Anthony Trollope on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

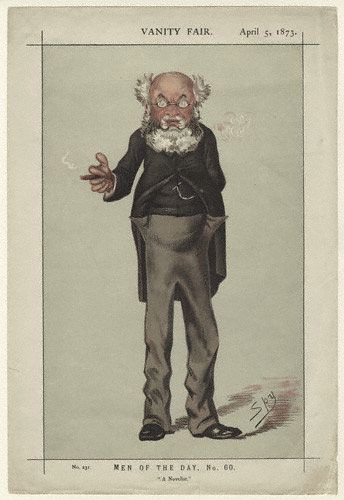

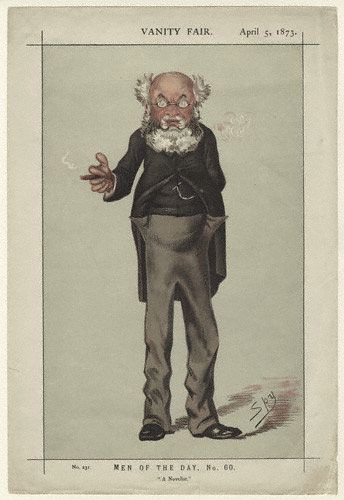

Anthony Trollope (; 24 April 1815 – 6 December 1882) was an English

Born in London, Anthony attended Harrow School as a free

Born in London, Anthony attended Harrow School as a free

''An Autobiography''.

Retrieved 2 July 2010.

Retrieved 2 July 2010.

Retrieved 2 July 2010. At the Post Office, he acquired a reputation for unpunctuality and insubordination. A debt of £12 to a tailor fell into the hands of a moneylender and grew to over £200; the lender regularly visited Trollope at his work to demand payments. Trollope hated his work, but saw no alternative and lived in constant fear of dismissal.

In 1841, an opportunity to escape offered itself. A postal surveyor's clerk in central Ireland was reported as being incompetent and in need of replacement. The position was not regarded as a desirable one at all; but Trollope, in debt and in trouble at his office, volunteered for it; and his supervisor,

In 1841, an opportunity to escape offered itself. A postal surveyor's clerk in central Ireland was reported as being incompetent and in need of replacement. The position was not regarded as a desirable one at all; but Trollope, in debt and in trouble at his office, volunteered for it; and his supervisor,

Chapter 4.

Retrieved 2 July 2010. His salary and travel allowance went much further in Ireland than they had in London, and he found himself enjoying a measure of prosperity. He took up fox hunting, which he pursued enthusiastically for the next three decades. His professional role as a post-office surveyor brought him into contact with Irish people, and he found them pleasant company: "The Irish people did not murder me, nor did they even break my head. I soon found them to be good-humoured, clever—the working classes very much more intelligent than those of England—economical and hospitable." At the watering place of

Significantly, many of his earliest novels have Ireland as their setting—natural enough given that he wrote them or thought them up while he was living and working in Ireland, but unlikely to enjoy warm critical reception, given the contemporary English attitude towards Ireland.Edwards, Owen Dudley. "Anthony Trollope, the Irish Writer. ''Nineteenth-Century Fiction'', Vol. 38, No. 1 (June 1983), p. 1 Critics have pointed out that Trollope's view of Ireland separates him from many of the other Victorian novelists. Other critics claimed that Ireland did not influence Trollope as much as his experience in England, and that the society in Ireland harmed him as a writer, especially since Ireland was experiencing the Great Famine during his time there. However, these critics have been accused of bigoted opinions against Ireland who fail or refuse to acknowledge both Trollope's true attachment to the country and the country's capacity as a rich literary field.

Trollope published four novels about Ireland. Two were written during the Great Famine, while the third deals with the famine as a theme (''

Significantly, many of his earliest novels have Ireland as their setting—natural enough given that he wrote them or thought them up while he was living and working in Ireland, but unlikely to enjoy warm critical reception, given the contemporary English attitude towards Ireland.Edwards, Owen Dudley. "Anthony Trollope, the Irish Writer. ''Nineteenth-Century Fiction'', Vol. 38, No. 1 (June 1983), p. 1 Critics have pointed out that Trollope's view of Ireland separates him from many of the other Victorian novelists. Other critics claimed that Ireland did not influence Trollope as much as his experience in England, and that the society in Ireland harmed him as a writer, especially since Ireland was experiencing the Great Famine during his time there. However, these critics have been accused of bigoted opinions against Ireland who fail or refuse to acknowledge both Trollope's true attachment to the country and the country's capacity as a rich literary field.

Trollope published four novels about Ireland. Two were written during the Great Famine, while the third deals with the famine as a theme (''

Chapter 5.

Retrieved 2 July 2010. In the course of it, he visited Salisbury Cathedral; and there, according to his autobiography, he conceived the plot of '' He immediately began work on '' Barchester Towers'', the second Barsetshire novel;Trollope (1883).

He immediately began work on '' Barchester Towers'', the second Barsetshire novel;Trollope (1883).

Chapter 6.

Retrieved 2 July 2010. upon its publication in 1857,Trollope (1883).

Retrieved 2 July 2010. he received an advance payment of £100 (about £ in consumer pounds) against his share of the profits. Like ''The Warden'', ''Barchester Towers'' did not obtain large sales, but it helped to establish Trollope's reputation. In his autobiography, Trollope writes, "It achieved no great reputation, but it was one of the novels which novel readers were called upon to read." For the following novel, ''

Chapter 8.

Retrieved 2 July 2010. Later in that year he moved to Waltham Cross, about from London in Hertfordshire, where he lived until 1871. In late 1859, Trollope learned of preparations for the release of the ''

Chapter 15.

Retrieved 2 July 2010.

chapter 16.

Retrieved 21 May 2010. As a civil servant, however, he was ineligible for such a position. His resignation from the Post Office removed this disability, and he almost immediately began seeking a seat for which he might stand.Super, R. H. (1988).

''The Chronicler of Barsetshire''.

University of Michigan Press.

pp. 251–5.

Retrieved 19 May 2010. In 1868, he agreed to stand as aBritish History Online.

Retrieved 20 May 2010. The task of a Liberal candidate was not to win the election, but to give the

Trollope returned to Australia in 1875 to help his son close down his failed farming business. He found that the resentment created by his accusations of bragging remained. Even when he died in 1882, Australian papers still "smouldered", referring yet again to these accusations, and refusing to fully praise or recognize his achievements.Starck, p. 21

In the late 1870's, Trollope furthered his travel writing career by visiting

Trollope returned to Australia in 1875 to help his son close down his failed farming business. He found that the resentment created by his accusations of bragging remained. Even when he died in 1882, Australian papers still "smouldered", referring yet again to these accusations, and refusing to fully praise or recognize his achievements.Starck, p. 21

In the late 1870's, Trollope furthered his travel writing career by visiting

Trollope's popularity and critical success diminished in his later years, but he continued to write prolifically, and some of his later novels have acquired a good reputation. In particular, critics who concur that the book was not popular when published, generally acknowledge the sweeping satire ''

Trollope's popularity and critical success diminished in his later years, but he continued to write prolifically, and some of his later novels have acquired a good reputation. In particular, critics who concur that the book was not popular when published, generally acknowledge the sweeping satire ''

online

* Cockshut, O. J. (1955). ''Anthony Trollope: A Critical Study'', London: Collins. * Escott, T. H. S. (1913)

''Anthony Trollope, his Work, Associates and Literary Originals''

John Lane: The Bodley Head. * Gerould, Winifred and James (1948). ''A Guide to Trollope'', Princeton University Press. * Glendinning, Victoria (1992). ''Anthony Trollope'', Alfred A. Knopf. * * Hall, N. John (1991). ''Trollope: A Biography'', Clarendon Press. * Kincaid, James R. (1977). ''The Novels of Anthony Trollope'', Oxford: Clarendon Press. * MacDonald, Susan (1987). ''Anthony Trollope'', Twayne Publishers. * Mullen, Richard (1990). ''Anthony Trollope: A Victorian in his World'', Savannah: Frederic C. Beil. * Polhemus, Robert M. (1966). ''The Changing World of Anthony Trollope'', University of California Press. * Pollard, Arthur (1978). ''Anthony Trollope'', Routledge & Kegan Paul, Limited. * Pope-Hennessy, James (1971). ''Anthony Trollope'', Jonathan Cape. * * Terry, R.C., ed. (1999). ''Oxford Reader's Companion to Trollope'', Oxford University Press. * Smalley, Donald (1969). ''Anthony Trollope: The Critical Heritage'', Routledge. * Walpole, Hugh (1928)

''Anthony Trollope''

New York: The Macmillan Company.

