Anti-Arabism In Europe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anti-Arabism, Anti-Arab sentiment, or Arabophobia includes opposition to, dislike, fear, or hatred of

Anti-Arab prejudice is suggested by many events in history. In the

Anti-Arab prejudice is suggested by many events in history. In the

The

The

In 2004, then Deputy Defense Minister

In 2004, then Deputy Defense Minister

An October 2001 report on civil liberties in the U.S. including an appendix of some anti-Arab hate-based incidents

Aljazeera.com: What do Israelis say about the Arabs

ADL statement against Anti-Arab prejudice

{{Discrimination Anti-Arabism, Politics and race Orientalism Racism

Arab people

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Wester ...

.

Historically, anti-Arab prejudice has been an issue in such events as the reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

, the condemnation of Arabs in Spain by the Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition ( es, Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición), commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition ( es, Inquisición española), was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand ...

, the Zanzibar Revolution

The Zanzibar Revolution () occurred in January 1964 and led to the overthrow of the Sultan of Zanzibar and his mainly Arab government by local Africans.

Zanzibar was an ethnically diverse state consisting of a number of islands off the east co ...

in 1964, and the 2005 Cronulla riots

The 2005 Cronulla riots were a race riot in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. It began in the beachside suburb of Cronulla on 11 December, and spread over to additional suburbs the next few nights.

The riots were triggered by an event the pr ...

in Australia. In the modern era, anti-Arabism is apparent in many nations in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

and the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

. Various advocacy organizations have been formed to protect the civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

of individuals of Arab descent in the United States, such as the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee

The American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC) states that it is "the largest Arab American grassroots civil rights organization in the United States." According to its webpage it is open to people of all backgrounds, faiths and ethnicities ...

(ADC) and the Council on American-Islamic Relations

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or natio ...

(CAIR).

Definition of Arab

Arabs are people whose native language is Arabic. People ofArab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

ic origin, in particular native English and French speakers of Arab ancestry in Europe and the Americas, often identify themselves as Arabs. Due to widespread practice of Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

among Arab populations, Anti-Arabism is commonly confused with Islamophobia

Islamophobia is the fear of, hatred of, or prejudice against the religion of Islam or Muslims in general, especially when seen as a geopolitical force or a source of terrorism.

The scope and precise definition of the term ''Islamophobia'' ...

.

There are prominent Arab non-Muslim minorities in the Arab world. These minorities include the Arab Christians

Arab Christians ( ar, ﺍَﻟْﻤَﺴِﻴﺤِﻴُّﻮﻥ ﺍﻟْﻌَﺮَﺏ, translit=al-Masīḥīyyūn al-ʿArab) are ethnic Arabs, Arab nationals, or Arabic-speakers who adhere to Christianity. The number of Arab Christians who l ...

in Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

, Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

, Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, Kuwait

Kuwait (; ar, الكويت ', or ), officially the State of Kuwait ( ar, دولة الكويت '), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated in the northern edge of Eastern Arabia at the tip of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to the nort ...

and Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and an ...

, among other Arab countries.*

* There are also sizable minorities of Arab Jews

Arab Jews ( ar, اليهود العرب '; he, יהודים ערבים ') is a term for Jews living in or originating from the Arab world. The term is politically contested, often by Zionists or by Jews with roots in the Arab world who prefer ...

, Druze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings of ...

, Baháʼí, and nonreligious

Irreligion or nonreligion is the absence or rejection of religion, or indifference to it. Irreligion takes many forms, ranging from the casual and unaware to full-fledged philosophies such as atheism and agnosticism, secular humanism and a ...

.

Historical anti-Arabism

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

, when the reconquest by the indigenous Christians from the Moorish colonists was completed with the fall of Granada

Granada (,, DIN 31635, DIN: ; grc, Ἐλιβύργη, Elibýrgē; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the fo ...

, all non-Catholics were expelled. In 1492, Arab converts to Christianity, called Morisco

Moriscos (, ; pt, mouriscos ; Spanish for "Moorish") were former Muslims and their descendants whom the Roman Catholic church and the Spanish Crown commanded to convert to Christianity or face compulsory exile after Spain outlawed the open p ...

s, were expelled from Spain to North Africa after being condemned by the Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition ( es, Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición), commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition ( es, Inquisición española), was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand ...

. The Spanish word "moro", meaning ''moor'', today carries a negative meaning.

After the annexation

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

of the Muslim-ruled state of Hyderabad

Hyderabad ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Telangana and the ''de jure'' capital of Andhra Pradesh. It occupies on the Deccan Plateau along the banks of the Musi River (India), Musi River, in the northern part ...

by India in 1948, about 7,000 Arabs were interned and deported.

The Zanzibar Revolution

The Zanzibar Revolution () occurred in January 1964 and led to the overthrow of the Sultan of Zanzibar and his mainly Arab government by local Africans.

Zanzibar was an ethnically diverse state consisting of a number of islands off the east co ...

of January 12, 1964, ended the local Arab dynasty. As many as 17,000 Arabs were exterminated by black African

Black is a Racialization, racialized classification of people, usually a Politics, political and Human skin color, skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have ...

revolutionaries, according to reports, and thousands of others fled the country.

In ''The Arabic Language and National Identity: a Study in Ideology'', Yasir Suleiman

Yasir Suleiman CBE is the Sultan Qaboos Bin Said Professor of Modern Arabic Studies at the University of Cambridge. He is a Palestinian Arab living in the diaspora.

Suleiman holds degrees from Amman University, the University of St Andrews, and ...

notes of the writing of Tawfiq al-Fikayki that he uses the term ''shu'ubiyya'' to refer to movements he perceives to be anti-Arab, such as the Turkification

Turkification, Turkization, or Turkicization ( tr, Türkleştirme) describes a shift whereby populations or places received or adopted Turkic attributes such as culture, language, history, or ethnicity. However, often this term is more narrowly ...

movement in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, extreme-nationalist and Pan-Iranist

Pan-Iranism is an ideology that advocates solidarity and reunification of Iranian peoples living in the Iranian plateau and other regions that have significant Iranian cultural influence, including the Persians, Azerbaijanis (a Turkic-speakin ...

movements in Iran and communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

. The economic boom in Iran which lasted until 1979 led to an overall increase of Iranian nationalism sparking thousands of anti-Arab movements. In al-Fikayki's view, the objectives of anti-Arabism are to attack Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism ( ar, القومية العربية, al-Qawmīya al-ʿArabīya) is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people, celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language an ...

, pervert history, emphasize Arab regression, deny Arab culture

Arab culture is the culture of the Arabs, from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Arabian Sea in the east, and from the Mediterranean Sea in the north to the Horn of Africa and the Indian Ocean in the southeast. The various religions the Arab ...

, and generally be hostile to all things Arab. He concludes that, "In all its various roles, anti-Arabism has adopted a policy of intellectual conquest as a means of penetrating Arab society and combatting Arab nationalism."

In early 20th and late 19th century when Palestinians and Syrians migrated to Latin America Arabophobia was common in these countries.La "Turcofobia". Discriminación anti-Árabe en Chile.

