Ancient Roman Coinage on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Roman currency for most of

Roman currency for most of

Coinage proper was only introduced by the republican government c. 300 BC. The greatest city of the

Coinage proper was only introduced by the republican government c. 300 BC. The greatest city of the

Featuring the portrait of an individual on a coin, which became legal in 44 BC, caused the coin to be viewed as embodying the attributes of the individual portrayed. Cassius Dio wrote that following the death of

Featuring the portrait of an individual on a coin, which became legal in 44 BC, caused the coin to be viewed as embodying the attributes of the individual portrayed. Cassius Dio wrote that following the death of

The type of coins issued changed under the coinage reform of

The type of coins issued changed under the coinage reform of

online version of this Cohen's catalogue

* Greene, Kevin. ''Archaeology of the Roman Economy''. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1986. * Howgego, Christopher. ''Ancient History from Coins''. London: Routledge, 1995. * Jones, A. H. M. ''The Roman Economy: Studies in Ancient Economic and Administrative History''. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1974. * Melville Jones, John R., 'A Dictionary of Ancient Roman Coins', London, Spink 2003. * * * Salmon, E. Togo. ''Roman Coins and Public Life under the Empire''. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan Press, 1999. * Suarez, Rasiel. ''The Encyclopedia of Roman Imperial Coins''. Dirty Old Books, 2005. * Sutherland, C. H. V. ''Roman Coins''. New York: G. P. (Also published by Barrie and Jenkins in London in 1974 with ) * Van Meter, David. ''The Handbook of Roman Imperial Coins''. Laurion Press, 1990. * Vecchi, Italo. ''Italian Cast Coinage. A descriptive catalogue of the cast coinage of Rome and Italy.'' London Ancient Coins, London 2013. Hard bound in quarto format, 84 pages, 92 plates. * Modena Altieri, Ascanio. ''Vis et Mos. A compendium of symbologies and allegorical personifications in the imperial coinage from Augustus to Diocletian''. Florence, Porto Seguro Editore, 2022.

A Collection of Flavian coins

Currency Debasement and Social Collapse

Ludwig von Mises {{Authority control Numismatics Economic history of Italy Currency

Roman currency for most of

Roman currency for most of Roman history

The history of Rome includes the history of the city of Rome as well as the civilisation of ancient Rome. Roman history has been influential on the modern world, especially in the history of the Catholic Church, and Roman law has influenced ma ...

consisted of gold, silver, bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

, orichalcum and copper coinage. From its introduction to the Republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

, during the third century BC, well into Imperial times, Roman currency saw many changes in form, denomination, and composition. A persistent feature was the inflationary debasement and replacement of coins over the centuries. Notable examples of this followed the reforms of Diocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

. This trend continued into Byzantine times.

Due to the economic power and longevity of the Roman state, Roman currency was widely used throughout western Eurasia and northern Africa from classical times into the Middle Ages. It served as a model for the currencies of the Muslim caliphates and the European states during the Middle Ages and the Modern Era. Roman currency names survive today in many countries, such as the Arabic dinar

The dinar () is the principal currency unit in several countries near the Mediterranean Sea, and its historical use is even more widespread.

The modern dinar's historical antecedents are the gold dinar and the silver dirham, the main coin of ...

(from the '' denarius'' coin), the British pound

Pound or Pounds may refer to:

Units

* Pound (currency), a unit of currency

* Pound sterling, the official currency of the United Kingdom

* Pound (mass), a unit of mass

* Pound (force), a unit of force

* Rail pound, in rail profile

Symbols

* Po ...

, and the peso (both translations of the Roman '' libra'').

Authority to mint coins

The manufacture of coins in the Roman culture, dating from about the 4th century BC, significantly influenced later development of coin minting in Europe. The origin of the word "mint" is ascribed to the manufacture of silver coin at Rome in 269 BC near the temple of Juno Moneta. This goddess became the personification of money, and her name was applied both to money and to its place of manufacture. Roman mints were spread widely across the Empire, and were sometimes used for propaganda purposes. The populace often learned of a new Roman Emperor when coins appeared with the new emperor's portrait. Some of the emperors who ruled only for a short time made sure that a coin bore their image; Quietus, for example, ruled only part of the Roman Empire from 260 to 261 AD, and yet he issued thirteen coins bearing his image from three mints. The Romans cast their larger copper coins in clay moulds carrying distinctive markings, not because they did not know aboutstriking

Strike may refer to:

People

*Strike (surname)

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

*Airstrike, military strike by air forces on either a suspected ...

