Anna Kulischov on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anna Kuliscioff (; rus, Анна Кулишёва, , ˈanːə kʊlʲɪˈʂovə; born Anna Moiseyevna Rozenshtein, ; 9 January 1857 – 27 December 1925) was a Russian-Italian revolutionary of Jewish origin, a prominent

In April 1877, using a false passport, she left Russia and moved to Paris, where she became a member of a small anarchist group which, following

In April 1877, using a false passport, she left Russia and moved to Paris, where she became a member of a small anarchist group which, following  In 1912 Giovanni Giolitti's government rejected the opportunity to enfranchise women by introducing a law which granted the vote only to males, even illiterate ones, despite the fact that illiteracy was cited as among the reasons for not extending the vote to women. For Anna Kuliscioff this affair begins a dark period of discouragement and a sense of abandonment. In her relationship with Turati, political dissensions mix with personal issues, disturbing their quiet life. The last years of Kuliscioff's life were marked by much bitterness, many health problems, splits within the

In 1912 Giovanni Giolitti's government rejected the opportunity to enfranchise women by introducing a law which granted the vote only to males, even illiterate ones, despite the fact that illiteracy was cited as among the reasons for not extending the vote to women. For Anna Kuliscioff this affair begins a dark period of discouragement and a sense of abandonment. In her relationship with Turati, political dissensions mix with personal issues, disturbing their quiet life. The last years of Kuliscioff's life were marked by much bitterness, many health problems, splits within the

Because of her early lack of political commitment, Kuliscioff initially devoted herself to university studies. In 1882 she was forced to move to Switzerland where she enrolled in the faculty of medicine. Medicine satisfied her need to withdraw into an individual dimension and satisfied her aspiration for a social mission. Because of the long time spent in prison, she had contracted tuberculosis and milder climates were recommended. Thus she moved, with her daughter Andreina Costa, to

Because of her early lack of political commitment, Kuliscioff initially devoted herself to university studies. In 1882 she was forced to move to Switzerland where she enrolled in the faculty of medicine. Medicine satisfied her need to withdraw into an individual dimension and satisfied her aspiration for a social mission. Because of the long time spent in prison, she had contracted tuberculosis and milder climates were recommended. Thus she moved, with her daughter Andreina Costa, to  After completing her graduation thesis, she returned to the

After completing her graduation thesis, she returned to the  After both her academic career and that of a hospital doctor, she began her career as a "''doctor of the poor''" in via San Pietro all'Olmo 18. She offered free medical assistance to poor women. The profession of doctor of the poor forced her to be a spectator of the miserable living conditions of the Milan workers. She wanted to intervene politically in this field. Becoming a "doctor of the poor" appeared to her as a sort of force of will. She was truly admired for her work; her daily visits were expected as a blessing, in fact it was not a visit from a doctor, it was something more. Anna Kuliscioff was considered a comforter, a friend, trustworthy woman of those who suffered and their beloved. Her patients described her as a woman who was able to penetrate the depths of souls. She treated the poor people with affectionate familiarity. Kuliscioff did not dedicate her care only to the poor, in fact, even the ladies of the

After both her academic career and that of a hospital doctor, she began her career as a "''doctor of the poor''" in via San Pietro all'Olmo 18. She offered free medical assistance to poor women. The profession of doctor of the poor forced her to be a spectator of the miserable living conditions of the Milan workers. She wanted to intervene politically in this field. Becoming a "doctor of the poor" appeared to her as a sort of force of will. She was truly admired for her work; her daily visits were expected as a blessing, in fact it was not a visit from a doctor, it was something more. Anna Kuliscioff was considered a comforter, a friend, trustworthy woman of those who suffered and their beloved. Her patients described her as a woman who was able to penetrate the depths of souls. She treated the poor people with affectionate familiarity. Kuliscioff did not dedicate her care only to the poor, in fact, even the ladies of the

Anna Kuliscioff. La signora del socialismo italiano

'. Editori Riuniti Univ. Press, 2013 (In Italian) * Damiani Franco and Rodriguez Fabio (edited by), ''Anna Kuliscioff: immagini, scritti, testimonianze'', Feltrinelli, 1978 (In Italian) *Fantarella Filomena, ''Anna Kuliscioff'', Enciclopedia delle donne, 2018 (In Italian

*Mont'Arpizio Daniele, ''L'esperienza padovana del "socialismo medico"'', Università di Padova, 2021 (In Italian

