Antarctic Station on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Multiple governments have set up permanent research stations in Antarctica and these bases are widely distributed. Unlike the

Multiple governments have set up permanent research stations in Antarctica and these bases are widely distributed. Unlike the

During the

During the

Multiple governments have set up permanent research stations in Antarctica and these bases are widely distributed. Unlike the

Multiple governments have set up permanent research stations in Antarctica and these bases are widely distributed. Unlike the drifting ice station

A drifting ice station is a temporary or semi-permanent facility built on an ice floe. During the Cold War the Soviet Union and the United States maintained a number of stations in the Arctic Ocean on floes such as Fletcher's Ice Island for rese ...

s set up in the Arctic, the research station

Research stations are facilities where scientific investigation, collection, analysis and experimentation occurs. A research station is a facility that is built for the purpose of conducting scientific research. There are also many types of resear ...

s of the Antarctic

The Antarctic ( or , American English also or ; commonly ) is a polar region around Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau and other ...

are constructed either on rock or on ice that is (for practical purposes) fixed in place.

Many of the stations are staffed throughout the year. A total of 42 countries (as of October 2006), all signatories to the Antarctic Treaty

russian: link=no, Договор об Антарктике es, link=no, Tratado Antártico

, name = Antarctic Treaty System

, image = Flag of the Antarctic Treaty.svgborder

, image_width = 180px

, caption ...

, operate seasonal (summer) and year-round research stations on the continent. The population of people performing and supporting scientific research on the continent and nearby islands varies from approximately 4,000 during the summer season to 1,000 during winter (June). In addition to these permanent stations, approximately 30 field camps are established each summer to support specific projects.

History

First bases

During the

During the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration was an era in the exploration of the continent of Antarctica which began at the end of the 19th century, and ended after the First World War; the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition of 1921–1922 is often cit ...

in the late 19th century, the first bases on the continent were established. In 1898, Carsten Borchgrevink

Carsten Egeberg Borchgrevink (1 December 186421 April 1934) was an Anglo-Norwegian polar explorer and a pioneer of Antarctic travel. He inspired Sir Robert Falcon Scott, Sir Ernest Shackleton, Roald Amundsen, and others associated with the Hero ...

, a Norwegian/British explorer, led the British Antarctic Expedition to Cape Adare

Cape Adare is a prominent cape of black basalt forming the northern tip of the Adare Peninsula and the north-easternmost extremity of Victoria Land, East Antarctica.

Description

Marking the north end of Borchgrevink Coast and the west e ...

, where he established the first Antarctic base on Ridley Beach

The Adare Peninsula, sometimes called the Cape Adare Peninsula, is a high ice-covered peninsula, long, in the northeast part of Victoria Land, extending south from Cape Adare to Cape Roget. The peninsula is considered the southernmost point of t ...

. This expedition is often referred to now as the ''Southern Cross'' Expedition, after the expedition's ship name. Most of the staff were Norwegian, but the funds for the expedition were British, provided by Sir George Newnes

Sir George Newnes, 1st Baronet (13 March 1851 – 9 June 1910) was a British publisher and editor and a founding figure in popular journalism. Newnes also served as a Liberal Party Member of Parliament for two decades. His company, George Newnes ...

. The 10 members of the expedition explored Robertson Bay

Robertson Bay is a large, roughly triangular bay that indents the north coast of Victoria Land between Cape Barrow and Cape Adare. Discovered in 1841 by Captain James Clark Ross, Royal Navy, who named it for Dr. John Robertson, Surgeon on HMS ''T ...

to the west of Cape Adare by dog teams, and later, after being picked up by the ship at the base, went ashore on the Ross Ice Shelf

The Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf of Antarctica (, an area of roughly and about across: about the size of France). It is several hundred metres thick. The nearly vertical ice front to the open sea is more than long, and between hi ...

for brief journeys. The expedition hut is still in good condition and visited frequently by tourists.

The hut was later occupied by Scott's Northern Party under the command of Victor Campbell for a year in 1911, after its attempt to explore the eastern end of the ice shelf discovered Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Amundsen bega ...

already ashore preparing for his assault on the South Pole.