, but because it was not suitable for such large masses of metal.

Roman Republic: c. 500 – 27 BC

Roman adoption of metallic commodity money was a late development in monetary history.Bullion

Bullion is non-ferrous metal that has been refined to a high standard of elemental purity. The term is ordinarily applied to bulk metal used in the production of coins and especially to precious metals such as gold and silver. It comes from t ...

bars and ingots were used as money in Mesopotamia since the 7th millennium BC; and Greeks in Asia Minor had pioneered the use of coinage (which they employed in addition to other more primitive, monetary mediums of exchange) as early as the 7th century BC.

Coinage proper was only introduced by the republican government c. 300 BC. The greatest city of the

Coinage proper was only introduced by the republican government c. 300 BC. The greatest city of the Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia (, ; , , grc, Μεγάλη Ἑλλάς, ', it, Magna Grecia) was the name given by the Romans to the coastal areas of Southern Italy in the present-day Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania and Sicily; these re ...

region in southern Italy, and several other Italian cities, already had a long tradition of using coinage by this time and produced them in large quantities during the 4th century BC to pay for their wars against the inland Italian groups encroaching on their territory. For these reasons, the Romans would have certainly known about coinage systems long before their government actually introduced them. Eventually, the economic conditions of the Second Punic War forced the Romans to fully adopt a coinage system.

The type of money introduced by Rome was unlike that found elsewhere in the ancient Mediterranean. It combined a number of uncommon elements. One example is the large bronze bullion, the ' ( Latin for ''signed bronze''). It measured about and weighed around , being made out of a highly leaded tin bronze. Although similar metal currency bars had been produced in Italy and northern Etruscan areas, these had been made of ', an unrefined metal with a high iron content.

Along with the ''aes signatum'', the Roman state also issued a series of bronze and silver coins that emulated the styles of those produced in Greek cities. Burnett 1987. pp. 4–5. Produced using the manner of manufacture then utilised in Greek Naples, the designs of these early coins were also heavily influenced by Greek designs. Burnett 1987. p. 16.

The designs on the coinage of the Republican period displayed a "solid conservatism", usually illustrating mythical scenes or personifications of various gods and goddesses.

Imperial period: 27 BC – AD 476

Iconography

The imagery on coins took an important step whenJulius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

issued coins bearing his own portrait. While moneyers had earlier issued coins with portraits of ancestors, Caesar's was the third Roman coinage to feature the depiction of a living individual. Although living Romans had appeared on coinage before, in the words of Clare Rowan (2019) "The appearance of Caesar's portrait on Roman denarii in 44 BC is often seen as a revolutionary moment in Roman history..." The appearance of Julius Caesar implemented a new standard, and the tradition continued following Caesar's assassination

Julius Caesar, the Roman dictator, was assassinated by a group of senators on the Ides of March (15 March) of 44 BC during a meeting of the Senate at the Curia of Pompey of the Theatre of Pompey in Rome where the senators stabbed Caesar 23 ti ...

, although the Roman emperors from time to time also produced coins featuring the traditional deities and personifications found on earlier coins. The image of the emperor took on a special importance in the centuries that followed, because during the Empire the emperor embodied the state and its policies. The names of moneyers continued to appear on the coins until the middle of Augustus' reign. Although the duty of moneyers during the Empire is not known, since the position was not abolished, it is believed that they still had some influence over the imagery of the coins.

The main focus of the imagery during the Empire was on the portrait of the emperor. Coins were an important means of disseminating this image throughout the Empire. Coins often attempted to make the emperor appear god-like through associating the emperor with attributes normally seen in divinities, or emphasizing the special relationship between the emperor and a particular deity by producing a preponderance of coins depicting that deity. During his campaign against Pompey, Caesar issued a variety of types that featured images of either Venus or Aeneas, attempting to associate himself with his divine ancestors. An example of an emperor who went to an extreme in proclaiming divine status was Commodus

Commodus (; 31 August 161 – 31 December 192) was a Roman emperor who ruled from 177 to 192. He served jointly with his father Marcus Aurelius from 176 until the latter's death in 180, and thereafter he reigned alone until his assassination. ...

