Anti-Japanese Sentiment In Taiwan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anti-Japanese sentiment (also called Japanophobia, Nipponophobia and anti-Japanism) involves the hatred or fear of anything which is Japanese, be it its

(visitado em 17 de agosto de 2008) On 22 October 1923, Representative Fidélis Reis produced a bill on the entry of immigrants, whose fifth article was as follows: "The entry of settlers from the black race into Brazil is prohibited. For Asian mmigrantsthere will be allowed each year a number equal to 5% of those residing in the country...."RIOS, Roger Raupp. Text excerpted from a judicial sentence concerning crime of racism. Federal Justice of 10ª Vara da Circunscrição Judiciária de Porto Alegre

, 16 November 2001] (Accessed 10 September 2008) Years before World War II, the government of President Getúlio Vargas initiated a process of forced assimilation of people of immigrant origin in Brazil. In 1933, a constitutional amendment was approved by a large majority and established immigration quotas without mentioning race or nationality and prohibited the population concentration of immigrants. According to the text, Brazil could not receive more than 2% of the total number of entrants of each nationality that had been received in the last 50 years. Only the Portuguese were excluded. The measures did not affect the immigration of Europeans such as Italians and Spaniards, who had already entered in large numbers and whose migratory flow was downward. However, immigration quotas, which remained in force until the 1980s, restricted Japanese immigration, as well as Korean and Chinese immigration. When Brazil sided with the

Anti-Japanese sentiment is felt very strongly in China and distrust, hostility and negative feelings towards Japan and the Japanese people and culture is widespread in China. Anti-Japanese sentiment is a phenomenon that mostly dates back to modern times (since 1868). Like many Western powers during the era of imperialism, Japan negotiated treaties that often resulted in the annexation of land from China towards the end of the

Anti-Japanese sentiment is felt very strongly in China and distrust, hostility and negative feelings towards Japan and the Japanese people and culture is widespread in China. Anti-Japanese sentiment is a phenomenon that mostly dates back to modern times (since 1868). Like many Western powers during the era of imperialism, Japan negotiated treaties that often resulted in the annexation of land from China towards the end of the

Anti-Japanese sentiment in the Philippines can be traced back to the Japanese occupation of the country during World War II and its aftermath. An estimated 1 million Filipinos out of a wartime population of 17 million were killed during the war, and many more Filipinos were injured. Nearly every Filipino family was affected by the war on some level. Most notably, in the city of Mapanique, survivors have recounted the Japanese occupation during which Filipino men were massacred and dozens of women were herded in order to be used as

Anti-Japanese sentiment in the Philippines can be traced back to the Japanese occupation of the country during World War II and its aftermath. An estimated 1 million Filipinos out of a wartime population of 17 million were killed during the war, and many more Filipinos were injured. Nearly every Filipino family was affected by the war on some level. Most notably, in the city of Mapanique, survivors have recounted the Japanese occupation during which Filipino men were massacred and dozens of women were herded in order to be used as

The

The

The most profound cause of anti-Japanese sentiment outside of Asia started by the Japanese

The most profound cause of anti-Japanese sentiment outside of Asia started by the Japanese  An estimated 112,000 to 120,000 Japanese migrants and

An estimated 112,000 to 120,000 Japanese migrants and

ar/nowiki> was necessary in order for us to protect the independence of Japan and to prosper together with our Asian neighbors" and that the war criminals were "cruelly and unjustly tried as war criminals by a sham-like tribunal of the Allied forces". While it is true that the fairness of these trials is disputed among jurists and historians in the West as well as in Japan, the former

online

* MacArthur, Brian. ''Surviving the Sword: Prisoners of the Japanese in the Far East, 1942-45'' (Random House, 2005). * Maga, Timothy P. ''Judgment at Tokyo: the Japanese war crimes trials'' (University Press of Kentucky, 2001). * Monahan, Evelyn, and Rosemary Neidel-Greenlee. ''All this hell: US nurses imprisoned by the Japanese'' (University Press of Kentucky, 2000). * * Nie, Jing-Bao. "The United States cover-up of Japanese wartime medical atrocities: Complicity committed in the national interest and two proposals for contemporary action." ''American Journal of Bioethics'' 6.3 (2006): W21-W33. * * * Tanaka, Yuki, and John W. Dower. ''Hidden horrors: Japanese war crimes in World War II'' (Routledge, 2019). * * Totani, Yuma. ''The Tokyo War Crimes Trial: The Pursuit of Justice in the Wake of World War II'' (Harvard University Asia Center Publications Program, 2008

online review

* Tsuchiya, Takashi. "The imperial Japanese experiments in China." in ''The Oxford textbook of clinical research ethics'' (2008) pp: 31-45. * Twomey, Christina. "Double displacement: Western women's return home from Japanese internment in the Second World War." ''Gender & History'' 21.3 (2009): 670-684. focus on British women * * Yap, Felicia. "Prisoners of war and civilian internees of the Japanese in British Asia: the similarities and contrasts of experience." ''Journal of Contemporary History'' 47.2 (2012): 317-346. * *{{cite book, title= Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië, Volume 129 , others=Contributor Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (Netherlands), year=1973, publisher=M. Nijhoff, url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LpJuAAAAMAAJ, access-date=10 March 2014

The Impact of Asian-Pacific Migration on U.S. Immigration Policy

*Kahn, Joseph

''The New York Times''. 15 April 2005

culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.Tyl ...

or its people

A person (plural, : people) is a being that has certain capacities or attributes such as reason, morality, consciousness or self-consciousness, and being a part of a culturally established form of social relations such as kinship, ownership of pr ...

. Its opposite is Japanophilia

Japanophilia is the philia of Japanese culture, people and history. In Japanese, the term for Japanophile is , with "" equivalent to the English prefix 'pro-' and "", meaning "Japan" (as in the word for Japan ). The term was first used as ea ...

.

Overview

Anti-Japanese sentiments range fromanimosity

Animosity may refer to:

* ''Animosity'' (comic), an American comic book series published by AfterShock Comics

*Animosity (band)

Animosity was an American death metal band from San Francisco, California, formed in 2000. The band released three ...

towards the Japanese government

The Government of Japan consists of legislative, executive and judiciary branches and is based on popular sovereignty. The Government runs under the framework established by the Constitution of Japan, adopted in 1947. It is a unitary state, c ...

's actions and disdain

Contempt is a pattern of attitudes and behaviour, often towards an individual or a group, but sometimes towards an ideology, which has the characteristics of disgust and anger.

The word originated in 1393 in Old French contempt, contemps, ...

for Japanese culture to racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

against the Japanese people

The are an East Asian ethnic group native to the Japanese archipelago."人類学上は,旧石器時代あるいは縄文時代以来,現在の北海道〜沖縄諸島(南西諸島)に住んだ集団を祖先にもつ人々。" () Jap ...

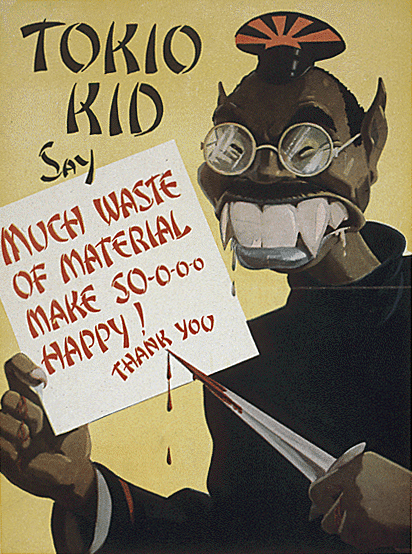

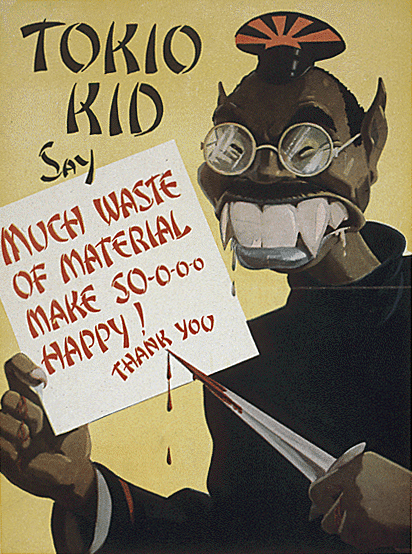

. Sentiments of dehumanization

Dehumanization is the denial of full humanness in others and the cruelty and suffering that accompanies it. A practical definition refers to it as the viewing and treatment of other persons as though they lack the mental capacities that are c ...

have been fueled by the anti-Japanese propaganda of the Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

governments in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

; this propaganda was often of a racially disparaging character. Anti-Japanese sentiment may be strongest in Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, due to atrocities committed by the Japanese military.

