Arab Higher Committee on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Arab Higher Committee ( ar, اللجنة العربية العليا) or the Higher National Committee was the central political organ of the Arab Palestinians in

The first Arab Higher Committee was formed on 25 April 1936, following the outbreak of the

The first Arab Higher Committee was formed on 25 April 1936, following the outbreak of the

, Palestine under the Mandate, 3 September 1947 The commission reported in July 1937 and recommended the partition of Palestine into Jewish and Arab states. Arab leaders, both in the Husseini-controlled Arab Higher Committee and in the Nashashibi National Defense Party denounced partition and reiterated their demands for independence,Pappé Ilan (2004) ''A History of Modern Palestine: One Land, Two Peoples'', Cambridge University Press, arguing that the Arabs had been promised independence and granting rights to the Jews was a betrayal. The Arabs emphatically rejected the principle of awarding any territory to the Jews. After British rejection of an Arab Higher Committee petition to hold an Arab conference in Jerusalem, hundreds of delegates from across the Arab world convened at the Bloudan Conference in Syria on 8 September 1937, including 97 Palestinian delegates. The conference rejected both the partition and establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. After the rejection of the Peel proposals, the revolt resumed. Members of the On 26 September 1937, the acting British district commissioner of Galilee,

On 26 September 1937, the acting British district commissioner of Galilee,

When the committee was outlawed in September 1937, six of its members were deported, its president Amin al-Husayni managed to escape arrest and went into exile in

When the committee was outlawed in September 1937, six of its members were deported, its president Amin al-Husayni managed to escape arrest and went into exile in

PART II, 1947–1977

,

Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 ...

. It was established on 25 April 1936, on the initiative of Haj Amin al-Husayni

Mohammed Amin al-Husseini ( ar, محمد أمين الحسيني 1897

– 4 July 1974) was a Palestinian Arab nationalist and Muslim leader in Mandatory Palestine.

Al-Husseini was the scion of the al-Husayni family of Jerusalemite Arab notable ...

, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem

The Grand Mufti of Jerusalem is the Sunni Muslim cleric in charge of Jerusalem's Islamic holy places, including the Al-Aqsa Mosque. The position was created by the British military government led by Ronald Storrs in 1918.See Islamic Leadershi ...

, and comprised the leaders of Palestinian Arab clans and political parties under the mufti's chairmanship. The committee was outlawed by the British Mandatory administration in September 1937 after the assassination of a British official.

A committee of the same name was reconstituted by the Arab League in 1945, but went to abeyance after it proved ineffective during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. It was sidestepped by Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

and the Arab League with the formation of the All-Palestine Government

, image =

, caption = Flag of the All-Palestine Government

, date = 22 September 1948

, state = All-Palestine Protectorate

, address = Gaza City, All-Palestine Protectorate (Sep.–Dec. 19 ...

in 1948 and both were banned by Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

.

Formation, 1936–37

The first Arab Higher Committee was formed on 25 April 1936, following the outbreak of the

The first Arab Higher Committee was formed on 25 April 1936, following the outbreak of the Great Arab revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية الكبرى, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On t ...

