The Anglo-Saxons were a

cultural group

Cultural identity is a part of a person's identity, or their self-conception and self-perception, and is related to nationality, ethnicity, religion, social class, generation, locality or any kind of social group that has its own distinct cultu ...

who inhabited England in the

Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from

mainland Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

in the 5th century. However, the

ethnogenesis

Ethnogenesis (; ) is "the formation and development of an ethnic group".

This can originate by group self-identification or by outside identification.

The term ''ethnogenesis'' was originally a mid-19th century neologism that was later introdu ...

of the Anglo-Saxons happened within Britain, and the identity was not merely imported. Anglo-Saxon identity arose from interaction between incoming groups from several

Germanic tribes

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and ear ...

, both amongst themselves, and with

indigenous Britons. Many of the natives, over time, adopted Anglo-Saxon culture and language and were assimilated. The Anglo-Saxons established the concept, and the

Kingdom

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

, of England, and though the modern

English language

English is a West Germanic language of the Indo-European language family, with its earliest forms spoken by the inhabitants of early medieval England. It is named after the Angles, one of the ancient Germanic peoples that migrated to the is ...

owes somewhat less than 26% of its words to their language, this includes the vast majority of words used in everyday speech.

Historically, the Anglo-Saxon period denotes the period in Britain between about 450 and 1066, after

their initial settlement and up until the

Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conque ...

.

[ Higham, Nicholas J., and Martin J. Ryan. ''The Anglo-Saxon World''. Yale University Press, 2013.]

The early Anglo-Saxon period includes the creation of an

English nation

The English people are an ethnic group and nation native to England, who speak the English language, a West Germanic language, and share a common history and culture. The English identity is of Anglo-Saxon origin, when they were known in O ...

, with many of the aspects that survive today, including regional government of

shire

Shire is a traditional term for an administrative division of land in Great Britain and some other English-speaking countries such as Australia and New Zealand. It is generally synonymous with county. It was first used in Wessex from the beginn ...

s and

hundreds. During this period,

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

was established and there was a flowering of literature and language. Charters and law were also established. The term ''Anglo-Saxon'' is popularly used for the language that was spoken and written by the Anglo-Saxons in England and southeastern Scotland from at least the mid-5th century until the mid-12th century. In scholarly use, it is more commonly called

Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

.

The history of the Anglo-Saxons is the history of a cultural identity. It developed from divergent groups in association with the people's adoption of Christianity and was integral to the founding of various kingdoms. Threatened by extended Danish

Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

invasions and military occupation of eastern England, this identity was re-established; it dominated until after the Norman Conquest. Anglo-Saxon material culture can still be seen in

architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing building ...

,

dress styles,

illuminated texts, metalwork and other art. Behind the symbolic nature of these cultural emblems, there are strong elements of tribal and lordship ties. The elite declared themselves kings who developed ''

burh

A burh () or burg was an Old English fortification or fortified settlement. In the 9th century, raids and invasions by Vikings prompted Alfred the Great to develop a network of burhs and roads to use against such attackers. Some were new constru ...

s'', and identified their roles and peoples in Biblical terms. Above all, as archaeologist

Helena Hamerow

Helena Francisca Hamerow, FSA (born 18 September 1961) is an American-born archaeologist, best known for her work on the archeology of early medieval communities in Northwestern Europe. She is Professor of Early Medieval archaeology and former ...

has observed, "local and extended kin groups remained...the essential unit of production throughout the Anglo-Saxon period." The effects persist, as a 2015 study found the genetic makeup of British populations today shows divisions of the tribal political units of the early Anglo-Saxon period.

The term ''Anglo-Saxon'' began to be used in the 8th century (in Latin and on the continent) to distinguish "Germanic" groups in Britain from those on the continent (

Old Saxony

"Old Saxony" is the original homeland of the Saxons. It corresponds roughly to the modern German states of Lower Saxony, eastern part of modern North Rhine-Westphalia state (Westphalia), Nordalbingia (Holstein, southern part of Schleswig-Holstein ...

and

Anglia in

Northern Germany

Northern Germany (german: link=no, Norddeutschland) is a linguistic, geographic, socio-cultural and historic region in the northern part of Germany which includes the coastal states of Schleswig-Holstein, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Lower Saxony an ...

).

Catherine Hills

Catherine Mary Hills is a British archaeologist and academic, who is a leading expert in Anglo-Saxon material culture. She is a senior research fellow at the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge.

Education

...

summarised the views of many modern scholars in her observation that attitudes towards Anglo-Saxons, and hence the interpretation of their culture and history, have been "more contingent on contemporary political and religious theology as on any kind of evidence."

Ethnonym

The

Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

ethnonym

An ethnonym () is a name applied to a given ethnic group. Ethnonyms can be divided into two categories: exonyms (whose name of the ethnic group has been created by another group of people) and autonyms, or endonyms (whose name is created and used ...

''Angul-Seaxan'' comes from the Latin ''Angli-Saxones'' and became the name of the peoples the English monk

Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom o ...

called ''Angli'' around 730 and the British monk

Gildas

Gildas (Breton: ''Gweltaz''; c. 450/500 – c. 570) — also known as Gildas the Wise or ''Gildas Sapiens'' — was a 6th-century British monk best known for his scathing religious polemic ''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae'', which recounts ...

called ''Saxones'' around 530. Anglo-Saxon is a term that was rarely used by Anglo-Saxons themselves. It is likely they identified as ''ængli'', ''Seaxe'' or, more probably, a local or tribal name such as ''Mierce'', ''Cantie'', ''Gewisse'', ''Westseaxe'', or ''Norþanhymbre''. After the

Viking Age

The Viking Age () was the period during the Middle Ages when Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonizing, conquest, and trading throughout Europe and reached North America. It followed the Migration Period and the Ger ...

, an Anglo-Scandinavian identity developed in the

Danelaw

The Danelaw (, also known as the Danelagh; ang, Dena lagu; da, Danelagen) was the part of England in which the laws of the Danes held sway and dominated those of the Anglo-Saxons. The Danelaw contrasts with the West Saxon law and the Mercian ...

.

The term ''Angli Saxones'' seems to have first been used in mainland writing of the 8th century;

Paul the Deacon

Paul the Deacon ( 720s 13 April in 796, 797, 798, or 799 AD), also known as ''Paulus Diaconus'', ''Warnefridus'', ''Barnefridus'', or ''Winfridus'', and sometimes suffixed ''Cassinensis'' (''i.e.'' "of Monte Cassino"), was a Benedictine monk, s ...

uses it to distinguish the English Saxons from the mainland Saxons (''Ealdseaxe'', literally, 'old Saxons'). The name, therefore, seemed to mean "English" Saxons.

The Christian church seems to have used the word Angli; for example in the story of

Pope Gregory I

Pope Gregory I ( la, Gregorius I; – 12 March 604), commonly known as Saint Gregory the Great, was the bishop of Rome from 3 September 590 to his death. He is known for instigating the first recorded large-scale mission from Rome, the Gregori ...

and his remark, "''Non Angli sed angeli''" (not English but angels). The terms ''ænglisc'' (the language) and ''Angelcynn'' (the people) were also used by West Saxon

King Alfred

Alfred the Great (alt. Ælfred 848/849 – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who bot ...

to refer to the people; in doing so he was following established practice. Bede and

Alcuin

Alcuin of York (; la, Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus; 735 – 19 May 804) – also called Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin – was a scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student o ...

used ''gens Anglorum'' to refer to all the Anglo-Saxons: Bede referred to the people of the pre-Christian period as 'Saxons', but all becoming 'Angles' after accepting Christianity (in accordance with Pope Gregory I's use of the word ''Anglorum'' for the entire mission); Alcuin contrasted 'Saxons' with 'Angles', the former referring only to continental Saxons and the latter being associated with Britain. Bede's choice of terminology contrasted with the norm among his contemporaries, both Angle and Saxon, who collectively identified as 'Saxons' and their country as ''Saxonia''.

Aethelweard also followed Bede's usage, systematically editing all mentions of the word 'Saxon' to 'English'.