In 1903, Dr William S. Bruce

William Speirs Bruce (1 August 1867 – 28 October 1921) was a British naturalist, polar scientist and oceanographer who organized and led the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition (SNAE, 1902–04) to the South Orkney Islands and the Wedde ...

's Scottish National Antarctic Expedition

The Scottish National Antarctic Expedition (SNAE), 1902–1904, was organised and led by William Speirs Bruce, a natural scientist and former medical student from the University of Edinburgh. Although overshadowed in terms of prestige by Robe ...

set off to Antarctica, with one of its aims to establish a meteorological station in the area. After the expedition failed to find land, Bruce decided to head back to the Laurie Island

Laurie Island is the second largest of the South Orkney Islands. The island is claimed by both Argentina as part of Argentine Antarctica, and the United Kingdom as part of the British Antarctic Territory. However, under the Antarctic Treaty Sy ...

in the South Orkneys

The South Orkney Islands are a group of islands in the Southern Ocean, about north-east of the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula The islands were well-situated as a site for a meteorological station, and their relative proximity to the South American mainland allowed a permanent station to be established. Bruce instituted a comprehensive programme of work, involving meteorological readings, trawling for marine samples, botanical excursions, and the collection of biological and geological specimens.

The major task completed during this time was the construction of a stone building, christened "Omond House". This was to act as living accommodation for the parties that would remain on Laurie Island to operate the proposed meteorological laboratory. The building was constructed from local materials using the  Prior to the start of the war, German aircraft had dropped markers with swastikas across

Prior to the start of the war, German aircraft had dropped markers with swastikas across