Anthony Trollope

—

Anthony Trollope

at the British Library * Anthony Trollope Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Collection of portraits of Trollope at the National Portrait Gallery, London

;Other links

Trollope Society website

Classical references

in the Barsetshire series of novels, researched by students from

Vanity Fair – Mrs. Trollope's America

The Trollope Prize

at the University of Kansas.

The Fortnightly Review Prospectus

by Anthony Trollope {{DEFAULTSORT:Trollope, Anthony 1815 births 1882 deaths 19th-century British dramatists and playwrights 19th-century British non-fiction writers 19th-century British novelists 19th-century British short story writers 19th-century English dramatists and playwrights 19th-century English non-fiction writers 19th-century English novelists 19th-century essayists British anti-poverty advocates British anti-capitalists British autobiographers British biographers British humorists British literary critics British male dramatists and playwrights British male essayists British male novelists British male short story writers British satirists British short story writers British travel writers Burials at Kensal Green Cemetery Civil servants in the General Post Office Cultural critics English essayists Freemasons of the United Grand Lodge of England Literacy and society theorists Literary theorists People educated at Harrow School People educated at Winchester College People from South Harting British social commentators Social critics Victorian novelists Writers about activism and social change Writers from London

novelist

A novelist is an author or writer of novels, though often novelists also write in other genres of both fiction and non-fiction. Some novelists are professional novelists, thus make a living writing novels and other fiction, while others asp ...

and civil servant of the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

. Among his best-known works is a series of novels collectively known as the '' Chronicles of Barsetshire'', which revolves around the imaginary county of Barsetshire

Barsetshire is a fictional English county created by Anthony Trollope in the series of novels known as the Chronicles of Barsetshire. The county town and cathedral city is Barchester. Other towns in the novels include Silverbridge, Hogglestock an ...

. He also wrote novels on political, social, and gender issues, and other topical matters.

Trollope's literary reputation dipped somewhat during the last years of his life, but he had regained the esteem of critics by the mid-20th century.

Biography

Anthony Trollope was the son of barrister Thomas Anthony Trollope and the novelist andtravel writer

The genre of travel literature encompasses outdoor literature, guide books, nature writing, and travel memoirs.

One early travel memoirist in Western literature was Pausanias, a Greek geographer of the 2nd century CE. In the early modern per ...

Frances Milton Trollope

Frances Milton Trollope, also known as Fanny Trollope (10 March 1779 – 6 October 1863), was an English novelist who wrote as Mrs. Trollope or Mrs. Frances Trollope. Her book, ''Domestic Manners of the Americans'' (1832), observations from a t ...

. Though a clever and well-educated man and a Fellow of New College, Oxford, Thomas Trollope failed at the Bar due to his bad temper. Ventures into farming proved unprofitable, and he did not receive an expected inheritance when an elderly childless uncle remarried and had children. Thomas Trollope was the son of Rev. (Thomas) Anthony Trollope, rector of Cottered

Cottered is a village and civil parish west of Buntingford and east of Baldock in the East Hertfordshire District of Hertfordshire in England. It had a population of 634 in 2001, increasing to 659 at the 2011 Census.

Cottered is home to a Ja ...

, Hertfordshire, himself the sixth son of Sir Thomas Trollope, 4th Baronet. The baronetcy later came to descendants of Anthony Trollope's second son, Frederic. As a son of landed gentry, Thomas Trollope wanted his sons to be raised as gentlemen and to attend Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

or Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

. Anthony Trollope suffered much misery in his boyhood owing to the disparity between the privileged background of his parents and their comparatively small means.

day pupil

A boarding school is a school where pupils live within premises while being given formal instruction. The word "boarding" is used in the sense of " room and board", i.e. lodging and meals. As they have existed for many centuries, and now exte ...

for three years from the age of seven because his father's farm, acquired for that reason, lay in that neighbourhood. After a spell at a private school at Sunbury, he followed his father and two older brothers to Winchester College

Winchester College is a public school (fee-charging independent day and boarding school) in Winchester, Hampshire, England. It was founded by William of Wykeham in 1382 and has existed in its present location ever since. It is the oldest of ...

, where he remained for three years. He returned to Harrow as a day-boy to reduce the cost of his education. Trollope had some very miserable experiences at these two public schools. They ranked as two of the élite schools in England, but Trollope had no money and no friends, and was bullied a great deal. At the age of 12 he fantasised about suicide. He also daydreamed, constructing elaborate imaginary worlds.

In 1827, his mother Frances Trollope

Frances Milton Trollope, also known as Fanny Trollope (10 March 1779 – 6 October 1863), was an English novelist who wrote as Mrs. Trollope or Mrs. Frances Trollope. Her book, '' Domestic Manners of the Americans'' (1832), observations from a ...

moved to America with Trollope's three younger siblings, to Nashoba Commune

The Nashoba Community was an experimental project of Frances "Fanny" Wright, initiated in 1825 to educate and emancipate slaves. It was located in a 2,000-acre (8 km²) woodland on the side of present-day Germantown, Tennessee, a Memphis su ...

. After that failed, she opened a bazaar in Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

, which proved unsuccessful. Thomas Trollope joined them for a short time before returning to the farm at Harrow, but Anthony stayed in England throughout. His mother returned in 1831 and rapidly made a name for herself as a writer, soon earning a good income. His father's affairs, however, went from bad to worse. He gave up his legal practice entirely and failed to make enough income from farming to pay rents to his landlord, Lord Northwick. In 1834, he fled to Belgium to avoid arrest for debt. The whole family moved to a house near Bruges

Bruges ( , nl, Brugge ) is the capital and largest city of the province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium, in the northwest of the country, and the sixth-largest city of the country by population.

The area of the whole city a ...

, where they lived entirely on Frances's earnings.

In Belgium, Anthony was offered a commission in an Austrian cavalry regiment. To accept it, he needed to learn French and German; he had a year in which to acquire these languages. To learn them without expense to himself and his family, he took a position as an usher (assistant master) in a school in Brussels, which position made him the tutor of 30 boys. After six weeks of this, however, he received an offer of a clerkship in the General Post Office, obtained through a family friend. He returned to London in the autumn of 1834 to take up this post.Trollope, Anthony (1883).''An Autobiography''.

Retrieved 2 July 2010.

Retrieved 2 July 2010.

Retrieved 2 July 2010. At the Post Office, he acquired a reputation for unpunctuality and insubordination. A debt of £12 to a tailor fell into the hands of a moneylender and grew to over £200; the lender regularly visited Trollope at his work to demand payments. Trollope hated his work, but saw no alternative and lived in constant fear of dismissal.

