Christianity in the 1st century covers the formative history of Christianity from the start of the

Christianity in the 1st century covers the formative history of Christianity from the start of the Etymology

Early Jewish Christians referred to themselves as "The Way" (), probably coming from Isaiah 40:3, "prepare the way of the Lord."Larry Hurtado (August 17, 2017)''"Paul, the Pagans’ Apostle"''

/ref>''Sect of “The Way”, “The Nazarenes” & “Christians” : Names given to the Early Church''

/ref> Since, the former was actually a quote of John the Baptizer about Yeshua, Jesus, more likely it connected to Yeshua's (Jesus') own words, declaring Himself the following, saying, "I am the WAY, the Truth, and the Life no one comes to the Father but by Me." (John 14:6) Other Jews also called them "the Nazarene (sect), Nazarenes," while another Jewish-Christian sect called themselves "Ebionites" (lit. "the poor"). According to Acts 11:26, the term "Christian" () was first used in reference to Jesus's Disciple (Christianity), disciples in the city of Early centers of Christianity#Antioch, Antioch, meaning "followers of Christ," by the non-Jewish inhabitants of Antioch. The earliest recorded use of the term "Christianity" () was by Ignatius of Antioch, in around 100 AD.

Origins

Jewish–Hellenistic background

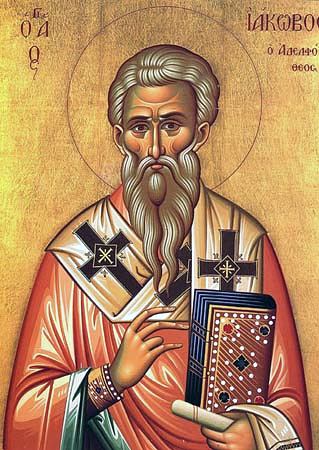

The earliest followers of Jesus were a sect of Jewish Apocalypticism, apocalyptic Jewish Christians within the realm of Second Temple Judaism. The early Christian groups were strictly Jewish, such as the Ebionites, and the early Christian community in Early centers of Christianity#Jerusalem, Jerusalem, led by James, brother of Jesus, James the Just, brother of Jesus. Christianity "emerged as a sect of Judaism in Roman Palestine" in the syncretistic Hellenistic world of the first century AD, which was dominated by Roman law and Greek culture. Hellenistic culture had a profound impact on the customs and practices of Jews everywhere. The inroads into Judaism gave rise to Hellenistic Judaism in the Jewish diaspora which sought to establish a Hellenistic Judaism, Hebraic-Jewish religious tradition within the culture and language of Hellenistic civilization, Hellenism. Hellenistic Judaism spread to Ptolemaic Egypt from the 3rd century BC, and became a notable ''religio licita'' after the Roman conquest of Greece, Asia (Roman province), Anatolia, Roman Syria, Syria, Roman Judea, Judea, and Roman Egypt, Egypt. During the early first century AD there were many competing Jewish sects in the Holy Land, and those that became Rabbinic Judaism and Proto-orthodox Christianity were but two of these. Philosophical schools included Pharisees, Sadducees, and Zealots (Judea), Zealots, but also other less influential sects, including the Essenes. The first century BC and first century AD saw a growing number of charismatic religious leaders contributing to what would become the Mishnah of Rabbinic Judaism; and theLife and ministry of Jesus

Sources

Christian sources, such as the four canonical gospels, the Pauline epistles, and the New Testament apocrypha, include detailed stories about Jesus, but scholars differ on the historicity of specific episodes described in the Biblical accounts of Jesus. The only two events subject to "almost universal assent" are that Baptism of Jesus, Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist and Crucifixion of Jesus, was crucified by the order of the Roman governor, Roman Prefect Pontius Pilate. States that baptism and crucifixion are "two facts in the life of Jesus command almost universal assent". The Gospels are theological documents, which "provide information the authors regarded as necessary for the religious development of the Christian communities in which they worked." They consist of short passages, ''pericopes'', which the Gospel-authors arranged in various ways as suited their aims. Non-Christian sources that are used to study and establish the historicity of Jesus include Jewish sources such as Josephus, and Roman sources such as Tacitus. These sources are compared to Christian sources such as the Pauline epistles and the Synoptic Gospels. These sources are usually independent of each other (e.g. Jewish sources do not draw upon Roman sources), and similarities and differences between them are used in the authentication process.Historical person

There is widespread disagreement among scholars on the details of the life of Jesus mentioned in the gospel narratives, and on the meaning of his teachings. Scholars often draw a distinction between the Historical Jesus, Jesus of history and the Christology, Christ of faith, and two different accounts can be found in this regard. Critical scholarship has discounted most of the narratives about Jesus as legendary, and the Historical Jesus, mainstream historical view is that while the gospels include many legendary elements, these are religious elaborations added to the accounts of a historical Jesus who was crucified under the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate in the 1st-century Roman province of Judea (Roman province), Judea. His remaining disciples later believed that he was resurrected.Ehrman, ''The Triumph of Christianity: How a Forbidden religion swept the World'' Academic scholars have Quest for the historical Jesus, constructed a variety of portraits and profiles for Jesus. Contemporary scholarship places Jesus firmly in the Jewish tradition,Theissen, Gerd and Annette Merz. The historical Jesus: a comprehensive guide. Fortress Press. 1998. translated from German (1996 edition) and the most prominent understanding of Jesus is as a Historical Jesus#Apocalyptic prophet, Jewish apocalyptic prophet or eschatological teacher. Other portraits are the charismatic healer, the Cynicism (philosophy), Cynic philosopher, the Jewish Messiah, and the prophet of social change.Ministry and eschatological expectations

In the canonical gospels, the ministry of Jesus begins with Baptism of Jesus, his baptism in the countryside of Judea (Roman province), Roman Judea and Transjordan (Bible), Transjordan, near the Jordan River, and ends in Jerusalem in Christianity, Jerusalem, following the Last Supper with his Disciple (Christianity), disciples. The Gospel of Luke () states that Jesus was "about 30 years of age" at the start of his Christian ministry, ministry.''The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament''by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 p. 140.Paul L. Maier "The Date of the Nativity and Chronology of Jesus" in ''Chronos, kairos, Christos: nativity and chronological studies'' by Jerry Vardaman, Edwin M. Yamauchi 1989 pp. 113–29 A chronology of Jesus typically has the date of the start of his ministry estimated at around AD 27–29 and the end in the range AD 30–36. In the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke), Jewish eschatology stands central. After being Baptism of Jesus, baptized by John the Baptist, Jesus teaches extensively for a year, or maybe just a few months, about the coming Kingdom of God (or, in Matthew, the Kingdom of Heaven (Gospel of Matthew), Kingdom of Heaven), in aphorisms and parables, using similes and figures of speech. In the Gospel of John, Jesus himself is the main subject. The Synoptics present different views on the Kingdom of God. While the Kingdom is essentially described as eschatology, eschatological (relating to the end of the world), becoming reality in the near future, some texts present the Kingdom as already being present, while other texts depict the Kingdom as a place in heaven that one enters after death, or as the presence of God on earth.. Jesus talks as expecting the coming of the "Son of man, Son of Man" from heaven, an Apocalypse, apocalyptic figure who would initiate "the coming judgment and the redemption of Israel." According to Davies, the Sermon on the Mount presents Jesus as the new Moses who brings a New Law (a reference to the Law of Moses, the Messianic Torah.

Death and resurrection

Jesus' life was ended by his Crucifixion of Jesus, execution by crucifixion. His early followers believed that three days after his death, Resurrection of Jesus, Jesus rose bodily from the dead. Paul's letters and the Gospels contain reports of a number of Post-resurrection appearances of Jesus, post-resurrection appearances. Progressively, Jewish scriptures were reexamined in light of Jesus's teachings to explain the crucifixion and Vision theory of Jesus' appearances, visionary post-mortem experiences of Jesus, and the resurrection of Jesus "signalled for earliest believers that the days of eschatological fulfilment were at hand."Larry Hurtado (December 4, 2018)

Jesus' life was ended by his Crucifixion of Jesus, execution by crucifixion. His early followers believed that three days after his death, Resurrection of Jesus, Jesus rose bodily from the dead. Paul's letters and the Gospels contain reports of a number of Post-resurrection appearances of Jesus, post-resurrection appearances. Progressively, Jewish scriptures were reexamined in light of Jesus's teachings to explain the crucifixion and Vision theory of Jesus' appearances, visionary post-mortem experiences of Jesus, and the resurrection of Jesus "signalled for earliest believers that the days of eschatological fulfilment were at hand."Larry Hurtado (December 4, 2018){{"'When Christians were Jews": Paula Fredriksen on "The First Generation{{'"

/ref> Some New Testament accounts were understood not as mere Vision theory of Jesus' appearances, visionary experiences, but rather as real appearances in which those present are told to touch and see. The resurrection of Jesus gave the impetus in certain Christian sects to the Session of Christ, exaltation of Jesus to the status of divine Son and Lord of God's Kingdom{{sfn, Ehrman, 2014, pp=109–10 and the resumption of their missionary activity. His followers expected Jesus to return within a generation and begin the Kingdom of God.{{r, group=web, "EB.Sanders.Pelikan.Jesus"