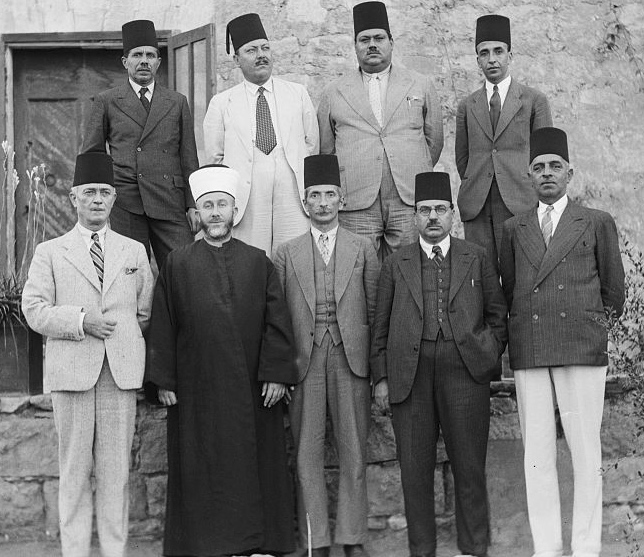

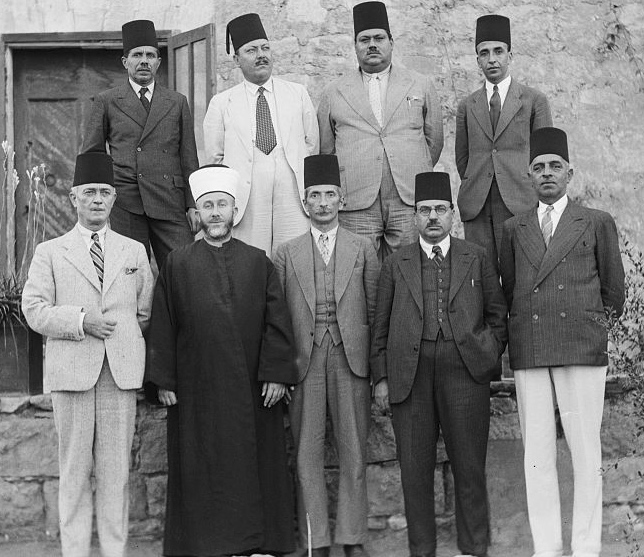

, and national committees were formed in all of the towns and some of the larger villages, during that month.Peel Commission Report Cmd. 5479, 1937, p. 96. The members of the committee were:

* Amin al-Husayni

Mohammed Amin al-Husseini ( ar, محمد أمين الحسيني 1897

– 4 July 1974) was a Palestinian Arab nationalist and Muslim leader in Mandatory Palestine.

Al-Husseini was the scion of the al-Husayni family of Jerusalemite Arab notab ...

, president – member of the al-Husayni

Husayni ( ar, الحسيني also spelled Husseini) is the name of a prominent Palestinian Arab clan formerly based in Jerusalem, which claims descent from Husayn ibn Ali (the son of Ali).

The Husaynis follow the Hanafi school of Sunni Islam ...

clan, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem

The Grand Mufti of Jerusalem is the Sunni Muslim cleric in charge of Jerusalem's Islamic holy places, including the Al-Aqsa Mosque. The position was created by the British military government led by Ronald Storrs in 1918.See Islamic Leadershi ...

, and president of the Supreme Muslim Council

The Supreme Muslim Council (SMC; ar, المجلس الإسلامي الاعلى) was the highest body in charge of Muslim community affairs in Mandatory Palestine under British control. It was established to create an advisory body composed of ...

until his dismissal from that position

* Raghib al-Nashashibi

Raghib al-Nashashibi ( ar, راغب النشاشيبي, ) (1881–1951), CBE (hon), was a wealthy landowner and public figure during the Ottoman Empire, the British Mandate and the Jordanian administration. He was a member of the Nashashibi clan ...

– member of the Nashashibi

Nashashibi ( ar, النشاشيبي; transliteration, Al-Nashāshībī) is the name of a prominent Palestinian family based in Jerusalem.

After the First World War, during the British period, Raghib al-Nashashibi was Mayor of Jerusalem (1920–1 ...

clan, which was considered to be political rivals of the al-Husayni

Husayni ( ar, الحسيني also spelled Husseini) is the name of a prominent Palestinian Arab clan formerly based in Jerusalem, which claims descent from Husayn ibn Ali (the son of Ali).

The Husaynis follow the Hanafi school of Sunni Islam ...

clan, and to hold moderate views when compared to the more militant views of the al-Husayni, member of the National Defence Party

* Jamal al-Husayni

Jamal al-Husayni (1894-1982) ( ar, جمال الحُسيني), was born in Jerusalem and was a member of the highly influential and respected Husayni family.

Husayni served as Secretary to the Executive Committee of the Palestine Arab Congress ...

– related to Amin al-Husayni and chairman of the Palestine Arab Party

The Palestinian Arab Party ( ar, الحزب العربي الفلسطيني ''‘Al-Hizb al-'Arabi al-Filastini'') was a political party in Palestine established by the influential Husayni family in May 1935. Jamal al-Husayni was the founder and ...

, member of the Supreme Muslim Council

* Yaqub al-Ghusayn

Yaqub al-Ghussein ( ar, يعقوب الغصين, ) (1899-1948) was a Palestinian landowner from Ramla and founder of the Youth Congress Party. He graduated in law from the University of Cambridge. Ghussein was elected president of the first Natio ...

– member and representative of the Youth Congress Party

The Youth Congress Party was a Palestinian political party that was established by Yaqub al-Ghusayn. It was formed in 1932 in the British Mandate of Palestine and quickly grew to become the largest nationalist association of the early 1930s, counti ...