Move to Ireland

In 1841, an opportunity to escape offered itself. A postal surveyor's clerk in central Ireland was reported as being incompetent and in need of replacement. The position was not regarded as a desirable one at all; but Trollope, in debt and in trouble at his office, volunteered for it; and his supervisor,

In 1841, an opportunity to escape offered itself. A postal surveyor's clerk in central Ireland was reported as being incompetent and in need of replacement. The position was not regarded as a desirable one at all; but Trollope, in debt and in trouble at his office, volunteered for it; and his supervisor, William Maberly

William is a male given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norm ...

, eager to be rid of him, appointed him to the position.

Trollope based himself in Banagher

Banagher ( or ''Beannchar na Sionna'') is a town in Ireland, located in the midlands, on the western edge of County Offaly in the province of Leinster, on the banks of the River Shannon. It had a population of 3,000 at the height of its econ ...

, King's County, with his work consisting largely of inspection tours in Connaught

Connacht ( ; ga, Connachta or ), is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the west of Ireland. Until the ninth century it consisted of several independent major Gaelic kingdoms (Uí Fiachrach, Uí Briúin, Uí Maine, Conmhaícne, and Delbhn ...

. Although he had arrived with a bad reference

Reference is a relationship between objects in which one object designates, or acts as a means by which to connect to or link to, another object. The first object in this relation is said to ''refer to'' the second object. It is called a '' name'' ...

from London, his new supervisor resolved to judge him on his merits; by Trollope's account, within a year he had the reputation of a valuable public servant.Trollope (1883)Chapter 4.

Retrieved 2 July 2010. His salary and travel allowance went much further in Ireland than they had in London, and he found himself enjoying a measure of prosperity. He took up fox hunting, which he pursued enthusiastically for the next three decades. His professional role as a post-office surveyor brought him into contact with Irish people, and he found them pleasant company: "The Irish people did not murder me, nor did they even break my head. I soon found them to be good-humoured, clever—the working classes very much more intelligent than those of England—economical and hospitable." At the watering place of

Dún Laoghaire

Dún Laoghaire ( , ) is a suburban coastal town in Dublin in Ireland. It is the administrative centre of Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown.

The town was built following the 1816 legislation that allowed the building of a major port to serve Dubli ...

, Trollope met Rose Heseltine (1821–1917), the daughter of a Rotherham

Rotherham () is a large minster and market town in South Yorkshire, England. The town takes its name from the River Rother which then merges with the River Don. The River Don then flows through the town centre. It is the main settlement of ...

bank manager. They became engaged when he had been in Ireland for a year; because of Trollope's debts and her lack of a fortune, they were unable to marry until 1844. Their first son, Henry Merivale, was born in 1846, and the second, Frederick James Anthony, in 1847. Soon after their marriage, Trollope was transferred to another postal district in the south of Ireland, and the family moved to Clonmel.

Early works

Though Trollope had decided to become a novelist, he had accomplished very little writing during his first three years in Ireland. At the time of his marriage, he had only written the first of three volumes of his first novel, ''The Macdermots of Ballycloran

''The Macdermots of Ballycloran'' is a novel by Anthony Trollope. It was Trollope's first published novel, which he began in September 1843 and completed by June 1845. However, it was not published until 1847. The novel was "an abysmal failur ...

''. Within a year of his marriage, he finished that work.

Trollope began writing on the numerous long train trips around Ireland he had to take to carry out his postal duties. Setting very firm goals about how much he would write each day, he eventually became one of the most prolific writers of all time. He wrote his earliest novels while working as a Post Office inspector, occasionally dipping into the " lost-letter" box for ideas.

The Macdermots of Ballycloran

''The Macdermots of Ballycloran'' is a novel by Anthony Trollope. It was Trollope's first published novel, which he began in September 1843 and completed by June 1845. However, it was not published until 1847. The novel was "an abysmal failur ...

'', ''The Kellys and the O'Kellys

''The Kellys and the O'Kellys'' is a novel by Anthony Trollope

Anthony Trollope (; 24 April 1815 – 6 December 1882) was an English novelist and civil servant of the Victorian era. Among his best-known works is a series of novels collectiv ...

'', and '' Castle Richmond'', respectively). ''The Macdermots of Ballycloran'' was written while he was staying in the village of Drumsna

Drumsna ( which translates as ''the ridge of the swimming place'') is a village in County Leitrim, Ireland. It is situated 6 km east of Carrick-on-Shannon on the River Shannon and is located off the N4 National primary route which li ...

, County Leitrim

County Leitrim ( ; gle, Contae Liatroma) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Connacht and is part of the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the village of Leitrim. Leitrim County Council is the local authority for the ...

. ''The Kellys and the O'Kellys

''The Kellys and the O'Kellys'' is a novel by Anthony Trollope

Anthony Trollope (; 24 April 1815 – 6 December 1882) was an English novelist and civil servant of the Victorian era. Among his best-known works is a series of novels collectiv ...

'' (1848) is a humorous comparison of the romantic pursuits of the landed gentry (Francis O'Kelly, Lord Ballindine) and his Catholic tenant (Martin Kelly). Two short stories deal with Ireland ("The O'Conors of Castle Conor, County Mayo" and "Father Giles of Ballymoy"). Some critics argue that these works seek to unify an Irish and British identity, instead of viewing the two as distinct.Edwards p.3 Even as an Englishman in Ireland, Trollope was still able to attain what he saw as essential to being an "Irish writer": possessed, obsessed, and "mauled" by Ireland.

The reception of the Irish works left much to be desired. Henry Colburn

Henry Colburn (1784 – 16 August 1855) was a British publisher.

Life

Virtually nothing is known about Henry Colburn's parentage or early life, and there is uncertainty over his year of birth. He was well-educated and fluent in French and h ...

wrote to Trollope, "It is evident that readers do not like novels on Irish subjects as well as on others." In particular, magazines such as ''The New Monthly Magazine

''The New Monthly Magazine'' was a British monthly magazine published from 1814 to 1884. It was founded by Henry Colburn and published by him through to 1845.

History

Colburn and Frederic Shoberl established ''The New Monthly Magazine and Univ ...

'', which included reviews that attacked the Irish for their actions during the famine, were representative of the dismissal by English readers of any work written about the Irish.

Success as an author

In 1851, Trollope was sent to England, charged with investigating and reorganising rural mail delivery in south-western England and southWales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

. The two-year mission took him over much of Great Britain, often on horseback. Trollope describes this time as "two of the happiest years of my life".Trollope (1883).Chapter 5.

Retrieved 2 July 2010. In the course of it, he visited Salisbury Cathedral; and there, according to his autobiography, he conceived the plot of ''

The Warden

''The Warden'' is a novel by English author Anthony Trollope published by Longman in 1855. It is the first book in the '' Chronicles of Barsetshire'' series, followed by '' Barchester Towers''.

Synopsis

''The Warden'' concerns Mr Septimus Ha ...

'', which became the first of the six Barsetshire novels. His postal work delayed the beginning of writing for a year; the novel was published in 1855, in an edition of 1,000 copies, with Trollope receiving half of the profits: £9 8s. 8d. in 1855, and £10 15s. 1d. in 1856. Although the profits were not large, the book received notices in the press, and brought Trollope to the attention of the novel-reading public.

He immediately began work on '' Barchester Towers'', the second Barsetshire novel;Trollope (1883).

He immediately began work on '' Barchester Towers'', the second Barsetshire novel;Trollope (1883).Chapter 6.

Retrieved 2 July 2010. upon its publication in 1857,Trollope (1883).

