrive because it was used continuously to locate the sun.

Golden Age

The House of Wisdom was an academy established in Baghdad under Abbasid caliph Al-Ma'mun in the early 9th century. Astronomical research was greatly supported by the

The House of Wisdom was an academy established in Baghdad under Abbasid caliph Al-Ma'mun in the early 9th century. Astronomical research was greatly supported by the Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

al-Mamun

Abu al-Abbas Abdallah ibn Harun al-Rashid ( ar, أبو العباس عبد الله بن هارون الرشيد, Abū al-ʿAbbās ʿAbd Allāh ibn Hārūn ar-Rashīd; 14 September 786 – 9 August 833), better known by his regnal name Al-Ma'mu ...

through the House of Wisdom. Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon. I ...

and Damascus became the centers of such activity.

The first major Muslim work of astronomy was ''Zij al-Sindhind'' by mathematician al-Khwarizmi

Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī ( ar, محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي, Muḥammad ibn Musā al-Khwārazmi; ), or al-Khwarizmi, was a Persian polymath from Khwarazm, who produced vastly influential works in mathematics, astronom ...

in 830. The work contains tables for the movements of the Sun, the Moon, and the five planets known at the time. The work is significant as it introduced Ptolemaic concepts into Islamic sciences. This work also marks the turning point in Islamic astronomy. Hitherto, Muslim astronomers had adopted a primary research approach to the field, translating works of others and learning already discovered knowledge. Al-Khwarizmi's work marked the beginning of nontraditional methods of study and calculations.

Doubts on Ptolemy

In 850,al-Farghani

Abū al-ʿAbbās Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Kathīr al-Farghānī ( ar, أبو العبّاس أحمد بن محمد بن كثير الفرغاني 798/800/805–870), also known as Alfraganus in the West, was an astronomer in the Abbasid court ...

wrote ''Kitab fi Jawami'' (meaning "A compendium of the science of stars"). The book primarily gave a summary of Ptolemic cosmography. However, it also corrected Ptolemy based on the findings of earlier Arab astronomers. Al-Farghani gave revised values for the obliquity of the ecliptic

In astronomy, axial tilt, also known as obliquity, is the angle between an object's rotational axis and its orbital axis, which is the line perpendicular to its orbital plane; equivalently, it is the angle between its equatorial plane and o ...

, the precessional movement of the apogee

An apsis (; ) is the farthest or nearest point in the orbit of a planetary body about its primary body. For example, the apsides of the Earth are called the aphelion and perihelion.

General description

There are two apsides in any ell ...

s of the Sun and the Moon, and the circumference of the Earth. The book was widely circulated through the Muslim world, and translated into Latin.

By the 10th century texts appeared regularly whose subject matter was doubts concerning Ptolemy (''shukūk''). Several Muslim scholars questioned the Earth's apparent immobility and centrality within the universe. From this time, independent investigation into the Ptolemaic system

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, an ...

became possible. According to Dallal (2010), the use of parameters, sources and calculation methods from different scientific traditions made the Ptolemaic tradition "receptive right from the beginning to the possibility of observational refinement and mathematical restructuring".

Egyptian astronomer Ibn Yunus

Abu al-Hasan 'Ali ibn 'Abd al-Rahman ibn Ahmad ibn Yunus al-Sadafi al-Misri (Arabic: ابن يونس; c. 950 – 1009) was an important Egyptian astronomer and mathematician, whose works are noted for being ahead of their time, having been based ...

found fault in Ptolemy's calculations about the planet's movements and their peculiarity in the late 10th century. Ptolemy calculated that Earth's wobble, otherwise known as precession, varied 1 degree every 100 years. Ibn Yunus contradicted this finding by calculating that it was instead 1 degree every 70 years.

Between 1025 and 1028, Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the pri ...

wrote his ''Al-Shukuk ala Batlamyus'' (meaning "Doubts on Ptolemy"). While maintaining the physical reality of the geocentric model, he criticized elements of the Ptolemic models. Many astronomers took up the challenge posed in this work, namely to develop alternate models that resolved these difficulties. In 1070, Abu Ubayd al-Juzjani published the ''Tarik al-Aflak'' where he discussed the "equant" problem of the Ptolemic model and proposed a solution. In Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

, the anonymous work ''al-Istidrak ala Batlamyus'' (meaning "Recapitulation regarding Ptolemy"), included a list of objections to Ptolemic astronomy.

