Anarcho Communism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of

Bob Black. ''Nightmares of Reason''

. Most anarcho-communists view anarcho-communism as a way of reconciling the opposition between the individual and society. L. Susan Brown, '' The Politics of Individualism'', Black Rose Books (2002). L. Susan Brown

"Does Work Really Work?"

. Anarcho-communism developed out of

As a coherent, modern economic-political philosophy, anarcho-communism was first formulated in the Italian section of the First International by Carlo Cafiero,

As a coherent, modern economic-political philosophy, anarcho-communism was first formulated in the Italian section of the First International by Carlo Cafiero,  In ''Anarchy and Communism'' (1880), Carlo Cafiero explains that

In ''Anarchy and Communism'' (1880), Carlo Cafiero explains that

Chapter IX The Need For Luxury

He maintained that in anarcho-communism, "houses, fields, and factories will no longer be

Chapter 13 ''The Collectivist Wages System'' from ''The Conquest of Bread''

, G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York and London, 1906. Individuals and groups would use and control whatever resources they needed, as the aim of anarchist communism was to place "the product reaped or manufactured at the disposal of all, leaving to each the liberty to consume them as he pleases in his own home". He supported the expropriation of

Individuals and groups would use and control whatever resources they needed, as the aim of anarchist communism was to place "the product reaped or manufactured at the disposal of all, leaving to each the liberty to consume them as he pleases in his own home". He supported the expropriation of

Between 1880 and 1890, with the "perspective of an

Between 1880 and 1890, with the "perspective of an

"Against organization"

. Retrieved 6 October 2010. By the 1880s, anarcho-communism was already present in the United States, as seen in the journal ''Freedom: A Revolutionary Anarchist-Communist Monthly'' by Lucy Parsons and Lizzy Holmes."Lucy Parsons: Woman Of Will"

at the Lucy Parsons Center Lucy Parsons debated in her time in the United States with fellow anarcho-communist

In Ukraine, the anarcho-communist guerrilla leader Nestor Makhno led an independent anarchist army during the Russian Civil War. A commander of the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine, Makhno led a guerrilla campaign opposing both the Bolshevik "Reds" and monarchist "Whites". The Makhnovist movement made various tactical military pacts while fighting various reaction forces and organizing an anarchist society committed to resisting state authority, whether capitalist or Bolshevik. After successfully repelling Austro-Hungarian, White, and Ukrainian Nationalist forces, the Makhnovists militia and anarchist communist territories in Ukraine were eventually crushed by Bolshevik military forces.

In the

In Ukraine, the anarcho-communist guerrilla leader Nestor Makhno led an independent anarchist army during the Russian Civil War. A commander of the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine, Makhno led a guerrilla campaign opposing both the Bolshevik "Reds" and monarchist "Whites". The Makhnovist movement made various tactical military pacts while fighting various reaction forces and organizing an anarchist society committed to resisting state authority, whether capitalist or Bolshevik. After successfully repelling Austro-Hungarian, White, and Ukrainian Nationalist forces, the Makhnovists militia and anarchist communist territories in Ukraine were eventually crushed by Bolshevik military forces.

In the  Two texts made by the anarchist communists Sébastien Faure and Volin as responses to the Platform, each proposing different models, are the basis for what became known as the organization of synthesis, or simply

Two texts made by the anarchist communists Sébastien Faure and Volin as responses to the Platform, each proposing different models, are the basis for what became known as the organization of synthesis, or simply

The Korean Anarchist Movement in Korea, led by Kim Chwa-chin, briefly brought anarcho-communism to Korea. The success was short-lived and much less widespread than the anarchism in Spain. The Korean People's Association in Manchuria had established a stateless,

The Korean Anarchist Movement in Korea, led by Kim Chwa-chin, briefly brought anarcho-communism to Korea. The success was short-lived and much less widespread than the anarchism in Spain. The Korean People's Association in Manchuria had established a stateless,

The most extensive application of anarcho-communist ideas (i.e., established around the ideas as they exist today and achieving worldwide attention and knowledge in the historical canon) happened in the anarchist territories during the Spanish Revolution.

The most extensive application of anarcho-communist ideas (i.e., established around the ideas as they exist today and achieving worldwide attention and knowledge in the historical canon) happened in the anarchist territories during the Spanish Revolution.