Retrieved 2 July 2010. he received an advance payment of £100 (about £ in consumer pounds) against his share of the profits. Like ''The Warden'', ''Barchester Towers'' did not obtain large sales, but it helped to establish Trollope's reputation. In his autobiography, Trollope writes, "It achieved no great reputation, but it was one of the novels which novel readers were called upon to read." For the following novel, ''

The Three Clerks

''The Three Clerks'' (1857) is a novel by Anthony Trollope, set in the lower reaches of the Civil Service. It draws on Trollope's own experiences as a junior clerk in the General Post Office, and has been called the most autobiographical of Tr ...

'', he was able to sell the copyright for a lump sum of £250; he preferred this to waiting for a share of future profits.

Return to England

Although Trollope had been happy and comfortable in Ireland, he felt that as an author, he should live within easy reach of London. In 1859, he sought and obtained a position in the Post Office as Surveyor to the Eastern District, comprisingEssex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and Grea ...

, Suffolk, Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

, Cambridgeshire, Huntingdonshire

Huntingdonshire (; abbreviated Hunts) is a non-metropolitan district of Cambridgeshire and a historic county of England. The district council is based in Huntingdon. Other towns include St Ives, Godmanchester, St Neots and Ramsey. The popu ...

, and most of Hertfordshire.Trollope (1883).Chapter 8.

