Apsley Cherry-Garrard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Apsley George Benet Cherry-Garrard (2 January 1886 – 18 May 1959) was an English explorer of

His surname was changed to Cherry-Garrard by the terms of his great-aunt's will, through which his father inherited the Lamer Park estate near

His surname was changed to Cherry-Garrard by the terms of his great-aunt's will, through which his father inherited the Lamer Park estate near

With Wilson and

With Wilson and

Scott had left orders for dog-driver Meares and surgeon

Scott had left orders for dog-driver Meares and surgeon

Not long after his return to civilization in February 1913, Cherry-Garrard accompanied Edward Atkinson on his journey to China to assist Atkinson with his investigation on a type of parasitic flatworm that was causing schistosomiasis among British seamen. At the start of the

Not long after his return to civilization in February 1913, Cherry-Garrard accompanied Edward Atkinson on his journey to China to assist Atkinson with his investigation on a type of parasitic flatworm that was causing schistosomiasis among British seamen. At the start of the

In 1922, encouraged by his friend

In 1922, encouraged by his friend

Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

. He was a member of the ''Terra Nova'' expedition and is acclaimed for his 1922 account of this expedition, ''The Worst Journey in the World

''The Worst Journey in the World'' is a 1922 memoir by Apsley Cherry-Garrard of Robert Falcon Scott's ''Terra Nova'' expedition to the South Pole in 1910–1913. It has earned wide praise for its frank treatment of the difficulties of the exped ...

''.

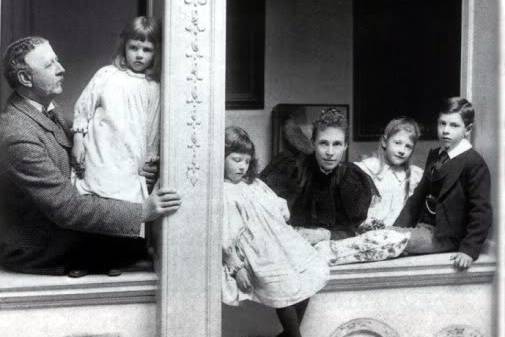

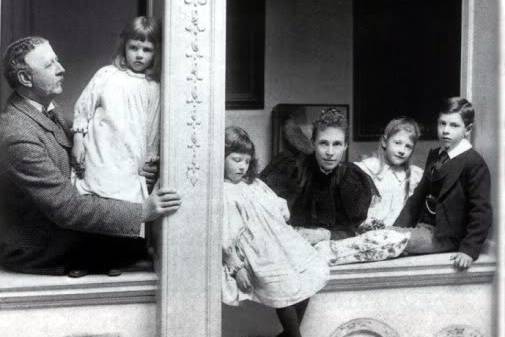

Early life

Born inBedford

Bedford is a market town in Bedfordshire, England. At the 2011 Census, the population of the Bedford built-up area (including Biddenham and Kempston) was 106,940, making it the second-largest settlement in Bedfordshire, behind Luton, whilst ...

, as Apsley George Benet Cherry, the eldest child of Apsley Cherry of Denford Park

Denford Park is a country house and surrounding estate in the English county of Berkshire, within the civil parish

In England, a civil parish is a type of administrative parish used for local government. It is a territorial designation whi ...

and his wife, Evelyn Edith (née Sharpin), daughter of Henry Wilson Sharpin of Bedford. He was educated at Winchester College

Winchester College is a public school (fee-charging independent day and boarding school) in Winchester, Hampshire, England. It was founded by William of Wykeham in 1382 and has existed in its present location ever since. It is the oldest of ...

and at Christ Church, Oxford where he read classics and modern history. While at Oxford, he rowed in the 1908 Christ Church crew which won the Grand Challenge Cup

The Grand Challenge Cup is a rowing competition for men's eights. It is the oldest and best-known event at the annual Henley Royal Regatta on the River Thames at Henley-on-Thames in England. It is open to male crews from all eligible rowing ...

at the Henley Royal Regatta.

His surname was changed to Cherry-Garrard by the terms of his great-aunt's will, through which his father inherited the Lamer Park estate near

His surname was changed to Cherry-Garrard by the terms of his great-aunt's will, through which his father inherited the Lamer Park estate near Wheathampstead

Wheathampstead is a village and civil parish in Hertfordshire, England, north of St Albans. The population of the ward at the 2001 census was 6,058. Included within the parish is the small hamlet of Amwell.

