Anson P.K. Safford on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anson Pacely Killen SaffordVarious sources give multiple variations for the spelling of Safford's two middle names. Among these are Peasley, Peacely, Keeler, and Killen. (c. February 14, 1830– December 15, 1891) was the third Governor of

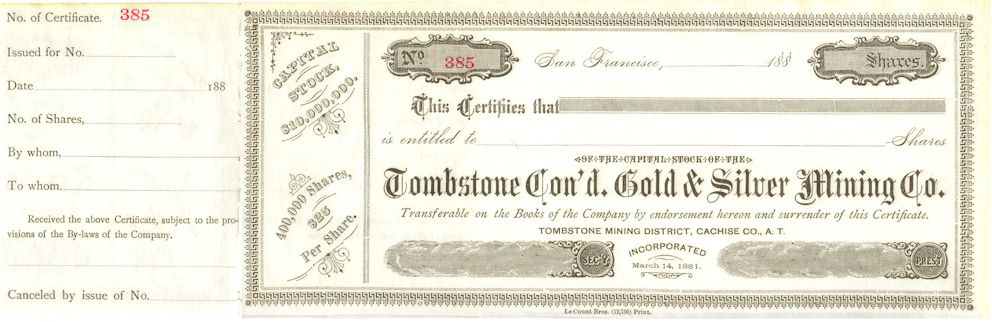

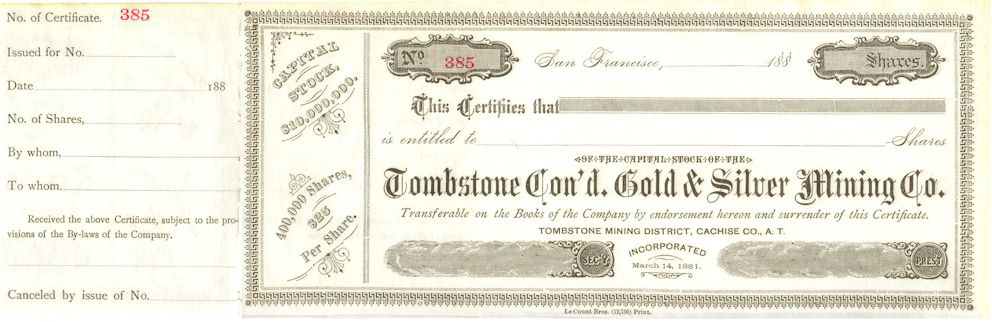

In early March 1881, the Tombstone Mining and Milling Company was sold to capitalists from Philadelphia, and Safford became president of the new Tombstone Gold and Silver Milling and Mining Company with Richard Gird was superintendent. Ed and Al Schieffelin soon sold their one-third ownership in the Tough Nut for $1 million and moved on, although Al remained in Tombstone for sometime longer. Gird later sold off his one-third interest for $1 million, doubling what the Schieffelins had been paid. In 1880, Safford was a delegate to the

In early March 1881, the Tombstone Mining and Milling Company was sold to capitalists from Philadelphia, and Safford became president of the new Tombstone Gold and Silver Milling and Mining Company with Richard Gird was superintendent. Ed and Al Schieffelin soon sold their one-third ownership in the Tough Nut for $1 million and moved on, although Al remained in Tombstone for sometime longer. Gird later sold off his one-third interest for $1 million, doubling what the Schieffelins had been paid. In 1880, Safford was a delegate to the

Arizona Territory

The Territory of Arizona (also known as Arizona Territory) was a territory of the United States that existed from February 24, 1863, until February 14, 1912, when the remaining extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of ...

. He was also a member of the California State Assembly

The California State Assembly is the lower house of the California State Legislature, the upper house being the California State Senate. The Assembly convenes, along with the State Senate, at the California State Capitol in Sacramento.

The A ...

from 1857–1858. Affectionately known as the "Little Governor" due to his stature, he was also Arizona's longest-serving territorial governor. His work to create a public education

State schools (in England, Wales, Australia and New Zealand) or public schools (Scottish English and North American English) are generally primary or secondary schools that educate all students without charge. They are funded in whole or in pa ...

system earned him the name "Father of the Arizona Public Schools". Safford is additionally known for granting himself a divorce.