In the past, anti-Japanese sentiment contained innuendos of Japanese people as barbaric

A barbarian (or savage) is someone who is perceived to be either uncivilized or primitive. The designation is usually applied as a generalization based on a popular stereotype; barbarians can be members of any nation judged by some to be less c ...

. Following the Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

of 1868, Japan was intent to adopt Western ways in an attempt to join the West as an industrialized imperial power, but a lack of acceptance of the Japanese in the West complicated integration and assimilation. One commonly held view was that the Japanese were "evolutionarily inferior" . Japanese culture was viewed with suspicion and even disdain.

While passions have settled somewhat since Japan's surrender in World War II, tempers continue to flare on occasion over the widespread perception that the Japanese government has made insufficient penance for their past atrocities, or has sought to whitewash the history of these events. Today, though the Japanese government has effected some compensatory measures, anti-Japanese sentiment continues based on historical and nationalist animosities linked to Imperial Japanese

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent forma ...

military aggression

A war of aggression, sometimes also war of conquest, is a military conflict waged without the justification of self-defense, usually for territorial gain and subjugation.

Wars without international legality (i.e. not out of self-defense nor sanc ...

and atrocities. Japan's delay in clearing more than 700,000 (according to the Japanese Government) pieces of life-threatening and environment contaminating chemical weapons

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized Ammunition, munition that uses chemicals chemical engineering, formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be an ...

buried in China at the end of World War II is another cause of anti-Japanese sentiment.

Periodically, individuals within Japan spur external criticism. Former Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi

Junichiro Koizumi (; , ''Koizumi Jun'ichirō'' ; born 8 January 1942) is a former Japanese politician who was Prime Minister of Japan and President of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) from 2001 to 2006. He retired from politics in 2009. He is ...

was heavily criticized by South Korea and China for annually paying his respects to the war dead at Yasukuni Shrine

is a Shinto shrine located in Chiyoda, Tokyo. It was founded by Emperor Meiji in June 1869 and commemorates those who died in service of Empire of Japan, Japan, from the Boshin War of 1868–1869, to the two Sino-Japanese Wars, First Sino-Japane ...

, which enshrines all those who fought and died for Japan during World War II, including 1,068 convicted war criminals. Right-wing nationalist groups have produced history textbooks whitewashing Japanese atrocities, and the recurring controversies over these books occasionally attract hostile foreign attention.

Some anti-Japanese sentiment originates from business practices used by some Japanese companies, such as dumping.

By region

Australia

InAustralia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

, the White Australia policy

The White Australia policy is a term encapsulating a set of historical policies that aimed to forbid people of non-European ethnic origin, especially Asians (primarily Chinese) and Pacific Islanders, from immigrating to Australia, starting i ...

was partly inspired by fears in the late 19th century that if large numbers of Asian immigrants were allowed, they would have a severe and adverse effect on wages, the earnings of small business people, and other elements of the standard of living. Nevertheless, a significant numbers of Japanese immigrants arrived in Australia prior to 1900, perhaps most significantly in the town of Broome. By the late 1930s, Australians feared that Japanese military strength might lead to expansion in Southeast Asia and the Pacific and perhaps even an invasion of Australia itself. That resulted in a ban on iron ore

Iron ores are rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be economically extracted. The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty red. The iron is usually found in the fo ...

exports to the Empire of Japan, from 1938.

During World War II, atrocities were frequently committed to Australians who surrendered (or attempted to surrender) to Japanese soldiers, most famously the ritual beheading of Leonard Siffleet

Leonard George Siffleet (14 January 1916 – 24 October 1943) was an Australian commando of World War II. Born in Gunnedah, New South Wales, he joined the Second Australian Imperial Force in 1941, and by 1943 had reached the rank of ...

, which was photographed, and incidents of cannibalism and the shooting down of ejected pilots' parachutes. Anti-Japanese feelings were particularly provoked by the sinking of the unarmed Hospital Ship ''Centaur'' (painted white and with Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

markings), with 268 dead. The treatment of Australians prisoners of war was also a factor, with over 2,800 Australian POWs dying on the Burma Railway

The Burma Railway, also known as the Siam–Burma Railway, Thai–Burma Railway and similar names, or as the Death Railway, is a railway between Ban Pong, Thailand and Thanbyuzayat, Burma (now called Myanmar). It was built from 1940 to 1943 ...

alone.

Brazil

Like the elites inArgentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

and Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

, the Brazilian elite wanted to racially whiten the country's population during the 19th and 20th centuries. The country's governments always encouraged European immigration, but non-white immigration was always greeted with considerable opposition. The communities of Japanese immigrants were seen as an obstacle to the whitening of Brazil and they were also seen, among other concerns, as being particularly tendentious because they formed ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished t ...

s and they also practiced endogamy

Endogamy is the practice of marrying within a specific social group, religious denomination, caste, or ethnic group, rejecting those from others as unsuitable for marriage or other close personal relationships.

Endogamy is common in many cultu ...

at a high rate. Oliveira Viana, a Brazilian jurist, historian, and sociologist, described the Japanese immigrants as follows: "They (Japanese) are like sulfur: insoluble." The Brazilian magazine ''O Malho

''O Malho'' (Portuguese: ''The Mallet'') was a Brazilian weekly satirical magazine published from 1902 to 1954. It was based in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. It was the first commercially successful Brazilian satirical magazine during the Republican re ...

'' in its edition of 5 December 1908, issued a charge of Japanese immigrants with the following legend: "The government of São Paulo

São Paulo (, ; Portuguese for 'Saint Paul') is the most populous city in Brazil, and is the capital of the state of São Paulo, the most populous and wealthiest Brazilian state, located in the country's Southeast Region. Listed by the GaWC a ...

is stubborn. After the failure of the first Japanese immigration, it contracted 3,000 yellow people. It insists on giving Brazil a race diametrically opposite to ours."SUZUKI Jr, Matinas. História da discriminação brasileira contra os japoneses sai do limbo ''in'' Folha de S.Paulo, 20 de abril de 2008(visitado em 17 de agosto de 2008) On 22 October 1923, Representative Fidélis Reis produced a bill on the entry of immigrants, whose fifth article was as follows: "The entry of settlers from the black race into Brazil is prohibited. For Asian mmigrantsthere will be allowed each year a number equal to 5% of those residing in the country...."RIOS, Roger Raupp. Text excerpted from a judicial sentence concerning crime of racism. Federal Justice of 10ª Vara da Circunscrição Judiciária de Porto Alegre

, 16 November 2001] (Accessed 10 September 2008) Years before World War II, the government of President Getúlio Vargas initiated a process of forced assimilation of people of immigrant origin in Brazil. In 1933, a constitutional amendment was approved by a large majority and established immigration quotas without mentioning race or nationality and prohibited the population concentration of immigrants. According to the text, Brazil could not receive more than 2% of the total number of entrants of each nationality that had been received in the last 50 years. Only the Portuguese were excluded. The measures did not affect the immigration of Europeans such as Italians and Spaniards, who had already entered in large numbers and whose migratory flow was downward. However, immigration quotas, which remained in force until the 1980s, restricted Japanese immigration, as well as Korean and Chinese immigration. When Brazil sided with the

Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

and declared war to Japan in 1942, all communication with Japan was cut off, the entry of new Japanese immigrants was forbidden, and many restrictions affected the Japanese Brazilians. Japanese newspapers and teaching the Japanese language in schools were banned, which left Portuguese as the only option for Japanese descendants. As many Japanese immigrants could not understand Portuguese, it became exceedingly difficult for them to obtain any extra-communal information. In 1939, research of Estrada de Ferro Noroeste do Brasil

Rail transport in Brazil began in the 19th century and there were many different railway companies. The railways were nationalised under RFFSA (Rede Ferroviária Federal, Sociedade Anônima) in 1957. Between 1999 and 2007, RFFSA was broken u ...

in São Paulo showed that 87.7% of Japanese Brazilians read newspapers in the Japanese language, a much higher literacy

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in written form in some specific context of use. In other words, huma ...

rate than the general populace at the time. Japanese Brazilians could not travel without safe conduct

Safe conduct, safe passage, or letters of transit, is the situation in time of international conflict or war where one state, a party to such conflict, issues to a person (usually an enemy state's subject) a pass or document to allow the enemy ...

issued by the police, Japanese schools were closed, and radio receivers was confiscated to prevent transmissions on shortwave

