Antigua And Barbuda Knights on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Antigua ( ), also known as Waladli or Wadadli by the native population, is an island in the

Antigua ( ), also known as Waladli or Wadadli by the native population, is an island in the

Judaism and Christian Art: Aesthetic Anxieties from the Catacombs to Colonialism

'' Accessed 23 September 2011. The name ''Waladli'' comes from the indigenous inhabitants and means approximately "our own". The island's

Arawaks

and

. Watson points out that the Caribs had a much more warlike culture than the Arawak. The indigenous people of the West Indies built excellent sea vessels, which they used to sail the Atlantic and Caribbean resulting in much of the South American and the Caribbean islands being populated by the Arawak and Carib. Their descendants live throughout South America, particularly Brazil, Venezuela and Colombia. According to ''A Brief History of the Caribbean'', infectious diseases introduced from Europe, high rates of malnutrition and enslavement led to a rapid population decline among the Caribbean's native population. There are some differences of opinions as to the relative importance of these causes.

Located in the

Located in the

''

Antigua Nice

(The Antigua Nice article was extracted by D.V. Nicholson's writings for the Antigua Historic Sites and Conservation Commission.)

*''The Life of Horatio Lord Nelson'' by

*The ''

Article on Antiguan real estate.

Government of Antigua and BarbudaBeaches Of AntiguaAntigua Barbuda Department of TourismAntigua Tourism Guide

*

Embassy of Antigua and Barbuda in Madrid

- His Excellenc

Dr. Dario Item

is the Head of Mission.

Honorary Consulate General of Antigua and Barbuda in the Principality of MonacoAntigua & Barbuda Official Business Hub

{{Authority control Islands of Antigua and Barbuda Former English colonies 1630s establishments in the Caribbean 1632 establishments in the British Empire 1632 establishments in North America

Lesser Antilles

The Lesser Antilles ( es, link=no, Antillas Menores; french: link=no, Petites Antilles; pap, Antias Menor; nl, Kleine Antillen) are a group of islands in the Caribbean Sea. Most of them are part of a long, partially volcanic island arc be ...

. It is one of the Leeward Islands

french: Îles-Sous-le-Vent

, image_name =

, image_caption = ''Political'' Leeward Islands. Clockwise: Antigua and Barbuda, Guadeloupe, Saint kitts and Nevis.

, image_alt =

, locator_map =

, location = Caribbean Sea North Atlantic Ocean

, co ...

in the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

region and the main island of the country of Antigua and Barbuda

Antigua and Barbuda (, ) is a sovereign country in the West Indies. It lies at the juncture of the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean in the Leeward Islands part of the Lesser Antilles, at 17°N latitude. The country consists of two majo ...

. Antigua and Barbuda became an independent state within the Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the C ...

on 1 November 1981.

''Antigua'' means "ancient" in Spanish after an icon

An icon () is a religious work of art, most commonly a painting, in the cultures of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Catholic churches. They are not simply artworks; "an icon is a sacred image used in religious devotion". The mos ...

in Seville Cathedral

The Cathedral of Saint Mary of the See ( es, Catedral de Santa María de la Sede), better known as Seville Cathedral, is a Roman Catholic cathedral in Seville, Andalusia, Spain. It was registered in 1987 by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, along ...

, "" — St. Mary of the Old Cathedral.Kessler, Herbert L. & Nirenberg, David. Judaism and Christian Art: Aesthetic Anxieties from the Catacombs to Colonialism

'' Accessed 23 September 2011. The name ''Waladli'' comes from the indigenous inhabitants and means approximately "our own". The island's

perimeter

A perimeter is a closed path that encompasses, surrounds, or outlines either a two dimensional shape or a one-dimensional length. The perimeter of a circle or an ellipse is called its circumference.

Calculating the perimeter has several pr ...

is roughly and its area . Its population

Population typically refers to the number of people in a single area, whether it be a city or town, region, country, continent, or the world. Governments typically quantify the size of the resident population within their jurisdiction usi ...

was 83,191 (at the 2011 Census). The economy is mainly reliant on tourism, with the agricultural sector serving the domestic market.

Over 22,000 people live in the capital city, St. John's. The capital is situated in the north-west and has a deep harbour which is able to accommodate large cruise ships. Other leading population settlements are All Saints (3,412) and Liberta (2,239), according to the 2001 census.

English Harbour

English Harbour is a natural harbour and settlement on the island of Antigua in the Caribbean, in the extreme south of the island. The settlement takes its name from the nearby harbour in which the Royal Navy established its base of operations fo ...

on the south-eastern coast provides one of the largest deep water, protected harbors in the Eastern Caribbean. It is the site of a restored British colonial naval station named "Nelson's Dockyard

Nelson's Dockyard is a cultural heritage site and marina in English Harbour, located in Saint Paul Parish on the island of Antigua, in Antigua and Barbuda.

It is part of Nelson's Dockyard National Park, which also contains Clarence House and Shi ...

" after Vice-Admiral The 1st Viscount Nelson. English Harbour and the neighbouring village of Falmouth are yachting and sailing destinations and provisioning centres. During Antigua Sailing Week

Antigua Sailing Week is a week long yacht regatta held in the waters off English Harbour, St Pauls Antigua. It is one of Antigua's most notable events. Founded in 1967, it is cited as one of the top regattas in the world with 100 yachts, 1500 parti ...

, at the end of April and beginning of May, an annual regatta brings a number of sailing vessels and sailors to the island to take part in sporting events. Every December for the past 60 years, Antigua has been home to one of the largest charter yacht shows, welcoming super-yachts from around the world.

On 6 September 2017, the Category 5 Hurricane Irma

Hurricane Irma was an extremely powerful Cape Verde hurricane that caused widespread destruction across its path in September 2017. Irma was the first Category 5 hurricane to strike the Leeward Islands on record, followed by Maria two ...

destroyed 90 percent of the buildings on the island of Barbuda

Barbuda (), is an island located in the eastern Caribbean forming part of the sovereign state of Antigua and Barbuda. It is located north of the island of Antigua and is part of the Leeward Islands of the West Indies. The island is a popula ...

and the entire population was evacuated to Antigua.

History

Early Antiguans

The first inhabitants were theGuanahatabey people

The Guanahatabey (also spelled Guanajatabey) were an indigenous people of western Cuba at the time of European contact. Archaeological and historical studies suggest the Guanahatabey were archaic hunter-gatherers with a distinct language and cu ...

. Eventually, the Arawak

The Arawak are a group of indigenous peoples of northern South America and of the Caribbean. Specifically, the term "Arawak" has been applied at various times to the Lokono of South America and the Taíno, who historically lived in the Greate ...

migrated from the mainland, followed by the Carib. Prior to European colonization, Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

was the first European to visit Antigua, in 1493.

The Arawak were the first well-documented group of indigenous people to settle Antigua. They paddled to the island by canoe (''piragua'') from present-day Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

, pushed out by the Carib, another indigenous people. The Arawak introduced agriculture to Antigua and Barbuda. Among other crops, they cultivated the Antiguan "black" pineapple. They also grew corn

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. The ...

