Antinazi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anti-fascism is a

Anti-fascism is a

and the

Anti-fascist movements emerged first in Italy during the rise of

Anti-fascist movements emerged first in Italy during the rise of

In Italy, Mussolini's

In Italy, Mussolini's

Clash of civilisations

, Italian Historical Society Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, p. 4 By the mid-1930s, 70,000 Slovenes had fled Italy, mostly to Slovenia (then part of Yugoslavia) and South America. The Slovene anti-fascist resistance in Yugoslavia during World War II was led by Liberation Front of the Slovenian People. The

The specific term anti-fascism was primarily used by the

The specific term anti-fascism was primarily used by the

The historian

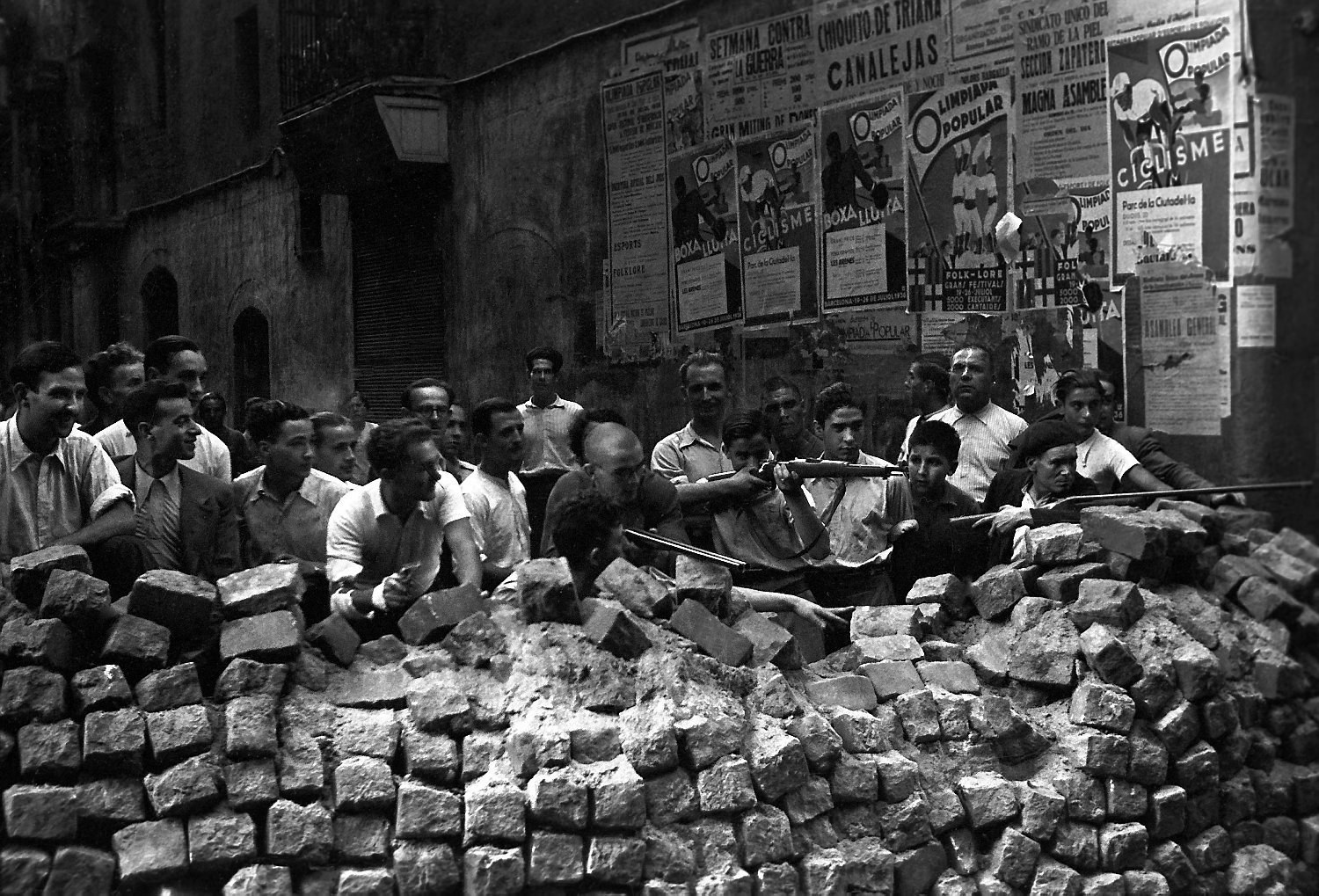

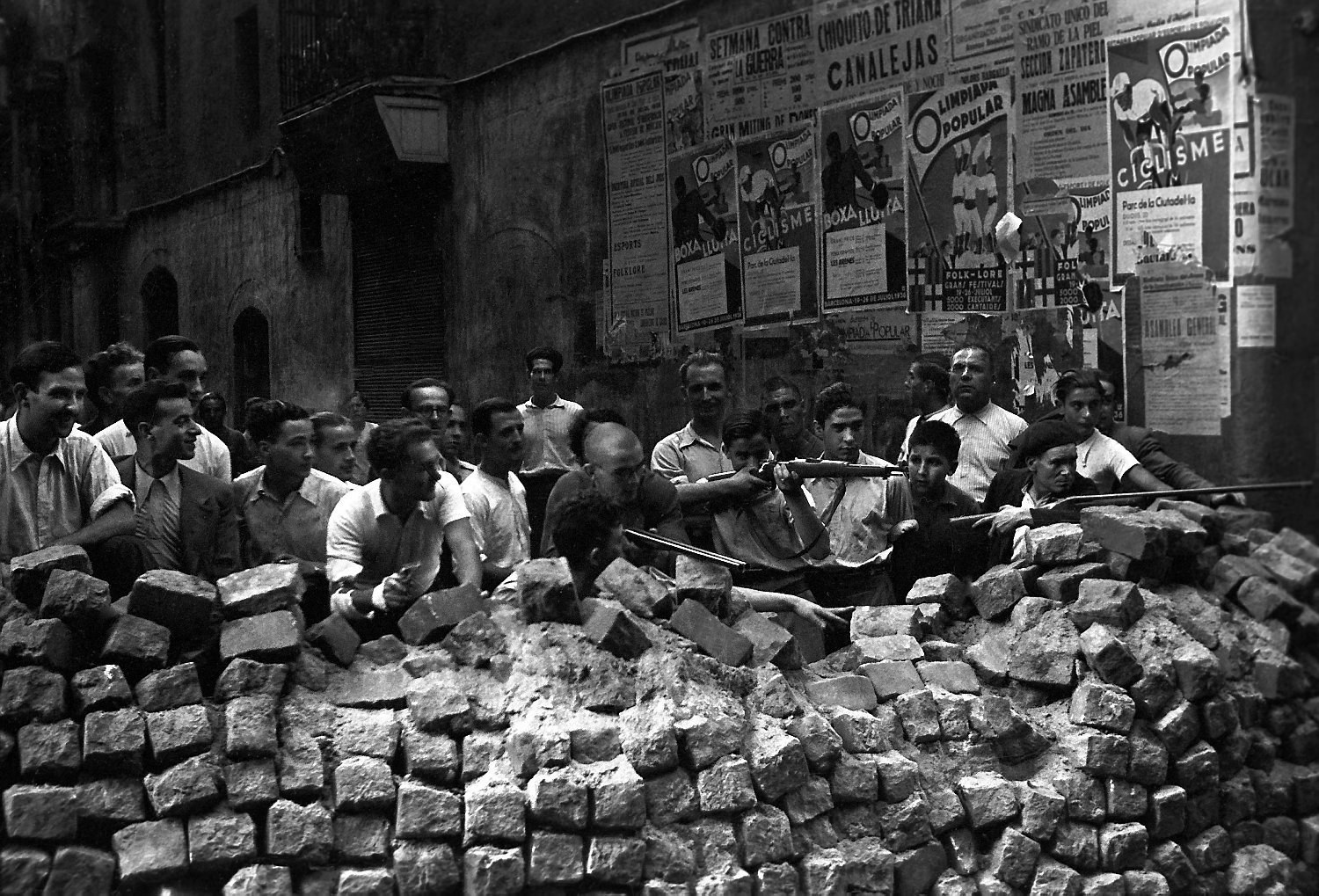

The historian  In Spain, there were histories of popular uprisings in the late 19th century through to the 1930s against the deep-seated military dictatorships. of General Prim and the Primo de la Rivieras These movements further coalesced into large-scale anti-fascist movements in the 1930s, many in the Basque Country, before and during the Spanish Civil War. The republican government and army, the

In Spain, there were histories of popular uprisings in the late 19th century through to the 1930s against the deep-seated military dictatorships. of General Prim and the Primo de la Rivieras These movements further coalesced into large-scale anti-fascist movements in the 1930s, many in the Basque Country, before and during the Spanish Civil War. The republican government and army, the

In the 1920s and 1930s in the French Third Republic, anti-fascists confronted aggressive

In the 1920s and 1930s in the French Third Republic, anti-fascists confronted aggressive