, member of the Supreme Muslim Council, deported

* – founder of the National Bloc

* Husayin al-Khalidi

Husayn Fakhri al-Khalidi ( ar, حسين فخري الخالدي, , 1895 – 6 February 1962) was mayor of Jerusalem from 1934 to 1937 and the 13th Prime Minister of Jordan in 1957.

On 23 June 1935 Khalidi founded the Reform Party and was subsequ ...

– founder and representative of the Reform Party, deported

* Awni Abd al-Hadi

Awni Abd al-Hadi, ( ar, عوني عبد الهادي) aka Auni Bey Abdel Hadi (1889, Nablus, Ottoman Empire – 15 March 1970, Cairo, Egypt) was a Palestinian political figure. He was educated in Beirut, Istanbul, and at the Sorbonne University ...

– leader of the Istiqlal (Independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

) Party, who was appointed General Secretary

* Ahmed Hilmi Pasha

Ahmed Hilmi Abd al-Baqi ( ar, أحمد حلمي عبد الباقي 1883 - 1963) was a soldier, economist, and politician, who served in various post-Ottoman Empire governments, and was Prime Minister of the short-lived All-Palestine Government ...

– treasurer, deported.

Initially, the committee included representatives of the rival Nashashibi

Nashashibi ( ar, النشاشيبي; transliteration, Al-Nashāshībī) is the name of a prominent Palestinian family based in Jerusalem.

After the First World War, during the British period, Raghib al-Nashashibi was Mayor of Jerusalem (1920–1 ...

and al-Husayni

Husayni ( ar, الحسيني also spelled Husseini) is the name of a prominent Palestinian Arab clan formerly based in Jerusalem, which claims descent from Husayn ibn Ali (the son of Ali).

The Husaynis follow the Hanafi school of Sunni Islam ...

clans. The committee was formed after the 19 April call for a general strike of Arab workers and businesses, which marked the start of the 1936–39 Arab revolt. On 15 May 1936, the committee endorsed the general strike, calling for an end to Jewish immigration; the prohibition of the transfer of Arab land to Jews; and the establishment of a National Government responsible to a representative council. Later it called for the nonpayment of taxes. Raghib al-Nashashibi

Raghib al-Nashashibi ( ar, راغب النشاشيبي, ) (1881–1951), CBE (hon), was a wealthy landowner and public figure during the Ottoman Empire, the British Mandate and the Jordanian administration. He was a member of the Nashashibi clan ...

, of the Nashashibi

Nashashibi ( ar, النشاشيبي; transliteration, Al-Nashāshībī) is the name of a prominent Palestinian family based in Jerusalem.

After the First World War, during the British period, Raghib al-Nashashibi was Mayor of Jerusalem (1920–1 ...

clan and member of the National Defence Party soon withdrew from the committee.

In November 1936, and with the prospects of war in Europe increasing, the British government set up the Peel Royal Commission to investigate the causes of the disturbances. The strike had been called off in October 1936 and the violence abated for about a year while the Peel Commission deliberated. The commission was impressed by the fact that the Arab national movement, sustained by the committee, was a far more efficient and comprehensive political machine than had existed in earlier years. All the political parties presented a 'common front' and their leaders sit together on the Arab Higher Committee. Christian as well as Muslim Arabs were represented on it, with no opposition parties.UN special committee, Palestine under the Mandate, 3 September 1947 The commission reported in July 1937 and recommended the partition of Palestine into Jewish and Arab states. Arab leaders, both in the Husseini-controlled Arab Higher Committee and in the Nashashibi National Defense Party denounced partition and reiterated their demands for independence,Pappé Ilan (2004) ''A History of Modern Palestine: One Land, Two Peoples'', Cambridge University Press, arguing that the Arabs had been promised independence and granting rights to the Jews was a betrayal. The Arabs emphatically rejected the principle of awarding any territory to the Jews. After British rejection of an Arab Higher Committee petition to hold an Arab conference in Jerusalem, hundreds of delegates from across the Arab world convened at the Bloudan Conference in Syria on 8 September 1937, including 97 Palestinian delegates. The conference rejected both the partition and establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. After the rejection of the Peel proposals, the revolt resumed. Members of the

Nashashibi

Nashashibi ( ar, النشاشيبي; transliteration, Al-Nashāshībī) is the name of a prominent Palestinian family based in Jerusalem.