Background

Safford was born to Joseph Warren and Diantha P. (Little) Safford in Hyde Park, Vermont, on February 14 of either 1828 or 1830. When he was eight, his family moved toCrete, Illinois

Crete is a village in Will County, Illinois, United States, a south suburb of Chicago. The population was 8,259 at the 2010 census. Originally named Wood's Corner, it was founded in 1836 by Vermonters Dyantha and Willard Wood.

Geography

Crete i ...

, where they farmed. Safford was largely self-educated, attending only five quarters at a county school followed later by six months at a different school. His father died in 1848 and his mother in 1849. Safford left the family farm in March 1850 as part of the California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California fro ...

.

After his arrival in California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, Safford began working a claim in Placer County

Placer County ( ; Spanish for "sand deposit"), officially the County of Placer, is a county in the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 404,739. The county seat is Auburn.

Placer County is included in the Great ...

that produced from five to twenty dollars per day. His leisure time was spent reading from a set of books he had purchased to further his education. In 1854 he moved to a new claim and in 1855 was a Democratic party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

nominee for a seat in the California State Assembly

The California State Assembly is the lower house of the California State Legislature, the upper house being the California State Senate. The Assembly convenes, along with the State Senate, at the California State Capitol in Sacramento.

The A ...

, losing his race to a Know Nothing

The Know Nothing party was a nativist political party and movement in the United States in the mid-1850s. The party was officially known as the "Native American Party" prior to 1855 and thereafter, it was simply known as the "American Party". ...

candidate. Safford won a seat as an assemblyman in 1857 and was reelected in 1859.

Following his time in the state legislature, Safford moved to San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

where he operated an earthworks

Earthworks may refer to:

Construction

*Earthworks (archaeology), human-made constructions that modify the land contour

* Earthworks (engineering), civil engineering works created by moving or processing quantities of soil

*Earthworks (military), m ...

business. When the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

broke out, he changed his political affiliation to the Unionist party and later became a Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

. Safford moved to Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. N ...

in early 1862 and was elected county commissioner

A county commission (or a board of county commissioners) is a group of elected officials (county commissioners) collectively charged with administering the county government in some states of the United States; such commissions usually comprise ...

for Humboldt County in November 1862. After a month in office, he resigned as commissioner and later served as a mining recorder and county recorder

Recorder of deeds or deeds registry is a government office tasked with maintaining public records and documents, especially records relating to real estate ownership that provide persons other than the owner of a property with real rights over ...

. Safford was secretary of the Nevada constitutional convention in November 1863 and president of Nevada's first Republican state convention. To add to his cultural experience, Safford took a two-year trip to Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

and then returned to Nevada. He turned down a nomination to the US House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they c ...

before being appointed surveyor-general of Nevada by President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

in March 1867. Safford served as surveyor-general for two years before health issues forced him to resign.

Safford married Jenny (or Jennie) L. Tracy in Tucson, Arizona

, "(at the) base of the black ill

, nicknames = "The Old Pueblo", "Optics Valley", "America's biggest small town"

, image_map =

, mapsize = 260px

, map_caption = Interactive map ...

, on July 24, 1869. The couple had a son who was born July 2, 1870, and died August 28, 1871. The couple quickly became estranged and their dispute escalated to the point where Jenny Safford had notices printed claiming her husband had engaged in infidelity and was suffering from a venereal disease

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the older term venereal diseases, are infections that are spread by sexual activity, especially vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and oral se ...

. This marriage ended when Arizona's territorial legislature passed a bill granting a divorce to the couple. Governor Safford signing the bill into law in January 1873 and his ex-wife remarried on February 24, 1873. Safford's second marriage was to Margarita Grijalva on December 12, 1878. The couple had one daughter before Margarita Safford died in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

on January 7, 1880. Safford's third marriage was to Soledad Bonillas, sister of Ignacio Bonillas

Ignacio Bonillas Fraijo (1 February 1858 – 23 June 1942) was a Mexican diplomat. He was a Mexican ambassador to the United States and held a degree in mine engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He was tapped by Pres ...