*Polotti Giulio, Anna Kuliscioff, Fondazione Anna Kuliscioff, 1993 (In Italian

* Shepherd Naomi, ''"Anna Kuliscioff"'' ''Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia,'' Jewish Women's Archive, 2009

*Simili Raffaella, ''Rosenstejn, detta Kuliscioff Anna (Anja) — Scienza a due voci'', Scienza a due voci, 2009 (In Italian)

ANNA KULISCIOFF – RIBELLE PER AMORE

Marilena and Luca Dossena, L'Idea Magazine, 2014 (in Italian) {{DEFAULTSORT:Kuliscioff, Anna 1857 births 1925 deaths 19th-century women writers from the Russian Empire 20th-century Russian women writers Anarcha-feminists Burials at the Cimitero Monumentale di Milano Collectivist anarchists Emigrants from the Russian Empire to Italy Italian anarchists Italian anti-capitalists Italian feminists Italian journalists Italian people of Russian-Jewish descent Italian Socialist Party politicians Italian suffragists Italian women writers Italian writers Jewish anarchists Jewish feminists Jewish socialists Politicians from Simferopol People from Simferopolsky Uyezd Russian anarchists Russian anti-capitalists Russian Jews Russian revolutionaries Italian socialist feminists Unitary Socialist Party (Italy, 1922) politicians Jewish suffragists Russian socialist feminists Italian political party founders Female revolutionaries

feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

, an anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

influenced by Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary ...

, and eventually a Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

militant. She was mainly active in Italy, where she was one of the first women to graduate in medicine.

Biography

Anna Kuliscioff was born in 1857 nearSimferopol

Simferopol () is the second-largest city in the Crimea, Crimean Peninsula. The city, along with the rest of Crimea, is internationally recognised as part of Ukraine, and is considered the capital of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. However, ...

, in Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

. Her father, Moisei, was one of the five hundred privileged Jewish "merchants of the first guild" who were permitted to reside anywhere in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

.

Persecuted by the Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

n authorities, Kuliscioff took refuge in Paris, where she met the Italian anarchist Andrea Costa

Andrea is a given name which is common worldwide for both males and females, cognate to Andreas, Andrej and Andrew.

Origin of the name

The name derives from the Greek word ἀνήρ (''anēr''), genitive ἀνδρός (''andrós''), that ref ...

, her future partner. After being expelled from France in 1878, she settled in Italy and became the editor of ''Critica Sociale

''Critica Sociale'' is a left-wing List of newspapers in Italy, Italian newspaper. It is linked to the Italian Socialist Party. Before Benito Mussolini banned opposition newspapers in 1926, ''Critica Sociale'' was a prominent supporter of the ori ...

'', a major socialist paper, in 1891. An activist for causes such as women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

, Anna Kuliscioff was tried and imprisoned on several occasions.

Her real name was Anna Moiseevna Rozenstejn and she was the daughter of a wealthy Jewish family of merchants who guaranteed her a happy and dedicated childhood, so much so that she attended courses in philosophy at the University of Zurich

The University of Zürich (UZH, german: Universität Zürich) is a public research university located in the city of Zürich, Switzerland. It is the largest university in Switzerland, with its 28,000 enrolled students. It was founded in 1833 f ...

in Switzerland. She was endowed with an extraordinary memory and an exceptional predisposition to logical and rigorous reasoning. Encouraged from childhood to pursue studies with private teachers and rulers, she became interested in politics very early on.

In 1871, after studying foreign languages with private tutors, Kuliscioff was sent to study engineering at the Zürich Polytechnic

(colloquially)

, former_name = eidgenössische polytechnische Schule

, image = ETHZ.JPG

, image_size =

, established =

, type = Public

, budget = CHF 1.896 billion (2021)

, rector = Günther Dissertori

, president = Joël Mesot

, a ...

, where she additionally took courses in philosophy. Political outcasts, in whom the city flourished, acquainted her with rebel and egalitarian thoughts. Deserting her investigations, in 1873 she married Pyotr Makarevich, an individual progressive of honorable birth, and together they went back to ''Russia''. There they worked for progressive groups, first in Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

and afterward in Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

.