After the First World War, during the British period, Raghib al-Nashashibi was Mayor of Jerusalem (1920–1 ...

family began to be targeted, as well as the Jewish community and British administrators. Raghib Nashashibi was forced to flee to Egypt after several assassination attempts on him, which were ordered by Amin al-Husayni.

On 26 September 1937, the acting British district commissioner of Galilee,

On 26 September 1937, the acting British district commissioner of Galilee, Lewis Yelland Andrews

Lewis Yelland Andrews (26 September 1896-26 September 1937) was an Australian soldier and colonial official who served as the acting District Commissioner for the region of Galilee during the British Mandate over Palestine. He was assassinated ...

, was assassinated in Nazareth. Four days later Britain outlawed the Arab Higher Committee, and began to arrest its members. On 1 October 1937, the National Bloc, the Reform Party and the Istiqlal Party were dissolved.''A Survey of Palestine – prepared in December 1945 and January 1946 for the information of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry.'' Reprinted 1991 by The Institute of Palestine Studies, Washington. Volume II. . p.949 Yaqub al-Ghusayn, Al-Khalidi and Ahmed Hilmi Pasha were arrested and then deported. Jamal al-Husayni escaped to Syria, as did Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni. Amin al-Husayni managed to escape arrest, but was removed from the presidency of the Supreme Muslim Council. The committee was banned by the Mandate administration and three members (and two other Palestinian leaders) were deported to the Seychelles

Seychelles (, ; ), officially the Republic of Seychelles (french: link=no, République des Seychelles; Creole: ''La Repiblik Sesel''), is an archipelagic state consisting of 115 islands in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city, ...

and the others moved into voluntary exile in neighbouring countries. Awni Abd al-Hadi, who was out of the country at the time, was not allowed to return. The National Defence Party, which had withdrawn from the AHC soon after its formation, was not outlawed, and Raghib al-Nashashibi was not pursued by the British.

War period, 1938–1945

When the committee was outlawed in September 1937, six of its members were deported, its president Amin al-Husayni managed to escape arrest and went into exile in

When the committee was outlawed in September 1937, six of its members were deported, its president Amin al-Husayni managed to escape arrest and went into exile in Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

. Jamal al-Husayni escaped to Syria. Three other members were deported to the Seychelles, and other members moved into voluntary exile in neighbouring countries. Al-Hadi, who was out of the country at the time, was not allowed to return. Membership of the outlawed committee had dwindled to Jamal al-Husayni (acting chairperson), Husayn al-Khalidi (secretary), Ahmed Hilmi Pasha

Ahmed Hilmi Abd al-Baqi ( ar, أحمد حلمي عبد الباقي 1883 - 1963) was a soldier, economist, and politician, who served in various post-Ottoman Empire governments, and was Prime Minister of the short-lived All-Palestine Government ...

and Emil Ghuri

Emil Ghuri ( ar, إميل الغوري, alternatively spelled Emil Ghoury) (1907–1984), a Palestinian Christian who was Secretary-General of the Arab Higher Committee (AHC), the official leadership of the Arabs in British Mandate of Palestine ...

. For all practical purposes, the committee ceased to exist, however, this brought little change in the structure of Arab political life and the Palestinian revolt continued.

With the indications of a new European war on the horizon, and in an endeavor to resolve the inter-communal issues in Palestine, the British government proposed in late 1938 a conference in London of the two Palestinian communities. Some Arab leaders welcomed the proposed London Conference but indicated that the British would need to deal with the disbanded Arab Higher Committee and with Amin al-Husayni. On 23 November 1938, the Colonial Secretary, Malcolm MacDonald

Malcolm Ian Macdonald (born 7 January 1950) is an English former professional footballer, manager and media figure. Nicknamed 'Supermac', Macdonald was a quick, powerfully built prolific goalscorer. He played for Fulham, Luton Town, Newcastle ...