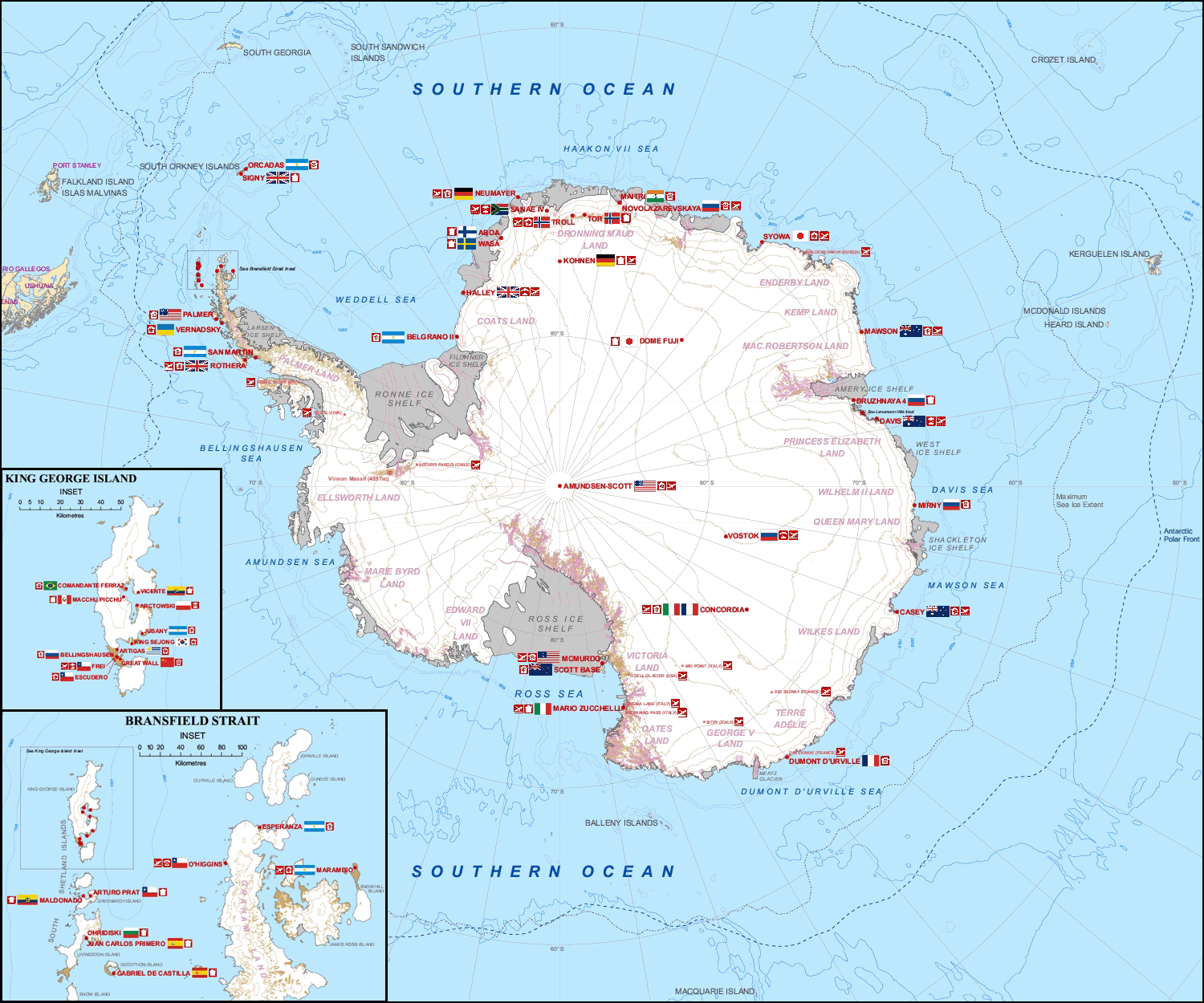

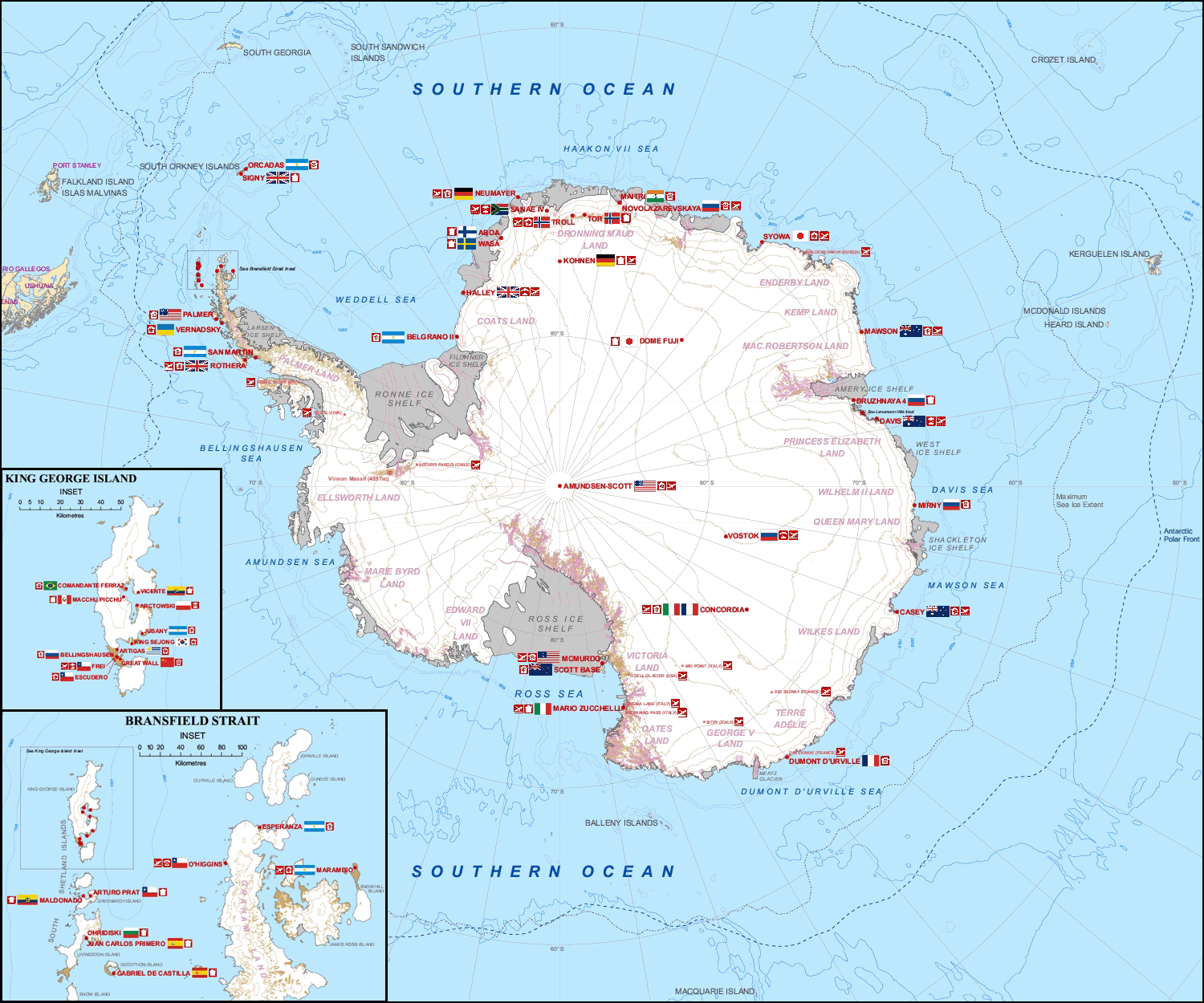

Research stationsCOMNAP Antarctic Facilities (Updated February 2014 - Excel File)

COMNAP Antarctic Facilities Map

()

Antarctic Exploration Timeline

animated map of Antarctic exploration and settlement, showing where and when Antarctic research stations were established

Antarctic Digital Database Map Viewer

SCAR {{Polar exploration Antarctica-related lists Government research Science and technology in Antarctica Antarctic research Research-related lists

dry stone

Dry stone, sometimes called drystack or, in Scotland, drystane, is a building method by which structures are constructed from stones without any mortar to bind them together. Dry stone structures are stable because of their construction m ...

method, with a roof improvised from wood and canvas sheeting. The completed house was 20 feet by 20 feet square (6m × 6m), with two windows, fitted as quarters for six people. Rudmose Brown wrote: "Considering that we had no mortar and no masons' tools it is a wonderfully fine house and very lasting. I should think it will be standing a century hence ..."

Bruce later offered to Argentina the transfer of the station and instruments on the condition that the government committed itself to the continuation of the scientific mission. Bruce informed the British officer William Haggard of his intentions in December 1903, and Haggard ratified the terms of Bruce's proposition.

The ''Scotia'' sailed back for Laurie Island on 14 January 1904 carrying on board Argentinean officials from the Ministry of Agriculture, National Meteorological Office, Ministry of Livestock and National Postal and Telegraphs Office. In 1906, Argentina communicated to the international community the establishment of a permanent base on the South Orkney Islands

