Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern pr ...

from 1997 to 2007 and

Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as

Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

from 1994 to 1997, and had served in various

shadow cabinet posts from 1987 to 1994. Blair was the

Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

(MP) for

Sedgefield

Sedgefield is a market town and civil parish in County Durham, England. It had a population of 5,211 as at the 2011 census. It has the only operating racecourse in County Durham.

History Roman

A Roman 'ladder settlement' was discovered by C ...

from 1983 to 2007. He is the second longest serving prime minister in modern history after

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. S ...

, and is the longest serving Labour politician to have held the office.

Blair attended the independent school

Fettes College

Fettes College () is a co-educational independent boarding and day school in Edinburgh, Scotland, with over two-thirds of its pupils in residence on campus. The school was originally a boarding school for boys only and became co-ed in 1983. In ...

, and studied law at

St John's College, Oxford

St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. Founded as a men's college in 1555, it has been coeducational since 1979.Communication from Michael Riordan, college archivist Its founder, Sir Thomas White, intended to pro ...

, where he became a barrister. He became involved in

Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

politics and was elected to the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

in 1983 for the Sedgefield constituency in

County Durham

County Durham ( ), officially simply Durham,UK General Acts 1997 c. 23Lieutenancies Act 1997 Schedule 1(3). From legislation.gov.uk, retrieved 6 April 2022. is a ceremonial county in North East England.North East Assembly �About North East E ...

. As a

backbencher

In Westminster and other parliamentary systems, a backbencher is a member of parliament (MP) or a legislator who occupies no governmental office and is not a frontbench spokesperson in the Opposition, being instead simply a member of the " ...

, Blair supported moving the party to the

political centre of British politics. He was appointed to

Neil Kinnock

Neil Gordon Kinnock, Baron Kinnock (born 28 March 1942) is a British former politician. As a member of the Labour Party, he served as a Member of Parliament from 1970 until 1995, first for Bedwellty and then for Islwyn. He was the Leader of ...

's

shadow cabinet in 1988 and was appointed

shadow home secretary

In British politics, the Shadow Home Secretary (formally known as the Shadow Secretary of State for the Home Department) is the person within the shadow cabinet who shadows the Home Secretary; this effectively means scrutinising government polic ...

by

John Smith in 1992. Following the death of Smith in 1994, Blair won the

1994 Labour Party leadership election

A Labour Party leadership election was held on 21 July 1994 after the sudden death of the incumbent leader, John Smith, on 12 May. Tony Blair won the leadership and became Prime Minister after winning the 1997 general election.

The election ...

to succeed him. His tenure as leader began with a historic rebranding of the party, who began to use the campaign label

New Labour

New Labour was a period in the history of the British Labour Party from the mid to late 1990s until 2010 under the leadership of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. The name dates from a conference slogan first used by the party in 1994, later seen ...

. The name dates from a conference slogan first used by the party in 1994, later seen in a draft

manifesto

A manifesto is a published declaration of the intentions, motives, or views of the issuer, be it an individual, group, political party or government. A manifesto usually accepts a previously published opinion or public consensus or promotes a ...

which was published in 1996 and titled ''

New Labour, New Life for Britain

''New Labour, New Life for Britain'' was a political manifesto published in 1996 by the British Labour Party. The party had recently rebranded itself as New Labour under Tony Blair. The manifesto set out the party's new "Third Way" centrist approa ...

,'' and was presented as the brand of a newly reformed party.

Blair was appointed prime minister after Labour won the

1997 general election, its largest

landslide

Landslides, also known as landslips, are several forms of mass wasting that may include a wide range of ground movements, such as rockfalls, deep-seated grade (slope), slope failures, mudflows, and debris flows. Landslides occur in a variety of ...

general election victory in history, becoming the youngest prime minister of the 20th century. During

his first term, Blair enacted constitutional reforms, and significantly increased

public spending

Government spending or expenditure includes all government consumption, investment, and transfer payments. In national income accounting, the acquisition by governments of goods and services for current use, to directly satisfy the individual o ...

on healthcare and education, while also introducing controversial market-based reforms in these areas. In addition, Blair saw the introduction of a

minimum wage

A minimum wage is the lowest remuneration that employers can legally pay their employees—the price floor below which employees may not sell their labor. Most countries had introduced minimum wage legislation by the end of the 20th century. Bec ...

, tuition fees for higher education,

constitutional reform

A constitutional amendment is a modification of the constitution of a polity, organization or other type of entity. Amendments are often interwoven into the relevant sections of an existing constitution, directly altering the text. Conversely, t ...

such as

devolution in Scotland and Wales and progress in the

Northern Ireland peace process

The Northern Ireland peace process includes the events leading up to the 1994 Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) ceasefire, the end of most of the violence of the Troubles, the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, and subsequent political developm ...

. On foreign policy, Blair oversaw British interventions in

Kosovo

Kosovo ( sq, Kosova or ; sr-Cyrl, Косово ), officially the Republic of Kosovo ( sq, Republika e Kosovës, links=no; sr, Република Косово, Republika Kosovo, links=no), is a partially recognised state in Southeast Euro ...

in 1999 and

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierra ...

in 2000, which were generally perceived as successful.

Blair won another landslide re-election in

2001 United Kingdom general election, 2001. Three months into

his second term, Blair's premiership was shaped by the

September 11 terrorist attacks in the United States, resulting in the start of the

war on terror

The war on terror, officially the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT), is an ongoing international Counterterrorism, counterterrorism military campaign initiated by the United States following the September 11 attacks. The main targets of the campa ...

. Blair supported the

foreign policy of the George W. Bush administration

The main event by far shaping the foreign policy of the United States during the presidency of George W. Bush (2001–2009) was the 9/11 terrorist attacks against the United States on September 11, 2001, and the subsequent war on terror. There ...

by ensuring that the

British Armed Forces

The British Armed Forces, also known as His Majesty's Armed Forces, are the military forces responsible for the defence of the United Kingdom, its Overseas Territories and the Crown Dependencies. They also promote the UK's wider interests, s ...

participated in the

War in Afghanistan

War in Afghanistan, Afghan war, or Afghan civil war may refer to:

*Conquest of Afghanistan by Alexander the Great (330 BC – 327 BC)

*Muslim conquests of Afghanistan (637–709)

*Conquest of Afghanistan by the Mongol Empire (13th century), see als ...

, to overthrow the

Taliban

The Taliban (; ps, طالبان, ṭālibān, lit=students or 'seekers'), which also refers to itself by its state (polity), state name, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a Deobandi Islamic fundamentalism, Islamic fundamentalist, m ...