, repeated his refusal to allow Amin al-Husayni to be a delegate, but was willing to allow the five Palestinian leaders held in the Seychelles to take part in the conference. The deportees were released on 19 December and allowed to travel to Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the Capital city, capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, List of ...

and then, with Jamal Husseini, to Beirut where a new Arab Higher Committee (or Higher National Committee) was established. Amin al-Husayni was not a member of the Arab delegation but the delegation was clearly acting under his direction. The London Conference commenced on 7 February 1939, but the Arab delegation refused to sit in the same room with the Jewish delegation present, and the conference broke up in March with no success. In May 1939, the British government presented its 1939 White Paper

The White Paper of 1939Occasionally also known as the MacDonald White Paper (e.g. Caplan, 2015, p.117) after Malcolm MacDonald, the British Colonial Secretary, who presided over its creation. was a policy paper issued by the British government ...

which was rejected by both sides. The White Paper had, in effect, repudiated the Balfour Declaration. According to Benny Morris, Amin al-Husayni "astonished" the other members of the Arab Higher Committee by turning down the ''White Paper''. Al-Husayni turned the advantageous proposal down because "it did not place him at the helm of the future Palestinian state."

The deportees were not allowed to return to Palestine until 1941. Amin Al-Husayni spent the war years in occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 an ...

, actively collaborating with the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

leadership. Amin and Jamal al-Husayni were involved in the 1941 pro-Nazi Rashidi revolt in Iraq. Amin again evaded capture by Britain but Jamal was captured in 1941 and interned in Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a landlocked self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally kno ...

, where he was held until November 1945 when he was allowed to move to Cairo. Husayn al-Khalidi returned to Palestine in 1943. Jamal al-Husayni returned to British Palestine in February 1946 as an official of the new Arab Higher Committee, by then recognised by the Mandate administration. Amin Al-Husayni never returned to British Palestine.

Reconstituted committee, 1945–1948

1945–46

After the end of the war, Amin al-Husayni managed to find his way toEgypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

and stayed there until 1959, when he moved to Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

. On 22 March 1945, the Arab League was formed.

In November 1945, on the urging of Egypt, its leading member, the then seven members of the Arab League (Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Yemen) reconstituted the Arab Higher Committee comprising twelve members as the supreme executive body of Palestinian Arabs in the territory of the British Mandate of Palestine British Mandate of Palestine or Palestine Mandate most often refers to:

* Mandate for Palestine: a League of Nations mandate under which the British controlled an area which included Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan.

* Mandatory P ...

. The committee was dominated by the Palestine Arab Party

The Palestinian Arab Party ( ar, الحزب العربي الفلسطيني ''‘Al-Hizb al-'Arabi al-Filastini'') was a political party in Palestine established by the influential Husayni family in May 1935. Jamal al-Husayni was the founder and ...

, controlled by the Husayni family, and was immediately recognised by Arab League countries. The Mandate government recognised the new committee two months later. In February 1946, Jamal al-Husayni returned from exile to Palestine and immediately set about reorganising and enlarging the committee, becoming its acting president. The members of the reconstituted committee as at April 1946 were:

*Jamal al-Husayni

Jamal al-Husayni (1894-1982) ( ar, جمال الحُسيني), was born in Jerusalem and was a member of the highly influential and respected Husayni family.

Husayni served as Secretary to the Executive Committee of the Palestine Arab Congress ...

* Tewfiq al-Husayni

* Yusif Sahyun

* Kamil al-Dajani

* Emile al-Ghury

*Rafiq al-Tamimi

Muhammad Rafiq al-Tamimi ( ar, محمد رفيق التميمي, 1889–1957) was a Palestinian Arab educator and political figure in the 20th century. He was appointed to the Arab Higher Committee in 1945 and was the chairman of the Palestinian Ar ...

and

* Anwar al-Khatib (all members of or affiliated with the Palestine Arab Party

The Palestinian Arab Party ( ar, الحزب العربي الفلسطيني ''‘Al-Hizb al-'Arabi al-Filastini'') was a political party in Palestine established by the influential Husayni family in May 1935. Jamal al-Husayni was the founder and ...

)

* Izzat Tannus (an independent Christian medical doctor)

* Antone Attallah (a member of the Greek Orthodox

The term Greek Orthodox Church ( Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also cal ...

community)

* Ahmad al-Shukayri (a lawyer from Acre and an Arab nationalist)

* Sami Taha – head of Palestine Arab Workers Society

The Palestine Arab Workers' Society (PAWS - ''Jam'iyyat al-'Ummal al-'Arabiyya al-Filastiniyya''), established in 1925, was the main Arab labor organization in the British Mandate of Palestine, with its headquarters in Haifa.

The Palestine Arab ...