Modern anti-Arabism

Algeria

Anti-Arabism is a major element of movements known asBerberism

Berberism or Amazighism is a Berber political-cultural movement of ethnic, geographic, or cultural nationalism, started mainly in Kabylia (Algeria) and in Morocco, later spreading to the rest of the Berber communities in the Maghreb region of ...

that are widespread mainly amongst Algerians of Kabyle and other Berber origin. It has historic roots as Arabs are seen as invaders that occupied Algeria and destroyed its late Roman and early medieval civilization that was considered an integral part of the West; this invasion is considered to have been the source of the resettlement of Algeria's Berber population in Kabylie

Kabylia ('' Kabyle: Tamurt n Leqbayel'' or ''Iqbayliyen'', meaning "Land of Kabyles", '','' meaning "Land of the Tribes") is a cultural, natural and historical region in northern Algeria and the homeland of the Kabyle people. It is part of the ...

and other mountainous areas. Regardless, the Kabyles and other Berbers have managed to preserve their culture and achieve higher standards of living and education when compared to Algerian Arabs. Furthermore, many Berbers speak their language and French; are non religious, secular, or Evangelical Christian; and openly identify with the Western World. Many Berber Nationalists view Arabs as a hostile people intent on eradicating their own culture and nation. Berber social norms restrict marriage to someone of Arab ethnicity, although it is permitted to marry someone from other ethnic groups.

According to Lawrence Rosen, ethnic background is not a crucial factor in marriage between members of each group in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, when compared to social and economic backgrounds. There are regular Hate incidents between Arabs and Berbers and Anti-Arabism has been accentuated by the Algerian government's anti-Berber policies. Contemporary relations between Berbers

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, pop2 ...

and Arabs are sometimes tense, particularly in Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

, where Berbers rebelled (1963–65, 2001) against Arab rule and have demonstrated and rioted against their cultural marginalization in the new founded state.

The Anti-Arab sentiments among Algerian Berbers (mainly from Kabylie) were always related to the reassertion of Kabyle identity. It began as an intellectual militant movement in schools, universities, and popular culture (mainly nationalistic songs). In addition to that, the authorities' efforts to promote development in Kabylie contributed to a boom of sorts in Tizi Ouzou

Tizi Ouzou or Thizi Wezzu (, Kabyle: Tizi Wezzu) is a city in north central Algeria. It is among the largest cities in Algeria. It is the second most populous city in the Kabylie region after Bejaia.

History

Etymology

The name ''Tizi Ouzou' ...

, whose population almost doubled between 1966 and 1977, and to a greater degree of economic and social integration within the region had the contrary effect of strengthening a collective Amazigh

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, pop2 ...

consciousness and Anti-Arab sentiments.

Arabophobia can be seen at different levels of intellectual, social, and cultural life of some Berbers. After the Berberist crisis in 1949, a new radical intellectual movement emerged under the name ''L'Académie Berbère''. This movement was known by its adoption and promotion of Anti-Arab and Anti-Islam ideologies especially amongst immigrant Kabyles in France and achieved a relative success at the time.

In 1977, the final game of the national soccer championship pitting a team from Kabylie against one from Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

turned into an Arab-Berber conflict. The Arab national anthem of Algeria was overwhelmed by the shouting of Anti-Arab slogans such as "A bas les arabes" (''down with the Arabs'').

The roots of modern day Arabophobia in Algeria can be traced back to multiple factors. For some, Anti-Arabism movement among Berbers is part of the legacy of French Colonization

The French colonial empire () comprised the overseas colonies, protectorates and mandate territories that came under French rule from the 16th century onward. A distinction is generally made between the "First French Colonial Empire", that exist ...

or manipulation of North Africa. As from the beginning, the French understood that to attenuate Muslim resistance to their presence, mainly in Algeria, they had to resort to the divide and rule

Divide and rule policy ( la, divide et impera), or divide and conquer, in politics and sociology is gaining and maintaining power divisively. Historically, this strategy was used in many different ways by empires seeking to expand their terr ...

doctrine. The most obvious divide that could be instrumentalized in this perspective was the ethnic one. Therefore, France employed some official colonial practices to tighten its control over Algeria by creating racial tensions between Arabs and Berbers and between Jews and Muslims.

Others argue that the Berber language and traditions are deeply rooted in the North African cultural mosaic; for centuries, Berber culture has survived conquests, repression, and exclusion from different invaders: Romans, Arabs, and French. Hence, believing that its identity and specificity were threatened, the Berbers took note of the political and ideological implications of Arabism as defended by successive governments. Gradual radicalization and Anti-Arab sentiments began to emerge in Algeria and among the hundreds of thousands of Berbers in France who had been in the forefront of the Berber cultural movement.

Australia

The

The Cronulla riots

The 2005 Cronulla riots were a race riot in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. It began in the beachside suburb of Cronulla on 11 December, and spread over to additional suburbs the next few nights.

The riots were triggered by an event the pr ...

in Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

, Australia in December 2005 have been described as "anti-Arab racism" by community leaders. NSW Premier Morris Iemma

Morris Iemma (; born 21 July 1961) is a former Australian politician who was the 40th Premier of New South Wales. He served from 3 August 2005 to 5 September 2008. From Sydney, Iemma attended the University of Sydney and the University of Techno ...

said the violence revealed the "ugly face of racism in this country".

A 2004 report by the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission

The Australian Human Rights Commission is the national human rights institution of Australia, established in 1986 as the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) and renamed in 2008. It is a statutory body funded by, but opera ...

said that more than two-thirds of Muslim and Arab Australians say they have experienced racism or racial vilification

A race is a categorization of humans based on shared physical or social qualities into groups generally viewed as distinct within a given society. The term came into common usage during the 1500s, when it was used to refer to groups of variou ...

since the September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commercia ...

and that 90% of female respondents experienced racial abuse or violence.

Adam Houda, a Lebanese Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

lawyer

A lawyer is a person who practices law. The role of a lawyer varies greatly across different legal jurisdictions. A lawyer can be classified as an advocate, attorney, barrister, canon lawyer, civil law notary, counsel, counselor, solic ...

, has been repeatedly harassed by the New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

police force. Houda has been arrested or detained six times in 11 years and has sued the police force for malicious prosecution

Malicious prosecution is a common law intentional tort. Like the tort of abuse of process, its elements include (1) intentionally (and maliciously) instituting and pursuing (or causing to be instituted or pursued) a legal action (civil or criminal ...

and harassment three times. Houda claims that the police's motivation is racism which he says is "alive and well" in Bankstown

Bankstown is a suburb south west of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. It is 16 kilometres south-west of the Sydney central business district and is located in the local government area of the City of Canterbury-Bankstown, hav ...

. He has been stopped going to prayers, with relatives and friends and has been subjected to a humiliating body search. He has been the object of several groundless accusations of robbery or holding a knife. A senior lawyer told the Sydney Morning Herald

''The Sydney Morning Herald'' (''SMH'') is a daily compact newspaper published in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, and owned by Nine. Founded in 1831 as the ''Sydney Herald'', the ''Herald'' is the oldest continuously published newspaper i ...

that the police harassment was due to the police enmity against Houda's clients and the Australian Arab community. He was first falsely arrested in 2000 for which he was awarded $145,000 damages by a judge who described his persecution as "shocking". Constable Lance Stebbing was found to have maliciously arrested Houda, as well as using profanities against him and approaching him in a "menacing manner". Stebbing was supported by other police, against the testimony of many eyewitnesses. In 2005, Houda accused the police of disabling his mobile phone making it difficult to perform his work as a criminal defense lawyer.

In 2010, Houda, his lawyer Chris Murphy, and Channel Seven journalist Adam Walters claimed that Frank Menilli, a senior New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

police officer, behaved in a corrupt fashion by trying to alter Channel Seven's coverage of the Houda Case by promising Walters inside information in exchange for presenting the case in the police's favour. Walters regarded the offer as an "attempted bribe". The latest incident occurred in 2011, when Houda was arrested for refusing a frisk search and resisting arrest after having been approached by police suspecting him of involvement in a recent robbery. These charges were thrown out of court by Judge John Connell who stated "At the end of the day, here were three men of Middle Eastern appearance walking along a suburban street, for all the police knew, minding their own business at an unexceptional time of day, in unexceptional clothing, except two of the men had hooded jumpers. The place they were in could not have raised a reasonable suspicion they were involved in the robberies" Houda is currently suing the six police officers involved for false imprisonment, unlawful arrest, assault and battery and defamation. One of the six is an assistant commissioner. He is seeking $5 million in damages.