History

Settlements in this area were ...

, Hertfordshire. Apsley inherited the estate on his father's death in 1907.

Cherry-Garrard had always been enamoured of the stories of his father's achievements in India and China where he had fought with merit for the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

, and felt that he must live up to his father's example. In September 1907, Edward Adrian Wilson

Edward Adrian Wilson (23 July 1872 – 29 March 1912) was an English polar explorer, ornithologist, natural historian, physician and artist.

Early life

Born in Cheltenham on 23 July 1872, Wilson was the second son and fifth child of ...

met with Robert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott, , (6 June 1868 – c. 29 March 1912) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the ''Discovery'' expedition of 1901–1904 and the ill-fated ''Terra Nov ...

at Reginald Smith's home in Cortachy, to discuss another Antarctic expedition; Smith's young cousin Apsley Cherry-Garrard happened to visit and decided to volunteer.

Antarctica

At the age of 24, 'Cherry' was one of the youngest members of the ''Terra Nova'' expedition. This was Scott's second and last expedition to Antarctica. Cherry's application to join the expedition was initially rejected as Scott was looking for scientists, but he made a second application along with a promise of towards the cost of the expedition. Rejected a second time, he made the donation regardless. Struck by this gesture, and at the same time persuaded byEdward Adrian Wilson

Edward Adrian Wilson (23 July 1872 – 29 March 1912) was an English polar explorer, ornithologist, natural historian, physician and artist.

Early life

Born in Cheltenham on 23 July 1872, Wilson was the second son and fifth child of ...

, Scott agreed to take Cherry-Garrard as assistant zoologist. The expedition arrived in the Antarctic on 4 January 1911. During the remainder of the southern summer, from January to March, Cherry-Garrard helped lay depots of fuel and food on the intended route of the party which would attempt to reach the South Pole.

Winter journey

With Wilson and

With Wilson and Henry Robertson Bowers

Henry Robertson Bowers (29 July 1883 – c. 29 March 1912) was one of Robert Falcon Scott's polar party on the ill-fated Terra Nova expedition of 1910–1913, all of whom died during their return from the South Pole.

Early life

Bowers was b ...

, Cherry-Garrard made a trip to Cape Crozier

Cape Crozier is the most easterly point of Ross Island in Antarctica. It was discovered in 1841 during James Clark Ross's expedition of 1839 to 1843 with HMS ''Erebus'' and HMS ''Terror'', and was named after Francis Crozier, captain of HMS ' ...

on Ross Island in July 1911 during the austral winter in order to secure an unhatched emperor penguin egg to hopefully help scientists prove the evolutionary link between all birds and their reptile predecessors by analysis of the embryo. Cherry-Garrard suffered from a high degree of myopia, seeing little without the spectacles that he could not wear while sledging.

In almost total darkness, and with temperatures ranging from , they man-hauled their sledge from Scott's base at Cape Evans

Cape Evans is a rocky cape on the west side of Ross Island, Antarctica, forming the north side of the entrance to Erebus Bay.

History

The cape was discovered by the British National Antarctic Expedition, 1901–04, under Robert Falcon Scott, ...

to the far side of Ross Island. The party had two sledges, but the poor surface of the ice due to the extremely low temperatures meant that they could not drag both sledges as intended during parts of the outward journey. They were thus forced to relay, moving one sledge a certain distance before returning for the other. This highly inefficient means of travelling – walking for every one advanced – meant at times they could only travel a couple of miles each day.

Frozen and exhausted, they reached their destination in 19 days and built an improvised rock wall igloo with canvas roof on the slopes of Mount Terror just a few miles from the penguin colony at Cape Crozier. They managed to collect three penguin eggs intact before a force eleven blizzard struck on 22 July, ripping their tent away and carrying it off in the wind. The igloo roof lasted one more day before it too was ripped away by the wind, leaving the men in their sleeping bags under a thickening drift of snow, singing songs and hymns above the sounds of the storm to keep their spirits up.

When the winds subsided on 24 July, by great fortune they found their tent lodged in a hollow drift at the bottom of a steep slope half a mile away. Cherry-Garrard suffered such cold that he shattered most of his teeth due to chattering in the frigid temperatures. Desperately exhausted by the cold and lack of sleep, they left anything they didn't need behind and began their return journey. Only progressing a mile and a half some days, they eventually arrived back at Cape Evans shortly before midnight on 1 August. Cherry-Garrard later referred to this as the 'worst journey in the world' at the suggestion of his neighbour George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, and gave this title to his book recounting the fate of the 1910–1913 expedition.