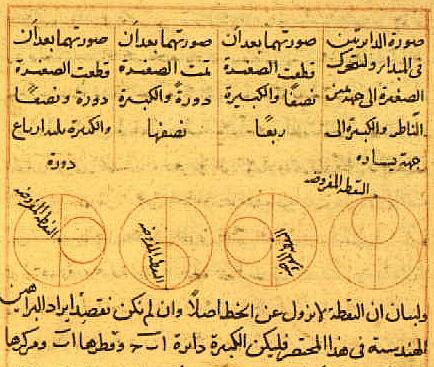

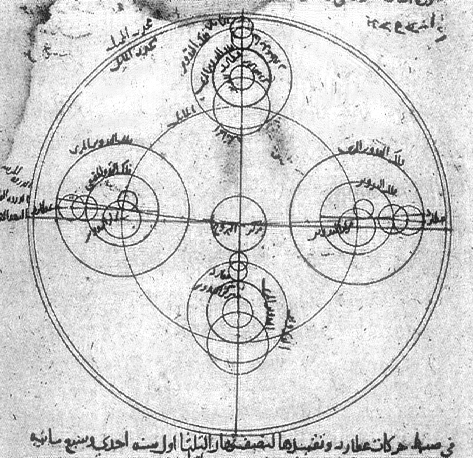

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, the creator of the Tusi couple

The Tusi couple is a mathematical device in which a small circle rotates inside a larger circle twice the diameter of the smaller circle. Rotations of the circles cause a point on the circumference of the smaller circle to oscillate back and fo ...

, also worked heavily to expose the problems present in Ptolemy's work. In 1261, Tusi published his Tadkhira, which contained 16 fundamental problems he found with Ptolemaic astronomy, and by doing this, set off a chain of Islamic scholars that would attempt to solve these problems. Scholars such as Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi

Qotb al-Din Mahmoud b. Zia al-Din Mas'ud b. Mosleh Shirazi (1236–1311) ( fa, قطبالدین محمود بن ضیاالدین مسعود بن مصلح شیرازی) was a 13th-century Persian polymath and poet who made contributions to a ...

, Ibn al-Shatir, and Shams al-Din al-Khafri

Shams al-Din Muhammad b. Ahmad al-Khafri al-Kashi (died 1550), known as Khafri, was an Iranian religious scholar and astronomer at the beginning of the Safavid dynasty. Before the arrival of Sheikh Baha'i in Iran, he was appointed as the major Sh ...

all worked to produce new models for solving Tusi's 16 Problems, and the models they worked to create would become widely adopted by astronomers for use in their own works.

Nasir al-Din Tusi wanted to use the concept of Tusi couple to replace the "equant" concept in Ptolemic model. Since the equant concept would result in the moon distance to change dramatically through each month, at least by the factor of two if the math is done. But with the Tusi couple, the moon would just rotate around Earth resulting in the correct observation and applied concept.

Nasir al-Din Tusi wanted to use the concept of Tusi couple to replace the "equant" concept in Ptolemic model. Since the equant concept would result in the moon distance to change dramatically through each month, at least by the factor of two if the math is done. But with the Tusi couple, the moon would just rotate around Earth resulting in the correct observation and applied concept. Mu'ayyad al-Din al-Urdi

Al-Urdi (full name: Moayad Al-Din Al-Urdi Al-Amiri Al-Dimashqi) () (d. 1266) was a medieval Syrian Arab astronomer and geometer.

Born circa 1200, presumably (from the nisba ''al‐ʿUrḍī'') in the village of ''ʿUrḍ'' in the Syrian desert ...

was another engineer/scholar that tried to make sense of the motion of planets. He came up with the concept of lemma, which is a way of representing the epicyclical motion of planets without using Ptolemic method. Lemma was intended to replace the concept of equant as well.

Earth rotation

Abu Rayhan Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

(b. 973) discussed the possibility of whether the Earth rotated about its own axis and around the Sun, but in his ''Masudic Canon'', he set forth the principles that the Earth is at the center of the universe and that it has no motion of its own. He was aware that if the Earth rotated on its axis, this would be consistent with his astronomical parameters, but he considered this a problem of natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wo ...

rather than mathematics.

His contemporary, Abu Sa'id al-Sijzi, accepted that the Earth rotates around its axis. Al-Biruni described an astrolabe invented by Sijzi based on the idea that the earth rotates:

The fact that some people did believe that the earth is moving on its own axis is further confirmed by an Arabic reference work from the 13th century which states:According to the geometers r engineers(''muhandisīn''), the earth is in a constant circular motion, and what appears to be the motion of the heavens is actually due to the motion of the earth and not the stars.At the

Maragha

Maragheh ( fa, مراغه, Marāgheh or ''Marāgha''; az, ماراغا ) is a city and capital of Maragheh County, East Azerbaijan Province, Iran. Maragheh is on the bank of the river Sufi Chay. The population consists mostly of Iranian Azerba ...

and Samarkand observatories, the Earth's rotation was discussed by al-Kātibī (d. 1277), Tusi

''Tusi'', often translated as "headmen" or "chieftains", were hereditary tribal leaders recognized as imperial officials by the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties of China, and the Later Lê and Nguyễn dynasties of Vietnam. They ruled certain e ...