Apostolic Age

Jewish Christianity

{{Main, Jewish Christian {{See also, Early Christianity, Biblical law in Christianity After the death and resurrection of Jesus, Christianity first emerged as a sect of Judaism as practiced in the Judea (Roman province), Roman province of Judea.{{sfn, Burkett, 2002, p=3 The first Christians were all Jews, who constituted a Second Temple Judaism, Second Temple Jewish sect with an apocalyptic eschatology. Among other schools of thought, some Jews regarded Jesus as Kyrios, Lord and Resurrection of Jesus, resurrected messiah, and the eternally existing Son of God,{{sfn, McGrath, 2006, p=174{{sfn, Cohen, 1987, pp=167–68{{refn, group=note, According to Shaye J.D. Cohen, Jesus's failure to establish an independent Israel, and his death at the hands of the Romans, caused many Jews to reject him as the Messiah.{{sfn, Cohen, 1987, p=168 Jews at that time were expecting a military leader as a Messiah, such as Bar Kohhba. expecting the second coming of Jesus and the start of Kingship and kingdom of God, God's Kingdom. They pressed fellow Jews to prepare for these events and to follow "the way" of the Lord. They believed Yahweh to be the only true God, the god of Israel, and considered Jesus to be the messiah (Christ), as prophesied in the Hebrew Bible, Jewish scriptures, which they held to be authoritative and sacred. They held faithfully to the Torah,{{refn, group=note, Perhaps also Halacha, Jewish law which was being formalized at the same time including acceptance of Proselytes, Gentile converts based on a version of the Seven Laws of Noah, Noachide laws.{{refn, group=note, {{bibleverse, , Acts, 15 and {{bibleverse, , Acts, 21The Jerusalem ''ekklēsia''

{{Main, Jerusalem in Christianity

{{See also, Historical reliability of the Acts of the Apostles

The New Testament's Acts of the Apostles and Epistle to the Galatians record that an early Jewish Christian community{{refn, group=note, Hurtado: "She refrains from referring to this earliest stage of the "Jesus-community" as early "Christianity" and {{sic, comprised , hide=y, of "churches," as the terms carry baggage of later developments of "organized institutions, and of a religion separate from, different from, and hostile to Judaism" (185). So, instead, she renders ekklēsia as "assembly" (quite appropriately in my view, reflecting the quasi-official connotation of the term, often both in the LXX and in wider usage)." Early centers of Christianity#Jerusalem, centered on Jerusalem, and that its leaders reportedly included Saint Peter, Peter, James, brother of Jesus, James, the brother of Jesus, and John the Apostle.

The Jerusalem community "held a central place among all the churches," as witnessed by Paul's writings.{{sfn, Hurtado, 2005, p=160

Reportedly legitimised by Resurrection of Jesus, Jesus' appearance, Peter was the first leader of the Jerusalem ''ekklēsia''.{{sfn, Pagels, 2005, p=45{{sfn, Lüdemann, Özen, 1996, p=116

Peter was soon eclipsed in this leadership by James the Just, "the Brother of the Lord,"{{sfn, Pagels, 2005, pp=45–46{{sfn, Lüdemann, Özen, 1996, pp=116–17 which may explain why the early texts contain scant information about Peter.{{sfn, Lüdemann, Özen, 1996, pp=116–17 According to Lüdemann, in the discussions about the Paul and Judaism, strictness of adherence to the Jewish Law, the more conservative faction of James the Just gained the upper hand over the more liberal position of Peter, who soon lost influence.{{sfn, Lüdemann, Özen, 1996, pp=116–17 According to Dunn, this was not an "usurpation of power," but a consequence of Peter's involvement in missionary activities. The Desposyni, relatives of Jesus were generally accorded a special position within this community,{{sfn, Taylor, 1993, p=224 which also contributed to the ascendancy of James the Just in Jerusalem.{{sfn, Taylor, 1993, p=224

According to a tradition recorded by Eusebius and Epiphanius of Salamis, the Jerusalem church Flight to Pella, fled to Pella at the outbreak of the First Jewish–Roman War (AD 66–73).

The Jerusalem community consisted of "Hebrews," Jews speaking both Aramaic and Greek, and "Hellenists," Jews speaking only Greek, possibly diaspora Jews who had resettled in Jerusalem.{{sfn, Dunn, 2009, pp=246–47 According to Dunn, Paul's initial persecution of Christians probably was directed against these Greek-speaking "Hellenists" due to their anti-Temple attitude.{{sfn, Dunn, 2009, p=277 Within the early Jewish Christian community, this also set them apart from the "Hebrews" and their Tabernacle observance.{{sfn, Dunn, 2009, p=277

{{Main, Jerusalem in Christianity

{{See also, Historical reliability of the Acts of the Apostles

The New Testament's Acts of the Apostles and Epistle to the Galatians record that an early Jewish Christian community{{refn, group=note, Hurtado: "She refrains from referring to this earliest stage of the "Jesus-community" as early "Christianity" and {{sic, comprised , hide=y, of "churches," as the terms carry baggage of later developments of "organized institutions, and of a religion separate from, different from, and hostile to Judaism" (185). So, instead, she renders ekklēsia as "assembly" (quite appropriately in my view, reflecting the quasi-official connotation of the term, often both in the LXX and in wider usage)." Early centers of Christianity#Jerusalem, centered on Jerusalem, and that its leaders reportedly included Saint Peter, Peter, James, brother of Jesus, James, the brother of Jesus, and John the Apostle.

The Jerusalem community "held a central place among all the churches," as witnessed by Paul's writings.{{sfn, Hurtado, 2005, p=160

Reportedly legitimised by Resurrection of Jesus, Jesus' appearance, Peter was the first leader of the Jerusalem ''ekklēsia''.{{sfn, Pagels, 2005, p=45{{sfn, Lüdemann, Özen, 1996, p=116

Peter was soon eclipsed in this leadership by James the Just, "the Brother of the Lord,"{{sfn, Pagels, 2005, pp=45–46{{sfn, Lüdemann, Özen, 1996, pp=116–17 which may explain why the early texts contain scant information about Peter.{{sfn, Lüdemann, Özen, 1996, pp=116–17 According to Lüdemann, in the discussions about the Paul and Judaism, strictness of adherence to the Jewish Law, the more conservative faction of James the Just gained the upper hand over the more liberal position of Peter, who soon lost influence.{{sfn, Lüdemann, Özen, 1996, pp=116–17 According to Dunn, this was not an "usurpation of power," but a consequence of Peter's involvement in missionary activities. The Desposyni, relatives of Jesus were generally accorded a special position within this community,{{sfn, Taylor, 1993, p=224 which also contributed to the ascendancy of James the Just in Jerusalem.{{sfn, Taylor, 1993, p=224

According to a tradition recorded by Eusebius and Epiphanius of Salamis, the Jerusalem church Flight to Pella, fled to Pella at the outbreak of the First Jewish–Roman War (AD 66–73).

The Jerusalem community consisted of "Hebrews," Jews speaking both Aramaic and Greek, and "Hellenists," Jews speaking only Greek, possibly diaspora Jews who had resettled in Jerusalem.{{sfn, Dunn, 2009, pp=246–47 According to Dunn, Paul's initial persecution of Christians probably was directed against these Greek-speaking "Hellenists" due to their anti-Temple attitude.{{sfn, Dunn, 2009, p=277 Within the early Jewish Christian community, this also set them apart from the "Hebrews" and their Tabernacle observance.{{sfn, Dunn, 2009, p=277

Beliefs and practices

Creeds and salvation

{{Main, Salvation in Christianity The sources for the beliefs of the apostolic community include Oral gospel traditions, oral traditions (which included sayings attributed to Jesus, parables and teachings),{{sfn, Burkett, 2002 the Gospels, the New Testament NT epistles, epistles and possibly lost texts such as the Q source and the writings of Papias of Hierapolis, Papias. The texts contain the earliest Creed#Christian creeds, Christian creeds{{sfn, Cullmann, 1949, p={{pn, date=February 2022 expressing belief in the resurrected Jesus, such as {{bibleverse, 1, Corinthians, 15:3–41:{{sfn, Neufeld, 1964, p=47 {{Blockquote, [3] For I handed on to you as of first importance what I in turn had received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, [4] and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures,{{refn, group=note, name="third day", Se''Why was Resurrection on “the Third Day”? Two Insights''

for explanations on the phrase "third day." According to Pinchas Lapide, "third day" may refer to {{bibleref2, Hosea, 6:1–2:

"Come, let us return to the Lord;

for he has torn us, that he may heal us;

he has struck us down, and he will bind us up.

After two days he will revive us;

on the third day he will raise us up,

that we may live before him."

See also {{bibleref2, 2 Kings, 20:8: "Hezekiah said to Isaiah, 'What shall be the sign that the Lord will heal me, and that I shall go up to the house of the Lord on the third day?'" [5] and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. [6] Then he appeared to more than five hundred brothers and sisters at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have died. [7] Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles.{{cite web , website=oremus Bible Browser , url=http://bible.oremus.org/?passage=1+Corinthians+15:3%E2%80%9315:41&version=nrsv , title=1 Corinthians ''15:3–15:41'' The creed has been dated by some scholars as originating within the Jerusalem apostolic community no later than the 40s,{{sfn, O'Collins, 1978, p=112{{sfn, Hunter, 1973, p=100 and by some to less than a decade after Jesus' death,{{sfn, Pannenberg, 1968, p=90{{sfn, Cullmann, 1966, p=66 while others date it to about 56. Other early creeds include 1 John 4 ({{bibleverse, 1, John, 4:2), 2 Timothy 2 ({{bibleverse, 2, Timothy, 2:8) Romans 1 ({{bibleverse, , Romans, 1:3–4){{sfn, Pannenberg, 1968, pp=118, 283, 367 and 1 Timothy 3 ({{bibleverse, 1, Timothy, 3:16).