Polar journey

On 1 November 1911, Cherry-Garrard set off to accompany the team that would make the attempt on theSouth Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipod ...

, along with three supporting parties of men, dogs and horses. At the foot of the Beardmore Glacier, the horses were shot and their flesh cached for food, while the dog teams turned back for base. At the top of the Beardmore Glacier, on 22 December, Cherry-Garrard was in the second supporting party to be sent home, arriving back at base on 26 January 1912.

One Ton Depot

Scott had left orders for dog-driver Meares and surgeon

Scott had left orders for dog-driver Meares and surgeon Edward L. Atkinson

Edward Leicester Atkinson, (23 November 1881 – 20 February 1929) was a Royal Navy surgeon and Antarctic explorer who was a member of the scientific staff of Captain Scott's Terra Nova Expedition, 1910–13. He was in command of the expedit ...

to take the dog teams south in early February 1912 to meet Scott's party on 1 March at latitude 82° or 82°30′S, and to assist his return journey. As Cecil Meares was not available for work, Atkinson had to attend to a medical emergency, and George Simpson was busy, the fateful choice fell on Cherry-Garrard. Belatedly, on 26 February 1912, Cherry-Garrard and dog handler Dimitri Gerov set off southwards and soon reached One Ton Depot on 3 March, and deposited additional food.

They waited there seven days hoping to meet the South Pole team. Cherry-Garrard and Dimitri then turned back on 10 March. Scott's party was at that time only , i.e. three dog marches south of One Ton Depot. Scott and his companions eventually reached a point south of One Ton Depot, where they starved or froze to death. Cherry-Garrard later wrote that "the primary object of this journey with the dog team was to hurry Scott and his companions home" but they "were never meant to be a relief journey".

He justified his decision to wait for a week and then turn back, stating that the poor weather, with daytime temperatures as low as , made further southward travel impossible, and the lack of dog food meant he would have had to kill dogs for food, against Atkinson's orders. They returned to base on 16 March empty-handed, immediately causing anxiety about Scott's fate.

Two days later, Cherry-Garrard fainted and became an invalid for the following days. Atkinson set forth to fetch Scott, but on 30 March was forced to turn back in the face of low temperatures, and concluded that Scott's party had perished.

Search journey

Cherry-Garrard was eventually appointed record keeper and continued zoological work. The scientific work continued through the winter and it was not until October 1912 that a team led by Atkinson and including Cherry-Garrard was able to head south to ascertain the fate of the South Pole team. On 12 November, the bodies of Scott, Wilson and Bowers were found in their tent, along with their diaries and records, and geological specimens they had hauled back from the mountains of the interior. Cherry-Garrard was deeply affected, particularly by the deaths of Wilson and Bowers, with whom he had made the journey to Cape Crozier.Later life

Not long after his return to civilization in February 1913, Cherry-Garrard accompanied Edward Atkinson on his journey to China to assist Atkinson with his investigation on a type of parasitic flatworm that was causing schistosomiasis among British seamen. At the start of the

Not long after his return to civilization in February 1913, Cherry-Garrard accompanied Edward Atkinson on his journey to China to assist Atkinson with his investigation on a type of parasitic flatworm that was causing schistosomiasis among British seamen. At the start of the Great War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Cherry-Garrard, along with the help of his mother and sisters, converted Lamer, his family estate, into a field hospital for wounded soldiers returning from the front. Cherry-Garrard journeyed to Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

in August 1914 with Major Edwin Richardson, a dog trainer who used dogs to sniff out wounded soldiers and founded the British War Dog School, to assist on the front with a pack of bloodhounds. Cherry-Garrard volunteered for this opportunity, in part due to his experience with handling dogs in Antarctica. After this opportunity was cut short, Cherry-Garrard returned to England and was eventually commissioned in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve and commanded a squadron of armoured cars in Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

. Invalided out in 1916, he suffered from clinical depression as well as ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a long-term condition that results in inflammation and ulcers of the colon and rectum. The primary symptoms of active disease are abdominal pain and diarrhea mixed with blood (hematochezia). Weight loss, fever, and ...

which had developed shortly after returning from Antarctica. His lifespan preceded the description and diagnosis of what is now called post-traumatic stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental and behavioral disorder that can develop because of exposure to a traumatic event, such as sexual assault, warfare, traffic collisions, child abuse, domestic violence, or other threats o ...