The first use of the term Anglo-Saxon amongst the insular sources is in the titles for

Æthelstan

Æthelstan or Athelstan (; ang, Æðelstān ; on, Aðalsteinn; ; – 27 October 939) was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 924 to 927 and King of the English from 927 to his death in 939. He was the son of King Edward the Elder and his first ...

around 924: ''Angelsaxonum Denorumque gloriosissimus rex'' (most glorious king of the Anglo-Saxons and of the Danes) and ''rex Angulsexna and Norþhymbra imperator paganorum gubernator Brittanorumque propugnator'' (king of the Anglo-Saxons and emperor of the Northumbrians, governor of the pagans, and defender of the Britons). At other times he uses the term ''rex Anglorum'' (king of the English), which presumably meant both Anglo-Saxons and Danes. Alfred used ''Anglosaxonum Rex''. The term (King of the English) is used by

Æthelred

Æthelred (; ang, Æþelræd ) or Ethelred () is an Old English personal name (a compound of '' æþele'' and '' ræd'', meaning "noble counsel" or "well-advised") and may refer to:

Anglo-Saxon England

* Æthelred and Æthelberht, legendary prin ...

.

Cnut the Great

Cnut (; ang, Cnut cyning; non, Knútr inn ríki ; or , no, Knut den mektige, sv, Knut den Store. died 12 November 1035), also known as Cnut the Great and Canute, was King of England from 1016, King of Denmark from 1018, and King of Norwa ...

, King of Denmark, England, and Norway, in 1021 was the first to refer to the land and not the people with this term: (King of all England). These titles express the sense that the Anglo-Saxons were a Christian people with a king anointed by God.

The indigenous

Common Brittonic

Common Brittonic ( cy, Brythoneg; kw, Brythonek; br, Predeneg), also known as British, Common Brythonic, or Proto-Brittonic, was a Celtic language spoken in Britain and Brittany.

It is a form of Insular Celtic, descended from Proto-Celtic, a ...

speakers referred to Anglo-Saxons as ''Saxones'' or possibly ''Saeson'' (the word ''Saeson'' is the modern Welsh word for 'English people'); the equivalent word in

Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well as ...

is ''

Sasannach'' and in the

Irish language

Irish ( Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was ...

, ''Sasanach''. Catherine Hills suggests that it is no accident "that the English call themselves by the name sanctified by the Church, as that of a people chosen by God, whereas their enemies use the name originally applied to piratical raiders".

Early Anglo-Saxon history (410–660)

The early Anglo-Saxon period covers the history of medieval Britain that starts from the end of

Roman rule. It is a period widely known in European history as the

Migration Period

The Migration Period was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Roman ...

, also the ''Völkerwanderung'' ("migration of peoples" in

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

). This was a period of intensified

human migration

Human migration is the movement of people from one place to another with intentions of settling, permanently or temporarily, at a new location (geographic region). The movement often occurs over long distances and from one country to another (ex ...

in Europe from about 375 to 800. The migrants were

Germanic tribes

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and ear ...

such as the

Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe ...

,

Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

,

Angles

The Angles ( ang, Ængle, ; la, Angli) were one of the main Germanic peoples who settled in Great Britain in the post-Roman period. They founded several kingdoms of the Heptarchy in Anglo-Saxon England. Their name is the root of the name ' ...

,

Saxons

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

,

Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 and ...

,

Suebi

The Suebi (or Suebians, also spelled Suevi, Suavi) were a large group of Germanic peoples originally from the Elbe river region in what is now Germany and the Czech Republic. In the early Roman era they included many peoples with their own names ...

,

Frisii

The Frisii were an ancient Germanic tribe living in the low-lying region between the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and the River Ems, and the presumed or possible ancestors of the modern-day ethnic Dutch.

The Frisii lived in the coastal area ...

, and

Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

; they were later pushed westwards by the

Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

,

Avars,

Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

,

Bulgars

The Bulgars (also Bulghars, Bulgari, Bolgars, Bolghars, Bolgari, Proto-Bulgarians) were Turkic semi-nomadic warrior tribes that flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region during the 7th century. They became known as nomad ...

, and

Alans

The Alans (Latin: ''Alani'') were an ancient and medieval Iranian nomadic pastoral people of the North Caucasus – generally regarded as part of the Sarmatians, and possibly related to the Massagetae. Modern historians have connected the Al ...

. The migrants to Britain might also have included the Huns and

Rugini The Rugini were a tribe in Pomerania. They were only mentioned once, in a list of yet to be converted tribes drawn up by the English monk Bede (also Beda venerabilis) in his ''Historia ecclesiastica'' of the early 8th century:Johannes Hoops, Herbert ...

.

Until AD 400,

Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the period in classical antiquity when large parts of the island of Great Britain were under occupation by the Roman Empire. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410. During that time, the territory conquered was ...

, the province of ''Britannia'', was an integral, flourishing part of the

Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period fr ...

, occasionally disturbed by internal rebellions or barbarian attacks, which were subdued or repelled by the large contingent of

imperial troops stationed in the province. By 410, however,

the imperial forces had been withdrawn to deal with crises in other parts of the empire, and the

Romano-Britons were left to fend for themselves in what is called the post-Roman or "

sub-Roman" period of the 5th century.

Migration (410–560)

It is now widely accepted that the Anglo-Saxons were not just transplanted Germanic invaders and settlers from the Continent, but the outcome of insular interactions and changes.

Writing c. 540,

Gildas

Gildas (Breton: ''Gweltaz''; c. 450/500 – c. 570) — also known as Gildas the Wise or ''Gildas Sapiens'' — was a 6th-century British monk best known for his scathing religious polemic ''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae'', which recounts ...

mentions that sometime in the 5th century, a council of leaders in Britain agreed that some land in the east of southern Britain would be given to the Saxons on the basis of a treaty, a ''foedus,'' by which the Saxons would defend the Britons against attacks from the

Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples who lived in what is now northern and eastern Scotland (north of the Firth of Forth) during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and what their culture was like can be inferred from ea ...

and

Scoti

''Scoti'' or ''Scotti'' is a Latin name for the Gaels,Duffy, Seán. ''Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2005. p.698 first attested in the late 3rd century. At first it referred to all Gaels, whether in Ireland or Great Britain, but l ...

in exchange for food supplies. The most contemporaneous textual evidence is the ''

Chronica Gallica of 452

The ''Chronica Gallica of 452'', also called the ''Gallic Chronicle of 452'', is a Latin chronicle of Late Antiquity, presented in the form of annals, which continues that of Jerome. It was edited by Theodor Mommsen in the ''Monumenta Germaniae His ...

'', which records for the year 441: "The British provinces, which to this time had suffered various defeats and misfortunes, are reduced to Saxon rule." This is an earlier date than that of 451 for the "coming of the Saxons" used by

Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom o ...

in his ''

Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum

The ''Ecclesiastical History of the English People'' ( la, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum), written by Bede in about AD 731, is a history of the Christian Churches in England, and of England generally; its main focus is on the conflict be ...

,'' written around 731. It has been argued that Bede misinterpreted his (scanty) sources and that the chronological references in the ''

Historia Britonnum'' yield a plausible date of around 428.

Gildas recounts how a war broke out between the Saxons and the local population – historian Nick Higham calls it the "War of the Saxon Federates" – which ended shortly after the

siege at 'Mons Badonicus'. The Saxons went back to "their eastern home". Gildas calls the peace a "grievous divorce with the barbarians". The price of peace, Higham argues, was a better treaty for the Saxons, giving them the ability to receive tribute from people across the lowlands of Britain.

The archaeological evidence agrees with this earlier timescale. In particular, the work of Catherine Hills and Sam Lucy on the evidence of

Spong Hill

Spong Hill is an Anglo-Saxon cemetery site located south of North Elmham in Norfolk, England. It is the largest known Early Anglo-Saxon cremation site. The site consists of a large cremation cemetery and a smaller, 6th century burial cemetery of ...

has moved the chronology for the settlement earlier than 450, with a significant number of items now in phases before Bede's date.

This vision of the Anglo-Saxons exercising extensive political and military power at an early date remains contested. The most developed vision of a continuation in sub-Roman Britain, with control over its own political and military destiny for well over a century, is that of Kenneth Dark, who suggests that the sub-Roman elite survived in culture, politics and military power up to .

[Higham, Nick. "From sub-Roman Britain to Anglo-Saxon England: Debating the Insular Dark Ages." ''History Compass'' 2.1 (2004).] Bede, however, identifies three phases of settlement: an exploration phase, when mercenaries came to protect the resident population; a migration phase, which was substantial as implied by the statement that ''Anglus'' was deserted; and an establishment phase, in which Anglo-Saxons started to control areas, implied in Bede's statement about the origins of the tribes.