, destroy

al-Qaeda

Al-Qaeda (; , ) is an Islamic extremism, Islamic extremist organization composed of Salafist jihadists. Its members are mostly composed of Arab, Arabs, but also include other peoples. Al-Qaeda has mounted attacks on civilian and military ta ...

, and capture

Osama bin Laden

Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden (10 March 1957 – 2 May 2011) was a Saudi-born extremist militant who founded al-Qaeda and served as its leader from 1988 until Killing of Osama bin Laden, his death in 2011. Ideologically a Pan-Islamism ...

. In 2003, Blair supported the

2003 invasion of Iraq

The 2003 invasion of Iraq was a United States-led invasion of the Republic of Iraq and the first stage of the Iraq War. The invasion phase began on 19 March 2003 (air) and 20 March 2003 (ground) and lasted just over one month, including 26 ...

and had the British Armed Forces participate in the

Iraq War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Iraq War {{Nobold, {{lang, ar, حرب العراق (Arabic) {{Nobold, {{lang, ku, شەڕی عێراق (Kurdish languages, Kurdish)

, partof = the Iraq conflict (2003–present), I ...

, claiming that

Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein ( ; ar, صدام حسين, Ṣaddām Ḥusayn; 28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 16 July 1979 until 9 April 2003. A leading member of the revolution ...

's regime possessed

weapons of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill and bring significant harm to numerous individuals or cause great damage to artificial structures (e.g., buildings), natura ...

(WMDs); no WMDs were ever found in Iraq.

Blair was re-elected for a third term with another landslide in

2005

File:2005 Events Collage V2.png, From top left, clockwise: Hurricane Katrina in the Gulf of Mexico; the Funeral of Pope John Paul II is held in Vatican City; "Me at the zoo", the first video ever to be uploaded to YouTube; Eris was discovered in ...

, but with a substantially reduced majority. The Afghanistan and Iraq wars continued during

his third term, and in 2006, Blair announced he would resign within a year. Blair resigned as Labour leader on 24 June 2007 and as prime minister on 27 June 2007, and was succeeded by

Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. He previously served as Chance ...

, his

chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

. After leaving office, Blair gave up his seat and was appointed Special Envoy of the

Quartet on the Middle East

The Quartet on the Middle East or Middle East Quartet, sometimes called the Diplomatic Quartet or Madrid Quartet or simply the Quartet, is a foursome of nations and international and supranational entities involved in mediating the Israeli� ...

, a diplomatic post which he held until 2015. He has been the executive chairman of the

Tony Blair Institute for Global Change

The Tony Blair Institute (TBI), commonly known by its trade name the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, is a non-profit organisation set up by former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair to provide advice to governments and "to help political leader ...

since 2016, and has made occasional political interventions. In 2009, Blair was awarded the

Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merito ...

by

George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Republican Party, Bush family, and son of the 41st president George H. W. Bush, he ...

. He was

knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

by Queen

Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

in 2021.

At various points in

his premiership, Blair was among both the most popular and unpopular figures in UK history. As prime minister, he achieved the highest recorded approval ratings during his first few years in office, but also one of the lowest such ratings during and after the Iraq War. Blair had notable electoral successes and reforms, and he is usually rated as above average in

historical rankings and public opinion of British prime ministers.

Early years

Blair was born at Queen Mary Maternity Home in

Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, Scotland,

on 6 May 1953.

[ ] He was the second son of

Leo and Hazel (' Corscadden) Blair. Leo Blair was the illegitimate son of two entertainers and was adopted as a baby by

Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

shipyard worker James Blair and his wife, Mary. Hazel Corscadden was the daughter of George Corscadden, a butcher and

Orangeman who moved to Glasgow in 1916. In 1923, he returned to (and later died in)

Ballyshannon

Ballyshannon () is a town in County Donegal, Ireland. It is located at the southern end of the county where the N3 from Dublin ends and the N15 crosses the River Erne. Incorporated in 1613, it is one of the oldest towns in Ireland.

Location

B ...

, County Donegal, in

Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

. In Ballyshannon, Corscadden's wife, Sarah Margaret (née Lipsett), gave birth above the family's grocery shop to Blair's mother, Hazel.

Blair has an older brother, Sir

William Blair, a

High Court judge, and a younger sister, Sarah. Blair's first home was with his family at Paisley Terrace in the Willowbrae area of Edinburgh. During this period, his father worked as a junior tax inspector whilst also studying for a law degree from the

University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

.

Blair's first relocation was when he was nineteen months old. At the end of 1954, Blair's parents and their two sons moved from Paisley Terrace to

Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

,

South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

.

His father lectured in law at the

University of Adelaide

The University of Adelaide (informally Adelaide University) is a public research university located in Adelaide, South Australia. Established in 1874, it is the third-oldest university in Australia. The university's main campus is located on N ...

. It was when in Australia that Blair's sister Sarah was born. The Blairs lived in the suburb of

Dulwich

Dulwich (; ) is an area in south London, England. The settlement is mostly in the London Borough of Southwark, with parts in the London Borough of Lambeth, and consists of Dulwich Village, East Dulwich, West Dulwich, and the Southwark half of ...

close to the university. The family returned to the United Kingdom in the summer of 1958. They lived for a time with Hazel's mother and stepfather (William McClay) at their home in

Stepps

Stepps is a settlement in North Lanarkshire, Scotland, near the north-eastern outskirts of Glasgow. Its recently upgraded amenities include a new primary school, library and sports facilities. The town retains a historic heart around its church in ...

on the outskirts of north-east Glasgow. Blair's father accepted a job as a lecturer at

Durham University

, mottoeng = Her foundations are upon the holy hills (Psalm 87:1)

, established = (university status)

, type = Public

, academic_staff = 1,830 (2020)

, administrative_staff = 2,640 (2018/19)

, chancellor = Sir Thomas Allen

, vice_chan ...

, and thus moved the family to

Durham, England

Durham ( , locally ), is a cathedral city and civil parish on the River Wear, County Durham, England. It is an administrative centre of the County Durham District, which is a successor to the historic County Palatine of Durham (which is dif ...

. Aged five, this marked the beginning of a long association Blair was to have with Durham.

Since his childhood, Blair has been a fan of

Newcastle United

Newcastle United Football Club is an English professional football club, based in Newcastle upon Tyne, that plays in the Premier League – the top flight of English football. The club was founded in 1892 by the merger of Newcastle East End ...

football club.

Education and legal career

With his parents basing their family in Durham, Blair attended the

Chorister School

The Chorister School was a co-educational independent school for the 3 to 13 age range. It consisted of a Pre-School (opened in September 2008), a pre-preparatory and preparatory day and boarding school in Durham, England. It was set in an envia ...

from 1961 to 1966. Aged 13, he was sent to spend his school term-time boarding at

Fettes College

Fettes College () is a co-educational independent boarding and day school in Edinburgh, Scotland, with over two-thirds of its pupils in residence on campus. The school was originally a boarding school for boys only and became co-ed in 1983. In ...

in Edinburgh from 1966 to 1971.