In 1874, Makarevich was condemned to five years of hard labor for his revolutionary activity. He died in jail. To avoid arrest. Anna escaped Odessa to live clandestinely, first in Kiev and then in Kharkov

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

, frequently singing in public parks to make money. In Kiev she aligned herself with revolutionaries associated with the Land and Freedom party, who engaged in terrorist acts against the tsarist authorities. When her colleagues in this armed group were arrested, she managed to escape.

In April 1877, using a false passport, she left Russia and moved to Paris, where she became a member of a small anarchist group which, following

In April 1877, using a false passport, she left Russia and moved to Paris, where she became a member of a small anarchist group which, following Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary ...

, preached the abolition of the state. One of the members was an Italian, Andrea Costa

Andrea is a given name which is common worldwide for both males and females, cognate to Andreas, Andrej and Andrew.

Origin of the name

The name derives from the Greek word ἀνήρ (''anēr''), genitive ἀνδρός (''andrós''), that ref ...

, with whom she had a relationship that endured for a very long time. During that period they were continually isolated by detainment and outcast. It was in Paris that Anna was first reported, in police records, as bearing the name Kuliscioff, a created name that distinguished her as coming from the East.

After being expelled from France in 1878, she settled in Italy and became the editor of ''Critica Sociale'', a major socialist paper, in 1891. An activist for causes such as women's suffrage, Anna Kuliscioff was tried and imprisoned on several occasions. Her views on Marxism influenced Filippo Turati

Filippo Turati (; 26 November 1857 – 29 March 1932) was an Italian sociologist, criminologist, poet and socialist politician.

Early life

Born in Canzo, province of Como, he graduated in law at the University of Bologna in 1877, and participa ...

, who became her partner. Together, they contributed to the creation of the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a socialist and later social-democratic political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parties of the country.

Founded in Genoa in 1892, ...

(PSI) as leaders of a reformist

Reformism is a political doctrine advocating the reform of an existing system or institution instead of its abolition and replacement.

Within the socialist movement, reformism is the view that gradual changes through existing institutions can eve ...

wing that came to oppose both Communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

(causing the split of the new Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party ( it, Partito Comunista Italiano, PCI) was a communist political party in Italy.

The PCI was founded as ''Communist Party of Italy'' on 21 January 1921 in Livorno by seceding from the Italian Socialist Party (PSI). ...

in 1921) and the irredentist

Irredentism is usually understood as a desire that one state annexes a territory of a neighboring state. This desire is motivated by ethnic reasons (because the population of the territory is ethnically similar to the population of the parent sta ...

attitudes of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

(who subsequently left the PSI). Their group was itself expelled from the PSI later in 1921, leading to the creation of a Unitary Socialist Party (PSU) – led by Turati, Kuliscioff, and Giacomo Matteotti

Giacomo Matteotti (; 22 May 1885 – 10 June 1924) was an Italian socialist politician. On 30 May 1924, he openly spoke in the Italian Parliament alleging the Fascists committed fraud in the recently held elections, and denounced the violence ...

, in opposition to the emergence of Fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

.

Romantically involved firstly with Andrea Costa and then with Filippo Turati, whom she both "converted" to Marxism. For this reason she was later defined as "the strong woman of Italian socialism". In 1947, a journalist of the Italian newspaper ''Corriere della Sera

The ''Corriere della Sera'' (; en, "Evening Courier") is an Italian daily newspaper published in Milan with an average daily circulation of 410,242 copies in December 2015.

First published on 5 March 1876, ''Corriere della Sera'' is one of It ...

'', Carlo Silvestri, declared: “the best political brain of Italian socialism was actually one of the most pleasant and proud women, in front of whom there was no one who, respectful and admiring, did not bend over, including Mussolini”.Socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the eco ...

, and the rise of the Fascist Party

The National Fascist Party ( it, Partito Nazionale Fascista, PNF) was a political party in Italy, created by Benito Mussolini as the political expression of Italian Fascism and as a reorganization of the previous Italian Fasces of Combat. The ...