Scholars have not reached a consensus on the number of migrants who entered Britain in this period. Härke argues that the figure is around 100,000 to 200,000.

[Härke, Heinrich. "Anglo-Saxon Immigration and Ethnogenesis." ''Medieval Archaeology'' 55.1 (2011): 1–28.] Bryan Ward-Perkins also argues for up to 200,000 incomers. Catherine Hills suggests the number is nearer to 20,000. A computer simulation showed that a migration of 250,000 people from mainland Europe could have been accomplished in as little as 38 years.

Recent genetic and isotope studies have suggested that the migration, which included both men and women, continued over several centuries, possibly allowing for significantly more new arrivals than has been previously thought. By around 500, communities of Anglo-Saxons were established in southern and eastern Britain.

Härke and Michael Wood estimate that the British population in the area that eventually became Anglo-Saxon England was around one million by the start of the fifth century;

however, what happened to the Britons has been debated. The traditional explanation for their archaeological and linguistic invisibility

[Coates, Richard. "Invisible Britons: The view from linguistics. Paper circulated in connection with the conference Britons and Saxons, 14–16 April. University of Sussex Linguistics and English Language Department." (2004)] is that the Anglo-Saxons either killed them or drove them to the mountainous fringes of Britain, a view broadly supported by the few available sources from the period. However, there is evidence of continuity in the systems of landscape and local governance, decreasing the likelihood of such a cataclysmic event, at least in parts of England. Thus, scholars have suggested other, less violent explanations by which the culture of the Anglo-Saxons, whose core area of large-scale settlement was likely restricted to what is now

southeastern England,

East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

and

Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire ...

,

could have come to be ubiquitous across lowland Britain. Härke has posited a scenario in which the Anglo-Saxons, in expanding westward, outbred the Britons, eventually reaching a point where their descendants made up a larger share of the population of what was to become England.

It has also been proposed that the Britons were disproportionately affected by plagues arriving through Roman trade links, which, combined with a large emigration to

Armorica

Armorica or Aremorica (Gaulish: ; br, Arvorig, ) is the name given in ancient times to the part of Gaul between the Seine and the Loire that includes the Brittany Peninsula, extending inland to an indeterminate point and down the Atlantic Coast ...

,

could have substantially decreased their numbers.

Even so, there is general agreement that the kingdoms of

Wessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

,

Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879)Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era=Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, ye ...

and

Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

housed significant numbers of Britons. Härke states that "it is widely accepted that in the north of England, the native population survived to a greater extent than the south," and that in Bernicia, "a small group of immigrants may have replaced the native British elite and took over the kingdom as a going concern."

Evidence for the natives in Wessex, meanwhile, can be seen in the late seventh century

laws of King Ine, which gave them fewer rights and a lower status than the Saxons. This might have provided an incentive for Britons in the kingdom to adopt Anglo-Saxon culture. Higham points out that "in circumstances where freedom at law, acceptance with the kindred, access to patronage, and the use and possession of weapons were all exclusive to those who could claim Germanic descent, then speaking Old English without Latin or Brittonic inflection had considerable value."

There is evidence for a British influence on the emerging Anglo-Saxon elite classes. The Wessex royal line was traditionally founded by a man named

Cerdic

Cerdic (; la, Cerdicus) is described in the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' as a leader of the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, being the founder and first king of Saxon Wessex, reigning from 519 to 534 AD. Subsequent kings of Wessex were each cla ...

, an undoubtedly Celtic name cognate to

Ceretic (the name of two British kings, ultimately derived from *Corotīcos). This may indicate that Cerdic was a native Briton and that his dynasty became anglicised over time.

[Myres, J.N.L. (1989) ''The English Settlements''. Oxford University Press, pp. 146–147] A number of Cerdic's alleged descendants also possessed Celtic names, including the '

Bretwalda

''Bretwalda'' (also ''brytenwalda'' and ''bretenanwealda'', sometimes capitalised) is an Old English word. The first record comes from the late 9th-century ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle''. It is given to some of the rulers of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms from ...

'

Ceawlin

Ceawlin (also spelled Ceaulin and Caelin, died ''ca.'' 593) was a King of Wessex. He may have been the son of Cynric of Wessex and the grandson of Cerdic of Wessex, whom the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' represents as the leader of the first grou ...

. The last man in this dynasty to have a Brittonic name was King

Caedwalla, who died as late as 689. In Mercia, too, several kings bear seemingly Celtic names, most notably

Penda

Penda (died 15 November 655)Manuscript A of the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' gives the year as 655. Bede also gives the year as 655 and specifies a date, 15 November. R. L. Poole (''Studies in Chronology and History'', 1934) put forward the theor ...

. As far east as

Lindsey Lindsey may refer to :

Places Canada

* Lindsey Lake, Nova Scotia

England

* Parts of Lindsey, one of the historic Parts of Lincolnshire and an administrative county from 1889 to 1974

** East Lindsey, an administrative district in Lincolnshire, ...

, the Celtic name ''Caedbaed'' appears in the list of kings.

Recent genetic studies, based on data collected from skeletons found in Iron Age, Roman and Anglo-Saxon era burials, have concluded that the ancestry of the modern English population contains large contributions from both Anglo-Saxon migrants and Romano-British natives.

Development of an Anglo-Saxon society (560–610)

In the last half of the 6th century, four structures contributed to the development of society; they were the position and freedoms of the ''ceorl,'' the smaller tribal areas coalescing into larger kingdoms, the elite developing from warriors to kings, and Irish monasticism developing under

Finnian (who had consulted Gildas) and his pupil

Columba

Columba or Colmcille; gd, Calum Cille; gv, Colum Keeilley; non, Kolban or at least partly reinterpreted as (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is toda ...

.

The Anglo-Saxon farms of this period are often falsely supposed to be "peasant farms". However, a

''ceorl'', who was the lowest ranking freeman in early Anglo-Saxon society, was not a peasant but an arms-owning male with the support of a kindred, access to law and the ''

wergild

Weregild (also spelled wergild, wergeld (in archaic/historical usage of English), weregeld, etc.), also known as man price (blood money), was a precept in some archaic legal codes whereby a monetary value was established for a person's life, to b ...

''; situated at the apex of an extended household working at least one

hide of land. The farmer had freedom and rights over lands, with provision of a rent or duty to an overlord who provided only slight lordly input. Most of this land was common outfield arable land (of an outfield-infield system) that provided individuals with the means to build a basis of kinship and group cultural ties.

The

Tribal Hidage

Image:Tribal Hidage 2.svg, 400px, alt=insert description of map here, The tribes of the Tribal Hidage. Where an appropriate article exists, it can be found by clicking on the name.

rect 275 75 375 100 w:Elmet

rect 375 100 450 150 w:Hatfield Ch ...

lists thirty-five peoples, or tribes, with assessments in hides, which may have originally been defined as the area of land sufficient to maintain one family. The assessments in the ''Hidage'' reflect the relative size of the provinces.

[Yorke, Barbara. ''Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England''. Routledge, 2002.] Although varying in size, all thirty-five peoples of the Tribal Hidage were of the same status, in that they were areas which were ruled by their own elite family (or royal houses), and so were assessed independently for payment of tribute. By the end of the sixth century, larger kingdoms had become established on the south or east coasts. They include the provinces of the

Jutes of Hampshire and Wight, the

South Saxons

la, Regnum Sussaxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the South Saxons

, capital =

, era = Heptarchy

, status = Vassal of Wessex (686–726, 827–860)Vassal of Mercia (771–796)

, governm ...

,

Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, the

East Saxons

la, Regnum Orientalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the East Saxons

, common_name = Essex

, era = Heptarchy

, status =

, status_text =

, government_type = Monarch ...

,

East Angles

la, Regnum Orientalium Anglorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the East Angles

, common_name = East Anglia

, era =

, status = Great Kingdom

, status_text = Independent (6th centu ...

,

Lindsey Lindsey may refer to :

Places Canada

* Lindsey Lake, Nova Scotia

England

* Parts of Lindsey, one of the historic Parts of Lincolnshire and an administrative county from 1889 to 1974

** East Lindsey, an administrative district in Lincolnshire, ...

and (north of the Humber)

Deira

Deira ( ; Old Welsh/Cumbric: ''Deywr'' or ''Deifr''; ang, Derenrice or ) was an area of Post-Roman Britain, and a later Anglian kingdom.

