Anti-miscegenation Law In The United States on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In the United States,

In the United States,

Another case of interracial marriage was

Another case of interracial marriage was

"The Lawyer as Peacemaker: Law and Community in Abraham Lincoln's Slander Cases"

. The History Cooperative and

"Chinese Laborers in the West"

Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Program enacted such laws. While opposed to slavery, in a speech in Charleston, Illinois in 1858,

Filipino Resistance to Anti-Miscegenation Laws in Washington State

Great Depression in Washington State Project, 2009. *Johnson, Stefanie

Blocking Racial Intermarriage Laws in 1935 and 1937: Seattle's First Civil Rights Coalition

Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project, 2005. * *

Loving v. Virginia (No. 395) Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute

* ttp://www.lovingday.org Loving Day: Celebrate the Legalization of Interracial Couples

"The Socio-Political Context of the Integration of Sport in America", R. Reese, Cal Poly Pomona, ''Journal of African American Men'' (Volume 4, Number 3, Spring, 1999)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Anti-Miscegenation Laws in the United States 1660s establishments in the Thirteen Colonies 1967 disestablishments in the United States Race and law in the United States Race legislation in the United States Repealed United States legislation Politics and race in the United States African-American segregation in the United States Native American segregation in the United States Interracial marriage in the United States

anti-miscegenation laws

Anti-miscegenation laws or miscegenation laws are laws that enforce racial segregation at the level of marriage and intimate relationships by criminalization, criminalizing interracial marriage and sometimes also sex between members of different R ...