Anti-fascist Italian expatriates in the United States founded the Mazzini Society in

Anti-fascist Italian expatriates in the United States founded the Mazzini Society in

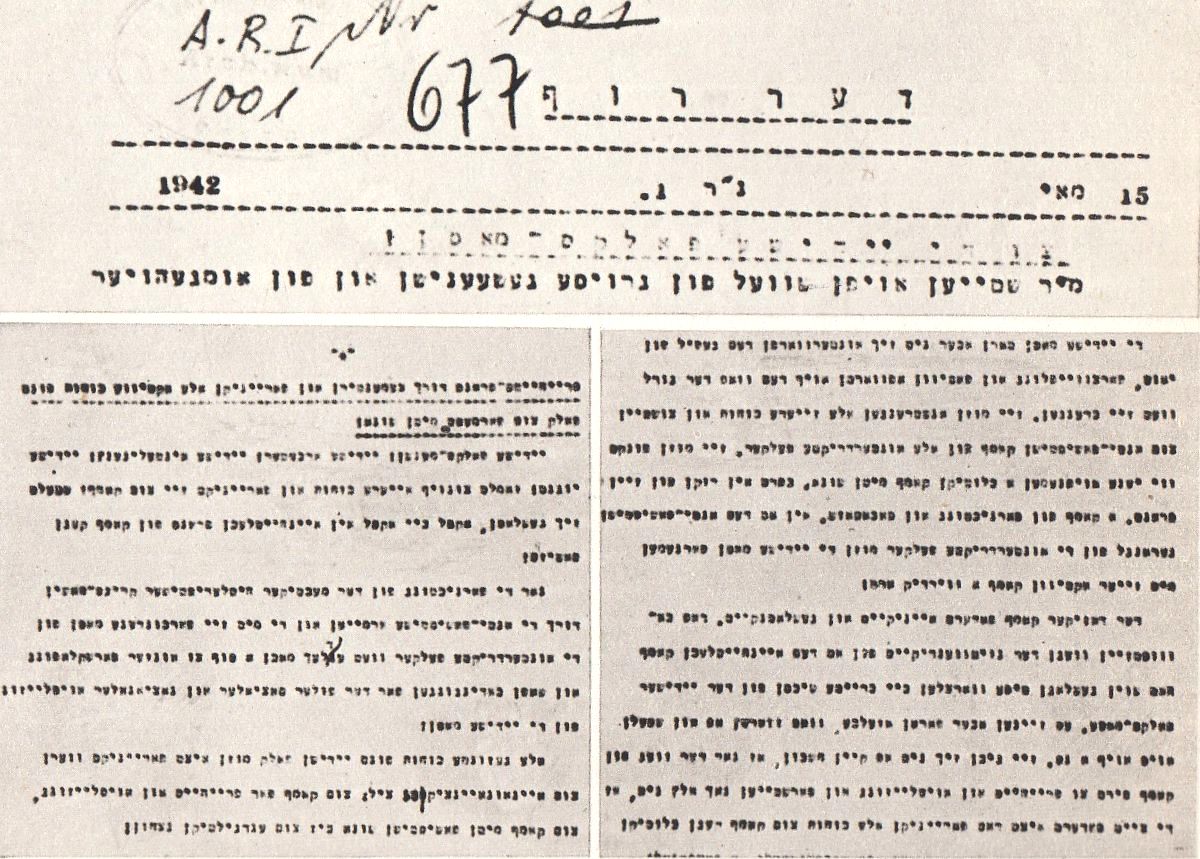

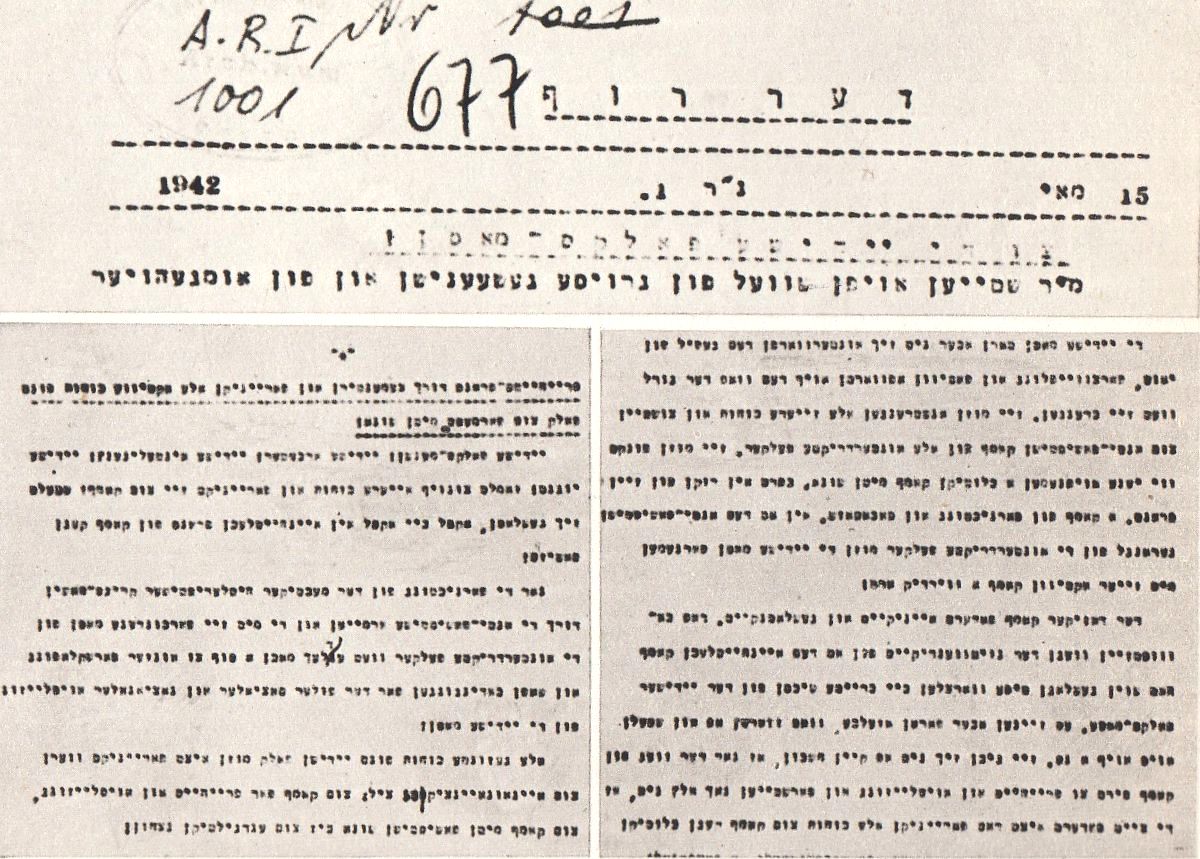

The Anti-Fascist Bloc was an organization of Polish Jews formed in the March 1942 in the Warsaw Ghetto. It was created after an alliance between leftist-Zionist, communist and socialist Jewish parties was agreed upon. The initiators of the bloc were Mordechai Anielewicz,

The Anti-Fascist Bloc was an organization of Polish Jews formed in the March 1942 in the Warsaw Ghetto. It was created after an alliance between leftist-Zionist, communist and socialist Jewish parties was agreed upon. The initiators of the bloc were Mordechai Anielewicz,

The anti-fascist movements which emerged during the period of classical fascism, both liberal and militant, continued to operate after the defeat of the Axis powers in response to the resilience and mutation of fascism both in Europe and elsewhere. In Germany, as Nazi rule crumbled in 1944, veterans of the 1930s anti-fascist struggles formed ''Antifaschistische Ausschüsse'', ''Antifaschistische Kommittees'', or '' Antifaschistische Aktion'' groups, all typically abbreviated to "antifa". The socialist government of East Germany built the

The anti-fascist movements which emerged during the period of classical fascism, both liberal and militant, continued to operate after the defeat of the Axis powers in response to the resilience and mutation of fascism both in Europe and elsewhere. In Germany, as Nazi rule crumbled in 1944, veterans of the 1930s anti-fascist struggles formed ''Antifaschistische Ausschüsse'', ''Antifaschistische Kommittees'', or '' Antifaschistische Aktion'' groups, all typically abbreviated to "antifa". The socialist government of East Germany built the

Today's Italian constitution is the result of the work of the Constituent Assembly, which was formed by the representatives of all the anti-fascist forces that contributed to the defeat of Nazi and Fascist forces during the

Today's Italian constitution is the result of the work of the Constituent Assembly, which was formed by the representatives of all the anti-fascist forces that contributed to the defeat of Nazi and Fascist forces during the  '' Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d'Italia'' (ANPI; "National Association of Italian Partisans") is an association founded by participants of the Italian resistance against the Italian Fascist regime and the subsequent Nazi occupation during World War II. ANPI was founded in Rome in 1944 while the war continued in

'' Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d'Italia'' (ANPI; "National Association of Italian Partisans") is an association founded by participants of the Italian resistance against the Italian Fascist regime and the subsequent Nazi occupation during World War II. ANPI was founded in Rome in 1944 while the war continued in

'Fascism or Revolution!' Anarchism and Antifascism in France, 1933–39

''Contemporary European History'' Volume 8, Issue 1 March 1999, pp. 51–71 * * Brasken, Kasper.