The South Orkney Islands are a group of islands in the Southern Ocean, about north-east of the tip of the Antarctic PeninsulaSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, when the British launched Operation Tabarin

Operation Tabarin was the code name for a secret British expedition to the Antarctic during World War Two, operational 1943–46. Conducted by the Admiralty on behalf of the Colonial Office, its primary objective was to strengthen British claims t ...

in 1943, to establish a presence on the continent. The chief reason was to establish solid British claims to various uninhabited islands and parts of Antarctica, reinforced by Argentine sympathies toward Germany.

Queen Maud Land

Queen Maud Land ( no, Dronning Maud Land) is a roughly region of Antarctica claimed by Norway as a dependent territory. It borders the claimed British Antarctic Territory 20° west and the Australian Antarctic Territory 45° east. In addit ...

in an attempt to create a territorial claim (New Swabia

New Swabia (Norwegian and german: Neuschwabenland) was a disputed Antarctic claim by Nazi Germany within the Norwegian territorial claim of Queen Maud Land and is now a cartographic name sometimes given to an area of Antarctica between 20°E a ...

). Led by Lieutenant James Marr, the 14-strong team left the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouzet ...

in two ships, HMS ''William Scoresby'' (a minesweeping trawler) and '' HMS Fitzroy'', on Saturday January 29, 1944. Marr had accompanied the British explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age of ...

on his final Antarctic expedition in 1921–22.

