Annie Meinertzhagen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

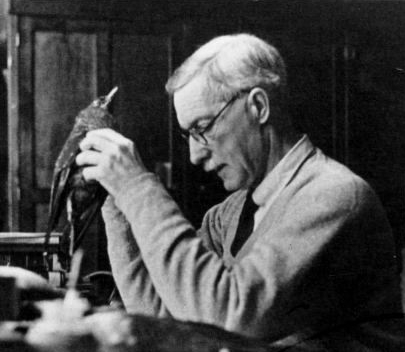

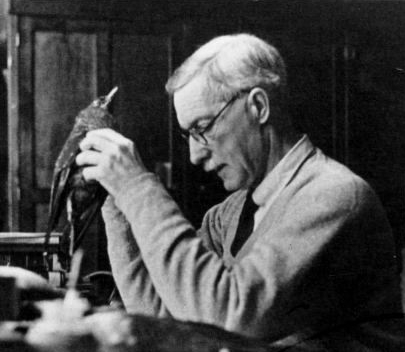

Annie Meinertzhagen (2 June 1889 – 6 July 1928) was a Scottish

In March 1921, she married British soldier, intelligence officer and ornithologist

In March 1921, she married British soldier, intelligence officer and ornithologist

ornithologist

Ornithology is a branch of zoology that concerns the "methodological study and consequent knowledge of birds with all that relates to them." Several aspects of ornithology differ from related disciplines, due partly to the high visibility and th ...

who contributed to studies on British birds, most significantly the moulting patterns in ducks and waders. She married fellow ornithologist Richard Meinertzhagen

Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, CBE, DSO (3 March 1878 – 17 June 1967) was a British soldier, intelligence officer, and ornithologist. He had a decorated military career spanning Africa and the Middle East. He was credited with creating and e ...

in 1921 and died from a gunshot fired under suspicious circumstances.

Early years

Born Anne Constance Jackson, her parents were Major Randle Jackson and Emily V. Baxter of Swordale, a village in easternRoss-shire

Ross-shire (; gd, Siorrachd Rois) is a historic county in the Scottish Highlands. The county borders Sutherland to the north and Inverness-shire to the south, as well as having a complex border with Cromartyshire – a county consisting of ...

in the Scottish Highlands

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Sco ...

. Mrs Jackson was the daughter of Edward Baxter of Kincaldrum, Angus. Anne developed an early interest in natural history, especially in bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

s. With her younger sister Dorothy, who was to become an entomologist

Entomology () is the scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such as arach ...

, she studied zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the Animal, animal kingdom, including the anatomy, structure, embryology, evolution, Biological clas ...

for three years at the Imperial College of Science

Imperial College London (legally Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine) is a public research university in London, United Kingdom. Its history began with Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria, who developed his vision for a cu ...

in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

under Ernest MacBride

Ernest William MacBride FRS (12 December 1866, in Belfast – 17 November 1940, in Alton, Hampshire) was a British/Irish marine biologist, one of the last supporters of Lamarckian evolution.

Life

MacBride was the eldest of the five children o ...

. In 1915, she published a paper with MacBride in the Proceedings of the Royal Society

''Proceedings of the Royal Society'' is the main research journal of the Royal Society. The journal began in 1831 and was split into two series in 1905:

* Series A: for papers in physical sciences and mathematics.

* Series B: for papers in life s ...

on the inheritance of colour in the stick insect ''Carausius morosus

''Carausius morosus'' (the 'common', 'Indian' or 'laboratory' stick insect) is a species of Phasmatodea (phasmid) often kept as pets by schools and individuals. Culture stocks originate from a collection from Tamil Nadu, India. Like the majorit ...

''.

Much of her early ornithological work occurred while she was based in Swordale, in Ross and Cromarty

Ross and Cromarty ( gd, Ros agus Cromba), sometimes referred to as Ross-shire and Cromartyshire, is a variously defined area in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. There is a registration county and a lieutenancy area in current use, the latt ...