Christology

{{Main, Christology Two fundamentally different Christologies developed in the early Church, namely a "low" or Adoptionism, adoptionist Christology, and a "high" or "incarnation Christology."{{sfn, Ehrman, 2014, p=125 The chronology of the development of these early Christologies is a matter of debate within contemporary scholarship.{{sfn, Loke, 2017{{sfn, Ehrman, 2014{{sfn, Talbert, 2011, pp=3–6Larry Hurtado''The Origin of “Divine Christology”?''

/ref> The "low Christology" or "adoptionist Christology" is the belief "that God exalted Jesus to be his Son by raising him from the dead,"{{sfn, Ehrman, 2014, pp=120, 122 thereby raising him to "divine status."{{cite web, last1=Ehrman, first1=Bart D., author-link1=Bart D. Ehrman, title=Incarnation Christology, Angels, and Paul , url=https://ehrmanblog.org/incarnation-christology-angels-and-paul-for-members/, website=The Bart Ehrman Blog, access-date=May 2, 2018, date=February 14, 2013 According to the "evolutionary model"{{sfn, Netland, 2001, p=175 c.q. "evolutionary theories,"{{sfn, Loke, 2017, p=3 the Christological understanding of Christ developed over time,{{sfn, Mack, 1995, p={{pn, date=February 2022 {{sfn, Ehrman, 2003Bart Ehrman, ''How Jesus became God'', Course Guide as witnessed in the Gospels,{{sfn, Ehrman, 2014 with the earliest Christians believing that Jesus was a human who was exalted, c.q. Adoptionism, adopted as God's Son,{{sfn, Loke, 2017, pp=3–4{{sfn, Talbert, 2011, p=3 when he was resurrected. Later beliefs shifted the exaltation to his baptism, birth, and subsequently to the idea of his eternal existence, as witnessed in the Gospel of John. This evolutionary model was very influential, and the "low Christology" has long been regarded as the oldest Christology.{{sfn, Bird, 2017, pp=ix, xi{{sfn, Ehrman, 2014, p=132{{refn, group=note, Ehrman:

* "The earliest Christians held exaltation Christologies in which the human being Jesus was made the Son of God—for example, at his resurrection or at his baptism—as we examined in the previous chapter."{{sfn, Ehrman, 2014, p=132

* Here I’ll say something about the oldest Christology, as I understand it. This was what I earlier called a “low” Christology. I may end up in the book describing it as a “Christology from below” or possibly an “exaltation” Christology. Or maybe I’ll call it all three things [...] Along with lots of other scholars, I think this was indeed the earliest Christology.Bart Ehrman (6 Feb. 2013)

''The Earliest Christology''

/ref> The other early Christology is "high Christology," which is "the view that Jesus was a pre-existent divine being who became a human, did the Father’s will on earth, and then was taken back up into heaven whence he had originally come,"{{sfn, Ehrman, 2014, p=122 and from where he Christophany, appeared on earth. According to Hurtado, a proponent of an Christology#Development of "low Christology" and "high Christology", Early High Christology, the devotion to Jesus as divine originated in early Jewish Christianity, and not later or under the influence of pagan religions and Gentile converts.{{sfn, Hurtado, 2005, p=650 The Pauline letters, which are the earliest Christian writings, already show "a well-developed pattern of Christian devotion [...] already conventionalized and apparently uncontroversial."{{sfn, Hurtado, 2005, p=155 Some Christians began to worship Jesus is Lord, Jesus as a Lord.{{sfn, Dunn, 2005{{explain, date=February 2020

Eschatological expectations

{{Main, Jewish eschatology, Christian eschatology, Second coming Ehrman and other scholars believe that Jesus' early followers expected the immediate installment of the Kingdom of God, but that as time went on without this occurring, it led to a change in beliefs.{{sfn, Fredriksen, 2018Bart Ehrmann (June 4, 2016)''Were Jesus’ Followers Crazy? Was He?''

/ref> In time, the belief that Jesus' resurrection signaled the imminent coming of the Kingdom of God changed into a belief that the resurrection confirmed the Messianic status of Jesus, and the belief that Jesus would return at some indeterminate time in the future, the Second Coming, heralding the expected endtime.{{sfn, Fredriksen, 2018 When the Kingdom of God did not arrive, Christians' beliefs gradually changed into the expectation of an immediate reward in heaven after death, rather than to a future divine kingdom on Earth, despite the churches' continuing to use the major creeds' statements of belief in a coming resurrection day and world to come.{{Citation needed, date=August 2020, reason=Unsourced

Angels and Devils

Coming from a Jewish background, early Christians believed in Angel, angels (derived from the Greek word for "messengers").{{Cite book , last=Hitchcock , first=James , url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/796754060 , title=History of the Catholic Church : from the Apostolic Age to the Third Millennium , date=2012 , publisher=Ignatius Press , isbn=978-1-58617-664-8 , pages=23 , oclc=796754060 Specifically, early Christians wrote in the New Testament, New Testament books that angels "heralded Jesus' birth, Resurrection, and Ascension; ministered to Him while He was on Earth; and sing the praises of God through all eternity." Early Christians also believed that Guardian angel, protecting angels—assigned to each nation and even to each individual—would herald the Second Coming, lead the saints into Heaven in Christianity, Paradise, and cast the damned into Hell." Satan ("the adversary"), similar to descriptions in the Old Testament, appears in the New Testament "to accuse men of sin and to test their fidelity, even to the point of tempting Jesus."Practices

The Book of Acts reports that the early followers continued daily Second Temple, Temple attendance and List of Jewish prayers and blessings, traditional Jewish home prayer, Jewish liturgy, liturgical, a set of scriptural readings adapted from synagogue practice, and use of Religious music, sacred music in hymns and prayer. Other passages in the New Testament gospels reflect a similar observance of traditional Jewish piety such as baptism,{{cite web, url=http://jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=222&letter=B&search=Baptism, title=Baptism , website=jewishencyclopedia.com fasting, reverence for the Torah, and observance of Jewish holidays, Jewish holy days.{{sfn, White, 2004, p=127{{sfn, Ehrman, 2005, p=187Baptism

{{main, Baptism in early Christianity Early Christian beliefs regarding baptism probably predate the New Testament writings. It seems certain that numerous Jewish sects and certainly Jesus's disciples practised baptism. John the Baptist had baptized many people, before baptisms took place in the name of Jesus Christ. Paul likened baptism to being buried with Christ in his death.{{refn, group=note, Romans 6:3–4; Colossians 2:12Communal meals and Eucharist

{{Main, Agape feast, Eucharist Early Christian rituals included communal meals.{{cite book, last=Coveney, first=John, title=Food, Morals and Meaning: The Pleasure and Anxiety of Eating, date=2006, publisher=Routledge, language=en, isbn=978-1134184484, page=74, quote=For the early Christians, the ''agape'' signified the importance of fellowship. It was a ritual to celebrate the joy of eating, pleasure and company.{{cite book, last=Burns , first=Jim, title=Uncommon Youth Parties, date=2012, publisher=Gospel Light Publications, language=en, isbn=978-0830762132, page=37, quote=During the days of the Early Church, the believers would all gather together to share what was known as an agape feast, or "love feast." Those who could afford to bring food brought it to the feast and shared it with the other believers. The Eucharist was often a part of the Lovefeast, but between the latter part of the 1st century AD and 250 AD the two became separate rituals.{{cite book, last1=Walls, first1=Jerry L., last2=Collins, first2=Kenneth J., title=Roman but Not Catholic: What Remains at Stake 500 Years after the Reformation, date=2010, publisher=Baker Academic, language=en, isbn=978-1493411740, page=169, quote=So strong were the overtones of the Eucharist as a meal of fellowship that in its earliest practice it often took place in concert with the Agape feast. By the latter part of the first century, however, as Andrew McGowan points out, this conjoined communal banquet was separated into "a morning sacramental ritual [and a] prosaic communal supper."{{cite book, last=Davies, first=Horton, title=Bread of Life and Cup of Joy: Newer Ecumenical Perspectives on the Eucharist, date=1999, publisher=Wipf & Stock Publishers, isbn=978-1579102098, page=18 , quote=Agape (love feast), which ultimately became separate from the Eucharist...{{cite book, last=Daughrity, first=Dyron, title=Roots: Uncovering Why We Do What We Do in Church , date=2016 , publisher=ACU Press, language=en, isbn=978-0891126010, page=77, quote=Around AD 250 the lovefeast and Eucharist seem to separate, leaving the Eucharist to develop outside the context of a shared meal. Thus, in modern times the Lovefeast refers to a Christian ritual meal distinct from the Lord's Supper.{{cite dictionary , place=Oxford , title=Dictionary of the Christian Church , publisher=Oxford University Press , year=2005 , isbn=978-0-19-280290-3 , entry=agapeLiturgy

During the first three centuries of Christianity, the Divine Liturgy, Liturgical ritual was rooted in the Jewish Passover, Siddur, Passover Seder, Seder, and synagogue services, including the singing of hymns (especially the Psalms) and reading from the scriptures.{{cite web, url=http://jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=475&letter=L&search=Liturgy#1418, title=Liturgy , website=jewishencyclopedia.com Most early Christians did not own a copy of the works (some of which were still being written) that later became the Christian Bible or other church works accepted by some but not canonized, such as the writings of the Apostolic Fathers, or other works today called New Testament apocrypha. Similar to Judaism, much of the original church liturgy, liturgical services functioned as a means of learning these scriptures, which initially centered around the Septuagint and the Targums.{{cite book , editor1-last=Salvesen , editor1-first=Alison G , editor2-last=Law , editor2-first=Timothy Michael , title=The Oxford Handbook of the Septuagint , date=2021 , publisher=Oxford University Press , location=Oxford , isbn=978-0199665716 , page=22 At first, Christians continued to worship alongside Jewish believers, but within twenty years of Jesus' death, Sunday (the Lord's Day) was being regarded as the Sabbath in Christianity, primary day of worship.{{sfn, Davidson, 2005, p=115Emerging church – mission to the Gentiles

{{See also, Proto-orthodox Christianity With the start of their missionary activity, early Jewish Christians also started to attract proselytes, Gentiles who were fully or partly conversion to Judaism, converted to Judaism.{{sfn, Dunn, 2009, p=297{{refn, group=note, name="proselyteCatholic Encyclopedia: Proselyte

"The English term "proselyte" occurs only in the New Testament where it signifies a convert to the Jewish religion ({{bibleverse, , Matthew, 23:15, NAB; {{bibleverse, , Acts, 2:11, NAB; {{bibleverse-nb, , Acts, 6:5, NAB; etc.), though the same Greek word is commonly used in the Septuagint to designate a foreigner living in Judea. The term seems to have passed from an original local and chiefly political sense, in which it was used as early as 300 BC, to a technical and religious meaning in the Judaism of the New Testament epoch."