Czech Republic

In September 2008, Muslims complained about anti-Arabism and Islamophobia in the Czech Republic. Czech Republic was well known for being the most anti-Arabism country in the whole of Europe in 2008.France

France used to be a colonialempire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

, with still great post-colonial power over its former colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

, using Africa as a reservoir for labor, especially in moments of dire need. During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, reconstruction and shortages made France bring thousands of North African workers. Out of a total of 116,000 workers from 1914–1918, 78,000 Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

ns, 54,000 Moroccans

Moroccans (, ) are the citizens and nationals of the Kingdom of Morocco. The country's population is predominantly composed of Arabs and Berbers (Amazigh). The term also applies more broadly to any people who are of Moroccan nationality, s ...

, and Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

ns were requisitioned. Two hundred and forty thousand Algerians were mobilized or drafted, and two thirds of these were soldiers who served mostly in France. This constituted more than one-third of the men of those nations from ages 20–40. According to historian Abdallah Laroui, Algeria sent 173,000 soldiers, 25,000 of whom were killed. Tunisia sent 56,000, of whom 12,000 were killed. Moroccan soldiers helped defend Paris and landed at Bordeaux in 1916.

After the war, reconstruction and labor shortages necessitated even larger number of Algerian laborers. Migration (or the need for labor) was reestablished at a high level by 1936. This was partly the result of collective recruitments in the villages conducted by French officers and representatives of companies. Labor recruitment continued throughout the 1940s. North Africans were mostly recruited for dangerous and low-wage jobs, unwanted by ordinary French workers.

This large number of immigrants was of great help for France's rapid post–World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

economic growth. The 1970s were marked by recession followed by the cessation of labor migration programs and crackdowns on illegal immigration

Illegal immigration is the migration of people into a country in violation of the immigration laws of that country or the continued residence without the legal right to live in that country. Illegal immigration tends to be financially upwar ...

. During the 1980s, political disfavor with President Mitterrand's social programs led to the rise of Jean-Marie Le Pen

Jean Louis Marie Le Pen (, born 20 June 1928) is a French far-right politician who served as President of the National Front from 1972 to 2011. He also served as Honorary President of the National Front from 2011 to 2015.

Le Pen graduated fro ...

and other far right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

French nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

s. The public increasingly blamed immigrants for French economic problems. In March 1990, according to a poll reported in Le Monde

''Le Monde'' (; ) is a French daily afternoon newspaper. It is the main publication of Le Monde Group and reported an average circulation of 323,039 copies per issue in 2009, about 40,000 of which were sold abroad. It has had its own website si ...

, 76% of those polled said that there were too many Arabs in France while 39% said they had an "aversion" to Arabs. In the following years, Interior Minister Charles Pasqua

Charles Victor Pasqua (18 April 192729 June 2015) was a French businessman and Gaullist politician. He was Interior Minister from 1986 to 1988, under Jacques Chirac's ''cohabitation'' government, and also from 1993 to 1995, under the government o ...

was noted for dramatically toughening immigration laws.

In May 2005, riots broke out between North Africans and Romani people

The Romani (also spelled Romany or Rromani , ), colloquially known as the Roma, are an Indo-Aryan ethnic group, traditionally nomadic itinerants. They live in Europe and Anatolia, and have diaspora populations located worldwide, with sig ...

in Perpignan

Perpignan (, , ; ca, Perpinyà ; es, Perpiñán ; it, Perpignano ) is the prefecture of the Pyrénées-Orientales department in southern France, in the heart of the plain of Roussillon, at the foot of the Pyrenees a few kilometres from the ...

, after a young Arab man was shot dead and another Arab man was lynched by a group of Roma.

Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, , ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. Chirac was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and from 1986 to 1988, as well as Ma ...

's controversial "Hijab ban" law, presented as secularization

In sociology, secularization (or secularisation) is the transformation of a society from close identification with religious values and institutions toward non-religious values and secular institutions. The ''secularization thesis'' expresses the ...

of schools, was interpreted by its critics as an "indirect legitimization of anti-Arab stereotypes, fostering rather than preventing racism."

A higher rate of racial profiling is conducted on Blacks and Arabs by the French police.

Iran

Human rights

Human rights are Morality, moral principles or Social norm, normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for ce ...

group Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says it has more than ten million members and sup ...

says that in practice, Arabs are among a number of ethnic minorities that are disadvantaged and suffer discrimination by the authorities. Separatist

Separatism is the advocacy of cultural, ethnic, tribal, religious, racial, governmental or gender separation from the larger group. As with secession, separatism conventionally refers to full political separation. Groups simply seeking greate ...

tendencies in Khuzestan

Khuzestan Province (also spelled Xuzestan; fa, استان خوزستان ''Ostān-e Xūzestān'') is one of the 31 provinces of Iran. It is in the southwest of the country, bordering Iraq and the Persian Gulf. Its capital is Ahvaz and it covers ...

exacerbate this. How far the situation facing Arabs in Iran is related to racism or simply a result of policies suffered by all Iranians is a matter of debate (''see: Politics of Khuzestan

Khuzestan Province is a petroleum-rich, ethnically-diverse province in southwestern Iran. Oil fields in the province include Ahvaz Field, Marun, Aghajari, Karanj, Shadegan and Mansouri. Amnesty International has voiced human-rights concerns ab ...

''). Iran is a multi-ethnic society with its Arab minority mainly located in the south.

It is claimed by some that anti-Arabism in Iran may be related to the notion that Arabs forced some Persians

The Persians are an Iranian ethnic group who comprise over half of the population of Iran. They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language as well as of the languages that are closely related to Persian.

...

to convert to Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

in 7th century AD (''See: Muslim conquest of Persia

The Muslim conquest of Persia, also known as the Arab conquest of Iran, was carried out by the Rashidun Caliphate from 633 to 654 AD and led to the fall of the Sasanian Empire as well as the eventual decline of the Zoroastrian religion.

Th ...

''). Author Richard Foltz

Richard Foltz is a Canadian scholar of American origin. He is a specialist in the history of Iranian civilization—what is sometimes referred to as "Greater Iran". He has also been active in the areas of environmental ethics and animal rights.

...

in his article "Internationalization of Islam" states "Even today, many Iranians perceive the Arab destruction of the Sassanid Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

as the single greatest tragedy in Iran's long history. Following the Muslim conquest of Persia

The Muslim conquest of Persia, also known as the Arab conquest of Iran, was carried out by the Rashidun Caliphate from 633 to 654 AD and led to the fall of the Sasanian Empire as well as the eventual decline of the Zoroastrian religion.

Th ...

, many Iranians (also known as "mawali

Mawlā ( ar, مَوْلَى, plural ''mawālī'' ()), is a polysemous Arabic word, whose meaning varied in different periods and contexts.A.J. Wensinck, Encyclopedia of Islam 2nd ed, Brill. "Mawlā", vol. 6, p. 874.

Before the Islamic prophet ...

") came to despise the Umayyads Umayyads may refer to:

*Umayyad dynasty, a Muslim ruling family of the Caliphate (661–750) and in Spain (756–1031)

*Umayyad Caliphate (661–750)

:*Emirate of Córdoba (756–929)

:*Caliphate of Córdoba

The Caliphate of Córdoba ( ar, خ ...

due to discrimination against them by their Arab rulers. The Shu'ubiyah movement was intended to reassert Iranian identity and resist attempts to impose Arab culture while reaffirming their commitment to Islam.