, and along the firth

Firth is a word in the English and Scots languages used to denote various coastal waters in the United Kingdom, predominantly within Scotland. In the Northern Isles, it more usually refers to a smaller inlet. It is linguistically cognate to ''fj ...

s of Cromarty

Cromarty (; gd, Cromba, ) is a town, civil parish and former royal burgh in Ross and Cromarty, in the Highland area of Scotland. Situated at the tip of the Black Isle on the southern shore of the mouth of Cromarty Firth, it is seaward from In ...

and Dornoch

Dornoch (; gd, Dòrnach ; sco, Dornach) is a town, seaside resort, parish and former royal burgh in the county of Sutherland in the Highlands of Scotland. It lies on the north shore of the Dornoch Firth, near to where it opens into the Moray ...

she began publishing papers on the local birdlife in 1909. She took an interest in bird migration

Bird migration is the regular seasonal movement, often north and south along a flyway, between breeding and wintering grounds. Many species of bird migrate. Migration carries high costs in predation and mortality, including from hunting by ...

and corresponded with lighthouse keeper

A lighthouse keeper or lightkeeper is a person responsible for tending and caring for a lighthouse, particularly the light and lens in the days when oil lamps and clockwork mechanisms were used. Lighthouse keepers were sometimes referred to as ...

s who sent her specimens of rarities. She collected the first Scottish autumn specimens of the yellow-browed warbler

The yellow-browed warbler (''Phylloscopus inornatus'') is a leaf warbler (family Phylloscopidae) which breeds in the east Palearctic. This warbler is strongly migratory and winters mainly in tropical South Asia and South-east Asia, but also ...

and was the first ornithologist to demonstrate that the Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

ic race of the common redshank

The common redshank or simply redshank (''Tringa totanus'') is a Eurasian wader in the large family Scolopacidae.

Taxonomy

The common redshank was formally described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of his ...

(''Tringa totanus robusta'') visits Britain. She often accompanied her cousin, Evelyn V. Baxter, during ornithological research.

Marriage

In March 1921, she married British soldier, intelligence officer and ornithologist

In March 1921, she married British soldier, intelligence officer and ornithologist Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

Richard Meinertzhagen

Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, CBE, DSO (3 March 1878 – 17 June 1967) was a British soldier, intelligence officer, and ornithologist. He had a decorated military career spanning Africa and the Middle East. He was credited with creating and e ...

. She spent part of her honeymoon

A honeymoon is a vacation taken by newlyweds immediately after their wedding, to celebrate their marriage. Today, honeymoons are often celebrated in destinations considered exotic or romantic. In a similar context, it may also refer to the phase ...

in research at Walter Rothschild

Lionel Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild, Baron de Rothschild, (8 February 1868 – 27 August 1937) was a British banker, politician, zoologist and soldier, who was a member of the Rothschild family. As a Zionist leader, he was present ...

's ornithological museum at Tring

Tring is a market town and civil parish in the Borough of Dacorum, Hertfordshire, England. It is situated in a gap passing through the Chiltern Hills, classed as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, from Central London. Tring is linked to ...

.

In the further course of her ornithological studies she travelled to Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

in 1921, to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

and Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

in 1923, to Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

in 1925, and to India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

in the winter of 1925–26, when she joined her husband in an expedition to Sikkim

Sikkim (; ) is a state in Northeastern India. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China in the north and northeast, Bhutan in the east, Province No. 1 of Nepal in the west and West Bengal in the south. Sikkim is also close to the Siligur ...

and southern Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

hunting birds and mammals in the Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 100 ...

. She also gave birth to three children, Anne (born 1921), Daniel (born 1925) and Randle (born 1928).

Annie Constance Meinertzhagen left £113,466 (net personalty

Personal property is property that is movable. In common law systems, personal property may also be called chattels or personalty. In civil law (legal system), civil law systems, personal property is often called movable property or movables— ...

£18,733) in her will to her husband if he should remain her widower and if he re-married he was to get an annuity of £1,200 and interest in their London home for life.

Death

Annie Meinertzhagen died at her estate at Swordale on 6 July 1928, just over three months after the birth of her third child, in an apparent shooting accident in the presence of her husband. The circumstances of her death were controversial, though no inquest or enquiry took place. Richard Meinertzhagen's diary entry for 1 August 1928 reads:”I have not written up my story for some weeks not because I have had nothing to say but because my heart has been too full of sorrow my soul too overwhelmed with unhappiness. My darling Annie died on July 6th as a result of a terrible accident at Swordale. We had been practising with my revolver and had just finished when I went to bring back the target. I heard a shot behind me and saw my darling fall with a bullet through her head.”