Blair is reported to have hated his time at Fettes.

His teachers were unimpressed with him; his biographer,

John Rentoul

John Rentoul (born 1958) is a British journalist. He is the chief political commentator for ''The Independent''.

Early life

Rentoul was born in India, where his father was a minister of the Church of South India. Educated at Wolverhampton Gram ...

, reported that "All the teachers I spoke to when researching the book said he was a complete pain in the backside and they were very glad to see the back of him."

Blair reportedly modelled himself on

Mick Jagger

Sir Michael Philip Jagger (born 26 July 1943) is an English singer and songwriter who has achieved international fame as the lead vocalist and one of the founder members of the rock band the Rolling Stones. His ongoing songwriting partnershi ...

, lead singer of

The Rolling Stones

The Rolling Stones are an English rock band formed in London in 1962. Active for six decades, they are one of the most popular and enduring bands of the rock era. In the early 1960s, the Rolling Stones pioneered the gritty, rhythmically d ...

. During his time there he met

Charlie Falconer (a pupil at the rival

Edinburgh Academy

The Edinburgh Academy is an Independent school (United Kingdom), independent day school in Edinburgh, Scotland, which was opened in 1824. The original building, on Henderson Row in the city's New Town, Edinburgh, New Town, is now part of the Se ...

), whom he later appointed

lord chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. The ...

.

Leaving Fettes College at the age of 18, Blair next spent a gap year in London attempting to find fame as a rock music promoter.

In 1972, at the age of 19, Blair matriculated at

St John's College, Oxford

St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. Founded as a men's college in 1555, it has been coeducational since 1979.Communication from Michael Riordan, college archivist Its founder, Sir Thomas White, intended to pro ...

, reading

Jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning a ...

for three years. As a student, he played guitar and sang in a rock band called

Ugly Rumours, and performed some

stand-up comedy

Stand-up comedy is a comedy, comedic performance to a live audience in which the performer addresses the audience directly from the stage. The performer is known as a comedian, a comic or a stand-up.

Stand-up comedy consists of One-line joke ...

, including parodying

James T. Kirk

James Tiberius Kirk is a fictional character in the ''Star Trek'' media franchise. Originally played by Canadian actor William Shatner, Kirk first appeared in ''Star Trek'' serving aboard the starship USS ''Enterprise'' as captain. Kirk leads ...

as a character named ''Captain

Kink

Kink or KINK may refer to:

Common uses

* Kink (sexuality), a colloquial term for non-normative sexual behavior

* Kink, a curvature, bend, or twist

Geography

* Kink, Iran, a village in Iran

* The Kink, a man-made geographic feature in remote east ...

''. He was influenced by fellow student and

Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

priest

Peter Thomson Peter Thomson may refer to:

* Peter Thomson (golfer) (1929–2018), Australian golfer

* Peter Thomson (diplomat) (born 1948), Fiji's Permanent Representative to the United Nations

* Peter Thomson (footballer) (born 1977), English footballer

* Peter ...

, who awakened his religious faith and left-wing politics. While at Oxford, Blair has stated that he was briefly a

Trotskyist

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a rev ...

, after reading the first volume of

Isaac Deutscher

Isaac; grc, Ἰσαάκ, Isaák; ar, إسحٰق/إسحاق, Isḥāq; am, ይስሐቅ is one of the three patriarchs of the Israelites and an important figure in the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. He was th ...

's biography of

Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

, which was "like a light going on". He graduated from Oxford at the age of 22 in 1975 with a

second-class Honours

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied (sometimes with significant variati ...

B.A. in jurisprudence.

In 1975, while Blair was at Oxford, his mother Hazel died aged 52 of thyroid cancer, which greatly affected him.

After Oxford, Blair then became a member of

Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn is one of the four Inns of Court in London to which barristers of England and Wales belong and where they are called to the Bar. (The other three are Middle Temple, Inner Temple and Gray's Inn.) Lincoln ...

and was called to the Bar and became a pupil barrister. He met his future wife,

Cherie Booth

Cherie, Lady Blair, (; born 23 September 1954), also known professionally as Cherie Booth, is an English barrister and writer. She is married to the former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Sir Tony Blair.

Early life and education

Booth ...

(daughter of the actor

Tony Booth) at the chambers founded by

Derry Irvine

Alexander Andrew Mackay Irvine, Baron Irvine of Lairg, (born 23 June 1940), known as Derry Irvine, is a Scottish lawyer, judge and political figure who served as Lord Chancellor under his former pupil barrister, Tony Blair.

Education

Irvine ...

(who was to be Blair's first lord Chancellor), 11 King's Bench Walk Chambers.

Early political career

Blair joined the

Labour Party shortly after graduating from Oxford in 1975. In the early 1980s, he was involved in

Labour politics in

Hackney South and Shoreditch

Hackney South and Shoreditch is a constituency represented in the House of Commons of the UK Parliament since 2005 by Meg Hillier of Labour Co-op.

History

The seat was created in February 1974 from the former seat of Shoreditch and Finsbury.

...

, where he aligned himself with the "

soft left

The soft left is a faction within the British Labour Party. The term "soft left" was coined to distinguish the mainstream left of Michael Foot from the hard left of Tony Benn.

History

The distinction between hard and soft left became evident ...

" of the party. He put himself forward as a candidate for the

Hackney council

Hackney London Borough Council is the local government authority for the London Borough of Hackney, London, England, one of 32 London borough councils. The council is unusual in the United Kingdom local government system in that its executive fu ...

elections of 1982 in Queensbridge ward, a safe Labour area, but was not selected.

In 1982, Blair was selected as the Labour Party candidate for the safe

Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

seat of

Beaconsfield

Beaconsfield ( ) is a market town and civil parish within the unitary authority of Buckinghamshire, England, west-northwest of central London and south-southeast of Aylesbury. Three other towns are within : Gerrards Cross, Amersham and High W ...

, where there was a forthcoming by-election. Although Blair lost the

Beaconsfield by-election and Labour's share of the vote fell by 10 percentage points, he acquired a profile within the party. Despite his defeat, William Russell, political correspondent for ''

The Glasgow Herald

''The Herald'' is a Scottish broadsheet newspaper founded in 1783. ''The Herald'' is the longest running national newspaper in the world and is the eighth oldest daily paper in the world. The title was simplified from ''The Glasgow Herald'' in ...

'', described Blair as "a very good candidate", while acknowledging that the result was "a disaster" for the Labour Party.