Etymology

The name of the kingdom is of Brythonic origin, and is derived from the Proto-Celtic *''daru' ...

and

Bernicia

Bernicia ( ang, Bernice, Bryneich, Beornice; la, Bernicia) was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom established by Anglian settlers of the 6th century in what is now southeastern Scotland and North East England.

The Anglian territory of Bernicia was ap ...

. Several of these kingdoms may have had as their initial focus a territory based on a former Roman ''

civitas

In Ancient Rome, the Latin term (; plural ), according to Cicero in the time of the late Roman Republic, was the social body of the , or citizens, united by law (). It is the law that binds them together, giving them responsibilities () on th ...

''.

By the end of the sixth century, the leaders of these communities were styling themselves kings, though it should not be assumed that all of them were Germanic in origin. The

Bretwalda

''Bretwalda'' (also ''brytenwalda'' and ''bretenanwealda'', sometimes capitalised) is an Old English word. The first record comes from the late 9th-century ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle''. It is given to some of the rulers of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms from ...

concept is taken as evidence of a number of early Anglo-Saxon elite families. What Bede seems to imply in his ''Bretwalda'' is the ability of leaders to extract tribute, overawe and/or protect the small regions, which may well have been relatively short-lived in any one instance. Ostensibly "Anglo-Saxon" dynasties variously replaced one another in this role in a discontinuous but influential and potent roll call of warrior elites. Importantly, whatever their origin or whenever they flourished, these dynasties established their claim to lordship through their links to extended kin, and possibly mythical, ties. As Helen Geake points out, "they all just happened to be related back to Woden".

The process from warrior to ''cyning'' – Old English for king – is described in ''

Beowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ang, Bēowulf ) is an Old English epic poem in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and most often translated works of Old English literature. The ...

'':

Conversion to Christianity (588–686)

In 565,

Columba

Columba or Colmcille; gd, Calum Cille; gv, Colum Keeilley; non, Kolban or at least partly reinterpreted as (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is toda ...

, a monk from Ireland who studied at the monastic school of

Moville under St.

Finnian, reached

Iona

Iona (; gd, Ì Chaluim Chille (IPA: �iːˈxaɫ̪ɯimˈçiʎə, sometimes simply ''Ì''; sco, Iona) is a small island in the Inner Hebrides, off the Ross of Mull on the western coast of Scotland. It is mainly known for Iona Abbey, though there ...

as a self-imposed exile. The influence of the monastery of Iona would grow into what

Peter Brown has described as an "unusually extensive spiritual empire," which "stretched from western Scotland deep to the southwest into the heart of Ireland and, to the southeast, it reached down throughout northern Britain, through the influence of its sister monastery Lindisfarne."

In June 597 Columba died. At this time,

Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berbers, Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia (Roman pr ...

landed on the

Isle of Thanet

The Isle of Thanet () is a peninsula forming the easternmost part of Kent, England. While in the past it was separated from the mainland by the Wantsum Channel, it is no longer an island.

Archaeological remains testify to its settlement in anc ...

and proceeded to King Æthelberht of Kent, Æthelberht's main town of Canterbury. He had been the prior of a monastery in Rome when Pope Pope Gregory I, Gregory the Great chose him in 595 to lead the Gregorian mission to Britain to Christianization, Christianise the Kingdom of Kent from their native Anglo-Saxon paganism. Kent was probably chosen because Æthelberht had married a Christian princess, Bertha of Kent, Bertha, daughter of Charibert I the List of Frankish kings, king of Paris, who was expected to exert some influence over her husband. Æthelberht was converted to Christianity, churches were established, and wider-scale conversion to Christianity began in the kingdom. Æthelberht's law for Kent, the earliest written code in any Germanic language, instituted a complex system of fines. Kent was rich, with strong trade ties to the continent, and Æthelberht may have instituted royal control over trade. For the first time following the Anglo-Saxon invasion, coins began circulating in Kent during his reign.