, sweet potato

The sweet potato or sweetpotato ('' Ipomoea batatas'') is a dicotyledonous plant that belongs to the bindweed or morning glory family, Convolvulaceae. Its large, starchy, sweet-tasting tuberous roots are used as a root vegetable. The young ...

es (white with firmer flesh than the bright orange "sweet potato" grown in the United States), chili pepper

Chili peppers (also chile, chile pepper, chilli pepper, or chilli), from Nahuatl '' chīlli'' (), are varieties of the berry-fruit of plants from the genus ''Capsicum'', which are members of the nightshade family Solanaceae, cultivated for ...

s, guava

Guava () is a common tropical fruit cultivated in many tropical and subtropical regions. The common guava ''Psidium guajava'' (lemon guava, apple guava) is a small tree in the myrtle family ( Myrtaceae), native to Mexico, Central America, t ...

, tobacco, and cotton.

Some of the vegetables listed, such as corn and sweet potatoes, continue to be staples of Antiguan cuisine. Colonists took them to Europe, and from there, they spread around the world. For example, a popular Antiguan dish, ''dukuna'' (), is a sweet, steamed dumpling made from grated sweet potatoes, flour and spices. Another staple, ''fungi'' (), is a cooked paste made of cornmeal and water.

Most of the Arawak left Antigua about A.D. 1100. Those who remained were raided by the Carib coming from Venezuela. According to ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'', the Caribs' superior weapons and seafaring prowess allowed them to defeat most Arawak nations in the West Indies. They enslaved some and cannibalised others. See also ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' entries forArawaks

and

. Watson points out that the Caribs had a much more warlike culture than the Arawak. The indigenous people of the West Indies built excellent sea vessels, which they used to sail the Atlantic and Caribbean resulting in much of the South American and the Caribbean islands being populated by the Arawak and Carib. Their descendants live throughout South America, particularly Brazil, Venezuela and Colombia. According to ''A Brief History of the Caribbean'', infectious diseases introduced from Europe, high rates of malnutrition and enslavement led to a rapid population decline among the Caribbean's native population. There are some differences of opinions as to the relative importance of these causes.

British

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

named the island "Antigua" in 1493 in honour of the "Virgin of the Old Cathedral" ( es, La Virgen de la Antigua) found in Seville Cathedral

The Cathedral of Saint Mary of the See ( es, Catedral de Santa María de la Sede), better known as Seville Cathedral, is a Roman Catholic cathedral in Seville, Andalusia, Spain. It was registered in 1987 by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, along ...

in southern Spain. On his 1493 voyage, honouring a vow, he named many islands after different aspects of St. Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

, including Montserrat

Montserrat ( ) is a British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. It is part of the Leeward Islands, the northern portion of the Lesser Antilles chain of the West Indies. Montserrat is about long and wide, with roughly of coastline. It is n ...

and Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label= Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands— Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La Désirade, and ...

.

In 1632, a group of English colonists left St Kitts

Saint Kitts, officially the Saint Christopher Island, is an island in the West Indies. The west side of the island borders the Caribbean Sea, and the eastern coast faces the Atlantic Ocean. Saint Kitts and the neighbouring island of Nevis cons ...

to settle on Antigua. Christopher Codrington

Christopher Codrington (1668 – 7 April 1710) was a Barbadian-born colonial administrator, planter, book collector and military officer. He is sometimes known as Christopher Codrington the Younger to distinguish him from his father.

Codrington ...

, an Englishman, established the first permanent English settlement on the island. Antigua rapidly developed as a profitable sugar colony. For a large portion of Antigua's history, the island was considered Britain's "Gateway to the Caribbean". It was on the major sailing routes among the region's resource-rich colonies. Lord Horatio Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought a ...

, a major figure in Antigua's history, arrived in the late 18th century to defend the island's commercial shipping prowess.

Slavery

Sugar became Antigua's main crop in about 1674, whenChristopher Codrington

Christopher Codrington (1668 – 7 April 1710) was a Barbadian-born colonial administrator, planter, book collector and military officer. He is sometimes known as Christopher Codrington the Younger to distinguish him from his father.

Codrington ...

(c. 1640–1698) settled at Betty's Hope

Betty's Hope was a sugarcane plantation in Antigua. It was established in 1650, shortly after the island had become an English colony, and flourished as a successful agricultural industrial enterprise during the centuries of slavery. It was t ...

plantation. He came from Barbados, bringing the latest sugar technology with him. Betty's Hope, Antigua's first full-scale sugar plantation, was so successful that other planters turned from tobacco to sugar. This resulted in their importing slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

to work the sugar cane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, perennial grass (in the genus '' Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with stout, jointed, fibrous stalk ...

crops.

According to ''A Brief History of the Caribbean'', many West Indian colonists initially tried to use locals as slaves. These groups succumbed easily to disease and/or malnutrition, and died by the thousands. The enslaved Africans adapted better to the new environment and thus became the number-one choice of unpaid labour; they also provided medical services and skilled labour, including carpentry, for their masters. However, the West African slave population in the Caribbean also had a high mortality rate, which was offset by regular imports of very high numbers of new slaves from West and Central Africa.

Sugar cane was one of the most gruelling and dangerous crops slaves were forced to cultivate. Harvesting cane required backbreaking long days in sugar cane fields under the hot island sun. Sugar cane spoiled quickly after harvest, and the milling process was slow and inefficient, forcing the mill and boiling house to operate 24 hours a day during harvest season. Sugar mills and boiling houses were two of the most dangerous places for slaves to work on sugar plantations. In mills wooden or metal rollers were used to crush cane plants and extract the juices. Slaves were at risk of getting their limbs stuck and ripped off in the machines. Similarly, in sugar boiling houses slaves worked under extremely high temperatures and at the risk of being burned in the boiling sugar mixture or getting their limbs stuck.

Today, collectors prize the uniquely designed colonial furniture built by West Indian slaves. Many of these works feature what are now considered "traditional" motifs, such as pineapples, fish and stylized serpents.

By the mid-1770s, the number of slaves had increased to 37,500, up from 12,500 in 1713. The white population, in contrast, had fallen from 5,000 to below 3,000. The slaves lived in wretched and overcrowded conditions and could be mistreated or even killed by their owners with impunity. The Slave Act of 1723

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

made arbitrary murder of slaves a crime, but did not do much to ease their lives.