In Spain, the national anarcho-syndicalist trade union Confederación Nacional del Trabajo initially refused to join a popular front electoral alliance, and abstention by CNT supporters led to a right-wing election victory. In 1936, the CNT changed its policy, and anarchist votes helped bring the popular front back to power. Months later, the former ruling class responded with an attempted coup causing the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). In response to the army rebellion, an anarchist-inspired movement of peasants and workers, supported by armed militias, took control of Barcelona and large areas of rural Spain, where they collectivized the land. However, even before the fascist victory in 1939, the anarchists were losing ground in a bitter struggle with the Stalinists, who controlled the distribution of military aid to the Republican cause from the Soviet Union. The events known as the Spanish Revolution was a workers'

In Spain, the national anarcho-syndicalist trade union Confederación Nacional del Trabajo initially refused to join a popular front electoral alliance, and abstention by CNT supporters led to a right-wing election victory. In 1936, the CNT changed its policy, and anarchist votes helped bring the popular front back to power. Months later, the former ruling class responded with an attempted coup causing the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). In response to the army rebellion, an anarchist-inspired movement of peasants and workers, supported by armed militias, took control of Barcelona and large areas of rural Spain, where they collectivized the land. However, even before the fascist victory in 1939, the anarchists were losing ground in a bitter struggle with the Stalinists, who controlled the distribution of military aid to the Republican cause from the Soviet Union. The events known as the Spanish Revolution was a workers'  Although every sector of the stateless parts of Spain had undergone workers' self-management, collectivization of agricultural and industrial production, and in parts using money or some degree of private property, heavy regulation of markets by democratic communities, other areas throughout Spain used no money at all, and followed principles in accordance with " From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs". One such example was the libertarian communist village of Alcora in the Valencian Community, where money was absent, and the distribution of properties and services was done based upon needs, not who could afford them.

Although every sector of the stateless parts of Spain had undergone workers' self-management, collectivization of agricultural and industrial production, and in parts using money or some degree of private property, heavy regulation of markets by democratic communities, other areas throughout Spain used no money at all, and followed principles in accordance with " From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs". One such example was the libertarian communist village of Alcora in the Valencian Community, where money was absent, and the distribution of properties and services was done based upon needs, not who could afford them.

/ref> The ''Manifesto of Libertarian Communism'' was written in 1953 by Georges Fontenis for the ''Federation Communiste Libertaire'' of France. It is one of the key texts of the anarchist-communist current known as platformism. The OPB pushed for a move that saw the FA change its name to the (FCL) after the 1953 Congress in Paris, while an article in indicated the end of the cooperation with the French Surrealist Group led by

The Informal Anarchist Federation (not to be confused with the synthesist Italian Anarchist Federation, also FAI) is an Italian insurrectionary anarchist organization. Italian intelligence sources have described it as a "horizontal" structure of various anarchist terrorist groups, united in their beliefs in revolutionary armed action. In 2003, the group claimed responsibility for a bombing campaign targeting several European Union institutions. Currently, alongside the previously mentioned federations, the International of Anarchist Federations includes the

Communist anarchism shares many traits with

Communist anarchism shares many traits with

In anthropology and the social sciences, a gift economy (or gift culture) is a mode of exchange where valuable goods and services are regularly given without explicit agreement for immediate or future rewards (i.e., no formal ''

In anthropology and the social sciences, a gift economy (or gift culture) is a mode of exchange where valuable goods and services are regularly given without explicit agreement for immediate or future rewards (i.e., no formal ''

Anarchist communists counter the capitalist conception that communal property can only be maintained by force and that such a position is neither fixed in nature nor unchangeable in practice, citing numerous examples of communal behavior occurring naturally, even within capitalist systems. Anarchist communists call for the abolition of

Anarchist communists counter the capitalist conception that communal property can only be maintained by force and that such a position is neither fixed in nature nor unchangeable in practice, citing numerous examples of communal behavior occurring naturally, even within capitalist systems. Anarchist communists call for the abolition of

What is Communist Anarchism?

', ''Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist'', others. *

Revolution.

' Black Cat Press. . *

Anarchism and Communism

' *

Anarchist Communists: A Question Of Class

', others * Ricardo Flores Magón

Dreams of Freedom: A Ricardo Flores Magón Reader

'. Chaz Bufe and Mitchell Cowen Verter (ed.) 2005. * Georges Fontenis.

Manifesto of Libertarian Communism

' *

Anarchism and Other Essays

', ''Living My Life'', others. * Robert Graham, '' Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas'', Volume 1: From Anarchy to Anarchism (300 CE–1939)() contains extensive selections from the anarchist communists, including Joseph Déjacque, Carlo Cafiero, Peter Kropotkin, Luigi Galleani, Errico Malatesta,

Communism and Anarchy

' *

The Organizational Platform of the Libertarian Communists

' (available in: Castellano, čeština, Deutsch, English, Έλληνικά, Français, Italiano, Ivrit, Magyar, Nederlands, Polska, Português, Pyccкий, Svenska, Türkçe, Македонски). *

A Talk About Anarchist Communism Between Two Workers

' * Jessica Moran.