In contrast to his later

centrism

Centrism is a political outlook or position involving acceptance or support of a balance of social equality and a degree of social hierarchy while opposing political changes that would result in a significant shift of society strongly to the l ...

, Blair made it clear in a letter he wrote to Labour leader

Michael Foot

Michael Mackintosh Foot (23 July 19133 March 2010) was a British Labour Party politician who served as Labour Leader from 1980 to 1983. Foot began his career as a journalist on ''Tribune'' and the ''Evening Standard''. He co-wrote the 1940 p ...

in July 1982 (published in 2006) that he had "come to Socialism through Marxism" and considered himself on the left.

Like

Tony Benn

Anthony Neil Wedgwood Benn (3 April 1925 – 14 March 2014), known between 1960 and 1963 as Viscount Stansgate, was a British politician, writer and diarist who served as a Cabinet of the United Kingdom, Cabinet minister in the 1960s and 1970s. ...

, Blair believed that the "Labour right" was bankrupt:

"Socialism ultimately must appeal to the better minds of the people. You cannot do that if you are tainted overmuch with a pragmatic period in power."

Yet, he saw the

hard left

In the United Kingdom, the hard left are the left-wing political movements and ideas outside the mainstream centre-left.*

*

Term

The term was first used in the context of debates within both the Labour Party and the broader left in the 198 ...

as no better, saying:

With a general election due, Blair had not been selected as a candidate anywhere. He was invited to stand again in Beaconsfield, and was initially inclined to agree but was advised by his head of chambers Derry Irvine to find somewhere else which might be winnable. The situation was complicated by the fact that Labour was fighting a legal action against planned boundary changes, and had selected candidates on the basis of previous boundaries. When the legal challenge failed, the party had to rerun all selections on the new boundaries; most were based on existing seats, but unusually in County Durham a new

Sedgefield

Sedgefield is a market town and civil parish in County Durham, England. It had a population of 5,211 as at the 2011 census. It has the only operating racecourse in County Durham.

History Roman

A Roman 'ladder settlement' was discovered by C ...

constituency had been created out of Labour-voting areas which had no obvious predecessor seat.

The selection for Sedgefield did not begin until after the

1983 general election was called. Blair's initial inquiries discovered that the left was trying to arrange the selection for

Les Huckfield

Leslie John Huckfield (born 7 April 1942) is a British Labour politician who served as Member of Parliament (MP) for Nuneaton from 1967 to 1983 and as a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) from 1984 to 1989.

Early life

From 1960 to 1963, Huc ...

, sitting MP for Nuneaton who was trying elsewhere; several sitting MPs displaced by boundary changes were also interested in it. When he discovered the

Trimdon branch had not yet made a nomination, Blair visited them and won the support of the branch secretary

John Burton, and with Burton's help was nominated by the branch. At the last minute, he was added to the shortlist and won the selection over Huckfield. It was the last candidate selection made by Labour before the election, and was made after the Labour Party had issued biographies of all its candidates ("Labour's Election Who's Who").

John Burton became Blair's

election agent

An election agent in elections in the United Kingdom, as well as some other similar political systems such as elections in India, is the person legally responsible for the conduct of a candidate's political campaign and to whom election material is ...

and one of his most trusted and longest-standing allies. Blair's election literature in the 1983 general election endorsed left-wing policies that Labour advocated in the early 1980s. He called for Britain to leave the

EEC

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisb ...

as early as the 1970s, though he had told his selection conference that he personally favoured continuing membership and voted "Yes" in the

1975 referendum on the subject. He opposed the

Exchange Rate Mechanism

The European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) is a system introduced by the European Economic Community on 1 January 1999 alongside the introduction of a single currency, the euro (replacing ERM 1 and the euro's predecessor, the ECU) as p ...

(ERM) in 1986 but supported the ERM by 1989. He was a member of the

Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) is an organisation that advocates unilateral nuclear disarmament by the United Kingdom, international nuclear disarmament and tighter international arms regulation through agreements such as the Nucle ...

, despite never strongly being in favour of

unilateral nuclear disarmament

__NOTOC__

Unilateralism is any doctrine or agenda that supports one-sided action. Such action may be in disregard for other parties, or as an expression of a commitment toward a direction which other parties may find disagreeable. As a word, ''un ...

.

Blair was helped on the campaign trail by soap opera actress

Pat Phoenix

Patricia Phoenix Booth (born Patricia Frederica Manfield; 26 November 1923 – 17 September 1986) was an English actress who became one of the first sex symbols of British television through her role as Elsie Tanner, an original cast member ...

, his father-in-law's girlfriend. At the age of thirty, he was elected as MP for Sedgefield in 1983; despite the party's

landslide defeat at the general election.

In his

maiden speech

A maiden speech is the first speech given by a newly elected or appointed member of a legislature or parliament.

Traditions surrounding maiden speeches vary from country to country. In many Westminster system governments, there is a convention th ...

in the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

on 6 July 1983, Blair stated, "I am a socialist not through reading a textbook that has caught my intellectual fancy, nor through unthinking tradition, but because I believe that, at its best, socialism corresponds most closely to an existence that is both rational and moral. It stands for cooperation, not confrontation; for fellowship, not fear. It stands for equality."

Once elected, Blair's political ascent was rapid. He received his first

front-bench

In many parliaments and other similar assemblies, seating is typically arranged in banks or rows, with each political party or caucus grouped together. The spokespeople for each group will often sit at the front of their group, and are then know ...

appointment in 1984 as assistant

Treasury

A treasury is either

*A government department related to finance and taxation, a finance ministry.

*A place or location where treasure, such as currency or precious items are kept. These can be state or royal property, church treasure or in p ...

spokesman. In May 1985, he appeared on BBC's ''

Question Time

A question time in a parliament occurs when members of the parliament ask questions of government ministers (including the prime minister), which they are obliged to answer. It usually occurs daily while parliament is sitting, though it can be ca ...

'', arguing that the Conservative Government's

Public Order White Paper was a threat to civil liberties.

Blair demanded an inquiry into the

Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government of ...

's decision to rescue the collapsed

Johnson Matthey

Johnson Matthey is a British multinational speciality chemicals and sustainable technologies company headquartered in London, England. It is listed on the London Stock Exchange and is a constituent of the FTSE 250 Index.

History Early years

...

bank in October 1985. By this time, Blair was aligned with the reforming tendencies in the party (headed by leader

Neil Kinnock

Neil Gordon Kinnock, Baron Kinnock (born 28 March 1942) is a British former politician. As a member of the Labour Party, he served as a Member of Parliament from 1970 until 1995, first for Bedwellty and then for Islwyn. He was the Leader of ...

) and was promoted after the

1987 election to the Shadow

Trade and Industry team as spokesman on the

City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

.