, on September 10, 1881. During his life, Safford adopted two children.

Governorship

On March 13, 1869, the Nevada Congressional delegation of Thomas Fitch, James W. Nye, andWilliam M. Stewart

William Morris Stewart (August 9, 1827April 23, 1909) was an American lawyer and politician. In 1964, he was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

Personal

Stewart was born in Wayne Count ...

petitioned President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

to nominate Safford as Governor of Arizona Territory. This nomination was supported by Arizona's Coles Bashford

Coles Bashford (January 24, 1816April 25, 1878) was an American lawyer and politician who became the fifth governor of Wisconsin, and one of the founders of the U.S. Republican Party. His one term as governor ended in a bribery scandal that end ...

, John N. Goodwin

John Noble Goodwin (October 18, 1824 – April 29, 1887) was a United States attorney and politician who served as the first Governor of Arizona Territory. He was also a Congressman from Maine and served as Arizona Territory's delegate to the Un ...

, and Richard C. McCormick along with political figures from California. Safford was nominated on April 3, 1869, commissioned April 9, 1869, and sworn into office on July 9, 1869. His second term began in April 1873 and he declined a third term.

The Safford administration immediately faced the problem of hostile Indians. To counter this threat he called for the creation of volunteer militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

and worked with Territorial Delegate McCormick to have General George Stoneman

George Stoneman Jr. (August 8, 1822 – September 5, 1894) was a United States Army cavalry officer and politician who served as the fifteenth Governor of California from 1883 to 1887. He was trained at West Point, where his roommate was Stonewall ...

replaced by George Crook

George R. Crook (September 8, 1828 – March 21, 1890) was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook ''Nantan ...

in June 1871. Safford was also forced to assign a military force to guard the road between Gila Bend

Gila Bend (; O'odham: Hila Wi:n), founded in 1872, is a town in Maricopa County, Arizona, United States. The town is named for an approximately 90-degree bend in the Gila River, which is near the community's current location. As of the 2020 cen ...

and Fort Yuma

Fort Yuma was a fort in California located in Imperial County, across the Colorado River from Yuma, Arizona. It was on the Butterfield Overland Mail route from 1858 until 1861 and was abandoned May 16, 1883, and transferred to the Department of ...

from Mexican outlaw

An outlaw, in its original and legal meaning, is a person declared as outside the protection of the law. In pre-modern societies, all legal protection was withdrawn from the criminal, so that anyone was legally empowered to persecute or kill them ...

s. Other efforts to combat lawlessness included the governor petitioning the territorial legislature to make highway robbery

Robbery is the crime of taking or attempting to take anything of value by force, threat of force, or by use of fear. According to common law, robbery is defined as taking the property of another, with the intent to permanently deprive the perso ...

a capital offense

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

and the building of a territorial prison. As a result of these efforts Indian hostilities were largely eliminated, with only occasional outbreaks, and enough order was instilled into the territory to allow for ranching activities to move to Arizona.

Safford's passion while in office was the creation of a public school system. This effort was initially opposed by the legislature, but the governor was able to win passage of a new property tax

A property tax or millage rate is an ad valorem tax on the value of a property.In the OECD classification scheme, tax on property includes "taxes on immovable property or net wealth, taxes on the change of ownership of property through inheri ...

on February 17, 1871, to finance creation and operation of schools. As ''ex officio'' superintendent of public instruction, the governor corresponded with educators across the nation and even used his personal funds to help build schools or bring new teachers to Arizona. Arizona's first public school opened during March 1872 in Tucson

, "(at the) base of the black ill

, nicknames = "The Old Pueblo", "Optics Valley", "America's biggest small town"

, image_map =

, mapsize = 260px

, map_caption = Interactive map ...

. The one room adobe structure had a single teacher and, at its peak, 138 students. Other schools were built throughout the territory over the next few years. During his address to the territorial legislature in January 1877, Safford was pleased to report that at least 1450 of the 2955 children counted in the May 1876 census could read and write.