Bases were established during February near the abandoned Norwegian whaling station on Deception Island

Deception Island is an island in the South Shetland Islands close to the Antarctic Peninsula with a large and usually "safe" natural harbor, which is occasionally troubled by the underlying active volcano. This island is the caldera of an act ...

, where the Union Flag

The Union Jack, or Union Flag, is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. Although no law has been passed making the Union Flag the official national flag of the United Kingdom, it has effectively become such through precedent. ...

was hoisted in place of Argentine flags, and at Port Lockroy

Port Lockroy is a bay forming a natural harbour on the north-western shore of Wiencke Island in the Palmer Archipelago to the west of the Antarctic Peninsula. The Antarctic base with the same name, situated on Goudier Island in this bay, inc ...

(on February 11) on the coast of Graham Land

Graham Land is the portion of the Antarctic Peninsula that lies north of a line joining Cape Jeremy and Cape Agassiz. This description of Graham Land is consistent with the 1964 agreement between the British Antarctic Place-names Committee and ...

. A further base was founded at Hope Bay

Hope Bay (Spanish: ''Bahía Esperanza'') on Trinity Peninsula, is long and wide, indenting the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula and opening on Antarctic Sound. It is the site of the Argentinian Antarctic settlement Esperanza Base, established i ...

on February 13, 1945, after a failed attempt to unload stores on February 7, 1944. These bases were the first ever to be constructed on the mainland Antarctica.

The United States starting under the leadership of Admiral Richard E. Byrd

Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. (October 25, 1888 – March 11, 1957) was an American naval officer and explorer. He was a recipient of the Medal of Honor, the highest honor for valor given by the United States, and was a pioneering American aviator, p ...

constructed a series of five bases near the Bay of Whales

The Bay of Whales was a natural ice harbour, or iceport, indenting the front of the Ross Ice Shelf just north of Roosevelt Island, Antarctica. It is the southernmost point of open ocean not only of the Ross Sea, but worldwide. The Ross Sea ...

named Little America between 1929 and 1958. All of them have now drifted off to sea on icebergs.

A massive expansion in international activity followed the war. Chile organized its First Chilean Antarctic Expedition

The First Chilean Antarctic Expedition (1947–1948) was an expedition to Antarctica mounted by the Chilean government and military to enforce its territorial claims against British challenges, namely Operation Tabarin.

Among other accomplishmen ...

in 1947–48. Among other accomplishments, it brought the Chilean president Gabriel González Videla

Gabriel Enrique González Videla (; November 22, 1898 – August 22, 1980) was a Chilean politician and lawyer who served as the 24th president of Chile from 1946 to 1952. He had previously been a member of the Chamber of Deputies from 193 ...

to personally inaugurate one of its bases, thereby becoming the first head of state to set foot on the continent.Antarctica and the Arctic: the complete encyclopedia, Volume 1, by David McGonigal, Lynn Woodworth, page 98 Signy Research Station

Signy Research Station (originally Station H) is an Antarctic research base on Signy Island, run by the British Antarctic Survey.

History

Signy was first occupied in 1947 when a three-man meteorological station was established in Factory Cove ab ...

(UK) was established in 1947, Australia's Mawson Station

The Mawson Station, commonly called Mawson, is one of three permanent bases and research outposts in Antarctica managed by the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD). Mawson lies in Holme Bay in Mac. Robertson Land, East Antarctica in the Austra ...

in 1954, Dumont d'Urville Station

The Dumont d'Urville Station (french: Base antarctique Dumont-d'Urville) is a French scientific station in Antarctica on Île des Pétrels, Geologie Archipelago, archipelago of Pointe-Géologie in Adélie Land. It is named after exploration, exp ...

was the first French station in 1956. In that same year, the United States built McMurdo Station

McMurdo Station is a United States Antarctic research station on the south tip of Ross Island, which is in the New Zealand-claimed Ross Dependency on the shore of McMurdo Sound in Antarctica. It is operated by the United States through the Unit ...

and Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station

The Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station is the United States scientific research station at the South Pole of the Earth. It is the southernmost point under the jurisdiction (not sovereignty) of the United States. The station is located on the ...