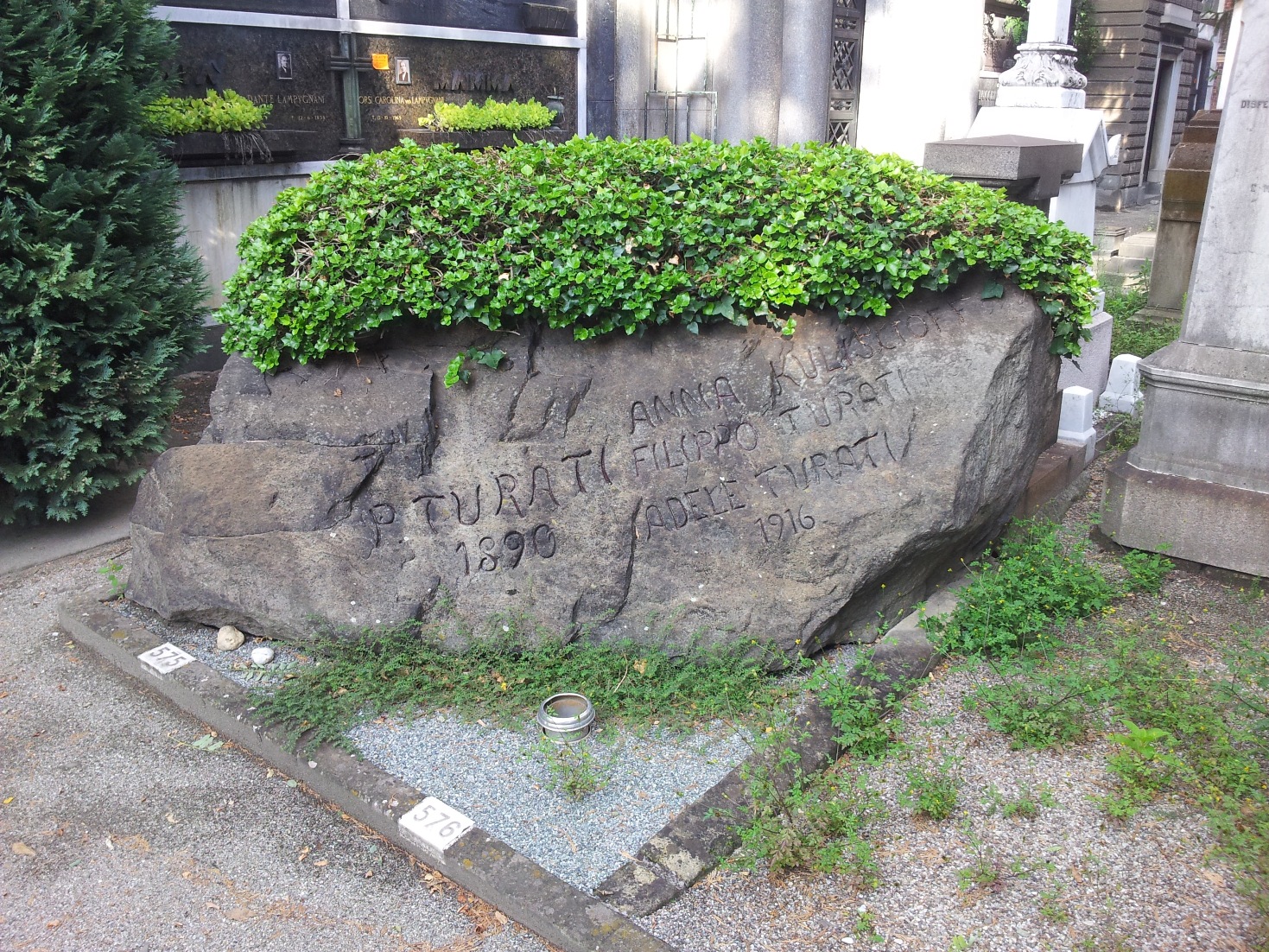

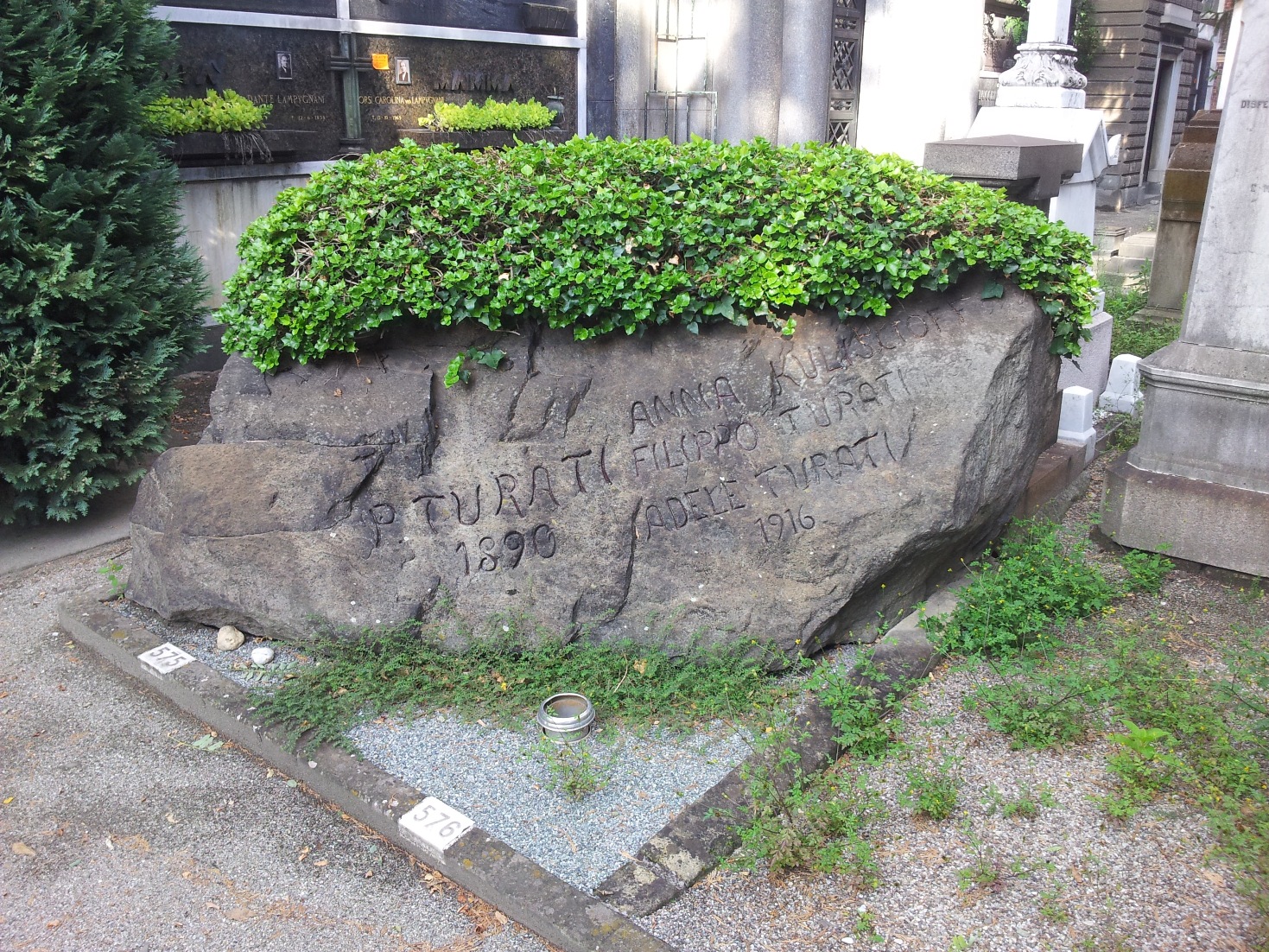

. Anna Kuliscioff died on 27 December 1925. Violence accompanied her funeral procession through the streets of central Milan on 29 December, when some fascists, hurling themselves against the carriages and tearing the drapes and crowns, transformed the funeral into a declaration of war.

Medical career

Because of her early lack of political commitment, Kuliscioff initially devoted herself to university studies. In 1882 she was forced to move to Switzerland where she enrolled in the faculty of medicine. Medicine satisfied her need to withdraw into an individual dimension and satisfied her aspiration for a social mission. Because of the long time spent in prison, she had contracted tuberculosis and milder climates were recommended. Thus she moved, with her daughter Andreina Costa, to

Because of her early lack of political commitment, Kuliscioff initially devoted herself to university studies. In 1882 she was forced to move to Switzerland where she enrolled in the faculty of medicine. Medicine satisfied her need to withdraw into an individual dimension and satisfied her aspiration for a social mission. Because of the long time spent in prison, she had contracted tuberculosis and milder climates were recommended. Thus she moved, with her daughter Andreina Costa, to Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

in 1884.

Due to bureaucratic inertia, it was decided to continue the experimental work elsewhere. She first went to the city of Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

where she met Cesare Lombroso

Cesare Lombroso (, also ; ; born Ezechia Marco Lombroso; 6 November 1835 – 19 October 1909) was an Italian criminologist, phrenologist, physician, and founder of the Italian School of Positivist Criminology. Lombroso rejected the establis ...