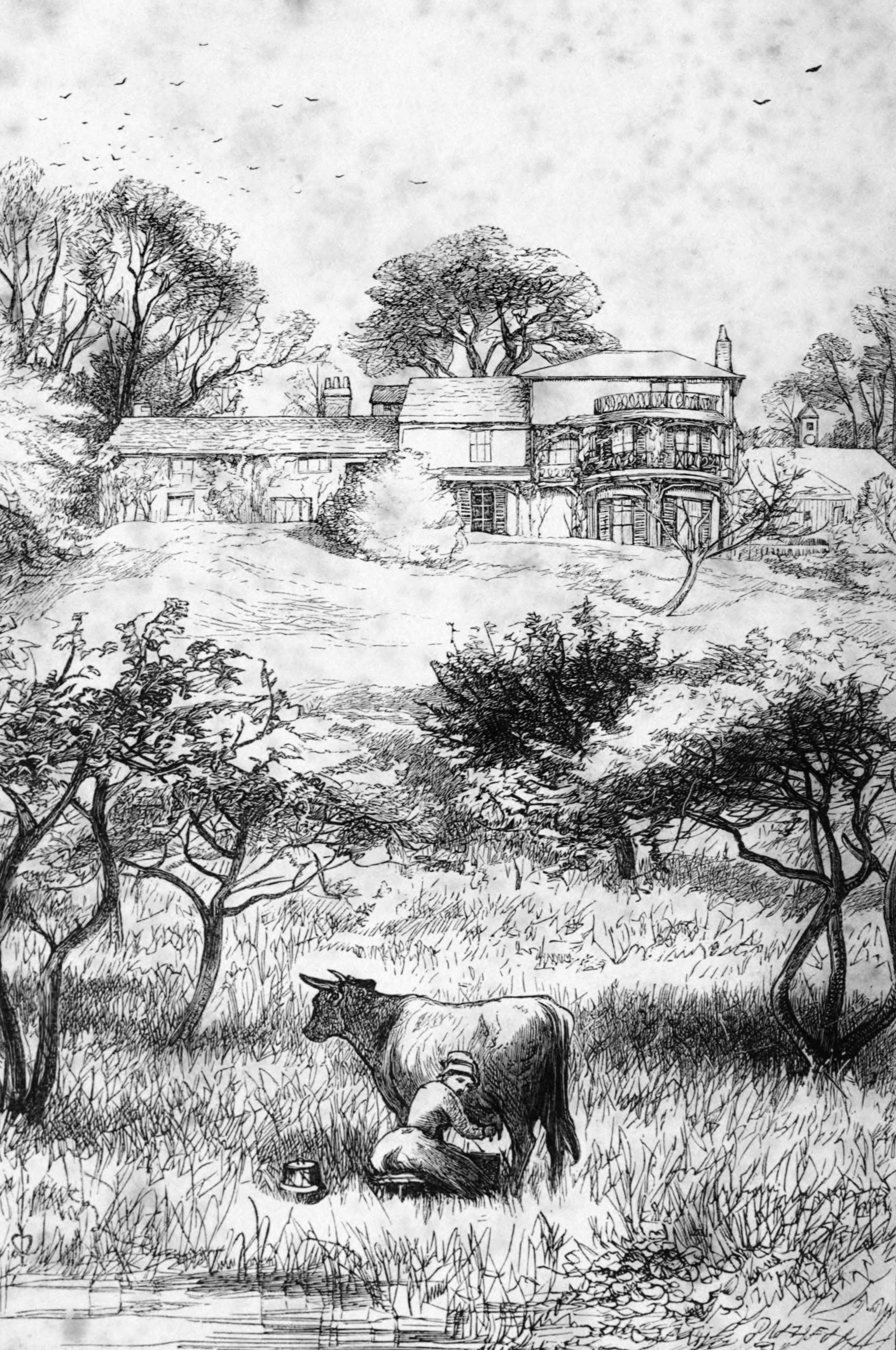

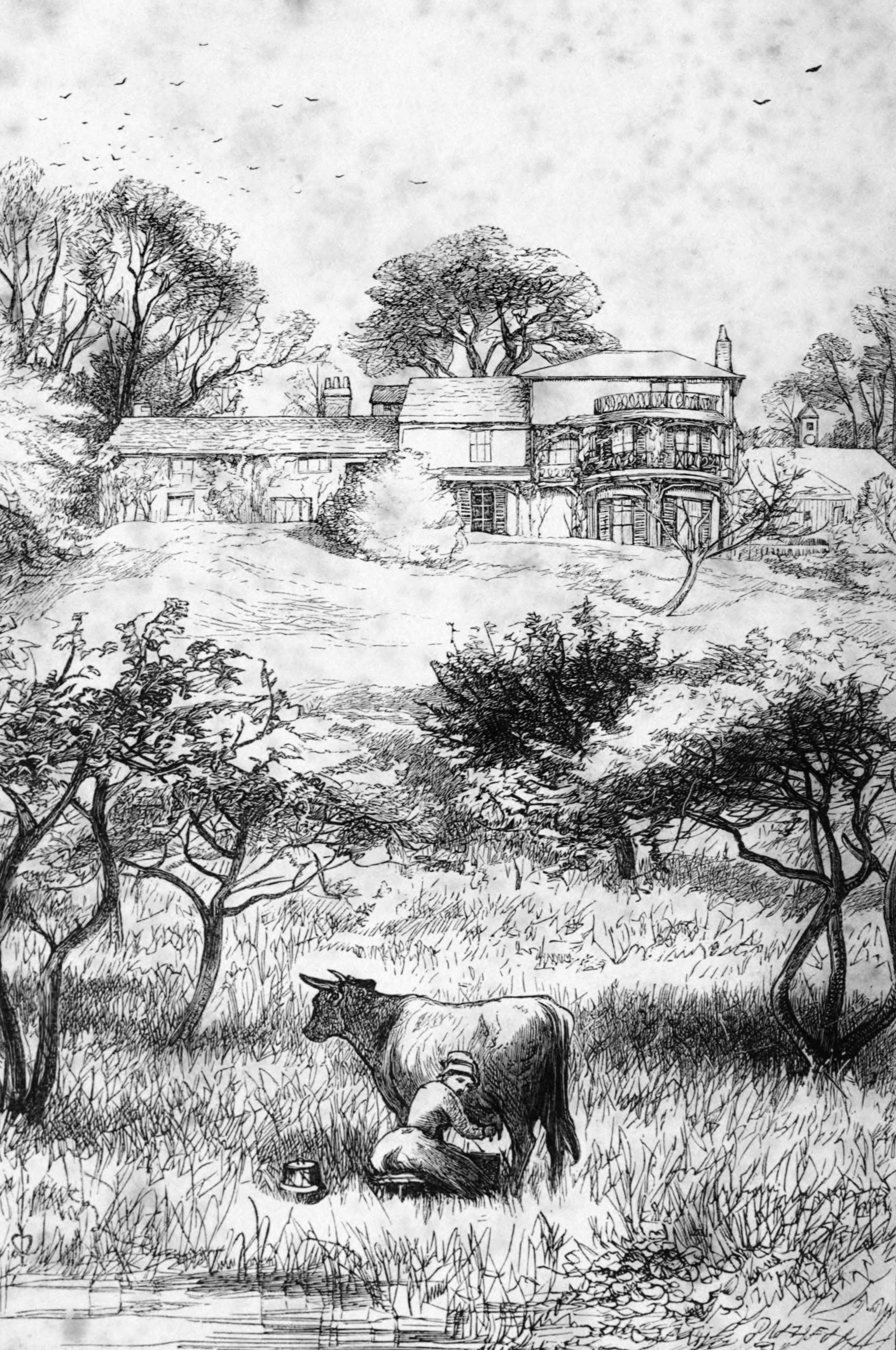

Retrieved 2 July 2010. Later in that year he moved to Waltham Cross, about from London in Hertfordshire, where he lived until 1871. In late 1859, Trollope learned of preparations for the release of the ''

Cornhill Magazine

''The Cornhill Magazine'' (1860–1975) was a monthly Victorian magazine and literary journal named after the street address of the founding publisher Smith, Elder & Co. at 65 Cornhill in London.Laurel Brake and Marysa Demoor, ''Dictiona ...

'', to be published by George Murray Smith

George Murray Smith (19 March 1824 – 6 April 1901) was a British publisher. He was the son of George Smith (1789–1846), who, with Alexander Elder (1790–1876), started the Victorian publishing firm of Smith, Elder & Co. in 1816. His br ...

and edited by William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray (; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was a British novelist, author and illustrator. He is known for his satirical works, particularly his 1848 novel ''Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portrait of British society, and t ...

. He wrote to the latter, offering to provide short stories for the new magazine. Thackeray and Smith both responded: the former urging Trollope to contribute, the latter offering £1,000 for a novel, provided that a substantial part of it could be available to the printer within six weeks. Trollope offered Smith '' Castle Richmond'', which he was then writing; but Smith declined to accept an Irish story, and suggested a novel dealing with English clerical life as had ''Barchester Towers''. Trollope then devised the plot of '' Framley Parsonage'', setting it near Barchester so that he could make use of characters from the Barsetshire novels.Sadleir, Michael (1927). ''Trollope: A Commentary''. Farrar, Straus and Company.

''Framley Parsonage'' proved enormously popular, establishing Trollope's reputation with the novel-reading public and amply justifying the high price that Smith had paid for it. The early connection to ''Cornhill'' also brought Trollope into the London circle of artists, writers, and intellectuals, not least among whom were Smith and Thackeray.

By the mid-1860s, Trollope had reached a fairly senior position within the Post Office hierarchy, despite ongoing differences with Rowland Hill

Sir Rowland Hill, KCB, FRS (3 December 1795 – 27 August 1879) was an English teacher, inventor and social reformer. He campaigned for a comprehensive reform of the postal system, based on the concept of Uniform Penny Post and his soluti ...

, who was at that time Chief Secretary to the Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having a government official responsib ...

. Postal history credits Trollope with introducing the pillar box

A pillar box is a type of free-standing post box. They are found in the United Kingdom and British overseas territories, and, less commonly, in many members of the Commonwealth of Nations such as Cyprus, India, Gibraltar, Hong Kong, Malta, New Z ...

(the ubiquitous mail-box) in the United Kingdom. He was earning a substantial income from his novels. He had overcome the awkwardness of his youth, made good friends in literary circles, and hunted enthusiastically. In 1865, Trollope was among the founders of the liberal Fortnightly Review

''The Fortnightly Review'' was one of the most prominent and influential magazines in nineteenth-century England. It was founded in 1865 by Anthony Trollope, Frederic Harrison, Edward Spencer Beesly, and six others with an investment of £9,000 ...

.

When Hill left the Post Office in 1864, Trollope's brother-in-law, John Tilley, who was then Under-Secretary to the Postmaster General, was appointed to the vacant position. Trollope applied for Tilley's old post, but was passed over in favour of a subordinate, Frank Ives Scudamore. In the autumn of 1867, Trollope resigned his position at the Post Office, having by that time saved enough to generate an income equal to the pension he would lose by leaving before the age of 60.Trollope (1883)Chapter 15.

Retrieved 2 July 2010.

Beverley campaign

Trollope had long dreamt of taking a seat in theHouse of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

.Trollope (1883)chapter 16.

Retrieved 21 May 2010. As a civil servant, however, he was ineligible for such a position. His resignation from the Post Office removed this disability, and he almost immediately began seeking a seat for which he might stand.Super, R. H. (1988).

''The Chronicler of Barsetshire''.

University of Michigan Press.

pp. 251–5.

Retrieved 19 May 2010. In 1868, he agreed to stand as a

Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

candidate in the borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

In the Middle A ...

of Beverley

Beverley is a market and minster town and a civil parish in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England, of which it is the county town. The town centre is located south-east of York's centre and north-west of City of Hull.

The town is known fo ...

, in the East Riding of Yorkshire

The East Riding of Yorkshire, or simply East Riding or East Yorkshire, is a ceremonial county and unitary authority area in the Yorkshire and the Humber region of England. It borders North Yorkshire to the north and west, South Yorkshire to t ...

.

Party leaders apparently took advantage of Trollope's eagerness to stand, and of his willingness to spend money on a campaign. Beverley had a long history of vote-buying and of intimidation by employers and others. Every election since 1857 had been followed by a petition alleging corruption, and it was estimated that 300 of the 1,100 voters in 1868 would sell their votes.Modern Beverley: Political and Social History, 1835–1918.Retrieved 20 May 2010.

Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

candidates an opportunity to display overt corruption, which could then be used to disqualify them.

Trollope described his period of campaigning in Beverley as "the most wretched fortnight of my manhood".

He spent a total of £400 on his campaign. The election was held on 17 November 1868; the novelist finished last of four candidates, with the victory going to the two Conservatives. A petition was filed, and a Royal Commission investigated the circumstances of the election; its findings of extensive and widespread corruption drew nationwide attention, and led to the disfranchisement of the borough in 1870. The fictional Percycross election in ''Ralph the Heir

''Ralph the Heir'' is a novel by Anthony Trollope, originally published in 1871. Although Trollope described it as "one of the worst novels I have written",Trollope, Anthony (1883).''An Autobiography'', chapter 19. Retrieved 2010-05-19.

it was w ...

'' and Tankerville election in Phineas Redux is closely based on the Beverley campaign.

Later years

After the defeat at Beverley, Trollope concentrated entirely on his literary career. While continuing to produce novels rapidly, he also edited the ''St Paul's Magazine'', which published several of his novels in serial form. "Between 1859 and 1875, Trollope visited the United States five times. Among American literary men he developed a wide acquaintance, which included Lowell,Holmes

Holmes may refer to:

Name

* Holmes (surname)

* Holmes (given name)

* Baron Holmes, noble title created twice in the Peerage of Ireland

* Chris Holmes, Baron Holmes of Richmond (born 1971), British former swimmer and life peer

Places

In the Uni ...

, Emerson, Agassiz, Hawthorne

Hawthorne often refers to the American writer Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Hawthorne may also refer to:

Places

Australia

*Hawthorne, Queensland, a suburb of Brisbane

Canada

* Hawthorne Village, Ontario, a suburb of Milton, Ontario

United States

* Hawt ...

, Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include "Paul Revere's Ride", ''The Song of Hiawatha'', and ''Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely transl ...

, Bret Harte

Bret Harte (; born Francis Brett Hart; August 25, 1836 – May 5, 1902) was an American short story writer and poet best remembered for short fiction featuring miners, gamblers, and other romantic figures of the California Gold Rush.

In a caree ...

, Artemus Ward, Joaquin Miller

Cincinnatus Heine Miller (; September 8, 1837 – February 17, 1913), better known by his pen name Joaquin Miller (), was an American poet, author, and frontiersman. He is nicknamed the "Poet of the Sierras" after the Sierra Nevada, about which h ...

, Mark Twain, Henry James

Henry James ( – ) was an American-British author. He is regarded as a key transitional figure between literary realism and literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest novelists in the English language. He was the ...

, William Dean Howells

William Dean Howells (; March 1, 1837 – May 11, 1920) was an American realist novelist, literary critic, and playwright, nicknamed "The Dean of American Letters". He was particularly known for his tenure as editor of ''The Atlantic Monthly'', ...

, James T. Fields, Charles Norton, John Lothrop Motley

John Lothrop Motley (April 15, 1814 – May 29, 1877) was an American author and diplomat. As a popular historian, he is best known for his works on the Netherlands, the three volume work ''The Rise of the Dutch Republic'' and four volume ''His ...

, and Richard Henry Dana, Jr."

Trollope wrote a travel book focusing on his experiences in the US during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

titled ''North America'' (1862). Aware that his mother had published a harshly anti-American

Anti-Americanism (also called anti-American sentiment) is prejudice, fear, or hatred of the United States, its government, its foreign policy, or Americans in general.

Political scientist Brendon O'Connor at the United States Studies Centr ...

travel book about the U.S. (titled the ''Domestic Manners of the Americans

''Domestic Manners of the Americans'' is a two-volume travel book by Frances Milton Trollope, published in 1832, which follows her travels through America and her residence in Cincinnati, at the time still a frontier town.

Context

Frances Trol ...

'') and feeling markedly more sympathetic to the United States, Trollope resolved to write a work which would "add to the good feeling which should exist between two nations which ought to love each other." During his time in America, Trollope remained a steadfast supporter of the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

, being a committed abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

who was opposed to the system of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

as it existed in the South.

In 1871, Trollope made his first trip to Australia, arriving in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

on 28 July 1871 on the SS ''Great Britain'', with his wife and their cook. The trip was made to visit their younger son, Frederick, who was a sheep farmer near Grenfell, New South Wales

Grenfell is a town in Weddin Shire in the Central West (New South Wales), Central West of New South Wales, Australia. It is west of Sydney. It is close to Forbes, New South Wales, Forbes, Cowra, New South Wales, Cowra and Young, New South Wal ...

.Starck, Nigel (2008) "Anthony Trollope's travels and travails in 1871 Australia", ''National Library of Australia News'', XIX (1), p. 19 He wrote his novel '' Lady Anna'' during the voyage. In Australia, he spent a year and two days "descending mines, mixing with shearers and rouseabouts, riding his horse into the loneliness of the bush, touring lunatic asylums, and exploring coast and plain by steamer and stagecoach".Starck, p. 20 He visited the penal colony of Port Arthur and its cemetery, Isle of the Dead. Despite this, the Australian press was uneasy, fearing he would misrepresent Australia in his writings. This fear was based on rather negative writings about America by his mother, Fanny, and by Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

. On his return, Trollope published a book, ''Australia and New Zealand'' (1873). It contained both positive and negative comments. On the positive side, it found a comparative absence of class consciousness, and praised aspects of Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth is ...

, Melbourne, Hobart

Hobart ( ; Nuennonne/Palawa kani: ''nipaluna'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian island state of Tasmania. Home to almost half of all Tasmanians, it is the least-populated Australian state capital city, and second-small ...

and Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

. However, he was negative about Adelaide's river, the towns of Bendigo and Ballarat

Ballarat ( ) is a city in the Central Highlands (Victoria), Central Highlands of Victoria (Australia), Victoria, Australia. At the 2021 Census, Ballarat had a population of 116,201, making it the third largest city in Victoria. Estimated resid ...

, and the Aboriginal population. What most angered the Australian papers, though, were his comments "accusing Australians of being braggarts".

Trollope returned to Australia in 1875 to help his son close down his failed farming business. He found that the resentment created by his accusations of bragging remained. Even when he died in 1882, Australian papers still "smouldered", referring yet again to these accusations, and refusing to fully praise or recognize his achievements.Starck, p. 21

In the late 1870's, Trollope furthered his travel writing career by visiting

Trollope returned to Australia in 1875 to help his son close down his failed farming business. He found that the resentment created by his accusations of bragging remained. Even when he died in 1882, Australian papers still "smouldered", referring yet again to these accusations, and refusing to fully praise or recognize his achievements.Starck, p. 21

In the late 1870's, Trollope furthered his travel writing career by visiting southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost subregion of the African continent, south of the Congo and Tanzania. The physical location is the large part of Africa to the south of the extensive Congo River basin. Southern Africa is home to a number of ...

, including the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when i ...

and the Boer Republics of the Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

and the Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

. Admitting that he initially assumed that the Afrikaners

Afrikaners () are a South African ethnic group descended from Free Burghers, predominantly Dutch settlers first arriving at the Cape of Good Hope in the 17th and 18th centuries.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: ...

had "retrograded from civilization, and had become savage, barbarous, and unkindly", Trollope wrote at length on Boer cultural habits, claiming that the "roughness... Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

n simplicity and the dirtiness of the Boer’s way of life erelyresulted from his preference for living in rural isolation, far from any town." In the completed work, which Trollope simply titled ''South Africa'' (1877), he described the mining town of Kimberly

Kimberly or Kimberley may refer to:

Places and historical events

Australia

* Kimberley (Western Australia)

** Roman Catholic Diocese of Kimberley

* Kimberley Warm Springs, Tasmania

* Kimberley, Tasmania a small town

* County of Kimberley, a c ...

as being "one of the most interesting places on the face of the earth."

In 1880, Trollope moved to the village of South Harting

South Harting is a village within Harting civil parish in the Chichester District, Chichester district of West Sussex, England.OS Explorer map 120: Chichester, South Harting and Selsey Scale: 1:25 000. Publisher:Ordnance Survey – Southampton B2 ...

in West Sussex. He spent some time in Ireland in the early 1880s researching his last, unfinished, novel, ''The Landleaguers''. It is said that he was extremely distressed by the violence of the Land War

The Land War ( ga, Cogadh na Talún) was a period of agrarian agitation in rural Ireland (then wholly part of the United Kingdom) that began in 1879. It may refer specifically to the first and most intense period of agitation between 1879 and 18 ...

.

Death

Trollope died inMarylebone

Marylebone (usually , also , ) is a district in the West End of London, in the City of Westminster. Oxford Street, Europe's busiest shopping street, forms its southern boundary.

An ancient parish and latterly a metropolitan borough, it me ...

, London, in 1882 and is buried in Kensal Green Cemetery

Kensal Green Cemetery is a cemetery in the Kensal Green area of Queens Park in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in London, England. Inspired by Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, it was founded by the barrister George Frederick ...

, near the grave of his contemporary, Wilkie Collins

William Wilkie Collins (8 January 1824 – 23 September 1889) was an English novelist and playwright known especially for '' The Woman in White'' (1859), a mystery novel and early "sensation novel", and for '' The Moonstone'' (1868), which has b ...

.