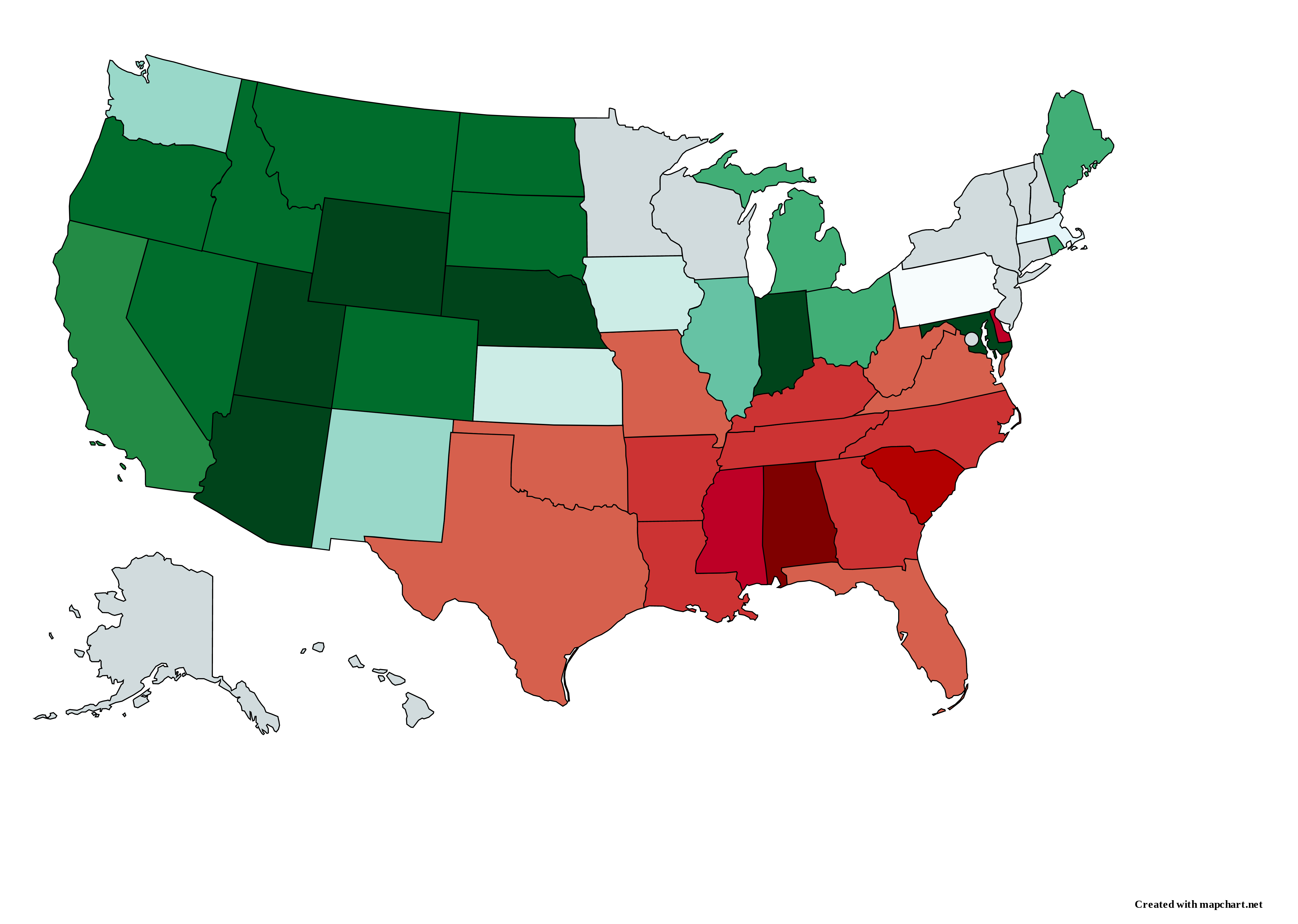

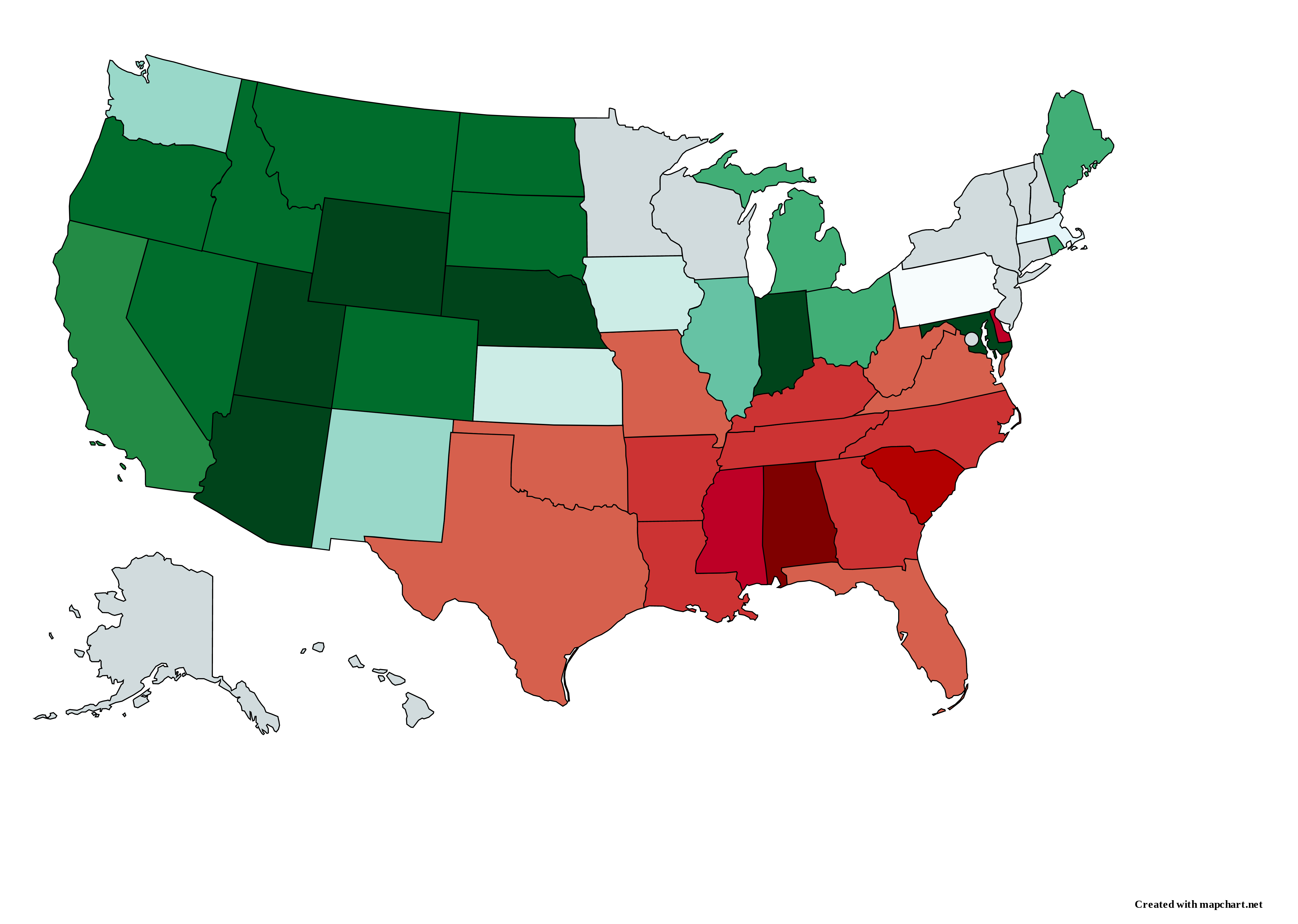

(also known as miscegenation laws) were laws passed by most states that prohibited interracial marriage, and in some cases also prohibited interracial sexual relations. Some such laws predate the establishment of the United States, some dating to the later 17th or early 18th century, a century or more after the complete racialization of slavery. Nine states never enacted such laws; 25 states had repealed their laws by 1967, when the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

ruled in ''Loving v. Virginia

''Loving v. Virginia'', 388 U.S. 1 (1967), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark civil rights decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that Anti-miscegenation laws in the United States, laws ban ...