(b. 1201) and Qushji (b. 1403). The arguments and evidence used by Tusi and Qushji resemble those used by Copernicus to support the Earth's motion. However, it remains a fact that the Maragha school never made the big leap to heliocentrism.Toby E.Huff(1993):''The rise of early modern science: Islam, China, and the West/ref>

Alternative geocentric systems

In the 12th century, non-heliocentric alternatives to the Ptolemaic system were developed by some Islamic astronomers inal-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

, following a tradition established by Ibn Bajjah

Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Yaḥyà ibn aṣ-Ṣā’igh at-Tūjībī ibn Bājja ( ar, أبو بكر محمد بن يحيى بن الصائغ التجيبي بن باجة), best known by his Latinised name Avempace (; – 1138), was an A ...

, Ibn Tufail

Ibn Ṭufail (full Arabic name: ; Latinized form: ''Abubacer Aben Tofail''; Anglicized form: ''Abubekar'' or ''Abu Jaafar Ebn Tophail''; c. 1105 – 1185) was an Arab Andalusian Muslim polymath: a writer, Islamic philosopher, Islamic the ...

, and Ibn Rushd

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psychology, ...

.

A notable example is Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji, who considered the Ptolemaic model mathematical, and not physical. Al-Bitruji proposed a theory on planetary motion

In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such as a ...

in which he wished to avoid both epicycles and eccentrics. He was unsuccessful in replacing Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

's planetary model, as the numerical predictions of the planetary positions in his configuration were less accurate than those of the Ptolemaic model. One original aspects of al-Bitruji's system is his proposal of a physical cause of celestial motions. He contradicts the Aristotelian idea that there is a specific kind of dynamics for each world, applying instead the same dynamics to the sublunar and the celestial worlds.

Later period

In the late thirteenth century, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi created theTusi couple

The Tusi couple is a mathematical device in which a small circle rotates inside a larger circle twice the diameter of the smaller circle. Rotations of the circles cause a point on the circumference of the smaller circle to oscillate back and fo ...

, as pictured above. Other notable astronomers from the later medieval period include Mu'ayyad al-Din al-'Urdi

Al-Urdi (full name: Moayad Al-Din Al-Urdi Al-Amiri Al-Dimashqi) () (d. 1266) was a medieval Syrian Arab astronomer and geometer.

Born circa 1200, presumably (from the nisba ''al‐ʿUrḍī'') in the village of ''ʿUrḍ'' in the Syrian desert ...

(c. 1266), Qutb al-Din al Shirazi

Qotb al-Din Mahmoud b. Zia al-Din Mas'ud b. Mosleh Shirazi (1236–1311) ( fa, قطبالدین محمود بن ضیاالدین مسعود بن مصلح شیرازی) was a 13th-century Persian polymath and poet who made contributions to a ...

(c. 1311), Sadr al-Sharia al-Bukhari (c. 1347), Ibn al-Shatir

ʿAbu al-Ḥasan Alāʾ al‐Dīn ʿAlī ibn Ibrāhīm al-Ansari known as Ibn al-Shatir or Ibn ash-Shatir ( ar, ابن الشاطر; 1304–1375) was an Arab astronomer, mathematician and engineer. He worked as ''muwaqqit'' (موقت, religious t ...

(c. 1375), and Ali al-Qushji (c. 1474).

In the fifteenth century, the Timurid Timurid refers to those descended from Timur (Tamerlane), a 14th-century conqueror:

* Timurid dynasty, a dynasty of Turco-Mongol lineage descended from Timur who established empires in Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent

** Timurid Empire of C ...

ruler Ulugh Beg

Mīrzā Muhammad Tāraghay bin Shāhrukh ( chg, میرزا محمد طارق بن شاہ رخ, fa, میرزا محمد تراغای بن شاہ رخ), better known as Ulugh Beg () (22 March 1394 – 27 October 1449), was a Timurid sultan, as ...

of Samarkand established his court as a center of patronage for astronomy. He studied it in his youth, and in 1420 ordered the construction of Ulugh Beg Observatory

The Ulugh Beg Observatory is an observatory in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. Built in the 1420s by the Timurid astronomer Ulugh Beg. Islamic astronomers who worked at the observatory include Al-Kashi, Ali Qushji, and Ulugh Beg himself. The observat ...

, which produced a new set of astronomical tables, as well as contributing to other scientific and mathematical advances.

Several major astronomical works were produced in the early 16th century, including ones by 'Abd al-Ali al-Birjandi

Abd Ali ibn Muhammad ibn Husayn Birjandi ( fa, عبدعلی محمد بن حسین بیرجندی) (died 1528) was a prominent 16th-century Persian astronomer, mathematician and physicist who lived in Birjand.

Astronomy

Al-Birjandi was a pupil ...

(d. 1525 or 1526) and Shams al-Din al-Khafri

Shams al-Din Muhammad b. Ahmad al-Khafri al-Kashi (died 1550), known as Khafri, was an Iranian religious scholar and astronomer at the beginning of the Safavid dynasty. Before the arrival of Sheikh Baha'i in Iran, he was appointed as the major Sh ...