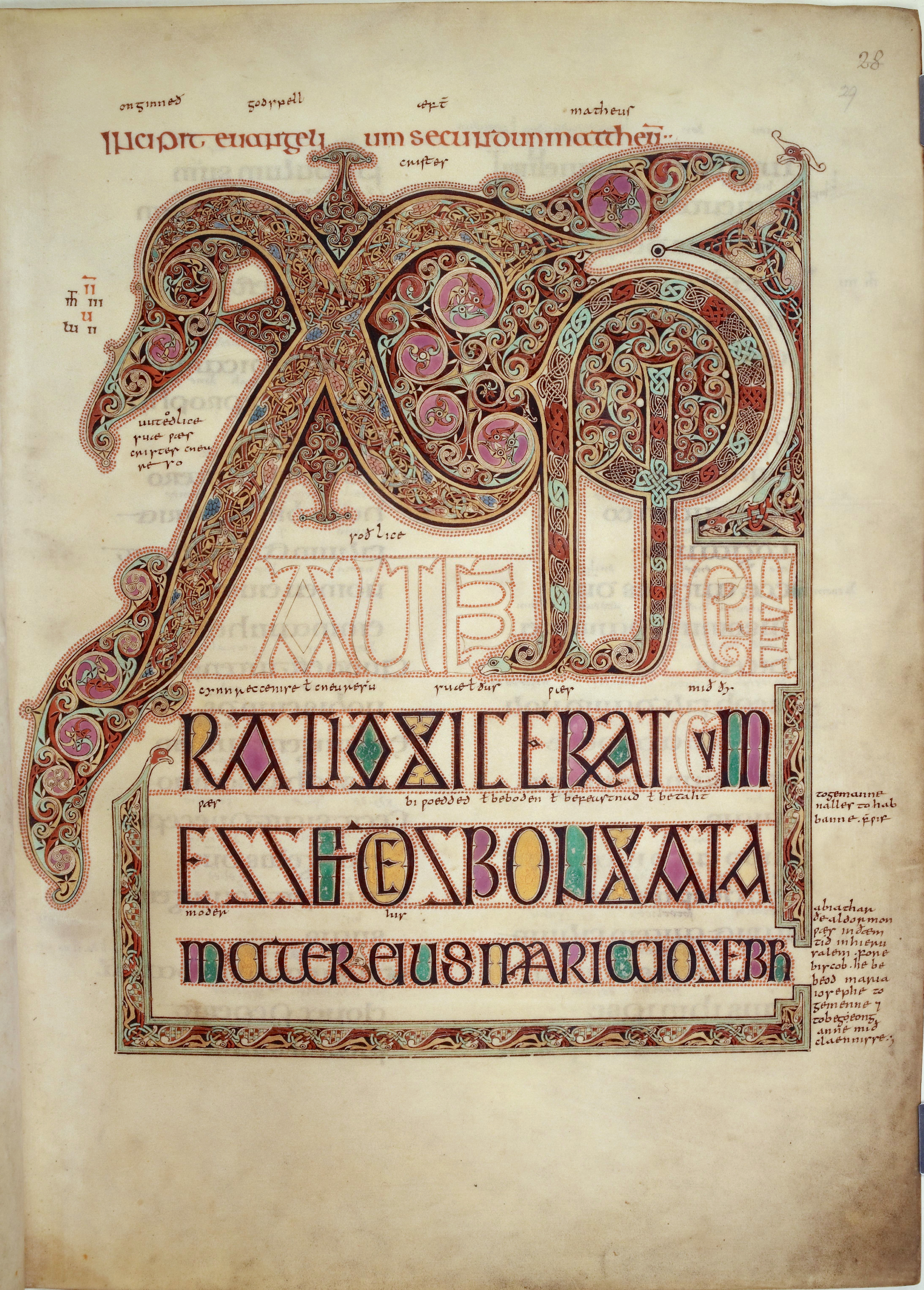

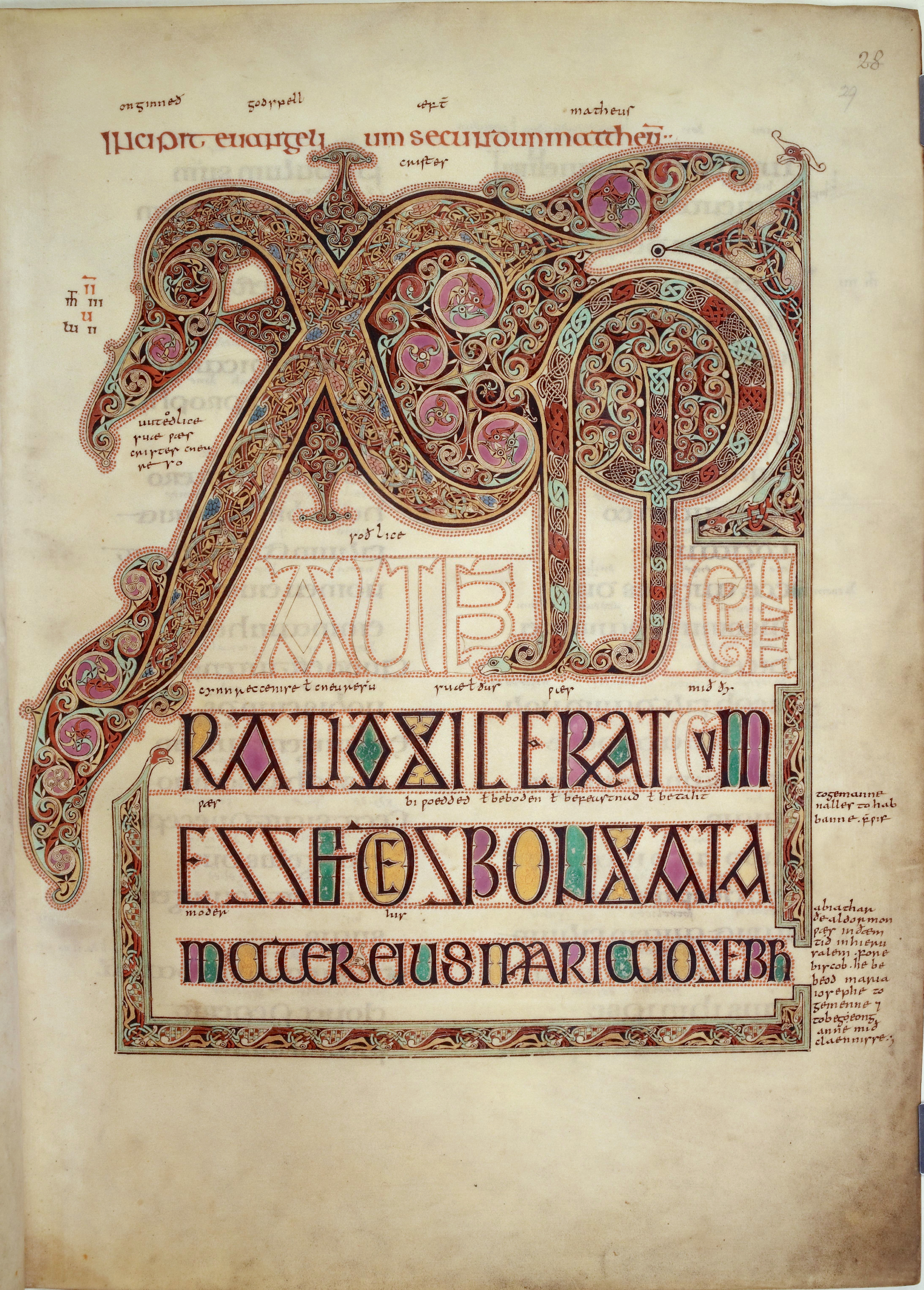

In 635 Aidan of Lindisfarne, Aidan, an Irish monk from

Iona

Iona (; gd, Ì Chaluim Chille (IPA: �iːˈxaɫ̪ɯimˈçiʎə, sometimes simply ''Ì''; sco, Iona) is a small island in the Inner Hebrides, off the Ross of Mull on the western coast of Scotland. It is mainly known for Iona Abbey, though there ...

, chose the Lindisfarne, Isle of Lindisfarne to establish a monastery which was close to King Oswald of Northumbria, Oswald's main fortress of Bamburgh. He had been at the monastery in Iona when Oswald asked to be sent a mission to Christianise the Northumbria, Kingdom of Northumbria from their native Anglo-Saxon paganism. Oswald had probably chosen Iona because after his father had been killed he had fled into south-west Scotland and had encountered Christianity, and had returned determined to make Northumbria Christian. Aidan achieved great success in spreading the Christian faith, and since Aidan could not speak English and Oswald had learned Irish during his exile, Oswald acted as Aidan's interpreter when the latter was preaching. Later, Northumberland's patron saint, Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, Saint Cuthbert, was an abbot of the monastery, and then Bishop of Lindisfarne. An anonymous life of Cuthbert written at Lindisfarne is the oldest extant piece of English historical writing, and in his memory a gospel (known as the St Cuthbert Gospel) was placed in his coffin. The decorated leather bookbinding is the oldest intact European binding.

In 664, the Synod of Whitby was convened and established Roman practice as opposed to Irish practice (in style of tonsure and dates of Easter) as the norm in Northumbria, and thus "brought the Northumbrian church into the mainstream of Roman culture." The episcopal seat of Northumbria was transferred from Lindisfarne to York. Wilfrid, chief advocate for the Roman position, later became Bishop of Northumbria, while Colmán and the Ionan supporters, who did not change their practices, withdrew to Iona.

Middle Anglo-Saxon history (660–899)

By 660, the political map of Tees–Exe line, Lowland Britain had developed with smaller territories coalescing into kingdoms, and from this time larger kingdoms started dominating the smaller kingdoms. The development of kingdoms, with a particular king being recognised as an overlord, developed out of an early loose structure that, Higham believes, is linked back to the original ''feodus''. The traditional name for this period is the Heptarchy, which has not been used by scholars since the early 20th century

as it gives the impression of a single political structure and does not afford the "opportunity to treat the history of any one kingdom as a whole".

[Keynes, Simon. "England, 700–900." The New Cambridge Medieval History 2 (1995): 18–42.] Simon Keynes suggests that the 8th and 9th century was a period of economic and social flourishing which created stability both below the River Thames, Thames and above the Humber.

Mercian supremacy (626–821)

Middle-lowland Britain was known as the place of the ''Mierce'', the border or frontier folk, in Latin Mercia. Mercia was a diverse area of tribal groups, as shown by the Tribal Hidage; the peoples were a mixture of Brittonic speaking peoples and "Anglo-Saxon" pioneers and their early leaders had Brittonic names, such as Penda of Mercia, Penda.

[Yorke, Barbara. Kings and kingdoms of early Anglo-Saxon England. Routledge, 2002: p101] Although Penda does not appear in Bede's list of great overlords, it would appear from what Bede says elsewhere that he was dominant over the southern kingdoms. At the time of the battle of the river Winwæd, thirty ''duces regii'' (royal generals) fought on his behalf. Although there are many gaps in the evidence, it is clear that the seventh-century Mercian kings were formidable rulers who were able to exercise a wide-ranging overlordship from their The Midlands, Midland base.

Mercian military success was the basis of their power; it succeeded against not only 106 kings and kingdoms by winning set-piece battles, but by ruthlessly ravaging any area foolish enough to withhold tribute. There are a number of casual references scattered throughout the

Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom o ...

's history to this aspect of Mercian military policy. Penda is found ravaging Northumbria as far north as Bamburgh and only a miraculous intervention from Aidan prevents the complete destruction of the settlement. In 676 Æthelred of Mercia, Æthelred conducted a similar ravaging in Kent and caused such damage in the Rochester, Kent, Rochester diocese that two successive bishops gave up their position because of lack of funds. In these accounts there is a rare glimpse of the realities of early Anglo-Saxon overlordship and how a widespread overlordship could be established in a relatively short period. By the middle of the 8th century, other kingdoms of southern Britain were also affected by Mercian expansionism. The East Saxons seem to have lost control of London, Middlesex and Hertfordshire to Æthelbald, although the East Saxon homelands do not seem to have been affected, and the East Saxon dynasty continued into the ninth century. The Mercian influence and reputation reached its peak when, in the late 8th century, the most powerful European ruler of the age, the Frankish king Charlemagne, recognised Offa of Mercia, the Mercian King Offa's power and accordingly treated him with respect, even if this could have been just flattery.