Leadership roles

In 1987, he stood for

election to the Shadow Cabinet, receiving 71 votes. When Kinnock resigned after a fourth consecutive Conservative victory in the

1992 general election, Blair became

shadow home secretary

In British politics, the Shadow Home Secretary (formally known as the Shadow Secretary of State for the Home Department) is the person within the shadow cabinet who shadows the Home Secretary; this effectively means scrutinising government polic ...

under

John Smith. The old guard argued that trends showed they were regaining strength under Smith's strong leadership. Meanwhile, the breakaway

SDP faction had merged with the

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

; the resulting

Liberal Democrats seemed to pose a major threat to the Labour base. Blair, the leader of the modernising faction, had an entirely different vision, arguing that the long-term trends had to be reversed. The Labour Party was too locked into a base that was shrinking, since it was based on the working-class, on trade unions, and on residents of subsidised council housing. The rapidly growing middle-class was largely ignored, especially the more ambitious working-class families. They aspired to middle-class status but accepted the Conservative argument that Labour was holding ambitious people back with its levelling-down policies. They increasingly saw Labour in terms defined by the opposition, regarding higher taxes and higher interest rates. The steps towards what would become New Labour were procedural but essential. Calling on the slogan "

One member, one vote

In the parliamentary politics of the United Kingdom and Canada, one member, one vote (OMOV) is a method of selecting party leaders, and determining party policy, by a direct vote of the members of a political party. Traditionally, these objectives ...

", John Smith (with limited input from Blair) secured an end to the trade union block vote for Westminster candidate selection at the 1993 conference. But Blair and the modernisers wanted Smith to go further still, and called for radical adjustment of Party goals by repealing "Clause IV," the historic commitment to

nationalisation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

of industry. This would be achieved in 1995.

Leader of the Opposition

John Smith died suddenly in 1994 of a heart attack. Blair defeated

John Prescott

John Leslie Prescott, Baron Prescott (born 31 May 1938) is a British politician who served as Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and as First Secretary of State from 2001 to 2007. A member of the Labour Party, he w ...

and

Margaret Beckett

Dame Margaret Mary Beckett (''née'' Jackson; born 15 January 1943) is a British politician who has served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Derby South since 1983. A member of the Labour Party, she became Britain's first female Foreign S ...

in the

subsequent leadership election and became

Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

.

As is customary for the holder of that office, Blair was appointed a

Privy Councillor

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

.

During his speech at the 1994 Labour Party conference, Blair announced a forthcoming proposal to update the party's objects and objectives, which was widely interpreted to relate to replacing

Clause IV

Clause IV is part of the Labour Party Rule Book, which sets out the aims and values of the (UK) Labour Party. The original clause, adopted in 1918, called for common ownership of industry, and proved controversial in later years; Hugh Gaitskell a ...

of the party's constitution with a new statement of aims and values.

This involved the deletion of the party's stated commitment to "the common ownership of the means of production and exchange", which was generally understood to mean wholesale nationalisation of major industries.

At a special conference in April 1995, the clause was replaced by a statement that the party is "

democratic socialist

Democratic socialism is a left-wing political philosophy that supports political democracy and some form of a socially owned economy, with a particular emphasis on economic democracy, workplace democracy, and workers' self-management within a ...

",

and Blair also claimed to be a "democratic socialist" himself in the same year. However, the move away from nationalisation in the old Clause IV made many on the left-wing of the Labour Party feel that Labour was moving away from traditional socialist principles of nationalisation set out in 1918, and was seen by them as part of a shift of the party towards "

New Labour

New Labour was a period in the history of the British Labour Party from the mid to late 1990s until 2010 under the leadership of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. The name dates from a conference slogan first used by the party in 1994, later seen ...

".

He inherited the Labour leadership at a time when the party was ascendant over the Conservatives in the opinion polls, since the Conservative government's reputation in monetary policy was left in tatters by the

Black Wednesday

Black Wednesday (or the 1992 Sterling crisis) occurred on 16 September 1992 when the UK Government was forced to withdraw sterling from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), after a failed attempt to keep its exchange rate above the ...

economic disaster of September 1992. Blair's election as leader saw Labour support surge higher still

in spite of the continuing economic recovery and fall in unemployment that the Conservative government (led by

John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997, and as Member of Parliament ...

) had overseen since the end of the 1990–92

recession

In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction when there is a general decline in economic activity. Recessions generally occur when there is a widespread drop in spending (an adverse demand shock). This may be triggered by various ...

.

At the 1996 Labour Party conference, Blair stated that his three top priorities on coming to office were "education, education, and education".

Aided by the unpopularity of John Major's Conservative government (itself deeply divided over the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

), "New Labour" won a landslide victory at the

1997 general election, ending eighteen years of Conservative Party rule, with the heaviest Conservative defeat since

1906

Events

January–February

* January 12 – Persian Constitutional Revolution: A nationalistic coalition of merchants, religious leaders and intellectuals in Persia forces the shah Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar to grant a constitution, ...

.

According to diaries released by

Paddy Ashdown

Jeremy John Durham Ashdown, Baron Ashdown of Norton-sub-Hamdon, (27 February 194122 December 2018), better known as Paddy Ashdown, was a British politician and diplomat who served as Leader of the Liberal Democrats from 1988 to 1999. Internati ...

, during Smith's leadership of the Labour Party, there were discussions with Ashdown about forming a

coalition

A coalition is a group formed when two or more people or groups temporarily work together to achieve a common goal. The term is most frequently used to denote a formation of power in political or economical spaces.

Formation

According to ''A Gui ...

government if the next general election resulted in a

hung parliament

A hung parliament is a term used in legislatures primarily under the Westminster system to describe a situation in which no single political party or pre-existing coalition (also known as an alliance or bloc) has an absolute majority of legisl ...

. Ashdown also claimed that Blair was a supporter of

proportional representation

Proportional representation (PR) refers to a type of electoral system under which subgroups of an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body. The concept applies mainly to geographical (e.g. states, regions) and political divis ...

(PR).

In addition to Ashdown, Liberal Democrat MPs

Menzies Campbell

Walter Menzies Campbell, Baron Campbell of Pittenweem, (; born 22 May 1941), often known as Ming Campbell, is a British Liberal Democrat politician, advocate and former athlete. He was the Member of Parliament (MP) for North East Fife from ...

and

Alan Beith

Alan James Beith, Baron Beith, (born 20 April 1943) is a British Liberal Democrat politician who represented Berwick-upon-Tweed as its Member of Parliament (MP) from 1973 to 2015.

From 1992 to 2003 he was Deputy Leader of the Liberal Democrat ...

were earmarked for places in the cabinet if a Labour-Lib Dem coalition was formed.