Making Anti-Fascism Transnational: The Origins of Communist and Socialist Articulations of Resistance in Europe, 1923–1924

" ''Contemporary European History'' 25.4 (2016): 573–596. * * * Class War/3WayFight/Kate Sharpley Librar

Interview from ''Beating Fascism: Anarchist Anti-Fascism in Theory and Practice''

anarkismo.net * Copsey, N. (2011) "From direct action to community action: The changing dynamics of anti-fascist opposition", in * Nigel Copsey & Andrzej Olechnowicz (eds.),

Varieties of Anti-fascism. Britain in the Inter-war Period

', Palgrave Macmillan * Gilles Dauvé

Fascism/Antifascism

, libcom.org * David Featherstone

Black Internationalism, Subaltern Cosmopolitanism, and the Spatial Politics of Antifascism

''Annals of the Association of American Geographers'' Volume 103, 2013, Issue 6, pp. 1406–1420 * Joseph Froncza

"Local People's Global Politics: A Transnational History of the Hands Off Ethiopia Movement of 1935"

''Diplomatic History'', Volume 39, Issue 2, 1 April 2015, pp. 245–274 * Hugo Garcia, ed,

Transnational Anti-Fascism: Agents, Networks, Circulations'' ''Contemporary European History

' Volume 25, Issue 4 November 2016, pp. 563–572 * * Renton, Dave.

Fascism, Anti-fascism and Britain in the 1940s

'. Springer, 2016. * * Enzo Traverso]

"Intellectuals and Anti-Fascism: For a Critical Historization"

''New Politics'', vol. 9, no. 4 (new series), whole no. 36, Winter 2004

Centre for fascist, anti-fascist and post-fascist studies

Teesside University

Remembering the Anarchist Resistance to fascism

{{DEFAULTSORT:Anti-Fascism Anti-fascism, Political movements

Anti-fascism is a

Anti-fascism is a political movement

A political movement is a collective attempt by a group of people to change government policy or social values. Political movements are usually in opposition to an element of the status quo, and are often associated with a certain ideology. Some t ...

in opposition to fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were opposed by many countries forming the Allies of World War II and dozens of resistance movements worldwide. Anti-fascism has been an element of movements across the political spectrum and holding many different political positions such as anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessa ...

, communism, pacifism, republicanism, social democracy, socialism and syndicalism as well as centrist, conservative, liberal and nationalist viewpoints.

Fascism, a far-right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

ultra-nationalistic

Ultranationalism or extreme nationalism is an Extremism, extreme form of nationalism in which a country asserts or maintains detrimental hegemony, Supremacism, supremacy, or other forms of control over other nations (usually through violent coerc ...

ideology best known for its use by the Italian Fascists and the Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

, became prominent beginning in the 1910s while organization against fascism began around 1920. Fascism became the state ideology of Italy in 1922 and of Germany in 1933, spurring a large increase in anti-fascist action, including German resistance to Nazism

Many individuals and groups in Germany that were opposed to the Nazi Germany, Nazi regime engaged in active resistance, including assassination attempts on Adolf Hitler, attempts to remove Adolf Hitler from power by assassination or by overthro ...

and the Italian resistance movement

The Italian resistance movement (the ''Resistenza italiana'' and ''la Resistenza'') is an umbrella term for the Italian resistance groups who fought the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationists of the Italian Social ...

. Anti-fascism was a major aspect of the Spanish Civil War, which foreshadowed World War II.

Prior to World War II, the West had not taken seriously the threat of fascism, and anti-fascism was sometimes associated with communism. However, the outbreak of World War II greatly changed Western perceptions, and fascism was seen as an existential threat by not only the Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

Soviet Union but also by the liberal-democratic

Liberal democracy is the combination of a liberal political ideology that operates under an indirect democratic form of government. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into diff ...

United States and United Kingdom. The Axis Powers of World War II were generally fascist, and the fight against them was characterized in anti-fascist terms. Resistance during World War II to fascism occurred in every occupied country, and came from across the ideological spectrum. The defeat of the Axis powers generally ended fascism as a state ideology.

After World War II, the anti-fascist movement continued to be active in places where organized fascism continued or re-emerged. There was a resurgence of antifa in Germany in the 1980s, as a response to the invasion of the punk scene by neo-Nazis. This influenced the antifa movement in the United States

Antifa () is a left-wing anti-fascist and anti-racist political movement in the United States. It consists of a highly decentralized array of autonomous groups that use both nonviolent direct action and violence to achieve their aims. Most an ...

in the late 1980s and 1990s, which was similarly carried by punks. In the 21st century, this greatly increased in prominence as a response to the resurgence of the radical right, especially after the election of Donald Trump

The 2016 United States presidential election was the 58th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 8, 2016. The Republican ticket of businessman Donald Trump and Indiana governor Mike Pence defeated the Democratic ticket ...

.

Origins

With the development and spread of Italian Fascism, i.e. the original fascism, the National Fascist Party's ideology was met with increasingly militant opposition by Italian communists and socialists. Organizations such as '' Arditi del Popolo''Gli Arditi del Popolo (Birth)and the

Italian Anarchist Union

The Italian Anarchist Communist Union ( it, Unione comunista anarchica italiana, UCAI), or Italian Anarchist Union ( it, Unione anarchica italiana, UAI), was an Italian political organization founded in Florence in 1919. It played an important role ...

emerged between 1919 and 1921, to combat the nationalist and fascist surge of the post-World War I period.

In the words of historian Eric Hobsbawm

Eric John Ernest Hobsbawm (; 9 June 1917 – 1 October 2012) was a British historian of the rise of industrial capitalism, socialism and nationalism. A life-long Marxist, his socio-political convictions influenced the character of his work. H ...

, as fascism developed and spread, a "nationalism of the left" developed in those nations threatened by Italian irredentism (e.g. in the Balkans, and Albania in particular). After the outbreak of World War II, the Albanian

Albanian may refer to:

*Pertaining to Albania in Southeast Europe; in particular:

**Albanians, an ethnic group native to the Balkans

**Albanian language

**Albanian culture

**Demographics of Albania, includes other ethnic groups within the country ...

and Yugoslav resistances were instrumental in antifascist action and underground resistance. This combination of irreconcilable nationalisms and leftist

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

partisans constitute the earliest roots of European anti-fascism. Less militant forms of anti-fascism arose later. During the 1930s in Britain, "Christians – especially the Church of England – provided both a language of opposition to fascism and inspired anti-fascist action".

Michael Seidman argues that traditionally anti-fascism was seen as the purview of the political left but that in recent years this has been questioned. Seidman identifies two types of anti-fascism, namely revolutionary and counterrevolutionary:

* Revolutionary anti-fascism was expressed amongst communists and anarchists, where it identified fascism and capitalism as its enemies and made little distinction between fascism and other forms of authoritarianism. It did not disappear after the Second World War but was used as an official ideology of the Soviet bloc, with the "fascist" West as the new enemy.

* Counterrevolutionary anti-fascism was much more conservative in nature, with Seidman arguing that Charles de Gaulle and Winston Churchill represented examples of it and that they tried to win the masses to their cause. Counterrevolutionary antifascists desired to ensure the restoration or continuation of the prewar old regime and conservative antifascists disliked fascism's erasure of the distinction between the public and private spheres. Like its revolutionary counterpart, it would outlast fascism once the Second World War ended.

Seidman argues that despite the differences between these two strands of anti-fascism, there were similarities. They would both come to regard violent expansion as intrinsic to the fascist project. They both rejected any claim that the Versailles Treaty was responsible for the rise of Nazism and instead viewed fascist dynamism as the cause of conflict. Unlike fascism, these two types of anti-fascism did not promise a quick victory but an extended struggle against a powerful enemy. During World War II, both anti-fascisms responded to fascist aggression by creating a cult of heroism which relegated victims to a secondary position.Seidman, Michael. Transatlantic Antifascisms: From the Spanish Civil War to the End of World War II. Cambridge University Press, 2017, pp.1-8 However, after the war, conflict arose between the revolutionary and counterrevolutionary anti-fascisms; the victory of the Western Allies allowed them to restore the old regimes of liberal democracy in Western Europe, while Soviet victory in Eastern Europe allowed for the establishment of new revolutionary anti-fascist regimes there.

History

Anti-fascist movements emerged first in Italy during the rise of

Anti-fascist movements emerged first in Italy during the rise of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

, but they soon spread to other European countries and then globally. In the early period, Communist, socialist, anarchist and Christian workers and intellectuals were involved. Until 1928, the period of the United front, there was significant collaboration between the Communists and non-Communist anti-fascists.