Learning and monasticism (660–793)

Michael Drout calls this period the "Golden Age", when learning flourished with a renaissance in classical knowledge. The growth and popularity of monasticism was not an entirely internal development, with influence from the continent shaping Anglo-Saxon monastic life. In 669 Theodore of Tarsus, Theodore, a Greek-speaking monk originally from Tarsus in Asia Minor, arrived in Britain List of archbishops of Canterbury, to become the eighth Archbishop of Canterbury. He was joined the following year by his colleague Hadrian, a Latin-speaking African by origin and former abbot of a monastery in Campania (near Naples). One of their first tasks at Canterbury was the establishment of a school; and according to Bede (writing some sixty years later), they soon "attracted a crowd of students into whose minds they daily poured the streams of wholesome learning". As evidence of their teaching, Bede reports that some of their students, who survived to his own day, were as fluent in Greek and Latin as in their native language. Bede does not mention Aldhelm in this connection; but we know from a letter addressed by Aldhelm to Hadrian that he too must be numbered among their students.

Aldhelm wrote in elaborate and grandiloquent and very difficult Latin, which became the dominant style for centuries. Michael Drout states "Aldhelm wrote Latin hexameters better than anyone before in England (and possibly better than anyone since, or at least up until John Milton). His work showed that scholars in England, at the very edge of Europe, could be as learned and sophisticated as any writers in Europe." During this period, the wealth and power of the monasteries increased as elite families, possibly out of power, turned to monastic life.

Anglo-Saxon monasticism developed the unusual institution of the "double monastery", a house of monks and a house of nuns, living next to each other, sharing a church but never mixing, and living separate lives of celibacy. These double monasteries were presided over by abbesses, who became some of the most powerful and influential women in Europe. Double monasteries which were built on strategic sites near rivers and coasts, accumulated immense wealth and power over multiple generations (their inheritances were not divided) and became centers of art and learning.

While Aldhelm was doing his work in Malmesbury, far from him, up in the North of England, Bede was writing a large quantity of books, gaining a reputation in Europe and showing that the English could write history and theology, and do astronomical computation (for the dates of Easter, among other things).

West Saxon hegemony and the Anglo-Scandinavian Wars (793–878)

During the 9th century,

Wessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

rose in power, from the foundations laid by Egbert of Wessex, King Egbert in the first quarter of the century to the achievements of Alfred the Great, King Alfred the Great in its closing decades. The outlines of the story are told in the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'', though the annals represent a West Saxon point of view. On the day of Egbert's succession to the kingdom of Wessex, in 802, a Mercian ealdorman from the province of the Hwicce had crossed the border at Kempsford, with the intention of mounting a raid into northern Wiltshire; the Mercian force was met by the local ealdorman, "and the people of Wiltshire had the victory". In 829, Egbert went on, the chronicler reports, to conquer "the kingdom of the Mercians and everything south of the Humber".

[Whitelock, Dorothy, ed. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1965.] It was at this point that the chronicler chooses to attach Egbert's name to Bede's list of seven overlords, adding that "he was the eighth king who was Bretwalda". Simon Keynes suggests Egbert's foundation of a 'bipartite' kingdom is crucial as it stretched across southern England, and it created a working alliance between the West Saxon dynasty and the rulers of the Mercians. In 860, the eastern and western parts of the southern kingdom were united by agreement between the surviving sons of Æthelwulf of Wessex, King Æthelwulf, though the union was not maintained without some opposition from within the dynasty; and in the late 870s King Alfred gained the submission of the Mercians under their ruler Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians, Æthelred, who in other circumstances might have been styled a king, but who under the Alfredian regime was regarded as the 'ealdorman' of his people.

The wealth of the monasteries and the success of Anglo-Saxon society attracted the attention of people from mainland Europe, mostly Danes and Norwegians. Because of the plundering raids that followed, the raiders attracted the name

Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

– from the Old Norse ''víkingr'' meaning an expedition – which soon became used for the raiding activity or piracy reported in western Europe. In 793, Lindisfarne was raided and while this was not the first raid of its type it was the most prominent. In 794, Jarrow, the monastery where Bede wrote, was attacked; in 795 Iona was attacked; and in 804 the nunnery at Lyminge Kent was granted refuge inside the walls of Canterbury. Sometime around 800, a Reeve from Portland in Wessex was killed when he mistook some raiders for ordinary traders.

Viking raids continued until in 850, then the ''Chronicle'' says: "The heathen for the first time remained over the winter". The fleet does not appear to have stayed long in England, but it started a trend which others subsequently followed. In particular, the army which arrived in 865 remained over many winters, and part of it later settled what became known as the

Danelaw

The Danelaw (, also known as the Danelagh; ang, Dena lagu; da, Danelagen) was the part of England in which the laws of the Danes held sway and dominated those of the Anglo-Saxons. The Danelaw contrasts with the West Saxon law and the Mercian ...

. This was the "Great Heathen Army, Great Army", a term used by the ''Chronicle'' in England and by Adrevald of Fleury on the Continent. The invaders were able to exploit the feuds between and within the various kingdoms and to appoint puppet kings, such as Ceolwulf in Mercia in 873 and perhaps others in Northumbria in 867 and East Anglia in 870.

The third phase was an era of settlement; however, the "Great Army" went wherever it could find the richest pickings, crossing the English Channel when faced with resolute opposition, as in England in 878, or with famine, as on the Continent in 892.

By this stage, the Vikings were assuming ever increasing importance as catalysts of social and political change. They constituted the common enemy, making the English more conscious of a national identity which overrode deeper distinctions; they could be perceived as an instrument of divine punishment for the people's sins, raising awareness of a collective Christian identity; and by 'conquering' the kingdoms of the East Angles, the Northumbrians and the Mercians, they created a vacuum in the leadership of the English people.

Danish settlement continued in Mercia in 877 and East Anglia in 879—80 and 896. The rest of the army meanwhile continued to harry and plunder on both sides of the Channel, with new recruits evidently arriving to swell its ranks, for it clearly continued to be a formidable fighting force.

At first, Alfred responded by the offer of repeated tribute payments. However, after a decisive victory at Edington in 878, Alfred offered vigorous opposition. He established a chain of fortresses across the south of England, reorganised the army, "so that always half its men were at home, and half out on service, except for those men who were to garrison the burhs",

and in 896 ordered a new type of craft to be built which could oppose the Viking longships in shallow coastal waters. When the Vikings returned from the Continent in 892, they found they could no longer roam the country at will, for wherever they went they were opposed by a local army. After four years, the Scandinavians therefore split up, some to settle in Northumbria and East Anglia, the remainder to try their luck again on the Continent.

King Alfred and the rebuilding (878–899)

More important to Alfred than his military and political victories were his religion, his love of learning, and his spread of writing throughout England. Keynes suggests Alfred's work laid the foundations for what really made England unique in all of medieval Europe from around 800 until 1066.

Thinking about how learning and culture had fallen since the last century, King Alfred wrote:

Alfred knew that literature and learning, both in English and in Latin, were very important, but the state of learning was not good when Alfred came to the throne. Alfred saw kingship as a priestly office, a shepherd for his people. One book that was particularly valuable to him was Pope Gregory I, Gregory the Great's ''Cura Pastoralis'' (Pastoral Care). This is a priest's guide on how to care for people. Alfred took this book as his own guide on how to be a good king to his people; hence, a good king to Alfred increases literacy. Alfred translated this book himself and explains in the preface:

What is presumed to be one of these "æstel" (the word only appears in this one text) is the gold, rock crystal and enamel Alfred Jewel, discovered in 1693, which is assumed to have been fitted with a small rod and used as a pointer when reading. Alfred provided functional patronage, linked to a social programme of vernacular literacy in England, which was unprecedented.

This began a growth in charters, law, theology and learning. Alfred thus laid the foundation for the great accomplishments of the tenth century and did much to make the vernacular more important than Latin in Anglo-Saxon culture.

Late Anglo-Saxon history (899–1066)

A framework for the momentous events of the 10th and 11th centuries is provided by the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle''. However charters, law-codes and coins supply detailed information on various aspects of royal government, and the surviving works of Anglo-Latin and vernacular literature, as well as the numerous manuscripts written in the 10th century, testify in their different ways to the vitality of ecclesiastical culture. Yet as Keynes suggests "it does not follow that the 10th century is better understood than more sparsely documented periods".

Reform and formation of England (899–978)

During the course of the 10th century, the West Saxon kings extended their power first over Mercia, then into the southern Danelaw, and finally over Northumbria, thereby imposing a semblance of political unity on peoples, who nonetheless would remain conscious of their respective customs and their separate pasts. The prestige, and indeed the pretensions, of the monarchy increased, the institutions of government strengthened, and kings and their agents sought in various ways to establish social order.