Works and reputation

Trollope's first major success came with ''The Warden

''The Warden'' is a novel by English author Anthony Trollope published by Longman in 1855. It is the first book in the '' Chronicles of Barsetshire'' series, followed by '' Barchester Towers''.

Synopsis

''The Warden'' concerns Mr Septimus Ha ...

'' (1855)—the first of six novels set in the fictional county of "Barsetshire" (often collectively referred to as the '' Chronicles of Barsetshire''), dealing primarily with the clergy and landed gentry. '' Barchester Towers'' (1857) has probably become the best-known of these. Trollope's other major series, the Palliser novels

The Palliser novels are novels written in series by Anthony Trollope. They were more commonly known as the Parliamentary novels prior to their 1974 television dramatisation by the BBC broadcast as ''The Pallisers''. Marketed as "polite literat ...

, which overlap with the Barsetshire novels, concerned itself with politics, with the wealthy, industrious Plantagenet Palliser

The Palliser novels are novels written in series by Anthony Trollope. They were more commonly known as the Parliamentary novels prior to their 1974 television dramatisation by the BBC broadcast as ''The Pallisers''. Marketed as "polite literat ...

(later Duke of Omnium) and his delightfully spontaneous, even richer wife Lady Glencora featured prominently, though, as with the Barsetshire series, many other well-developed characters populated each novel and in one, ''The Eustace Diamonds

''The Eustace Diamonds'' is a novel by Anthony Trollope, first published in 1871 as a serial in the ''Fortnightly Review''. It is the third of the " Palliser" series of novels.

Plot summary

In this novel, the characters of Plantagenet Palliser ...

'', the Pallisers play only a small role.

Trollope's popularity and critical success diminished in his later years, but he continued to write prolifically, and some of his later novels have acquired a good reputation. In particular, critics who concur that the book was not popular when published, generally acknowledge the sweeping satire ''

Trollope's popularity and critical success diminished in his later years, but he continued to write prolifically, and some of his later novels have acquired a good reputation. In particular, critics who concur that the book was not popular when published, generally acknowledge the sweeping satire ''The Way We Live Now

''The Way We Live Now'' is a satirical novel by Anthony Trollope, published in London in 1875 after first appearing in serialised form. It is one of the last significant Victorian novels to have been published in monthly parts.

The novel is ...

'' (1875) as his masterpiece. In all, Trollope wrote 47 novels, 42 short stories, and five travel books, as well as nonfiction books titled ''Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray (; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was a British novelist, author and illustrator. He is known for his satirical works, particularly his 1848 novel ''Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portrait of British society, and th ...

'' (1879) and ''Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865) was a British statesman who was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century. Palmerston dominated British foreign policy during the period ...

'' (1882).

After his death, Trollope's ''An Autobiography'' appeared and was a bestseller in London. Trollope's downfall in the eyes of the critics stemmed largely from this volume. Even during his writing career, reviewers tended increasingly to shake their heads over his prodigious output, but when Trollope revealed that he strictly adhered to a daily writing quota, and admitted that he wrote for money, he confirmed his critics' worst fears. Writers were expected to wait for inspiration, not to follow a schedule.

Julian Hawthorne

Julian Hawthorne (June 22, 1846 – July 14, 1934) was an American writer and journalist, the son of novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne and Sophia Peabody. He wrote numerous poems, novels, short stories, mysteries and detective fiction, essays, t ...

, an American writer, critic and friend of Trollope, while praising him as a man, calling him "a credit to England and to human nature, and ... eservingto be numbered among the darlings of mankind", also said that "he has done great harm to English fictitious literature by his novels".

Henry James

Henry James ( – ) was an American-British author. He is regarded as a key transitional figure between literary realism and literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest novelists in the English language. He was the ...

also expressed mixed opinions of Trollope. The young James wrote some scathing reviews of Trollope's novels (''The Belton Estate'', for instance, he called "a stupid book, without a single thought or idea in it ... a sort of mental pabulum

{{Wiktionary

* pabulum: word; "denoting material for intellectual nourishment; food for thought;"

* Pablum: product; infant cereal from Mead Johnson

Mead Johnson & Company, LLC is an American company that is a leading manufacturer of infant form ...

"). He also made it clear that he disliked Trollope's narrative method; Trollope's cheerful interpolations into his novels about how his storylines could take any twist their author wanted did not appeal to James's sense of artistic integrity. However, James thoroughly appreciated Trollope's attention to realistic detail, as he wrote in an essay shortly after the novelist's death:

His rollope'sgreat, his inestimable merit was a complete appreciation of the usual. ... ''felt'' all daily and immediate things as well as saw them; felt them in a simple, direct, salubrious way, with their sadness, their gladness, their charm, their comicality, all their obvious and measurable meanings. ... Trollope will remain one of the most trustworthy, though not one of the most eloquent, of the writers who have helped the heart of man to know itself. ... A race is fortunate when it has a good deal of the sort of imagination—of imaginative feeling—that had fallen to the share of Anthony Trollope; and in this possession our English race is not poor.Writers such as

William Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray (; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was a British novelist, author and illustrator. He is known for his satirical works, particularly his 1848 novel ''Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portrait of British society, and th ...

, George Eliot

Mary Ann Evans (22 November 1819 – 22 December 1880; alternatively Mary Anne or Marian), known by her pen name George Eliot, was an English novelist, poet, journalist, translator, and one of the leading writers of the Victorian era. She wrot ...

and Wilkie Collins

William Wilkie Collins (8 January 1824 – 23 September 1889) was an English novelist and playwright known especially for '' The Woman in White'' (1859), a mystery novel and early "sensation novel", and for '' The Moonstone'' (1868), which has b ...

admired and befriended Trollope, and Eliot noted that she could not have embarked on so ambitious a project as ''Middlemarch

''Middlemarch, A Study of Provincial Life'' is a novel by the English author Mary Anne Evans, who wrote as George Eliot. It first appeared in eight installments (volumes) in 1871 and 1872. Set in Middlemarch, a fictional English Midland town, ...

'' without the precedent set by Trollope in his own novels of the fictional—yet thoroughly alive—county of Barsetshire. Other contemporaries of Trollope praised his understanding of the quotidian world of institutions, official life, and daily business; he is one of the few novelists who find the office a creative environment. W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry was noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in ...

wrote of Trollope: "Of all novelists in any country, Trollope best understands the role of money. Compared with him, even Balzac is too romantic."

As trends in the world of the novel moved increasingly towards subjectivity and artistic experimentation, Trollope's standing with critics suffered. But Lord David Cecil

Lord Edward Christian David Gascoyne-Cecil, CH (9 April 1902 – 1 January 1986) was a British biographer, historian, and scholar. He held the style of "Lord" by courtesy, as a younger son of a marquess.

Early life and studies

David Cecil was ...

noted in 1934 that "Trollope is still very much alive ... and among fastidious readers." He noted that Trollope was "conspicuously free from the most characteristic Victorian faults". In the 1940s, Trollopians made further attempts to resurrect his reputation; he enjoyed a critical renaissance in the 1960s, and again in the 1990s. Some critics today have a particular interest in Trollope's portrayal of women—he caused remark even in his own day for his deep insight and sensitivity to the inner conflicts caused by the position of women in Victorian society.

Recently, interest in Trollope has increased. A Trollope Society flourishes in the United Kingdom, as does its sister society in the United States. In 2011, the University of Kansas

The University of Kansas (KU) is a public research university with its main campus in Lawrence, Kansas, United States, and several satellite campuses, research and educational centers, medical centers, and classes across the state of Kansas. Tw ...

's Department of English, in collaboration with the Hall Center for the Humanities and in partnership with ''The Fortnightly Review

''The Fortnightly Review'' was one of the most prominent and influential magazines in nineteenth-century England. It was founded in 1865 by Anthony Trollope, Frederic Harrison, Edward Spencer Beesly, and six others with an investment of £9,00 ...