(fl. 1525). However, the vast majority of works written in this and later periods in the history of Islamic sciences are yet to be studied.

Influences

Europe

Several works of Islamic astronomy were translated to Latin starting from the 12th century.

The work of

Several works of Islamic astronomy were translated to Latin starting from the 12th century.

The work of al-Battani

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Jābir ibn Sinān al-Raqqī al-Ḥarrānī aṣ-Ṣābiʾ al-Battānī ( ar, محمد بن جابر بن سنان البتاني) ( Latinized as Albategnius, Albategni or Albatenius) (c. 858 – 929) was an astron ...

(d. 929), ''Kitāb az-Zīj'' ("Book of Astronomical Tables

In astronomy and celestial navigation, an ephemeris (pl. ephemerides; ) is a book with tables that gives the trajectory of naturally occurring astronomical objects as well as artificial satellites in the sky, i.e., the Position (vector), positio ...

"), was frequently cited by European astronomers and received several reprints, including one with annotations by Regiomontanus

Johannes Müller von Königsberg (6 June 1436 – 6 July 1476), better known as Regiomontanus (), was a mathematician, astrologer and astronomer of the German Renaissance, active in Vienna, Buda and Nuremberg. His contributions were instrument ...

. Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulated ...

, in his book that initiated the Copernican Revolution

The Copernican Revolution was the paradigm shift from the Ptolemaic model of the heavens, which described the cosmos as having Earth stationary at the center of the universe, to the heliocentric model with the Sun at the center of the Solar Sys ...

, the ''De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium

''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (English translation: ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'') is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Polish Renaissance. The book, ...

'', mentioned al-Battani no fewer than 23 times, and also mentions him in the ''Commentariolus

The ''Commentariolus'' (''Little Commentary'') is Nicolaus Copernicus's brief outline of an early version of his revolutionary heliocentric theory of the universe. After further long development of his theory, Copernicus published the mature vers ...

''. Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe; generally called Tycho (14 December 154624 October 1601) was a Danish astronomer, known for his comprehensive astronomical observations, generally considered to be the most accurate of his time. He was ...

, Riccioli, Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws o ...

, Galileo and others frequently cited him or his observations. His data is still used in geophysics.

Around 1190, Al-Bitruji

Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji () (also spelled Nur al-Din Ibn Ishaq al-Betrugi and Abu Ishâk ibn al-Bitrogi) (known in the West by the Latinized name of Alpetragius) (died c. 1204) was an Iberian-Arab astronomer and a Qadi in al-Andalus. Al-Biṭrūjī ...

published an alternative geocentric system to Ptolemy's model. His system spread through most of Europe during the 13th century, with debates and refutations of his ideas continued to the 16th century. In 1217, Michael Scot

Michael Scot (Latin: Michael Scotus; 1175 – ) was a Scottish mathematician and scholar in the Middle Ages. He was educated at Oxford and Paris, and worked in Bologna and Toledo, where he learned Arabic. His patron was Frederick II of the H ...

finished a Latin translation of al-Bitruji's ''Book of Cosmology'' (''Kitāb al-Hayʾah''), which became a valid alternative to Ptolemy's '' Almagest'' in scholastic circles. Several European writers, including Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus (c. 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop. Later canonised as a Catholic saint, he was known during his li ...

and Roger Bacon, explained it in detail and compared it with Ptolemy's. Copernicus cited his system in the ''De revolutionibus'' while discussing theories of the order of the inferior planets.

Some historians maintain that the thought of the Maragheh observatory

The Maragheh observatory (Persian: رصدخانه مراغه), also spelled Maragha, Maragah, Marageh, and Maraga, was an astronomical observatory established in the mid 13th century under the patronage of the Ilkhanid Hulagu and the directorship ...

, in particular the mathematical devices known as the Urdi lemma and the Tusi couple

The Tusi couple is a mathematical device in which a small circle rotates inside a larger circle twice the diameter of the smaller circle. Rotations of the circles cause a point on the circumference of the smaller circle to oscillate back and fo ...

, influenced Renaissance-era European astronomy and thus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulated ...

.

Copernicus used such devices in the same planetary models as found in Arabic sources.

Furthermore, the exact replacement of the equant

Equant (or punctum aequans) is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of the planets. The equant is used to explain the observed speed change in different stages of the plane ...

by two epicycles used by Copernicus in the ''Commentariolus

The ''Commentariolus'' (''Little Commentary'') is Nicolaus Copernicus's brief outline of an early version of his revolutionary heliocentric theory of the universe. After further long development of his theory, Copernicus published the mature vers ...