Shortwave radio is radio transmission using shortwave (SW) radio frequencies. There is no official definition of the band, but the range always includes all of the high frequency band (HF), which extends from 3 to 30 MHz (100 to 10 me ...

from Japan. The goods of Japanese companies were confiscated and several companies of Japanese origin had interventions by the government. Japanese Brazilians were prohibited from driving motor vehicles, and the drivers employed by Japanese had to have permission from the police. Thousands of Japanese immigrants were arrested or deported

Deportation is the expulsion of a person or group of people from a place or country. The term ''expulsion'' is often used as a synonym for deportation, though expulsion is more often used in the context of international law, while deportation ...

from Brazil on suspicion of espionage. On 10 July 1943, approximately 10,000 Japanese and German and Italian immigrants who lived in Santos had 24 hours to move away from the Brazilian coast. The police acted without any notice. About 90% of people displaced were Japanese. To reside in coastal areas, the Japanese had to have a safe conduct. In 1942, the Japanese community who introduced the cultivation of pepper in Tomé-Açu, in Pará

Pará is a Federative units of Brazil, state of Brazil, located in northern Brazil and traversed by the lower Amazon River. It borders the Brazilian states of Amapá, Maranhão, Tocantins (state), Tocantins, Mato Grosso, Amazonas (Brazilian state) ...

, was virtually turned into a "concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

". his time, the Brazilian ambassador in Washington, DC, Carlos Martins Pereira e Sousa, encouraged the government of Brazil to transfer all Japanese Brazilians to "internment camps" without the need for legal support, just as was done with the Japanese residents in the United States. However, no suspicion of activities of Japanese against "national security" was ever confirmed.

Even after the war ended, anti-Japanese sentiment persisted in Brazil. After the war, Shindo Renmei, a terrorist organization formed by Japanese immigrants that murdered Japanese-Brazilians who believed in Japanese surrender

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy ...

, was founded. The violence acts committed by this organization increased anti-Japanese sentiment in Brazil and caused several violent conflicts between Brazilians and Japanese-Brazilians. During the National Constituent Assembly of 1946, the representative of Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

Miguel Couto Filho proposed an amendment to the Constitution saying "It is prohibited the entry of Japanese immigrants of any age and any origin in the country." In the final vote, a tie with 99 votes in favour and 99 against. Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

Fernando de Melo Viana

Fernando de Melo Viana (15 March 1878 – 10 February 1954) was a Brazil, Brazilian politician who was the 11th vice president of Brazil from 15 November 1926 to 24 October 1930 serving under President Washington Luís. As vice president, he al ...

, who chaired the session of the Constituent Assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

, had the casting vote and rejected the constitutional amendment. By only one vote, the immigration of Japanese people to Brazil was not prohibited by the Brazilian Constitution of 1946.

In the second half of the 2010s, a certain anti-Japanese feeling has grown in Brazil. The current Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro

Jair Messias Bolsonaro (; born 21 March 1955) is a Brazilian politician and retired military officer who has been the 38th president of Brazil since 1 January 2019. He was elected in 2018 as a member of the Social Liberal Party, which he turn ...

, was accused of making statements considered discriminatory against Japanese people, which generated repercussions in the press and in the Japanese-Brazilian community, which is considered the largest in the world outside of Japan. In addition, in 2020, possibly as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is an ongoing global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The novel virus was first identif ...

, some incidents of xenophobia and abuse were reported to Japanese-Brazilians in cities such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

Canada

Like other countries which Japanese immigrated to in significant numbers, anti-Japanese sentiment in Canada was strongest during the 20th century, with the formation of anti-immigration organizations such as theAsiatic Exclusion League

The Asiatic Exclusion League (often abbreviated AEL) was an organization formed in the early 20th century in the United States and Canada that aimed to prevent immigration of people of Asian origin.

United States

In May 1905, a mass meeting was h ...

in response to Japanese and other Asian immigration. Anti-Japanese and anti-Chinese riots also frequently broke out. During World War II, Japanese Canadians

are Canadian citizens of Japanese ancestry. Japanese Canadians are mostly concentrated in Western Canada, especially in the province of British Columbia, which hosts the largest Japanese community in the country with the majority of them living ...

were interned

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

like their American counterparts. Financial compensation for surviving internees was finally paid in 1988 by the Brian Mulroney

Martin Brian Mulroney ( ; born March 20, 1939) is a Canadian lawyer, businessman, and politician who served as the 18th prime minister of Canada from 1984 to 1993.

Born in the eastern Quebec city of Baie-Comeau, Mulroney studied political sci ...

government.

China

Anti-Japanese sentiment is felt very strongly in China and distrust, hostility and negative feelings towards Japan and the Japanese people and culture is widespread in China. Anti-Japanese sentiment is a phenomenon that mostly dates back to modern times (since 1868). Like many Western powers during the era of imperialism, Japan negotiated treaties that often resulted in the annexation of land from China towards the end of the

Anti-Japanese sentiment is felt very strongly in China and distrust, hostility and negative feelings towards Japan and the Japanese people and culture is widespread in China. Anti-Japanese sentiment is a phenomenon that mostly dates back to modern times (since 1868). Like many Western powers during the era of imperialism, Japan negotiated treaties that often resulted in the annexation of land from China towards the end of the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

. Dissatisfaction with Japanese settlements and the Twenty-One Demands

The Twenty-One Demands ( ja, 対華21ヶ条要求, Taika Nijūikkajō Yōkyū; ) was a set of demands made during the First World War by the Empire of Japan under Prime Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu to the government of the Republic of China on 18 ...

by the Japanese government led to a serious boycott of Japanese products

Boycotts of Japanese products have been conducted by numerous Korean, Chinese and American

civilian and governmental organizations in response to real or disputed Japanese aggression and atrocities, whether military, political or economic.

20t ...

in China.

Today, bitterness persists in China over the atrocities of the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

and Japan's postwar actions, particularly the perceived lack of a straightforward acknowledgment of such atrocities, the Japanese government's employment of known war criminals, and Japanese historic revisionism in textbooks. In elementary school, children are taught about Japanese war crimes

The Empire of Japan committed war crimes in many Asian-Pacific countries during the period of Japanese militarism, Japanese imperialism, primarily during the Second Sino-Japanese War, Second Sino-Japanese and Pacific Wars. These incidents have b ...

in detail. For example, thousands of children are brought to the Museum of the War of Chinese People's Resistance Against Japanese Aggression

The Museum of the War of Chinese People's Resistance Against Japanese Aggression () or Chinese People's Anti-Japanese War Memorial Hall is a museum and memorial hall in Beijing. It is the most comprehensive museum in China about the Second Sino-Ja ...

in Beijing by their elementary schools and required to view photos of war atrocities, such as exhibits of records of the Japanese military forcing Chinese workers into wartime labor, the Nanking Massacre

The Nanjing Massacre (, ja, 南京大虐殺, Nankin Daigyakusatsu) or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as ''Nanking'') was the mass murder of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the Ba ...

, and the issues of comfort women

Comfort women or comfort girls were women and girls forced into sexual slavery by the Imperial Japanese Army in occupied countries and territories before and during World War II. The term "comfort women" is a translation of the Japanese '' ia ...

. After viewing the museum, the children's hatred of the Japanese people was reported to significantly increase. Despite the time that has passed since the end of the war, discussions about Japanese conduct during it can still evoke powerful emotions today, partly because most Japanese are aware of what happened during it although their society has never engaged in the type of introspection which has been common in Germany after the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

. Hence, the usage of Japanese military symbols are still controversial in China, such as the incident in which the Chinese pop singer Zhao Wei

Zhao Wei (; born 12 March 1976), also known as Vicky Zhao or Vicki Zhao, is a Chinese actress, businesswoman, film director, producer and pop singer. She is considered one of the most popular actresses in China and Chinese-speaking regions, an ...

was seen wearing a Japanese war flag while she was dressed for a fashion magazine photo shoot in 2001. Huge responses were seen on the Internet

The Internet (or internet) is the global system of interconnected computer networks that uses the Internet protocol suite (TCP/IP) to communicate between networks and devices. It is a '' network of networks'' that consists of private, pub ...

, a public letter demanding a public apology was also circulated by a Nanking Massacre survivor, and the singer was even attacked. According to a 2017 BBC World Service

The BBC World Service is an international broadcasting, international broadcaster owned and operated by the BBC, with funding from the Government of the United Kingdom, British Government through the Foreign Secretary, Foreign Secretary's o ...