After office

After leaving office Safford opened one of Arizona's first banks, with offices in Tucson and Tombstone. He wasadmitted to the bar

An admission to practice law is acquired when a lawyer receives a license to practice law. In jurisdictions with two types of lawyer, as with barristers and solicitors, barristers must gain admission to the bar whereas for solicitors there are dist ...

in January 1875 but did not work as an attorney. Instead, with the assistance of his friend, John S. Vosburg, helped finance several mines. When the first claims were filed in Tombstone, the initial settlement of tents and cabins was located at Watervale near the Lucky Cuss mine. Safford offered financial backing for a cut of the Lucky Cuss mining claim, and Ed Schieffelin

Edward Lawrence Schieffelin (1847–1897) was an U.S. Army Indian Scouts, Indian scout and prospecting, prospector who discovered silver in the Arizona Territory, which led to the founding of Tombstone, Arizona. He partnered with his brother Al an ...

, his brother Al, and their partner Richard Gird formed the Tombstone Mining and Milling Company and with Safford's backing built the first stamping mill. When the mill was built, the town site was moved to Goose Flats, a mesa

A mesa is an isolated, flat-topped elevation, ridge or hill, which is bounded from all sides by steep escarpments and stands distinctly above a surrounding plain. Mesas characteristically consist of flat-lying soft sedimentary rocks capped by ...

above the Toughnut above sea level and large enough to hold a growing town.

In early March 1881, the Tombstone Mining and Milling Company was sold to capitalists from Philadelphia, and Safford became president of the new Tombstone Gold and Silver Milling and Mining Company with Richard Gird was superintendent. Ed and Al Schieffelin soon sold their one-third ownership in the Tough Nut for $1 million and moved on, although Al remained in Tombstone for sometime longer. Gird later sold off his one-third interest for $1 million, doubling what the Schieffelins had been paid. In 1880, Safford was a delegate to the

In early March 1881, the Tombstone Mining and Milling Company was sold to capitalists from Philadelphia, and Safford became president of the new Tombstone Gold and Silver Milling and Mining Company with Richard Gird was superintendent. Ed and Al Schieffelin soon sold their one-third ownership in the Tough Nut for $1 million and moved on, although Al remained in Tombstone for sometime longer. Gird later sold off his one-third interest for $1 million, doubling what the Schieffelins had been paid. In 1880, Safford was a delegate to the Republican National Convention

The Republican National Convention (RNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1856 by the United States Republican Party. They are administered by the Republican National Committee. The goal of the Repu ...

.

In the early 1880s, Safford sold his business interests for roughly $140,000 and moved to Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

and then New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. By 1882 Safford had moved to Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

and become involved with building the new community of Tarpon Springs

Tarpon Springs is a city in Pinellas County, Florida, United States. The population was 23,484 at the 2010 census. Tarpon Springs has the highest percentage of Greek Americans of any city in the US. Downtown Tarpon Springs has long been a focal po ...

. He was a candidate for Arizona Territorial Governor again in 1889, with support coming from Matthew Quay

Matthew Stanley "Matt" Quay (September 30, 1833May 28, 1904) was an American politician of the Republican Party who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate from 1887 until 1899 and from 1901 until his death in 1904. Quay's control ...

, Leland Stanford

Amasa Leland Stanford (March 9, 1824June 21, 1893) was an American industrialist and politician. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the 8th governor of California from 1862 to 1863 and represented California in the United States Se ...

, and William M. Stewart, but was not nominated. Safford's later years were spent in Florida with his family and sister, Mary Jane Safford-Blake. He died on December 15, 1891, in Tarpon Springs and was buried at Cycadia Cemetery.

See also

*Safford House

The Safford House is a historic home in Tarpon Springs, Florida. On October 16, 1974, it was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. The house is named for its original owner, Anson P.K. Safford.

The city of Tarpon Springs o ...

Footnotes

References

Bibliography

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Safford, Anson P. K. American surveyors Arizona pioneers Governors of Arizona Territory Members of the California State Assembly 1830 births 1891 deaths Arizona Republicans California Democrats Florida Republicans Nevada Republicans Safford, Arizona 19th-century American politicians People from Hyde Park, Vermont People from Crete, Illinois