. In AD 192 , he issued a series of coins depicting his bust clad in a lion-skin (the usual depiction of Hercules) on the obverse, and an inscription proclaiming that he was the Roman incarnation of Hercules on the reverse. Although Commodus was excessive in his depiction of his image, this extreme case is indicative of the objective of many emperors in the exploitation of their portraits. While the emperor is by far the most frequent portrait on the obverse of coins, heirs apparent, predecessors, and other family members, such as empresses, were also featured. To aid in succession, the legitimacy of an heir was affirmed by producing coins for that successor. This was done from the time of Augustus till the end of the Empire.

Featuring the portrait of an individual on a coin, which became legal in 44 BC, caused the coin to be viewed as embodying the attributes of the individual portrayed. Cassius Dio wrote that following the death of

Featuring the portrait of an individual on a coin, which became legal in 44 BC, caused the coin to be viewed as embodying the attributes of the individual portrayed. Cassius Dio wrote that following the death of Caligula

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), better known by his nickname Caligula (), was the third Roman emperor, ruling from 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the popular Roman general Germanicu ...

the Senate demonetized his coinage and ordered that they be melted. Regardless of whether or not this actually occurred, it demonstrates the importance and meaning that was attached to the imagery on a coin. The philosopher Epictetus jokingly wrote: "Whose image does this sestertius carry? Trajan's? Give it to me. Nero's? Throw it away, it is unacceptable, it is rotten." Although the writer did not seriously expect people to get rid of their coins, this quotation demonstrates that the Romans attached a moral value to the images on their coins. Unlike the obverse, which during the Imperial period almost always featured a portrait, the reverse was far more varied in its depiction. During the late Republic there were often political messages to the imagery, especially during the periods of civil war. However, by the middle of the Empire, although there were types that made important statements, and some that were overtly political or propagandistic in nature, the majority of the types were stock images of personifications or deities. While some images can be related to the policy or actions of a particular emperor, many of the choices seem arbitrary and the personifications and deities were so prosaic that their names were often omitted, as they were readily recognizable by their appearance and attributes alone.

It can be argued that within this backdrop of mostly indistinguishable types, exceptions would be far more pronounced. Atypical reverses are usually seen during and after periods of war, at which time emperors make various claims of liberation, subjugation, and pacification. Some of these reverse images can clearly be classified as propaganda. An example struck by emperor Philip the Arab in 244 features a legend proclaiming the establishment of peace with Persia; in truth, Rome had been forced to pay large sums in tribute to the Persians.

Although it is difficult to make accurate generalizations about reverse imagery, as this was something that varied by emperor, some trends do exist. An example is reverse types of the military emperors during the second half of the third century, where virtually all of the types were the common and standard personifications and deities. A possible explanation for the lack of originality is that these emperors were attempting to present conservative images to establish their legitimacy, something that many of these emperors lacked. Although these emperors relied on traditional reverse types, their portraits often emphasized their authority through stern gazes, and even featured the bust of the emperor clad in armor.

Value and composition

Unlike most modern coins, Roman coins had (at least in the early centuries) significant intrinsic value. However, while the gold and silver issues contained precious metals, the value of a coin could be slightly higher than its precious metal content, so they were not, strictly speaking, equivalent tobullion

Bullion is non-ferrous metal that has been refined to a high standard of elemental purity. The term is ordinarily applied to bulk metal used in the production of coins and especially to precious metals such as gold and silver. It comes from t ...

. Also, over the course of time the purity and weight of the silver coins were reduced. Estimates of the value of the '' denarius'' range from 1.6 to 2.85 times its metal content, thought to equal the purchasing power of 10 modern British pound sterling

Sterling (abbreviation: stg; Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen. ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound ( sign: £) is the main unit of sterling, and t ...

at the beginning of the Roman Empire to around 18 pound sterling by its end (comparing bread, wine, and meat prices) and, over the same period, around one to three days' pay for a legionary

The Roman legionary (in Latin ''legionarius'', plural ''legionarii'') was a professional heavy infantryman of the Roman army after the Marian reforms. These soldiers would conquer and defend the territories of ancient Rome during the late Republi ...