Brian Garfield

Brian Francis Wynne Garfield (January 26, 1939 – December 29, 2018) was an Edgar Award-winning American novelist, historian and screenwriter. A Pulitzer Prize finalist, he wrote his first published book at the age of eighteen. Garfield went on ...

comments, in his exposé of Richard Meinertzhagen's life and character:

”To those who believe that Annie’s death was no accident, the circumstantial evidence seems persuasive. The path of the bullet would seem to create doubt as to whether she could have inflicted the wound on herself. RM was at least a foot taller than his wife, so a downward shot through her head and spine – especially if she were leaning forward a bit – could have been fired much more readily by him than by her.

”It is argued that Annie would not likely have shot herself by accident. She was an expert with firearms, having grown up with them in the landed hunting set and having spent years hunting birds all over the world and providing specimens to the leading museums".

”Those who believe she was murdered point out that if ever in RM’s long and bloody career there was a smoking gun, this was that case – literally, with its bullet driven through Annie’s head and spine at point-blank range. They cite the standard homicide trinity; method, opportunity, and motive. Annie was shot to death at close range; her husband was the only witness; she died under suspicious circumstances at a time when her death was very much to his benefit because, they point out, it kept her from exposing his bird thefts, it freed him to carry on with his pubescent cousins, and it left him with a large income for life".

Publications

Annie Meinertzhagen's ornithological research was mainly concerned withwader

245px, A flock of Dunlins and Red knots">Red_knot.html" ;"title="Dunlins and Red knot">Dunlins and Red knots

Waders or shorebirds are birds of the order Charadriiformes commonly found wikt:wade#Etymology 1, wading along shorelines and mudflat ...

s and duck

Duck is the common name for numerous species of waterfowl in the family Anatidae. Ducks are generally smaller and shorter-necked than swans and geese, which are members of the same family. Divided among several subfamilies, they are a form t ...

s. Under her maiden name she authored a series of articles on the moults of British ducks and waders which formed the basis of her contributions on their plumages to Witherby's ''Practical Handbook of British Birds'' (1919–1924). Under her married name she made several important contributions to the ''Ibis'', including review papers on the genus ''Burhinus

''Burhinus'' is a genus of birds in the family Burhinidae. This family also contains the genus ''Esacus''.del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J (1996) ''Handbook of the Birds of the World'', ''vol 3.'' Lynx, Barcelona The genus name ''Burhinus'' com ...

'' in 1924, the subfamily Scolopacinae in 1926, and the family Cursoridae in 1927.

Recognition

* 1915 – Honorary Lady Member of theBritish Ornithologists' Union

The British Ornithologists' Union (BOU) aims to encourage the study of birds ("ornithology") and around the world, in order to understand their biology and to aid their conservation. The BOU was founded in 1858 by Professor Alfred Newton, Henry ...

* 1919 – Corresponding Member of the American Ornithologists' Union

The American Ornithological Society (AOS) is an ornithological organization based in the United States. The society was formed in October 2016 by the merger of the American Ornithologists' Union (AOU) and the Cooper Ornithological Society. Its m ...

She is honoured in the subspecific name of the Antipodes snipe

The Antipodes snipe (''Coenocorypha aucklandica meinertzhagenae''), also known as the Antipodes Island snipe, is an isolated subspecies of the Subantarctic snipe that is endemic to the Antipodes Islands, a subantarctic island group south of New ...

(''Coenocorypha aucklandica meinertzhagenae''), described by Walter Rothschild in 1927. The subspecies '' Anthus cinnamomenus annae'' and ''Ammomanes deserti annae'' are also named in her honour.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Meinertzhagen, Annie 1889 births 1928 deaths British ornithologists Women ornithologists Firearm accident victims Deaths by firearm in Scotland Zoological collectors 20th-century British women scientists 20th-century British zoologists Accidental deaths in Scotland