Anaximander World Map-en on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anaximander (; grc-gre, Ἀναξίμανδρος ''Anaximandros''; ) was a

Anaximander's bold use of non-

Anaximander's bold use of non- At the origin, after the separation of hot and cold, a ball of flame appeared that surrounded Earth like bark on a tree. This ball broke apart to form the rest of the Universe. It resembled a system of hollow concentric wheels, filled with fire, with the rims pierced by holes like those of a flute. Consequently, the Sun was the fire that one could see through a hole the same size as the Earth on the farthest wheel, and an eclipse corresponded with the

At the origin, after the separation of hot and cold, a ball of flame appeared that surrounded Earth like bark on a tree. This ball broke apart to form the rest of the Universe. It resembled a system of hollow concentric wheels, filled with fire, with the rims pierced by holes like those of a flute. Consequently, the Sun was the fire that one could see through a hole the same size as the Earth on the farthest wheel, and an eclipse corresponded with the

Both

Both

E. W. Webster

* Aristotle: ''

H. H. Joachim

* Aristotle: ''

J. L. Stocks

* (III, 5, 204 b 33–34) *

LacusCurtius

* (I, 50, 112) * Cicero: ''On the Nature of the Gods'' (I, 10, 25) * *

E. P. Coleridge

*

E.H. Gifford

* Heidel, W.A. ''Anaximander's Book'': PAAAS, vol. 56, n.7, 1921, pp. 239–288. *

Perseus project

* Hippolytus (?): ''Refutation of All Heresies'' (I, 5) Translated b

Roberts and Donaldson

*

Perseus project

*

H. L. Jones

*

''Suda On Line''

((Grk icon))

*

Life and Work - Fragments and Testimonies by Giannis Stamatellos {{Authority control 6th-century BC Greek people 6th-century BC philosophers 610s BC births 540s BC deaths Ancient Greek astronomers Ancient Greek cartographers Ancient Greek metaphysicians Ancient Greek physicists Ancient Greeks from the Achaemenid Empire Ancient Milesians Natural philosophers Philosophers of ancient Ionia Presocratic philosophers 6th-century BC geographers

pre-Socratic

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as early Greek philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of thes ...

Greek philosopher

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empire ...

who lived in Miletus

Miletus (; gr, Μῑ́λητος, Mī́lētos; Hittite transcription ''Millawanda'' or ''Milawata'' (exonyms); la, Mīlētus; tr, Milet) was an ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia, near the mouth of the Maeander River in a ...

,"Anaximander" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia

''Chambers's Encyclopaedia'' was founded in 1859Chambers, W. & R"Concluding Notice"in ''Chambers's Encyclopaedia''. London: W. & R. Chambers, 1868, Vol. 10, pp. v–viii. by William Chambers (publisher), William and Robert Chambers (publisher ...

''. London: George Newnes

Sir George Newnes, 1st Baronet (13 March 1851 – 9 June 1910) was a British publisher and editor and a founding figure in popular journalism. Newnes also served as a Liberal Party Member of Parliament for two decades. His company, George Newnes ...

, 1961, Vol. 1, p. 403. a city of Ionia

Ionia () was an ancient region on the western coast of Anatolia, to the south of present-day Izmir. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionian ...

(in modern-day Turkey). He belonged to the Milesian school

The Ionian school of Pre-Socratic philosophy was centred in Miletus, Ionia in the 6th century BC. Miletus and its environment was a thriving mercantile melting pot of current ideas of the time. The Ionian School included such thinkers as Thales, ...

and learned the teachings of his master Thales

Thales of Miletus ( ; grc-gre, Θαλῆς; ) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. He was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regarded him ...

. He succeeded Thales and became the second master of that school where he counted Anaximenes and, arguably, Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samos, Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionians, Ionian Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher and the eponymou ...

amongst his pupils.

Little of his life and work is known today. According to available historical documents, he is the first philosopher known to have written down his studies, although only one fragment of his work remains. Fragmentary testimonies found in documents after his death provide a portrait of the man.

Anaximander was an early proponent of science

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence for ...

and tried to observe and explain different aspects of the universe, with a particular interest in its origins, claiming that nature is ruled by laws, just like human societies, and anything that disturbs the balance of nature does not last long. Like many thinkers of his time, Anaximander's philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

included contributions to many disciplines. In astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

, he attempted to describe the mechanics of celestial bodies in relation to the Earth. In physics, his postulation that the indefinite (or apeiron

''Apeiron'' (; ) is a Greek word meaning "(that which is) unlimited," "boundless", "infinite", or "indefinite" from ''a-'', "without" and ''peirar'', "end, limit", "boundary", the Ionic Greek form of ''peras'', "end, limit, boundary".

Origin ...

) was the source of all things led Greek philosophy to a new level of conceptual abstraction

Abstraction in its main sense is a conceptual process wherein general rules and concepts are derived from the usage and classification of specific examples, literal ("real" or "concrete") signifiers, first principles, or other methods.

"An abstr ...

. His knowledge of geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

allowed him to introduce the gnomon

A gnomon (; ) is the part of a sundial that casts a shadow. The term is used for a variety of purposes in mathematics and other fields.

History

A painted stick dating from 2300 BC that was excavated at the astronomical site of Taosi is the ol ...

in Greece. He created a map of the world that contributed greatly to the advancement of geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and ...

. He was also involved in the politics

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studies ...

of Miletus and was sent as a leader to one of its colonies.

Biography

Anaximander, son of Praxiades, was born in the third year of the 42ndOlympiad

An olympiad ( el, Ὀλυμπιάς, ''Olympiás'') is a period of four years, particularly those associated with the ancient and modern Olympic Games.

Although the ancient Olympics were established during Greece's Archaic Era, it was not until ...

(610 BC). Hippolytus (?), ''Refutation of All Heresies

The ''Refutation of All Heresies'' ( grc-gre, Φιλοσοφούμενα ή κατὰ πασῶν αἱρέσεων ἔλεγχος; la, Refutatio Omnium Haeresium), also called the ''Elenchus'' or ''Philosophumena'', is a compendious Christian po ...