Growth of early Christianity

{{See also, Great Commission, Early centers of Christianity Christian missionary activity spread "the Way" and slowly created early centers of Christianity with Gentile adherents in the Greek primacy, predominantly Greek language, Greek-speaking Early centers of Christianity#Eastern Roman Empire, eastern half of the Roman Empire, and then throughout the Hellenistic world and even beyond the Roman Empire.{{sfn, Vidmar, 2005, pp=19–20{{sfn, Bokenkotter, 2004, p=18{{sfn, Franzen, 1988, p=29{{refn, group=note, Ecclesiastical historian Henry Hart Milman writes that in much of the first three centuries, even in the Latin-dominated western empire: "the Church of Rome, and most, if not all the Churches of the West, were, if we may so speak, Greek religious colonies [see Greek colonies for the background]. Their language was Greek, their organization Greek, their writers Greek, their scriptures Greek; and many vestiges and traditions show that their ritual, their Liturgy, was Greek."{{cite web, url=http://www.ellopos.net/elpenor/greek-orthodox-history.asp, title=Greek Orthodoxy – From Apostolic Times to the Present Day, work=ellopos.net Early Christian beliefs were proclaimed in ''kerygma'' (preaching), some of which are preserved in New Testament scripture. The early Gospel message spread oral gospel traditions, orally, probably originally in Aramaic language, Aramaic,{{sfn, Ehrman, 2012, pp=87–90 but almost immediately also in Koine Greek, Greek. A process of cognitive dissonance reduction may have contributed to intensive missionary activity, convincing others of the developing beliefs, reducing the cognitive dissonance created by the delay of the coming of the endtime. Due to this missionary zeal, the early group of followers grew larger despite the failing expectations.Bart Ehrmann (June 4, 2016)''Were Jesus’ Followers Crazy? Was He?''

/ref> The scope of the Jewish-Christian mission expanded over time. While Jesus limited his message to a Jewish audience in Galilee and Judea, after his death his followers extended their outreach to all of Israel, and eventually the whole Jewish diaspora, believing that the Second Coming would only happen when all Jews had received the Gospel.{{sfn, Fredriksen, 2018 Apostles and preachers Dispersion of the Apostles, traveled to Jewish Diaspora, Jewish communities around the Mediterranean Sea, and initially attracted Jewish converts.{{sfn, Bokenkotter, 2004, p=18 Within 10 years of the death of Jesus, apostles had attracted enthusiasts for "the Way" from First Christian church, Jerusalem to Antioch, Ephesus, Corinth, Thessalonica, Cyprus, Crete, Alexandria and Rome.{{sfn, Duffy, 2015, p=3{{sfn, Vidmar, 2005, pp=19–20{{sfn, Bokenkotter, 2004, p=18 Over 40 churches were established by 100,Hitchcock, ''Geography of Religion'' (2004), p. 281{{sfn, Bokenkotter, 2004, p=18 most in Early centers of Christianity#Anatolia, Asia Minor, such as the seven churches of Asia, and some in Greece in the Roman era and Roman Italy.{{Citation needed, date=August 2020, reason=Unsourced According to Fredriksen, when early Christians broadened their missionary efforts, they also came into contact with Gentiles attracted to the Jewish religion. Eventually, the Gentiles came to be included in the missionary effort of Hellenised Jews, bringing "all nations" into the house of God.{{sfn, Fredriksen, 2018 The "Hellenists," Greek-speaking diaspora Jews belonging to the early Jerusalem Jesus-movement, played an important role in reaching a Gentile, Greek audience, notably at Antioch, which had a large Jewish community and significant numbers of Gentile "God-fearers."{{sfn, Dunn, 2009, p=297 From Antioch, the mission to the Gentiles started, including Paul's, which would fundamentally change the character of the early Christian movement, eventually turning it into a new, Gentile religion.{{sfn, Dunn, 2009, p=302 According to Dunn, within 10 years after Jesus' death, "the new messianic movement focused on Jesus began to modulate into something different ... it was at Antioch that we can begin to speak of the new movement as 'Christianity'."{{sfn, Dunn, 2009, p=308 Christian groups and congregations first organized themselves loosely. In Paul the Apostle, Paul's time{{when, date=February 2020 there were no precisely delineated Ecclesiastical jurisdiction, territorial jurisdictions for bishops, Elder (Christianity), elders, and deacons.Stephen L Harris, Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.{{refn, group=note, Despite its mention of bishops, there is no clear evidence in the New Testament that supports the concepts of dioceses and monepiscopacy, i.e. the rule that all the churches in a geographic area should be ruled by a single bishop. According to Ronald Y. K. Fung, scholars point to evidence that Christian communities such as Rome had many bishops, and that the concept of monepiscopacy was still emerging when Ignatius was urging his tri-partite structure on other churches. {{See also, Apostolic see, Seven deacons

Paul and the inclusion of Gentiles

{{Main, Paul the ApostleConversion

{{Main, Conversion of Paul Paul's influence on Christian thinking is said to be more significant than that of any other authorship of the New Testament, New Testament author.{{sfn, Cross, Livingstone, 2005, loc="Paul" According to the New Testament, Saul of Tarsus first persecuted the early Jewish Christians, but then Conversion of Paul the Apostle, converted. He adopted the name Paul and started Proselytism, proselytizing among the Gentiles, calling himself "Apostle to the Gentiles." Paul was in contact with the early Christian community in First Christian church, Jerusalem, led by James the Just.{{sfn, Mack, 1997, p={{pn, date=February 2022 According to Mack, he may have been converted to another early strand of Christianity, with a High Christology.{{sfn, Mack, 1997, p=109 Fragments of their beliefs in an exalted and deified Jesus, what Mack called the "Christ cult," can be found in the writings of Paul.{{sfn, Mack, 1997, p={{pn, date=February 2022 {{refn, group=note, According to Mack, "Paul was converted to a Hellenized form of some Jesus movement that had already developed into a Christ cult. [...] Thus his letters serve as documentation for the Christ cult as well." Yet, Hurtado notes that Paul valued the linkage with "Jewish Christian circles in Roman Judea," which makes it likely that his Christology was in line with, and indebted to, their views.{{sfn, Hurtado, 2005, pp=156–157 Hurtado further notes that "[i]t is widely accepted that the tradition that Paul recites in 1 Corinthians 15:1-7 must go back to the Jerusalem Church."{{sfn, Hurtado, 2005, p=168Inclusion of Gentiles

{{Main, Paul the Apostle and Judaism, New Perspective on Paul, Pauline Christianity

{{See also, Circumcision in the Bible

Paul was responsible for bringing Christianity to Ephesus, Corinth, Philippi, and Thessalonica.{{sfn, Cross, Livingstone, 2005, pp=1243–1245{{better source needed, date=February 2020 According to Larry Hurtado, "Paul saw Jesus' resurrection as ushering in the eschatological time foretold by biblical prophets in which the pagan 'Gentile' nations would turn from their idols and embrace the one true God of Israel (e.g., {{bibleref2, Zechariah, 8:20–23), and Paul saw himself as specially called by God to declare God's eschatological acceptance of the Gentiles and summon them to turn to God."

According to Krister Stendahl, the main concern of Paul's writings on Jesus' role and salvation by faith is not the individual conscience of human sinners and their doubts about being chosen by God or not, but the main concern is the problem of the inclusion of Gentile (Greek) Torah-observers into God's covenant.{{sfn, Stendahl, 1963{{sfn, Dunn, 1982, p=n.49{{sfn, Finlan, 2004, p=2Stephen Westerholm (2015)

{{Main, Paul the Apostle and Judaism, New Perspective on Paul, Pauline Christianity

{{See also, Circumcision in the Bible

Paul was responsible for bringing Christianity to Ephesus, Corinth, Philippi, and Thessalonica.{{sfn, Cross, Livingstone, 2005, pp=1243–1245{{better source needed, date=February 2020 According to Larry Hurtado, "Paul saw Jesus' resurrection as ushering in the eschatological time foretold by biblical prophets in which the pagan 'Gentile' nations would turn from their idols and embrace the one true God of Israel (e.g., {{bibleref2, Zechariah, 8:20–23), and Paul saw himself as specially called by God to declare God's eschatological acceptance of the Gentiles and summon them to turn to God."