'' was found in an earlier work by Ibn al-Shatir

ʿAbu al-Ḥasan Alāʾ al‐Dīn ʿAlī ibn Ibrāhīm al-Ansari known as Ibn al-Shatir or Ibn ash-Shatir ( ar, ابن الشاطر; 1304–1375) was an Arab astronomer, mathematician and engineer. He worked as ''muwaqqit'' (موقت, religious t ...

(d. c. 1375) of Damascus. Copernicus' lunar and Mercury models are also identical to Ibn al-Shatir's.

While the influence of the criticism of Ptolemy by Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psy ...

on Renaissance thought is clear and explicit, the claim of direct influence of the Maragha school, postulated by Otto E. Neugebauer in 1957, remains an open question. Since the Tusi couple

The Tusi couple is a mathematical device in which a small circle rotates inside a larger circle twice the diameter of the smaller circle. Rotations of the circles cause a point on the circumference of the smaller circle to oscillate back and fo ...

was used by Copernicus in his reformulation of mathematical astronomy, there is a growing consensus that he became aware of this idea in some way. It has been suggested that the idea of the Tusi couple may have arrived in Europe leaving few manuscript traces, since it could have occurred without the translation of any Arabic text into Latin. One possible route of transmission may have been through Byzantine science

Byzantine science played an important role in the transmission of classical knowledge to the Islamic world and to Renaissance Italy, and also in the transmission of Islamic science to Renaissance Italy. Its rich historiographical tradition preser ...

, which translated some of al-Tusi Al-Tusi or Tusi is the title of several Iranian scholars who were born in the town of Tous in Khorasan. Some of the scholars with the al-Tusi title include:

* Abu Nasr as-Sarraj al-Tūsī (d. 988), Sufi sheikh and historian.

*Aḥmad al Ṭūsī ( ...

's works from Arabic into Byzantine Greek. Several Byzantine Greek manuscripts containing the Tusi-couple are still extant in Italy. Other scholars have argued that Copernicus could well have developed these ideas independently of the late Islamic tradition.Goddu (2010, pp. 261–69, 476–86), Huff (2010pp. 263–64)

di Bono (1995), Veselovsky (1973). Copernicus explicitly references several astronomers of the "

Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

" (10th to 12th centuries) in ''De Revolutionibus'': Albategnius (Al-Battani), Averroes (Ibn Rushd), Thebit (Thabit Ibn Qurra), Arzachel (Al-Zarqali), and Alpetragius (Al-Bitruji), but he does not show awareness of the existence of any of the later astronomers of the Maragha school.

It has been argued that Copernicus could have independently discovered the Tusi couple or took the idea from Proclus's ''Commentary on the First Book of Euclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the '' Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of ...

'', which Copernicus cited.

Another possible source for Copernicus's knowledge of this mathematical device is the ''Questiones de Spera'' of Nicole Oresme

Nicole Oresme (; c. 1320–1325 – 11 July 1382), also known as Nicolas Oresme, Nicholas Oresme, or Nicolas d'Oresme, was a French philosopher of the later Middle Ages. He wrote influential works on economics, mathematics, physics, astrology an ...

, who described how a reciprocating linear motion of a celestial body could be produced by a combination of circular motions similar to those proposed by al-Tusi.

China

Islamic influence on Chinese astronomy was first recorded during the

Islamic influence on Chinese astronomy was first recorded during the Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

when a Hui

The Hui people ( zh, c=, p=Huízú, w=Hui2-tsu2, Xiao'erjing: , dng, Хуэйзў, ) are an East Asian ethnoreligious group predominantly composed of Chinese-speaking adherents of Islam. They are distributed throughout China, mainly in the n ...

Muslim astronomer named Ma Yize introduced the concept of seven days in a week and made other contributions.

Islamic astronomers were brought to China in order to work on calendar making and astronomy during the Mongol Empire and the succeeding Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fift ...

. The Chinese scholar Yeh-lu Chu'tsai accompanied Genghis Khan to Persia in 1210 and studied their calendar for use in the Mongol Empire. Kublai Khan brought Iranians to Beijing Ancient Observatory, Beijing to construct an observatory and an institution for astronomical studies.Richard Bulliet, Pamela Crossley, Daniel Headrick, Steven Hirsch, Lyman Johnson, and David Northrup. ''The Earth and Its Peoples''. 3. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005.

Several Chinese astronomers worked at the Maragheh observatory

The Maragheh observatory (Persian: رصدخانه مراغه), also spelled Maragha, Maragah, Marageh, and Maraga, was an astronomical observatory established in the mid 13th century under the patronage of the Ilkhanid Hulagu and the directorship ...