'' (I, 5) According to Apollodorus of Athens

Apollodorus of Athens ( el, Ἀπολλόδωρος ὁ Ἀθηναῖος, ''Apollodoros ho Athenaios''; c. 180 BC – after 120 BC) son of Asclepiades, was a Greek scholar, historian, and grammarian. He was a pupil of Diogenes of Babylon, Pan ...

, Greek grammarian of the 2nd century BC, he was sixty-four years old during the second year of the 58th Olympiad (547–546 BC), and died shortly afterwards.

Establishing a timeline of his work is now impossible, since no document provides chronological references. Themistius

Themistius ( grc-gre, Θεμίστιος ; 317 – c. 388 AD), nicknamed Euphrades, (eloquent), was a statesman, rhetorician, and philosopher. He flourished in the reigns of Constantius II, Julian, Jovian, Valens, Gratian, and Theodosius I; ...

, a 4th-century Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate parti ...

ian, mentions that he was the "first of the known Greeks to publish a written document on nature." Therefore, his texts would be amongst the earliest written in prose

Prose is a form of written or spoken language that follows the natural flow of speech, uses a language's ordinary grammatical structures, or follows the conventions of formal academic writing. It differs from most traditional poetry, where the f ...

, at least in the Western world. By the time of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, his philosophy was almost forgotten, and Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

, his successor Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routledge ...

and a few doxographers provide us with the little information that remains. However, we know from Aristotle that Thales, also from Miletus, precedes Anaximander. It is debatable whether Thales actually was the teacher of Anaximander, but there is no doubt that Anaximander was influenced by Thales' theory that everything is derived from water. One thing that is not debatable is that even the ancient Greeks considered Anaximander to be from the Monist

Monism attributes oneness or singleness (Greek: μόνος) to a concept e.g., existence. Various kinds of monism can be distinguished:

* Priority monism states that all existing things go back to a source that is distinct from them; e.g., i ...

school which began in Miletus, with Thales followed by Anaximander and which ended with Anaximenes. 3rd-century Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

rhetorician Aelian depicts Anaximander as leader of the Milesian colony to Apollonia on the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

coast, and hence some have inferred that he was a prominent citizen. Indeed, ''Various History'' (III, 17) explains that philosophers sometimes also dealt with political matters. It is very likely that leaders of Miletus sent him there as a legislator to create a constitution or simply to maintain the colony's allegiance.

Anaximander lived the final few years of his life as a subject of the Persian Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was the largest empire the world had ...

.

Theories

Anaximander's theories were influenced by the Greek mythical tradition, and by some ideas ofThales

Thales of Miletus ( ; grc-gre, Θαλῆς; ) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. He was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regarded him ...

– the father of Western philosophy

Western philosophy encompasses the philosophical thought and work of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the pre-Socratics. The word ' ...

– as well as by observations made by older civilizations in the Near East, especially Babylon. All these were developed rationally. In his desire to find some universal principle, he assumed, like traditional religion, the existence of a cosmic order; and his ideas on this used the old language of myths which ascribed divine control to various spheres of reality. This was a common practice for the Greek philosophers in a society which saw gods everywhere, and therefore could fit their ideas into a tolerably elastic system.

Some scholars see a gap between the existing mythical and the new rational

Rationality is the quality of being guided by or based on reasons. In this regard, a person acts rationally if they have a good reason for what they do or a belief is rational if it is based on strong evidence. This quality can apply to an abi ...

way of thought which is the main characteristic of the archaic period (8th to 6th century BC) in the Greek city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

s. This has given rise to the phrase "Greek miracle". But if we follow carefully the course of Anaximander's ideas, we will notice that there was not such an abrupt break as initially appears. The basic elements of nature (water

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as a ...

, air

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing f ...

, fire

Fire is the rapid oxidation of a material (the fuel) in the exothermic chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction Product (chemistry), products.

At a certain point in the combustion reaction, called the ignition ...

, earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

) which the first Greek philosophers believed made up the universe in fact represent the primordial forces imagined in earlier ways of thinking. Their collision produced what the mythical tradition had called cosmic harmony. In the old cosmogonies – Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

(8th – 7th century BC) and Pherecydes (6th century BC) – Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label=Genitive case, genitive Aeolic Greek, Boeotian Aeolic and Doric Greek#Laconian, Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label=Genitive case, genitive el, Δίας, ''D� ...

establishes his order in the world by destroying the powers which were threatening this harmony (the Titans

In Greek mythology, the Titans ( grc, οἱ Τῑτᾶνες, ''hoi Tītânes'', , ''ho Tītân'') were the pre-Olympian gods. According to the ''Theogony'' of Hesiod, they were the twelve children of the primordial parents Uranus (Sky) and Ga ...

). Anaximander claimed that the cosmic order is not monarchic

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy) ...

but geometric, and that this causes the equilibrium of the earth, which is lying in the centre of the universe. This is the projection on nature of a new political order and a new space organized around a centre which is the static point of the system in the society as in nature. In this space there is ''isonomy'' (equal rights) and all the forces are symmetrical and transferable. The decisions are now taken by the assembly of ''demos

Demos may refer to:

Computing

* DEMOS, a Soviet Unix-like operating system

* DEMOS (ISP), the first internet service provider in the USSR

* Demos Commander, an Orthodox File Manager for Unix-like systems

* plural for Demo (computer programming)

...

'' in the ''agora

The agora (; grc, ἀγορά, romanized: ', meaning "market" in Modern Greek) was a central public space in ancient Greek city-states. It is the best representation of a city-state's response to accommodate the social and political order of t ...

'' which is lying in the middle of the city.

The same ''rational'' way of thought led him to introduce the abstract ''apeiron

''Apeiron'' (; ) is a Greek word meaning "(that which is) unlimited," "boundless", "infinite", or "indefinite" from ''a-'', "without" and ''peirar'', "end, limit", "boundary", the Ionic Greek form of ''peras'', "end, limit, boundary".

Origin ...

'' (indefinite, infinite, boundless, unlimited) as an origin of the universe, a concept that is probably influenced by the original Chaos

Chaos or CHAOS may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media Fictional elements

* Chaos (''Kinnikuman'')

* Chaos (''Sailor Moon'')

* Chaos (''Sesame Park'')

* Chaos (''Warhammer'')

* Chaos, in ''Fabula Nova Crystallis Final Fantasy''

* Cha ...