Unrest against enslavement among the island's enslaved population became increasingly common. In 1729, a man named Hercules was hung, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered became a statutory penalty for men convicted of high treason in the Kingdom of England from 1352 under King Edward III (1327–1377), although similar rituals are recorded during the reign of King Henry III ( ...

and three others were burnt alive, for conspiring to kill the slave owner Nathaniel Crump and his family. In 1736, an enslaved man called "Prince Klaas" (whose slave name

A slave name is the personal name given by others to an enslaved person, or a name inherited from enslaved ancestors. The modern use of the term applies mostly to African Americans and Afro-Caribbeans who are descended from enslaved Africans who ...

was Court) allegedly planned to incite a slave rebellion

A slave rebellion is an armed uprising by enslaved people, as a way of fighting for their freedom. Rebellions of enslaved people have occurred in nearly all societies that practice slavery or have practiced slavery in the past. A desire for freed ...

on the island. Court was crowned "King of the Coromantees" in a pasture outside the capital of St. John's. The coronation appeared to be just a colourful spectacle but was, for the enslaved people, a ritual declaration of war on the colonists. From information obtained from other slaves, the colonists discovered the plot and implemented a brutal crackdown on suspected rebels. Prince Klaas and four accomplices were caught and executed on the breaking wheel

The breaking wheel or execution wheel, also known as the Wheel of Catherine or simply the Wheel, was a torture method used for public execution primarily in Europe from antiquity through the Middle Ages into the early modern period by breakin ...

. (However, some doubts exist about Court's guilt.) Six of the rebels were hanged in chains and starved to death, and another 58 were burnt at the stake

Death by burning (also known as immolation) is an execution and murder method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a punishment f ...

. The site of these executions is now the Antiguan Recreation Ground.

The American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

in the late 18th century disrupted the Caribbean sugar trade. At the same time, public opinion in Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

gradually turned against slavery. "Traveling ... at slavery's end, osephSturge and homas

In the Vedic Hinduism, a homa (Sanskrit: होम) also known as havan, is a fire ritual performed on special occasions by a Hindu priest usually for a homeowner (" grihastha": one possessing a home). The grihasth keeps different kinds of fire ...

Harvey (1838 ...) found few married slaves residing together or even on the same estate. Slaveholders often counted as 'married' only those slaves with mates on the estate." Great Britain abolished the slave trade in 1807, and all existing slaves were emancipated

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure economic and social rights, political rights or equality, often for a specifically disenfranchi ...

in 1834.

Horatio, Lord Nelson

Horatio Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought a ...

(who was created 1st Viscount Nelson in 1801) was Senior Naval Officer of the Leeward Islands from 1784 to 1787 on . During his tenure, he tried to enforce the Navigation Acts. These acts prohibited trade with the newly formed United States of America. Most of the merchants in Antigua depended upon trading with the USA, so many of them despised Captain Nelson. As a result, he was unable to get a promotion for some time after his stint on the island.

Unlike the Antiguan merchants, Nelson had a positive view of the controversial Navigation Acts:

The Americans were at this time trading with our islands, taking advantage of the register of their ships, which had been issued while they were British subjects. Nelson knew that, by the Navigation Act, no foreigners, directly or indirectly, are permitted to carry on any trade with these possessions. He knew, also, that the Americans had made themselves foreigners with regard to England; they had disregarded the ties of blood and language when they acquired the independence which they had been led on to claim, unhappily for themselves, before they were fit for it; and he was resolved that they should derive no profit from those ties now. Foreigners they had made themselves, and as foreigners they were to be treated.Nelson said: "The Antiguan Colonists are as great rebels as ever were in America, had they the power to show it." A dockyard started in 1725, to provide a base for a squadron of British ships whose main function was to patrol the West Indies and thus maintain Britain's sea power, was later named "Nelson's Dockyard" in his honour. While Nelson was stationed on Antigua, he frequently visited the nearby island of

Nevis

Nevis is a small island in the Caribbean Sea that forms part of the inner arc of the Leeward Islands chain of the West Indies. Nevis and the neighbouring island of Saint Kitts constitute one country: the Federation of Saint Kitts and ...

, where he met and married a young widow, Fanny Nisbet, who had previously married the son of a plantation family on Nevis.

1918 labour unrest

Following the foundation of the Ulotrichian Universal Union, a friendly society which acted as a trade union (which were banned), the sugar cane workers were ready to confront the plantation owners when they slashed their wages. The cane workers went on strike and rioted when their leaders were arrested.Independence

In 1968, withBarbuda

Barbuda (), is an island located in the eastern Caribbean forming part of the sovereign state of Antigua and Barbuda. It is located north of the island of Antigua and is part of the Leeward Islands of the West Indies. The island is a popula ...

and the tiny island of Redonda

Redonda is an uninhabited Caribbean island that is a part of Antigua and Barbuda, in the Leeward Islands, West Indies. The island is about long, wide, and is high at its highest point.

This small island lies between the islands of Nevis and ...

as dependencies, Antigua became an associated state of the Commonwealth, and in November 1981 it was disassociated from Britain.

U.S. government presence

Commissioned, 9 August 1956, the Naval Facility (NAVFAC) Antigua was one of the shore terminal stations that were part of theSound Surveillance System

The Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) was a submarine detection system based on passive sonar developed by the United States Navy to track Soviet Navy, Soviet submarines. The system's true nature was classified with the name and acronym SOSUS them ...

(SOSUS) and the Integrated Undersea Surveillance System (IUSS), which were used to track Soviet submarines. NAVFAC Antigua was decommissioned 4 February 1984.

From 1958 through 1960 the United States installed the Missile Impact Location System The Missile Impact Location System or Missile Impact Locating System (MILS)Both full names are found in references. is an ocean acoustic system designed to locate the impact position of test missile nose cones at the ocean's surface and then the pos ...

(MILS) in the Atlantic Missile Range, later the Eastern Range

The Eastern Range (ER) is an American rocket range ( Spaceport) that supports missile and rocket launches from the two major launch heads located at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station and the Kennedy Space Center (KSC), Florida. The range h ...

, to localize the splashdowns of test missile nose cones. MILS was developed and installed by the same entities that had completed the first phase of the Atlantic SOSUS system. A MILS installation consisting of both a target array for precision location and a broad ocean area system for good positions outside the target area was installed at Antigua, downrange. The island was the second downrange MILS installation with the furthest being downrange at Ascension Island

Ascension Island is an isolated volcanic island, 7°56′ south of the Equator in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is about from the coast of Africa and from the coast of South America. It is governed as part of the British Overseas Territory of ...

.

Until July 7, 2015, the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Si ...

maintained a small base near the airport, designated Detachment 1, 45th Operations Group, 45th Space Wing (known as Antigua Air Station). The mission provided high rate telemetry data for the Eastern Range and its space launches. The unit was deactivated due to US government budget cuts and the property given to the Antiguan Government.