* Yusif Haykal (the mayor of Jaffa, who was politically independent)

The Istiqlal Party

The Istiqlal Party ( ar, حزب الإستقلال, translit=Ḥizb Al-Istiqlāl, lit=Independence Party; french: Parti Istiqlal; zgh, ⴰⴽⴰⴱⴰⵔ ⵏ ⵍⵉⵙⵜⵉⵇⵍⴰⵍ) is a political party in Morocco. It is a conservative and ...

and other nationalist groups objected to these moves, and formed a rival Arab Higher Front.

In May 1946, the Arab League ordered the dissolution of the AHC and Arab Higher Front and formed a five-member Arab Higher Executive, under Amin al-Husayni's chairmanship, and based in Cairo. The new AHE consisted of:

*Amin al-Husayni

Mohammed Amin al-Husseini ( ar, محمد أمين الحسيني 1897

– 4 July 1974) was a Palestinian Arab nationalist and Muslim leader in Mandatory Palestine.

Al-Husseini was the scion of the al-Husayni family of Jerusalemite Arab notab ...

, as chairman

*Jamal al-Husayni

Jamal al-Husayni (1894-1982) ( ar, جمال الحُسيني), was born in Jerusalem and was a member of the highly influential and respected Husayni family.

Husayni served as Secretary to the Executive Committee of the Palestine Arab Congress ...

, as vice-chairman

*Husayin al-Khalidi

Husayn Fakhri al-Khalidi ( ar, حسين فخري الخالدي, , 1895 – 6 February 1962) was mayor of Jerusalem from 1934 to 1937 and the 13th Prime Minister of Jordan in 1957.

On 23 June 1935 Khalidi founded the Reform Party and was subsequ ...

* Emile al-Ghury

* Ahmed Hilmi Abd al-Baqi

The United Kingdom government called the 1946–47 London Conference on Palestine in an attempt to bring peace to its Mandate territory, which began on 9 September 1946. The conference was boycotted by the AHE as well as the Jewish Agency, but was attending by Arab League states, which argued against any partition.

1947–48

In January 1947, the AHE was renamed the "Arab Higher Committee", with Amin al-Husayni as its chairman and Jamal al-Husayni as vice-chairman, and expanded to include the four remaining core members plus Hasan Abu Sa'ud, Izhak Darwish al-Husayni, Izzat Darwaza,Rafiq al-Tamimi

Muhammad Rafiq al-Tamimi ( ar, محمد رفيق التميمي, 1889–1957) was a Palestinian Arab educator and political figure in the 20th century. He was appointed to the Arab Higher Committee in 1945 and was the chairman of the Palestinian Ar ...

and Mu'in al-Madi. This restructuring of the AHC to include additional supporters of Amin al-Husayni was seen as a bid to increase his political power.

Following the failure of the London Conference, the British referred the question to the UN on 14 February 1947.

In April 1947, the Arab Higher Committee repeated Arab and Palestinian demands in the solution for the Question of Palestine:

# A complete cessation of the Jewish migration to Palestine.

# A total halt to the sale of land to Jews.

# Cancelation of the British Mandate in Palestine and the Balfour Declaration.

# Recognition of the right of Arabs to their land and recognition of the independence of Palestine as a sovereign state, like all other Arab states, with a promise to provide minority rights to the Jews according to the rules of democracy.

The Arab states and the Arab Higher Committee officially boycotted the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine

The United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) was created on 15 May 1947 in response to a United Kingdom government request that the General Assembly "make recommendations under article 10 of the Charter, concerning the future govern ...

(UNSCOP) formed in May 1947 to investigate the cause of the conflict in Palestine, and, if possible, devise a solution. Despite the official Arab boycott, several Arab officials and intellectuals privately met UNSCOP members to argue for a unitary Arab-majority state, among them AHC member and former Jerusalem mayor Husayn al-Khalidi.Morris, Benny: 1948: ''A History of the First Arab-Israeli War'' UNSCOP also received written arguments from Arab advocates. The Arab Higher Committee rejected both the majority and minority recommendations within the UNSCOP report. They "concluded from a survey of Palestine history that Zionist claims to that country had no legal or moral basis". The Arab Higher Committee argued that only an Arab State in the whole of Palestine would be consistent with the UN Charter.

The Arab Higher Committee as well as the Arab states were actively involved in the deliberations of the Ad Hoc Committee on the Palestinian Question

The Ad Hoc Committee on the Palestinian Question, also known as the Ad Hoc Committee on Palestine or just the Ad Hoc Committee was a committee formed by a vote of the United Nations General Assembly on 23 September 1947, following the publication o ...