According to Krister Stendahl, the main concern of Paul's writings on Jesus' role and salvation by faith is not the individual conscience of human sinners and their doubts about being chosen by God or not, but the main concern is the problem of the inclusion of Gentile (Greek) Torah-observers into God's covenant.{{sfn, Stendahl, 1963{{sfn, Dunn, 1982, p=n.49{{sfn, Finlan, 2004, p=2Stephen Westerholm (2015)''The New Perspective on Paul in Review''

Direction, Spring 2015 · Vol. 44 No. 1 · pp. 4–15 The inclusion of Gentiles into early Christianity posed a problem for the Jewish identity of some of the early Christians:{{sfn, Bokenkotter, 2004, pp=19–21{{sfn, Hurtado, 2005, pp=162–165{{sfn, McGrath, 2006, pp=174–175 the new Gentile converts were not required to be Religious male circumcision, circumcised nor to observe the Law of Moses, Mosaic Law.{{sfn, Bokenkotter, 2004, p=19 Circumcision in particular was regarded as a token of the membership of the Abrahamic covenant, and the most traditionalist faction of Jewish Christians (i.e., converted Pharisees) insisted that Gentile converts had to be circumcised as well.{{Bibleref2c, Acts, 15:1{{sfn, Bokenkotter, 2004, pp=19–21{{sfn, Hurtado, 2005, pp=162–165{{sfn, McGrath, 2006, pp=174–75{{sfn, Cross, Livingstone, 2005, pp=1243–1245 By contrast, the rite of circumcision was considered execrable and repulsive during the period of Hellenization of the Eastern Mediterranean,{{cite journal , last=Hodges , first=Frederick M. , year=2001 , title=The Ideal Prepuce in Ancient Greece and Rome: Male Genital Aesthetics and Their Relation to Lipodermos, Circumcision, Foreskin Restoration, and the Kynodesme , journal=Bulletin of the History of Medicine , publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press , volume=75 , issue=Fall 2001 , pages=375–405 , url=http://www.cirp.org/library/history/hodges2/ , format=PDF , pmid=11568485 , doi=10.1353/bhm.2001.0119 , s2cid=29580193 , access-date=3 January 2020 {{cite journal , last1=Rubin , first1=Jody P. , title=Celsus' Decircumcision Operation: Medical and Historical Implications , journal=Urology (journal), Urology , publisher=Elsevier , volume=16 , issue=1 , pages=121–24 , date=July 1980 , url=http://www.cirp.org/library/restoration/rubin/ , pmid=6994325 , doi=10.1016/0090-4295(80)90354-4 , access-date=3 January 2020{{sfn, Fredriksen, 2018, pp=10–11{{cite web , url=http://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/4391-circumcision#anchor4 , title=Circumcision: In Apocryphal and Rabbinical Literature , last1=Kohler , first1=Kaufmann , last2=Hirsch , first2=Emil G. , last3=Jacobs , first3=Joseph , last4=Friedenwald , first4=Aaron , last5=Broydé , first5=Isaac , author1-link=Kaufmann Kohler , author2-link=Emil G. Hirsch , author3-link=Joseph Jacobs , author5-link=Isaac Broydé , publisher=Kopelman Foundation , website=Jewish Encyclopedia , access-date=3 January 2020 , quote=Contact with Grecian life, especially at the games of the arena [which involved nudity], made this distinction obnoxious to the Hellenists, or antinationalists; and the consequence was their attempt to appear like the Greeks by epispasm ("making themselves foreskins"; I Macc. i. 15; Josephus, "Ant." xii. 5, § 1; Assumptio Mosis, viii.; I Cor. vii. 18; Tosef., Shab. xv. 9; Yeb. 72a, b; Yer. Peah i. 16b; Yeb. viii. 9a). All the more did the law-observing Jews defy the edict of Antiochus Epiphanes prohibiting circumcision (I Macc. i. 48, 60; ii. 46); and the Jewish women showed their loyalty to the Law, even at the risk of their lives, by themselves circumcising their sons. and was especially adversed in Classical civilization both from Ancient Greece, ancient Greeks and Ancient Rome, Romans, which instead valued the foreskin positively.{{sfn, Fredriksen, 2018, pp=10–11 Paul objected strongly to the insistence on keeping all of the Jewish commandments,{{sfn, Cross, Livingstone, 2005, pp=1243–1245 considering it a great threat to his doctrine of salvation through faith in Christ.{{sfn, Hurtado, 2005, pp=162–165{{sfn, McGrath, 2006, pp=174–76 According to Paula Fredriksen, Circumcision controversy in early Christianity, Paul's opposition to male circumcison for Gentiles is in line with the Old Testament predictions that "in the last days the gentile nations would come to the God of Israel, as gentiles (e.g., {{bibleverse, Zechariah, 8:20–23, niv), not as proselytes to Israel." For Paul, Gentile male circumcision was therefore an affront to God's intentions. According to Larry Hurtado, "Paul saw himself as what Munck called a salvation-historical figure in his own right", who was "personally and singularly deputized by God to bring about the predicted ingathering (the "fullness") of the nations ({{bibleverse, Romans, 11:25, niv)." For Paul, Jesus' death and resurrection solved the problem of the exclusion of Gentiles from God's covenant,{{sfn, Cross, Livingstone, 2005, pp=1244–1245{{sfn, Mack, 1997, pp=91–92 since the faithful are redeemed by Participation in Christ, participation in Jesus' death and rising. In the Jerusalem ''ekklēsia'', from which Paul received the creed of {{bibleverse, 1 Corinthians, 15:1–7, NRSV, the phrase "died for our sins" probably was an apologetic rationale for the death of Jesus as being part of God's plan and purpose, as evidenced in the Scriptures. For Paul, it gained a deeper significance, providing "a basis for the salvation of sinful Gentiles apart from the Torah."{{sfn, Hurtado, 2005, p=131 According to E. P. Sanders, Paul argued that "those who are baptized into Christ are baptized into his death, and thus they escape the power of sin [...] he died so that the believers may die with him and consequently live with him."E.P. Sanders

''Saint Paul, the Apostle''

Encyclopedia Britannica By this participation in Christ's death and rising, "one receives forgiveness for past offences, is liberated from the powers of sin, and receives the Spirit." Paul insists that salvation is received by the grace of God; according to Sanders, this insistence is in line with Second Temple Judaism of c. 200 BC until 200 AD, which saw God's covenant with Israel as an act of grace of God. Observance of the Law is needed to maintain the covenant, but the covenant is not earned by observing the Law, but by the grace of God.Jordan Cooper

''E.P. Sanders and the New Perspective on Paul''

/ref> These divergent interpretations have a prominent place in both Paul's writings and in Acts. According to {{bibleverse, Galatians, 2:1–10, niv and Acts 15, Acts chapter 15, fourteen years after his conversion Paul visited the "Pillars of Jerusalem", the leaders of the Jerusalem ''ekklēsia''. His purpose was to compare his Gospel{{clarify, date=February 2020 with theirs, an event known as the Council of Jerusalem. According to Paul, in his letter to the Galatians,{{refn, group=note, Four years after the Council of Jerusalem, Paul wrote to the Galatians about the issue, which had become a serious controversy in their region. There was a burgeoning movement of Judaizers in the area that advocated adherence to the Mosaic Law, including circumcision. According to McGrath, Paul identified James, brother of Jesus, James the Just as the motivating force behind the Judaizing movement. Paul considered it a great threat to his doctrine of salvation through faith and addressed the issue with great detail in {{bibleref, Galatians, 3, NRSV.{{sfn, McGrath, 2006, pp=174–75 they agreed that his mission was to be among the Gentiles. According to Acts, Paul made an argument that circumcision was not a necessary practice, vocally supported by Peter.{{sfn, McGrath, 2006, p=174McManners, ''Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity'' (2002), p. 37{{refn, group=note, According to 19th-century German theologian F. C. Baur early Christianity was dominated by the conflict between Saint Peter, Peter who was Biblical law in Christianity#The Torah Submissive view, law-observant, and Paul the Apostle, Paul who advocated partial or even complete Antinomianism, freedom from the Law.{{citation needed, date=March 2019 Scholar James D. G. Dunn has proposed that Peter was the "bridge-man" between the two other prominent leaders: Paul and James the Just. Paul and James were both heavily identified with their own "brands" of Christianity. Peter showed a desire to hold on to his Jewish identity, in contrast with Paul. He simultaneously showed a flexibility towards the desires of the broader Christian community, in contrast to James. Marcion and his followers stated that the polemic against false apostles in Epistle to the Galatians, Galatians was aimed at Peter, James, brother of Jesus, James and John the Evangelist, John, the "Pillars of the Church", as well as the "false" gospels circulating through the churches at the time. Irenaeus and Tertullian argued against Marcionism's elevation of Paul and stated that Peter and Paul were equals among the apostles. Passages from Galatians were used to show that Paul respected Peter's office and acknowledged a shared faith.{{sfn, Keck, 1988, p={{pn, date=February 2022 {{sfn, Pelikan, 1975, p=113 While the Council of Jerusalem was described as resulting in an agreement to allow Gentile converts exemption from most Mitzvot, Jewish commandments, in reality a stark opposition from "Hebrew" Jewish Christians remained,{{sfn, Cross, Livingstone, 2005, p=1244 as exemplified by the Ebionites. The relaxing of requirements in Pauline Christianity opened the way for a much larger Christian Church, extending far beyond the Jewish community. The inclusion of Gentiles is reflected in Luke-Acts, which is an attempt to answer a theological problem, namely how the Messiah of the Jews came to have an overwhelmingly non-Jewish church; the answer it provides, and its central theme, is that the message of Christ was sent to the Gentiles because the Rejection of Jesus, Jews rejected it.{{sfn, Burkett, 2002, p=263