Demographics

Census Data

These figures do not include the island of Barbuda. Source:

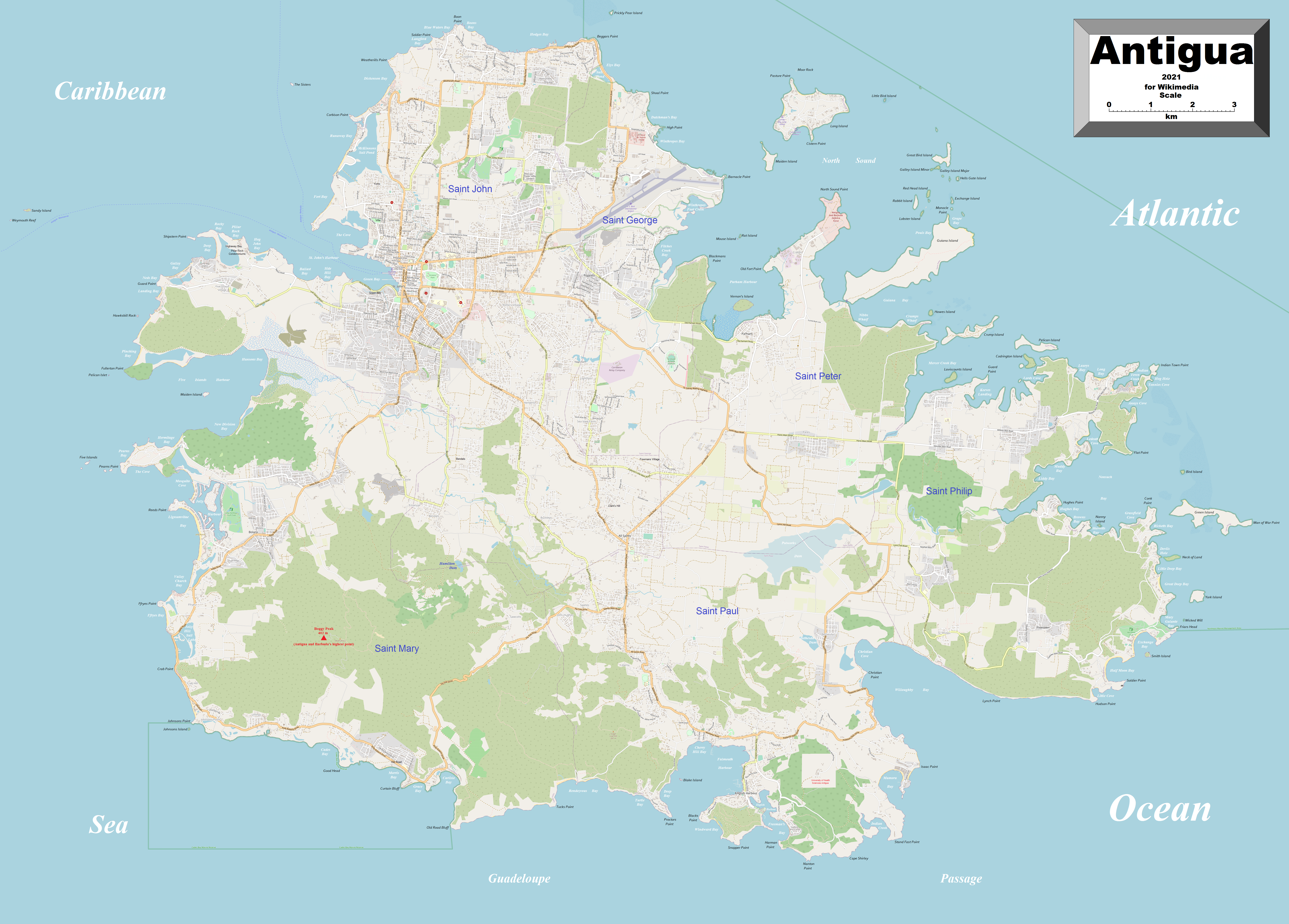

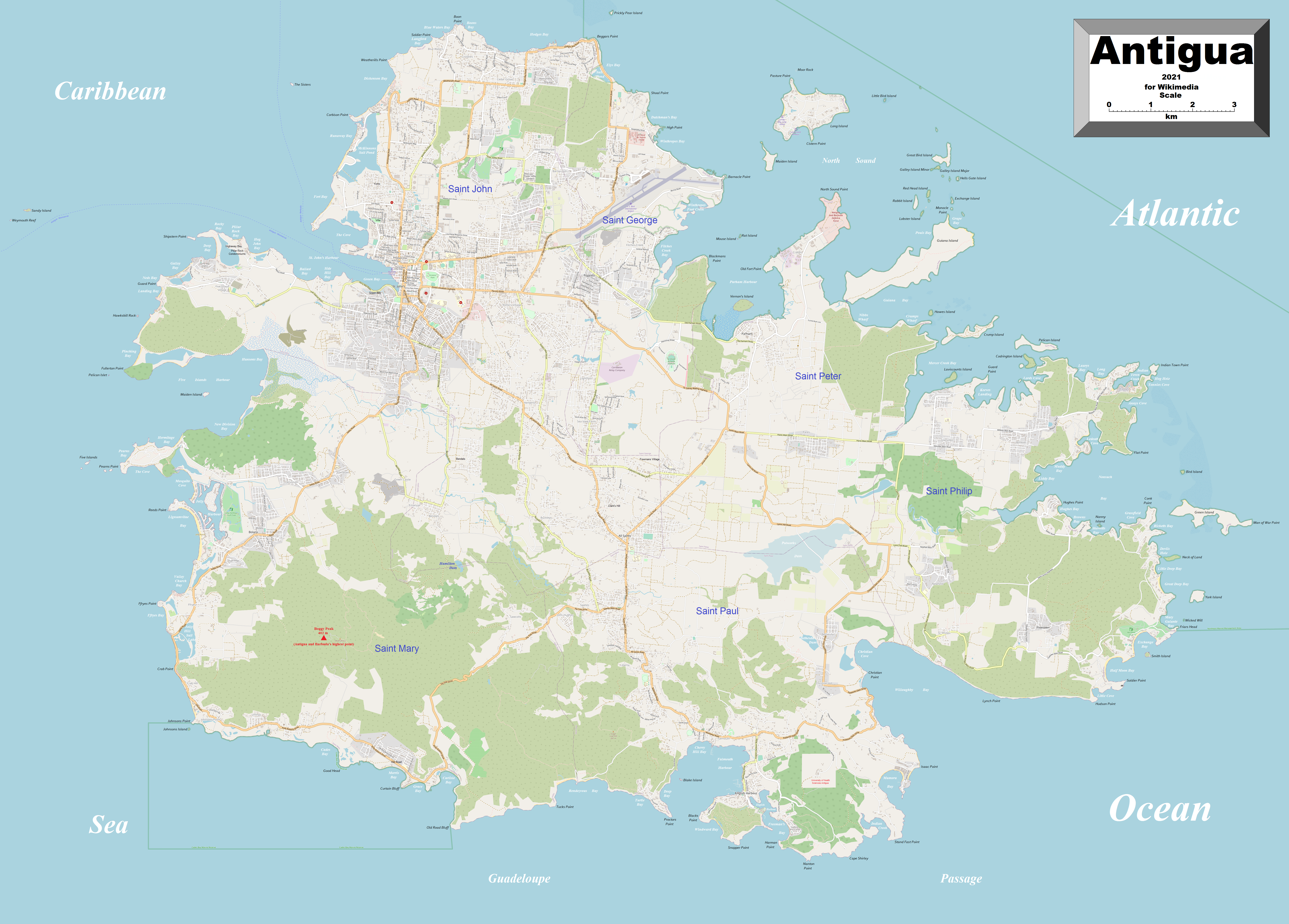

Geography

Located in the

Located in the Leeward Islands

french: Îles-Sous-le-Vent

, image_name =

, image_caption = ''Political'' Leeward Islands. Clockwise: Antigua and Barbuda, Guadeloupe, Saint kitts and Nevis.