(gaping void, abyss, formless state) from which everything else appeared in the mythical Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

cosmogony

Cosmogony is any model concerning the origin of the cosmos or the universe.

Overview

Scientific theories

In astronomy, cosmogony refers to the study of the origin of particular astrophysical objects or systems, and is most commonly used i ...

. It also takes notice of the mutual changes between the four elements. Origin, then, must be something else unlimited in its source, that could create without experiencing decay, so that genesis would never stop.

Apeiron

The ''Refutation'' attributed toHippolytus of Rome

Hippolytus of Rome (, ; c. 170 – c. 235 AD) was one of the most important second-third century Christian theologians, whose provenance, identity and corpus remain elusive to scholars and historians. Suggested communities include Rome, Palestin ...

(I, 5), and the later 6th century Byzantine philosopher Simplicius of Cilicia

Simplicius of Cilicia (; el, Σιμπλίκιος ὁ Κίλιξ; c. 490 – c. 560 AD) was a disciple of Ammonius Hermiae and Damascius, and was one of the last of the Neoplatonists. He was among the pagan philosophers persecuted by Justinian i ...

, attribute to Anaximander the earliest use of the word ''apeiron'' ( "infinite" or "limitless") to designate the original principle. He was the first philosopher to employ, in a philosophical context, the term ''archē

''Arche'' (; grc, ἀρχή; sometimes also transcribed as ''arkhé'') is a Greek word with primary senses "beginning", "origin" or "source of action" (: from the beginning, οr : the original argument), and later "first principle" or "element". ...

'' (), which until then had meant beginning or origin.

"That Anaximander called this something by the name of is the natural interpretation of what Theophrastos says; the current statement that the term was introduced by him appears to be due to a misunderstanding."

And "Hippolytos, however, is not an independent authority, and the only question is what Theophrastos wrote."

For him, it became no longer a mere point in time, but a source that could perpetually give birth to whatever will be. The indefiniteness is spatial in early usages as in Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

(indefinite sea) and as in Xenophanes

Xenophanes of Colophon (; grc, Ξενοφάνης ὁ Κολοφώνιος ; c. 570 – c. 478 BC) was a Greek philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φ ...

(6th century BC) who said that the earth went down indefinitely (to ''apeiron'') i.e. beyond the imagination or concept of men.

Burnet (1930) in ''Early Greek Philosophy'' says:

"Nearly all we know of Anaximander’s system is derived in the last resort from Theophrastos, who certainly knew his book. He seems once at least to have quoted Anaximander's own words, and he criticised his style. Here are the remains of what he said of him in the First Book:

Burnet's quote from the "First Book" is his translation of Theophrastos' ''Physic Opinion'' fragment 2 as it appears in p. 476 of ''Historia Philosophiae Graecae'' (1898) by Ritter and Preller and section 16 of ''Doxographi Graeci'' (1879) by Diels. By ascribing the "Infinite" with a "material cause", Theophrastos is following the Aristotelian tradition of "nearly always discussing the facts from the point of view of his own system". Aristotle writes (''"Anaximander of Miletos, son of Praxiades, a fellow-citizen and associate of Thales, said that the material cause and first element of things was the Infinite, he being the first to introduce this name of the material cause. He says it is neither water nor any other of the so-called elements, but a substance different from them which is infinite" peiron, or "from which arise all the heavens and the worlds within them.—Phys, Op. fr. 2 (Dox. p. 476; R. P. 16)."

Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

'', I.III 3–4) that the Pre-Socratics

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as early Greek philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of thes ...

were searching for the element that constitutes all things. While each pre-Socratic philosopher gave a different answer as to the identity of this element (water

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as a ...

for Thales and air

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing f ...

for Anaximenes), Anaximander understood the beginning or first principle to be an endless, unlimited primordial mass (''apeiron''), subject to neither old age nor decay, that perpetually yielded fresh materials from which everything we perceive is derived. He proposed the theory of the ''apeiron'' in direct response to the earlier theory of his teacher, Thales, who had claimed that the primary substance was water. The notion of temporal infinity was familiar to the Greek mind from remote antiquity in the religious concept of immortality, and Anaximander's description was in terms appropriate to this conception. This ''archē'' is called "eternal and ageless". (Hippolytus (?), ''Refutation'', I,6,I;DK B2)"''Aristotle puts things in his own way regardless of historical considerations, and it is difficult to see that it is more of an anachronism to call the Boundless “ intermediate between the elements ” than to say that it is " distinct from the elements.” Indeed, if once we introduce the elements at all, the former description is the more adequate of the two. At any rate, if we refuse to understand these passages as referring to Anaximander, we shall have to say that Aristotle paid a great deal of attention to some one whose very name has been lost, and who not only agreed with some of Anaximander’s views, but also used some of his most characteristic expressions. We may add that in one or two places Aristotle certainly seems to identify the “ intermediate ” with the something “ distinct from ” the elements''."

"It is certain that he naximandercannot have said anything about elements, which no one thought of before Empedokles, and no one could think of before Parmenides. The question has only been mentioned because it has given rise to a lengthy controversy, and because it throws light on the historical value of Aristotle’s statements. From the point of view of his own system, these may be justified; but we shall have to remember in other cases that, when he seems to attribute an idea to some earlier thinker, we are not bound to take what he says in an historical sense."For Anaximander, the

principle

A principle is a proposition or value that is a guide for behavior or evaluation. In law, it is a Legal rule, rule that has to be or usually is to be followed. It can be desirably followed, or it can be an inevitable consequence of something, suc ...

of things, the constituent of all substances, is nothing determined and not an element such as water in Thales' view. Neither is it something halfway between air and water, or between air and fire, thicker than air and fire, or more subtle than water and earth. Anaximander argues that water cannot embrace all of the opposites found in nature — for example, water can only be wet, never dry — and therefore cannot be the one primary substance; nor could any of the other candidates. He postulated the ''apeiron'' as a substance that, although not directly perceptible to us, could explain the opposites he saw around him."If Thales had been right in saying that water was the fundamental reality, it would not be easy to see how anything else could ever have existed. One side of the opposition, the cold and moist, would have had its way unchecked, and the warm and dry would have been driven from the field long ago. We must, then, have something not itself one of the warring opposites, something more primitive, out of which they arise, and into which they once more pass away."Anaximander explains how the

four elements

Classical elements typically refer to earth, water, air, fire, and (later) aether which were proposed to explain the nature and complexity of all matter in terms of simpler substances. Ancient cultures in Greece, Tibet, and India had simi ...

of ancient physics (air

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing f ...

, earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

, water

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as a ...

and fire

Fire is the rapid oxidation of a material (the fuel) in the exothermic chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction Product (chemistry), products.

At a certain point in the combustion reaction, called the ignition ...

) are formed, and how Earth and terrestrial beings are formed through their interactions. Unlike other Pre-Socratics, he never defines this principle precisely, and it has generally been understood (e.g., by Aristotle and by Saint Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Af ...

) as a sort of primal chaos

Chaos or CHAOS may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media Fictional elements

* Chaos (''Kinnikuman'')

* Chaos (''Sailor Moon'')

* Chaos (''Sesame Park'')

* Chaos (''Warhammer'')

* Chaos, in ''Fabula Nova Crystallis Final Fantasy''

* Cha ...

. According to him, the Universe originates in the separation of opposites in the primordial matter. It embraces the opposites of hot and cold, wet and dry, and directs the movement of things; an entire host of shapes and differences then grow that are found in "all the worlds" (for he believed there were many)."Anaximander taught, then, that there was an eternal. The indestructible something out of which everything arises, and into which everything returns; a boundless stock from which the waste of existence is continually made good, “elements.”. That is only the natural development of the thought we have ascribed to Thales, and there can be no doubt that Anaximander at least formulated it distinctly. Indeed, we can still follow to some extent the reasoning which led him to do so. Thales had regarded water as the most likely thing to be that of which all others are forms; Anaximander appears to have asked how the primary substance could be one of these particular things. His argument seems to be preserved by Aristotle, who has the following passage in his discussion of the Infinite: ''"Further, there cannot be a single, simple body which is infinite, either, as some hold, one distinct from the elements, which they then derive from it, or without this qualification. For there are some who make this. (i.e. a body distinct from the elements). the infinite, and not air or water, in order that the other things may not be destroyed by their infinity. They are in opposition one to another. air is cold, water moist, and fire hot. and therefore, if any one of them were infinite, the rest would have ceased to be by this time. Accordingly they say that what is infinite is something other than the elements, and from it the elements arise.'—Aristotle Physics. F, 5 204 b 22 (Ritter and Preller (1898) Historia Philosophiae Graecae, section 16 b)."''Anaximander maintains that all dying things are returning to the element from which they came (''apeiron''). The one surviving fragment of Anaximander's writing deals with this matter. Simplicius transmitted it as a quotation, which describes the balanced and mutual changes of the elements:

Whence things have their origin,Simplicius mentions that Anaximander said all these "in poetic terms", meaning that he used the old mythical language. The goddess Justice (

Thence also their destruction happens,

According to necessity;

For they give to each other justice and recompense

For their injustice

In conformity with the ordinance of Time.

Dike

Dyke (UK) or dike (US) may refer to:

General uses

* Dyke (slang), a slang word meaning "lesbian"

* Dike (geology), a subvertical sheet-like intrusion of magma or sediment

* Dike (mythology), ''Dikē'', the Greek goddess of moral justice

* Dikes ...

) keeps the cosmic order. This concept of returning to the element of origin was often revisited afterwards, notably by Aristotle, and by the Greek tragedian

Tragedy (from the grc-gre, τραγῳδία, ''tragōidia'', ''tragōidia'') is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful events that befall a main character. Traditionally, the intention of tragedy ...

Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Εὐριπίδης, Eurīpídēs, ; ) was a tragedian

Tragedy (from the grc-gre, τραγῳδία, ''tragōidia'', ''tragōidia'') is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful e ...

: "what comes from earth must return to earth." Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

, in his ''Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks

''Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks'' (german: Philosophie im tragischen Zeitalter der Griechen) is an incomplete book by Friedrich Nietzsche. He had a clean copy made from his notes with the intention of publication. The notes were writ ...

'', stated that Anaximander viewed "... all coming-to-be as though it were an illegitimate emancipation from eternal being, a wrong for which destruction is the only penance." Physicist Max Born

Max Born (; 11 December 1882 – 5 January 1970) was a German physicist and mathematician who was instrumental in the development of quantum mechanics. He also made contributions to solid-state physics and optics and supervised the work of a n ...

, in commenting upon Werner Heisenberg

Werner Karl Heisenberg () (5 December 1901 – 1 February 1976) was a German theoretical physicist and one of the main pioneers of the theory of quantum mechanics. He published his work in 1925 in a breakthrough paper. In the subsequent series ...

's arriving at the idea that the elementary particles of quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistry, ...

are to be seen as different manifestations, different quantum states, of one and the same “primordial substance,”' proposed that this primordial substance be called ''apeiron''.

Cosmology

mythological

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narrat ...

explanatory hypotheses considerably distinguishes him from previous cosmology writers such as Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

. It confirms that pre-Socratic philosophers were making an early effort to demystify physical processes. His major contribution to history was writing the oldest prose document about the Universe and the origins of life; for this he is often called the "Father of Cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount (lexicographer), Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in ...

" and founder of astronomy. However, pseudo-Plutarch Pseudo-Plutarch is the conventional name given to the actual, but unknown, authors of a number of pseudepigrapha (falsely attributed works) attributed to Plutarch but now known to have not been written by him.

Some of these works were included in s ...

states that he still viewed celestial bodies as deities.

Anaximander was the first to conceive a mechanical model of the world. In his model, the Earth floats very still in the centre of the infinite, not supported by anything. It remains "in the same place because of its indifference", a point of view that Aristotle considered ingenious, but false, in ''On the Heavens

''On the Heavens'' (Greek: ''Περὶ οὐρανοῦ''; Latin: ''De Caelo'' or ''De Caelo et Mundo'') is Aristotle's chief cosmological treatise: written in 350 BC, it contains his astronomical theory and his ideas on the concrete workings o ...