Persecutions

{{See also, Persecution of Christians in the New Testament , Persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire Persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire occurred sporadically over a period of over two centuries. For most of the first three hundred years of Christian history, Christians were able to live in peace, practice their professions, and rise to positions of responsibility.{{cite book, last=Moss, first=Candida, author-link=Candida Moss, title=The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom, date=2013, publisher=HarperCollins, isbn=978-0-06-210452-6, page=129 Sporadic persecution took place as the result of local pagan populations putting pressure on the imperial authorities to take action against the Christians in their midst, who were thought to bring misfortune by their refusal to honour the gods.{{sfn, Croix, 2006, pp=105–52 Only for approximately ten out of the first three hundred years of the church's history were Christians executed due to orders from a Roman emperor. The first persecution of Christians organised by the Roman government took place under the emperor Nero in 64 AD after the Great Fire of Rome.{{sfn, Croix, 2006, pp=105–52 There was no empire-wide persecution of Christians until the reign of Decius in the third century.Martin, D. 2010"The 'Afterlife' of the New Testament and Postmodern Interpretation"

{{Webarchive, url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160608093412/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v1Bh_SAEU90 , date=2016-06-08

lecture transcript

{{Webarchive, url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160812141627/https://cosmolearning.org/video-lectures/the-afterlife-of-the-new-testament-and-postmodern-interpretation-6819/ , date=2016-08-12 ). Yale University. The Edict of Serdica was issued in 311 by the Roman emperor Galerius, officially ending the Diocletianic persecution of Christianity in the East. With the passage in 313 AD of the Edict of Milan, in which the Roman Emperors Constantine the Great and Licinius legalised the Christianity, Christian religion, persecution of Christians by the Roman state ceased.{{cite web , title=Persecution in the Early Church , url=http://www.religionfacts.com/christianity/history/persecution.htm , publisher=Religion Facts , access-date=2014-03-26 , archive-date=2014-03-25 , archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140325154903/http://religionfacts.com/christianity/history/persecution.htm , url-status=dead

Development of the Biblical canon

{{Main, Development of the Christian biblical canon

In an ancient culture before the printing press and the majority of the population illiterate, most early Christians likely did not own any Christian texts. Much of the original church liturgical services functioned as a means of learning Christian theology. A final uniformity of liturgical services may have become solidified after the church established a Biblical canon, possibly based on the Apostolic Constitutions and Clementine literature. Pope Clement I, Clement (d. 99) writes that liturgy, liturgies are "to be celebrated, and not carelessly nor in disorder" but the final uniformity of liturgical services only came later, though the ''Liturgy of St James'' is traditionally associated with James the Just.

Books not accepted by Pauline Christianity are termed biblical apocrypha, though the exact list varies from denomination to denomination.{{Citation needed, date=August 2020, reason=Unsourced

{{Main, Development of the Christian biblical canon

In an ancient culture before the printing press and the majority of the population illiterate, most early Christians likely did not own any Christian texts. Much of the original church liturgical services functioned as a means of learning Christian theology. A final uniformity of liturgical services may have become solidified after the church established a Biblical canon, possibly based on the Apostolic Constitutions and Clementine literature. Pope Clement I, Clement (d. 99) writes that liturgy, liturgies are "to be celebrated, and not carelessly nor in disorder" but the final uniformity of liturgical services only came later, though the ''Liturgy of St James'' is traditionally associated with James the Just.

Books not accepted by Pauline Christianity are termed biblical apocrypha, though the exact list varies from denomination to denomination.{{Citation needed, date=August 2020, reason=Unsourced

Old Testament

{{Main, Development of the Old Testament canon The Biblical canon began with the Jewish Scriptures. The Koine Greek translation of the Jewish scriptures, later known as the ''Septuagint''{{sfn, McDonald, Sanders, 2002, p=72 and often written as "LXX," was the dominant translation from very early on.{{cite web, url=http://www.ccel.org/ccel/swete/greekot/Page_112.html , title=Swete's Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek, p. 112 , publisher=Ccel.org , access-date=2019-05-20 Perhaps the earliest Christian canon is the ''Bryennios List'', dated to around 100, which was found by Philotheos Bryennios in the Codex Hierosolymitanus. The list is written in Koine Greek, Aramaic and Hebrew language, Hebrew. In the 2nd century, Melito of Sardis called the Jewish scriptures the "Old Testament" and also specified an early Melito's canon, canon.{{Citation needed, date=August 2020, reason=Unsourced Jerome (347–420) expressed his preference for adhering strictly to the Hebrew text and canon, but his view held little currency even in his own day.New Testament

{{Books of the New Testament {{Main, Development of the New Testament canon The New Testament (often compared to the New Covenant) is the second major division of the Christian Bible. The books of the canon of the New Testament include the Canonical Gospels, Acts of the Apostles, Acts, letters of the Apostles in the New Testament, Apostles, and Book of Revelation, Revelation. The original texts were written by various authors, most likely sometime between c. AD 45 and 120 AD,{{cite book , author=Bart D. Ehrman , title=The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings , url= https://books.google.com/books?id=xpoNAQAAMAAJ , year=1997 , publisher=Oxford University Press , isbn=978-0-19-508481-8 , page=8 , quote=The New Testament contains twenty-seven books, written in Greek, by fifteen or sixteen different authors, who were addressing other Christian individuals or communities between the years 50 and 120 (see box 1.4). As we will see, it is difficult to know whether any of these books was written by Jesus' own disciples. in Koine Greek, the lingua franca of the eastern part of the Roman Empire, though there is also a minority argument for Aramaic primacy. They were not defined as "canon" until the 4th century. Some were disputed, known as the Antilegomena.{{Citation needed, date=August 2020, reason=Unsourced Writings attributed to the Apostles in the New Testament, Apostles circulated among the Early centers of Christianity, earliest Christian communities. The Pauline epistles were circulating, perhaps in collected forms, by the end of the 1st century AD.{{refn, group=note, Three forms are postulated, from {{Citation , title = The Canon Debate , chapter = 18 , page = 300, note 21 , first = Harry Y , last = Gamble , quote = (1) Marcion's collection that begins with Galatians and ends with Philemon; (2) Papyrus 46, dated about 200, that follows the order that became established except for reversing Ephesians and Galatians; and (3) the letters to seven churches, treating those to the same church as one letter and basing the order on length, so that Corinthians is first and Colossians (perhaps including Philemon) is last.Early orthodox writings – Apostolic Fathers

The Church Fathers are the early and influential Christian theology, Christian theologians and writers, particularly those of the first five centuries of Christian history. The earliest Church Fathers, within two generations of the Twelve Apostles of Christ, are usually called Apostolic Fathers for reportedly knowing and studying under the apostles personally. Important Apostolic Fathers include Clement of Rome (d. AD 99),Will Durant, Durant, Will. ''Caesar and Christ''. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1972 Ignatius of Antioch (d. AD 98 to 117) and Polycarp of Smyrna (AD 69–155). The earliest Christian writings, other than those collected in the New Testament, are a group of letters credited to the Apostolic Fathers. Their writings include the Epistle of Barnabas and the Epistles of Clement. The Didache and Shepherd of Hermas are usually placed among the writings of the Apostolic Fathers, although their authors are unknown.{{Citation needed, date=August 2020, reason=Unsourced Taken as a whole, the collection is notable for its literary simplicity, religious zeal and lack of Hellenistic philosophy or rhetoric. They contain early thoughts on the organisation of the Christian ''ekklēsia'', and are historical sources for the development of an early Church structure.{{Citation needed, date=August 2020, reason=Unsourced In his letter 1 Clement, Clement of Rome calls on the Christians of Corinth to maintain harmony and order. Some see his epistle as an assertion of Rome's authority over the church in Corinth and, by implication, the beginnings of papal supremacy.{{cite web, url=http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04012c.htm, title=Pope St. Clement I, website=newadvent.org Clement refers to the leaders of the Corinthian church in his letter as bishops and presbyters interchangeably, and likewise states that the bishops are to lead God's flock by virtue of the chief shepherd (presbyter), Jesus Christ.{{Citation needed, date=August 2020, reason=Unsourced Ignatius of Antioch advocated the authority of the apostolic episcopacy (bishops). The Didache (late 1st century){{sfn, Draper, 2006, p=178 is an anonymous Jewish-Christian work. It is a pastoral manual dealing with Christian lessons, rituals, and Church organization, parts of which may have constituted the first written catechism, "that reveals more about how Jewish-Christians saw themselves and how they adapted their Judaism for Gentiles than any other book in the Christian Scriptures."{{sfn, Milavec, 2003, p=viiSplit of early Christianity and Judaism