Blair was forced to back down on these proposals because John Prescott and

Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. He previously served as Chance ...

opposed the PR system, and many members of the Shadow Cabinet were worried about concessions being made towards the Lib Dems.

In the event, virtually every opinion poll since late-1992 put Labour ahead with enough support to form an overall majority.

Prime Minister (1997–2007)

Blair became the

prime minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern pr ...

on 2 May 1997. Aged 43, Blair became the youngest person to become prime minister since

Lord Liverpool

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool, (7 June 1770 – 4 December 1828) was a British Tory statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1812 to 1827. He held many important cabinet offices such as Foreign Secret ...

became prime minister aged 42 in 1812, and until

Rishi Sunak

Rishi Sunak (; born 12 May 1980) is a British politician who has served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party since October 2022. He previously held two Cabinet of ...

became prime minister in 2022. He was also the first prime minister born after

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

and the accession of

Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

to the throne. With victories in 1997,

2001 United Kingdom general election, 2001, and

2005

File:2005 Events Collage V2.png, From top left, clockwise: Hurricane Katrina in the Gulf of Mexico; the Funeral of Pope John Paul II is held in Vatican City; "Me at the zoo", the first video ever to be uploaded to YouTube; Eris was discovered in ...

, Blair was the Labour Party's longest-serving prime minister, and the first and only person to date to lead the party to three consecutive general election victories.

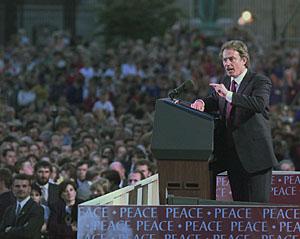

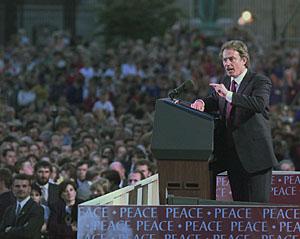

Northern Ireland

His contribution towards assisting the

Northern Ireland peace process

The Northern Ireland peace process includes the events leading up to the 1994 Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) ceasefire, the end of most of the violence of the Troubles, the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, and subsequent political developm ...

by helping to negotiate the

Good Friday Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement (GFA), or Belfast Agreement ( ga, Comhaontú Aoine an Chéasta or ; Ulster-Scots: or ), is a pair of agreements signed on 10 April 1998 that ended most of the violence of The Troubles, a political conflict in No ...

(after 30 years of conflict) was widely recognised. Following the

Omagh bombing

The Omagh bombing was a car bombing on 15 August 1998 in the town of Omagh in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland. It was carried out by the Real Irish Republican Army (Real IRA), a Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) splinter group who oppose ...

on 15 August 1998, by members of the

Real IRA

The Real Irish Republican Army, or Real IRA (RIRA), is a dissident Irish republican paramilitary group that aims to bring about a United Ireland. It formed in 1997 following a split in the Provisional IRA by dissident members, who rejected the ...

opposed to the peace process, which killed 29 people and wounded hundreds, Blair visited the

County Tyrone

County Tyrone (; ) is one of the six Counties of Northern Ireland, counties of Northern Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the thirty-two traditional Counties of Ireland, counties of Ireland. It is no longer used as an admini ...

town and met with victims at

Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast

The Royal Victoria Hospital commonly known as "the Royal", the "RVH" or "the Royal Belfast", is a hospital in Belfast, Northern Ireland. It is managed by the Belfast Health and Social Care Trust. The hospital has a Regional Virus Centre, which ...

.

Military intervention and the War on Terror

In his first six years in office, Blair ordered British troops into combat five times, more than any other prime minister in British history. This included Iraq in both

1998

1998 was designated as the ''International Year of the Ocean''.

Events January

* January 6 – The '' Lunar Prospector'' spacecraft is launched into orbit around the Moon, and later finds evidence for frozen water, in soil in permanently ...

and

2003

File:2003 Events Collage.png, From top left, clockwise: The crew of STS-107 perished when the Space Shuttle Columbia disintegrated during reentry into Earth's atmosphere; SARS became an epidemic in China, and was a precursor to SARS-CoV-2; A des ...

,

Kosovo

Kosovo ( sq, Kosova or ; sr-Cyrl, Косово ), officially the Republic of Kosovo ( sq, Republika e Kosovës, links=no; sr, Република Косово, Republika Kosovo, links=no), is a partially recognised state in Southeast Euro ...

(1999),

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierra ...

(2000) and

War in Afghanistan (2001–2021), Afghanistan (2001).

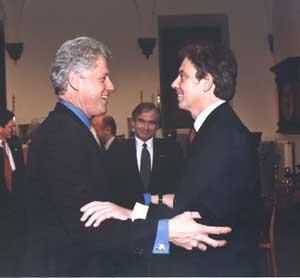

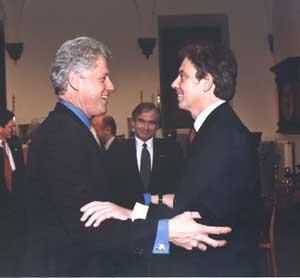

The Kosovo War, which Blair had advocated on moral grounds, was initially a failure when it relied solely on air strikes; the threat of a ground offensive convinced Serbia's

Slobodan Milošević

Slobodan Milošević (, ; 20 August 1941 – 11 March 2006) was a Yugoslav and Serbian politician who was the president of Serbia within Yugoslavia from 1989 to 1997 (originally the Socialist Republic of Serbia, a constituent republic of ...

to withdraw. Blair had been a major advocate for a ground offensive, which

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

was reluctant to do, and ordered that 50,000 soldiers – most of the available British Army – should be made ready for action. The following year, the limited

Operation Palliser

The United Kingdom began a military intervention in Sierra Leone on 7 May 2000 under the codename Operation Palliser. Although small numbers of British personnel had been deployed previously, Palliser was the first large-scale intervention by B ...

in Sierra Leone swiftly swung the tide against the rebel forces; before deployment, the

United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone

The United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL) was a United Nations peacekeeping operation in Sierra Leone from 1999 to 2006. It was created by the United Nations Security Council in October 1999 to help with the implementation of the Lom� ...

had been on the verge of collapse. Palliser had been intended as an evacuation mission but

Brigadier David Richards was able to convince Blair to allow him to expand the role; at the time, Richards' action was not known and Blair was assumed to be behind it.

Blair ordered

Operation Barras

Operation Barras was a British Army operation that took place in Sierra Leone on 10 September 2000, during the late stages of Sierra Leone Civil War, the nation's civil war. The operation aimed to release five British soldiers of the Royal Ir ...

, a highly successful

SAS

SAS or Sas may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''SAS'' (novel series), a French book series by Gérard de Villiers

* ''Shimmer and Shine'', an American animated children's television series

* Southern All Stars, a Japanese rock ba ...