, founded by Nasir al-Din al-Tusi in 1259 under the patronage of Hulagu Khan in Persia. One of these Chinese astronomers was Fu Mengchi, or Fu Mezhai. In 1267, the Persian astronomer Jamal ad-Din (astronomer), Jamal ad-Din, who previously worked at Maragha observatory, presented Kublai Khan with seven #Instruments, Persian astronomical instruments, including a terrestrial globe and an armillary sphere, as well as an astronomical almanac, which was later known in China as the ''Wannian Li'' ("Ten Thousand Year Calendar" or "Eternal Calendar"). He was known as "Zhamaluding" in China, where, in 1271, he was appointed by Khan as the first director of the Islamic observatory in Beijing, known as the Islamic Astronomical Bureau, which operated alongside the Chinese Astronomical Bureau for four centuries. Islamic astronomy gained a good reputation in China for its theory of planetary latitudes, which did not exist in Chinese astronomy at the time, and for its accurate prediction of eclipses.

Some of the astronomical instruments constructed by the famous Chinese astronomer Guo Shoujing shortly afterwards resemble the style of instrumentation built at Maragheh. In particular, the "simplified instrument" (''jianyi'') and the large gnomon at the Gaocheng Astronomical Observatory show traces of Islamic influence. While formulating the Chinese calendar, Shoushili calendar in 1281, Shoujing's work in spherical trigonometry may have also been partially influenced by Mathematics in medieval Islam, Islamic mathematics, which was largely accepted at Kublai's court.Ho, Peng Yoke. (2000). ''Li, Qi, and Shu: An Introduction to Science and Civilization in China'', p. 105. Mineola: Dover Publications. . These possible influences include a pseudo-geometrical method for converting between equatorial and Ecliptic coordinate system, ecliptic coordinates, the systematic use of decimals in the underlying parameters, and the application of cubic interpolation in the calculation of the irregularity in the planetary motions.

Hongwu Emperor (r. 1368–1398) of the Ming dynasty (1328–1398), in the first year of his reign (1368), conscripted Han and non-Han astrology specialists from the astronomical institutions in Beijing of the former Mongolian Yuan to Nanjing to become officials of the newly established national observatory.

That year, the Ming government summoned for the first time the astronomical officials to come south from the upper capital of Yuan. There were fourteen of them. In order to enhance accuracy in methods of observation and computation, Hongwu Emperor reinforced the adoption of parallel calendar systems, the Han Chinese, Han and the Hui

The Hui people ( zh, c=, p=Huízú, w=Hui2-tsu2, Xiao'erjing: , dng, Хуэйзў, ) are an East Asian ethnoreligious group predominantly composed of Chinese-speaking adherents of Islam. They are distributed throughout China, mainly in the n ...

. In the following years, the Ming Court appointed several Hui

The Hui people ( zh, c=, p=Huízú, w=Hui2-tsu2, Xiao'erjing: , dng, Хуэйзў, ) are an East Asian ethnoreligious group predominantly composed of Chinese-speaking adherents of Islam. They are distributed throughout China, mainly in the n ...

astrologers to hold high positions in the Imperial Observatory. They wrote many books on Islamic astronomy and also manufactured astronomical equipment based on the Islamic system.

The translation of two important works into Chinese was completed in 1383: Zij (1366) and al-Madkhal fi Sina'at Ahkam al-Nujum, ''Introduction to Astrology'' (1004).

In 1384, a Chinese astrolabe was made for observing stars based on the instructions for making multi-purposed Islamic equipment. In 1385, the apparatus was installed on a hill in northern Nanjing.

Around 1384, during the Ming dynasty, Hongwu Emperor ordered the Chinese language, Chinese translation and compilation of Zij, Islamic astronomical tables, a task that was carried out by the scholars Mashayihei, a Muslim astronomer, and Wu Bozong, a Chinese scholar-official. These tables came to be known as the ''Huihui Lifa'' (''Muslim System of Calendrical Astronomy''), which was published in China a number of times until the early 18th century, though the Qing dynasty had officially abandoned the tradition of Chinese-Islamic astronomy in 1659. The Muslim astronomer Yang Guangxian was known for his attacks on the Jesuit's astronomical sciences.

Korea

In the early Joseon dynasty, Joseon period, the Islamic calendar served as a basis for calendar reform being more accurate than the existing Chinese-based calendars. A Korean translation of the ''Huihui Lifa'', a text combining

In the early Joseon dynasty, Joseon period, the Islamic calendar served as a basis for calendar reform being more accurate than the existing Chinese-based calendars. A Korean translation of the ''Huihui Lifa'', a text combining Chinese astronomy

Astronomy in China has a long history stretching from the Shang dynasty, being refined over a period of more than 3,000 years. The ancient Chinese people have identified stars from 1300 BCE, as Chinese star names later categorized in the twe ...

with Islamic astronomy works of Jamal ad-Din (astronomer), Jamal ad-Din, was studied in Korea under the Joseon dynasty during the time of Sejong the Great, Sejong in the fifteenth century. The tradition of Chinese-Islamic astronomy survived

Observatories

The first systematic observations in Islam are reported to have taken place under the patronage of

The first systematic observations in Islam are reported to have taken place under the patronage of al-Mamun

Abu al-Abbas Abdallah ibn Harun al-Rashid ( ar, أبو العباس عبد الله بن هارون الرشيد, Abū al-ʿAbbās ʿAbd Allāh ibn Hārūn ar-Rashīd; 14 September 786 – 9 August 833), better known by his regnal name Al-Ma'mu ...

