Anne Greene on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anne Greene (1659) was an English domestic servant who was accused of committing

Anne Greene (1659) was an English domestic servant who was accused of committing

Greene was born around 1628 in Steeple Barton, Oxfordshire. In her early adulthood, she worked as a scullery maid in the house of Sir Thomas Read, a justice of the peace who lived in nearby

Greene was born around 1628 in Steeple Barton, Oxfordshire. In her early adulthood, she worked as a scullery maid in the house of Sir Thomas Read, a justice of the peace who lived in nearby

Anne Greene (1659) was an English domestic servant who was accused of committing

Anne Greene (1659) was an English domestic servant who was accused of committing infanticide

Infanticide (or infant homicide) is the intentional killing of infants or offspring. Infanticide was a widespread practice throughout human history that was mainly used to dispose of unwanted children, its main purpose is the prevention of resou ...

in 1650. She survived her attempted execution and was revived by physicians from the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the world's second-oldest university in contin ...

.

Trial and punishment

Greene was born around 1628 in Steeple Barton, Oxfordshire. In her early adulthood, she worked as a scullery maid in the house of Sir Thomas Read, a justice of the peace who lived in nearby

Greene was born around 1628 in Steeple Barton, Oxfordshire. In her early adulthood, she worked as a scullery maid in the house of Sir Thomas Read, a justice of the peace who lived in nearby Duns Tew

Duns Tew is an English village and civil parish about south of Banbury in Oxfordshire. The 2011 Census recorded the parish's population as 478. With nearby Great Tew and Little Tew, Duns Tew is one of the three villages known collectively a ...

. She later claimed that in 1650 when she was a 22-year-old servant, she was seduced by Sir Thomas's grandson, Geoffrey Read, who was 16 or 17 years old.

She became pregnant, though she later claimed that she was not aware of her pregnancy until she miscarried in the privy after seventeen weeks. She tried to conceal the remains of the fetus but was discovered and suspected of infanticide. Sir Thomas prosecuted Greene under the "Concealment of Birth of Bastards" Act 1624, under which there was a legal presumption that a woman who concealed the death of her illegitimate child had murdered it.

A midwife testified that the fetus was too underdeveloped to have ever been alive, and several servants who worked with Greene testified that she had experienced "issues" for approximately one month before her miscarriage, which began after she laboured turning malt". In spite of the testimony, Greene was found guilty of murder and was hanged

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging in ...

at Oxford Castle

Oxford Castle is a large, partly ruined medieval castle on the western side of central Oxford in Oxfordshire, England. Most of the original moated, wooden motte and bailey castle was replaced in stone in the late 12th or early 13th century and ...

on 14 December 1650. At her own request, several of her friends pulled her swinging body and a soldier struck her four or five times with the butt of his musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket graduall ...

to expedite her death. After half an hour, everyone believed her dead, so she was cut down and given to University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the world's second-oldest university in contin ...

physicians William Petty

Sir William Petty FRS (26 May 1623 – 16 December 1687) was an English economist, physician, scientist and philosopher. He first became prominent serving Oliver Cromwell and the Commonwealth in Ireland. He developed efficient methods to su ...

and Thomas Willis

Thomas Willis FRS (27 January 1621 – 11 November 1675) was an English doctor who played an important part in the history of anatomy, neurology and psychiatry, and was a founding member of the Royal Society.

Life

Willis was born on his pare ...

for dissection.

Recovery

The physicians opened Greene's coffin the following day and discovered that she had a faint pulse and was weakly breathing. Petty and Willis sought the help of their Oxford colleagues Ralph Bathurst and Henry Clerke. The group of physicians tried many remedies to revive Greene, including pouring hot cordial down her throat, rubbing her limbs and extremities,bloodletting

Bloodletting (or blood-letting) is the withdrawal of blood from a patient to prevent or cure illness and disease. Bloodletting, whether by a physician or by leeches, was based on an ancient system of medicine in which blood and other bodily flu ...

, applying a poultice

A poultice, also called a cataplasm, is a soft moist mass, often heated and medicated, that is spread on cloth and placed over the skin to treat an aching, inflamed, or painful part of the body. It can be used on wounds, such as cuts.

'Poultice ...

to her breasts, and having a Tobacco smoke enema. The physicians then placed her in a warm bed with another woman, who rubbed her and kept her warm. Greene began to recover quickly, beginning to speak after twelve to fourteen hours of treatment and eating solid food after four days. Within one month she had fully recovered, aside from amnesia

Amnesia is a deficit in memory caused by brain damage or disease,Gazzaniga, M., Ivry, R., & Mangun, G. (2009) Cognitive Neuroscience: The biology of the mind. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. but it can also be caused temporarily by the use ...

about the time surrounding her execution.