(1835–1909) and his daughters Paola (1872–1954) and Gina (1872–1944) and then to the city of Pavia

Pavia (, , , ; la, Ticinum; Medieval Latin: ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy in northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino river near its confluence with the Po. It has a population of c. 73,086. The city was the capit ...

, in 1885, where she attended one of the most prestigious laboratories, the one of the future Nobel laureate Camillo Golgi

Camillo Golgi (; 7 July 184321 January 1926) was an Italian biologist and pathologist known for his works on the central nervous system. He studied medicine at the University of Pavia (where he later spent most of his professional career) betwee ...

. She decided to prepare her graduation thesis focusing into a particularly demanding field such as epidemiology, devoting herself to the study of the pathogenesis of puerperal fevers which represented one of the main female causes of death: a particularly stimulating field of research and in clear development both as a result of the discoveries of microbiology

Microbiology () is the scientific study of microorganisms, those being unicellular (single cell), multicellular (cell colony), or acellular (lacking cells). Microbiology encompasses numerous sub-disciplines including virology, bacteriology, prot ...

and the appearance, also in Italy, of significant developments of a political nature in hygienic rehabilitation. This involved the affirmation of a concept of "social medicine

The field of social medicine seeks to implement social care through

# understanding how social and economic conditions impact health, disease and the practice of medicine and

# fostering conditions in which this understanding can lead to a health ...

", strongly characterized by a democratic and socialistic ideology. She concluded her thesis with the audacious hypothesis that ''the agent of the infection is to be identified not so much in a streptococcus'', as supposed by Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization, the latter of which was named afte ...

(1822–1895), ''but in microorganisms'' of another nature, the proteins of putrefaction

Putrefaction is the fifth stage of death, following pallor mortis, algor mortis, rigor mortis, and livor mortis. This process references the breaking down of a body of an animal, such as a human, post-mortem. In broad terms, it can be viewed ...

. Golgi first supported Kuliscioff's hypothesis; however, already in the following year she was denied by other collaborators of her laboratory in Pavia. Her graduation thesis is her only scientific publication, published in the " Gazzetta degli Ospedali".

After completing her graduation thesis, she returned to the

After completing her graduation thesis, she returned to the University of Naples

The University of Naples Federico II ( it, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II) is a public university in Naples, Italy. Founded in 1224, it is the oldest public non-sectarian university in the world, and is now organized into 26 depar ...

and in 1886 became the first woman to graduate in medicine and surgery. After graduating in Medicine, she moved again in 1887, this time to specialize in the medical clinic of Achille De Giovanni (1838–1916) in Padua. In 1888 she specialized in gynecology

Gynaecology or gynecology (see spelling differences) is the area of medicine that involves the treatment of women's diseases, especially those of the reproductive organs. It is often paired with the field of obstetrics, forming the combined are ...

, first in Turin, then in Padua. The choice to concentrate her own studies in the field of gynecology appears as a demonstration of Kuliscioff's fidelity to the feminist cause. Thus Kuliscioff could find a link between professional and political activity. During these years she had been in a relationship with Filippo Turati. She decided to move to Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

with him. She tried to get hired as a doctor at the Maggiore Hospital, but she was rejected because she was a woman.

After both her academic career and that of a hospital doctor, she began her career as a "''doctor of the poor''" in via San Pietro all'Olmo 18. She offered free medical assistance to poor women. The profession of doctor of the poor forced her to be a spectator of the miserable living conditions of the Milan workers. She wanted to intervene politically in this field. Becoming a "doctor of the poor" appeared to her as a sort of force of will. She was truly admired for her work; her daily visits were expected as a blessing, in fact it was not a visit from a doctor, it was something more. Anna Kuliscioff was considered a comforter, a friend, trustworthy woman of those who suffered and their beloved. Her patients described her as a woman who was able to penetrate the depths of souls. She treated the poor people with affectionate familiarity. Kuliscioff did not dedicate her care only to the poor, in fact, even the ladies of the