''. Its curious shape is that of a cylinder with a height one-third of its diameter. The flat top forms the inhabited world, which is surrounded by a circular oceanic mass.

Anaximander's realization that the Earth floats free without falling and does not need to be resting on something has been indicated by many as the first cosmological revolution and the starting point of scientific thinking. Karl Popper

Sir Karl Raimund Popper (28 July 1902 – 17 September 1994) was an Austrian-British philosopher, academic and social commentator. One of the 20th century's most influential philosophers of science, Popper is known for his rejection of the cl ...

calls this idea "one of the boldest, most revolutionary, and most portentous ideas in the whole history of human thinking." Such a model allowed the concept that celestial bodies could pass under the Earth, opening the way to Greek astronomy.

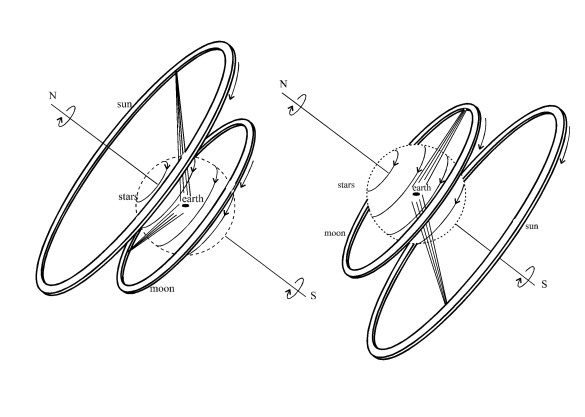

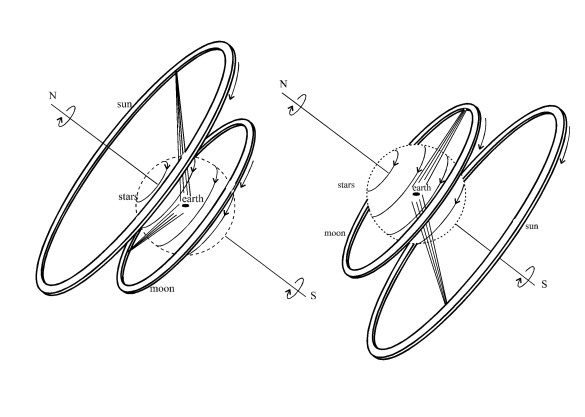

At the origin, after the separation of hot and cold, a ball of flame appeared that surrounded Earth like bark on a tree. This ball broke apart to form the rest of the Universe. It resembled a system of hollow concentric wheels, filled with fire, with the rims pierced by holes like those of a flute. Consequently, the Sun was the fire that one could see through a hole the same size as the Earth on the farthest wheel, and an eclipse corresponded with the

At the origin, after the separation of hot and cold, a ball of flame appeared that surrounded Earth like bark on a tree. This ball broke apart to form the rest of the Universe. It resembled a system of hollow concentric wheels, filled with fire, with the rims pierced by holes like those of a flute. Consequently, the Sun was the fire that one could see through a hole the same size as the Earth on the farthest wheel, and an eclipse corresponded with the occlusion

Occlusion may refer to:

Health and fitness

* Occlusion (dentistry), the manner in which the upper and lower teeth come together when the mouth is closed

* Occlusion miliaria, a skin condition

* Occlusive dressing, an air- and water-tight trauma ...

of that hole. The diameter of the solar wheel was twenty-seven times that of the Earth (or twenty-eight, depending on the sources) and the lunar wheel, whose fire was less intense, eighteen (or nineteen) times. Its hole could change shape, thus explaining lunar phase

Concerning the lunar month of ~29.53 days as viewed from Earth, the lunar phase or Moon phase is the shape of the Moon's directly sunlit portion, which can be expressed quantitatively using areas or angles, or described qualitatively using the t ...

s. The stars and the planets, located closer, followed the same model.

Anaximander was the first astronomer to consider the Sun as a huge mass, and consequently, to realize how far from Earth it might be, and the first to present a system where the celestial bodies turned at different distances. Furthermore, according to Diogenes Laertius (II, 2), he built a celestial sphere

In astronomy and navigation, the celestial sphere is an abstract sphere that has an arbitrarily large radius and is concentric to Earth. All objects in the sky can be conceived as being projected upon the inner surface of the celestial sphere, ...

. This invention undoubtedly made him the first to realize the obliquity

In astronomy, axial tilt, also known as obliquity, is the angle between an object's rotational axis and its orbital axis, which is the line perpendicular to its orbital plane; equivalently, it is the angle between its equatorial plane and orbi ...

of the Zodiac

The zodiac is a belt-shaped region of the sky that extends approximately 8° north or south (as measured in celestial latitude) of the ecliptic, the Sun path, apparent path of the Sun across the celestial sphere over the course of the year. ...

as the Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

reports in '' Natural History'' (II, 8). It is a little early to use the term ecliptic

The ecliptic or ecliptic plane is the orbital plane of the Earth around the Sun. From the perspective of an observer on Earth, the Sun's movement around the celestial sphere over the course of a year traces out a path along the ecliptic again ...

, but his knowledge and work on astronomy confirm that he must have observed the inclination of the celestial sphere in relation to the plane of the Earth to explain the seasons. The doxographer Doxography ( el, δόξα – "an opinion", "a point of view" + – "to write", "to describe") is a term used especially for the works of classical historians, describing the points of view of past philosophers and scientists. The term w ...

and theologian Aetius attributes to Pythagoras the exact measurement of the obliquity.

Multiple worlds

According to Simplicius, Anaximander already speculated on the plurality of worlds, similar toatomists

Atomism (from Greek , ''atomon'', i.e. "uncuttable, indivisible") is a natural philosophy proposing that the physical universe is composed of fundamental indivisible components known as atoms.

References to the concept of atomism and its atoms a ...

Leucippus

Leucippus (; el, Λεύκιππος, ''Leúkippos''; fl. 5th century BCE) is a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher who has been credited as the first philosopher to develop a theory of atomism.

Leucippus' reputation, even in antiquity, was obscured ...

and Democritus

Democritus (; el, Δημόκριτος, ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. No ...