In 1928, the Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet Union, Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to ...

instituted its ultra-left Third Period policies, ending co-operation with other left groups, and denouncing social democrats as " social fascists". From 1934 until the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, the Communists pursued a Popular Front approach, of building broad-based coalitions with liberal and even conservative anti-fascists. As fascism consolidated its power, and especially during World War II, anti-fascism largely took the form of partisan

Partisan may refer to:

Military

* Partisan (weapon), a pole weapon

* Partisan (military), paramilitary forces engaged behind the front line

Films

* ''Partisan'' (film), a 2015 Australian film

* ''Hell River'', a 1974 Yugoslavian film also know ...

or resistance

Resistance may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Comics

* Either of two similarly named but otherwise unrelated comic book series, both published by Wildstorm:

** ''Resistance'' (comics), based on the video game of the same title

** ''T ...

movements.

Italy: against Fascism and Mussolini

Fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

regime used the term ''anti-fascist'' to describe its opponents. Mussolini's secret police was officially known as the Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism. During the 1920s in the Kingdom of Italy, anti-fascists, many of them from the labor movement

The labour movement or labor movement consists of two main wings: the trade union movement (British English) or labor union movement (American English) on the one hand, and the political labour movement on the other.

* The trade union movement ...

, fought against the violent Blackshirts and against the rise of the fascist leader Benito Mussolini. After the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) signed a pacification pact with Mussolini and his Fasces of Combat on 3 August 1921, and trade unions adopted a legalist and pacified strategy, members of the workers' movement who disagreed with this strategy formed '' Arditi del Popolo''.

The Italian General Confederation of Labour (CGL) and the PSI refused to officially recognize the anti-fascist militia and maintained a non-violent, legalist strategy, while the Communist Party of Italy

The Italian Communist Party ( it, Partito Comunista Italiano, PCI) was a communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current ...

(PCd'I) ordered its members to quit the organization. The PCd'I organized some militant groups, but their actions were relatively minor. The Italian anarchist Severino Di Giovanni, who exiled himself to Argentina following the 1922 March on Rome, organized several bombings against the Italian fascist community. The Italian liberal anti-fascist Benedetto Croce

Benedetto Croce (; 25 February 1866 – 20 November 1952)

was an Italian idealist philosopher, historian, and politician, who wrote on numerous topics, including philosophy, history, historiography and aesthetics. In most regards, Croce was a lib ...

wrote his '' Manifesto of the Anti-Fascist Intellectuals'', which was published in 1925. Other notable Italian liberal anti-fascists around that time were Piero Gobetti and Carlo Rosselli

Carlo Alberto Rosselli (Rome, 16 November 1899Bagnoles-de-l'Orne, 9 June 1937) was an Italian political leader, journalist, historian, philosopher and anti-fascist activist, first in Italy and then abroad. He developed a theory of reformist, ...

.

Concentrazione Antifascista Italiana

(CAI; Italian Anti-Fascist Concentration), officially known as (Anti-Fascist Action Concentration), was an Italian coalition of anti-fascist groups which existed from 1927 to 1934. It was formed in Paris on 27 March 1927 with the purpose of the ...

(Italian Anti-Fascist Concentration), officially known as Concentrazione d'Azione Antifascista (Anti-Fascist Action Concentration), was an Italian coalition of Anti-Fascist groups which existed from 1927 to 1934. Founded in Nérac

Nérac (; oc, Nerac, ) is a commune in the Lot-et-Garonne department, Southwestern France. The composer and organist Louis Raffy was born in Nérac, as was the former Arsenal and Bordeaux footballer Marouane Chamakh, as was Admiral Francois Dar ...

, France, by expatriate Italians, the CAI was an alliance of non-communist anti-fascist forces (republican, socialist, nationalist) trying to promote and to coordinate expatriate actions to fight fascism in Italy; they published a propaganda paper entitled ''La Libertà''.

Between 1920 and 1943, several anti-fascist movements were active among the Slovenes and Croats in the territories annexed to Italy after World War I, known as the Julian March. The most influential was the militant insurgent organization TIGR, which carried out numerous sabotages, as well as attacks on representatives of the Fascist Party and the military. Most of the underground structure of the organization was discovered and dismantled by the Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism (OVRA) in 1940 and 1941, and after June 1941 most of its former activists joined the Slovene Partisans.

During World War II, many members of the Italian resistance left their homes and went to live in the mountains, fighting against Italian fascists and German Nazi

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

soldiers during the Italian Civil War

The Italian Civil War (Italian language, Italian: ''Guerra civile italiana'', ) was a civil war in the Kingdom of Italy fought during World War II by Italian Fascists against the Italian resistance movement, Italian partisans (mostly politically ...

. Many cities in Italy, including Turin, Naples and Milan, were freed by anti-fascist uprisings.

Slovenians and Croats under Italianization

The anti-fascist resistance emerged within theSlovene minority in Italy (1920–1947)

The Slovene minority in Italy (1920–1947) was the indigenous Slovene population—approximately 327,000 out of a total population of 1.3Lipušček, U. (2012) ''Sacro egoismo: Slovenci v krempljih tajnega londonskega pakta 1915'', Cankarjeva zalo ...

, whom the Fascists meant to deprive of their culture, language and ethnicity. The 1920 burning of the National Hall in Trieste, the Slovene center in the multi-cultural and multi-ethnic Trieste by the Blackshirts, was praised by Benito Mussolini (yet to become Il Duce) as a "masterpiece of the Triestine fascism" (). The use of Slovene in public places, including churches, was forbidden, not only in multi-ethnic areas, but also in the areas where the population was exclusively Slovene. Children, if they spoke Slovene, were punished by Italian teachers who were brought by the Fascist State from Southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the peop ...

. Slovene teachers, writers, and clergy were sent to the other side of Italy.

The first anti-fascist organization, called TIGR, was formed by Slovenes and Croats in 1927 in order to fight Fascist violence. Its guerrilla fight continued into the late 1920s and 1930s.Cresciani, Gianfranco (2004Clash of civilisations

, Italian Historical Society Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, p. 4 By the mid-1930s, 70,000 Slovenes had fled Italy, mostly to Slovenia (then part of Yugoslavia) and South America. The Slovene anti-fascist resistance in Yugoslavia during World War II was led by Liberation Front of the Slovenian People. The

Province of Ljubljana The Province of Ljubljana ( it, Provincia di Lubiana, sl, Ljubljanska pokrajina, german: Provinz Laibach) was the central-southern area of Slovenia. In 1941, it was annexed by Fascist Italy, and after 1943 occupied by Nazi Germany. Created on May ...

, occupied by Italian Fascists, saw the deportation of 25,000 people, representing 7.5% of the total population, filling up the Rab concentration camp and Gonars concentration camp as well as other Italian concentration camps

Italian concentration camps include camps from the Italian colonial wars in Africa as well as camps for the civilian population from areas occupied by Italy during World War II. Memory of both camps were subjected to "historical amnesia". The repr ...

.

Germany: against the NSDAP and Hitlerism

The specific term anti-fascism was primarily used by the

The specific term anti-fascism was primarily used by the Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany (german: Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, , KPD ) was a major political party in the Weimar Republic between 1918 and 1933, an underground resistance movement in Nazi Germany, and a minor party in West German ...

(KPD), which held the view that it was the only anti-fascist party in Germany. The KPD formed several explicitly anti-fascist groups such as ''Roter Frontkämpferbund

The (, translated as "Alliance of Red Front-Fighters" or "Red Front Fighters' League"), usually called (RFB), was a far-left paramilitary organization affiliated with the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) during the Weimar Republic. It was off ...

'' (formed in 1924 and banned by the Social Democrats in 1929) and ''Kampfbund gegen den Faschismus'' (a ''de facto'' successor to the latter). At its height, ''Roter Frontkämpferbund'' had over 100,000 members. In 1932, the KPD established the Antifaschistische Aktion as a "red united front under the leadership of the only anti-fascist party, the KPD". Under the leadership of the committed Stalinist

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory o ...

Ernst Thälmann, the KPD primarily viewed fascism as the final stage of capitalism rather than as a specific movement or group, and therefore applied the term broadly to its opponents, and in the name of anti-fascism the KPD focused in large part on attacking its main adversary, the centre-left Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (german: Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, ; SPD, ) is a centre-left social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany.

Saskia Esken has been the ...

, whom they referred to as social fascists and regarded as the "main pillar of the dictatorship of Capital."

The movement of Nazism, which grew ever more influential in the last years of the Weimar Republic, was opposed for different ideological reasons by a wide variety of groups, including groups which also opposed each other, such as social democrats, centrists, conservatives and communists. The SPD and centrists formed ''Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold

The (, ''"Black, Red, ndGold Banner of the Reich"'') was an organization in Germany during the Weimar Republic, formed by members of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), the German Centre Party, and the (liberal) German Democratic Par ...

'' in 1924 to defend liberal democracy against both the Nazi Party and the KPD, and their affiliated organizations. Later, mainly SPD members formed the Iron Front which opposed the same groups.

The name and logo of ''Antifaschistische Aktion'' remain influential. Its two-flag logo, designed by and , is still widely used as a symbol of militant anti-fascists in Germany and globally, as is the Iron Front's Three Arrows logo.