Split with Judaism

{{Main, Split of early Christianity and Judaism {{See also, Schisms among the Jews, List of events in early Christianity There was a slowly growing chasm between Gentile Christians, and Jews and Jewish Christians, rather than a sudden split. Even though it is commonly thought that Paul established a Gentile church, it took a century for a complete break to manifest. Growing tensions led to a starker separation that was virtually complete by the time Jewish Christians refused to join in the Bar Kokhba revolt, Bar Kokhba Jewish revolt of 132.{{sfn, Davidson, 2005, p=146 Certain events are perceived as pivotal in the growing rift between Christianity and Judaism.{{Citation needed, date=August 2020, reason=Unsourced The Siege of Jerusalem (70), destruction of Jerusalem and the consequent dispersion of Jews and Jewish Christians from the city (after the Bar Kokhba revolt) ended any pre-eminence of the Jewish-Christian leadership in Jerusalem. Early Christianity grew further apart from Judaism to establish itself as a predominantly Gentile religion, and Early centers of Christianity#Antioch, Antioch became the first Gentile Christian community with stature.{{sfn, Franzen, 1988, p=25 The hypothetical Council of Jamnia c. 85 is often stated to have condemned all who claimed the Messiah had already come, and Christianity in particular, excluding them from attending synagogue.{{sfn, Wylen, 1995, p=190{{sfn, Berard, 2006, pp=112–113{{sfn, W1992, pp=164–165{{quote needed, date=January 2020 However, the formulated prayer in question (birkat ha-minim) is considered by other scholars to be unremarkable in the history of Jewish and Christian relations. There is a paucity of evidence for Jewish persecution of "heretics" in general, or Christians in particular, in the period between 70 and 135. It is probable that the condemnation of Jamnia included many groups, of which the Christians were but one, and did not necessarily mean excommunication. That some of the later church fathers only recommended against synagogue attendance makes it improbable that an anti-Christian prayer was a common part of the synagogue liturgy. Jewish Christians continued to worship in synagogues for centuries.{{sfn, Wylen, 1995, p=190{{sfn, W1992, pp=164–165 During the late 1st century, Judaism was a legal religion with the protection of Roman law, worked out in compromise with the Roman state over two centuries (see Anti-Judaism#Pre-Christian Roman Empire, Anti-Judaism in the Roman Empire for details). In contrast, Christianity was not legalized until the 313 Edict of Milan. Observant Jews had special rights, including the privilege of abstaining from civic pagan rites. Christians were initially identified with the Jewish religion by the Romans, but as they became more distinct, Christianity became a problem for Roman rulers. Around the year 98, the emperor Nerva decreed that Christians did not have to pay the Fiscus Iudaicus, annual tax upon the Jews, effectively recognizing them as distinct from Rabbinic Judaism. This opened the way to Christians being persecuted for disobedience to the emperor, as they refused to worship the Imperial cult (ancient Rome), state pantheon.{{sfn, Wylen, 1995, pp=190–192{{sfn, Dunn, 1999, pp=33–34{{sfn, BoatwGargola, Talbert, 2004, p=426 From c. 98 onwards a distinction between Christians and Jews in Roman literature becomes apparent. For example, Pliny the Younger postulates that Christians are not Jews since they do not pay the tax, in his letters to Trajan.{{sfn, Wylen, 1995, pp=190–192{{sfn, Dunn, 1999, pp=33–34Later rejection of Jewish Christianity

Jewish Christians constituted a separate community from the Pauline Christianity, Pauline Christians but maintained a similar faith. In Christian circles, ''Nazarene (sect), Nazarene'' later came to be used as a label for those faithful to Jewish Law, in particular for a certain sect. These Jewish Christians, originally the central group in Christianity, generally holding the same beliefs except in their adherence to Jewish law, were not deemed heretical until the dominance of orthodoxy in the Christianity in the 4th century, 4th century.{{sfn, Dauphin, 1993, pp=235, 240–242 The Ebionites may have been a splinter group of Nazarenes, with disagreements over Christology and leadership. They were considered by Gentile Christians to have unorthodox beliefs, particularly in relation to their views of Christ and Gentile converts. After the condemnation of the Nazarenes, ''Ebionite'' was often used as a general pejorative for all related "heresies".{{sfn, Tabor, 1998{{sfn, Esler, 2004, pp=157–159 There was a post-Nicene "double rejection" of the Jewish Christians by both Gentile Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism. The true end of ancient Jewish Christianity occurred only in the 5th century. Gentile Christianity became the dominant strand of orthodoxy and imposed itself on the previously Jewish Christian sanctuaries, taking full control of those houses of worship by the end of the 5th century.{{sfn, Dauphin, 1993, pp=235, 240–242{{refn, group=note, Jewish Virtual Library: "A major difficulty in tracing the growth of Christianity from its beginnings as a Jewish messianism, Jewish messianic sect, and its relations to the various other normative-Jewish, sectarian-Jewish, and Christian-Jewish groups is presented by the fact that what ultimately became normative Christianity was originally but one among various contending Christian trends. Once the "gentile Christian" trend won out, and the Pauline theology, teaching of Paul of Tarsus, Paul became accepted as expressing the doctrine of the Church, the Jewish Christian groups were pushed to the margin and ultimately excluded as heretical. Being rejected both by normative Judaism and the Church, they ultimately disappeared. Nevertheless, several Jewish Christian sects (such as the Nazarene (sect), Nazarenes, Ebionites, Elchasaites, and others) existed for some time, and a few of them seem to have endured for several centuries. Some sects saw in Jesus mainly a Prophet#Judaism, prophet and not the "Christ," others seem to have believed in him as the Messiah, but did not draw the Christology, christological and other conclusions that subsequently became fundamental in the teaching of the Church (the divinity of the Christ, Trinity, trinitarian conception of the Godhead, Abrogation of Old Covenant laws, abrogation of the Law). After the disappearance of the early Jewish Christian sects and the triumph of gentile Christianity, to become a Christian meant, for a Jew, to Apostasy in Judaism, apostatize and to leave the Jewish community.{{r, group=web, "JVL"Timeline

{{hidden, 1st century timeline, {{disputed, talkpage=Talk:Christianity in the 1st century#Bethlehem, date=March 2019 ''Earliest dates must all be considered approximate'' *6 BC Judean King Herod Archelaus deposed by the Roman Emperor Augustus; Samaria, Judea, and Idumea annexed as Iudaea Province under direct Roman administration, capital at Caesarea Maritima, Caesarea, Quirinius became Legatus, Legate (Governor) of Roman Syria, Syria, conducted Census of Quirinius, opposed by the ZealotsJA18

{{bibleverse, , Luke, 2:1–3, {{bibleverse, , Acts, 5:37). *c. 4 BC Nativity of Jesus, Jesus is born in Bethlehem, Judaea (Roman province), Judea (according to the Gospels of Gospel of Luke, Luke and Gospel of Matthew, Matthew) *7–26 AD Brief period of peace, relatively free of revolt and bloodshed in Iudaea and Galilee *9 Pharisee leader Hillel the Elder dies, temporary rise of Shammai *14–37 Rule of the Roman Emperor Tiberius *18–36 Caiaphas, appointed List of High Priests of Israel, High Priest of Herod's Temple by Prefect Valerius Gratus, deposed by Syrian Legate Lucius Vitellius *19 Jews, Jewish Proselytes, Astrologers, expelled from Rome{{cite web, url=http://jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=352&letter=R&search=Sejanus#1006, title=Rome , website=jewishencyclopedia.com *26–36 Pontius Pilate, Prefect (governor) of Iudaea, recalled to Rome by Syrian Legate Vitellius on complaints of excess violence (JA18.4.2) *28 or 29 John the Baptist began his Religious ministry (Christian), ministry in the "15th year of Tiberius" ({{bibleverse, Luke, , 3:1–2) ({{bibleverse, , Matt, 3:1–2) *30 – Great Commission of Jesus to go and make disciples of all nations;{{sfn, Barnett, 2002, p=23 *30–36 Crucifixion of Jesus, Jesus is crucified on order of Pontius Pilate. Christians believe he Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead 3 days later. Pentecost, a day in which 3000 Jews from a variety of Mediterranean-basin nations are converted to faith in Jesus Christ. *34 – Philip the Evangelist, Philip baptizes a convert in History of Gaza#Roman empire, Gaza, an Ethiopian eunuch who was already a God-fearer.{{sfn, Hurtado, 2005, pp=15, 38-39, 41-42 *39 – St. Peter, Peter preaches to a Gentile audience in the house of the Roman soldier Cornelius the Centurion, Cornelius, who was already a God-fearer.{{sfn, Hurtado, 2005, pp=15, 38-39, 41-42 *37–41 Crisis under Caligula *42 – Mark the Evangelist, Mark goes to Roman Egypt, Egypt{{sfn, Kane, 1982, p=10 *44? James the Great: According to ancient local tradition, on 2 January of the year AD 40, the Virgin Mary appeared to James on a Our Lady of the Pillar, Pilar on the bank of the Ebro River at Caesaraugusta, while he was preaching the Gospel in Hispania (modern-day Spain). Following that apparition, James returned to Judea, where he was beheaded by King Herod Agrippa I in the year 44 during a Passover (Nisan 15) ({{bibleverse, Acts, , 12:1–3). *44 Death of Herod Agrippa I

JA19

8.2, {{bibleverse, , Acts, 12:20–23) *44–46? Theudas beheaded by Procurator (Roman), Procurator Cuspius Fadus for saying he would part the Jordan river (like Moses and the Red Sea or Joshua and the Jordan)

JA20

5.1, {{bibleverse, , Acts, 5:36–37 places it before the Census of Quirinius) *45–49? Mission of Barnabas and Paul ({{bibleverse, , Acts, 13:1–14:28) to the island of Cyprus, Antioch, Pisidia, Pisidian Antioch, Iconium, Lystra, and Derbe (there they were called "gods ... in human form"), then return to Syrian Antioch

Map1

*47? Saint Thomas Christians, St. Thomas Christianity, now in several forms, is begun in Christianity in India, India by Thomas the Apostle, Thomas. * 47 – Paul of Tarsus, Paul (formerly known as Saul of Tarsus in Cilicia, Tarsus) begins his first missionary journey to Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey).{{sfn, Walker, 1959, p=26 *48–100 Agrippa II, Herod Agrippa II appointed Hasmonean, King of the Jews by Claudius, seventh and last of the Herodians *50 Passover riot in Jerusalem, 20–30,000 killed (JA20.5.3