Poll, only 22% of Chinese people view Japan's influence positively, and 75% express a negative view, making China the most anti-Japanese nation in the world.

In recent times, Chinese Japanophiles are often denounced by nationalists

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

as Hanjian

In Chinese culture, the word ''hanjian'' () is a pejorative term for a traitor to the Han Chinese state and, to a lesser extent, Han ethnicity. The word ''hanjian'' is distinct from the general word for traitor, which could be used for any cou ...

(traitors) or Jingri

The term spiritually Japanese people (; Japanese reading ''Sēshin Nihonjin''), abbreviated as ''jingri'' (), is a pejorative term used in political and social discourse in mainland China referring to people of non-Japanese descent who are perceive ...

.

Anti-Japanese film industry

Anti-Japanese sentiment can also be seen in war films which are currently being produced and broadcast in Mainland China. More than 200 anti-Japanese films were produced in China in 2012 alone. In one particular situation involving a more moderate anti-Japanese war film, the government of China banned the 2000 film, ''Devils on the Doorstep

''Devils on the Doorstep'' (; ja, 鬼が来た!; literally "the devils are here"; the devil is a term of abuse for foreign invaders, here referring to brutal and violent Japanese invaders in China during World War II) is a 2000 Chinese black come ...

'' because it depicted a Japanese soldier being friendly with Chinese villagers.

France

Japan's public service broadcaster,NHK

, also known as NHK, is a Japanese public broadcaster. NHK, which has always been known by this romanized initialism in Japanese, is a statutory corporation funded by viewers' payments of a television license fee.

NHK operates two terrestr ...

, provides a list of overseas safety risks for traveling, and in early 2020, it listed anti-Japanese discrimination as a safety risk on travel to France and some other European countries, possibly because of fears over the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is an ongoing global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The novel virus was first identif ...

and other factors. Signs of rising anti-Japanese sentiment in France include an increase in anti-Japanese incidents reported by Japanese nationals, such as being mocked on the street and refused taxi service, and least one Japanese restaurant has been vandalized. A group of Japanese students on a study tour in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

received abuse by locals. Another group of Japanese citizens was targeted by acid attacks, which prompted the Japanese embassy as well as the foreign ministry to issue a warning to Japanese nationals in France, urging caution. Due to rising discrimination, a Japanese TV announcer in Paris said it's best not to speak Japanese in public or wear a Japanese costume like a kimono. Japanese people are also subject to many stereotypes from the French Entertainment industry that has cemented a general image, often a negative one.

Germany

According to theJapanese foreign ministry

The is an executive department of the Government of Japan, and is responsible for the country's foreign policy and international relations.

The ministry was established by the second term of the third article of the National Government Organi ...

, anti-Japanese sentiment and discrimination has been rising in Germany, especially when the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is an ongoing global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The novel virus was first identif ...

began affecting the country.

Media sources have reported a rise in anti-Japanese sentiment in Germany, with some Japanese residents saying suspicion and contempt towards them have increased noticeably. In line with those sentiments, there have been a rising number of anti-Japanese incidents such as at least one major football club kicking out all Japanese fans from their stadium over fears of the coronavirus, locals throwing raw eggs at Japanese people's homes and a general increase in the level of harassment toward Japanese residents.

Indonesia

In a press release, the embassy of Japan inIndonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

stated that incidents of discrimination and harassment of Japanese people had increased, and they were possibly partly related to the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is an ongoing global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The novel virus was first identif ...

in 2020, and it also announced that it had set up a help center in order to assist Japanese residents in dealing with those incidents. In general, there have been reports of widespread anti-Japanese discrimination and harassment in the country, with hotels, stores, restaurants, taxi services and more refusing Japanese customers and many Japanese people were no longer allowed in meetings and conferences. The embassy of Japan has also received at least a dozen reports of harassment toward Japanese people in just a few days. According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan)

The is an executive department of the Government of Japan, and is responsible for the country's foreign policy and international relations.

The ministry was established by the second term of the third article of the National Government Organ ...

, anti-Japanese sentiment and discrimination has been rising in Indonesia.

Korea

The issue of anti-Japanese sentiment in Korea is complex and multifaceted. Anti-Japanese attitudes in theKorean Peninsula

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

can be traced as far back as the Japanese pirate raids and the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598)

The Japanese invasions of Korea of 1592–1598 involved two separate yet linked invasions: an initial invasion in 1592 (), a brief truce in 1596, and a second invasion in 1597 (). The conflict ended in 1598 with the withdrawal of Japanese force ...

, but they are largely a product of the Japanese occupation of Korea

Between 1910 and 1945, Korea was ruled as a part of the Empire of Japan. Joseon, Joseon Korea had come into the Japanese sphere of influence with the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876; a complex coalition of the Meiji period, Meiji government, military ...

which lasted from 1910 to 1945 and the subsequent revisionism of history textbooks which have been used by Japan's educational system since World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

Today, issues of Japanese history textbook controversies

Japanese history textbook controversies involve controversial content in government-approved history textbooks used in the secondary education (junior high schools and high schools) of Japan. The controversies primarily concern the nationalist ri ...

, Japanese policy regarding the war, and geographic disputes between the two countries perpetuate that sentiment, and the issues often incur huge disputes between Japanese and South Korean Internet users. South Korea, together with Mainland China, may be considered as among the most intensely anti-Japanese societies in the world. Among all the countries that participated in BBC World Service Poll in 2007 and 2009, South Korea and the People's Republic of China were the only ones whose majorities rated Japan negatively.

Today, chinilpa

''Chinilpa'' ( ko, 친일파, lit. "pro-Japan faction") is a derogatory Korean language term that denotes ethnic Koreans who collaborated with Imperial Japan during the protectorate period of the Korean Empire from 1905 and its colonial rule in K ...

is also associated with general anti-Japanese sentiment in South Korea and is often used as a derogatory term for Japanophilic Koreans.

Anti-Japanese sentiment can at times be seen in Korean media. One example is the widely popular web novel, Solo Leveling

''Solo Leveling'', also alternatively translated as ''Only I Level Up'' (), is a South Korean Web novels in South Korea, web novel written by Chugong. It was serialized in Kakao's digital comic and fiction platform KakaoPage beginning on July 2 ...

in which Japanese characters appear as antagonists who have malicious intent, and want to hurt the Korean protagonist. However, the Webtoon

Webtoons (), are a type of digital comic that originated in South Korea usually meant to be read on smartphones.

While webtoons were mostly unknown outside of Korea during their inception, there has been a surge in popularity internationally ...

version significantly edits such depictions of Japanese characters out, though not completely, in order to avoid upsetting non-Korean readers.

Philippines

Anti-Japanese sentiment in the Philippines can be traced back to the Japanese occupation of the country during World War II and its aftermath. An estimated 1 million Filipinos out of a wartime population of 17 million were killed during the war, and many more Filipinos were injured. Nearly every Filipino family was affected by the war on some level. Most notably, in the city of Mapanique, survivors have recounted the Japanese occupation during which Filipino men were massacred and dozens of women were herded in order to be used as

Anti-Japanese sentiment in the Philippines can be traced back to the Japanese occupation of the country during World War II and its aftermath. An estimated 1 million Filipinos out of a wartime population of 17 million were killed during the war, and many more Filipinos were injured. Nearly every Filipino family was affected by the war on some level. Most notably, in the city of Mapanique, survivors have recounted the Japanese occupation during which Filipino men were massacred and dozens of women were herded in order to be used as comfort women

Comfort women or comfort girls were women and girls forced into sexual slavery by the Imperial Japanese Army in occupied countries and territories before and during World War II. The term "comfort women" is a translation of the Japanese '' ia ...

. Today the Philippines has peaceful relations with Japan. In addition, Filipinos are generally not as offended as Chinese or Koreans are by the claim from some quarters that the atrocities are given little, if any, attention in Japanese classrooms. This feeling exists as a result of the huge amount of Japanese aid which was sent to the country during the 1960s and 1970s.

The Davao Region

Davao Region, formerly called Southern Mindanao ( ceb, Rehiyon sa Davao; fil, Rehiyon ng Davao), is an administrative region in the Philippines, designated as Region XI. It is situated at the southeastern portion of Mindanao and comprises fi ...

, in Mindanao

Mindanao ( ) ( Jawi: مينداناو) is the second-largest island in the Philippines, after Luzon, and seventh-most populous island in the world. Located in the southern region of the archipelago, the island is part of an island group of ...