More recently, anti-Arabism has arisen as a consequence of aggression against Iran by the regime of Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein ( ; ar, صدام حسين, Ṣaddām Ḥusayn; 28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 16 July 1979 until 9 April 2003. A leading member of the revolution ...

in Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

. During a visit to Khuzestan, which has most of Iran's Arab population, a British journalist, John R. Bradley, wrote that despite the fact that the majority of Arabs supported Iran in the war, "ethnic Arabs complain that, as a result of their divided loyalties during the Iran–Iraq War

The Iran–Iraq War was an armed conflict between Iran and Iraq that lasted from September 1980 to August 1988. It began with the Iraqi invasion of Iran and lasted for almost eight years, until the acceptance of United Nations Security Council ...

, they are viewed more than ever by the clerical regime in Tehran as a potential fifth column

A fifth column is any group of people who undermine a larger group or nation from within, usually in favor of an enemy group or another nation. According to Harris Mylonas and Scott Radnitz, "fifth columns" are “domestic actors who work to un ...

, and suffer from a policy of discrimination." However, Iran's Arab population played an important role in defending Iran during the Iran-Iraq War and most refused to heed Saddam Hussein's call for an uprising and instead fought against their fellow Arabs. Furthermore, Iran's former defense minister Ali Shamkhani

Ali Shamkhani (Persian: , born 29 September 1955) is an Iranian two-star general. He is the secretary of the Supreme National Security Council of Iran.

Early life and education

Shamkhani was born on 29 September 1955 in Ahvaz, Khuzestan. His f ...

, a Khuzestan

Khuzestan Province (also spelled Xuzestan; fa, استان خوزستان ''Ostān-e Xūzestān'') is one of the 31 provinces of Iran. It is in the southwest of the country, bordering Iraq and the Persian Gulf. Its capital is Ahvaz and it covers ...

i Arab, was chief commander of the ground force during the Iran-Iraq War as well as serving as first deputy commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC; fa, سپاه پاسداران انقلاب اسلامی, Sepāh-e Pāsdārān-e Enghelāb-e Eslāmi, lit=Army of Guardians of the Islamic Revolution also Sepāh or Pasdaran for short) is a branch o ...

.

The Arab minority of southern Iran has been subject to discriminations, persecution in Iran. In a report published in February 2006, Amnesty International stated that the "Arab population of Iran is one of the most economically and socially deprived in Iran" and that Arabs have "reportedly been denied state employment under the ''gozinesh'' ob placementcriteria."

Critics of such reports have pointed out that they are often based on sketchy sources and are not always to be trusted at face value (see: Criticism of human rights reports on Khuzestan). Furthermore, critics point out that Arabs have social mobility in Iran, with a number of famous Iranians from the worlds of arts, sport, literature, and politics having Arab origins (see: Iranian Arabs

Iranian Arabs ( ar, عرب إيران ''ʿArab Īrān''; fa, عربهای ايران ''Arabhāye Irān'') are the Arab inhabitants of Iran who speak Arabic as their native language. In 2008, Iranian Arabs comprised about 1.6 million people, ...

) illustrating Arab-Iranian participation in Iranian economics, society, and politics. They contend that Khuzestan province, where most of Iran's Arabs live, is actually one of the more economically advanced provinces of Iran, more so than many of the Persian-populated provinces.

Some critics of the Iranian government contend that it is carrying out a policy of anti-Arab ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

. While there has been large amounts of investment in industrial projects such as the ''Razi Petrochemical Complex'', local universities, and other national projects such as hydroelectric dams (such as the Karkheh Dam

The Karkheh Dam ( fa, سد کرخه) is a large multi-purpose earthen embankment dam built in Iran on the Karkheh River in 2001 by the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC).

The dam is in the northwestern province of Khūzestān, the closest ...

, which cost $700 million to construct) and nuclear power plants, many critics of Iran's economic development policies have pointed to the poverty suffered by Arabs in Khuzestan as proof of an anti-Arab policy agenda. Following his visit to Khuzestan in July 2005, UN Special Rapporteur for Adequate Housing Miloon Kothari spoke of how up to 250,000 Arabs had been displaced by such industrial projects and noted the favorable treatment given to settlers from Yazd

Yazd ( fa, یزد ), formerly also known as Yezd, is the capital of Yazd Province, Iran. The city is located southeast of Isfahan. At the 2016 census, the population was 1,138,533. Since 2017, the historical city of Yazd is recognized as a Worl ...

compared to the treatment of local Arabs.

However, it is also true that non-Arab provinces such as Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad Province, Sistan and Baluchestan Province, and neighboring Īlām Province also suffer high levels of poverty, indicating that government policy is not disadvantaging Arabs alone but other regions, including some with large ethnically Persian populations. Furthermore, most commentators agree that Iran's state-controlled and highly subsidized economy is the main reason behind the inability of the Iranian government to generate economic growth and welfare at ground levels in all cities across the nation, rather than a state ethnic policy targeted specifically at Arabs; Iran is ranked 156th on The Heritage Foundation

The Heritage Foundation (abbreviated to Heritage) is an American conservative think tank based in Washington, D.C. that is primarily geared toward public policy. The foundation took a leading role in the conservative movement during the presiden ...

's 2006 Index of Economic Freedom

The ''Index of Economic Freedom'' is an annual index and ranking created in 1995 by The Heritage Foundation and ''The Wall Street Journal'' to measure the degree of economic freedom in the world's nations. The creators of the index claim to tak ...

.

In the Iranian education system, after primary education cycle (grades 1-5 for children 6 to 11 years old), passing some Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

courses is mandatory until the end of secondary education cycle (grade 6 to Grade 12, from age 11 to 17). In higher education systems (universities), passing Arabic language courses is selective.

Persians use slurs like "Tazi Kaseef" (lit. ''Dirty Taazi''), "Arabe malakh-khor" (عرب ملخخور) (lit. ''Locust-eater Arab''), "soosmar-khor" (سوسمارخور) (''lizard eater'') and call Arabs "پابرهنه" (lit. ''barefoot''), "بیتمدن" (lit. ''uncivilized''), "وحشی" (lit. ''barbarians'') and "زیرصحرایی" (lit ''sub-saharan''). Anti-Islamist government Persians refer to Persian Islamic Republic supporters from Hezbollahi families as Arab-parast (عربپرست) (lit. ''Arab Worshippper''). Arabs use slurs against Persians by calling them ''Fire-worshipers'' and ''majoos'', "Majus

''Majūs'' (Arabic: مجوس) or ''Magūs'' (Persian: مگوش) was originally a term meaning Zoroastrians (and specifically, Zoroastrian priests). It was a technical term, meaning magus, and like its synonym ''gabr'' (of uncertain etymology) ori ...

" (مجوس) ( Zoroastrians, Magi

Magi (; singular magus ; from Latin ''magus'', cf. fa, مغ ) were priests in Zoroastrianism and the earlier religions of the western Iranians. The earliest known use of the word ''magi'' is in the trilingual inscription written by Darius th ...

).

Negative views Persians have of Arabs include eating habits such as Arabs eating lizards.

In Iran, there is a saying, ''The Arab of the desert eats locusts, while the dogs of Isfahan drink ice-cold water.'' (). In Iran "to be outright Arab" () means "to be a complete idiot".

Relations are uneasy between specifically Iran and the Persian Gulf Arab countries in particular. Persians and Arabs dispute the name of the Persian Gulf. The Greater and Lesser Tunbs

(Tonb-e Bozorg or Tonb-e Kuchak) ar, طنب الكبرى وطنب الصغرى (Tunb el-Kubra and Tunb el-Sughra)

, location = Persian Gulf

, coordinates = Greater: Lesser:

, archipelago =

, total_islands = 2

, major_is ...

are disputed between the two countries. A National Geographic reporter who interviewed Iranians reported that many of them frequently said ''We are not Arabs!" "We are not terrorists!"''.