JW2

12.1) *50 – Council of Jerusalem on admitting Gentiles into the Church{{sfn, Walker, 1959, p=26 *50? Council of Jerusalem and the "Apostolic Decree", {{bibleverse, Acts, , 15:1–35, same as {{bibleverse, , Galatians, 2:1–10?, which is followed by the "Incident at Antioch", at which Paul publicly accused Peter of "Judaizers, Judaizing" towards the Gentiles ({{bibleverse-nb, , Galatians, 2:11–21){{cite journal , last=Dunn , first=James D. G. , author-link=James Dunn (theologian) , date=Autumn 1993 , title=Echoes of Intra-Jewish Polemic in Paul's Letter to the Galatians , editor-last=Reinhartz , editor-first=Adele , editor-link=Adele Reinhartz , journal=Journal of Biblical Literature , publisher=Society of Biblical Literature , volume=112 , issue=3 , pages=459–477 , doi=10.2307/3267745 , issn=0021-9231 , jstor=3267745 *51 – Paul begins his second missionary journey, a trip that takes him through Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey) and on into Greece{{sfn, Walker, 1959, p=27 *50–53? Paul's second mission ({{bibleverse, , Acts, 15:36–18:22), split with Barnabas, preaches the Gospel in Galatia, Phrygia, Macedonia (Roman province), Macedonia, Philippi, Thessalonica, Beroea, Berea, Athens, Corinth, "he had his hair cut off at Cenchrea because of a vow he had taken", then returns to Antioch; First Epistle to the Thessalonians, 1 Thessalonians, Epistle to Galatians, Galatians written

Map2

*51–52 or 52–53 proconsulship of Lucius Iunius Gallio Annaeanus, Gallio according to an inscription, only fixed date in chronology of Paul *52 – Apostle Thomas, Thomas arrives in India and Saint Thomas Christians, founds an early Christian church that subsequently split into the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church and the Malankara Church (and its various descendants){{sfn, Neill, 1986, pp=44–45 *54 – Paul begins his third missionary journey{{cite web, title=Apostle Paul's Third Missionary Journey Map, website=biblestudy.org, url=http://www.biblestudy.org/maps/pauls-third-journey-map.html *53–57? Paul's third mission ({{bibleverse, , Acts, 18:23–22:30) to Galatia, Phrygia, Macedonia, Corinth, Ephesus, Greece, and Jerusalem, where James, brother of Jesus, James the Just challenged him about rumor of teaching antinomianism ({{bibleverse-nb, Acts, , 21:21), he addressed a crowd in their language (most likely Aramaic of Jesus, Aramaic); Epistle to the Romans, Romans, First Epistle to the Corinthians, 1 Corinthians, Second Epistle to the Corinthians, 2 Corinthians, Epistle to the Philippians, Philippians written

Map3

*55? "Egyptian (prophet), Egyptian prophet" (allusion to Moses) and 30,000 unarmed Jews doing the Exodus reenactment massacred by Procurator (Roman), Procurator Antonius Felix (JW2.13.5, JA20.8.6, {{bibleverse, Acts, , 21:38) *58? Paul arrested, accused of being a Zealot, revolutionary, "ringleader of the sect of the Nazarene (title), Nazarenes", teaching resurrection of the dead, imprisoned in Caesarea Maritima, Caesarea ({{bibleverse, Acts, , 23–26) *59? Paul shipwrecked on the Malta (island), island of Malta, there he was called a god ({{bibleverse, Acts, , 28:6) * 60 – Paul sent to Rome under Roman guard, evangelizes on Malta after shipwreck{{sfn, Walker, 1959, p=27 *60? Paul in Rome: greeted by many "brothers" (NRSV: "believers"), three days later called together the Jewish leaders, who hadn't received any word from Judea about him, but were curious about "this sect", which everywhere is spoken against; he tried to convince them from the "Torah, Law and Neviim, Prophets", with partial success, said the Gentiles would listen and spent two years proclaiming the Kingdom of God and teaching the "Lord Jesus Christ" ({{bibleverse, Acts, , 28:15–31); Epistle to Philemon written? *62 James the Just stoned to death for law transgression by List of High Priests of Israel, High Priest Ananus ben Artanus, popular opinion against act results in Ananus being deposed by new procurator Lucceius Albinus (JA20.9.1) *63–107? Simeon of Jerusalem, Simeon, 2nd Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem#Bishops of Jerusalem, Bishop of Jerusalem, crucified under Trajan *64–68 after July 18 Great Fire of Rome, Nero blamed and Persecution of Christians, persecuted the ''Christians'' *64/67(?)–76/79(?) Pope Linus succeeds Peter as ''Episcopus Romanus'' ("Bishop of Rome") *65? Q document, a hypothetical Greek text thought by many critical scholars to have been used in writing of Gospel of Matthew, Matthew and Gospel of Luke, Luke * 66 – Thaddeus establishes the Christian church of ArmeniaWood, Roger, Jan Morris and Denis Wright. ''Persia''. Universe Books, 1970, p. 35. *66–73 First Jewish–Roman War: destruction of Herod's Temple, Qumran community destroyed, site of Dead Sea Scrolls found in 1947 *68–107? Ignatius of Antioch, Ignatius, third Bishop of Antioch, fed to the lions in the Roman Colosseum, advocated the Bishop (Eph 6:1, Mag 2:1, 6:1, 7:1, 13:2, Tr 3:1, Smy 8:1, 9:1), rejected Sabbath in Christianity, Sabbath on Saturday in favor of The Lord's Day (Sunday). (Mag 9.1), rejected Judaizers, Judaizing (Mag 10.3), first recorded use of the term "catholic" (Smy 8:2). *69 – Saint Andrew, Andrew is crucified in Patras on the Peloponnese peninsula of Greece{{sfn, Herbermann, 1913, p=737 *70(+/−10)? Gospel of Mark, written in Rome, by Peter's interpreter (1 Peter 5:13), original ending apparently lost, endings added c. 400, see Mark 16 *70? Signs Gospel written, hypothetical Greek text used in Gospel of John to prove that Jesus is the Messiah *70–100? additional Pauline epistles *70–200? Didache; Other Gospels: Gospel of the Saviour, Gospel of Peter, Gospel of Thomas, Oxyrhynchus Gospels, Egerton Gospel, Fayyum Fragment, Dialogue of the Saviour; Jewish Christian Gospels: Gospel of the Ebionites, Gospel of the Hebrews, Gospel of the Nazarenes *76/79(?)–88 Pope Anacletus first Greek Pope, who succeeds Linus as ''Episcopus Romanus'' ("Bishop of Rome") * 80 – First Christians reported in History of Roman-era Tunisia, Tunisia and Roman Gaul, Gaul (modern-day France){{sfn, Barnett, 2002, p=23 *80(+/−20)? Gospel of Matthew, theoretically based on Mark and Q, most popular in early Christianity *80(+/−20)? Gospel of Luke, theoretically based on Mark and Q, also Acts of the Apostles by same author *88–101? Pope Clement I, Clement, fourth ''Episcopus Romanus'' ("Bishop of Rome"), wrote First Epistle of Clement, Letter of the Romans to the Corinthians (Apostolic Fathers) *90? Council of Jamnia of Judaism (disputed), Domitian applied the Fiscus Iudaicus tax even to those who merely "lived like Jews"{{cite web, url=http://jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=183&letter=F&search=Fiscus%20Iudaicus, title=Fiscus Judaicus , website=jewishencyclopedia.com *90(+/−10)? 1 Peter *94 "Testimonium Flavianum", disputed section of the ''Jewish Antiquities'' by Josephus in Aramaic language, Aramaic, translated to Koine Greek *95(+/−30)? Gospel of John and Epistles of John *95(+/−10)? Book of Revelation written, by John (son of Zebedee) and/or a disciple of his *100(+/−30)? Epistle of Barnabas (Apostolic Fathers) *100(+/−25)? Epistle of James *100(+/−10)? Epistle of Jude written, probably by doubting relative of Jesus (Mark 6:3), rejected by some early Christians due to its reference to apocryphal Book of Enoch (v14), Epistle to the Hebrews written *100 – First Christians are reported in History of Monaco#Roman rule, Monaco, Mauretania Caesariensis (modern-day Algeria), and the Anuradhapura Kingdom (modern-day Sri Lanka);{{sfn, Barnett, 2002, p=23 a missionary goes to Arbil, Arbela, old sacred city of the Assyrians.{{sfn, Latourette, 1941, loc=vol. I, p. 103 , titlestyle=background-color:lavender;

See also

{{Portal, Christianity, History, Ancient Rome, Bible {{div col, colwidth=22em * Christian martyrs * Christianity and Judaism * Christianization * Christian symbolism#Early Christian symbols * Chronological list of saints in the 1st century * Council of Jerusalem * Classical antiquity * Early centers of Christianity * Early Christian art and architecture * Hellenistic Judaism * History of Christian theology * History of Christianity * History of the Eastern Orthodox Church * History of the Catholic Church * Historiography of early Christianity * Jesuism * Mandaeism * Persecution of Christians in the New Testament * Persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire * {{section link, Spread of Christianity, Apostolic Age * Timeline of Christian missions * Timeline of Christianity * Timeline of the Catholic Church {{div col endNotes

{{Reflist, group=note, 2References