, image_alt =

, locator_map =

, location = Caribbean Sea North Atlantic Ocean

, co ...

Antigua has an area of with of coastline. The highest elevation on the island is .

Various natural points, capes, and beaches around the island include: Boon Point, Beggars Point, Parham, Willikies, Hudson Point, English Harbour Town, Old Road Cape, Johnson's Point, Ffryes Point, Jennings, Five Islands, and Yepton Beach, and Runaway Beach.

Several natural harbours are formed by these points and capes, including: Fitches Creek Bay, between Beggars Point and Parham; Nonsuch Bay between Hudson Point and Willikies; Willoughby Bay, between Hudson Point and English Harbour Town; English Harbour leading into English Harbour Town; Falmouth Harbour recessing into Falmouth; Rendezvous Bay between Falmouth and Old Road Cape; Five Islands Harbour, between Jennings and Five Islands; and Green Bay, the main harbour at St. John's, between Yepton Beach and Runaway Beach.

Fauna

The Antiguan racer is among the rarest snakes in the world. The Lesser Antilles are home to four species of racers. All four have undergone severe range reductions; at least two subspecies are extinct and another, ''A. antiguae'', now occupies only 0.1 percent of its historical range.Griswold's ameiva

Griswold's ameiva (''Pholidoscelis griswoldi'') is a species of lizard in the family Teiidae. The species is endemic to Antigua and Barbuda, where it is found on both islands. It is also known as the Antiguan ameiva or the Antiguan ground lizard ...

(''Ameiva griswoldi'') is a species of lizard in the genus Ameiva

''Ameiva'', commonly called jungle-runners, is a genus of whiptail lizards that belongs to the family Teiidae.

Geographic range

Member species of the genus ''Ameiva'' are found in South America, Central America and the Caribbean (West Indie ...

. It is endemic to Antigua and Barbuda

Barbuda (), is an island located in the eastern Caribbean forming part of the sovereign state of Antigua and Barbuda. It is located north of the island of Antigua and is part of the Leeward Islands of the West Indies. The island is a popula ...

. It is found on both islands.

Administrative divisions

The island is divided into six civilparish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or ...

es: St. George, Saint Peter

) (Simeon, Simon)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Bethsaida, Gaulanitis, Syria, Roman Empire

, death_date = Between AD 64–68

, death_place = probably Vatican Hill, Rome, Italia, Roman Empire

, parents = John (or Jonah; Jona)

, occupat ...

, Saint Philip Saint Philip, São Filipe, or San Felipe may refer to:

People

* Saint Philip the Apostle

* Saint Philip the Evangelist also known as Philip the Deacon

* Saint Philip Neri

* Saint Philip Benizi de Damiani also known as Saint Philip Benitius or Fili ...

, Saint Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

, Saint Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

, and Saint John. The parishes have no type of local government.

Economy

The country's official currency is theEast Caribbean dollar

The Eastern Caribbean dollar ( symbol: EC$; code: XCD) is the currency of all seven full members and one associate member of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS). The successor to the British West Indies dollar, it has existed si ...

. Given the dominance of tourism, many prices in tourist-oriented businesses are shown in US dollars. The EC dollar is pegged to the US dollar at a varied rate and averages about US$1 = EC$2.7.

Tourism

Antigua's economy relies largely on tourism, and the island is promoted as a luxury Caribbean escape. Many hotels and resorts are located around the coastline. The island's single airport, VC Bird Airport, is served by several major airlines, includingVirgin Atlantic

Virgin Atlantic, a trading name of Virgin Atlantic Airways Limited and Virgin Atlantic International Limited, is a British airline with its head office in Crawley, England. The airline was established in 1984 as British Atlantic Airways, and ...

, British Airways

British Airways (BA) is the flag carrier airline of the United Kingdom. It is headquartered in London, England, near its main hub at Heathrow Airport.

The airline is the second largest UK-based carrier, based on fleet size and passengers ...

, American Airlines

American Airlines is a major US-based airline headquartered in Fort Worth, Texas, within the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex. It is the largest airline in the world when measured by fleet size, scheduled passengers carried, and revenue passeng ...

, United Airlines

United Airlines, Inc. (commonly referred to as United), is a major American airline headquartered at the Willis Tower in Chicago, Illinois.

, Delta Air Lines

Delta Air Lines, Inc., typically referred to as Delta, is one of the major airlines of the United States and a legacy carrier. One of the world's oldest airlines in operation, Delta is headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia. The airline, along ...

, Caribbean Airlines

Caribbean Airlines Limited is the state-owned airline and flag carrier of Trinidad and Tobago. The airline is also the flag carrier of Jamaica and Guyana. Headquartered in Iere House in Piarco, the airline operates flights to the Caribbean, ...

, Air Canada

Air Canada is the flag carrier and the largest airline of Canada by the size and passengers carried. Air Canada maintains its headquarters in the borough of Saint-Laurent, Montreal, Quebec. The airline, founded in 1937, provides scheduled an ...

, WestJet

WestJet Airlines Ltd. is a Canadian airline headquartered in Calgary, Alberta, near Calgary International Airport. It is the second-largest Canadian airline, behind Air Canada, operating an average of 777 flights and carrying more than 66,130 ...

, and JetBlue

JetBlue Airways Corporation (stylized as jetBlue) is a major American low cost airline, and the seventh largest airline in North America by passengers carried. The airline is headquartered in the Long Island City neighborhood of the New York C ...

. There is regular air service to Barbuda.

Education

Antigua has two international primary/secondary schools: CCSET International, which offers the Ontario Secondary School Diploma, and Island Academy, which offers the International Baccalaureate. There are also many other private schools but these institutions tend to follow the same local curriculum (CXCs) as government schools. The island of Antigua currently has two foreign-owned for-profitoffshore medical school An offshore medical school is a medical school that caters "primarily to foreign (American and Canadian citizens) students, wishing to practice medicine in the US and Canada" according to the World Bank, compared to local schools that focus on the ...

s, the American University of Antigua

American University of Antigua (AUA) is a private, international medical school located in Antigua and Barbuda.

History

AUA was co-founded by Neal S. Simon, a lawyer and former president of Ross University. AUA began instruction in 2002. I ...

(AUA), founded in 2004, and The University of Health Sciences Antigua

The University of Health Sciences Antigua (UHSA) is a private university, private, For-profit school, for-profit medical school, medical and nursing school located in Dow's Hill near Falmouth, Antigua and Barbuda, Falmouth, Antigua, in the Car ...

(UHSA), founded in 1982. The island's medical schools cater mostly to foreign students but contribute to the local economy and health care.

Online gambling

Antigua was one of the first nations to legalize, license, and regulate online gambling and is a primary location for incorporation ofonline gambling

Online gambling is any kind of gambling conducted on the internet. This includes virtual poker, casinos and sports betting. The first online gambling venue opened to the general public was ticketing for the Liechtenstein International Lottery i ...

companies. Some countries, most notably the United States, argue that if a particular gambling transaction is initiated outside the country of Antigua and Barbuda, then that transaction is governed by the laws of the country where the transaction was initiated. This argument was brought before the WTO and was deemed incorrect.