, had a large community of Japanese immigrants which acted as a fifth column by welcoming the Japanese invaders during the war. The Japanese were hated by the Moro Muslims and the Chinese. The Moro juramentados

Juramentado, in Philippine history, refers to a male Moro swordsman (from the Tausug tribe of Sulu) who attacked and killed targeted occupying and invading police and soldiers, expecting to be killed himself, the martyrdom undertaken as a form of ...

s performed suicide attacks against the Japanese, and no Moro juramentado ever attacked the Chinese, who were not considered enemies of the Moro, unlike the Japanese.

According to a 2011 BBC World Service

The BBC World Service is an international broadcasting, international broadcaster owned and operated by the BBC, with funding from the Government of the United Kingdom, British Government through the Foreign Secretary, Foreign Secretary's o ...

Poll, 84% of Filipinos

Filipinos ( tl, Mga Pilipino) are the people who are citizens of or native to the Philippines. The majority of Filipinos today come from various Austronesian ethnolinguistic groups, all typically speaking either Filipino, English and/or othe ...

view Japan's influence positively, with 12% expressing a negative view, making Philippines one of the most pro-Japanese countries in the world.

Singapore

The older generation of Singaporeans have some resentment towards Japan due to their experiences in World War II when Singapore was under Japanese Occupation but because of developing good economical ties with them, Singapore is currently having a positive relationship with Japan.Taiwan

The

The Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

(KMT), which took over Taiwan in the 1940s, held strong anti-Japanese sentiment and sought to eradicate traces of the Japanese culture in Taiwan.

During the 2005 anti-Japanese demonstrations

The anti-Japanese demonstrations of 2005 were a series of demonstrations, some peaceful, some violent, which were held across most of East Asia in the spring of 2005. They were sparked off by a number of issues, including the approval of a Japane ...

in East Asia, Taiwan remained noticeably quieter than the PRC or Korea, with Taiwan-Japan relations regarded at an all-time high. However, the KMT victory in 2008 was followed by a boating accident resulting in Taiwanese deaths, which caused recent tensions. Taiwanese officials began speaking out on the historical territory disputes regarding the Diaoyutai/Senkaku Islands, which resulted in an increase in at least perceived anti-Japanese sentiment.

Thailand

Anti-Japanese sentiment was widespread among Thai pro-democracy student protesters in the 1970s. Demonstrators viewed the entry of Japanese companies into the country, invited by the Thai military, as an economic invasion. Anti-Japanese sentiment in the country has since then simmered down.Russian Empire and Soviet Union

In theRussian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, the Japanese victory during the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

in 1905 halted Russia's ambitions in the East and left it humiliated. During the later Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

, Japan was part of the Allied interventionist forces that helped to occupy Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea ...

until October 1922 with a puppet government

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sovere ...

under Grigorii Semenov. At the end of World War II, the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

accepted the surrender of nearly 600,000 Japanese POWs after Emperor Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

announced the Japanese surrender on 15 August; 473,000 of them were repatriated, 55,000 of them had died in Soviet captivity, and the fate of the others is unknown. Presumably, many of them were deported to China or North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu River, Y ...

and forced to serve as laborers and soldiers. The Kuril Islands dispute

The Kuril Islands dispute, known as the Northern Territories dispute in Japan, is a territorial dispute between Japan and Russia over the ownership of the four southernmost Kuril Islands. The Kuril Islands are a chain of islands that stretch b ...

is a source of contemporary anti-Japanese sentiment in Russia.

United Kingdom

In the 1902, the United Kingdom signed a formal military alliance with Japan. However, the alliance was especially discontinued in 1923, and by the 1930s, bilateral ties became strained when Britain opposed Japan's military expansion. During World War II, British anti-Japanese propaganda, much like its American counterpart, featured content that grotesquely exaggerated physical features of Japanese people, if not outright depicting them as animals such as spiders. Post-war, much anti-Japanese sentiment in Britain was focused on the appalling treatment of BritishPOW

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war ...

s (See ''The Bridge on the River Kwai

''The Bridge on the River Kwai'' is a 1957 epic war film directed by David Lean and based on the 1952 novel written by Pierre Boulle. Although the film uses the historical setting of the construction of the Burma Railway in 1942–1943, the pl ...

'').

United States

Pre-20th century

In theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, anti-Japanese sentiment

Anti-Japanese sentiment (also called Japanophobia, Nipponophobia and anti-Japanism) involves the hatred or fear of anything which is Japanese, be it its culture or its people. Its opposite is Japanophilia.

Overview

Anti-Japanese sentim ...

had its beginnings long before World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. As early as the late 19th century, Asian immigrants were subjected to racial prejudice in the United States. Laws were passed which openly discriminated against Asians and sometimes, they particularly discriminated against Japanese. Many of these laws stated that Asians could not become US citizens and they also stated that Asians could not be granted basic rights such as the right to own land. These laws were greatly detrimental to the newly-arrived immigrants because they denied them the right to own land and forced many of them who were farmers to become migrant workers. Some cite the formation of the Asiatic Exclusion League

The Asiatic Exclusion League (often abbreviated AEL) was an organization formed in the early 20th century in the United States and Canada that aimed to prevent immigration of people of Asian origin.

United States

In May 1905, a mass meeting was h ...

as the start of the anti-Japanese movement in California.

Early 20th century

Anti-Japanese racism and the belief in theYellow Peril

The Yellow Peril (also the Yellow Terror and the Yellow Specter) is a racist, racial color terminology for race, color metaphor that depicts the peoples of East Asia, East and Southeast Asia as an existential danger to the Western world. As a ...

in California intensified after the Japanese victory over the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

during the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

. On 11 October 1906, the San Francisco, California Board of Education passed a regulation in which children of Japanese descent would be required to attend racially-segregated separate schools. Japanese immigrants then made up approximately 1% of the population of California, and many of them had come under the treaty in 1894 which had assured free immigration from Japan.

The Japanese invasion of Manchuria, China, in 1931 and was roundly criticized in the US. In addition, efforts by citizens outraged at Japanese atrocities, such as the Nanking Massacre

The Nanjing Massacre (, ja, 南京大虐殺, Nankin Daigyakusatsu) or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as ''Nanking'') was the mass murder of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the Ba ...

, led to calls for American economic intervention to encourage Japan to leave China. The calls played a role in shaping American foreign policy. As more and more unfavorable reports of Japanese actions came to the attention of the American government, embargoes on oil and other supplies were placed on Japan out of concern for the Chinese people and for the American interests in the Pacific. Furthermore, European-Americans became very pro-China and anti-Japan, an example being a grassroots campaign for women to stop buying silk stockings because the material was procured from Japan through its colonies.

When the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

broke out in 1937, Western public opinion was decidedly pro-China, with eyewitness reports by Western journalists on atrocities committed against Chinese civilians further strengthening anti-Japanese sentiments. African-American sentiments could be quite different than the mainstream and included organizations like the Pacific Movement of the Eastern World

The Pacific Movement of the Eastern World (PMEW) was a 1930s North American based pro-Japanese movement of African Americans which promoted the idea that Japan was the champion of all non-white peoples.

The Japanese ultra-nationalist Black Dragon ...

(PMEW), which promised equality and land distribution under Japanese rule. The PMEW had thousands of members hopefully preparing for liberation from white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White su ...

with the arrival of the Japanese Imperial Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emperor o ...

.