'' that such laws were unconstitutional (via the 14th Amendment adopted in 1868) in the remaining 16 states. The term miscegenation was first used in 1863, during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, by journalists to discredit the abolitionist movement

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

by stirring up debate over the prospect of interracial marriage after the abolition of slavery.

Typically defining mixed-race marriages or sexual relations as a felony

A felony is traditionally considered a crime of high seriousness, whereas a misdemeanor is regarded as less serious. The term "felony" originated from English common law (from the French medieval word "félonie") to describe an offense that resu ...

, these laws also prohibited the issuance of marriage license

A marriage license (or marriage licence in Commonwealth spelling) is a document issued, either by a religious organization or state authority, authorizing a couple to marry. The procedure for obtaining a license varies between jurisdiction ...

s and the solemnization of weddings between mixed-race couples and prohibited the officiation of such ceremonies. Sometimes, the individuals attempting to marry would not be held guilty of miscegenation itself, but felony charges of adultery

Adultery (from Latin ''adulterium'') is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal ...

or fornication

Fornication is generally consensual sexual intercourse between two people not married to each other. When one or more of the partners having consensual sexual intercourse is married to another person, it is called adultery. Nonetheless, John ...

would be brought against them instead. All anti-miscegenation laws banned marriage between Whites and non-White groups, primarily Black people, but often also Native Americans and Asian Americans

Asian Americans are Americans of Asian ancestry (including naturalized Americans who are immigrants from specific regions in Asia and descendants of such immigrants). Although this term had historically been used for all the indigenous people ...

.

In many states, anti-miscegenation laws also criminalized cohabitation and sex between Whites and non-Whites. In addition, Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

in 1908 banned marriage "between a person of African descent" and "any person not of African descent"; Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

in 1920 banned marriage between Native Americans and African Americans (and from 1920 to 1942, concubinage as well); and Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

in 1935 banned marriages between Black people and Filipinos

Filipinos ( tl, Mga Pilipino) are the people who are citizens of or native to the Philippines. The majority of Filipinos today come from various Austronesian ethnolinguistic groups, all typically speaking either Filipino, English and/or othe ...

. While anti-miscegenation laws are often regarded as a Southern phenomenon, most states of the Western United States

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Far West, and the West) is the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the meaning of the term ''the Wes ...

and the Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, an ...

also enacted them.

Although anti-miscegenation amendments were proposed in United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

in 1871, 1912–1913 and 1928, a nationwide law against mixed-race marriages was never enacted. Prior to the California Supreme Court's ruling in ''Perez v. Sharp

''Perez v. Sharp'', also known as ''Perez v. Lippold'' or ''Perez v. Moroney'', is a 1948 case decided by the Supreme Court of California in which the court held by a 4–3 majority that the state's ban on interracial marriage violated the Fourte ...

'' (1948), no court in the United States had ever struck down a ban on interracial marriage. In 1967, the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

(the Warren Court) unanimously ruled in ''Loving v. Virginia

''Loving v. Virginia'', 388 U.S. 1 (1967), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark civil rights decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that Anti-miscegenation laws in the United States, laws ban ...

'' that anti-miscegenation laws are unconstitutional. After ''Loving'', the remaining state anti-miscegenation laws were repealed; the last state to repeal its laws against interracial marriage was Alabama in 2000.

Colonial era

The first laws criminalizing marriage and sex between Whites and non-Whites were enacted in the colonial era in the colonies ofVirginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

and Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, which depended economically on slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

.

At first, in the 1660s, the first laws in Virginia and Maryland regulating marriage between Whites and Black people only pertained to the marriages of Whites to Black (and mulatto

(, ) is a racial classification to refer to people of mixed African and European ancestry. Its use is considered outdated and offensive in several languages, including English and Dutch, whereas in languages such as Spanish and Portuguese is ...

) enslaved people and indentured servants. In 1664, Maryland criminalized such marriages—the 1681 marriage of Irish-born Nell Butler

Eleanor Butler (also known as Nell Butler or Irish Nell; born c. 1665) was an indentured white woman who married an enslaved African man in colonial Maryland in 1681.

Biography

Butler, who was of Irish origin, was an indentured servant to Charl ...

to an enslaved African man was an early example of the application of this law. The Virginian House of Burgesses

The House of Burgesses was the elected representative element of the Virginia General Assembly, the legislative body of the Colony of Virginia. With the creation of the House of Burgesses in 1642, the General Assembly, which had been established ...

passed a law in 1691 forbidding free Black people and Whites to intermarry, followed by Maryland in 1692. This was the first time in American history that a law was invented that restricted access to marriage partners solely on the basis of "race", not class or condition of servitude. Later these laws also spread to colonies with fewer enslaved and free Black people, such as Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

and Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

. Moreover, after the independence of the United States had been established, similar laws were enacted in territories and states which outlawed slavery.