Spain: Civil War against the Nationalists

The historian

The historian Eric Hobsbawm

Eric John Ernest Hobsbawm (; 9 June 1917 – 1 October 2012) was a British historian of the rise of industrial capitalism, socialism and nationalism. A life-long Marxist, his socio-political convictions influenced the character of his work. H ...

wrote: "The Spanish civil war was both at the centre and on the margin of the era of anti-fascism. It was central, since it was immediately seen as a European war between fascism and anti-fascism, almost as the first battle in the coming world war, some of the characteristic aspects of which – for example, air raids against civilian populations – it anticipated."

In Spain, there were histories of popular uprisings in the late 19th century through to the 1930s against the deep-seated military dictatorships. of General Prim and the Primo de la Rivieras These movements further coalesced into large-scale anti-fascist movements in the 1930s, many in the Basque Country, before and during the Spanish Civil War. The republican government and army, the

In Spain, there were histories of popular uprisings in the late 19th century through to the 1930s against the deep-seated military dictatorships. of General Prim and the Primo de la Rivieras These movements further coalesced into large-scale anti-fascist movements in the 1930s, many in the Basque Country, before and during the Spanish Civil War. The republican government and army, the Antifascist Worker and Peasant Militias

{{anti-fascism sidebar, Interwar anti-fascism

The Antifascist Worker and Peasant Militias ( es, Milicias Antifascistas Obreras y Campesinas, MAOC) were a militia group founded in the Second Spanish Republic in 1934. Their purpose was to protect l ...

(MAOC) linked to the Communist Party (PCE),De Miguel, Jesús y Sánchez, Antonio: ''Batalla de Madrid,'' in his ''Historia Ilustrada de la Guerra Civil Española.'' Alcobendas, Editorial Libsa, 2006, pp. 189–221. the International Brigades

The International Brigades ( es, Brigadas Internacionales) were military units set up by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The organization existed f ...

, the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), Spanish anarchist

Anarchism in Spain has historically gained some support and influence, especially before Francisco Franco's victory in the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939, when it played an active political role and is considered the end of the golden age of cl ...

militias, such as the Iron Column

The Iron Column ( ca, Columna de Ferro, es, Columna de Hierro) was a Valencian anarchist militia column formed during the Spanish Civil War to fight against the military forces of the Nationalist Faction that had rebelled against the Second ...

and the autonomous governments of Catalonia and the Basque Country

Basque Country may refer to:

* Basque Country (autonomous community), as used in Spain ( es, País Vasco, link=no), also called , an Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain (shown in pink on the map)

* French Basque Country o ...

, fought the rise of Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

with military force.

The Friends of Durruti

The Friends of Durruti Group (in Spanish, ''Agrupación de los Amigos de Durruti'') was an anarchist group in Spain, named after Buenaventura Durruti. It was founded on 15 March 1937, by Jaime Balius, Félix Martínez (anarchist), Félix Martínez ...

, associated with the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI), were a particularly militant group. Thousands of people from many countries went to Spain in support of the anti-fascist cause, joining units such as the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, the British Battalion, the Dabrowski Battalion

The Dabrowski Battalion, also known as Dąbrowszczacy (), was a battalion of the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. It was initially formed entirely of volunteers, "chiefly composed of Polish miners recently living and working in F ...

, the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, the Naftali Botwin Company

According to the Book of Genesis, Naphtali (; ) was the last of the two sons of Jacob and Bilhah (Jacob's sixth son). He was the founder of the Israelite Tribe of Naphtali.

Some biblical commentators have suggested that the name ''Naphtali'' ma ...

and the Thälmann Battalion

The Thälmann Battalion was a battalion of the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. It was named after the imprisoned German communist leader Ernst Thälmann (born 16 April 1886, executed 18 August 1944) and included approximately 1,50 ...

, including Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

's nephew, Esmond Romilly

}

Esmond Marcus David Romilly (10 June 1918 – 30 November 1941) was a British socialist, anti-fascist, and journalist, who was in turn a schoolboy rebel, a veteran with the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War and, following ...

. Notable anti-fascists who worked internationally against Franco included: George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalitar ...

(who fought in the POUM militia and wrote '' Homage to Catalonia'' about his experience), Ernest Hemingway (a supporter of the International Brigades who wrote '' For Whom the Bell Tolls'' about his experience), and the radical journalist Martha Gellhorn.

The Spanish anarchist guerrilla Francesc Sabaté Llopart fought against Franco's regime until the 1960s, from a base in France. The Spanish Maquis, linked to the PCE, also fought the Franco regime long after the Spanish Civil war had ended.

France: against ''Action Française'' and Vichy

In the 1920s and 1930s in the French Third Republic, anti-fascists confronted aggressive

In the 1920s and 1930s in the French Third Republic, anti-fascists confronted aggressive far-right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

groups such as the Action Française movement in France, which dominated the Latin Quarter students' neighborhood. After fascism triumphed via invasion, the French Resistance (french: La Résistance française) or, more accurately, resistance movements fought against the Nazi German occupation and against the collaborationist Vichy régime. Resistance cells were small groups of armed men and women (called the ''maquis'' in rural areas), who, in addition to their guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or Irregular military, irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, Raid (military), raids ...

activities, were also publishers of underground newspapers and magazines such as '' Arbeiter und Soldat'' (''Worker and Soldier'') during World War Two, providers of first-hand intelligence information, and maintainers of escape networks.

United Kingdom: against Mosley's BUF

The rise of Oswald Mosley'sBritish Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, fo ...

(BUF) in the 1930s was challenged by the Communist Party of Great Britain

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was the largest communist organisation in Britain and was founded in 1920 through a merger of several smaller Marxist groups. Many miners joined the CPGB in the 1926 general strike. In 1930, the CPG ...

, socialists in the Labour Party and Independent Labour Party, anarchists, Irish Catholic dockmen and working class Jews in London's East End

The East End of London, often referred to within the London area simply as the East End, is the historic core of wider East London, east of the Roman and medieval walls of the City of London and north of the River Thames. It does not have uni ...

. A high point in the struggle was the Battle of Cable Street, when thousands of eastenders and others turned out to stop the BUF from marching. Initially, the national Communist Party leadership wanted a mass demonstration at Hyde Park

Hyde Park may refer to:

Places

England

* Hyde Park, London, a Royal Park in Central London

* Hyde Park, Leeds, an inner-city area of north-west Leeds

* Hyde Park, Sheffield, district of Sheffield

* Hyde Park, in Hyde, Greater Manchester

Austra ...

in solidarity with Republican Spain, instead of a mobilization against the BUF, but local party activists argued against this. Activists rallied support with the slogan ''They shall not pass

In Modern English, ''they'' is a third-person pronoun relating to a grammatical subject.

Morphology

In Standard Modern English, ''they'' has five distinct word forms:

* ''they'': the nominative (subjective) form

* ''them'': the accusati ...

,'' adopted from Republican Spain.

There were debates within the anti-fascist movement over tactics. While many East End ex-servicemen participated in violence against fascists, Communist Party leader Phil Piratin

Philip Piratin (15 May 1907 – 10 December 1995) was a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) and one of the four CPGB Members of Parliament during the first thirty years of its existence. (The others were Shapurji Saklatvala, Wa ...

denounced these tactics and instead called for large demonstrations. In addition to the militant anti-fascist movement, there was a smaller current of liberal anti-fascism in Britain; Sir Ernest Barker

Sir Ernest Barker (23 September 1874 – 17 February 1960) was an English political scientist who served as Principal of King's College London from 1920 to 1927.

Life and career

Ernest Barker was born in Woodley, Cheshire, and educated at Ma ...

, for example, was a notable English liberal anti-fascist in the 1930s.

United States, World War II

Anti-fascist Italian expatriates in the United States founded the Mazzini Society in

Anti-fascist Italian expatriates in the United States founded the Mazzini Society in Northampton, Massachusetts

The city of Northampton is the county seat of Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of Northampton (including its outer villages, Florence and Leeds) was 29,571.

Northampton is known as an acade ...

in September 1939 to work toward ending Fascist rule in Italy. As political refugees from Mussolini's regime, they disagreed among themselves whether to ally with Communists and anarchists or to exclude them. The Mazzini Society joined with other anti-Fascist Italian expatriates in the Americas at a conference in Montevideo

Montevideo () is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Uruguay, largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2011 census, the city proper has a population of 1,319,108 (about one-third of the country's total population) in an area of . M ...

, Uruguay in 1942. They unsuccessfully promoted one of their members, Carlo Sforza, to become the post-Fascist leader of a republican Italy. The Mazzini Society dispersed after the overthrow of Mussolini as most of its members returned to Italy.

