Andreas Joseph Hofmann on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Andreas Joseph Hofmann (14 July 1752 – 6 September 1849) was a German philosopher and revolutionary active in the

Andreas Joseph Hofmann (14 July 1752 – 6 September 1849) was a German philosopher and revolutionary active in the

Hofmann was born in

Hofmann was born in

In 1784, Hofmann was made Chair of Philosophy in

In 1784, Hofmann was made Chair of Philosophy in  Two days later, Hofmann helped found the Mainz

Two days later, Hofmann helped found the Mainz

When the republic ended after the siege of Mainz, Hofmann was able to leave the city with the retreating French troops and went into exile in

When the republic ended after the siege of Mainz, Hofmann was able to leave the city with the retreating French troops and went into exile in

Andreas Joseph Hofmann (14 July 1752 – 6 September 1849) was a German philosopher and revolutionary active in the

Andreas Joseph Hofmann (14 July 1752 – 6 September 1849) was a German philosopher and revolutionary active in the Republic of Mainz

The Republic of Mainz was the first democratic state in the current German territoryThe short-lived republic is often ignored in identifying the "first German democracy", in favour of the Weimar Republic; e.g. "the failure of the first German ...

. As Chairman of the Rhenish-German National Convention, the earliest parliament in Germany based on the principle of popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the authority of a state and its government are created and sustained by the consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. Popular sovereignty, being a principle, does not imply any ...

, he proclaimed the first republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

an state in Germany, the ''Rhenish-German Free State'', on 18 March 1793. A strong supporter of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

, he argued for an accession of all German territory west of the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