A sizable number of the indentured servants in the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

were brought over from the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

by the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

. Anti-miscegenation laws discouraging interracial marriage between White American

White Americans are Americans who identify as and are perceived to be white people. This group constitutes the majority of the people in the United States. As of the 2020 Census, 61.6%, or 204,277,273 people, were white alone. This represented ...

s and non-Whites affected South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;;;;; ...

n immigrants as early as the 17th century. For example, a Eurasian

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelago ...

daughter born to an Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

father and Irish mother in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

in 1680 was classified as a "mulatto

(, ) is a racial classification to refer to people of mixed African and European ancestry. Its use is considered outdated and offensive in several languages, including English and Dutch, whereas in languages such as Spanish and Portuguese is ...

" and sold into slavery. Anti-miscegenation laws there continued into the early 20th century. For example, the Bengali

Bengali or Bengalee, or Bengalese may refer to:

*something of, from, or related to Bengal, a large region in South Asia

* Bengalis, an ethnic and linguistic group of the region

* Bengali language, the language they speak

** Bengali alphabet, the w ...

revolutionary Tarak Nath Das

Taraknath Das (or Tarak Nath Das; 15 June 1884 – 22 December 1958) was an Indian revolutionary and internationalist scholar. He was a pioneering immigrant in the west coast of North America and discussed his plans with Tolstoy, while organi ...

's White American wife, Mary Keatinge Morse, was stripped of her American citizenship for her marriage to an "alien

Alien primarily refers to:

* Alien (law), a person in a country who is not a national of that country

** Enemy alien, the above in times of war

* Extraterrestrial life, life which does not originate from Earth

** Specifically, intelligent extrater ...

ineligible for citizenship." In 1918, there was considerable controversy in Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

when an Indian farmer B. K. Singh married the sixteen-year-old daughter of one of his White tenants.

In 1685, the French government

The Government of France ( French: ''Gouvernement français''), officially the Government of the French Republic (''Gouvernement de la République française'' ), exercises executive power in France. It is composed of the Prime Minister, who ...

issued a special Code Noir restricted to colonial Louisiana

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 au ...

, which forbade marriage between Catholics and non-Catholics in that colony. However, interracial cohabitation and interracial sex were never prohibited in French Louisiana (see plaçage). The situation of the children (free or enslaved) followed the situation of the mother. Under Spanish rule, interracial marriage was possible with parental consent under the age of 25 and without it when the partners were older. In 1806, three years after the U.S. gained control over the state, interracial marriage was once again banned.

Jacqueline Battalora argues that the first laws banning all marriage between Whites and Black people, enacted in Virginia and Maryland, were a response by the planter elite to the problems they were facing due to the socio-economic dynamics of the plantation system in the Southern colonies. The bans in Virginia and Maryland were established at a time when slavery was not yet fully institutionalized. At the time, most forced laborers on the plantations were indentured servants, and they were mostly European. Some historians have suggested that the at-the-time unprecedented laws banning "interracial" marriage were originally invented by planters as a divide-and-rule tactic after the uprising of European and African indentured servants in cases such as Bacon's Rebellion. According to this theory, the ban on interracial marriage was issued to split up the ethnically mixed, increasingly "mixed-race" labor force into "Whites," who were given their freedom, and "blacks," who were later treated as slaves rather than as indentured servants. By outlawing "interracial" marriage, it became possible to keep these two new groups separated and prevent a new rebellion.

After independence

In 1776, seven of theThirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

enforced laws against interracial marriage. Although slavery was gradually abolished in the North after independence, this at first had little impact on the enforcement of anti-miscegenation laws. An exception was Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, which repealed its anti-miscegenation law in 1780, together with some of the other restrictions placed on free Black people, when it enacted a bill for the gradual abolition

Abolition refers to the act of putting an end to something by law, and may refer to:

* Abolitionism, abolition of slavery

* Abolition of the death penalty, also called capital punishment

* Abolition of monarchy

*Abolition of nuclear weapons

*Abol ...

of slavery in the state.

The Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

planter and slave trader Zephaniah Kingsley, Jr.

Zephaniah Kingsley Jr. (December 4, 1765 – September 14, 1843) was a Quaker, born in England, who moved as a child with his family to South Carolina, and became a Plantations in the American South, planter, History of slavery, slave trader, and ...

publicly advocated, and personally practiced, racial mixing as a way toward ending slavery, as well as a way to produce healthier and more beautiful offspring. These views were tolerated in Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida ( es, La Florida) was the first major European land claim and attempted settlement in North America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, ...

, where free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not ...

had rights and could own and inherit property. After Florida became a U.S. territory in 1821, he moved with his multiple "wives", children, and the people he enslaved, to Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

.