During the Second Red Scare which occurred in the United States in the years that immediately followed the end of World War II, the term "premature anti-fascist" came into currency and it was used to describe Americans who had strongly agitated or worked against fascism, such as Americans who had fought for the Republicans

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

during the Spanish Civil War, before fascism was seen as a proximate and existential threat to the United States (which only occurred generally after the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany and only occurred universally after the attack on Pearl Harbor). The implication was that such persons were either Communists or Communist sympathizers whose loyalty to the United States was suspect. However, the historians John Earl Haynes

John Earl Haynes (born 1944) is an American historian who worked as a specialist in 20th-century political history in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress. He is known for his books on the subject of the American Communist and anti- ...

and Harvey Klehr have written that no documentary evidence has been found of the US government referring to American members of the International Brigades

The International Brigades ( es, Brigadas Internacionales) were military units set up by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The organization existed f ...

as "premature antifascists": the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

, Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the intelligence agency of the United States during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines for all branc ...

, and United States Army records used terms such as "Communist", "Red", "subversive", and "radical" instead. Indeed, Haynes and Klehr indicate that they have found many examples of members of the XV International Brigade and their supporters referring to themselves sardonically as "premature antifascists".

Burma, World War II

TheAnti-Fascist Organisation

The Anti-Fascist Organisation (AFO) was a resistance movement against the Japanese occupation of Burma and independence of Burma during World War II. It was the forerunner of the Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League.

History

The AFO was formed a ...

(AFO) was a resistance movement which advocated the independence of Burma and fought against the Japanese occupation of Burma

The Japanese occupation of Burma was the period between 1942 and 1945 during World War II, when Burma was occupied by the Empire of Japan. The Japanese had assisted formation of the Burma Independence Army, and trained the Thirty Comrades, who ...

during World War II. It was the forerunner of the Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League. The AFO was formed during a meeting which was held in Pegu in August 1944, the meeting was held by the leaders of the Communist Party of Burma (CPB), the Burma National Army (BNA) led by General Aung San, and the People's Revolutionary Party (PRP), later renamed the Burma Socialist Party

The Burma Socialist Party (), initially known as the People's Freedom (Socialist) Party or PF(S)P, was a political party in Burma. It was the dominant party in Burmese politics after 1948, and the dominant political force inside the Anti-Fascist ...

. Whilst in Insein prison in July 1941, CPB leaders Thakin Than Tun

Thakin Than Tun ( my, သခင် သန်းထွန်း; 1911 – 24 September 1968) was a Burmese politician and leader of the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) from 1945 until his assassination in 1968. He was uncle of the former State C ...

and Thakin Soe

Thakin Soe ( my, သခင်စိုး, ; 1906 – 6 May 1989) was a founding member of the Communist Party of Burma, formed in 1939 and a leader of Anti-Fascist Organisation. He is regarded as one of Burma's most prominent communist leaders. ...

had co-authored the ''Insein Manifesto'', which, against the prevailing opinion in the Burmese nationalist movement led by the ''Dobama Asiayone

Dobama Asiayone ( my, တို့ဗမာအစည်းအရုံး, ''Dóbăma Ăsì-Ăyòun'', meaning ''We Burmans Association'', DAA), commonly known as the Thakhins ( my, သခင် ''sa.hkang'', lit. Lords), was a Burmese national ...

'', identified world fascism as the main enemy in the coming war and called for temporary cooperation with the British in a broad allied coalition that included the Soviet Union. Soe had already gone underground to organise resistance against the Japanese occupation, and Than Tun as Minister of Land and Agriculture was able to pass on Japanese intelligence to Soe, while other Communist leaders Thakin Thein Pe and Thakin Tin Shwe made contact with the exiled colonial government in Simla, India. Aung San was War Minister in the puppet administration which was set up on 1 August 1943 and included the Socialist leaders Thakin Nu and Thakin Mya

Dobama Asiayone ( my, တို့ဗမာအစည်းအရုံး, ''Dóbăma Ăsì-Ăyòun'', meaning ''We Burmans Association'', DAA), commonly known as the Thakhins ( my, သခင် ''sa.hkang'', lit. Lords), was a Burmese national ...

. During a meeting which was held between 1 and 3 March 1945, the AFO was reorganized as a multi-party front which was named the Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League.

Poland, World War II

The Anti-Fascist Bloc was an organization of Polish Jews formed in the March 1942 in the Warsaw Ghetto. It was created after an alliance between leftist-Zionist, communist and socialist Jewish parties was agreed upon. The initiators of the bloc were Mordechai Anielewicz,

The Anti-Fascist Bloc was an organization of Polish Jews formed in the March 1942 in the Warsaw Ghetto. It was created after an alliance between leftist-Zionist, communist and socialist Jewish parties was agreed upon. The initiators of the bloc were Mordechai Anielewicz, Józef Lewartowski

Józef Lewartowski ( yi, יוסף לעווארטאווסקי, birth name: Aron Finkelstein yi, ןאהרן פינקעלשטיי May 1895 Bielsk Podlaski - 25 August 1942 Warsaw) was a Polish communist politician of Jewish origin, revolutionary, ...

(Aron Finkelstein) from the Polish Workers' Party, Josef Kaplan Josef may refer to

*Josef (given name)

*Josef (surname)

*Josef (film), ''Josef'' (film), a 2011 Croatian war film

*Musik Josef, a Japanese manufacturer of musical instruments

{{disambiguation ...

from Hashomer Hatzair

Hashomer Hatzair ( he, הַשׁוֹמֵר הַצָעִיר, , ''The Young Guard'') is a Labor Zionist, secular Jewish youth movement founded in 1913 in the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, Austria-Hungary, and it was also the name of the group ...

, Szachno Sagan from Poale Zion-Left, Jozef Sak

Jozef or Józef is a Dutch, Breton, Polish and Slovak version of masculine given name Joseph. A selection of people with that name follows. For a comprehensive list see and ..

* Józef Beck (1894–1944), Polish foreign minister in the 1930s

* ...

as a representative of socialist-Zionists and Izaak Cukierman

Yitzhak Zuckerman ( pl, Icchak Cukierman; he, יצחק צוקרמן; 13 December 1915 – 17 June 1981), also known by his nom de guerre "Antek", was one of the leaders of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943 against Nazi Germany during World Wa ...

with his wife Cywia Lubetkin

Zivia Lubetkin ( pl, Cywia Lubetkin, , he, צביה לובטקין, nom de guerre: Celina; 9 November 1914 – 11 July 1978) was one of the leaders of the Jewish underground in Nazi-occupied Warsaw and the only woman on the High Command of the ...

from Dror. The Jewish Bund

The General Jewish Labour Bund in Lithuania, Poland and Russia ( yi, אַלגעמײנער ייִדישער אַרבעטער־בונד אין ליטע, פּױלן און רוסלאַנד , translit=Algemeyner Yidisher Arbeter-bund in Lite, Poy ...

did not join the bloc though they were represented at its first conference by Abraham Blum

Abraham Blum (also known as Abrasza Blum; born c. 1905, Wilno (now Vilnius) – May 1943, Warsaw) was a Polish-Jewish socialist activist, one of the leaders of the Bund in the Warsaw Ghetto and a participant in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

Ear ...

and Maurycy Orzech.

After World War II

The anti-fascist movements which emerged during the period of classical fascism, both liberal and militant, continued to operate after the defeat of the Axis powers in response to the resilience and mutation of fascism both in Europe and elsewhere. In Germany, as Nazi rule crumbled in 1944, veterans of the 1930s anti-fascist struggles formed ''Antifaschistische Ausschüsse'', ''Antifaschistische Kommittees'', or '' Antifaschistische Aktion'' groups, all typically abbreviated to "antifa". The socialist government of East Germany built the

The anti-fascist movements which emerged during the period of classical fascism, both liberal and militant, continued to operate after the defeat of the Axis powers in response to the resilience and mutation of fascism both in Europe and elsewhere. In Germany, as Nazi rule crumbled in 1944, veterans of the 1930s anti-fascist struggles formed ''Antifaschistische Ausschüsse'', ''Antifaschistische Kommittees'', or '' Antifaschistische Aktion'' groups, all typically abbreviated to "antifa". The socialist government of East Germany built the Berlin Wall

The Berlin Wall (german: Berliner Mauer, ) was a guarded concrete barrier that encircled West Berlin from 1961 to 1989, separating it from East Berlin and East Germany (GDR). Construction of the Berlin Wall was commenced by the government ...

in 1961, and the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

referred to it officially as the "Anti-fascist Protection Rampart". Resistance to fascists dictatorships in Spain and Portugal continued, including the activities of the Spanish Maquis and others, leading up to the Spanish transition to democracy

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Cana ...

and the Carnation Revolution

The Carnation Revolution ( pt, Revolução dos Cravos), also known as the 25 April ( pt, 25 de Abril, links=no), was a military coup by left-leaning military officers that overthrew the authoritarian Estado Novo regime on 25 April 1974 in Lisbo ...

, respectively, as well as to similar dictatorships in Chile and elsewhere. Other notable anti-fascist mobilisations in the first decades of the post-war period include the 43 Group

The 43 Group was an English anti-fascist group set up by Jewish ex-servicemen after the Second World War. They did this when, upon returning to London, they encountered British fascist organisations such as Jeffrey Hamm's British League of Ex- ...

in Britain.