, and the Soviet Union built Mirny Station

The Mirny Station (russian: Мирный, literally ''Peaceful'') is a Russian (formerly Soviet) first Antarctic science station located in Queen Mary Land, Antarctica, on the Antarctic coast of the Davis Sea.

The station is managed by the Ar ...

.

List of research stations

The United States maintains the southernmost base,Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station

The Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station is the United States scientific research station at the South Pole of the Earth. It is the southernmost point under the jurisdiction (not sovereignty) of the United States. The station is located on the ...

, and the largest base and research station in Antarctica, McMurdo Station

McMurdo Station is a United States Antarctic research station on the south tip of Ross Island, which is in the New Zealand-claimed Ross Dependency on the shore of McMurdo Sound in Antarctica. It is operated by the United States through the Unit ...

. The second-southernmost base is the Chinese Kunlun Station

Kunlun Station () is the southernmost of four Chinese research stations in Antarctica. When it is occupied during the summer, it is the second-southernmost research base in Antarctica, behind only the American Amundsen–Scott South Pole Statio ...

at 80°25′02″S during the summer season, and the Russian Vostok Station

Vostok Station (russian: :ru:Восток (антарктическая станция), ста́нция Восто́к, translit=stántsiya Vostók, , meaning "Station East") is a Russian Research stations in Antarctica, research station in ...

at 78°27′50″S during the winter season.

:''*'' Observes daylight saving time

Daylight saving time (DST), also referred to as daylight savings time or simply daylight time (United States, Canada, and Australia), and summer time (United Kingdom, European Union, and others), is the practice of advancing clocks (typicall ...

.

List of

Subantarctic

The sub-Antarctic zone is a region in the Southern Hemisphere, located immediately north of the Antarctic region. This translates roughly to a latitude of between 46° and 60° south of the Equator. The subantarctic region includes many islands ...

research stations

:''*'' Observes daylight saving time

Daylight saving time (DST), also referred to as daylight savings time or simply daylight time (United States, Canada, and Australia), and summer time (United Kingdom, European Union, and others), is the practice of advancing clocks (typicall ...

.

Map

This map shows permanent research stations only.See also

*Antarctic field camps

Many Antarctic research stations support satellite field camps which are, in general, seasonal camps. The type of field camp can vary – some are permanent structures used during the annual Antarctic summer, whereas others are little more than te ...

*Demographics of Antarctica

Antarctica has no permanent residents. It contains research stations and field camps that are staffed seasonally or year-round, and former whaling settlements. Approximately 12 nations, all signatory to the Antarctic Treaty, send personnel to per ...

*Territorial claims in Antarctica

Seven sovereign states – Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway, and the United Kingdom – have made eight territorial claims in Antarctica. These countries have tended to place their Antarctic scientific observation and st ...

*List of research stations in the Arctic

A number of governments maintain permanent research stations in the Arctic. Also known as Arctic bases, polar stations or ice stations, these bases are widely distributed across the northern polar region of Earth.

Historically few research st ...

(for analogous stations in the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

)

*List of Antarctic expeditions

This list of Antarctic expeditions is a chronological list of expeditions involving Antarctica. Although the existence of a southern continent had been hypothesized as early as the writings of Ptolemy in the 1st century AD, the South Pole was no ...

*Transport in Antarctica

Transport in Antarctica has transformed from explorers crossing the isolated remote area of Antarctica by foot to a more open era due to human technologies enabling more convenient and faster transport, predominantly by air and water, but also by ...

*Winter-over syndrome

The winter-over syndrome is a condition that occurs in individuals who "winter-over" throughout the Antarctic (or Arctic) winter, which can last seven to eight months. It has been observed in inhabitants of research stations in Antarctica, as we ...

*Human outpost

Human outposts

References

External links

Research stations

COMNAP Antarctic Facilities Map

()

Antarctic Exploration Timeline

animated map of Antarctic exploration and settlement, showing where and when Antarctic research stations were established

Antarctic Digital Database Map Viewer

SCAR {{Polar exploration Antarctica-related lists Government research Science and technology in Antarctica Antarctic research Research-related lists