[Keynes, Simon. "Edward, King of the Anglo-Saxons."." Edward the Elder: 899 924 (2001): 40–66.] This process started with Edward the Elder – who with his sister, Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians, initially, charters reveal, encouraged people to purchase estates from the Danes, thereby to reassert some degree of English influence in territory which had fallen under Danish control. David Dumville suggests that Edward may have extended this policy by rewarding his supporters with grants of land in the territories newly conquered from the Danes and that any charters issued in respect of such grants have not survived. When Athelflæd died, Mercia was absorbed by Wessex. From that point on there was no contest for the throne, so the house of Wessex became the ruling house of England.

Edward the Elder was succeeded by his son

Æthelstan

Æthelstan or Athelstan (; ang, Æðelstān ; on, Aðalsteinn; ; – 27 October 939) was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 924 to 927 and King of the English from 927 to his death in 939. He was the son of King Edward the Elder and his first ...

, who Keynes calls the "towering figure in the landscape of the tenth century". His victory over a coalition of his enemies – Constantine II of Scotland, Constantine, King of the Scots; Owain ap Dyfnwal (fl. 934), Owain ap Dyfnwal, King of the Cumbrians; and Olaf Guthfrithson, King of Dublin – at the battle of Brunanburh, celebrated by a poem in the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'', opened the way for him to be hailed as the first king of England. Æthelstan's legislation shows how the king drove his officials to do their respective duties. He was uncompromising in his insistence on respect for the law. However this legislation also reveals the persistent difficulties which confronted the king and his councillors in bringing a troublesome people under some form of control. His claim to be "king of the English" was by no means widely recognised. The situation was complex: the Norse–Gaels, Hiberno-Norse rulers of Dublin still coveted their interests in the Scandinavian York, Danish kingdom of York; terms had to be made with the Scots, who had the capacity not merely to interfere in Northumbrian affairs, but also to block a line of communication between Dublin and York; and the inhabitants of northern Northumbria were considered a law unto themselves. It was only after twenty years of crucial developments following Æthelstan's death in 939 that a unified kingdom of England began to assume its familiar shape. However, the major political problem for Edmund I, Edmund and Eadred, who succeeded Æthelstan, remained the difficulty of subjugating the north.

[Dumville, David N. "Between Alfred the Great and Edgar the Peacemaker: Æthelstan, First King of England." Wessex and England from Alfred to Edgar (1992): 141–171.] In 959 Edgar the Peaceful, Edgar is said to have "succeeded to the kingdom both in Wessex and in Mercia and in Northumbria, and he was then 16 years old" (ASC, version 'B', 'C'), and is called "the Peacemaker".

By the early 970s, after a decade of Edgar's 'peace', it may have seemed that the kingdom of England was indeed made whole. In his formal address to the gathering at Winchester the king urged his bishops, abbots and abbesses "to be of one mind as regards monastic usage . . . lest differing ways of observing the customs of one Rule and one country should bring their holy conversation into disrepute".

Athelstan's court had been an intellectual incubator. In that court were two young men named Dunstan and Æthelwold of Winchester, Æthelwold who were made priests, supposedly at the insistence of Athelstan, right at the end of his reign in 939.

[Gretsch, Mechthild. "Myth, Rulership, Church and Charters: Essays in Honour of Nicholas Brooks." The English Historical Review 124.510 (2009): 1136–1138.] Between 970 and 973 a council was held, under the aegis of Edgar, where a set of rules were devised that would be applicable throughout England. This put all the monks and nuns in England under one set of detailed customs for the first time. In 973, Edgar received a special second, 'imperial coronation' at Bath, and from this point England was ruled by Edgar under the strong influence of Dunstan, Athelwold, and Oswald of Worcester, Oswald, the Bishop of Worcester.

Æthelred and the return of the Scandinavians (978–1016)

The reign of King Æthelred the Unready witnessed the resumption of Viking raids on England, putting the country and its leadership under strains as severe as they were long sustained. Raids began on a relatively small scale in the 980s but became far more serious in the 990s, and brought the people to their knees in 1009–12, when a large part of the country was devastated by the army of Thorkell the Tall. It remained for Swein Forkbeard, king of Denmark, to conquer the kingdom of England in 1013–14, and (after Æthelred's restoration) for his son Cnut to achieve the same in 1015–16. The tale of these years incorporated in the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' must be read in its own right, and set beside other material which reflects in one way or another on the conduct of government and warfare during Æthelred's reign. It is this evidence which is the basis for Keynes's view that the king lacked the strength, judgement and resolve to give adequate leadership to his people in a time of grave national crisis; who soon found out that he could rely on little but the treachery of his military commanders; and who, throughout his reign, tasted nothing but the ignominy of defeat. The raids exposed tensions and weaknesses which went deep into the fabric of the late Anglo-Saxon state, and it is apparent that events proceeded against a background more complex than the chronicler probably knew. It seems, for example, that the death of Bishop Æthelwold in 984 had precipitated further reaction against certain ecclesiastical interests; that by 993 the king had come to regret the error of his ways, leading to a period when the internal affairs of the kingdom appear to have prospered.

The increasingly difficult times brought on by the Viking attacks are reflected in both Ælfric of Eynsham, Ælfric's and Wulfstan the Cantor, Wulfstan's works, but most notably in Wulfstan's fierce rhetoric in the ''Sermo Lupi ad Anglos'', dated to 1014. Malcolm Godden suggests that ordinary people saw the return of the Vikings as the imminent "expectation of the apocalypse," and this was given voice in Ælfric and Wulfstan writings, which is similar to that of Gildas and Bede. Raids were taken as signs of God punishing his people; Ælfric refers to people adopting the customs of the Danish and exhorts people not to abandon the native customs on behalf of the Danish ones, and then requests a "brother Edward" to try to put an end to a "shameful habit" of drinking and eating in the outhouse, which some of the countrywomen practised at beer parties.

In April 1016, Æthelred died of illness, leaving his son and successor Edmund Ironside to defend the country. The final struggles were complicated by internal dissension, and especially by the treacherous acts of Ealdorman Eadric of Mercia, who opportunistically changed sides to Cnut's party. After the defeat of the English in the Battle of Assandun in October 1016, Edmund and Cnut agreed to divide the kingdom so that Edmund would rule Wessex and Cnut Mercia, but Edmund died soon after his defeat in November 1016, making it possible for Cnut to seize power over all England.

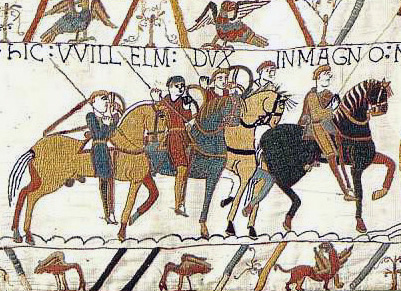

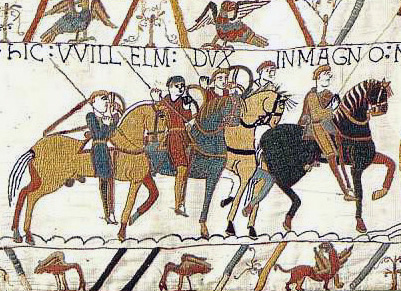

Conquest of England: Danes, Norwegians and Normans (1016–1066)

In the 11th century, there were three conquests: one by Cnut in 1016; the second was an unsuccessful attempt of Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066; and the third was conducted by William the Conqueror, William of Normandy in 1066. The consequences of each conquest changed the Anglo-Saxon culture. Politically and chronologically, the texts of this period are not Anglo-Saxon; linguistically, those written in English (as opposed to Latin or French, the other official written languages of the period) moved away from the late West Saxon standard that is called "Old English". Yet neither are they "Middle English"; moreover, as Treharne explains, for around three-quarters of this period, "there is barely any 'original' writing in English at all". These factors have led to a gap in scholarship, implying a discontinuity either side of the Norman Conquest, however this assumption is being challenged.

At first sight, there would seem little to debate. Cnut appeared to have adopted wholeheartedly the traditional role of Anglo-Saxon kingship. However an examination of the laws, homilies, wills, and charters dating from this period suggests that as a result of widespread aristocratic death and the fact that Cnut did not systematically introduce a new landholding class, major and permanent alterations occurred in the Saxon social and political structures. Eric John remarks that for Cnut "the simple difficulty of exercising so wide and so unstable an empire made it necessary to practise a delegation of authority against every tradition of English kingship". The disappearance of the aristocratic families which had traditionally played an active role in the governance of the realm, coupled with Cnut's choice of thegnly advisors, put an end to the balanced relationship between monarchy and aristocracy so carefully forged by the West Saxon Kings.