With the start of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

between the former World War II allies of the United States and the Soviet Union, the concept of totalitarianism became prominent in Western anti-communist

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, w ...

political discourse as a tool to convert pre-war anti-fascism into post-war anti-communism.Siegel, Achim (1998). ''The Totalitarian Paradigm after the End of Communism: Towards a Theoretical Reassessment''. Rodopi. p. 200. . "Concepts of totalitarianism became most widespread at the height of the Cold War. Since the late 1940s, especially since the Korean War, they were condensed into a far-reaching, even hegemonic, ideology, by which the political elites of the Western world tried to explain and even to justify the Cold War constellation."Guilhot, Nicholas (2005). ''The Democracy Makers: Human Rights and International Order''. Columbia University Press. p. 33. . "The opposition between the West and Soviet totalitarianism was often presented as an opposition both moral and epistemological between truth and falsehood. The democratic, social, and economic credentials of the Soviet Union were typically seen as 'lies' and as the product of a deliberate and multiform propaganda. ..In this context, the concept of totalitarianism was itself an asset. As it made possible the conversion of prewar anti-fascism into postwar anti-communism."Reisch, George A. (2005). ''How the Cold War Transformed Philosophy of Science: To the Icy Slopes of Logic''. Cambridge University Press. pp. 153–154. .

Modern antifa politics can be traced to opposition to the infiltration of Britain's punk scene by white power skinheads

White power skinheads, also known as racist skinheads and neo-Nazi skinheads, are members of a neo-Nazi, white supremacist and antisemitic offshoot of the skinhead subculture. Many of them are affiliated with white nationalist organizations an ...

in the 1970s and 1980s, and the emergence of neo-Nazism

Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazism, Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and Supremacism#Racial, racial supremacy (ofte ...

in Germany following the fall of the Berlin Wall. In Germany, young leftists, including anarchists and punk fans, renewed the practice of street-level anti-fascism. Columnist Peter Beinart writes that "in the late '80s, left-wing punk fans in the United States began following suit, though they initially called their groups Anti-Racist Action (ARA) on the theory that Americans would be more familiar with fighting racism than they would be with fighting fascism".

Germany

The contemporary antifa movement in Germany comprises different anti-fascist groups which usually use the abbreviation antifa and regard the historical '' Antifaschistische Aktion'' (Antifa) of the early 1930s as an inspiration, drawing on the historic group for its aesthetics and some of its tactics, in addition to the name. Many new antifa groups formed from the late 1980s onward. According to Loren Balhorn, contemporary antifa in Germany "has no practical historical connection to the movement from which it takes its name but is instead a product of West Germany's squatter scene and autonomist movement in the 1980s". One of the biggest antifascist campaigns in Germany in recent years was the ultimately successful effort to block the annual Nazi-rallies in the east German city of Dresden in Saxony which had grown into "Europe's biggest gathering of Nazis". Unlike the original Antifa which had links to theCommunist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany (german: Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, , KPD ) was a major political party in the Weimar Republic between 1918 and 1933, an underground resistance movement in Nazi Germany, and a minor party in West German ...

and which was concerned with industrial working-class politics, the late 1980s and early 1990s, autonomists

The Autonomists (french: Autonomistes; it, Autonomisti) was a Christian-democratic Italian political party active in the Aosta Valley.

It was founded in 1997 by the union of the regional Italian People's Party with For Aosta Valley, and some f ...

were independent anti-authoritarian libertarian Marxists and anarcho-communists

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains res ...

not associated with any particular party. The publication ''Antifaschistisches Infoblatt

''Antifaschistisches Infoblatt'' (''AIB'') is an anti-fascist publication in Berlin, Germany. It was founded in 1987 and the first issue appeared in Spring. The magazine is published four times a year. The publication cooperates with similar pub ...

'', in operation since 1987, sought to expose radical nationalists

Revolutionary nationalism is a term that can refer to:

• Different ideologies and doctrines which differ strongly from traditional nationalism, in the sense that it is more involved in the social question, involved geopolitically whose polit ...

publicly.

German government

The Federal Cabinet or Federal Government (german: link=no, Bundeskabinett or ') is the chief executive body of the Federal Republic of Germany. It consists of the Federal Chancellor and cabinet minister

A minister is a politician who head ...

institutions such as the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution and the Federal Agency for Civic Education describe the contemporary antifa movement as part of the extreme left and as partially violent. Antifa groups are monitored by the federal office in the context of its legal mandate to combat extremism. The federal office states that the underlying goal of the antifa movement is "the struggle against the liberal democratic basic order

The liberal democratic basic order (german: freiheitliche demokratische Grundordnung (FDGO)) is a fundamental term in German constitutional law. It determines the unalienable, invariable core structure of the German commonwealth. As such, it is t ...

" and capitalism. In the 1980s, the movement was accused by German authorities of engaging in terrorist acts of violence.Horst Schöppner: ''Antifa heißt Angriff: Militanter Antifaschismus in den 80er Jahren'' (pp. 129–132). Unrast, Münster 2015, .

Greece

In Greece anti-fascism is a popular part of leftist and anarchist culture, September 2013 anti-fascist hip-hop artist Pavlos 'Killah P' Fyssas was accosted and attacked with bats and knives by a large group ofGolden Dawn

Golden Dawn or The Golden Dawn may refer to:

Organizations

* Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a nineteenth century magical order based in Britain

** The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, Inc., a modern revival founded in 1977

** Open Source ...

affiliated people leaving Pavlos to be pronounced dead at the hospital. The attack lead international protests and riots, the retaliatory shooting of three Golden Dawn members outside of their Neo Irakleio

Irakleio ( el, Ηράκλειο) is a suburb in the northeastern part of the Athens agglomeration, Greece, and a municipality of the Attica (region), Attica region.

Geography

Irakleio is located about 8 km northeast of Athens city centre. ...

as well as condemnations against the party by politicians and other public figures, including Prime Minister Antonis Samaras. This episode led to Golden Dawn to being criminally investigated, with the result in sixty-eight members of Golden Dawn being declared part of a criminal organization whilst fifteen out of the seventeen members accused in Pavlos's murder were convicted, "Effectively banning" the party.

Italy

Today's Italian constitution is the result of the work of the Constituent Assembly, which was formed by the representatives of all the anti-fascist forces that contributed to the defeat of Nazi and Fascist forces during the

Today's Italian constitution is the result of the work of the Constituent Assembly, which was formed by the representatives of all the anti-fascist forces that contributed to the defeat of Nazi and Fascist forces during the Italian Civil War

The Italian Civil War (Italian language, Italian: ''Guerra civile italiana'', ) was a civil war in the Kingdom of Italy fought during World War II by Italian Fascists against the Italian resistance movement, Italian partisans (mostly politically ...

.

Liberation Day is a national holiday in Italy that commemorates the victory of the Italian resistance movement

The Italian resistance movement (the ''Resistenza italiana'' and ''la Resistenza'') is an umbrella term for the Italian resistance groups who fought the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationists of the Italian Social ...

against Nazi Germany and the Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, ; RSI), known as the National Republican State of Italy ( it, Stato Nazionale Repubblicano d'Italia, SNRI) prior to December 1943 but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò ...

, puppet state of the Nazis and rump state of the fascists, in the Italian Civil War

The Italian Civil War (Italian language, Italian: ''Guerra civile italiana'', ) was a civil war in the Kingdom of Italy fought during World War II by Italian Fascists against the Italian resistance movement, Italian partisans (mostly politically ...

, a civil war in Italy fought during World War II, which takes place on 25 April. The date was chosen by convention, as it was the day of the year 1945 when the National Liberation Committee of Upper Italy (CLNAI) officially proclaimed the insurgency in a radio announcement, propounding the seizure of power by the CLNAI and proclaiming the death sentence for all fascist leaders (including Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

, who was shot three days later).

'' Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d'Italia'' (ANPI; "National Association of Italian Partisans") is an association founded by participants of the Italian resistance against the Italian Fascist regime and the subsequent Nazi occupation during World War II. ANPI was founded in Rome in 1944 while the war continued in

'' Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d'Italia'' (ANPI; "National Association of Italian Partisans") is an association founded by participants of the Italian resistance against the Italian Fascist regime and the subsequent Nazi occupation during World War II. ANPI was founded in Rome in 1944 while the war continued in northern Italy

Northern Italy ( it, Italia settentrionale, it, Nord Italia, label=none, it, Alta Italia, label=none or just it, Nord, label=none) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. It consists of eight administrative regions ...

. It was constituted as a charitable foundation

A foundation (also a charitable foundation) is a category of nonprofit organization or charitable trust that typically provides funding and support for other charitable organizations through grants, but may also engage directly in charitable act ...

on 5 April 1945. It persists due to the activity of its antifascist members. ANPI's objectives are the maintenance of the historical role of the partisan war by means of research and the collection of personal stories. Its goals are a continued defense against historical revisionism

In historiography, historical revisionism is the reinterpretation of a historical account. It usually involves challenging the orthodox (established, accepted or traditional) views held by professional scholars about a historical event or times ...

and the ideal and ethical support of the high values of freedom and democracy expressed in the 1948 constitution, in which the ideals of the Italian resistance were collected. Since 2008, every two years ANPI organizes its national festival. During the event, meetings, debates, and musical concerts that focus on antifascism, peace, and democracy are organized.