.

The coinage system that existed in Egypt until the time of Diocletian's monetary reform was a closed system based upon the heavily debased tetradrachm. Although the value of these tetradrachms can be reckoned as being equivalent to that of the ''denarius'', their precious metal content was always much lower. Elsewhere also, not all coins that circulated contained precious metals, as the value of these coins was too great to be convenient for everyday purchases. A dichotomy existed between the coins with an intrinsic value and those with only a token value. This is reflected in the infrequent and inadequate production of bronze coinage during the Republic, where from the time of Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman general and statesman. He won the first large-scale civil war in Roman history and became the first man of the Republic to seize power through force.

Sulla had ...

till the time of Augustus no bronze coins were minted at all; even during the periods when bronze coins were produced, their workmanship was sometimes very crude and of low quality.

Debasement

The type of coins issued changed under the coinage reform of

The type of coins issued changed under the coinage reform of Diocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

, the heavily debased '' antoninianus'' (double ''denarius'') was replaced with a variety of new denominations, and a new range of imagery was introduced that attempted to convey different ideas. The new government set up by Diocletian was a Tetrarchy, or rule by four, with each emperor receiving a separate territory to rule.

The new imagery includes a large, stern portrait that is representative of the emperor. This image was not meant to show the actual portrait of a particular emperor, but was instead a character that embodied the power that the emperor possessed. The reverse type was equally universal, featuring the spirit (or genius) of the Romans. The introduction of a new type of government and a new system of coinage represents an attempt by Diocletian to return peace and security to Rome, after the previous century of constant warfare and uncertainty. Diocletian characterizes the emperor as an interchangeable authority figure by depicting him with a generalized image. He tries to emphasize unity amongst the Romans by featuring the spirit of Romans (Sutherland 254). The reverse types of coins of the late Empire emphasized general themes, and discontinued the more specific personifications depicted previously. The reverse types featured legends that proclaimed the glory of Rome, the glory of the Roman army

The Roman army (Latin: ) was the armed forces deployed by the Romans throughout the duration of Ancient Rome, from the Roman Kingdom (c. 500 BC) to the Roman Republic (500–31 BC) and the Roman Empire (31 BC–395 AD), and its medieval continu ...

, victory against the "barbarians", the restoration of happy times, and the greatness of the emperor.

These general types persisted even after the adoption of Christianity as the state religion of the Roman Empire. Muted Christian imagery, such as standards that featured Christogram

A Christogram ( la, Monogramma Christi) is a monogram or combination of letters that forms an abbreviation for the name of Jesus Christ, traditionally used as a Christian symbolism, religious symbol within the Christian Church.

One of the oldes ...

s (the Chi Rho

The Chi Rho (☧, English pronunciation ; also known as ''chrismon'') is one of the earliest forms of Christogram, formed by superimposing the first two (capital) letters— chi and rho (ΧΡ)—of the Greek word ( Christos) in such a way t ...

monogram for Jesus Christ's name in Greek) were introduced, but with a few rare exceptions, there were no explicitly Christian themes. From the time of Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

until the "end" of the Roman Empire, coins featured almost indistinguishable idealized portraits and general proclamations of greatness.

Although the ''denarius'' remained the backbone of the Roman economy from its introduction a few years before 211 BC until it ceased to be normally minted in the middle of the third century, the purity and weight of the coin slowly, but inexorably, decreased. The problem of debasement in the Roman economy appears to be pervasive, although the severity of the debasement often paralleled the strength or weakness of the Empire. While it is not clear why debasement became such a common occurrence for the Romans, it's believed that it was caused by several factors, including a lack of precious metals and inadequacies in state finances. When introduced, the ''denarius'' contained nearly pure silver at a theoretical weight of approximately 4.5 grams, but from the time of Nero onwards the tendency was nearly always for its purity to be decreased.