After both her academic career and that of a hospital doctor, she began her career as a "''doctor of the poor''" in via San Pietro all'Olmo 18. She offered free medical assistance to poor women. The profession of doctor of the poor forced her to be a spectator of the miserable living conditions of the Milan workers. She wanted to intervene politically in this field. Becoming a "doctor of the poor" appeared to her as a sort of force of will. She was truly admired for her work; her daily visits were expected as a blessing, in fact it was not a visit from a doctor, it was something more. Anna Kuliscioff was considered a comforter, a friend, trustworthy woman of those who suffered and their beloved. Her patients described her as a woman who was able to penetrate the depths of souls. She treated the poor people with affectionate familiarity. Kuliscioff did not dedicate her care only to the poor, in fact, even the ladies of the bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They ...

entrusted themselves to her care. Unfortunately this didn't last for too long due to her physical conditions. She retired to her home where she continued her lively political militancy. During the 20th century, the presence of women, first in medical schools and later in hospitals and every healthcare facility, registered a slow but constant increase.

Selected works

* ''Il monopolio dell'uomo: conferenza tenuta nel circolo filologico milanese'', Milan, Critica sociale, 1894 (''The Monopoly of Man'', trans.Lorenzo Chiesa

Lorenzo Chiesa (born 25 April 1976) is a philosopher, critical theorist, translator, and professor whose academic research and works focus on the intersection between ontology, psychoanalysis, and political theory.

Biography

Chiesa is currently a ...

(MIT Press, 2021))

* ''Il voto alle donne: polemica in famiglia per la propaganda del suffragio universale in Italia'', Milan, Uffici della critica sociale, 1910 (with Filippo Turati, in Italian)

* ''Proletariato femminile e Partito socialista: relazione al Congresso nazionale socialista 1910'', Milan, Critica sociale, 1910

* ''Donne proletarie, a voi...: per il suffragio femminile'', Milan, Società editrice Avanti!, 1913

* ''Lettere d'amore a Andrea Costa, 1880–1909'', Milan, Feltrinelli, 1976

*''Amore e socialismo. Un carteggio inedito'', La nuova Italia, 2001 (with Filippo Turati, in Italian)

References

Bibliography

* Bolpagni Paolo, ''Arte, socialità, politica. Articoli dell’"Avanti della Domenica" 1903–1907'', Fondazione Anna Kuliscioff – EDIFIS, 2011 * Bolpagni Paolo, ''L’arte nell’"Avanti della Domenica" 1903–1907'', Mazzotta, 2008 * Borghi Luca, ''Umori – il fattore umano nella storia delle discipline biomediche'', SEU, 2012 (In Italian) * Casalini Maria,Anna Kuliscioff. La signora del socialismo italiano

'. Editori Riuniti Univ. Press, 2013 (In Italian) * Damiani Franco and Rodriguez Fabio (edited by), ''Anna Kuliscioff: immagini, scritti, testimonianze'', Feltrinelli, 1978 (In Italian) *Fantarella Filomena, ''Anna Kuliscioff'', Enciclopedia delle donne, 2018 (In Italian

*Mont'Arpizio Daniele, ''L'esperienza padovana del "socialismo medico"'', Università di Padova, 2021 (In Italian

*Polotti Giulio, Anna Kuliscioff, Fondazione Anna Kuliscioff, 1993 (In Italian

* Shepherd Naomi, ''"Anna Kuliscioff"'' ''Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia,'' Jewish Women's Archive, 2009

*Simili Raffaella, ''Rosenstejn, detta Kuliscioff Anna (Anja) — Scienza a due voci'', Scienza a due voci, 2009 (In Italian)

External links

ANNA KULISCIOFF – RIBELLE PER AMORE

Marilena and Luca Dossena, L'Idea Magazine, 2014 (in Italian) {{DEFAULTSORT:Kuliscioff, Anna 1857 births 1925 deaths 19th-century women writers from the Russian Empire 20th-century Russian women writers Anarcha-feminists Burials at the Cimitero Monumentale di Milano Collectivist anarchists Emigrants from the Russian Empire to Italy Italian anarchists Italian anti-capitalists Italian feminists Italian journalists Italian people of Russian-Jewish descent Italian Socialist Party politicians Italian suffragists Italian women writers Italian writers Jewish anarchists Jewish feminists Jewish socialists Politicians from Simferopol People from Simferopolsky Uyezd Russian anarchists Russian anti-capitalists Russian Jews Russian revolutionaries Italian socialist feminists Unitary Socialist Party (Italy, 1922) politicians Jewish suffragists Russian socialist feminists Italian political party founders Female revolutionaries