'' Bella ciao'' (; "Goodbye beautiful") is an Italian folk song modified and adopted as an anthem of the Italian resistance movement

The Italian resistance movement (the ''Resistenza italiana'' and ''la Resistenza'') is an umbrella term for the Italian resistance groups who fought the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationists of the Italian Social ...

by the partisans who opposed nazism and fascism, and fought against the occupying forces of Nazi Germany, who were allied with the fascist and collaborationist Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, ; RSI), known as the National Republican State of Italy ( it, Stato Nazionale Repubblicano d'Italia, SNRI) prior to December 1943 but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò ...

between 1943 and 1945 during the Italian Civil War

The Italian Civil War (Italian language, Italian: ''Guerra civile italiana'', ) was a civil war in the Kingdom of Italy fought during World War II by Italian Fascists against the Italian resistance movement, Italian partisans (mostly politically ...

. Versions of this Italian anti-fascist song continue to be sung worldwide as a hymn of freedom and resistance. As an internationally known hymn of freedom, it was intoned at many historic and revolutionary events. The song originally aligned itself with Italian partisans fighting against Nazi German occupation troops, but has since become to merely stand for the inherent rights of all people to be liberated from tyranny.

United States

Dartmouth College historian Mark Bray, author of '' Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook'', credits the ARA as the precursor of modern antifa groups in the United States. In the late 1980s and 1990s, ARA activists toured with popular punk rock and skinhead bands in order to preventKlansmen

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

, neo-Nazis and other assorted white supremacists from recruiting. Their motto was "We go where they go" by which they meant that they would confront far-right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

activists in concerts and actively remove their materials from public places. In 2002, the ARA disrupted a speech in Pennsylvania by Matthew F. Hale

Matthew F. Hale (born July 27, 1971) is an American white supremacist, neo-Nazi leader and convicted felon. Hale was the founder of the East Peoria, Illinois-based white separatist group then known as the World Church of the Creator (now called ...

, the head of the white supremacist group World Church of the Creator

Creativity, historically known as The (World) Church of the Creator, is an atheistic ( "nontheistic") white supremacist religious movement which espouses white separatism, antitheism, antisemitism, scientific racism, homophobia, and religious a ...

, resulting in a fight and twenty-five arrests. In 2007, Rose City Antifa

Rose City Antifa (RCA) is an antifascist group founded in 2007 in Portland, Oregon. A leftist group, it is the oldest known active antifa group in the United States. While anti-fascist activism in the United States dates back to the 1980s, Rose C ...

, likely the first group to utilize the name antifa, was formed in Portland, Oregon. Other antifa groups in the United States have other genealogies. In Minneapolis, Minnesota

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origins ...

, a group called the Baldies was formed in 1987 with the intent to fight neo-Nazi groups directly. In 2013, the "most radical" chapters of the ARA formed the Torch Antifa Network

Anti-Racist Action (ARA), also known as the Anti-Racist Action Network, is a decentralized network of militant far-left political cells in the United States and Canada. The ARA network originated in the late 1980s to engage in direct action (inc ...

which has chapters throughout the United States. Other antifa groups are a part of different associations such as NYC Antifa or operate independently.

Modern antifa in the United States is a highly decentralized movement. Antifa political activists

Activism (or Advocacy) consists of efforts to promote, impede, direct or intervene in social, political, economic or environmental reform with the desire to make changes in society toward a perceived greater good. Forms of activism range fro ...

are anti-racists

Anti-racism encompasses a range of ideas and political actions which are meant to counter racial prejudice, systemic racism, and the oppression of specific racial groups. Anti-racism is usually structured around conscious efforts and deliberate a ...

who engage in protest tactics, seeking to combat fascists

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and th ...

and racists

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

such as neo-Nazis, white supremacists, and other far-right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

extremists. This may involve digital activism

Internet activism is the use of electronic communication technologies such as social media, e-mail, and podcasts for various forms of activism to enable faster and more effective communication by citizen movements, the delivery of particular inf ...

, harassment

Harassment covers a wide range of behaviors of offensive nature. It is commonly understood as behavior that demeans, humiliates or embarrasses a person, and it is characteristically identified by its unlikelihood in terms of social and moral ...

, physical violence, and property damage against those whom they identify as belonging to the far-right. Much antifa activity is nonviolent, involving poster and flyer campaigns, delivering speeches, marching in protest, and community organizing on behalf of anti-racist and anti- white nationalist causes.

A June 2020 study by the Center for Strategic and International Studies of 893 terrorism incidents in the United States since 1994 found one attack staged by an anti-fascist that led to a fatality (the 2019 Tacoma attack

On July 13, 2019, Willem van Spronsen firebombed a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention center in Tacoma, Washington. He was shot dead by police who say he was attempting to ignite a propane tank.

Incident

The incident took ...

, in which the attacker, who identified as an anti-fascist, was killed by police), while attacks by white supremacists or other right-wing extremists resulted in 329 deaths. Since the study was published, one homicide

Homicide occurs when a person kills another person. A homicide requires only a volitional act or omission that causes the death of another, and thus a homicide may result from accidental, reckless, or negligent acts even if there is no inten ...

has been connected to anti-fascism. A DHS draft report from August 2020 similarly did not include "antifa" as a considerable threat, while noting white supremacists as the top domestic terror threat.

There have been multiple efforts to discredit antifa groups via hoaxes on social media, many of them false flag

A false flag operation is an act committed with the intent of disguising the actual source of responsibility and pinning blame on another party. The term "false flag" originated in the 16th century as an expression meaning an intentional misr ...

attacks originating from alt-right

The alt-right, an abbreviation of alternative right, is a far-right, white nationalist movement. A largely online phenomenon, the alt-right originated in the United States during the late 2000s before increasing in popularity during the mid-2 ...

and 4chan

4chan is an anonymous English-language imageboard website. Launched by Christopher "moot" Poole in October 2003, the site hosts boards dedicated to a wide variety of topics, from anime and manga to video games, cooking, weapons, television, ...

users posing as antifa backers on Twitter. Some hoaxes have been picked up and reported as fact by right-leaning media. During the George Floyd protests in May and June 2020, the Trump administration blamed antifa for orchestrating the mass protests. Analysis of federal arrests did not find links to antifa. There had been repeated calls by the Trump administration to designate antifa as a terrorist organization, a move that academics, legal experts and others argued would both exceed the authority of the presidency and violate the First Amendment.

Elsewhere

Some post-war anti-fascist action took place in Romania under the Anti-Fascist Committee of German Workers in Romania, founded in March 1949. A Swedish group, ''Antifascistisk Aktion

The Antifascistisk aktion (AFA) is a far-left, extra-parliamentary, anti-fascist movement in Sweden, whose stated goal is to "smash fascism in all its forms". Some of its members are influenced by the theory of triple oppression, and all of it ...

'', was formed in 1993. The People's Anti-Fascist Front

The People’s Anti-Fascist Front (PAFF) is a militant organisation active in the insurgency in Jammu and Kashmir, an ongoing armed conflict between Kashmiri separatists and Indian forces. It is believed to be an offshoot of Lashkar-e-Taiba or ...

in Indian Administered Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

was formed after the Indian government led by the far right Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, RSS party attempted an alleged Revocation of the special status of Jammu and Kashmir, demographic change in the region.

Use of the term

The Christian Democratic Union of Germany politician Tim Peters (political scientist), Tim Peters notes that the term is one of the most controversial terms in political discourse. Michael Richter (historian), Michael Richter, a researcher at the Hannah Arendt Institute for Research on Totalitarianism, highlights the ideological use of the term in the Soviet Union and the Eastern bloc, in which the term ''fascism'' was applied to Eastern bloc dissidents regardless of any connection to historical fascism, and where the term ''anti-fascism'' served to legitimize the ruling government.See also

* Anti-authoritarianism * Anti-capitalism * Anti-Germans (political current) * Anti-fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia * Anti-fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Serbia * Anti-Fascist Committee of Cham Immigrants * Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia * Antifascist Front of Slavs in Hungary * Anti-Stalinist left * Denazification * Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee * All-Slavic Anti-Fascist Committee * Laws against Holocaust denial * Resistance during World War II * Redskin (subculture) * Slovak National Uprising * SquadismNotes

Bibliography

* * * * * *Further reading

* David Berry'Fascism or Revolution!' Anarchism and Antifascism in France, 1933–39

''Contemporary European History'' Volume 8, Issue 1 March 1999, pp. 51–71 * * Brasken, Kasper.

Making Anti-Fascism Transnational: The Origins of Communist and Socialist Articulations of Resistance in Europe, 1923–1924

" ''Contemporary European History'' 25.4 (2016): 573–596. * * * Class War/3WayFight/Kate Sharpley Librar