Another case of interracial marriage was

Another case of interracial marriage was Andrea Dimitry

Andrea Dimitry (January 1775 – March 1, 1852), also known as Andrea Drussakis Dimitry, was a Greek refugees, Greek refugee who migrated to New Orleans. He was a merchant and hero in the War of 1812. He married Marianne Celeste Dragon, Marianne C ...

and Marianne Céleste Dragon a free woman of African and European ancestry. Such marriages gave rise to a large creole community in New Orleans. She was listed as white on her marriage certificate. Marianne's father Don Miguel Dragon and mother Marie Françoise Chauvin Beaulieu de Monpliaisir also married in New Orleans Louisiana around 1815. Marie Françoise was a woman of African ancestry. Marie Françoise Chauvin de Beaulieu de Montplaisir was originally a slave of Mr. Charles Daprémont de La Lande, a member of the Superior Council.

For the radical abolitionists who organized to oppose slavery in the 1830s, laws banning interracial marriage embodied the same racial prejudice that they saw at the root of slavery. Abolitionist leader William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he found ...

took aim at Massachusetts' legal ban on interracial marriage as early as 1831. Anti-abolitionists defended the measure as necessary to prevent racial amalgamation and to maintain the Bay State's proper racial and moral order. Abolitionists, however, objected that the law, because it "distinguished between 'citizens on account of complexion,'" violated the broad egalitarian tenets of Christianity and republicanism as well as the state constitution's promise of equality. Beginning in the late 1830s, abolitionists began a several-year petition campaign that prompted the legislature to repeal the measure in 1843. Their efforts—both tactically and intellectually—constituted a foundational moment in the era's burgeoning minority-rights politics, which would continue to expand into the twentieth century. As the US expanded, however, all the new slave states as well as many new free states such as Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

Steiner, Mark"The Lawyer as Peacemaker: Law and Community in Abraham Lincoln's Slander Cases"

. The History Cooperative and

California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

enacted similar anti-miscegenation law"Chinese Laborers in the West"

Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Program enacted such laws. While opposed to slavery, in a speech in Charleston, Illinois in 1858,

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

stated, "I am not, nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people".

Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas, South Carolina and Alabama legalized interracial marriage for some years during the Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

period. Anti-miscegenation laws rested unenforced, were overturned by courts or repealed by the state government (in Arkansas and Louisiana). However, after white Democrats took power in the South during " Redemption", anti-miscegenation laws were re-enacted and once more enforced, and in addition Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

were enacted in the South which also enforced other forms of racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

. In Florida, the new Constitution of 1888 prohibited marriage between "a white person and a person of negro descent" (Article XVI, Section 24).

A number of northern and western states permanently repealed their anti-miscegenation laws during the 19th century. This, however, did little to halt anti-miscegenation sentiments in the rest of the country. Newly established western states continued to enact laws banning interracial marriage in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Between 1913 and 1948, 30 out of the then 48 states enforced anti-miscegenation laws. Only Connecticut, New Hampshire, New York, New Jersey, Vermont, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Alaska, Hawaii, and the District of Columbia

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

never enacted them.

''Pace v. Alabama''

The constitutionality of anti-miscegenation laws was upheld by theU.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

in the 1883 case ''Pace v. Alabama

''Pace v. Alabama'', 106 U.S. 583 (1883), was a case in which the United States Supreme Court affirmed that Alabama's anti-miscegenation statute was constitutional.. This ruling was rejected by the Supreme Court in 1964 in '' McLaughlin v. Flori ...

'' (106 U.S. 583). The Supreme Court ruled that the Alabama anti-miscegenation statute did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment (Amendment XIV) to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments. Often considered as one of the most consequential amendments, it addresses citizenship rights and ...

. According to the court, both races were treated equally, because whites and Black people were punished in equal measure for breaking the law against interracial marriage and interracial sex. This judgment was overturned in 1967 in the ''Loving v. Virginia

''Loving v. Virginia'', 388 U.S. 1 (1967), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark civil rights decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that Anti-miscegenation laws in the United States, laws ban ...

'' case, where the Supreme Court led by Chief Justice Earl Warren

Earl Warren (March 19, 1891 – July 9, 1974) was an American attorney, politician, and jurist who served as the 14th Chief Justice of the United States from 1953 to 1969. The Warren Court presided over a major shift in American constitution ...

declared anti-miscegenation laws a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment and therefore unconstitutional.

State v. Pass (Arizona 1942)

In State v. Pass, the Supreme Court of Arizona, interpreting the state's anti-miscegenation statute, ruled that persons of mixed racial heritage could not legally marry anyone. The court recognized that the result was absurd and expressed the hope that the legislature would amend the statute.Repeal of anti-miscegenation laws, 1948–1967

In 1948, the California Supreme Court ruled in ''Perez v. Sharp

''Perez v. Sharp'', also known as ''Perez v. Lippold'' or ''Perez v. Moroney'', is a 1948 case decided by the Supreme Court of California in which the court held by a 4–3 majority that the state's ban on interracial marriage violated the Fourte ...

'' (1948) that the Californian anti-miscegenation laws violated the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment (Amendment XIV) to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments. Often considered as one of the most consequential amendments, it addresses citizenship rights and ...