. Here, and in many other private observatories from Damascus to Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon. I ...

, meridian (geography), meridian degree measurement were performed (al-Ma'mun's arc measurement), solar parameters were established, and detailed observations of the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

, Moon, and planets were undertaken.

During the tenth century, the Buwayhid dynasty encouraged the undertaking of extensive works in astronomy; such as the construction of a large-scale instruments with which observations were made in the year 950. This is known through recordings made in the zij of astronomers such as Ibn al-Alam. The great astronomer Abd Al-Rahman Al Sufi was patronised by prince Adud o-dowleh, who systematically revised Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

's catalogue of stars. Sharaf al-Daula also established a similar observatory in Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon. I ...

. Reports by Ibn Yunus

Abu al-Hasan 'Ali ibn 'Abd al-Rahman ibn Ahmad ibn Yunus al-Sadafi al-Misri (Arabic: ابن يونس; c. 950 – 1009) was an important Egyptian astronomer and mathematician, whose works are noted for being ahead of their time, having been based ...

and al-Zarqall in Toledo, Spain, Toledo and Córdoba, Spain, Cordoba indicate the use of sophisticated instruments for their time.

It was Malik Shah I who established the first large observatory, probably in Isfahan (city), Isfahan. It was here where Omar Khayyám with many other collaborators constructed a zij and formulated the Iranian calendar, Persian Solar Calendar a.k.a. the ''jalali calendar''. A modern version of this calendar, the Solar Hijri calendar, is still in official use in Iran and Afghanistan today.

The most influential observatory was however founded by Hulegu Khan during the thirteenth century. Here, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi supervised its technical construction at Maragha. The facility contained resting quarters for Hulagu Khan, as well as a library and mosque. Some of the top astronomers of the day gathered there, and from their collaboration resulted important modifications to the Ptolemaic system

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, an ...

over a period of 50 years.

Ulugh Beg

Mīrzā Muhammad Tāraghay bin Shāhrukh ( chg, میرزا محمد طارق بن شاہ رخ, fa, میرزا محمد تراغای بن شاہ رخ), better known as Ulugh Beg () (22 March 1394 – 27 October 1449), was a Timurid sultan, as ...

, himself an astronomer and mathematician, founded another large observatory in Samarkand, the remains of which were excavated in 1908 by Russian teams.

And finally, Taqi al-Din Muhammad ibn Ma'ruf founded a Constantinople Observatory of Taqi ad-Din, large observatory in Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Constantinople in 1577, which was on the same scale as those in Maragha and Samarkand. The observatory was short-lived however, as opponents of the observatory and prognostication from the heavens prevailed and the observatory was destroyed in 1580.John Roberts (historian), John Morris Roberts, ''The History of the World'', pp. 264–74, Oxford University Press, While the Ottoman clergy did not object to the science of astronomy, the observatory was primarily being used for astrology, which they did oppose, and successfully sought its destruction.

As observatory development continued, Islamicate scientists began to pioneer the planetarium. The major difference between a planetarium and an observatory is how the universe is projected. In an observatory, you must look up into the night sky, on the other hand, planetariums allow for universes planets and stars to project at eye-level in a room. Scientist Ibn Firnas, created a planetarium in his home that included artificial storm noises and was completely made of glass. Being the first of its kind, it very similar to what we see for planetariums today.

Instruments

Our knowledge of the instruments used by Muslim astronomers primarily comes from two sources: first the remaining instruments in private and museum collections today, and second the treatises and manuscripts preserved from the Middle Ages. Muslim astronomers of the "Golden Period" made many improvements to instruments already in use before their time, such as adding new scales or details.Celestial globes and armillary spheres

Celestial globes were used primarily for solving problems in celestial astronomy. Today, 126 such instruments remain worldwide, the oldest from the 11th century. The altitude of the Sun, or the Right Ascension and Declination of stars could be calculated with these by inputting the location of the observer on the meridian ring of the globe. The initial blueprint for a portable celestial globe to measure celestial coordinates came from Spanish Muslim astronomer Jabir ibn Aflah (d. 1145). Another skillful Muslim astronomer working on celestial globes was Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi (b. 903), whose treatise the ''Book of Fixed Stars'' describes how to design the constellation images on the globe, as well as how to use the celestial globe. However, it was in Iraq in the 10th century that astronomer Al-Battani was working on celestial globes to record celestial data. This was different because up until then, the traditional use for a celestial globe was as an observational instrument. Al-Battani's treatise describes in detail the plotting coordinates for 1,022 stars, as well as how the stars should be marked. An armillary sphere had similar applications. No early Islamic armillary spheres survive, but several treatises on "the instrument with the rings" were written. In this context there is also an Islamic development, the spherical astrolabe, of which only one complete instrument, from the 14th century, has survived.