The Iranian rap artist Behzad Pax released a song in 2015 called "Arab-Kosh" (عربكش) (Arab-killer) which was widely reported on the Arab media who claimed that it was released with the approval of the Iranian Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. The Iranian Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance denied that it gave approval to the song and condemned it as a product of a "sick mind".

Israel

As a consequence of theArab–Israeli conflict

The Arab–Israeli conflict is an ongoing intercommunal phenomenon involving political tension, military conflicts, and other disputes between Arab countries and Israel, which escalated during the 20th century, but had mostly faded out by the ...

, there is a certain level of hostility between sections of the Jewish and Arab societies in Israel. Many Israeli Jews oppose mixed relationships, particularly between Jewish women and Arab men. A group of men in Pisgat Ze'ev

Pisgat Ze'ev ( he, פסגת זאב, lit. ''Ze'ev's Peak'') is an Israeli settlement in East Jerusalem and the largest residential neighborhood in Jerusalem with a population of over 50,000. Pisgat Ze'ev was established by Israel as one of the ci ...

started patrolling the neighborhood to stop Jewish women from dating Arab men. The municipality of Petah Tikva

Petah Tikva ( he, פֶּתַח תִּקְוָה, , ), also known as ''Em HaMoshavot'' (), is a city in the Central District (Israel), Central District of Israel, east of Tel Aviv. It was founded in 1878, mainly by Haredi Judaism, Haredi Jews of ...

has a telephone hotline to inform on Jewish girls who date Arab men, as well as a psychological counseling service. Kiryat Gat

Kiryat Gat, also spelled Qiryat Gat ( he, קִרְיַת גַּת), is a city in the Southern District of Israel. It lies south of Tel Aviv, north of Beersheba, and from Jerusalem. In it had a population of . The city hosts one of the most a ...

launched a school programme to warn Jewish girls against dating local Bedouin men.

Geography textbooks used in Israeli schools were found to portray Arabs as primitive and backwards, with the Nakba

Clickable map of Mandatory Palestine with the depopulated locations during the 1947–1949 Palestine war.

The Nakba ( ar, النكبة, translit=an-Nakbah, lit=the "disaster", "catastrophe", or "cataclysm"), also known as the Palestinian Ca ...

, the destruction of Palestinian society in the 1948 Palestine war

The 1948 Palestine war was fought in the territory of what had been, at the start of the war, British-ruled Mandatory Palestine. It is known in Israel as the War of Independence ( he, מלחמת העצמאות, ''Milkhemet Ha'Atzma'ut'') and ...

, disregarded entirely. History textbooks likewise portrayed the Palestinian population negatively, showing them as primitive and collectively to be an enemy. Contrasted with the portrayal of Jews, who were shown to be heroic and progressive, Israeli textbooks delegitimized Arabs and used negative stereotyping of Arabs nearly uniformly.

The Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu (; , singular ) are nomadic Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. The Bedouin originated in the Syrian Desert and A ...

representatives submitted a report to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

claiming that they are not treated as equal citizens and Bedouin towns are not provided the same level of services, land and water as Jewish towns of the same size are. The city of Beersheba

Beersheba or Beer Sheva, officially Be'er-Sheva ( he, בְּאֵר שֶׁבַע, ''Bəʾēr Ševaʿ'', ; ar, بئر السبع, Biʾr as-Sabʿ, Well of the Oath or Well of the Seven), is the largest city in the Negev desert of southern Israel. ...

refused to recognize a Bedouin holy site despite a High Court recommendation.

In 1994, a Jewish settler in the West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

and follower of the Kach party, Baruch Goldstein

Baruch Kopel Goldstein ( he, ברוך קופל גולדשטיין; born Benjamin Carl Goldstein; December 9, 1956 – February 25, 1994) was an Israeli-American mass murderer, religious extremist, and physician who perpetrated the 1994 terrorist ...

, massacred

A massacre is the killing of a large number of people or animals, especially those who are not involved in any fighting or have no way of defending themselves. A massacre is generally considered to be morally unacceptable, especially when per ...

29 Palestinian Muslim worshipers at the Cave of the Patriarchs

, alternate_name = Tomb of the Patriarchs, Cave of Machpelah, Sanctuary of Abraham, Ibrahimi Mosque (Mosque of Abraham)

, image = Palestine Hebron Cave of the Patriarchs.jpg

, alt =

, caption = Southern view of the complex, 2009

, map ...

in Hebron

Hebron ( ar, الخليل or ; he, חֶבְרוֹן ) is a Palestinian. city in the southern West Bank, south of Jerusalem. Nestled in the Judaean Mountains, it lies above sea level. The second-largest city in the West Bank (after East J ...

. It was known that, prior to the massacre, Goldstein, a physician, refused to treat Arabs, including Arab soldiers with the Israeli army. During his funeral, a rabbi declared that even one million Arabs are "not worth a Jewish fingernail". Goldstein was immediately "denounced with shocked horror even by the mainstream Orthodox",The ethics of war in Asian civilizations: a comparative perspective By Torkel Brekke, Routledge, 2006, p.44 and many in Israel classified Goldstein as insane. The Israeli government condemned the massacre and made Kach illegal. The Israeli army killed a further nine Palestinians during riots following the massacre, and the Israeli government severely restricted Palestinian freedom of movement

Restrictions on the movement of Palestinians in the Israeli-occupied territories by Israel is an issue in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. According to B'Tselem, following the 1967 war, the occupied territories were proclaimed closed milit ...