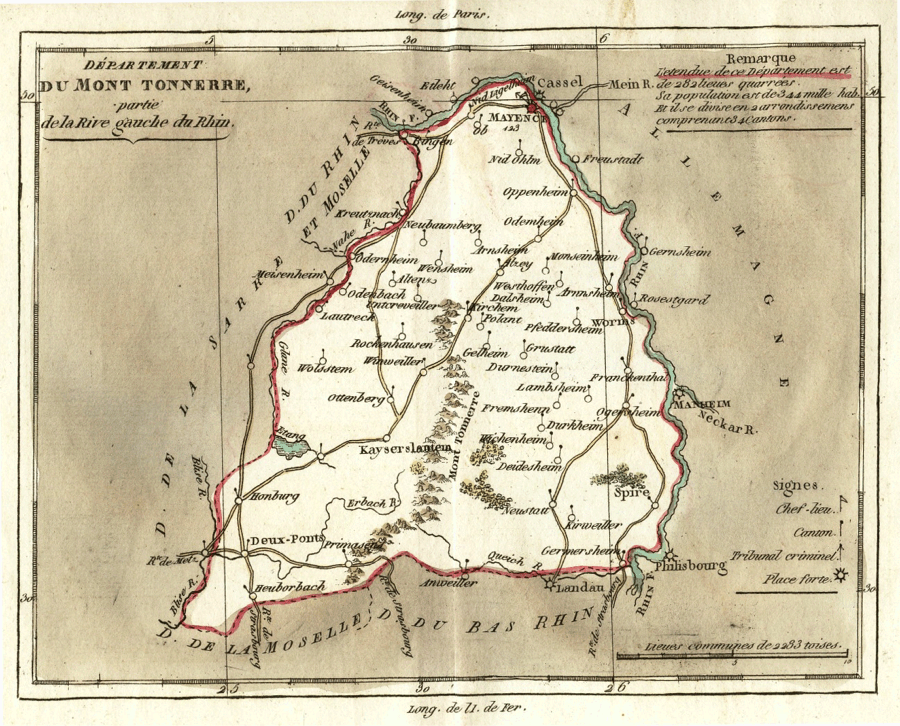

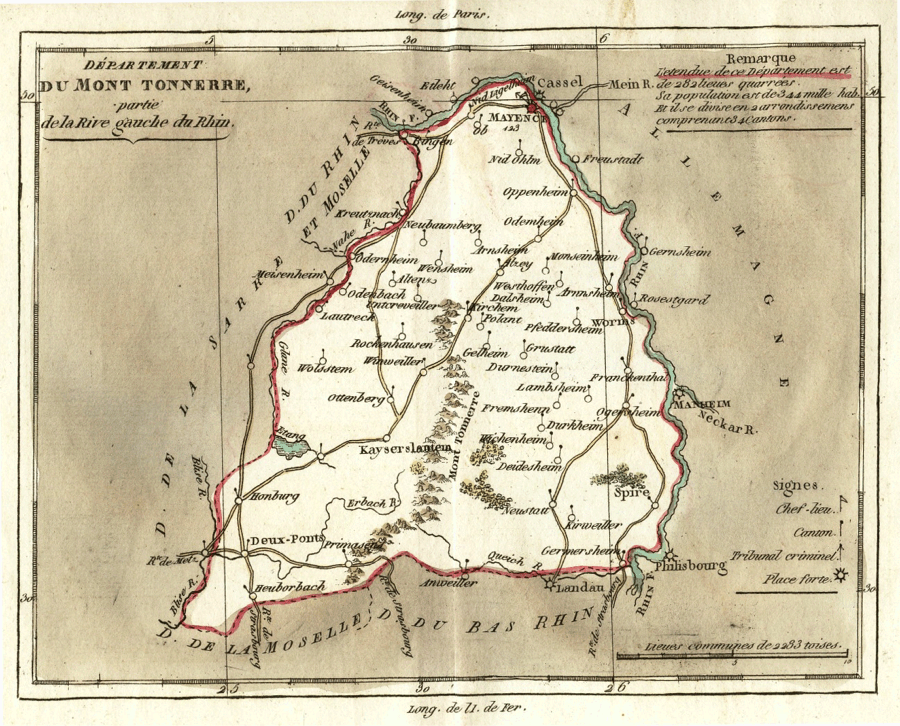

and served in the administration of the department Mont-Tonnerre

Mont-Tonnerre was a department of the First French Republic and later the First French Empire in present-day Germany. It was named after the highest point in the Palatinate, the ''Donnersberg'' ("Thunder Mountain", possibly referring to Donar, ...

under the French Directory

The Directory (also called Directorate, ) was the governing five-member committee in the French First Republic from 2 November 1795 until 9 November 1799, when it was overthrown by Napoleon, Napoleon Bonaparte in the Coup of 18 Brumaire and r ...

and the French Consulate

The Consulate (french: Le Consulat) was the top-level Government of France from the fall of the Directory in the coup of 18 Brumaire on 10 November 1799 until the start of the Napoleonic Empire on 18 May 1804. By extension, the term ''The Con ...

.

Early life and education

Zell am Main

Zell am Main is a municipality in the district of Würzburg in Bavaria in Germany, situated on the river Main.

Notable people

* Andreas Friedrich Bauer

* Andreas Joseph Fahrmann

* Andreas Joseph Hofmann

* Abraham Rice

Abraham Joseph Rice (bor ...

near Würzburg

Würzburg (; Main-Franconian: ) is a city in the region of Franconia in the north of the German state of Bavaria. Würzburg is the administrative seat of the ''Regierungsbezirk'' Lower Franconia. It spans the banks of the Main River.

Würzburg is ...

as the son of a surgeon

In modern medicine, a surgeon is a medical professional who performs surgery. Although there are different traditions in different times and places, a modern surgeon usually is also a licensed physician or received the same medical training as ...

. After the early death of his parents, he was educated by his uncle Fahrmann, likely Andreas Joseph Fahrmann

Andreas Joseph Fahrmann (8 November 1742 - 6 February 1802) was a German theologian and cleric.

Fahrmann was born in Zell am Main near Würzburg, in the Prince-Bishopric of Würzburg. He was ordained as a deacon in 1764 and as a priest in 1765. ...

(1742-1802), professor of moral theology

Ethics involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior.''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy''"Ethics"/ref> A central aspect of ethics is "the good life", the life worth living or life that is simply sati ...

at the University of Würzburg

The Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg (also referred to as the University of Würzburg, in German ''Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg'') is a public research university in Würzburg, Germany. The University of Würzburg is one of ...

and later auxiliary bishop in the Diocese of Würzburg

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associate ...