, and later philosopher Epicurus

Epicurus (; grc-gre, Ἐπίκουρος ; 341–270 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher and sage who founded Epicureanism, a highly influential school of philosophy. He was born on the Greek island of Samos to Athenian parents. Influenced ...

. These thinkers supposed that worlds appeared and disappeared for a while, and that some were born when others perished. They claimed that this movement was eternal, "for without movement, there can be no generation, no destruction".

In addition to Simplicius, Hippolytus reports Anaximander's claim that from the infinite comes the principle of beings, which themselves come from the heavens and the worlds (several doxographers use the plural when this philosopher is referring to the worlds within, which are often infinite in quantity). Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

writes that he attributes different gods to the countless worlds.

This theory places Anaximander close to the Atomists and the Epicureans

Epicureanism is a system of philosophy founded around 307 BC based upon the teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus. Epicureanism was originally a challenge to Platonism. Later its main opponent became Stoicism.

Few writings by ...

who, more than a century later, also claimed that an infinity of worlds appeared and disappeared. In the timeline of the Greek history of thought, some thinkers conceptualized a single world (Plato, Aristotle, Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras (; grc-gre, Ἀναξαγόρας, ''Anaxagóras'', "lord of the assembly"; 500 – 428 BC) was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae at a time when Asia Minor was under the control of the Persian Empire, ...

and Archelaus), while others instead speculated on the existence of a series of worlds, continuous or non-continuous ( Anaximenes, Heraclitus

Heraclitus of Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἡράκλειτος , "Glory of Hera"; ) was an ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from the city of Ephesus, which was then part of the Persian Empire.

Little is known of Heraclitus's life. He wrote ...

, Empedocles

Empedocles (; grc-gre, Ἐμπεδοκλῆς; , 444–443 BC) was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for originating the cosmogonic theory of the fo ...

and Diogenes

Diogenes ( ; grc, Διογένης, Diogénēs ), also known as Diogenes the Cynic (, ) or Diogenes of Sinope, was a Greek philosopher and one of the founders of Cynicism (philosophy). He was born in Sinope, an Ionian colony on the Black Sea ...

).

Meteorological phenomena

Anaximander attributed some phenomena, such as thunder and lightning, to the intervention of elements, rather than to divine causes. In his system, thunder results from the shock of clouds hitting each other; the loudness of the sound is proportionate with that of the shock. Thunder without lightning is the result of the wind being too weak to emit any flame, but strong enough to produce a sound. A flash of lightning without thunder is a jolt of the air that disperses and falls, allowing a less active fire to break free. Thunderbolts are the result of a thicker and more violent air flow. He saw the sea as a remnant of the mass of humidity that once surrounded Earth. A part of that mass evaporated under the sun's action, thus causing the winds and even the rotation of the celestial bodies, which he believed were attracted to places where water is more abundant. He explained rain as a product of the humidity pumped up from Earth by the sun. For him, the Earth was slowly drying up and water only remained in the deepest regions, which someday would go dry as well. According to Aristotle's ''Meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did not ...

'' (II, 3), Democritus also shared this opinion.

Origin of humankind

Anaximander speculated about the beginnings andorigin

Origin(s) or The Origin may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Comics and manga

* Origin (comics), ''Origin'' (comics), a Wolverine comic book mini-series published by Marvel Comics in 2002

* The Origin (Buffy comic), ''The Origin'' (Bu ...

of animal life, and that humans came from other animals in waters. According to his evolutionary theory

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

, animals sprang out of the sea long ago, born trapped in a spiny bark, but as they got older, the bark would dry up and animals would be able to break it. As the early humidity evaporated, dry land emerged and, in time, humankind had to adapt. The 3rd century Roman writer Censorinus

Censorinus was a Roman grammarian and miscellaneous writer from the 3rd century AD.

Biography

He was the author of a lost work ''De Accentibus'' and of an extant treatise ''De Die Natali'', written in 238, and dedicated to his patron Quintus ...

reports:

Anaximander put forward the idea that humans had to spend part of this transition inside the mouths of big fish to protect themselves from the Earth's climate until they could come out in open air and lose their scales. He thought that, considering humans' extended infancy, we could not have survived in the primeval world in the same manner we do presently.

Other accomplishments

Cartography

Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

and Agathemerus

Agathemerus (Greek: ) was a Greek geographer who during the Roman Greece period published a small two-part geographical work titled ''A Sketch of Geography in Epitome'' (), addressed to his pupil Philon. The son of Orthon, Agathemerus is specula ...

(later Greek geographers) claim that, according to the geographer Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; grc-gre, Ἐρατοσθένης ; – ) was a Greek polymath: a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of Alexandria ...

, Anaximander was the first to publish a map of the world. The map probably inspired the Greek historian Hecataeus of Miletus

Hecataeus of Miletus (; el, Ἑκαταῖος ὁ Μιλήσιος; c. 550 BC – c. 476 BC), son of Hegesander, was an early Greek historian and geographer.

Biography

Hailing from a very wealthy family, he lived in Miletus, then under Per ...

to draw a more accurate version. Strabo viewed both as the first geographers after Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

.

Maps were produced in ancient times, also notably in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, Lydia

Lydia (Lydian language, Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the mod ...

, the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

, and Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

. Only some small examples survived until today. The unique example of a world map comes from late Babylonian tablet BM 92687 later than 9th century BC but is based probably on a much older map. These maps indicated directions, roads, towns, borders, and geological features. Anaximander's innovation was to represent the entire inhabited land known to the ancient Greeks.

Such an accomplishment is more significant than it at first appears. Anaximander most likely drew this map for three reasons. First, it could be used to improve navigation and trade between Miletus

Miletus (; gr, Μῑ́λητος, Mī́lētos; Hittite transcription ''Millawanda'' or ''Milawata'' (exonyms); la, Mīlētus; tr, Milet) was an ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia, near the mouth of the Maeander River in a ...