Celestial globes were used primarily for solving problems in celestial astronomy. Today, 126 such instruments remain worldwide, the oldest from the 11th century. The altitude of the Sun, or the Right Ascension and Declination of stars could be calculated with these by inputting the location of the observer on the meridian ring of the globe. The initial blueprint for a portable celestial globe to measure celestial coordinates came from Spanish Muslim astronomer Jabir ibn Aflah (d. 1145). Another skillful Muslim astronomer working on celestial globes was Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi (b. 903), whose treatise the ''Book of Fixed Stars'' describes how to design the constellation images on the globe, as well as how to use the celestial globe. However, it was in Iraq in the 10th century that astronomer Al-Battani was working on celestial globes to record celestial data. This was different because up until then, the traditional use for a celestial globe was as an observational instrument. Al-Battani's treatise describes in detail the plotting coordinates for 1,022 stars, as well as how the stars should be marked. An armillary sphere had similar applications. No early Islamic armillary spheres survive, but several treatises on "the instrument with the rings" were written. In this context there is also an Islamic development, the spherical astrolabe, of which only one complete instrument, from the 14th century, has survived.

Astrolabes

Brass astrolabes were an invention of Late Antiquity. The first Islamic astronomer reported as having built an astrolabe is Muḥammad ibn Ibrāhīm al-Fazārī, Muhammad al-Fazari (late 8th century). Astrolabes were popular in the Islamic world during the "Golden Age", chiefly as an aid to finding theqibla

The qibla ( ar, قِبْلَة, links=no, lit=direction, translit=qiblah) is the direction towards the Kaaba in the Sacred Mosque in Mecca, which is used by Muslims in various religious contexts, particularly the direction of prayer for the ...

. The earliest known example is dated to 927/8 (AH 315).

The device was incredibly useful, and sometime during the 10th century it was brought to Europe from the Muslim world, where it inspired Latin scholars to take up a vested interest in both math and astronomy. Despite how much we know much about the tool, many of the functions of the device have become lost to history. Although it is true that there are many surviving instruction manuals, historians have come to the conclusion that there are more functions of specialized astrolabes that we do not know of. One example of this is an astrolabe created by Nasir al-Din al-Tusi in Aleppo in the year 1328/29 C.E. This particular astrolabe was special and is hailed by historians as the "most sophisticated astrolabe ever made", being known to have five distinct universal uses.

The largest function of the astrolabe is it serves as a portable model of space that can calculate the approximate location of any heavenly body found within the solar system at any point in time, provided the latitude of the observer is accounted for. In order to adjust for latitude, astrolabes often had a second plate on top of the first, which the user could swap out to account for their correct latitude. One of the most useful features of the device is that the projection created allows users to calculate and solve mathematical problems graphically which could otherwise be done only by using complex spherical trigonometry, allowing for earlier access to great mathematical feats. In addition to this, use of the astrolabe allowed for ships at sea to calculate their position given that the device is fixed upon a star with a known altitude. Standard astrolabes performed poorly on the ocean, as bumpy waters and aggressive winds made use difficult, so a new iteration of the device, known as a Mariner's astrolabe, was developed to counteract the difficult conditions of the sea.

The instruments were used to read the time of the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

rising and fixed stars. al-Zarqali of Andalusia constructed one such instrument in which, unlike its predecessors, did not depend on the latitude of the observer, and could be used anywhere. This instrument became known in Europe as the Saphea.

The astrolabe was arguably the most important instrument created and used for astronomical purposes in the medieval period. Its invention in early medieval times required immense study and much trial and error in order to find the right method of which to construct it to where it would work efficiently and consistently, and its invention led to several mathematic advances which came from the problems that arose from using the instrument. The astrolabe's original purpose was to allow one to find the altitudes of the sun and many visible stars, during the day and night, respectively. However, they have ultimately come to provide great contribution to the progress of mapping the globe, thus resulting in further exploration of the sea, which then resulted in a series of positive events that allowed the world we know today to come to be. The astrolabe has served many purposes over time, and it has shown to be quite a key factor from medieval times to the present.

The astrolabe, as mentioned before, required the use of mathematics, and the development of the instrument incorporated azimuth circles, which opened a series of questions on further mathematical dilemmas. Astrolabes served the purpose of finding the altitude of the sun, which also meant that they provided one the ability to find the direction of Muslim prayer (or the direction of Mecca). Aside from these perhaps more widely known purposes, the astrolabe has led to many other advances as well. One very important advance to note is the great influence it had on navigation, specifically in the marine world. This advancement is incredibly important because the calculation of latitude being made more simple not only allowed for the increase in sea exploration, but it eventually led to the Renaissance revolution, the increase in global trade activity, even the discovery of several of the world's continents.