World War II

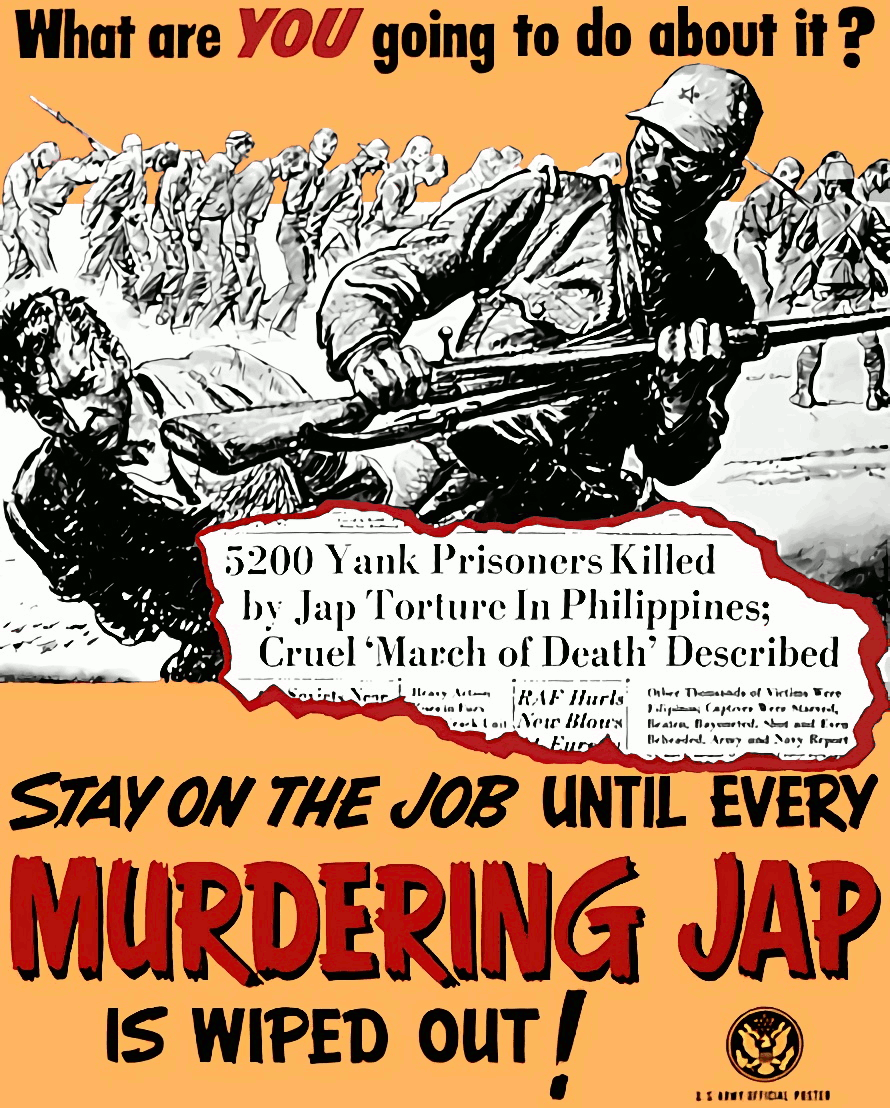

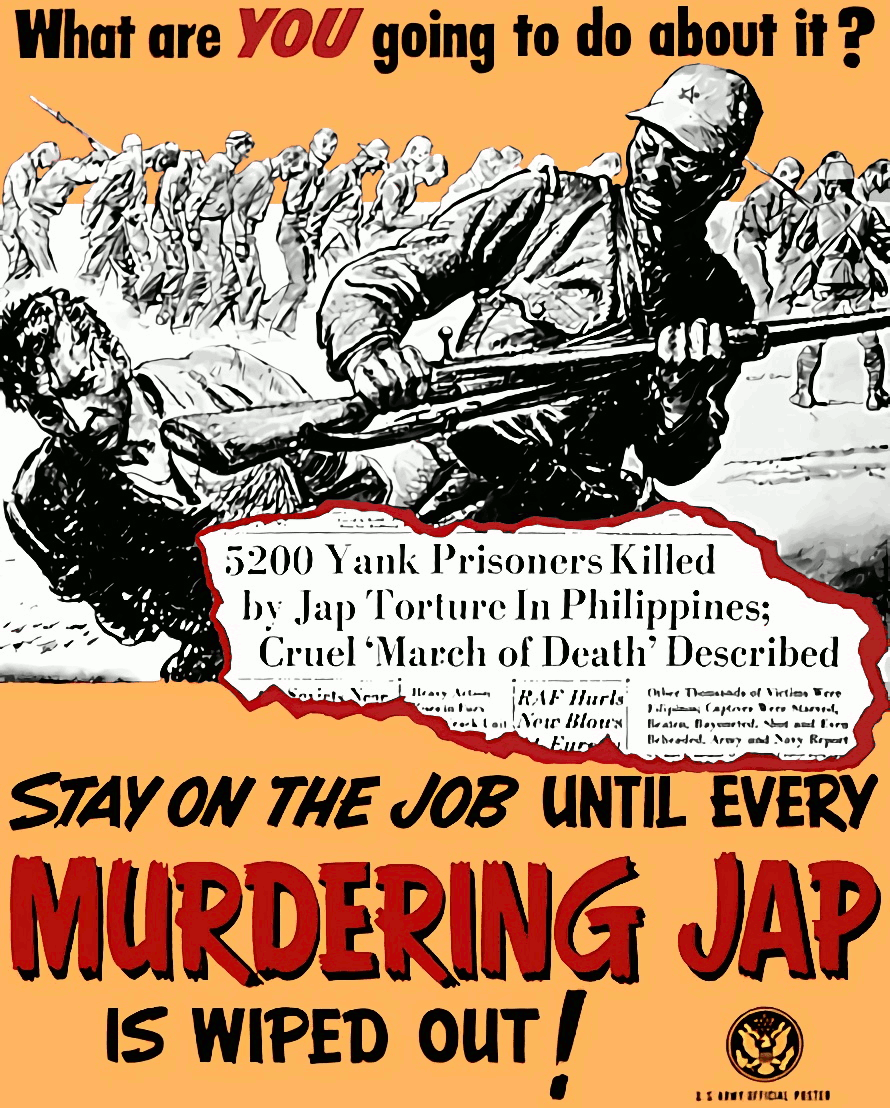

The most profound cause of anti-Japanese sentiment outside of Asia started by the Japanese

The most profound cause of anti-Japanese sentiment outside of Asia started by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, j ...

, which propelled the United States into World War II. The Americans were unified by the attack to fight the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent fo ...

and its allies: the German Reich

German ''Reich'' (lit. German Realm, German Empire, from german: Deutsches Reich, ) was the constitutional name for the German nation state that existed from 1871 to 1945. The ''Reich'' became understood as deriving its authority and sovereignty ...

and the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

.

The surprise attack on Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Re ...

without a declaration of war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state (polity), state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the signing of a document) by an authorized party of a nationa ...

was commonly regarded as an act of treachery and cowardice. After the attack, many non-governmental " Jap hunting licenses" were circulated around the country. ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energ ...

'' magazine published an article on how to tell the difference between Japanese and Chinese by describing the shapes of their noses and the statures of their bodies. Additionally, Japanese conduct during the war did little to quell anti-Japanese sentiment. The flames of outrage were fanned by the treatment of American and other prisoners-of-war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war ...

(POWs). The Japanese military's outrages included the murder of POWs, the use of POWs as slave laborers by Japanese industries, the Bataan Death March

The Bataan Death March (Filipino: ''Martsa ng Kamatayan sa Bataan''; Spanish: ''Marcha de la muerte de Bataán'' ; Kapampangan: ''Martsa ning Kematayan quing Bataan''; Japanese: バターン死の行進, Hepburn: ''Batān Shi no Kōshin'') was ...

, the kamikaze

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending to d ...

attacks on Allied ships, the atrocities which were committed on Wake Island

Wake Island ( mh, Ānen Kio, translation=island of the kio flower; also known as Wake Atoll) is a coral atoll in the western Pacific Ocean in the northeastern area of the Micronesia subregion, east of Guam, west of Honolulu, southeast of To ...

, and other atrocities which were committed elsewhere.

The US historian James J. Weingartner attributes the very low number of Japanese in US POW compounds to two key factors: a Japanese reluctance to surrender and a widespread American "conviction that the Japanese were 'animals' or 'subhuman' and unworthy of the normal treatment accorded to POWs." The latter reasoning is supported by Niall Ferguson

Niall Campbell Ferguson FRSE (; born 18 April 1964)Biography

Niall Ferguson

: "Allied troops often saw the Japanese in the same way that Germans regarded Russians ic— as Niall Ferguson

Untermenschen

''Untermensch'' (, ; plural: ''Untermenschen'') is a Nazi term for non-Aryan "inferior people" who were often referred to as "the masses from the East", that is Jews, Roma, and Slavs (mainly ethnic Poles, Serbs, and later also Russians). The ...

." Weingartner believed that to explain why merely 604 Japanese captives were alive in Allied POW camps by October 1944.

Ulrich Straus, a US Japanologist

Japanese studies (Japanese: ) or Japan studies (sometimes Japanology in Europe), is a sub-field of area studies or East Asian studies involved in social sciences and humanities research on Japan. It incorporates fields such as the study of Japanese ...

, wrote that frontline troops intensely hated Japanese military personnel and were "not easily persuaded" to take or protect prisoners, as they believed that Allied personnel who surrendered got "no mercy" from the Japanese.

Allied soldiers believed that Japanese soldiers were inclined to feign surrender in order to launch surprise attacks. Therefore, according to Straus, " nior officers opposed the taking of prisoners on the grounds that it needlessly exposed American troops to risks...."