/

Parachute Regiment strike to rescue hostages from a Sierra Leone rebel group. Journalist

Andrew Marr

Andrew William Stevenson Marr (born 31 July 1959) is a British journalist and broadcaster. Beginning his career as a political commentator, he subsequently edited ''The Independent'' newspaper from 1996 to 1998 and was political editor of BBC N ...

has argued that the success of ground attacks, real and threatened, over air strikes alone was influential on how Blair planned the Iraq War, and that the success of the first three wars Blair fought "played to his sense of himself as a moral war leader". When asked in 2010 if the success of Palliser may have "embolden

dBritish politicians" to think of military action as a policy option, General Sir David Richards admitted there "might be something in that".

From the start of the

War on Terror

The war on terror, officially the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT), is an ongoing international Counterterrorism, counterterrorism military campaign initiated by the United States following the September 11 attacks. The main targets of the campa ...

in 2001, Blair strongly supported the

foreign policy

A State (polity), state's foreign policy or external policy (as opposed to internal or domestic policy) is its objectives and activities in relation to its interactions with other states, unions, and other political entities, whether bilaterall ...

of

George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Republican Party, Bush family, and son of the 41st president George H. W. Bush, he ...

, participating in the

2001 invasion of Afghanistan

In late 2001, the United States and its close allies invaded Afghanistan and toppled the Taliban government. The invasion's aims were to dismantle al-Qaeda, which had executed the September 11 attacks, and to deny it a safe base of operations ...

and

2003 invasion of Iraq

The 2003 invasion of Iraq was a United States-led invasion of the Republic of Iraq and the first stage of the Iraq War. The invasion phase began on 19 March 2003 (air) and 20 March 2003 (ground) and lasted just over one month, including 26 ...

. The invasion of Iraq was particularly controversial, as it attracted widespread public opposition and 139 of Blair's own MPs opposed it.

As a result, he faced criticism over the policy itself and the circumstances of the decision.

Alastair Campbell

Alastair John Campbell (born 25 May 1957) is a British journalist, author, strategist, broadcaster and activist known for his roles during Tony Blair's leadership of the Labour Party. Campbell worked as Blair's spokesman and campaign director ...

described Blair's statement that the intelligence on WMDs was "beyond doubt" as his "assessment of the assessment that was given to him." In 2009, Blair stated that he would have supported removing

Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein ( ; ar, صدام حسين, Ṣaddām Ḥusayn; 28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 16 July 1979 until 9 April 2003. A leading member of the revolution ...

from power even in the face of proof that he had no such weapons. Playwright

Harold Pinter

Harold Pinter (; 10 October 1930 – 24 December 2008) was a British playwright, screenwriter, director and actor. A Nobel Prize winner, Pinter was one of the most influential modern British dramatists with a writing career that spanne ...

and former Malaysian Prime Minister

Mahathir Mohamad

Mahathir bin Mohamad ( ms, محاضير بن محمد, label= Jawi, script=arab, italic=unset; ; born 10 July 1925) is a Malaysian politician, author, and physician who served as the 4th and 7th Prime Minister of Malaysia. He held the office ...

accused Blair of war crimes.

Testifying before the

Iraq Inquiry

The Iraq Inquiry (also referred to as the Chilcot Inquiry after its chairman, Sir John Chilcot)[11 September attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated Suicide attack, suicide List of terrorist incidents, terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, ...]

. Blair denied that he would have supported the invasion of Iraq even if he had thought Saddam had no weapons of mass destruction. He said he believed the world was safer as a result of the invasion. He said there was "no real difference between wanting regime change and wanting Iraq to disarm: regime change was US policy because Iraq was in breach of its UN obligations." In an October 2015

CNN

CNN (Cable News Network) is a multinational cable news channel headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. Founded in 1980 by American media proprietor Ted Turner and Reese Schonfeld as a 24-hour cable news channel, and presently owned by the M ...

interview with

Fareed Zakaria

Fareed Rafiq Zakaria (; born 20 January 1964) is an Indian-American journalist, political commentator, and author. He is the host of CNN's ''Fareed Zakaria GPS'' and writes a weekly paid column for ''The Washington Post.'' He has been a columnist ...

, Blair apologised for his "mistakes" over Iraq War and admitted there were "elements of truth" to the view that the invasion helped promote the rise of

ISIS

Isis (; ''Ēse''; ; Meroitic: ''Wos'' 'a''or ''Wusa''; Phoenician: 𐤀𐤎, romanized: ʾs) was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kingd ...

. The

Chilcot Inquiry

The Iraq Inquiry (also referred to as the Chilcot Inquiry after its chairman, Sir John Chilcot)[Prime Minister's Questions

Prime Minister's Questions (PMQs, officially known as Questions to the Prime Minister, while colloquially known as Prime Minister's Question Time) is a constitutional convention in the United Kingdom, currently held as a single session every W ...]

held on Tuesdays and Thursdays with a single 30-minute session on Wednesdays. In addition to PMQs, Blair held monthly press conferences at which he fielded questions from journalists and – from 2002 – broke precedent by agreeing to give evidence twice yearly before the most senior Commons select committee, the

Liaison Committee. Blair was sometimes perceived as paying insufficient attention both to the views of his own Cabinet colleagues and to those of the House of Commons. His style was sometimes criticised as not that of a prime minister and

head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, a gro ...

, which he was, but of a president and head of state – which he was not. Blair was accused of excessive reliance on

spin

Spin or spinning most often refers to:

* Spinning (textiles), the creation of yarn or thread by twisting fibers together, traditionally by hand spinning

* Spin, the rotation of an object around a central axis

* Spin (propaganda), an intentionally b ...

.

He was the first UK prime minister to have been formally questioned by police, though not

under caution, while still in office.

Events before resignation

As the

casualties of the Iraq War

Estimates of the casualties from the Iraq War (beginning with the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and the ensuing occupation and insurgency and civil war) have come in several forms, and those estimates of different types of Iraq War casualties vary gr ...

mounted, Blair was accused of misleading Parliament, and his popularity dropped dramatically.

Labour's overall majority at the 2005 general election was reduced from 167 to 66 seats. As a combined result of the

Blair–Brown pact, Iraq war and low approval ratings, pressure built up within the Labour Party for Blair to resign. Over the summer of 2006 many MPs, including usually supportive MPs, criticised Blair for not calling for a ceasefire in the

2006 Israel–Lebanon conflict

The 2006 Lebanon War, also called the 2006 Israel–Hezbollah War and known in Lebanon as the July War ( ar, حرب تموز, ''Ḥarb Tammūz'') and in Israel as the Second Lebanon War ( he, מלחמת לבנון השנייה, ''Milhemet Leva ...