.

Although his psychological condition was never cured, the explorer was able to treat himself to some extent by writing down his experiences, although he spent many years bed-ridden due to his afflictions. He required repeated dental treatment because of the damage done to his teeth by the extreme cold. He many times revisited the question of what possible alternative choices and actions might have saved the South Pole team — most notably in his 1922 book ''The Worst Journey in the World

''The Worst Journey in the World'' is a 1922 memoir by Apsley Cherry-Garrard of Robert Falcon Scott's ''Terra Nova'' expedition to the South Pole in 1910–1913. It has earned wide praise for its frank treatment of the difficulties of the exped ...

''.

On 6 September 1939, Cherry-Garrard married Angela Katherine Turner (1916–2005), whom he had met during a Norwegian cruise in 1937. They had no children. After the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, ill health and taxes forced him to sell his family estate and move to a flat in London, where he died in Piccadilly on 18 May 1959. He is buried in the north-west corner of the churchyard of St Helen's Church, Wheathampstead.

Writings

In 1922, encouraged by his friend

In 1922, encouraged by his friend George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, Cherry-Garrard wrote ''The Worst Journey in the World''. Over 80 years later this book is still in print and is often cited as a classic of travel literature

The genre of travel literature encompasses outdoor literature, guide books, nature writing, and travel memoirs.

One early travel memoirist in Western literature was Pausanias, a Greek geographer of the 2nd century CE. In the early modern pe ...

, having been acclaimed as the greatest true adventure story ever written. It was published as Penguin Books

Penguin Books is a British publishing house. It was co-founded in 1935 by Allen Lane with his brothers Richard and John, as a line of the publishers The Bodley Head, only becoming a separate company the following year.The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

'', one critic said of the book that 'he has evidently, quite in the postwar manner resolved to say what he thinks and emphasize the "heroism" of the story as little as possible.'The Times. 5 December 1922. p. 12 More recently however, Roland Huntford

Roland Huntford ( Horwitch;Race To The Pole: Tragedy, Heroism, and Scott's Antarctic Quest, Ranulph Fiennes, Hyperion, 2004, p. 387 born 1927) is an author, principally of biographies of Polar explorers.

Background and education

Huntford, the ...

has dismissed the ''Worst Journey'' as "an immature but persuasive, highly charged apologia

An apologia (Latin for apology, from Greek ἀπολογία, "speaking in defense") is a formal defense of an opinion, position or action. The term's current use, often in the context of religion, theology and philosophy, derives from Justin Mar ...

".

Cherry-Garrard contributed an essay in remembrance of T. E. Lawrence

Thomas Edward Lawrence (16 August 1888 – 19 May 1935) was a British archaeologist, army officer, diplomat, and writer who became renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915–1918 ...

in the first edition of a volume edited by Lawrence's brother, A. W. Lawrence

Arnold Walter Lawrence (2 May 1900 – 31 March 1991) was a British authority on classical sculpture and architecture. He was Laurence Professor of Classical Archaeology at Cambridge University in the 1940s, and in the early 1950s in Accra he ...

, ''T. E. Lawrence, by His Friends''. Subsequent abridged editions omit his article. Cherry-Garrard hypothesises in this essay that Lawrence undertook extraordinary acts out of a sense of inferiority and cowardice and a need to prove himself. He suggests, too, that Lawrence's writings – as well as Cherry's own – were therapeutic and helped in dealing with the nervous breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitt ...

of the events they recount.

Legacy

The igloo on Cape Crozier was discovered by theCommonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition (CTAE) of 1955–1958 was a Commonwealth-sponsored expedition that successfully completed the first overland crossing of Antarctica, via the South Pole. It was the first expedition to reach the South ...

of 1957–1958. Only of the stone walls remained standing. Relics were removed and placed in museums in New Zealand.

The three penguin eggs brought back from Cape Crozier are now in the collection of the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleontology, climatology, and more. ...

, London.

References

Footnotes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * *External links

* * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Cherry-Garrard, Apsley 1886 births 1959 deaths Royal Navy personnel of World War I Royal Navy officers Military personnel from Bedford Burials in Hertfordshire 20th-century English writers Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford English polar explorers Explorers of Antarctica People educated at Winchester College People from Bedford People from Kintbury People from Wheathampstead Terra Nova expedition English memoirists Royal Naval Reserve personnel