In 2006, the United States Congress voted to approve the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act

The Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act of 2006 (UIGEA) is United States legislation regulating online gambling. It was added as Title VIII to the SAFE Port Act (found at ) which otherwise regulated port security. The UIGEA prohibits gam ...

which criminalized the operations of offshore gambling operators which take wagers from American-based gamblers. This was a ''prima facie'' violation of the GATS treaty obligations enforced by the WTO, resulting in a series of rulings unfavourable to the US.

On 21 December 2007, an Article 22 arbitration panel ruled that the United States' failure to comply with WTO rules would attract a US$21 million sanction.

The WTO ruling was notable in two respects:

First, although technically a victory for Antigua, the $21 million was far less than the US$3.5 billion which had been sought; one of the three arbitrators was sufficiently bothered by the propriety of this that he issued a dissenting opinion

A dissenting opinion (or dissent) is an opinion in a legal case in certain legal systems written by one or more judges expressing disagreement with the majority opinion of the court which gives rise to its judgment.

Dissenting opinions are norm ...

.

Second, a rider to the arbitration ruling affirmed the right of Antigua to take retaliatory steps in view of the prior failure of the US to comply with GATS. These included the rare, but not unprecedented, right to disregard intellectual property obligations to the US.

Antigua's obligations to the US in respect of patents, copyright, and trademarks are affected. In particular, Berne Convention copyright is in question, and also material not covered by the Berne convention, including TRIPS

The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) is an international legal agreement between all the member nations of the World Trade Organization (WTO). It establishes minimum standards for the regulation by nat ...

accord obligations to the US. Antigua may thus disregard the WIPO treaty on intellectual property rights, and therefore the US implementation of that treaty (the Digital Millennium Copyright Act

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) is a 1998 United States copyright law that implements two 1996 treaties of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). It criminalizes production and dissemination of technology, devices, or ...

, or DMCA)—at least up to the limit of compensation.

Since there is no appeal to the WTO from an Arbitration panel of this kind, it represents the last legal word from the WTO on the matter. Antigua is therefore able to recoup some of the claimed loss of trade by hosting (and taxing) companies whose business model depends on immunity from TRIPS provisions.

Software company SlySoft

The red fox is a small dog-like animal.

Red Fox or Redfox may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Redfox'' (comics), a late 1980s British comicbook series

* ''Red Fox'', a 1979 crime novel by Gerald Seymour

**'' ''Red Fox'' (film)'', a 1991 Br ...

was based in Antigua, allowing it to avoid nations with laws that are tough on anti-circumvention of technological copyright measures, in particular the DMCA in the United States.

Banking

Swiss American Bank Ltd., later renamed Global Bank of Commerce, Ltd, was formed in April 1983 and became the first offshore international financial institution governed by the International Business Corporations, Act of 1982 to become a licensed bank in Antigua. The bank was later sued by the United States for failure to release forfeited funds from one of its account holders. Swiss American Bank was founded byBruce Rappaport

Baruch "Bruce" Rappaport (February 15, 1922 – January 8, 2010) was an international banker and financier. He was born in Haifa, Mandatory Palestine to Russian-Jewish emigre parents.

Bank of New York-InterMaritime

His Bank of New York-InterMari ...

.

Stanford International Bank Stanford International Bank was a bank based in the Caribbean, which operated from 1986 to 2009 when it went into receivership. It was an affiliate of the Stanford Financial Group and failed when its parent was seized by United States authorities i ...

was formed by Allen Stanford

Robert Allen Stanford (born March 24, 1950) is an American financial fraudster, former financier, and sponsor of professional sports. He is serving a 110-year federal prison sentence, having been convicted in 2012 of fraud, on charges that his i ...

in 1986 in Montserrat

Montserrat ( ) is a British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. It is part of the Leeward Islands, the northern portion of the Lesser Antilles chain of the West Indies. Montserrat is about long and wide, with roughly of coastline. It is n ...

where it was called Guardian International Bank. On 17 February 2009, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission charged Allen Stanford, Laura Pendergest-Holt

Laura Pendergest-Holt (born July 23, 1973) is a convicted Ponzi scheme perpetrator, financier, and former chief investment officer of Stanford Financial Group, who was charged with a civil charge of fraud on February 17, 2009. On May 12, 2009, Pen ...

and James Davis with fraud in connection with the bank's US$8 billion certificate of deposit

A certificate of deposit (CD) is a time deposit, a financial product commonly sold by banks, thrift institutions, and credit unions in the United States. CDs differ from savings accounts in that the CD has a specific, fixed term (often one, ...

(CD) investment scheme that offered "improbable and unsubstantiated high interest rates". This led the federal government to freeze the assets of the bank and other Stanford entities. On 27 February 2009, Pendergest-Holt was arrested by federal agents in connection with the alleged fraud. On that day, the SEC said that Stanford and his accomplices operated a "massive Ponzi scheme

A Ponzi scheme (, ) is a form of fraud that lures investors and pays profits to earlier investors with funds from more recent investors. Named after Italian businessman Charles Ponzi, the scheme leads victims to believe that profits are comin ...

", misappropriated billions of investors' money and falsified the Stanford International Bank's records to hide their fraud. "Stanford International Bank's financial statements, including its investment income, are fictional," the SEC said."New SEC Complaint Says Stanford Ran Ponzi Scheme"''

The Wall Street Journal

''The Wall Street Journal'' is an American business-focused, international daily newspaper based in New York City, with international editions also available in Chinese and Japanese. The ''Journal'', along with its Asian editions, is published ...

'', 27 February 2009.

Antigua Overseas Bank (AOB) was part of the ABI Financial Group and was a licensed bank in Antigua. On 13 April 2012, AOB was placed into receivership by the government of Antigua.

On 27 November 2018, Scotiabank

The Bank of Nova Scotia (french: link=no, Banque de Nouvelle-Écosse), operating as Scotiabank (french: link=no, Banque Scotia), is a Canadian multinational banking and financial services company headquartered in Toronto, Ontario. One of Canada ...

, the leading commercial bank on the island, announced plans to sell its banking operations in Antigua and 9 other non-core Caribbean markets to Republic Financial Holdings Limited.

Sport

The major Antiguan sport iscricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by st ...

. Vivian ("Viv") Richards is one of the most famous Antiguans, who played for, and captained, the West Indies cricket team

The West Indies cricket team, nicknamed the Windies, is a multi-national men's cricket team representing the mainly English-speaking countries and territories in the Caribbean region and administered by Cricket West Indies. The players on ...

. Richards scored the fastest Test century at the Antigua Recreation Ground

Antigua Recreation Ground is the national stadium of Antigua and Barbuda. It is located in St. John's, on the island of Antigua. The ground has been used by the West Indies cricket team and Antigua and Barbuda national football team. It had Tes ...