, formed in October 1947, again repeating its previous demands. Despite Arab objections, the ad hoc committee reported on 19 November 1947 in favour of a partition of Palestine.

The United Nations General Assembly voted on 29 November 1947 in favour of the Partition Plan for Palestine, all the Arab League states voting against the Plan. The Arab Higher Committee rejected the vote, declaring it invalid because it was opposed by Palestine's Arab majority.''The Origins and Evolution of the Palestine Problem

''The Origins and Evolution of the Palestine Problem'' is a study prepared by the United Nations Division for Palestinian Rights under the guidance of the Committee on the Exercise of the Inalienable Rights of the Palestinian People, as proposed on ...

''PART II, 1947–1977

,

United Nations Information System on the Question of Palestine The United Nations Information System on the Question of Palestine (UNISPAL) is an online collection of texts of current and historical United Nations decisions and publications concerning the question of Palestine, the Israeli–Palestinian confl ...

(UNISPAL), June 20, 1990, ST/SG/SER.F/1 The AHC also declared a three-day strike and public protest to begin on 2 December 1947, in protest at the vote. The call led to the 1947 Jerusalem riots

The 1947 Jerusalem Riots occurred following the vote in the UN General Assembly in favour of the 1947 UN Partition Plan on 29 November 1947.

The Arab Higher Committee declared a three-day strike and public protest to begin on 2 December 1947, i ...

between 2–5 December 1947, resulting in many deaths and much property damage.

On 12 April 1948, with the end of the mandate looming, the Arab League announced its intention to take over the whole of the British Mandate territory, with the objective being:

The Arab armies shall enter Palestine to rescue it. His Majesty (King Farouk, representing the League) would like to make it clearly understood that such measures should be looked upon as temporary and devoid of any character of the occupation or partition of Palestine, and that after completion of its liberation, that country would be handed over to its owners to rule in the way they like.The British Mandate of Palestine came to an end on 15 May 1948, on which day six of the then-seven Arab League states (Yemen being not active) invaded the now-former Mandate territory, marking the start of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. The Arab Higher Committee claimed that the British withdrawal led to an absence of legal authority, making it necessary for the Arab states to protect Arab lives and property. The Arab states' proclaimed their aim of a "United State of Palestine" in place of Israel and an Arab state. The Arab Higher Committee said that in the future Palestine, the Jews will be no more than 1/7 of the population. i.e. only Jews that lived in Palestine before the British mandate would be permitted to stay. They did not specify what would happen to the other Jews.

Criticism

The Arab Higher Committee has been criticised for not preparing the Palestinian population for the war, accepting the general expectation that Palestinian Arabs alone would not prevail over theYishuv

Yishuv ( he, ישוב, literally "settlement"), Ha-Yishuv ( he, הישוב, ''the Yishuv''), or Ha-Yishuv Ha-Ivri ( he, הישוב העברי, ''the Hebrew Yishuv''), is the body of Jewish residents in the Land of Israel (corresponding to the ...

, and accepting the joint Arab strategy of outside Arab armies securing a prompt takeover of the country.

Anwar Nusseibeh

Anwar Bey Nuseibeh ( ar, أنور نسيبة) Anwar Bey Nuseibeh (1913–1986) was a leading Palestinian who held several major posts in the Jordanian Government before Israel took control of East Jerusalem and the West Bank in the 1967 war. A ...

, a Palestinian nationalist who believed that the best way to advance Palestinian interest was to operate within whichever regime was in power, criticized the Arab Higher Committee's performance during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War as being unaware and ineffective at best and ambivalent at worst to the needs of the Palestinian Arab population. In a personal note, Nusseibeh wrote, "Obviously they thought of the Palestine adventure in terms of an easy walkover for the Arabs, and the only point that seemed to worry them was credit for the expected victory. ... hey

Hey or Hey! may refer to:

Music

* Hey (band), a Polish rock band

Albums

* ''Hey'' (Andreas Bourani album) or the title song (see below), 2014

* ''Hey!'' (Julio Iglesias album) or the title song, 1980

* ''Hey!'' (Jullie album) or the title s ...

were determined that the Palestine Arabs should at all costs be excluded."