. After a one-year course in poetics

Poetics is the theory of structure, form, and discourse within literature, and, in particular, within poetry.

History

The term ''poetics'' derives from the Ancient Greek ποιητικός ''poietikos'' "pertaining to poetry"; also "creative" an ...

and rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate parti ...

at the Würzburg Jesuit college

The Jesuits (Society of Jesus) in the Catholic Church have founded and managed a number of educational institutions, including the notable secondary schools, colleges and universities listed here.

Some of these universities are in the United Stat ...

, Hofmann studied law at the University of Mainz

The Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (german: Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz) is a public research university in Mainz, Rhineland Palatinate, Germany, named after the printer Johannes Gutenberg since 1946. With approximately 32,000 stu ...

and at the University of Würzburg. In 1777 he moved to Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

to gain experience at the or Aulic Council

The Aulic Council ( la, Consilium Aulicum, german: Reichshofrat, literally meaning Court Council of the Empire) was one of the two supreme courts of the Holy Roman Empire, the other being the Imperial Chamber Court. It had not only concurrent juris ...

, one of the supreme courts of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

and became a in 1778. In Vienna, Hofmann was influenced by the enlightened principles of Josephinism

Josephinism was the collective domestic policies of Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor (1765–1790). During the ten years in which Joseph was the sole ruler of the Habsburg monarchy (1780–1790), he attempted to legislate a series of drastic reforms ...

. Besides philosophical publications such as (About the study of the history of philosophy), where Hofmann argued for the introduction of the history of philosophy as a subject in the Universities in Austria, following the example of Würzburg, he started writing articles for various journals and founded a theatre journal in 1781. His satirical articles caused conflict with the authorities, and instead of being given a position at the newly re-founded University of Lviv

The University of Lviv ( uk, Львівський університет, Lvivskyi universytet; pl, Uniwersytet Lwowski; german: Universität Lemberg, briefly known as the ''Theresianum'' in the early 19th century), presently the Ivan Franko Na ...

as had been originally envisioned, he was forced to leave Austria. He returned to Würzburg in 1783, and was soon after employed by the Prince

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. Th ...

of Hohenzollern-Hechingen

Hohenzollern-Hechingen was a small principality in southwestern Germany. Its rulers belonged to the Swabian branch of the Hohenzollern dynasty.

History

The County of Hohenzollern-Hechingen was created in 1576, upon the partition of the Coun ...

.

Professor and revolutionary in Mainz

In 1784, Hofmann was made Chair of Philosophy in

In 1784, Hofmann was made Chair of Philosophy in Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main (river), Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-we ...

as part of the progressive reforms of Elector Friedrich Karl von Erthal that had made the University of Mainz

The Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (german: Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz) is a public research university in Mainz, Rhineland Palatinate, Germany, named after the printer Johannes Gutenberg since 1946. With approximately 32,000 stu ...

one of the centres of Catholic Enlightenment. Like many other future members of the , he was a member of the secret society of the ''Illuminati

The Illuminati (; plural of Latin ''illuminatus'', 'enlightened') is a name given to several groups, both real and fictitious. Historically, the name usually refers to the Bavarian Illuminati, an Enlightenment-era secret society founded on ...

'' (under the name '' Aulus Persius'') but the Illuminati were outlawed in 1785 and the lodge dissolved soon after. Hofmann first taught History of Philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

until 1791, when he also became chair of natural law

Natural law ( la, ius naturale, ''lex naturalis'') is a system of law based on a close observation of human nature, and based on values intrinsic to human nature that can be deduced and applied independently of positive law (the express enacte ...

. Besides philosophy and law, Hofmann also was talented in languages. He was proficient in Latin, Ancient Greek, French, Italian, and English, and offered classes in English on Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

over many years. Among his students were Klemens von Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ; german: Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar Fürst von Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein (15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich or Prince Metternic ...

, who later became Chancellor of State of the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

and the architect of the reactionary European Restoration

The Concert of Europe was a general consensus among the Great Powers of 19th-century Europe to maintain the European balance of power, political boundaries, and spheres of influence. Never a perfect unity and subject to disputes and jockeying fo ...