, it was also the venue at which Brian Lara

Brian Charles Lara, (born 2 May 1969) is a Trinidadian former international cricketer, widely acknowledged as one of the greatest batsmen of all time. He topped the Test batting rankings on several occasions and holds several cricketing rec ...

twice broke the world record for an individual Test innings (375 in 1993/94, 400 not out in 2003/04). Antigua was the location of a 2007 Cricket World Cup

The 2007 ICC Cricket World Cup was the ninth Cricket World Cup, a One Day International (ODI) cricket tournament that took place in the West Indies from 13 March to 28 April 2007. There were a total of 51 matches played, three fewer than at the ...

site, on a new Recreation Ground constructed on an old cane field in the north of the island. Both football (soccer) and basketball are becoming popular among the island youth. There are several golf courses in Antigua. Daniel Bailey

Daniel Bakka Everton Bailey (born 9 September 1986) is a sprinter from Antigua and Barbuda who specializes in the 100m.

Career

Bailey represented Antigua and Barbuda at the 2004 Summer Olympics, the 2006 Commonwealth Games, the 2008 Summer Ol ...

was the first athlete to win a global world medal at the 2010 IAAF World Indoor Championships

The 2010 IAAF World Indoor Championships in Athletics was held between 12 and 14 March at the Aspire Dome in Doha, Qatar. The championships was the first of six IAAF World Athletics Series events to take place in 2010.

Bidding and organisation ...

.

Being surrounded by water, sailing is one of the most popular sports with Antigua Sailing Week and Antigua Classic Yacht Regatta being two of the region's most reputable sailing competitions. Hundreds of yachts from around the world compete around Antigua each year. Sport fishing is also a very popular sport with several big competitions held yearly. Windsurfing was very popular until kite-surfing came to the island. Kitesurfing or kite-boarding is very popular at Jabbawock Beach.

Notable residents

*Curtly Ambrose

Sir Curtly Elconn Lynwall Ambrose KCN (born 21 September 1963) is an Antiguan former cricketer who played 98 Test matches for the West Indies. Widely acknowledged as one of the greatest fast bowlers of all time, he took 405 Test wickets ...

, legendary West-Indian cricketer

*Giorgio Armani

Giorgio Armani (; born 11 July 1934) is an Italian fashion designer. He first gained notoriety working for Cerruti and then for many others, including Allegri, Bagutta and Hilton. He formed his company, Armani, in 1975, which eventually expande ...

, Italian fashion designer; owns a home near Deep Bay

*Calvin Ayre

Calvin Edward Ayre (born May 25, 1961, in Lloydminster, Saskatchewan) is a Canadian- Antiguan entrepreneur based in Antigua and Barbuda. He is the founder of the Ayre Group and Bodog entertainment brand.

In 2000, Ayre launched online gambling ...

, billionaire founder of internet gambling company Bodog Entertainment Group

*Silvio Berlusconi

Silvio Berlusconi ( ; ; born 29 September 1936) is an Italian media tycoon and politician who served as Prime Minister of Italy in four governments from 1994 to 1995, 2001 to 2006 and 2008 to 2011. He was a member of the Chamber of Deputies f ...

, former Italian Prime Minister

*Richard Branson

Sir Richard Charles Nicholas Branson (born 18 July 1950) is a British billionaire, entrepreneur, and business magnate. In the 1970s he founded the Virgin Group, which today controls more than 400 companies in various fields.

Branson expressed ...

, Virgin Atlantic

Virgin Atlantic, a trading name of Virgin Atlantic Airways Limited and Virgin Atlantic International Limited, is a British airline with its head office in Crawley, England. The airline was established in 1984 as British Atlantic Airways, and ...

mogul

*Mehul Choksi

Mehul Chinubhai Choksi (born 5 May 1959) is a fugitive Indian-born businessman living in Antigua and Barbuda, who is wanted by the Indian judicial authorities for criminal conspiracy, criminal breach of trust, cheating and dishonesty including ...

, an Indian alleged scamster, diamond merchant and owner of Gitanjali Jewelers

*Eric Clapton

Eric Patrick Clapton (born 1945) is an English rock and blues guitarist, singer, and songwriter. He is often regarded as one of the most successful and influential guitarists in rock music. Clapton ranked second in ''Rolling Stone''s list o ...

, established an Antiguan drug treatment centre; has a home on the south of the island

*Melvin Claxton

Melvin L. Claxton (born 1958) is an American journalist, author, and entrepreneur. He has written about crime, corruption, and the abuse of political power. He is best known for his 1995 series of Investigative journalism, investigative reports ...

, Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made h ...

-winning journalist

*Timothy Dalton

Timothy Leonard Dalton Leggett (; born 21 March 1946) is a British actor. Beginning his career on stage, he made his film debut as Philip II of France in the 1968 historical drama ''The Lion in Winter''. He gained international prominence as ...

, actor of James Bond fame

* Heather Doram, artist, activist and educator, who designed the Antiguan and Barbudan national costume.

*Ken Follett

Kenneth Martin Follett, (born 5 June 1949) is a British author of thrillers and historical novels who has sold more than 160 million copies of his works.

Many of his books have achieved high ranking on best seller lists. For example, in the ...

, the author of '' Eye of the Needle'', owns a house on Jumby Bay

Long Island also known as Jumby Bay is an island off the northeast coast of Antigua. It is located off the northern tip of the Parham Peninsula, about from ''Dutchman Bay'' on Antigua. It is the fifth largest island of Antigua and Barbuda.

F ...

*Marie-Elena John

Marie-Elena John is a Caribbean writer whose novel, ''Unburnable'', was published in 2006. She is an Africanist, development and women’s rights specialist, currently serving as the Senior Racial Justice Lead at UN Women.

Biography

John was bor ...

, Antiguan writer and former African Development Foundation

The United States African Development Foundation (USADF) is an independent United States government agency that provides grants of up to $250,000 for operational assistance, enterprise expansion and market linkage to early stage agriculture, e ...

specialist. Her debut novel, ''Unburnable

''Unburnable'' is a 2006 novel written by Antiguan author Marie-Elena John and published by HarperCollins/Amistad. It is John's debut novel. Part historical fiction, murder mystery, and neo-slave narrative, ''Unburnable'' is a multi-generational ...

'', was selected Best Debut of 2006 by ''Black Issues Book Review

''Black Issues Book Review'' was a bimonthly magazine published in New York City, U.S., in which books of interest to African-American readers were reviewed. It was published from 1999 until 2007.

History and profile

''Black Issues Book Review'' ...

''

*S. D. Jones

Conrad Efraim (March 30, 1945 – October 26, 2008) was an Antiguan professional wrestler best known by his ring name, Special Delivery Jones or S. D. Jones (sometimes referred to as S. D. "Special Delivery" Jones) from his time (1974–1990) in ...