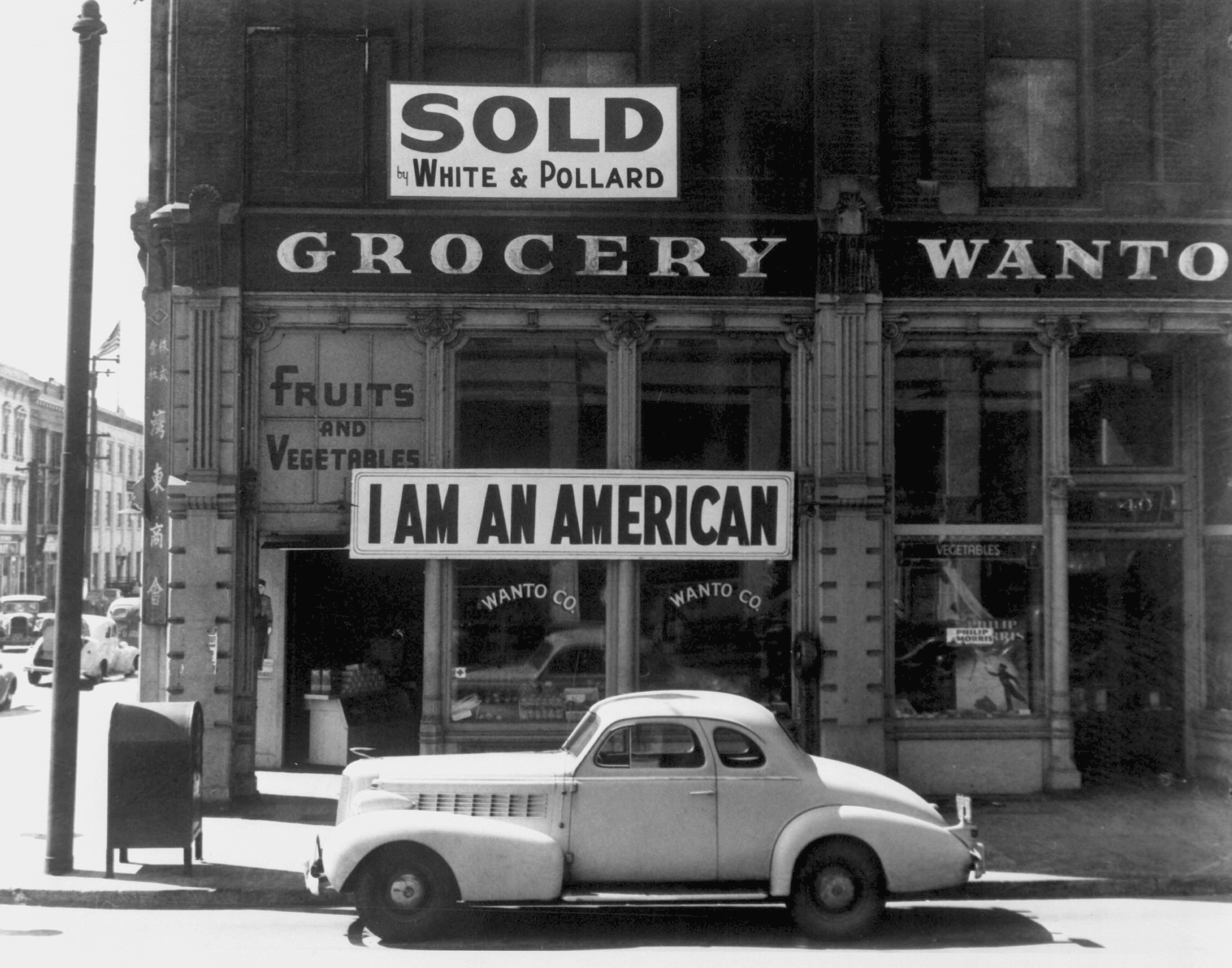

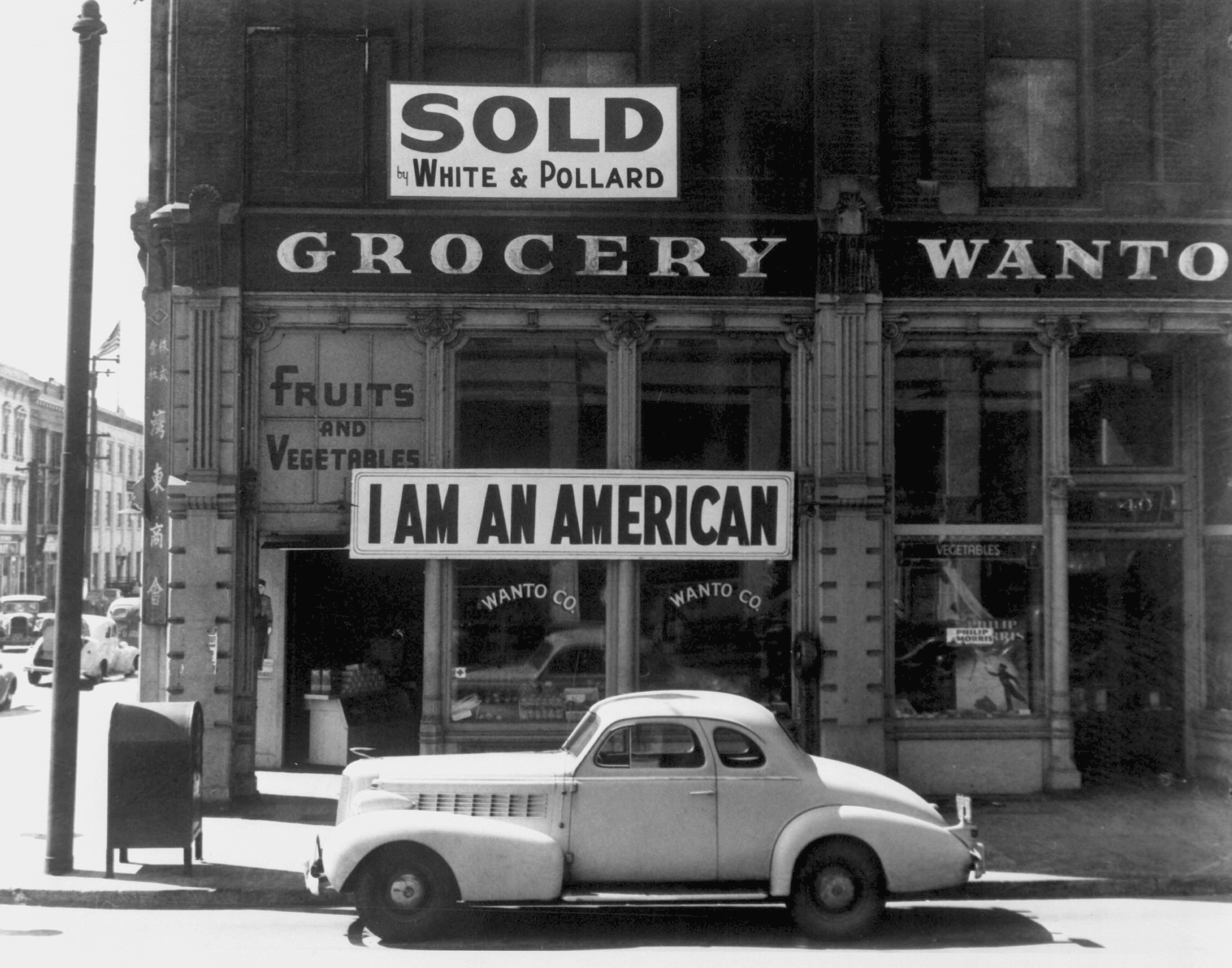

An estimated 112,000 to 120,000 Japanese migrants and

An estimated 112,000 to 120,000 Japanese migrants and Japanese Americans

are Americans of Japanese ancestry. Japanese Americans were among the three largest Asian American ethnic communities during the 20th century; but, according to the 2000 census, they have declined in number to constitute the sixth largest Asi ...

from the West Coast were interned regardless of their attitude to the US or to Japan. They were held for the duration of the war in the Continental US

The contiguous United States (officially the conterminous United States) consists of the 48 adjoining U.S. states and the Federal District of the United States of America. The term excludes the only two non-contiguous states, Alaska and Hawaii ...

. Only a few members of the large Japanese population of Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

were relocated in spite of the proximity to vital military areas.