, and , who became a leading liberal politician and member of the 1848 Frankfurt Parliament

The Frankfurt Parliament (german: Frankfurter Nationalversammlung, literally ''Frankfurt National Assembly'') was the first freely elected parliament for all German states, including the German-populated areas of Austria-Hungary, elected on 1 Ma ...

. As a liberal and progressive thinker, Hofmann supported the use of German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

instead of Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

in University lectures and in church. Eventually he became disillusioned with the pace of the reforms in Mainz and welcomed the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

from the start. As Hofmann declared his support of the ideas of the French Revolution openly in his lectures, he was soon spied on by the increasingly reactionary Mainz authorities, who had outlawed all criticism of state and religion on 10 September 1792. However, before the investigation of his activities had progressed beyond the questioning of his students, the archbishop and his court fled from the advancing French troops under General Custine, who arrived in Mainz on 21 October 1792.

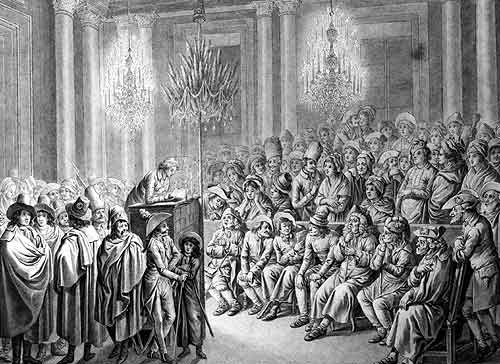

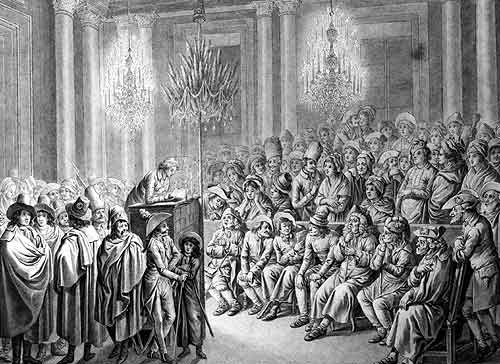

Two days later, Hofmann helped found the Mainz

Two days later, Hofmann helped found the Mainz Jacobin club

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = Pa ...

and became one of its most active members. A popular and powerful orator, he criticised both the old regime of the Elector and the French military government in his speeches, which were especially supported by the more radical students who idolised the incorruptible Hofmann. In late 1792, he published the , a revolutionary pamphlet criticising the old regime and its instrumentalisation of religion to protect the absolutist order. Hofmann and his supporters called for official posts to be reserved for native born citizens. Hofmann lectured in the rural areas of the French occupied territory, Text on Wikisource. calling for support of the general elections in February and March 1793 which he helped organize.Schweigard, ''Die Liebe zur Freiheit'', p. 151 He was elected into the Rhenish-German National Convention as a representative of Mainz and became its president, beating Georg Forster

Johann George Adam Forster, also known as Georg Forster (, 27 November 1754 – 10 January 1794), was a German naturalist, ethnologist, travel writer, journalist and revolutionary. At an early age, he accompanied his father, Johann Reinhold F ...

in a contested election. On 18 March 1793 Hofmann declared the Rhenish-German Free State from the balcony of the Deutschhaus. Three days later, Hofmann signed the Convention's unanimously resolved decree asking for accession of the Free State to France. On 1 April 1793, Hofmann switched roles to become the president of the provisional administration.

French government official and later life

When the republic ended after the siege of Mainz, Hofmann was able to leave the city with the retreating French troops and went into exile in

When the republic ended after the siege of Mainz, Hofmann was able to leave the city with the retreating French troops and went into exile in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, where he headed a society of exiled Mainz republicans, the and was working towards an exchange of prisoners to free the German revolutionaries captured by the authorities. After a short service in the military, where he commanded an equestrian regiment that fought against insurgent royalists in the Vendée

Vendée (; br, Vande) is a department in the Pays de la Loire region in Western France, on the Atlantic coast. In 2019, it had a population of 685,442.

and was wounded several times, he was sent to England on espionage missions. However, at a Joseph Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions ...

concert in London on 2 June 1794, he was recognized and reported to the authorities by his former student Klemens Wenzel von Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ; german: Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar Fürst von Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein (15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich or Prince Metternic ...