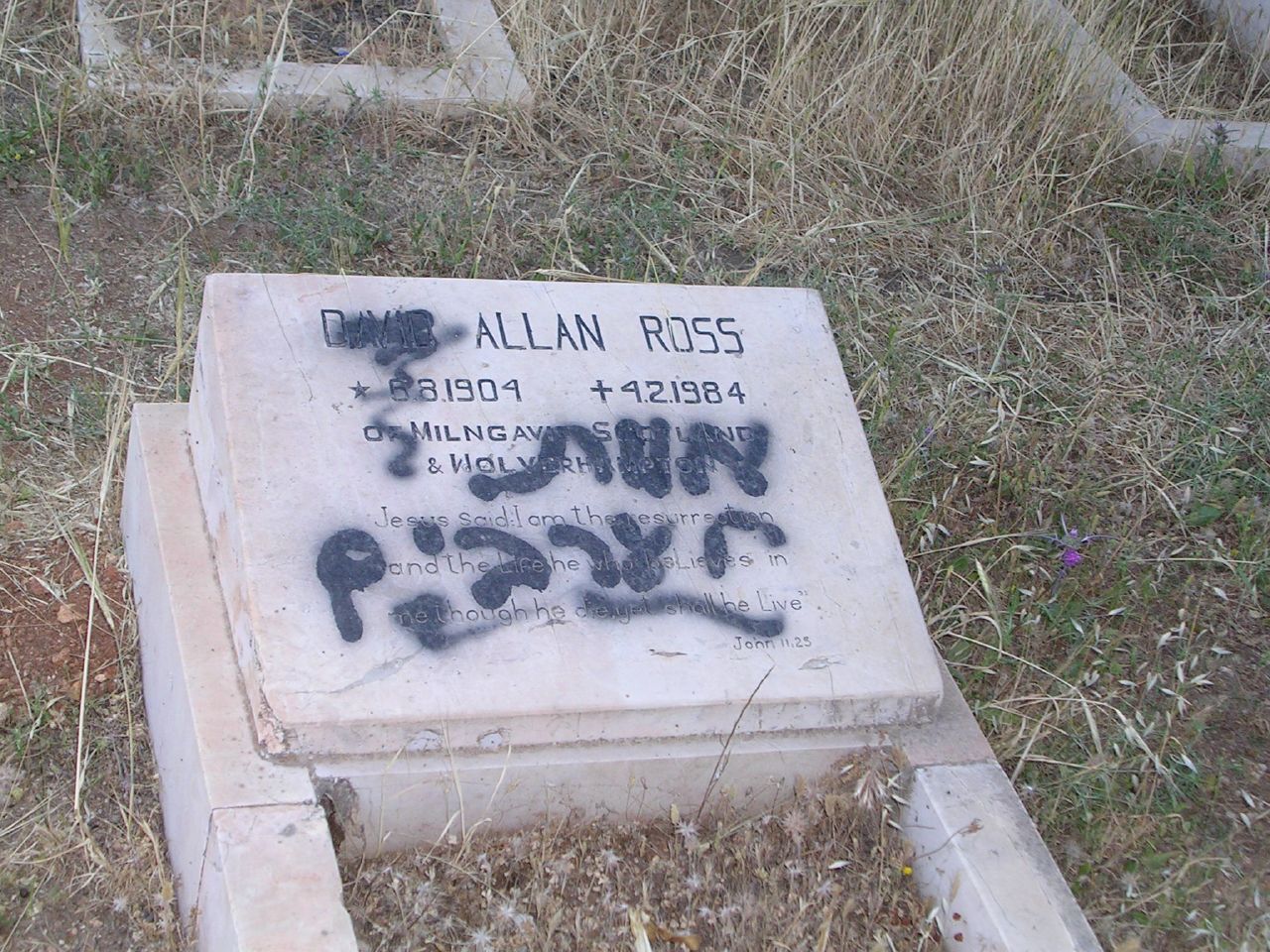

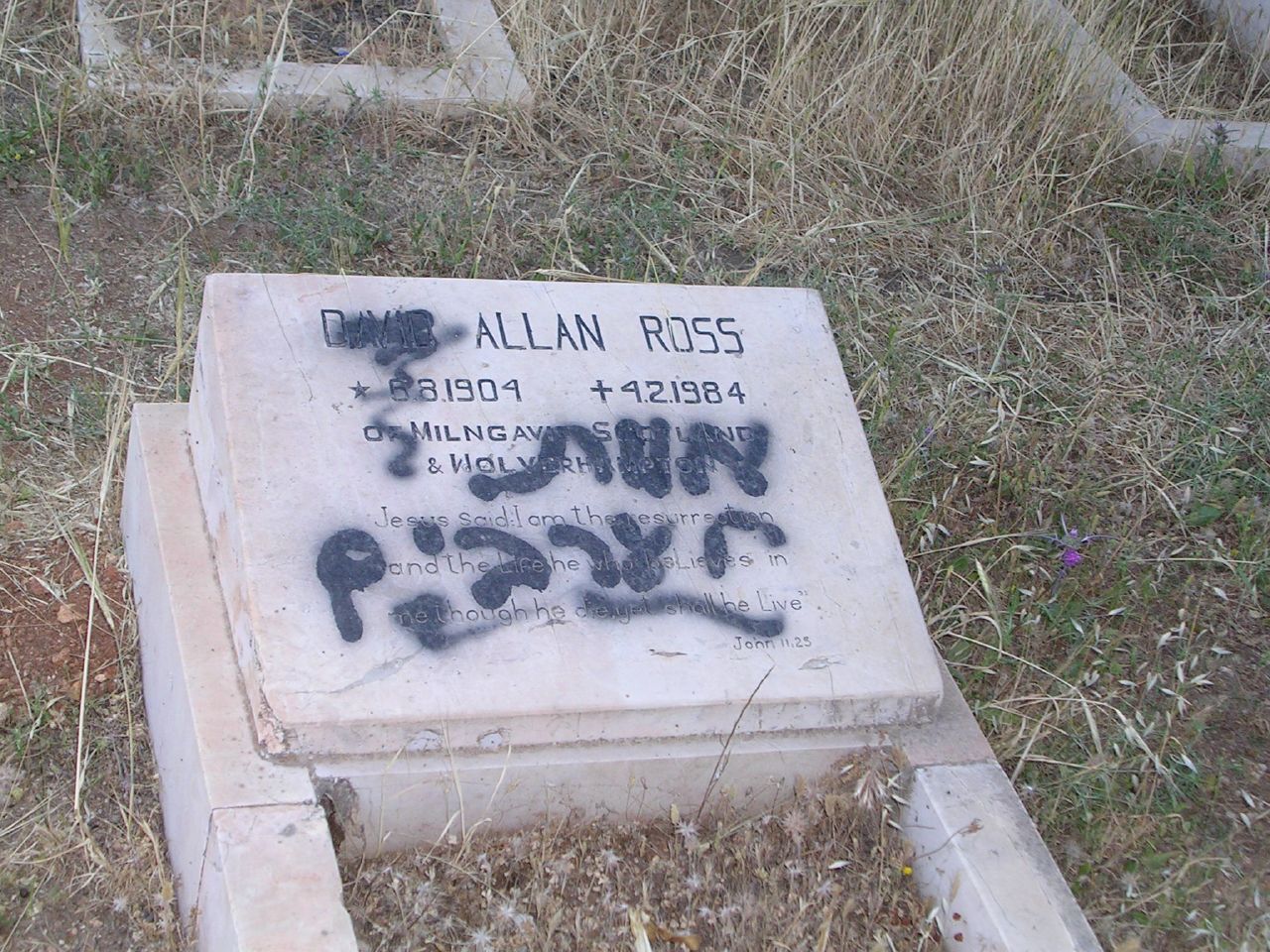

in Hebron, while letting settlers and foreign tourists roam free, although Israel also forbade a small group of Israeli settlers from entering Palestinian towns and demanded that those settlers turn in their army-issued rifles. Goldstone's grave has become a pilgrimage site for Jewish extremists.

In a number of occasions, Israeli Jewish demonstrators and rioters used racist anti-Arab slogans. For example, during the Arab riots in October 2000 events

The October 2000 protests, also known as October 2000 events, were a series of protests in Arab villages in northern Israel in October 2000 that turned violent, escalating into rioting by Israeli Arabs, which led to counter-rioting by Israeli Je ...

, Israelis counter-rioted in Nazareth

Nazareth ( ; ar, النَّاصِرَة, ''an-Nāṣira''; he, נָצְרַת, ''Nāṣəraṯ''; arc, ܢܨܪܬ, ''Naṣrath'') is the largest city in the Northern District of Israel. Nazareth is known as "the Arab capital of Israel". In ...

and Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

, throwing stones at Arabs, destroying Arab property, with some chanting "death to Arabs

Death to Arabs ( he, מוות לערבים ) is an anti-Arab slogan which is used by some Israelis and is considered a hateful, genocidal, and racist slogan. It is used in multiple contexts, such as football, graffiti, marches in Jerusalem and ...

". Some Israeli-Arab soccer players face chants from the crowd when they play such as "no Arabs, no terrorism". In the most radical event, Abbas Zakour, an Arab member of the Knesset, was stabbed and wounded by unidentified men, who shouted anti-Arab chants. The attack was described as a "hate crime

A hate crime (also known as a bias-motivated crime or bias crime) is a prejudice-motivated crime which occurs when a perpetrator targets a victim because of their membership (or perceived membership) of a certain social group or racial demograph ...

". Among the Israeli teams, Beitar Jerusalem

Beitar Jerusalem Football Club ( he, מועדון כדורגל בית"ר ירושלים, Moadon Kaduregel Beitar Yerushalayim), commonly known as Beitar Jerusalem () or simply as Beitar (), is an Israeli football club based in the city of Jeru ...

is considered emblematic of Jewish racism; the fans are infamous for their 'Death to Arabs' chant and the team has a ban on Arab players, a policy that is in violation of FIFA

FIFA (; stands for ''Fédération Internationale de Football Association'' ( French), meaning International Association Football Federation ) is the international governing body of association football, beach football and futsal. It was found ...