, the first time since Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

that a state court declared such laws unconstitutional, and making California the first state since Ohio in 1887 to overturn its anti-miscegenation law.

The case raised constitutional questions in states which had similar laws, which led to the repeal or overturning of such laws in fourteen states by 1967. Sixteen states, mainly Southern states, were the exception. In any case, in the 1950s, the repeal of anti-miscegenation laws was still a controversial issue in the U.S., even among supporters of racial integration

Racial integration, or simply integration, includes desegregation (the process of ending systematic racial segregation). In addition to desegregation, integration includes goals such as leveling barriers to association, creating equal opportunity ...

.

In 1958, the political theorist Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt (, , ; 14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) was a political philosopher, author, and Holocaust survivor. She is widely considered to be one of the most influential political theorists of the 20th century.

Arendt was born ...

, a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, who escaped from Europe during the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

, wrote in an essay in response to the Little Rock Crisis, the Civil Rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

struggle for the racial integration of public schools

Public school may refer to:

*State school (known as a public school in many countries), a no-fee school, publicly funded and operated by the government

*Public school (United Kingdom), certain elite fee-charging independent schools in England and ...

which took place in Little Rock, Arkansas

(The Little Rock, The "Little Rock")

, government_type = council-manager government, Council-manager

, leader_title = List of mayors of Little Rock, Arkansas, Mayor

, leader_name = Frank Scott Jr.

, leader_ ...

, in 1957, that anti-miscegenation laws were an even deeper injustice than the racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

of public schools. The free choice of a spouse, she argued in ''Reflections on Little Rock'', was "an elementary human right": "Even political rights, like the right to vote, and nearly all other rights enumerated in the Constitution, are secondary to the inalienable human rights to 'life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness' proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence; and to this category the right to home and marriage unquestionably belongs." Arendt was severely criticized by fellow liberals, who feared that her essay would arouse the racist fears common among whites and thus hinder the struggle of African Americans for civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

and racial integration

Racial integration, or simply integration, includes desegregation (the process of ending systematic racial segregation). In addition to desegregation, integration includes goals such as leveling barriers to association, creating equal opportunity ...

. Commenting on the Supreme Court's ruling in ''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segrega ...

'' against ''de jure'' racial segregation in education, Arendt argued that anti-miscegenation laws were more basic to racial segregation than racial segregation in education.

Arendt's analysis of the centrality of laws against interracial marriage to white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White su ...

echoed the conclusions of Gunnar Myrdal. In his essay ''Social Trends in America and Strategic Approaches to the Negro Problem'' (1948), Myrdal ranked the social areas where restrictions were imposed by Southern whites on the freedom of African-Americans through racial segregation from the least to the most important: jobs, courts and police, politics, basic public facilities, "social equality" including dancing and handshaking, and most importantly, marriage. This ranking was indeed reflective of the way in which the barriers against desegregation fell under the pressure of the protests of the emerging Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

. First, legal segregation in the army, in education and in basic public services fell, then restrictions on the voting rights of African-Americans were lifted. These victories were ensured by the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

. But the bans on interracial marriage were the last to go, in 1967.

Most Americans in the 1950s were opposed to interracial marriage and did not see laws banning interracial marriage as an affront to the principles of American democracy. A 1958 Gallup poll showed that 94% of Americans disapproved of interracial marriage. However, attitudes towards bans on interracial marriage quickly changed in the 1960s.

By the 1960s, civil rights organizations were helping interracial couples who were being penalized for their relationships to take their cases to the Supreme Court. Since ''Pace v. Alabama

''Pace v. Alabama'', 106 U.S. 583 (1883), was a case in which the United States Supreme Court affirmed that Alabama's anti-miscegenation statute was constitutional.. This ruling was rejected by the Supreme Court in 1964 in '' McLaughlin v. Flori ...

'' (1883), the Supreme Court had declined to make a judgment in such cases. But in 1964, the Warren Court decided to issue a ruling in the case of an interracial couple from Florida who had been convicted because they had been cohabiting

Cohabitation is an arrangement where people who are not married, usually couples, live together. They are often involved in a romantic or sexually intimate relationship on a long-term or permanent basis. Such arrangements have become increas ...

. In ''McLaughlin v. Florida

''McLaughlin v. Florida'', 379 U.S. 184 (1964), was a case in which the United States Supreme Court ruled unanimously that a cohabitation law of Florida, part of the state's anti-miscegenation laws, was unconstitutional. The law prohibited habitu ...

'', the Supreme Court ruled that the Florida state law which prohibited cohabitation between whites and non-whites was unconstitutional and based solely on a policy of racial discrimination

Racial discrimination is any discrimination against any individual on the basis of their skin color, race or ethnic origin.Individuals can discriminate by refusing to do business with, socialize with, or share resources with people of a certain g ...