'', began awarding an annual Trollope Prize. The Prize was established to focus attention on Trollope's work and career.

Notable fans have included Alec Guinness, who never travelled without a Trollope novel; the former British prime ministers Harold Macmillan and Sir John Major; the first Canadian prime minister, John A. Macdonald

Sir John Alexander Macdonald (January 10 or 11, 1815 – June 6, 1891) was the first prime minister of Canada, serving from 1867 to 1873 and from 1878 to 1891. The dominant figure of Canadian Confederation, he had a political career that sp ...

; the economist John Kenneth Galbraith

John Kenneth Galbraith (October 15, 1908 – April 29, 2006), also known as Ken Galbraith, was a Canadian-American economist, diplomat, public official, and intellectual. His books on economic topics were bestsellers from the 1950s through t ...

; the merchant banker Siegmund Warburg

Sir Siegmund George Warburg (30 September 1902 – 18 October 1982) was a German-born English banker. He was a member of the prominent Warburg family. He played a prominent role in the development of merchant banking.Lord Denning

Alfred Thompson "Tom" Denning, Baron Denning (23 January 1899 – 5 March 1999) was an English lawyer and judge. He was called to the bar of England and Wales in 1923 and became a King's Counsel in 1938. Denning became a judge in 1944 wh ...

; the American novelists Sue Grafton, Dominick Dunne

Dominick John Dunne (October 29, 1925 – August 26, 2009) was an American writer, investigative journalist, and producer. He began his career in film and television as a producer of the pioneering gay film '' The Boys in the Band'' (1970) and ...

, and Timothy Hallinan; the poet Edward Fitzgerald; the artist Edward Gorey

Edward St. John Gorey (February 22, 1925 – April 15, 2000) was an American writer, Tony Award-winning costume designer, and artist, noted for his own illustrated books as well as cover art and illustration for books by other writers. Hi ...

, who kept a complete set of his books; the American author Robert Caro

Robert Allan Caro (born October 30, 1935) is an American journalist and author known for his biographies of United States political figures Robert Moses and Lyndon B. Johnson.

After working for many years as a reporter, Caro wrote '' The Power ...

; the playwright David Mamet

David Alan Mamet (; born November 30, 1947) is an American playwright, filmmaker, and author. He won a Pulitzer Prize and received Tony nominations for his plays ''Glengarry Glen Ross'' (1984) and '' Speed-the-Plow'' (1988). He first gained cri ...

; the soap opera writer Harding Lemay

Harding Lemay (March 16, 1922 – May 26, 2018), also known as Pete Lemay, was an American screenwriter and playwright. He was best known for his stint as head writer of the soap opera '' Another World''.

Career

Lemay was head writer of the s ...

; the screenwriter and novelist Julian Fellowes

Julian Alexander Kitchener-Fellowes, Baron Fellowes of West Stafford, (born 17 August 1949) is an English actor, novelist, film director and screenwriter, and a Conservative peer of the House of Lords.

He is primarily known as the author of se ...

; liberal political philosopher Anthony de Jasay; and theologian Stanley Hauerwas

Stanley Martin Hauerwas (born July 24, 1940) is an American theologian, ethicist, and public intellectual. Hauerwas was a longtime professor at Duke University, serving as the Gilbert T. Rowe Professor of Theological Ethics at Duke Divinity Schoo ...

.

Bibliography

*Anthony Trollope bibliography

This is a bibliography of the works of Anthony Trollope.

Novels

Single novels

Novel series

Chronicles of Barsetshire

Palliser novels

Irish novels

Short stories

* ''Tales of All Countries (Trollope), Tales of All Countries, 1st Series ...

Notes

References

Further reading

* Olmsted, Charles and Jeffrey Welch (1978). ''The Reputation of Trollope: An annotated Bibliography'', Garland Publishing. * Sadleir, Michael (1928). ''Trollope: A Bibliography'', Wm. Dawson & Sons. Literary allusions in Trollope's novels have been identified and traced by Professor James A. Means, in two articles that appeared in ''The Victorian Newsletter'' (vols. 78 and 82) in 1990 and 1992 respectively. * *Briggs, Asa

Asa Briggs, Baron Briggs (7 May 1921 – 15 March 2016) was an English historian. He was a leading specialist on the Victorian era, and the foremost historian of broadcasting in Britain. Briggs achieved international recognition during his lon ...

, "Trollope, Bagehot, and the English Constitution," in Briggs, ''Victorian People'' (1955) pp. 87–115online

* Cockshut, O. J. (1955). ''Anthony Trollope: A Critical Study'', London: Collins. * Escott, T. H. S. (1913)

''Anthony Trollope, his Work, Associates and Literary Originals''

John Lane: The Bodley Head. * Gerould, Winifred and James (1948). ''A Guide to Trollope'', Princeton University Press. * Glendinning, Victoria (1992). ''Anthony Trollope'', Alfred A. Knopf. * * Hall, N. John (1991). ''Trollope: A Biography'', Clarendon Press. * Kincaid, James R. (1977). ''The Novels of Anthony Trollope'', Oxford: Clarendon Press. * MacDonald, Susan (1987). ''Anthony Trollope'', Twayne Publishers. * Mullen, Richard (1990). ''Anthony Trollope: A Victorian in his World'', Savannah: Frederic C. Beil. * Polhemus, Robert M. (1966). ''The Changing World of Anthony Trollope'', University of California Press. * Pollard, Arthur (1978). ''Anthony Trollope'', Routledge & Kegan Paul, Limited. * Pope-Hennessy, James (1971). ''Anthony Trollope'', Jonathan Cape. * * Terry, R.C., ed. (1999). ''Oxford Reader's Companion to Trollope'', Oxford University Press. * Smalley, Donald (1969). ''Anthony Trollope: The Critical Heritage'', Routledge. * Walpole, Hugh (1928)

''Anthony Trollope''

New York: The Macmillan Company.

External links

;Digital collections * * * * *Anthony Trollope

—

Google Books

Google Books (previously known as Google Book Search, Google Print, and by its code-name Project Ocean) is a service from Google Inc. that searches the full text of books and magazines that Google has scanned, converted to text using optical c ...

;Physical collections

Anthony Trollope

at the British Library * Anthony Trollope Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Collection of portraits of Trollope at the National Portrait Gallery, London

;Other links

Trollope Society website

Classical references

in the Barsetshire series of novels, researched by students from

Hendrix College

Hendrix College is a private liberal arts college in Conway, Arkansas. Approximately 1,000 students are enrolled, mostly undergraduates. While affiliated with the United Methodist Church, the college offers a secular curriculum and has a student ...

.

Vanity Fair – Mrs. Trollope's America

The Trollope Prize

at the University of Kansas.

The Fortnightly Review Prospectus

by Anthony Trollope {{DEFAULTSORT:Trollope, Anthony 1815 births 1882 deaths 19th-century British dramatists and playwrights 19th-century British non-fiction writers 19th-century British novelists 19th-century British short story writers 19th-century English dramatists and playwrights 19th-century English non-fiction writers 19th-century English novelists 19th-century essayists British anti-poverty advocates British anti-capitalists British autobiographers British biographers British humorists British literary critics British male dramatists and playwrights British male essayists British male novelists British male short story writers British satirists British short story writers British travel writers Burials at Kensal Green Cemetery Civil servants in the General Post Office Cultural critics English essayists Freemasons of the United Grand Lodge of England Literacy and society theorists Literary theorists People educated at Harrow School People educated at Winchester College People from South Harting British social commentators Social critics Victorian novelists Writers about activism and social change Writers from London