's guidelines, though the team has never faced suspension from the football organization. In March 2012, supporters of the team were filmed raiding a Jerusalem mall and beating up Arab employees.

The Israeli political party Yisrael Beiteinu

Yisrael Beiteinu ( he, יִשְׂרָאֵל בֵּיתֵנוּ, russian: Наш Дом Израиль, lit. ''Israel Our Home'') is a secularist, nationalist right-wing political party in Israel. The party's base was originally secular Russia ...

, whose platform includes the redrawing of Israel's borders so that 500,000 Israeli Arabs

The Arab citizens of Israel are the largest ethnic minority in the country. They comprise a hybrid community of Israeli citizens with a heritage of Palestinian citizenship, mixed religions (Muslim, Christian or Druze), bilingual in Arabic an ...

would be part of a future Palestinian State

Palestine ( ar, فلسطين, Filasṭīn), officially the State of Palestine ( ar, دولة فلسطين, Dawlat Filasṭīn, label=none), is a state located in Western Asia. Officially governed by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PL ...

, won 15 seats in the 2009 Israeli elections

9 (nine) is the natural number following and preceding .

Evolution of the Arabic digit

In the Brahmi numerals, beginning, various Indians wrote a digit 9 similar in shape to the modern closing question mark without the bottom dot. The Kshat ...

, increasing its seats by 4 compared to the 2006 Israeli elections. This policy, also known as the Lieberman Plan

The Lieberman Plan, also known in Israel as the "Populated-Area Exchange Plan", was proposed in May 2004 by Avigdor Lieberman, the leader of the Israeli political party Yisrael Beiteinu. The plan suggests an exchange of ''populated territories'' ...

, was described as "anti-Arab" by ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

''. In 2004, Yehiel Hazan

Yehiel Hazan ( he, יחיאל חזן, born 1 March 1958) is an Israeli politician. He is of a Tunisian-Jewish descent.

Political career

Hazan was born in Hadera and grew up in Or Akiva. He was elected to the Knesset in the 2003 elections as a ...

, a member of the Knesset

The Knesset ( he, הַכְּנֶסֶת ; "gathering" or "assembly") is the unicameral legislature of Israel. As the supreme state body, the Knesset is sovereign and thus has complete control of the entirety of the Israeli government (with ...

, described the Arabs as worms: "You find them everywhere like worms, underground as well as above."

In 2004, then Deputy Defense Minister

In 2004, then Deputy Defense Minister Ze'ev Boim

Ze'ev Boim ( he, זאב בוים, 30 April 1943 – 18 March 2011) was an Israeli politician. He was the mayor of Kiryat Gat before becoming a Knesset member for Likud and later Kadima. Boim was Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development, M ...

asked "What is it about Islam as a whole and the Palestinians in particular? Is it some form of cultural deprivation? Is it some genetic defect? There is something that defies explanation in this continued murderousness."

In August 2005, Israeli soldier Eden Natan-Zada traveled to an Israeli Arab town and massacred four civilians. Israeli Arabs said they would draw up a list of grievances after the terrorist

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

attack of Eden Natan-Zada

Eden Natan-Zada ( he, עדן נתן-זדה, born 9 July 1986, died 4 August 2005) was an Israeli soldier who opened fire in a bus in Shefa-Amr in northern Israel on 4 August 2005, killing four Israeli-Arabs and wounding twelve others. He was re ...

. "This was a planned terror attack and we find it extremely difficult to treat it as an individual action," Abed Inbitawi, an Israeli-Arab spokesman, told ''The Jerusalem Post''. "It marks a certain trend that reflects a growing tendency of fascism and racism in Israeli society generally as well as the establishment towards the minority Arab community," he said.

According to a 2006 poll conducted by Geocartographia for the Centre for the Struggle Against Racism, 41% of Israelis support Arab-Israeli segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

at entertainment venues, 40% believed "the state needs to support the emigration of Arab citizens", and 63% believed Arabs to be a "security and demographic threat The concept of demographic threat (or demographic bomb) is a term used in political conversation or demography to refer to population increases from within a minority ethnic or religious group in a given country that is perceived as threatening to t ...

" to Israel. The poll found that more than two thirds would not want to live in the same building as an Arab, 36% believed Arab culture to be inferior, and 18% felt hatred when they heard Arabic spoken.

In 2007, the Association for Civil Rights in Israel

The Association for Civil Rights in Israel (ACRI) (Hebrew: ; Arabic: ) was created in 1972 as an independent, non-partisan not-for-profit organization with the mission of protecting human rights and civil rights in Israel and the territories unde ...

reported that anti-Arab views had doubled, and anti-Arab racist incidents had increased by 26%. The report quoted polls that suggested 50% of Jewish Israelis do not believe Arab citizens of Israel should have equal rights, 50% said they wanted the government to encourage Arab emigration from Israel, and 75% of Jewish youths said Arabs were less intelligent and less clean than Jews. The Mossawa Advocacy Center for Arab Citizens in Israel reported a tenfold increase in racist incidents against Arabs in 2008. Jerusalem reported the highest number of incidents. The report blamed Israeli leaders for the violence, saying "These attacks are not the hand of fate, but a direct result of incitement against the Arab citizens of this country by religious, public, and elected officials."

In March 2009, following the Gaza War, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) drew criticism when several young soldiers had T-shirt

A T-shirt (also spelled tee shirt), or tee, is a style of fabric shirt named after the T shape of its body and sleeves. Traditionally, it has short sleeves and a round neckline, known as a ''crew neck'', which lacks a collar. T-shirts are general ...

s printed up privately with slogans and caricatures portraying dead babies, weeping mothers, and crumbled mosques.

In June 2009, Haaretz

''Haaretz'' ( , originally ''Ḥadshot Haaretz'' – , ) is an Israeli newspaper. It was founded in 1918, making it the longest running newspaper currently in print in Israel, and is now published in both Hebrew and English in the Berliner f ...

reported that Israel's Public Security Minister, Yitzhak Aharonovich

Yitzhak Aharonovich ( he, יצחק אהרונוביץ', born 22 August 1950) is an Israeli businessman and former politician. He served as a member of the Knesset for Yisrael Beiteinu between 2006 and 2015, and also held the posts of Minister of ...

, called an undercover police officer a "dirty Arab" whilst touring Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

.

Since the 2000s, groups such as Lehava

Lehava ( "Flame," he, למניעת התבוללות בארץ הקודש ''LiMniat Hitbolelut B'eretz HaKodesh''; Prevention of Assimilation in the Holy Land) is a far-right and Jewish supremacist organization based in Israel that strictly oppo ...

have been formed in Israel to prevent that Israeli Arab men form relationships with Jewish women. Some of the material promoted to discourage Jewish women to be with Arab men, are sanctioned by local governments and police departments. Lehava has received permission from Israeli courts to picket the weddings uniting a Palestinian and a Jewish partner.

In 2010, dozens of Israel's top rabbis

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as '' semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form o ...

went on to sign a document forbidding that Jews rent apartments to Arabs, saying that "racism originated in the Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the s ...

".

In January 2012, the Israeli High Court upheld a decision, deemed racist, preventing the Palestinian espouses of Israeli Arabs from obtaining Israeli citizenship or resident status.

A poll in 2012 revealed that racist attitudes are embraced by a large majority of Israelis. 59% of Jews said they wanted Jews to be given preference in admission to public employment, 50% wanted the state to generally treat Jews better than Arabs, and over 40% wanted separate housing for Jews and Arabs. According to the poll, 58% supported the use of the term apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

to represent Israeli policies against Arabs. The poll also showed that the majority of Israeli Jews would not want voting rights extended to Palestinians if the West Bank were annexed by Israel.

In 2013, Nazareth Illit

Nof HaGalil ( he, נוֹף הַגָּלִיל, lit. ''View of Galilee''; ar, نوف هچليل) is a city in the Northern District of Israel with a population of .