The Arab community, being essentially agrarian, is loosely knit and mainly concerned with local interests. In the absence of an elective body to represent divergences of interest, it therefore shows a high degree of centralization in its political life. The Arab Higher Committee presented a 'common front' for all political parties. There was no opposition party. Decisions taken at the center. Differences of approach and interest, can be discerned, the more so from the strong pressure that is brought against them. In times of crisis, as in 1936–1938, such pressure has taken the form of intimidation and assassination. At present time, nonconformity regarding any important question on which the Arab Higher Committee has pronounced a policy is represented as disloyalty to the Arab nation.

Demise

The Arab League – led by Egypt – set up theAll-Palestine Government

, image =

, caption = Flag of the All-Palestine Government

, date = 22 September 1948

, state = All-Palestine Protectorate

, address = Gaza City, All-Palestine Protectorate (Sep.–Dec. 19 ...

(an Egyptian protectorate) in Gaza on 8 September 1948, while the 1948 Arab–Israeli War was in progress, under the nominal leadership of Amin al-Husayni, which was soon recognized by six of the seven Arab League members, the exception being Transjordan Transjordan may refer to:

* Transjordan (region), an area to the east of the Jordan River

* Oultrejordain, a Crusader lordship (1118–1187), also called Transjordan

* Emirate of Transjordan, British protectorate (1921–1946)

* Hashemite Kingdom of ...

. King Abdullah of Transjordan regarded the attempt to revive al-Husayni's Holy War Army

The Army of the Holy War or Holy War Army ( ar, جيش الجهاد المقدس; ''Jaysh al-Jihād al-Muqaddas'') was a Palestinian Arab irregular force in the 1947-48 Palestinian civil war led by Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni and Hasan Salama. The ...

as a challenge to his authority and all armed bodies operating in the areas controlled by the Arab Legion

The Arab Legion () was the police force, then regular army of the Emirate of Transjordan, a British protectorate, in the early part of the 20th century, and then of independent Jordan, with a final Arabization of its command taking place in 1 ...

were ordered to disband. Glubb Pasha

Lieutenant-General Sir John Bagot Glubb, KCB, CMG, DSO, OBE, MC, KStJ, KPM (16 April 1897 – 17 March 1986), known as Glubb Pasha, was a British soldier, scholar, and author, who led and trained Transjordan's Arab Legion between 1939 a ...

carried out the order ruthlessly and efficiently.Benny Morris (2003), p. 189.

After the war, the Arab Higher Committee was politically irrelevant, and banned from the Jordanian West Bank, as was the All-Palestine Government.

See also

*High Follow-Up Committee for Arab Citizens of Israel The High Follow-Up Committee for Arab citizens of Israel ( he, ועדת המעקב העליונה של הציבור הערבי בישראל, ar, لجنة المتابعة العليا للجماهير العربية في إسرائيل, also, High ...

* Bloudan Conference (1937)

The Bloudan Conference of 1937 (Arabic transliteration: ''al-Mu'tamar al-'Arabi al-Qawmi fi Bludan'') was the first pan-Arab summit held in Bloudan, Syria on 8 September 1937. The second Bloudan conference was held nine years later in 1946.

It w ...

* London Conference (1939)

The London Conference (1939), or ''St James's Palace Conference'', which took place between 7 February-17 March 1939, was called by the British Government to plan the future governance of Palestine and an end of the Mandate. It opened on 7 Fe ...

References

Bibliography

*Khalaf, Issa (1991). ''Politics in Palestine: Arab Factionalism and Social Disintegration, 1939–1948''. SUNY Press. *Levenberg, Haim (1993). ''Military Preparations of the Arab Community in Palestine: 1945–1948''. London: Routledge. *David Tal (2004) "Israel-Arab War, 1948 -1949/ Armistices" Routledge *Sayigh, Yezid (2000). ''Armed Struggle and the Search for State: The Palestinian National Movement, 1949–1993''. Oxford: Oxford University Press. * Segev, Tom. ''One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs Under the British Mandate''. Trans. Haim Watzman. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2001. {{Authority control 1936 establishments in Mandatory Palestine 1937 disestablishments in Mandatory Palestine Arab nationalism in Mandatory Palestine Arab nationalist organizations Politics of Mandatory Palestine Palestinian nationalism Riots and civil disorder in Mandatory Palestine 1948 disestablishments in Mandatory Palestine Organizations based in Mandatory Palestine Mandatory Palestine in World War II