. However, the court did not rule on Florida's ban on marriage between whites and non-whites, despite the appeal of the plaintiffs to do so and the argument made by the state of Florida that its ban on cohabitation between whites and blacks was ancillary to its ban on marriage between whites and blacks. However, in 1967, the court did decide to rule on the remaining anti-miscegenation laws when it was presented with the case of ''Loving v. Virginia

''Loving v. Virginia'', 388 U.S. 1 (1967), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark civil rights decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that Anti-miscegenation laws in the United States, laws ban ...

''.

''Loving v. Virginia''

In 1967, an interracial couple, Richard and Mildred Loving, successfully challenged the constitutionality of the ban on interracial marriage inVirginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

. Their case reached the US Supreme Court as ''Loving v. Virginia''.

In 1958, the Lovings married in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

to evade Virginia's anti-miscegenation law (the Racial Integrity Act

In 1924, the Virginia General Assembly enacted the Racial Integrity Act. The act reinforced racial segregation by prohibiting interracial marriage and classifying as "white" a person "who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian ...

). On their return to Virginia, they were arrested in their bedroom for living together as an interracial couple. The judge suspended their sentence on the condition that the Lovings leave Virginia and not return for 25 years. In 1963, the Lovings, who had moved to Washington, D.C, decided to appeal this judgment. In 1965, Virginia trial court Judge Leon Bazile, who heard their original case, refused to reconsider his decision. Instead, he defended racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

, writing:

The Lovings then took their case to the Supreme Court of Virginia

The Supreme Court of Virginia is the highest court in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It primarily hears direct appeals in civil cases from the trial-level city and county circuit courts, as well as the criminal law, family law and administrative ...

, which invalidated the original sentence but upheld the state's Racial Integrity Act

In 1924, the Virginia General Assembly enacted the Racial Integrity Act. The act reinforced racial segregation by prohibiting interracial marriage and classifying as "white" a person "who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian ...

.

Finally, the Lovings turned to the U.S Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point of ...

. The court, which had previously avoided taking miscegenation cases, agreed to hear an appeal. In 1967, 84 years after ''Pace v. Alabama

''Pace v. Alabama'', 106 U.S. 583 (1883), was a case in which the United States Supreme Court affirmed that Alabama's anti-miscegenation statute was constitutional.. This ruling was rejected by the Supreme Court in 1964 in '' McLaughlin v. Flori ...

'' in 1883, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the anti-miscegenation laws were unconstitutional. Chief Justice Warren wrote in the court majority opinion that:

The Supreme Court condemned Virginia's anti-miscegenation law as "designed to maintain White Supremacy".

Later events

In 1967, 17 Southern states plus Oklahoma still enforced laws prohibiting marriage between whites and non-whites. Maryland repealed its law at the start of ''Loving v. Virginia'' in the Supreme Court. After the Supreme Court ruling declaring such laws to be unconstitutional, the laws in the remaining 16 states ceased to be enforceable. Even so, it was necessary for theSupreme Court of Florida

The Supreme Court of Florida is the highest court in the U.S. state of Florida. It consists of seven members: the chief justice and six justices. Six members are chosen from six districts around the state to foster geographic diversity, and one ...

to issue a Writ Of Mandamus compel a Dade County judge to issue a marriage license to an interracial couple. Two Justices of the court dissented from the issuance of the writ. Besides removing such laws from their statute books, a number of state constitutions were also amended to remove language prohibiting miscegenation: Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

in 1969, Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

in 1987, South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

in 1998, and Alabama in 2000. In the respective referendums, 52% of voters in Mississippi, 62% of voters in South Carolina and 59% of voters in Alabama voted in favor of the amendments. In Alabama, nearly 526,000 people voted against the amendment, including a majority of voters in some rural counties.

Three months after ''Loving v. Virginia'', "Storybook Children" sung by Billy Vera and Judy Clay became the first romantic interracial duet to chart in the US.

In 2009, Keith Bardwell

Keith may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Keith (given name), includes a list of people and fictional characters

* Keith (surname)

* Keith (singer), American singer James Keefer (born 1949)

* Baron Keith, a line of Scottish barons i ...

, a justice of the peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

in Robert, Louisiana

Robert is an unincorporated community in Tangipahoa Parish, Louisiana, United States. It lies east of Hammond, at the intersection of US 190 and LA 445, from which it has a signed exit on Interstate 12. Robert is the largest settlement in Tangi ...

, refused to officiate a civil wedding

A wedding is a ceremony where two people are united in marriage. Wedding traditions and customs vary greatly between cultures, ethnic groups, religions, countries, and social classes. Most wedding ceremonies involve an exchange of marriag ...

for an interracial couple. A nearby justice of the peace, on Bardwell's referral, officiated the wedding; the interracial couple sued Keith Bardwell and his wife Beth Bardwell in federal court. After facing wide criticism for his actions, including from Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal

Piyush "Bobby" Jindal (born June 10, 1971) is an American politician who served as the 55th Governor of Louisiana from 2008 to 2016. The only living former Louisiana governor, Jindal also served as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives a ...