A 1944 opinion poll

An opinion poll, often simply referred to as a survey or a poll (although strictly a poll is an actual election) is a human research survey of public opinion from a particular sample. Opinion polls are usually designed to represent the opinions ...

found that 13% of the US public supported the genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Latin ...

of all Japanese. Daniel Goldhagen

Daniel Jonah Goldhagen (born June 30, 1959) is an American author, and former associate professor of government and social studies at Harvard University. Goldhagen reached international attention and broad criticism as the author of two controve ...

wrote in his book, "So it is no surprise that Americans perpetrated and supported mass slaughters - Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.468 ...

's firebombing and then nuclear incinerations - in the name of saving American lives, and of giving the Japanese what they richly deserved."

=Decision to drop the atomic bombs

= Weingartner argued that there was a common cause between the mutilation of Japanese war dead and the decision to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki. According to Weingartner, both of these decisions were partially the result of the dehumanization of the enemy: "The widespread image of the Japanese as sub-human constituted an emotional context which provided another justification for decisions which resulted in the death of hundreds of thousands." Two days after the Nagasaki bomb, US PresidentHarry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

stated: "The only language they seem to understand is the one we have been using to bombard them. When you have to deal with a beast you have to treat him like a beast. It is most regrettable but nevertheless true."

Postwar

In the 1970s and the 1980s, the waning fortunes of heavy industry in the United States prompted layoffs and hiring slowdowns just as counterpart businesses in Japan were making major inroads into US markets. That was most visible than in the automobile industry whose lethargic Big Three (General Motors

The General Motors Company (GM) is an American Multinational corporation, multinational Automotive industry, automotive manufacturing company headquartered in Detroit, Michigan, United States. It is the largest automaker in the United States and ...

, Ford

Ford commonly refers to:

* Ford Motor Company, an automobile manufacturer founded by Henry Ford

* Ford (crossing), a shallow crossing on a river

Ford may also refer to:

Ford Motor Company

* Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company

* Ford F ...

, and Chrysler

Stellantis North America (officially FCA US and formerly Chrysler ()) is one of the " Big Three" automobile manufacturers in the United States, headquartered in Auburn Hills, Michigan. It is the American subsidiary of the multinational automoti ...

) watched as their former customers bought Japanese imports from Honda

is a Japanese public multinational conglomerate manufacturer of automobiles, motorcycles, and power equipment, headquartered in Minato, Tokyo, Japan.

Honda has been the world's largest motorcycle manufacturer since 1959, reaching a product ...

, Subaru

( or ; ) is the automaker, automobile manufacturing division of Japanese transportation conglomerate (company), conglomerate Subaru Corporation (formerly known as Fuji Heavy Industries), the Automotive industry#By manufacturer, twenty-first ...

, Mazda

, commonly referred to as simply Mazda, is a Japanese multinational automotive manufacturer headquartered in Fuchū, Hiroshima, Japan.

In 2015, Mazda produced 1.5 million vehicles for global sales, the majority of which (nearly one m ...

, and Nissan

, trade name, trading as Nissan Motor Corporation and often shortened to Nissan, is a Japanese multinational corporation, multinational Automotive industry, automobile manufacturer headquartered in Nishi-ku, Yokohama, Japan. The company sells ...

because of the 1973 oil crisis

The 1973 oil crisis or first oil crisis began in October 1973 when the members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), led by Saudi Arabia, proclaimed an oil embargo. The embargo was targeted at nations that had supp ...

and the 1979 energy crisis

The 1979 oil crisis, also known as the 1979 Oil Shock or Second Oil Crisis, was an energy crisis caused by a drop in oil production in the wake of the Iranian Revolution. Although the global oil supply only decreased by approximately four per ...

. (When Japanese automakers were establishing their inroads into the US and Canada. Isuzu, Mazda, and Mitsubishi had joint partnerships with a Big Three manufacturer (GM, Ford, and Chrysler) in which its products were sold as captives

''Captives'' is a 1994 British romantic crime drama film directed by Angela Pope and written by the Dublin screenwriter Frank Deasy. It stars Julia Ormond, Tim Roth and Keith Allen (actor), Keith Allen. The picture was selected as the opening fil ...

). Anti-Japanese sentiment was reflected in opinion polling at the time as well as in media portrayals. Extreme manifestations of anti-Japanese sentiment were occasional public destruction of Japanese cars and in the 1982 murder of Vincent Chin

Vincent Jen Chin ( zh, first=t, t=陳果仁; May 18, 1955 – June 23, 1982) was an American draftsman of Chinese descent who was killed in a racially motivated assault by two white men, Chrysler plant supervisor Ronald Ebens and his stepson, ...

, a Chinese-American

Chinese Americans are Americans of Han Chinese ancestry. Chinese Americans constitute a subgroup of East Asian Americans which also constitute a subgroup of Asian Americans. Many Chinese Americans along with their ancestors trace lineage from m ...

who was beaten to death after he had been mistaken for being Japanese.

Anti-Japanese sentiments were intentionally incited by US politicians as part of partisan politics designed to attack the Reagan presidency.

Other highly-symbolic deals, including the sale of famous American commercial and cultural symbols such as Columbia Records

Columbia Records is an American record label owned by Sony Music, Sony Music Entertainment, a subsidiary of Sony Corporation of America, the North American division of Japanese Conglomerate (company), conglomerate Sony. It was founded on Janua ...

, Columbia Pictures

Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. is an American film production studio that is a member of the Sony Pictures Motion Picture Group, a division of Sony Pictures Entertainment, which is one of the Big Five studios and a subsidiary of the mu ...

, 7-Eleven

7-Eleven, Inc., stylized as 7-ELEVE, is a multinational chain of retail convenience stores, headquartered in Dallas, Texas. The chain was founded in 1927 as an ice house storefront in Dallas. It was named Tote'm Stores between 1928 and 1946. A ...

, and the Rockefeller Center

Rockefeller Center is a large complex consisting of 19 commerce, commercial buildings covering between 48th Street (Manhattan), 48th Street and 51st Street (Manhattan), 51st Street in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. The 14 original Art Deco ...

building to Japanese firms, further fanned anti-Japanese sentiment.

Popular culture

Popular culture (also called mass culture or pop culture) is generally recognized by members of a society as a set of practices, beliefs, artistic output (also known as, popular art or mass art) and objects that are dominant or prevalent in a ...

of the period reflected American's growing distrust of Japan. Futuristic period pieces such as ''Back to the Future Part II

''Back to the Future Part II'' is a 1989 American science fiction film directed by Robert Zemeckis from a screenplay by Bob Gale and a story by both. It is the sequel to the 1985 film ''Back to the Future'' and the second installment in the ' ...

'' and ''RoboCop 3

''RoboCop 3'' is a 1993 American science fiction action film directed by Fred Dekker and written by Dekker and Frank Miller. It is the sequel to the 1990 film ''RoboCop 2'' and the third entry in the ''RoboCop'' franchise. It stars Robert Bur ...

'' frequently showed Americans as working precariously under Japanese superiors. The film ''Blade Runner

''Blade Runner'' is a 1982 science fiction film directed by Ridley Scott, and written by Hampton Fancher and David Peoples. Starring Harrison Ford, Rutger Hauer, Sean Young, and Edward James Olmos, it is an adaptation of Philip K. Dick' ...

'' showed a futuristic Los Angeles clearly under Japanese domination, with a Japanese majority population and culture, perhaps a reference to the alternate world presented in the novel ''The Man in the High Castle

''The Man in the High Castle'' (1962), by Philip K. Dick, is an alternative history novel wherein the Axis Powers won World War II. The story occurs in 1962, fifteen years after the end of the war in 1947, and depicts the political intrigues be ...

'' by Philip K. Dick, the same author on which the film was based in which Japan had won World War II. Criticism was also lobbied in many novels of the day. The author Michael Crichton

John Michael Crichton (; October 23, 1942 – November 4, 2008) was an American author and filmmaker. His books have sold over 200 million copies worldwide, and over a dozen have been adapted into films. His literary works heavily feature tech ...

wrote '' Rising Sun'', a murder mystery

Crime fiction, detective story, murder mystery, mystery novel, and police novel are terms used to describe narratives that centre on criminal acts and especially on the investigation, either by an amateur or a professional detective, of a crime, ...

(later made into a feature film

A feature film or feature-length film is a narrative film (motion picture or "movie") with a running time long enough to be considered the principal or sole presentation in a commercial entertainment program. The term ''feature film'' originall ...

) involving Japanese businessmen in the US. Likewise, in Tom Clancy

Thomas Leo Clancy Jr. (April 12, 1947 – October 1, 2013) was an American novelist. He is best known for his technically detailed espionage and military science, military-science storylines set during and after the Cold War. Seventeen of ...

's book, ''Debt of Honor