. On 7 September 2006, Blair publicly stated he would step down as party leader by the time of the

Trades Union Congress

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) is a national trade union centre

A national trade union center (or national center or central) is a federation or confederation of trade unions in a country. Nearly every country in the world has a national tra ...

(TUC) conference held 10–13 September 2007,

having promised to serve a full term during the previous general election campaign. On 10 May 2007, during a speech at the Trimdon Labour Club, Blair announced his intention to resign as both Labour Party leader and prime minister. This triggered the

2007 Labour Party leadership election, in which Brown was the only candidate for leader.

At a special party conference in

Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

on 24 June 2007, Blair formally handed over the leadership of the Labour Party to Gordon Brown, who had been

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

in Blair's three ministries.

Blair tendered his resignation on 27 June 2007 and Brown assumed office during the same afternoon. Blair resigned from his Sedgefield seat in the House of Commons in the traditional form of accepting the

Stewardship of the Chiltern Hundreds

The Chiltern Hundreds is an ancient administrative area in Buckinghamshire, England, composed of three " hundreds" and lying partially within the Chiltern Hills. "Taking the Chiltern Hundreds" refers to one of the legal fictions used to effect r ...

, to which he was appointed by Gordon Brown in one of the latter's last acts as Chancellor of the Exchequer.

The resulting

Sedgefield by-election was won by Labour's candidate,

Phil Wilson. Blair decided not to issue a list of

Resignation Honours

The Prime Minister's Resignation Honours in the United Kingdom are Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, honours granted at the behest of an outgoing Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, prime minister following their resignation ...

, making him the first prime minister of the modern era not to do so.

Policies

Social reforms

In 2001, Blair said, "We are a

left of centre

Centre-left politics lean to the left on the left–right political spectrum but are closer to the centre than other left-wing politics. Those on the centre-left believe in working within the established systems to improve social justice. The ce ...

party, pursuing economic prosperity and social justice as partners and not as opposites". Blair rarely applies such labels to himself, but he promised before the 1997 election that New Labour would govern "from the radical centre", and according to one lifelong Labour Party member, has always described himself as a

social democrat

Social democracy is a Political philosophy, political, Social philosophy, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocati ...

. However, in a 2007 opinion piece in ''

The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'', left-wing commentator Neil Lawson described Blair as to the

right of centre

Centre-right politics lean to the right of the political spectrum, but are closer to the centre. From the 1780s to the 1880s, there was a shift in the Western world of social class structure and the economy, moving away from the nobility and merc ...

. A

YouGov

YouGov is a British international Internet-based market research and data analytics firm, headquartered in the UK, with operations in Europe, North America, the Middle East and Asia-Pacific. In 2007, it acquired US company Polimetrix, and sinc ...

opinion poll in 2005 found that a small majority of British voters, including many New Labour supporters, placed Blair on the right of the political spectrum. The ''

Financial Times

The ''Financial Times'' (''FT'') is a British daily newspaper printed in broadsheet and published digitally that focuses on business and economic current affairs. Based in London, England, the paper is owned by a Japanese holding company, Nik ...

'' on the other hand has argued that Blair is not conservative, but instead a

populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term developed ...

.

Critics and admirers tend to agree that Blair's electoral success was based on his ability to occupy the centre ground and appeal to voters across the political spectrum, to the extent that he has been fundamentally at odds with traditional Labour Party values. Some left-wing critics, such as

Mike Marqusee __NOTOC__

Mike Marqusee (; 27 January 1953 – 13 January 2015) was an American writer, journalist and political activist in London.

Marqusee's first published work was the essay "Turn Left at Scarsdale", written when he was a sixteen-year-old high ...

in 2001, argued that Blair oversaw the final stage of a long term shift of the Labour Party to the right.

There is some evidence that Blair's long term dominance of the centre forced his Conservative opponents to shift a long distance to the left to challenge his

hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states. In Ancient Greece (8th BC – AD 6th ), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' city-state over oth ...

there. Leading Conservatives of the post-New Labour era hold Blair in high regard:

George Osborne

George Gideon Oliver Osborne (born Gideon Oliver Osborne; 23 May 1971) is a former British politician and newspaper editor who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 2010 to 2016 and as First Secretary of State from 2015 to 2016 in the ...

describes him as "the master",

Michael Gove

Michael Andrew Gove (; born Graeme Andrew Logan, 26 August 1967) is a British politician serving as Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities and Minister for Intergovernmental Relations since 2021. He has been Member of Parli ...

thought he had an "entitlement to conservative respect" in February 2003, while

David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron (born 9 October 1966) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2005 to 2016. He previously served as Leader o ...

reportedly maintained Blair as an informal adviser.

Blair increased police powers by adding to the number of arrestable offences, compulsory

DNA recording and the use of dispersal orders. Under Blair's government the amount of new legislation increased which attracted criticism. He also introduced tough anti-terrorism and

identity card legislation.

Economic policies

During his time as prime minister, Blair raised taxes; introduced a

National Minimum Wage

The National Minimum Wage Act 1998 creates a minimum wage across the United Kingdom.. E McGaughey, ''A Casebook on Labour Law'' (Hart 2019) ch 6(1) From 1 April 2022 this was £9.50 for people age 23 and over, £9.18 for 21- to 22-year-olds, £6. ...

and some new employment rights (while keeping

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. S ...

's trade union reforms); introduced significant constitutional reforms; promoted new rights for gay people in the

Civil Partnership Act 2004

The Civil Partnership Act 2004 (c 33) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, introduced by the Labour government, which grants civil partnerships in the United Kingdom the rights and responsibilities very similar to those in civil ...

; and signed treaties integrating Britain more closely with the EU. He introduced substantial market-based reforms in the education and health sectors; introduced student

tuition fees

Tuition payments, usually known as tuition in American English and as tuition fees in English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth English, are fees charged by education institutions for instruction or other services. Besides public spen ...

and sought to reduce certain categories of welfare payments. He did not reverse the

privatisation of the railways enacted by his predecessor John Major and instead strengthened regulation (by creating the

Office of Rail Regulation

The Office of Rail and Road (ORR) is a non-ministerial government department responsible for the economic and safety regulation of Britain's railways, and the economic monitoring of National Highways.

ORR regulates Network Rail by setting its ...

) and limited fare rises to

inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reductio ...

+1%.

Blair and Brown raised spending on the NHS and other public services, increasing spending from 39.9% of GDP to 48.1% in 2010–11. They pledged in 2001 to bring NHS spending to the levels of other European countries, and doubled spending in real terms to over £100 billion in England alone.

Immigration

Non-European immigration rose significantly during the period from 1997, not least because of the

government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...