. Hofmann went into hiding and returned to Paris via Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

, where he visited Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock

Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock (; 2 July 1724 – 14 March 1803) was a German poet. His best known work is the epic poem ''Der Messias'' ("The Messiah"). One of his major contributions to German literature was to open it up to exploration outside ...

. In Paris, he was made chief of the ''bureau des étrangers'' by the French Directory

The Directory (also called Directorate, ) was the governing five-member committee in the French First Republic from 2 November 1795 until 9 November 1799, when it was overthrown by Napoleon, Napoleon Bonaparte in the Coup of 18 Brumaire and r ...

. In his 1795 essay , he argued for the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

as natural Eastern border of France. When the incorporation of areas west of the Rhine into France had become a reality with the Treaty of Campo Formio

The Treaty of Campo Formio (today Campoformido) was signed on 17 October 1797 (26 Vendémiaire VI) by Napoleon Bonaparte and Count Philipp von Cobenzl as representatives of the French Republic and the Austrian monarchy, respectively. The treat ...

, Hofmann returned to Mainz, where he became part of the government of the new Mont-Tonnerre

Mont-Tonnerre was a department of the First French Republic and later the First French Empire in present-day Germany. It was named after the highest point in the Palatinate, the ''Donnersberg'' ("Thunder Mountain", possibly referring to Donar, ...

and was appointed by Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

as its (superior tax officer) in 1797,Schweigard, ''Die Liebe zur Freiheit'', p. 153 the only non-native French holding this office. In 1801, he was elected as a member of the Mainz city council and refused an appointment as a member of the of the French Consulate

The Consulate (french: Le Consulat) was the top-level Government of France from the fall of the Directory in the coup of 18 Brumaire on 10 November 1799 until the start of the Napoleonic Empire on 18 May 1804. By extension, the term ''The Con ...

. In 1803, he was forced to resign as after one of his subordinates had committed fraud, and 750,000 francs were missing from his coffers.

After Napoleon's defeat and the return of Mainz to German control, Hofmann moved to his late wife's estates in Winkel. While he was no longer active as a revolutionary, he was suspicious to the authorities as a Jacobin, and his house was searched in the 1830s. Hofmann spent his retirement pursuing activities such as breeding domestic canaries but became a somewhat famous figure among ''Vormärz

' (; English: ''pre-March'') was a period in the history of Germany preceding the 1848 March Revolution in the states of the German Confederation. The beginning of the period is less well-defined. Some place the starting point directly after the ...

'' liberals and was visited by intellectuals such as Hoffmann von Fallersleben

August Heinrich Hoffmann (, calling himself von Fallersleben, after his hometown; 2 April 179819 January 1874) was a German poet. He is best known for writing "Das Lied der Deutschen", whose third stanza is now the national anthem of Germany, an ...

and . He died on 6 September 1849, having witnessed the failure of the 1848 revolution

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

, and was buried without a Catholic funeral.

Family and legacy

Andreas Joseph Hofmann was the son of Anton Hofmann, a surgeon, and of Magdalena Fahrmann. In 1788, he married Catharina Josepha Rivora (1763-1799), the daughter of Peter Maria Rivora and Christina Schumann. They had three daughters, of which two died early. His daughter Charlotte Sturm died in 1850 and bequeathed most of her belongings to Charlotte Lehne, the granddaughter of Hofmann's student Friedrich Lehne. None of Hofmann's personal papers and correspondence have been preserved, and there is no known picture of him. Overall, there is far less known about Hofmann's life than about most of the other leading members of the Mainz Jacobin club. In 2018, a road in Winkel was named .Selected works

* * *Notable students

* (1775-1855) * (1771-1836) *Klemens von Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ; german: Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar Fürst von Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein (15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich or Prince Metternic ...

(1773-1859)

* (1771-1837)Schweigard, ''Die Liebe zur Freiheit'', p. 206

Notes

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hofmann, Andreas Joseph 1752 births 1849 deaths Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz alumni People from Würzburg (district) German philosophers German revolutionaries Spies of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars German male writers Jacobins