, Bardwell resigned on November 3, 2009.

, seven states still required couples to declare their racial background when applying for a marriage license, without which they cannot marry. The states are Connecticut, Delaware, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota (since 1977), New Hampshire, and Alabama. In 2019 in Virginia, a law that required partners to declare their race on marriage applications was challenged in court. Within a week the state's Attorney-General directed that the question is to become optional, and in October 2019, a U.S. District judge ruled the practice unconstitutional and barred Virginia from enforcing the requirement.

In 2016, Mississippi passed a law to protect "sincerely held religious beliefs or moral convictions". In September 2019, an owner of a wedding venue in Mississippi refused to allow a mixed race wedding to take place in the venue, claiming the refusal was based on her Christian beliefs. After an outcry on social media and after consulting with her pastor, the owner apologized to the couple.

Summary

Laws repealed through 1887

Laws repealed 1948–1967

Laws overturned on June 12, 1967, by ''Loving v. Virginia''

Proposed constitutional amendments

At least three attempts have been made to amend the US constitution to bar interracial marriage in the United States. * In 1871, Representative Andrew King, aDemocrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

of Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

, proposed a nationwide ban on interracial marriage. King proposed the amendment because he feared that the Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868 to give ex-slaves citizenship (the Freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...

) as part of the process of Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

, would someday render laws against interracial marriage unconstitutional, as it eventually did.

* In December 1912 and January 1913, Representative Seaborn Roddenbery, a Democrat of Georgia, introduced a proposal in the House of Representatives to insert a prohibition of miscegenation into the US Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the nation ...

. According to the wording of the proposed amendment, "Intermarriage between Negroes or persons of color and Caucasians... within the United States... is forever prohibited." Roddenbery's proposal was more severe because it defined the racial boundary between whites and "persons of color" by applying the one-drop rule. In his proposed amendment, anyone with "any trace of African or Negro blood" was banned from marrying a white spouse.

:Roddenbery's proposed amendment was a direct reaction to African American heavyweight boxer Jack Johnson's marriages to white women, first to Etta Duryea and then to Lucille Cameron. In 1908, Johnson had become the first black boxing world champion, having beaten Tommy Burns. After his victory, the search was on for a white boxer, a "Great White Hope", to beat Johnson. Those hopes were dashed in 1910, when Johnson beat former world champion Jim Jeffries. This victory ignited race riots across America as frustrated whites attacked celebrating African Americans. Johnson's marriages to and affairs with white women infuriated some Americans, mostly white. In his speech introducing his bill before the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

, Roddenbery compared the marriage of Johnson and Cameron to the enslavement of white women, and warned of future civil war that would ensue if interracial marriage was not made illegal nationwide:

:Roddenbery's proposal of the anti-miscegenation amendment unleashed a wave of racialist

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies can be more e ...

support for the move: 19 states that lacked such laws proposed their enactment. In 1913, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

, which had abolished its anti-miscegenation law in 1843, enacted a measure

Measure may refer to:

* Measurement, the assignment of a number to a characteristic of an object or event

Law

* Ballot measure, proposed legislation in the United States

* Church of England Measure, legislation of the Church of England

* Mea ...

(not repealed until 2008)) that prevented couples who could not marry in their home state from marrying in Massachusetts.

* In 1928, Senator Coleman Blease, a Democrat of South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, proposed an amendment that went beyond the previous ones, requiring that Congress set a punishment for interracial couples attempting to get married and for people officiating an interracial marriage. This amendment was also never enacted.

See also

* Interracial marriage in the United States * ''Guess Who's Coming to Dinner

''Guess Who's Coming to Dinner'' is a 1967 American romantic comedy-drama film produced and directed by Stanley Kramer, and written by William Rose. It stars Spencer Tracy (in his final role), Sidney Poitier, and Katharine Hepburn, and featur ...

''

References

Further reading (most recent first)

* * * Pascoe, Peggy. ''What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America''. Oxford University Press, 2009. *Strandjord, CorinneFilipino Resistance to Anti-Miscegenation Laws in Washington State

Great Depression in Washington State Project, 2009. *Johnson, Stefanie

Blocking Racial Intermarriage Laws in 1935 and 1937: Seattle's First Civil Rights Coalition

Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project, 2005. * *

External links

Loving v. Virginia (No. 395) Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute

* ttp://www.lovingday.org Loving Day: Celebrate the Legalization of Interracial Couples

"The Socio-Political Context of the Integration of Sport in America", R. Reese, Cal Poly Pomona, ''Journal of African American Men'' (Volume 4, Number 3, Spring, 1999)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Anti-Miscegenation Laws in the United States 1660s establishments in the Thirteen Colonies 1967 disestablishments in the United States Race and law in the United States Race legislation in the United States Repealed United States legislation Politics and race in the United States African-American segregation in the United States Native American segregation in the United States Interracial marriage in the United States