Edward the Confessor, Edward became king in 1042, and given his upbringing might have been considered a Norman by those who lived across the English Channel. Following Cnut's reforms, excessive power was concentrated in the hands of the rival houses of Leofric, Earl of Mercia, Leofric of Mercia and Godwin, Earl of Wessex, Godwine of Wessex. Problems also came for Edward from the resentment caused by the king's introduction of Norman friends. A crisis arose in 1051 when Godwine defied the king's order to punish the men of Dover, who had resisted an attempt by Eustace II, Count of Boulogne, Eustace of Boulogne to quarter his men on them by force.

[Maddicott, J. R. (2004). "Edward the Confessor's Return to England in 1041". English Historical Review (Oxford University Press) CXIX (482): 650–666.] The support of Earl Leofric and Earl Siward enabled Edward to secure the outlawry of Godwine and House of Godwin, his sons; and William of Normandy paid Edward a visit during which Edward may have promised William succession to the English throne, although this Norman claim may have been mere propaganda. Godwine and his sons came back the following year with a strong force, and the magnates were not prepared to engage them in civil war but forced the king to make terms. Some unpopular Normans were driven out, including Robert of Jumièges, Archbishop Robert, whose archbishopric was given to Stigand; this act supplied an excuse for the Papal support of William's cause.

The fall of England and the Norman Conquest is a multi-generational, multi-family succession problem caused in great part by Athelred's incompetence. By the time William of Normandy, sensing an opportunity, landed his invading force in 1066, the elite of Anglo-Saxon England had changed, although much of the culture and society had stayed the same.

After the Norman Conquest

Following the Norman conquest of England, Norman conquest, many of the Anglo-Saxon nobility were either exiled or had joined the ranks of the peasantry. It has been estimated that only about 8% of the land was under Anglo-Saxon control by 1087. In 1086, only four major Anglo-Saxon landholders still held their lands. However, the survival of Anglo-Saxon heiresses was significantly greater. Many of the next generation of the nobility had English mothers and learnt to speak English at home. Some Anglo-Saxon nobles fled to Scotland, Ireland, and Scandinavia.

[From Norman Conquest to Magna Carta: England, 1066–1215, pp.13,14]

Christopher Daniell, 2003, The Byzantine Empire became a popular destination for many Anglo-Saxon soldiers, as it was in need of mercenaries.

[Western travellers to Constantinople: the West and Byzantium, 962–1204, pp. 140,141]

Krijna Nelly Ciggaar, 1996, The Anglo-Saxons became the predominant element in the elite Varangian Guard, hitherto a largely Germanic peoples, North Germanic unit, from which the emperor's bodyguard was drawn and continued to serve the empire until the early 15th century. However, the population of England at home remained largely Anglo-Saxon; for them, little changed immediately except that their Anglo-Saxon lord was replaced by a Norman lord.

The chronicler Orderic Vitalis, who was the product of an Anglo-Norman marriage, writes: "And so the English groaned aloud for their lost liberty and plotted ceaselessly to find some way of shaking off a yoke that was so intolerable and unaccustomed". The inhabitants of the North and Scotland never warmed to the Normans following the Harrying of the North (1069–1070), where William, according to the ''Anglo Saxon Chronicle'' utterly "ravaged and laid waste that shire".

Many Anglo-Saxon people needed to learn Norman language, Norman French to communicate with their rulers, but it is clear that among themselves they kept speaking Old English, which meant that England was in an interesting tri-lingual situation: Anglo-Saxon for the common people, Latin for the Church, and Norman French for the administrators, the nobility, and the law courts. In this time, and because of the cultural shock of the Conquest, Anglo-Saxon began to change very rapidly, and by 1200 or so, it was no longer Anglo-Saxon English, but early Middle English. But this language had deep roots in Anglo-Saxon, which was being spoken much later than 1066. Research has shown that a form of Anglo-Saxon was still being spoken, and not merely among uneducated peasants, into the thirteenth century in the West Midlands.

[Drout, Michael DC, ed. JRR Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and critical assessment. Routledge, 2006.] This was J.R.R. Tolkien's major scholarly discovery when he studied a group of texts written in early Middle English called the Katherine Group. Tolkien noticed that a subtle distinction preserved in these texts indicated that Old English had continued to be spoken far longer than anyone had supposed.

Old English had been a central mark of the Anglo-Saxon cultural identity. With the passing of time, however, and particularly following the Norman conquest of England, this language changed significantly, and although some people (for example the scribe known as the Tremulous Hand of Worcester) could still read Old English into the thirteenth century, it fell out of use and the texts became useless. The Exeter Book, for example, seems to have been used to press gold leaf and at one point had a pot of fish-based glue sitting on top of it. For Michael Drout this symbolises the end of the Anglo-Saxons.

Life and society

The larger narrative, seen in the history of Anglo-Saxon England, is the continued mixing and integration of various disparate elements into one Anglo-Saxon people. The outcome of this mixing and integration was a continuous re-interpretation by the Anglo-Saxons of their society and worldview, which Heinreich Härke calls a "complex and ethnically mixed society".

[Härke, Heinrich. "Changing symbols in a changing society. The Anglo-Saxon weapon burial rite in the seventh century." The Age of Sutton Hoo. The Seventh Century in North-Western Europe, ed. Martin OH Carver (Woodbridge 1992) (1992): 149–165.]

Kingship and kingdoms

The development of Anglo-Saxon kingship is little understood, but the model proposed by York considered the development of kingdoms and writing down of the oral law-codes to be linked to a progression towards leaders providing Mund (law), mund and receiving recognition. These leaders who developed in the sixth century were able to seize the initiative and to establish a position of power for themselves and their successors. Anglo-Saxon leaders, unable to tax and coerce followers, extracted surplus by raiding and collecting food renders and 'prestige goods'. The later sixth century saw the end of a 'prestige goods' economy, as evidenced by the decline of accompanied burial, and the appearance of the first 'princely' graves and high-status settlements. The ship burial in mound one at Sutton Hoo (Suffolk) is the most widely known example of a 'princely' burial, containing lavish metalwork and feasting equipment, and possibly representing the burial place of King Raedwald of East Anglia. These centres of trade and production reflect the increased socio-political stratification and wider territorial authority which allowed seventh-century elites to extract and redistribute surpluses with far greater effectiveness than their sixth-century predecessors would have found possible. Anglo-Saxon society, in short, looked very different in 600 than it did a hundred years earlier.

By 600, the establishment of the first Anglo-Saxon 'emporia'(alternatively 'wics') appears to have been in process. There are only four major archaeologically attested -wich town, wics in England - London, Ipswich, York, and Hamwic. These were originally interpreted by Hodges as methods of royal control over the import of prestige goods, rather than centre of actual trade-proper. Despite archaeological evidence of royal involvement, emporia are now widely understood to represent genuine trade and exchange, alongside a return to urbanism. Bede's use of the term ''imperium'' has been seen as significant in defining the status and powers of the bretwaldas, in fact it is a word Bede used regularly as an alternative to ''regnum''; scholars believe this just meant the collection of tribute. Oswiu's extension of overlordship over the Picts and Scots is expressed in terms of making them tributary. Military overlordship could bring great short-term success and wealth, but the system had its disadvantages. Many of the overlords enjoyed their powers for a relatively short period. Foundations had to be carefully laid to turn a tribute-paying under-kingdom into a permanent acquisition, such as Bernician absorption of Deira. The smaller kingdoms did not disappear without trace once they were incorporated into larger polities; on the contrary their territorial integrity was preserved when they became ealdormanries or, depending on size, parts of ealdormanries within their new kingdoms. An example of this tendency for later boundaries to preserve earlier arrangements is Sussex; the county boundary is essentially the same as that of the West Saxon shire and the Anglo-Saxon kingdom. The Witan, also called Witenagemot, was the council of kings; its essential duty was to advise the king on all matters on which he chose to ask its opinion. It attested his grants of land to churches or laymen, consented to his issue of new laws or new statements of ancient custom, and helped him deal with rebels and persons suspected of disaffection.