The authorities granted Greene a reprieve from execution while she recovered and ultimately pardoned her, believing that the hand of God had saved her, demonstrating her innocence. Furthermore, one pamphleteer notes that Sir Thomas Read died three days after Greene's execution, so there was no prosecutor to object to the pardon. However, another pamphleteer writes that her recovery "moved some of her enemies to wrath and indignation, insomuch that a great man amongst the rest, moved to have her again carried to the place of execution, to be hanged up by the neck, contrary to all Law, reason and justice; but some honest Souldiers then present seemed to be very much discontent thereat" and intervened on Greene's behalf.

After her recovery, Greene went to stay with friends in the country, taking the coffin with her. She married, had three children and died in 1659.

Cultural significance

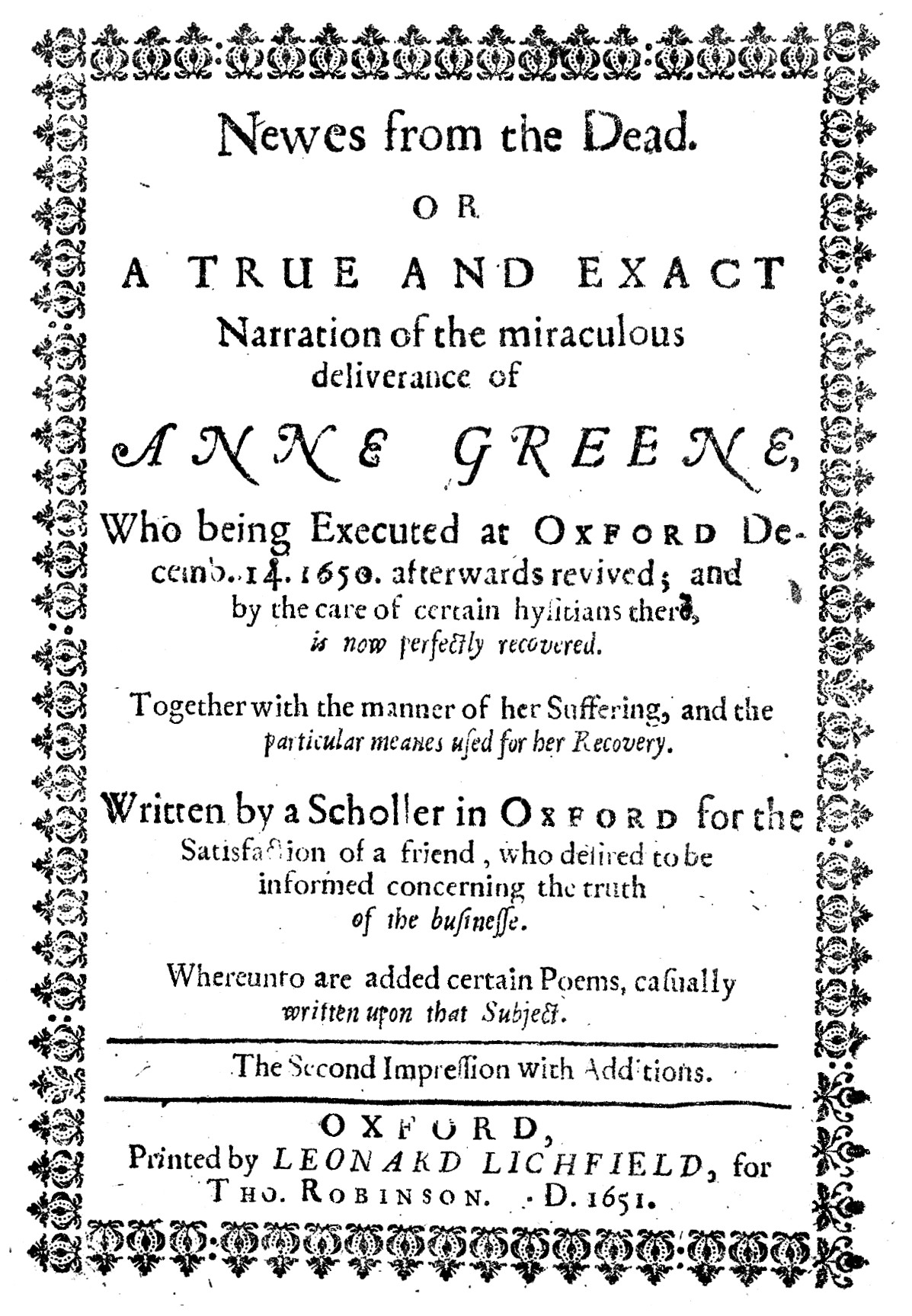

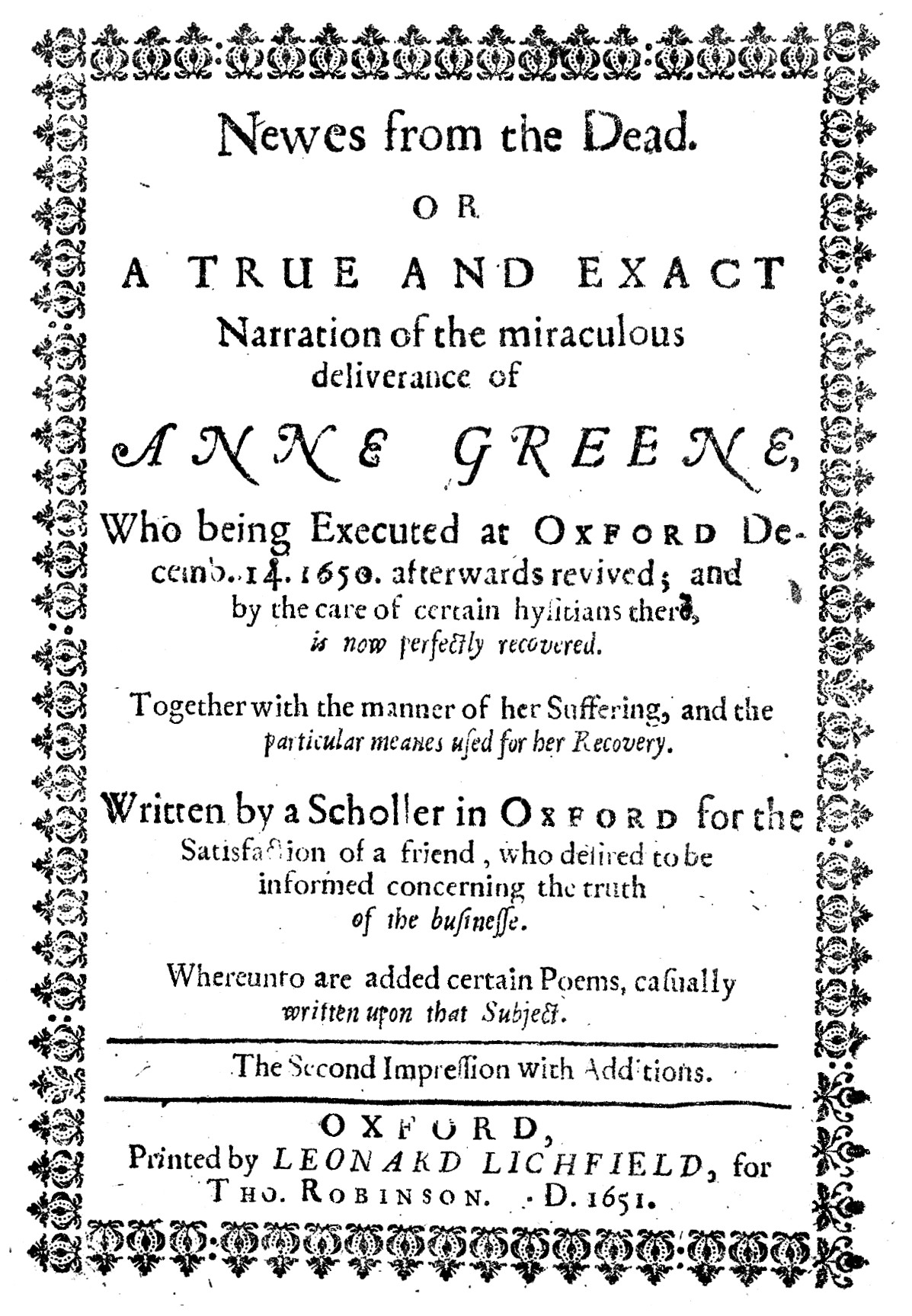

The event inspired two 17th-century pamphlets. The first, by W. Burdet, was entitled ''A Wonder of Wonders'' (Oxford, 1651) in its first edition and ''A Declaration from Oxford, of Anne Greene'' in its second edition. Burdet's pamphlets portray the event in miraculous, metaphysical terms. In 1651, Richard Watkins also published a pamphlet containing a sober, medically accurate prose account of the event and poems inspired by it, entitled ''Newes from the Dead'' (Oxford: Leonard Lichfield, 1651). The poems, of which there were 25 in various languages, included a set of English verses byChristopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (; – ) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 churc ...

, who was at that time a gentleman-commoner (a student who paid all fees in advance) of Wadham College

Wadham College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It is located in the centre of Oxford, at the intersection of Broad Street and Parks Road.

Wadham College was founded in 1610 by Dorothy ...

.

Greene's story was also mentioned in the 1659 English edition of Denis Pétau

Denis Pétau (21 August 158311 December 1652), also known as Dionysius Petavius, was a French Jesuit theologian.

Life

Pétau was born at Orléans, where he had his initial education; he then attended the University of Paris, where he successfully ...

's ''The History of the World'' and in Robert Plot

Robert Plot (13 December 1640 – 30 April 1696) was an English naturalist, first Professor of Chemistry at the University of Oxford, and the first keeper of the Ashmolean Museum.

Early life and education

Born in Borden, Kent to parents Ro ...

's 1677 ''The Natural History of Oxfordshire''. Plot's book is the first account known to have mentioned Greene's later marriage and the year of her death.

References

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Greene, Anne Execution survivors Murder in 1650 People from Oxfordshire Women who experienced pregnancy loss 1628 births 1659 deaths 17th-century English women 17th-century executions by England