, professional wrestler known as "Special Delivery Jones" in the WWE

World Wrestling Entertainment, Inc., d/b/a as WWE, is an American professional wrestling promotion. A global integrated media and entertainment company, WWE has also branched out into other fields, including film, American football, and vario ...

in the 1970s and 1980s

*Phil Keoghan

Philip John Keoghan ( ; born 31 May 1967) is a New Zealand television personality, best known for hosting the American version of ''The Amazing Race'' on CBS, since its 2001 debut. He is the creator and host of ''No Opportunity Wasted'', whic ...

, host of ''The Amazing Race

''The Amazing Race'' is an adventure reality game show franchise in which teams of two people race around the world in competition with other teams. The ''Race'' is split into legs, with teams tasked to deduce clues, navigate themselves in forei ...

'', lived here during part of his childhood

*Jamaica Kincaid

Jamaica Kincaid (; born May 25, 1949) is an Antiguan-American novelist, essayist, gardener, and gardening writer. She was born in St. John's, Antigua (part of the twin-island nation of Antigua and Barbuda). She lives in North Bennington, Vermo ...

, novelist famous for her writings about life on Antigua. Her 1988 book '' A Small Place'' was banned under the Vere Bird administration

*Robin Leach

Robin Douglas Leach (29 August 1941 – 24 August 2018) was a British entertainment reporter and writer from London. After beginning his career as a print journalist, first in England and then in the United States, he became best known fo ...

of Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous

''Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous'' is an American television series that aired in syndication from 1984 to 1995. The show featured the extravagant lifestyles of wealthy entertainers, athletes, socialites and magnates.

It was hosted by Rob ...

fame.

* Archibald MacLeish, poet and (U.S.) Librarian of Congress.

* Rachel Lambert Mellon, horticulturist and philanthropist, has owned a compound in Antigua's Half Moon Bay since the 1950s.

*Fred Olsen

Fredrich Olsen (1891–1986) was a British-born American chemist remembered as the inventor of ball propellant and as a donor or seller to the art antiquities collections of Yale University, the University of Illinois, and the Massachusetts Insti ...

(1891–1986), inventor of the ball propellant

Ball propellant (trademarked as Ball Powder by Olin Corporation and marketed as spherical powder by Hodgdon Powder CompanyWootters, John ''Propellant Profiles'' (1982) Wolfe Publishing Company pp.95,101,136-138,141,149&155 ) is a form of nitrocell ...

manufacturing process

*Mary Prince

Mary Prince (c. 1 October 1788 – after 1833) was a British abolitionist and autobiographer, born in Bermuda to a slave family of African descent. After being sold a number of times, and being moved around the Caribbean, she was brought to Engl ...

, abolitionist and autobiographer, who wrote ''The History of Mary Prince'' (1831), the first account of the life of a Black woman to be published in the United Kingdom.

*Viv Richards

Sir Isaac Vivian Alexander Richards (born 7 March 1952) is an Antiguan retired cricketer who represented the West Indies cricket team between 1974 and 1991. Batting generally at number three in a dominant West Indies side, Richards is widely ...

, West Indian cricket legend; the Sir Vivian Richards Stadium in Antigua was named in his honour

*Richie Richardson

Sir Richard Benjamin Richardson, KCN (born 12 January 1962) is a former West Indies international cricketer and a former captain of the West Indian cricket team.

He was a flamboyant batsman and superb player of fast bowling. He was famous for ...

, former West-Indies cricket team captain

* Andy Roberts, the first Antiguan to play Test cricket for the West Indies. He was a member of the West Indies teams that won the 1975 and 1979 World Cups.

*Andriy Mykolayovych Shevchenko

Andriy Mykolayovych Shevchenko, or Andrii Mykolaiovych Shevchenko ( uk, Андрій Миколайович Шевченко, ; born 29 September 1976) is a Ukrainian football manager, a former professional football player and a former politici ...

, former Ukrainian footballer and politician.

*Peter Stringfellow

Peter James Stringfellow (17 October 1940 – 7 June 2018) was an English businessman who owned several nightclubs.

Early life

Stringfellow was born in the City General Hospital, Sheffield, South Yorkshire, on 17 October 1940, to Elsie Bowers a ...

, British nightclub owner

*Thomas J. Watson Jr.

Thomas John Watson Jr. (January 14, 1914 – December 31, 1993) was an American businessman, political figure, Army Air Forces pilot, and philanthropist. The son of IBM Corporation founder Thomas J. Watson, he was the second IBM president (195 ...

, CEO of IBM

*Oprah Winfrey

Oprah Gail Winfrey (; born Orpah Gail Winfrey; January 29, 1954), or simply Oprah, is an American talk show host, television producer, actress, author, and philanthropist. She is best known for her talk show, ''The Oprah Winfrey Show'', br ...

, talk-show host

See also

* Barbuda Land Acts * Bibliography of Antigua and Barbuda * Chief Justices *Geology of Antigua and Barbuda

The geology of Antigua and Barbuda is part of the Lesser Antilles volcanic island arc. Both islands are the above water limestone "caps" of now inactive volcanoes. The two islands are the surface features of the undersea Barbuda Bank and have karst ...

*Guns for Antigua

The Guns for Antigua scandal was a political scandal involving the shipment of Israeli-made weapons through Antigua to the Medellin drug cartel in Colombia. The affair was exposed by the Louis Blom-Cooper Royal Commission, following the discovery t ...

* Index of Antigua and Barbuda-related articles

*List of Antiguans and Barbudans

This a list of notable people from Antigua and Barbuda.

*DJ Red Alert, disc Jockey on Power 105.1 FM and has been recognized as a hip-hop pioneer

*Dee-Ann Kentish-Rogers, British-Anguillan Athlete, Barrister, Beauty Queen, Model and Politician ...

*Outline of Antigua and Barbuda

The following Outline (list), outline is provided as an overview of and introduction to Antigua and Barbuda:

Antigua and Barbuda – twin-island nation lying between the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. It consists of two major inhabite ...

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

Antigua Nice

(The Antigua Nice article was extracted by D.V. Nicholson's writings for the Antigua Historic Sites and Conservation Commission.)

*''The Life of Horatio Lord Nelson'' by

Robert Southey

Robert Southey ( or ; 12 August 1774 – 21 March 1843) was an English poet of the Romantic school, and Poet Laureate from 1813 until his death. Like the other Lake Poets, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Southey began as a ra ...

br>Project Gutenberg free book*The ''

Catholic Encyclopedia

The ''Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church'' (also referred to as the ''Old Catholic Encyclopedia'' and the ''Original Catholic Encyclopedia'') i ...

''

*''Veranda Magazine'', Island Flourish: West Indian Furnishings by Dana Micucci, March – April 2004

*''A Brief History of the Caribbean from the Arawak and the Carib to the Present'', by Jan Rogozinski, Penguin Putnam, Inc September 2000Article on Antiguan real estate.

Further reading

*External links

Government of Antigua and Barbuda

*

Embassy of Antigua and Barbuda in Madrid

- His Excellenc

Dr. Dario Item

is the Head of Mission.

Honorary Consulate General of Antigua and Barbuda in the Principality of Monaco

{{Authority control Islands of Antigua and Barbuda Former English colonies 1630s establishments in the Caribbean 1632 establishments in the British Empire 1632 establishments in North America