's colonies and other colonies around the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea. Second, Thales

Thales of Miletus ( ; grc-gre, Θαλῆς; ) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. He was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regarded him ...

would probably have found it easier to convince the Ionian city-states

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

to join in a federation in order to push the Median

In statistics and probability theory, the median is the value separating the higher half from the lower half of a data sample, a population, or a probability distribution. For a data set, it may be thought of as "the middle" value. The basic fe ...

threat away if he possessed such a tool. Finally, the philosophical idea of a global representation of the world simply for the sake of knowledge was reason enough to design one.

Surely aware of the sea's convexity, he may have designed his map on a slightly rounded metal surface. The centre or “navel” of the world ( ''omphalós gẽs'') could have been Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), in ancient times was a sacred precinct that served as the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient classical world. The oracle ...

, but is more likely in Anaximander's time to have been located near Miletus. The Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek language, Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish language, Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It ...

was near the map's centre and enclosed by three continents, themselves located in the middle of the ocean and isolated like islands by sea and rivers. Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

was bordered on the south by the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

and was separated from Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

by the Black Sea, the Lake Maeotis

The Sea of Azov ( Crimean Tatar: ''Azaq deñizi''; russian: Азовское море, Azovskoye more; uk, Азовське море, Azovs'ke more) is a sea in Eastern Europe connected to the Black Sea by the narrow (about ) Strait of Kerch, ...

, and, further east, either by the Phasis River (now called the Rioni

The Rioni ( ka, რიონი, ; , ) is the main river of western Georgia. It originates in the Caucasus Mountains, in the region of Racha and flows west to the Black Sea, entering it north of the city of Poti (near ancient Phasis). The city ...

in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

) or the Tanais

Tanais ( el, Τάναϊς ''Tánaïs''; russian: Танаис) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek city in the Don River (Russia), Don river delta, called the Maeotian Swamp, Maeotian marshes in classical antiquity. It was a bishopric as Tana ...

. The Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

flowed south into the ocean, separating Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

(which was the name for the part of the then-known Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

n continent) from Asia.

Gnomon

The ''Suda

The ''Suda'' or ''Souda'' (; grc-x-medieval, Σοῦδα, Soûda; la, Suidae Lexicon) is a large 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Soudas (Σούδας) or Souidas ...

'' relates that Anaximander explained some basic notions of geometry. It also mentions his interest in the measurement of time and associates him with the introduction in Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

of the gnomon. In Lacedaemon

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

, he participated in the construction, or at least in the adjustment, of sundial

A sundial is a horological device that tells the time of day (referred to as civil time in modern usage) when direct sunlight shines by the apparent position of the Sun in the sky. In the narrowest sense of the word, it consists of a flat ...

s to indicate solstice

A solstice is an event that occurs when the Sun appears to reach its most northerly or southerly excursion relative to the celestial equator on the celestial sphere. Two solstices occur annually, around June 21 and December 21. In many countr ...

s and equinox

A solar equinox is a moment in time when the Sun crosses the Earth's equator, which is to say, appears directly above the equator, rather than north or south of the equator. On the day of the equinox, the Sun appears to rise "due east" and se ...

es. Indeed, a gnomon

A gnomon (; ) is the part of a sundial that casts a shadow. The term is used for a variety of purposes in mathematics and other fields.

History

A painted stick dating from 2300 BC that was excavated at the astronomical site of Taosi is the ol ...

required adjustments from a place to another because of the difference in latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north pol ...

.

In his time, the gnomon was simply a vertical pillar or rod mounted on a horizontal plane. The position of its shadow on the plane indicated the time of day. As it moves through its apparent course, the Sun draws a curve with the tip of the projected shadow, which is shortest at noon, when pointing due south. The variation in the tip's position at noon indicates the solar time and the seasons; the shadow is longest on the winter solstice and shortest on the summer solstice.

The invention of the gnomon itself cannot be attributed to Anaximander because its use, as well as the division of days into twelve parts, came from the Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c. ...

ns. It is they, according to Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

' Histories (II, 109), who gave the Greeks the art of time measurement. It is likely that he was not the first to determine the solstices, because no calculation is necessary. On the other hand, equinoxes do not correspond to the middle point between the positions during solstices, as the Babylonians thought. As the ''Suda'' seems to suggest, it is very likely that with his knowledge of geometry, he became the first Greek to determine accurately the equinoxes.

Prediction of an earthquake

In his philosophical work '' De Divinatione'' (I, 50, 112), Cicero states that Anaximander convinced the inhabitants ofLacedaemon

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

to abandon their city and spend the night in the country with their weapons because an earthquake was near. The city collapsed when the top of the Taygetus

The Taygetus, Taugetus, Taygetos or Taÿgetus ( el, Ταΰγετος, Taygetos) is a mountain range on the Peloponnese peninsula in Southern Greece. The highest mountain of the range is Mount Taygetus, also known as "Profitis Ilias", or "Prophet ...

split like the stern of a ship. Pliny the Elder also mentions this anecdote (II, 81), suggesting that it came from an "admirable inspiration", as opposed to Cicero, who did not associate the prediction with divination.

Interpretations

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, ...

in the ''History of Western Philosophy

Western philosophy encompasses the philosophical thought and work of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the pre-Socratics. The word '' ...

'' interprets Anaximander's theories as an assertion of the necessity of an appropriate balance between earth, fire, and water, all of which may be independently seeking to aggrandize their proportions relative to the others. Anaximander seems to express his belief that a natural order ensures balance among these elements, that where there was fire, ashes (earth) now exist. His Greek peers echoed this sentiment with their belief in natural boundaries beyond which not even the gods could operate.

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

, in ''Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks

''Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks'' (german: Philosophie im tragischen Zeitalter der Griechen) is an incomplete book by Friedrich Nietzsche. He had a clean copy made from his notes with the intention of publication. The notes were writ ...

'', claimed that Anaximander was a pessimist who asserted that the primal being of the world was a state of indefiniteness. In accordance with this, anything definite has to eventually pass back into indefiniteness. In other words, Anaximander viewed "...all coming-to-be as though it were an illegitimate emancipation from eternal being, a wrong for which destruction is the only penance". (''Ibid.'', § 4) The world of individual objects, in this way of thinking, has no worth and should perish.

Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (; ; 26 September 188926 May 1976) was a German philosopher who is best known for contributions to phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. He is among the most important and influential philosophers of the 20th centur ...

lectured extensively on Anaximander, and delivered a lecture entitled "Anaximander's Saying" which was subsequently included in ''Off the Beaten Track''. The lecture examines the ontological difference and the oblivion of Being or ''Dasein

''Dasein'' () (sometimes spelled as Da-sein) is the German word for 'existence'. It is a fundamental concept in the existential philosophy of Martin Heidegger. Heidegger uses the expression ''Dasein'' to refer to the experience of being that is p ...

'' in the context of the Anaximander fragment. Heidegger's lecture is, in turn, an important influence on the French philosopher Jacques Derrida

Jacques Derrida (; ; born Jackie Élie Derrida; See also . 15 July 1930 – 9 October 2004) was an Algerian-born French philosopher. He developed the philosophy of deconstruction, which he utilized in numerous texts, and which was developed t ...

.

Works

According to the ''Suda'':Themistius and Simplicius also mention some work "on nature". The list could refer to book titles or simply their topics. Again, no one can tell because there is no punctuation sign in Ancient Greek. Furthermore, this list is incomplete since the ''Suda'' ends it with , thus implying "other works". * '' On Nature'' ( / ''Perì phúseôs'') * ''Rotation of the Earth'' ( / ''Gễs períodos'') * ''On Fixed stars'' ( / ''Perì tỗn aplanỗn'') * ''The elestialSphere'' ( / ''Sphaĩra'')See also

*Material monism

Material monism is a Pre-Socratic belief which provides an explanation of the physical world by saying that all of the world's objects are composed of a single element.

Among the material monists were the three Milesian philosophers: Thales, who ...

* Indefinite monism

Indefinite Monism is a philosophical conception of reality that asserts that only Awareness is real and that the wholeness of Reality can be conceptually thought of in terms of immanent and transcendent aspects. The immanent aspect is denominate ...

Footnotes

References

Primary sources

* Aelian: ''Various History'' (III, 17) * Aëtius: ''De Fide'' (I-III; V) *Agathemerus

Agathemerus (Greek: ) was a Greek geographer who during the Roman Greece period published a small two-part geographical work titled ''A Sketch of Geography in Epitome'' (), addressed to his pupil Philon. The son of Orthon, Agathemerus is specula ...

: ''A Sketch of Geography in Epitome'' (I, 1)

* Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

: ''Meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did not ...

'' (II, 3) Translated bE. W. Webster

* Aristotle: ''

On Generation and Corruption

''On Generation and Corruption'' ( grc, Περὶ γενέσεως καὶ φθορᾶς; la, De Generatione et Corruptione), also known as ''On Coming to Be and Passing Away'' is a treatise by Aristotle. Like many of his texts, it is both scie ...

'' (II, 5) Translated bH. H. Joachim

* Aristotle: ''

On the Heavens

''On the Heavens'' (Greek: ''Περὶ οὐρανοῦ''; Latin: ''De Caelo'' or ''De Caelo et Mundo'') is Aristotle's chief cosmological treatise: written in 350 BC, it contains his astronomical theory and his ideas on the concrete workings o ...

'' (II, 13) Translated bJ. L. Stocks

* (III, 5, 204 b 33–34) *

Censorinus

Censorinus was a Roman grammarian and miscellaneous writer from the 3rd century AD.

Biography

He was the author of a lost work ''De Accentibus'' and of an extant treatise ''De Die Natali'', written in 238, and dedicated to his patron Quintus ...

: ''De Die Natali'' (IV, 7) See original text aLacusCurtius

* (I, 50, 112) * Cicero: ''On the Nature of the Gods'' (I, 10, 25) * *

Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Εὐριπίδης, Eurīpídēs, ; ) was a tragedian

Tragedy (from the grc-gre, τραγῳδία, ''tragōidia'', ''tragōidia'') is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful e ...

: '' The Suppliants'' (532) Translated bE. P. Coleridge

*

Eusebius of Caesarea

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christia ...

: '' Preparation for the Gospel'' (X, 14, 11) Translated bE.H. Gifford

* Heidel, W.A. ''Anaximander's Book'': PAAAS, vol. 56, n.7, 1921, pp. 239–288. *

Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

: '' Histories'' (II, 109) See original text iPerseus project

* Hippolytus (?): ''Refutation of All Heresies'' (I, 5) Translated b

Roberts and Donaldson

*

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

: '' Natural History'' (II, 8) See original text iPerseus project

*

Pseudo-Plutarch Pseudo-Plutarch is the conventional name given to the actual, but unknown, authors of a number of pseudepigrapha (falsely attributed works) attributed to Plutarch but now known to have not been written by him.

Some of these works were included in s ...

: ''The Doctrines of the Philosophers'' (I, 3; I, 7; II, 20–28; III, 2–16; V, 19)

* Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger (; 65 AD), usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, dramatist, and, in one work, satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Seneca was born in ...

: ''Natural Questions'' (II, 18)

* Simplicius: ''Comments on Aristotle's Physics'' (24, 13–25; 1121, 5–9)

* Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

: ''Geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and ...

'' (I, 1) Books 1‑7, 15‑17 translated bH. L. Jones

*

Themistius

Themistius ( grc-gre, Θεμίστιος ; 317 – c. 388 AD), nicknamed Euphrades, (eloquent), was a statesman, rhetorician, and philosopher. He flourished in the reigns of Constantius II, Julian, Jovian, Valens, Gratian, and Theodosius I; ...

: ''Oratio'' (36, 317)

* ''The Suda

The ''Suda'' or ''Souda'' (; grc-x-medieval, Σοῦδα, Soûda; la, Suidae Lexicon) is a large 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Soudas (Σούδας) or Souidas ...

''''Suda On Line''

Secondary sources

* * * The default source; anything not otherwise attributed should be in Conche. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* *((Grk icon))

*

Life and Work - Fragments and Testimonies by Giannis Stamatellos {{Authority control 6th-century BC Greek people 6th-century BC philosophers 610s BC births 540s BC deaths Ancient Greek astronomers Ancient Greek cartographers Ancient Greek metaphysicians Ancient Greek physicists Ancient Greeks from the Achaemenid Empire Ancient Milesians Natural philosophers Philosophers of ancient Ionia Presocratic philosophers 6th-century BC geographers