Nof HaGalil was founded in 1957 as Nazareth Illit ( he, נָצְרַת עִלִ� ...

mayor Shimon Gafsou declared that he would never allow that an Arab school, a mosque, or a church be built in his city, despite the fact that Arabs account for 18 percent of its population.

On July 2, 2014, 16-year-old Palestinian Mohammed Abu Khdeir

The kidnapping and murder of Mohammed Abu Khdeir occurred early on the morning of 2 July 2014. Khdeir, a 16-year-old Palestinian, was forced into a car by Israeli citizens on an East Jerusalem street. His family immediately reported the fact to ...

was kidnapped, beaten and burned alive, after three Israeli teenagers were kidnapped and killed in the West Bank. Khdeir's family members have blamed Israeli Government anti-Arab hate speech for inciting the murder and rejected the PM's condolence message, as well as a visit by then President Shimon Peres

Shimon Peres (; he, שמעון פרס ; born Szymon Perski; 2 August 1923 – 28 September 2016) was an Israeli politician who served as the eighth prime minister of Israel from 1984 to 1986 and from 1995 to 1996 and as the ninth president of ...

. Two Israeli minors were found guilty of Khdeirs' murder and sentenced to life and 21 years imprisonment respectively.

During the 2015 Israeli legislative election

Early elections for the twentieth Knesset were held in Israel on 17 March 2015. Disagreements within the governing coalition, particularly over the budget and a "Jewish state" proposal, led to the dissolution of the government in December 2 ...

, Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

Benjamin Netanyahu

Benjamin "Bibi" Netanyahu (; ; born 21 October 1949) is an Israeli politician who served as the ninth prime minister of Israel from 1996 to 1999 and again from 2009 to 2021. He is currently serving as Leader of the Opposition and Chairman of ...

complained, in a video statement to supporters, that his left-wing opponents were supposedly sending Israeli Arabs to vote in droves, in a statement that was widely condemned as racist, including by the US government. Netanyahu went on to win the elections against poll predictions, and several commentators and pollster imputed his victory to his last-minute attack on Israeli Arab voters. During election campaign, then Foreign Affairs Minister Avigdor Lieberman proposed beheading Israeli Arabs that are "disloyal" to the state.

Niger

In October 2006, the government ofNiger

)

, official_languages =

, languages_type = National languagesMahamid

The Mahameed ( ar, المحاميد), and sometimes the Mahmid or the Mahammeed, are an Arab tribe that traces its origins to the Khawlaniyah al-Qahtaniyah Harb The majority of them resided originally in the Hijaz, between Mecca and Medina, an ...

Baggara

The Baggāra ( ar, :wikt:بقار#Etymology 2, البَقَّارَة "heifer herder") or Chadian Arabs are a Nomad, nomadic confederation of people of mixed Arabs, Arab and Arabization, Arabized Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous African a ...

Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

living in the Diffa

Diffa is a city and Urban Commune in the extreme southeast of Niger, near the border with Nigeria. It is the administrative seat of both Diffa Region, and the smaller Diffa Department.Geels, Jolijn, (2006) ''Bradt Travel Guide - Niger'', pgs. 2 ...

region of eastern Niger to Chad

Chad (; ar, تشاد , ; french: Tchad, ), officially the Republic of Chad, '; ) is a landlocked country at the crossroads of North and Central Africa. It is bordered by Libya to the north, Sudan to the east, the Central African Republic ...

. This population numbered about 150,000. While the government was rounding Arabs in preparation for the deportation, two girls died, reportedly after fleeing government forces, and three women suffered miscarriages. Niger's government had eventually suspended the controversial decision to deport Arabs.

Pakistan

Wealthy Gulf Arabs hunting the endangered Houbara bustard in Pakistan for consumption as anaphrodisiac

An aphrodisiac is a substance that increases sexual desire, sexual attraction, sexual pleasure, or sexual behavior. Substances range from a variety of plants, spices, foods, and synthetic chemicals. Natural aphrodisiacs like cannabis or cocain ...

has led to negative sentiment against wealthy Arab shaykhs in Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

.

Turkey

Turkey has a history of strong anti-Arabism. During theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, the Arabs were treated as just second-class subjects and suffered from immense discrimination by the Ottoman Turkish rulers, in addition, most of government's main positions were either held by Turks or non-Arab people, except for the Emirate of Hejaz under Ottoman rule. Future policy of anti-Arab sentiment, including the process of Turkification

Turkification, Turkization, or Turkicization ( tr, Türkleştirme) describes a shift whereby populations or places received or adopted Turkic attributes such as culture, language, history, or ethnicity. However, often this term is more narrowly ...

, led to the Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية الكبرى, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On t ...

against the Ottomans.

Because of the Syrian refugee crisis, anti-Arabism has intensified. Haaretz

''Haaretz'' ( , originally ''Ḥadshot Haaretz'' – , ) is an Israeli newspaper. It was founded in 1918, making it the longest running newspaper currently in print in Israel, and is now published in both Hebrew and English in the Berliner f ...

reported that anti-Arabian racism in Turkey mainly affects two groups; tourists from the Gulf who are characterized as "rich and condescending" and the Syrian refugees in Turkey. Haaretz also reported that anti-Syrian sentiment in Turkey is metastasizing into a general hostility toward all Arabs including the Palestinians. Deputy Chairman of the Good Party

The Good Party ( Turkish: ''İyi Parti'') is a nationalist, national conservative, Kemalist, and liberal democrat political party in Turkey, established on 25 October 2017 by its current leader Meral Akşener. Their fraternal party is the liber ...

warned that Turkey risked becoming "a Middle Eastern country" because of the influx of refugees.

Outside historical enmity, anti-Arabism is also widespread in Turkish media, as Turkish media and education curriculum associating Arabs with backwardness. This has continued influencing modern Turkish historiography and the crusade of Turkish soft power, with Arabs being frequently stereotyped as evil, uncivilized, terrorists, incompetent, stupid, etc. This depiction is frequently used in contrast to the alleged depiction of Turkic people as "noble, generous, fearsome, loyal, brave and spirited warriors".

Anti-Arab sentiment is also further fueled by ultranationalist groups, including the Grey Wolves

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the gray wolf or grey wolf, is a large canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, and gray wolves, as popularly u ...

and pan-Turkist nationalist parties, who called for invasions on the Arab World

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western A ...

's Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

and Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, to prevent the ongoing Arab persecution of its Turkic populations in many Arab countries of the Middle East. Subsequently, Turkey has begun a series of persecuting its Arab population, as well as desire to recreate the new Turkish border.

In recent years, anti-Arabism has been linked with various attempts by Arab leaders to meddle into Turkish affairs, Turkey's alliance with Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, which led to the discrimination against Arabs in Turkey grow.

United Kingdom

In 2008, a Qatari 16-year-old was killed in a racially motivated attack inHastings, East Sussex

Hastings () is a large seaside town and Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east to the county town of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, ...

.

United States

William A. Dorman, writing in the compendium ''The United States and the Middle East: A Search for New Perspectives'' (1992), notes that whereas "anti-Semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

is no longer socially acceptable, at least among the educated classes n such social sanctions exist for anti-Arabism." Public opinion polls demonstrate that anti-Arabism in the United States is increasing significantly.

Prominent Russian-American

Russian Americans ( rus, русские американцы, r=russkiye amerikantsy, p= ˈruskʲɪje ɐmʲɪrʲɪˈkant͡sɨ) are Americans of full or partial Russians, Russian ancestry. The term can apply to recent Russian diaspora, Russian imm ...

Objectivist

Objectivism is a philosophical system developed by Russian-American writer and philosopher Ayn Rand. She described it as "the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement ...

author, scholar and philosopher Ayn Rand