The theoretical standard, although not usually met in practice, remained fairly stable throughout the Republic, with the notable exception of times of war. The large number of coins required to raise an army and pay for supplies often necessitated the debasement of the coinage. An example of this is the ''denarii'' that were struck by Mark Antony to pay his army during his battles against Octavian. These coins, slightly smaller in diameter than a normal ''denarius'', were made of noticeably debased silver. The obverse features a galley and the name Antony, while the reverse features the name of the particular legion that each issue was intended for (hoard evidence shows that these coins remained in circulation over 200 years after they were minted, due to their lower silver content). The coinage of the Julio-Claudians remained stable at 4 grams of silver, until the debasement of Nero in 64, when the silver content was reduced to 3.8 grams, perhaps due to the cost of rebuilding the city after fire consumed a considerable portion of Rome.

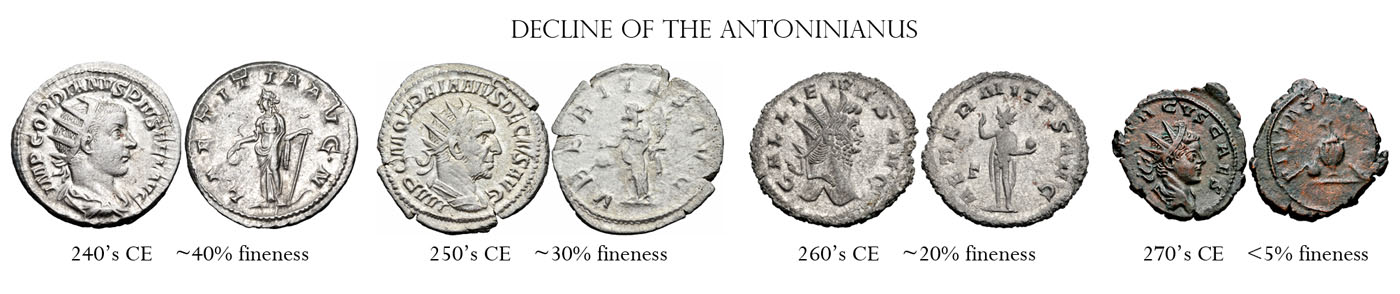

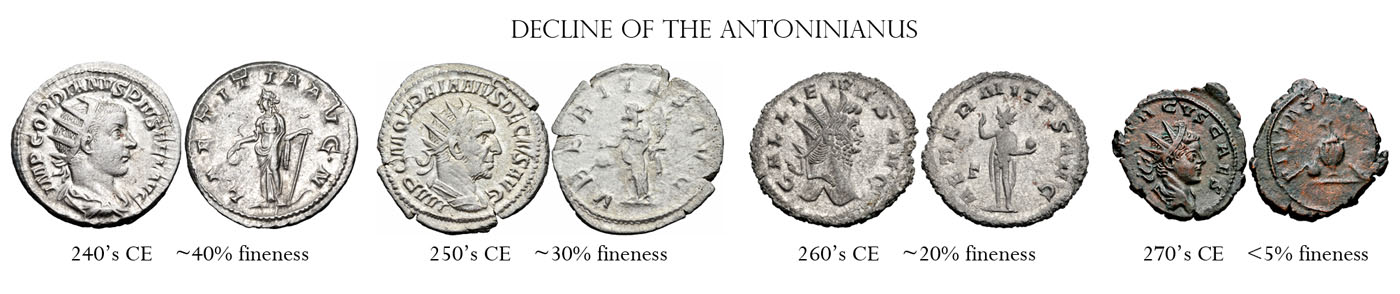

The ''denarius'' continued to decline slowly in purity, with a notable reduction instituted by Septimius Severus. This was followed by the introduction of a double ''denarius'' piece, differentiated from the ''denarius'' by the radiate crown worn by the emperor. The coin is commonly called the '' antoninianus'' by numismatists after the emperor Caracalla, who introduced the coin in early 215. Although nominally valued at two ''denarii'', the ''antoninianus'' never contained more than 1.6 times the amount of silver of the ''denarius''. The profit of minting a coin valued at two ''denarii'', but weighing only about one and a half times as much is obvious; the reaction to these coins by the public is unknown. As the number of ''antoniniani'' minted increased, the number of ''denarii'' minted decreased, until the ''denarius'' ceased to be minted in significant quantities by the middle of the third century. Again, coinage saw its greatest debasement during times of war and uncertainty. The second half of the third century was rife with this war and uncertainty, and the silver content of the ''antonianus'' fell to only 2%, losing almost any appearance of being silver. During this time the '' aureus'' remained slightly more stable, before it too became smaller and more base (lower gold content and higher base metal content) before Diocletian's reform.

The decline in the silver content to the point where coins contained virtually no silver at all was countered by the monetary reform of Aurelian

Aurelian ( la, Lucius Domitius Aurelianus; 9 September 214 October 275) was a Roman emperor, who reigned during the Crisis of the Third Century, from 270 to 275. As emperor, he won an unprecedented series of military victories which reunited t ...

in 274. The standard for silver in the ''antonianus'' was set at twenty parts copper to one part silver, and the coins were noticeably marked as containing that amount (XXI in Latin or KA in Greek). Despite the reform of Aurelian, silver content continued to decline, until the monetary reform of Diocletian. In addition to establishing the Tetrarchy, Diocletian devised the following system of denominations: an ''aureus'' struck at the standard of 60 to the pound, a new silver coin struck at the old Neronian standard known as the '' argenteus'', and a new large bronze coin that contained two percent silver.

Diocletian issued an Edict on Maximum Prices in 301, which attempted to establish the legal maximum prices that could be charged for goods and services. The attempt to establish maximum prices was an exercise in futility as maximum prices were impossible to enforce. The Edict was reckoned in terms of ''denarii'', although no such coin had been struck for over 50 years (it is believed that the bronze ''follis'' was valued at denarii). Like earlier reforms, this too eroded and was replaced by an uncertain coinage consisting mostly of gold and bronze. The exact relationship and denomination of the bronze issues of a variety of sizes is not known, and is believed to have fluctuated heavily on the market.

The exact reason that Roman coinage sustained continuous debasement is not known, but the most common theories involve inflation, trade with India (which drained silver from the Mediterranean world) and inadequacies in state finances. It is clear from papyri that the pay of the Roman soldier increased from 900 ''sestertii'' a year under Augustus to 2,000 ''sestertii'' a year under Septimius Severus, while the price of grain more than tripled, indicating a fall in real wages and moderate inflation during this time.

Equivalences

The first rows show the values of each boldface coin in the first column in relation to the coins in the following columns:See also

*Roman provincial currency

Roman provincial currency was coinage minted within the Roman Empire by local civic rather than imperial authorities. These coins were often continuations of the original currencies that existed prior to the arrival of the Romans. Because so many ...

* Roman finance

* List of historical currencies

* Byzantine coinage

References

Footnotes

Bibliography

* * Cohen, Henry, ''Description historiques des monnaies frappées sous l'Empire romain'', Paris, 1882, 8 vols. There existonline version of this Cohen's catalogue

* Greene, Kevin. ''Archaeology of the Roman Economy''. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1986. * Howgego, Christopher. ''Ancient History from Coins''. London: Routledge, 1995. * Jones, A. H. M. ''The Roman Economy: Studies in Ancient Economic and Administrative History''. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1974. * Melville Jones, John R., 'A Dictionary of Ancient Roman Coins', London, Spink 2003. * * * Salmon, E. Togo. ''Roman Coins and Public Life under the Empire''. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan Press, 1999. * Suarez, Rasiel. ''The Encyclopedia of Roman Imperial Coins''. Dirty Old Books, 2005. * Sutherland, C. H. V. ''Roman Coins''. New York: G. P. (Also published by Barrie and Jenkins in London in 1974 with ) * Van Meter, David. ''The Handbook of Roman Imperial Coins''. Laurion Press, 1990. * Vecchi, Italo. ''Italian Cast Coinage. A descriptive catalogue of the cast coinage of Rome and Italy.'' London Ancient Coins, London 2013. Hard bound in quarto format, 84 pages, 92 plates. * Modena Altieri, Ascanio. ''Vis et Mos. A compendium of symbologies and allegorical personifications in the imperial coinage from Augustus to Diocletian''. Florence, Porto Seguro Editore, 2022.

External links

A Collection of Flavian coins

Currency Debasement and Social Collapse

Ludwig von Mises {{Authority control Numismatics Economic history of Italy Currency