The Firebrand and the Forging of a New Anarchism: Anarchist Communism and Free Love.

* Johann Most

"Anarchist Communism"

* Alain Pengam

* Isaac Puente

Libertarian Communism

' * Ilan Shalif

* Michael Schmidt and Lucien van der Walt. ''[https://web.archive.org/web/20171119063336/http://www.revolutionbythebook.akpress.org/black-flame-the-revolutionary-class-politics-of-anarchism-and-syndicalism-%E2%80%94-book-excerpt/ Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism]''

AK Press

2009. *

The Rise and Fall of The Green Mountain Anarchist Collective

', 2015.

Anarkismo.net

– anarchist communist news maintained by platformist organizations with discussion and theory from across the globe

Anarchocommunism texts at The Anarchist Library

Kropotkin: The Coming Revolution

– short documentary to introduce the idea of anarcho-communism in Peter Kropotkin's own words ; Anarcho-communist theorist archives

Alexander Berkman

Luigi Galleani

Emma Goldman

Peter Kropotkin

Ricardo Flores Magón

Errico Malatesta

Nestor Makhno

Johann Most

Lucien van der Walt

{{authority control Communism Anti-capitalism Anti-fascism Communism Criticism of intellectual property Economic ideologies Far-left politics Left-libertarianism Libertarian socialism Political ideologies Social anarchism Types of socialism

private property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property and personal property, which is owned by a state entity, and from collective or ...

but retains respect for personal property

property is property that is movable. In common law systems, personal property may also be called chattels or personalty. In civil law systems, personal property is often called movable property or movables—any property that can be moved fr ...

and collectively-owned items, goods, and services. It supports social ownership of property and direct democracy

Direct democracy or pure democracy is a form of democracy in which the Election#Electorate, electorate decides on policy initiatives without legislator, elected representatives as proxies. This differs from the majority of currently establishe ...

among other horizontal networks for the allocation of production and consumption based on the guiding principle " From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs". Some forms of anarcho-communism, such as insurrectionary anarchism, are strongly influenced by egoism and radical individualism, believing anarcho-communism to be the best social system for realizing individual freedom."Towards the creative Nothing" byRenzo Novatore

Abele Rizieri Ferrari (May 12, 1890 – November 29, 1922), better known by the pen name Renzo Novatore, was an Italian individualist anarchist, illegalist and anti-fascist poet, philosopher and militant, now mostly known for his posthumously pu ...

Post-left

Contemporary anarchism within the history of anarchism is the period of the anarchist movement continuing from the end of World War II and into the present. Since the last third of the 20th century, anarchists have been involved in anti-globalisat ...

anarcho-communist Bob Black

Robert Charles Black Jr. (born January 4, 1951) is an American anarchist and author. He is the author of the books '' The Abolition of Work and Other Essays'', ''Beneath the Underground'', ''Friendly Fire'', ''Anarchy After Leftism'', and ''Def ...

after analysing insurrectionary

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

anarcho-communist Luigi Galleani

Luigi Galleani (; 1861–1931) was an Italian anarchist active in the United States from 1901 to 1919. He is best known for his enthusiastic advocacy of "propaganda of the deed", i.e. the use of violence to eliminate those he viewed as tyrants ...

's view on anarcho-communism went as far as saying that "communism is the final fulfillment of individualism...The apparent contradiction between individualism and communism rests on a misunderstanding of both...Subjectivity is also objective: the individual really is subjective. It is nonsense to speak of "emphatically prioritizing the social over the individual,"...You may as well speak of prioritizing the chicken over the egg. Anarchy is a "method of individualization." It aims to combine the greatest individual development with the greatest communal unityBob Black. ''Nightmares of Reason''

. Most anarcho-communists view anarcho-communism as a way of reconciling the opposition between the individual and society. L. Susan Brown, '' The Politics of Individualism'', Black Rose Books (2002). L. Susan Brown

"Does Work Really Work?"

. Anarcho-communism developed out of

radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

socialist currents after the French Revolution, but it was first formulated as such in the Italian section of the First International. The theoretical work of Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activis ...

took importance later as it expanded and developed pro-organizationalist and insurrectionary anti-organizationalist sections. To date, the best-known examples of anarcho-communist societies (i.e., established around the ideas as they exist today and achieving worldwide attention and knowledge in the historical canon) are the anarchist territories during the Spanish Revolution and the Makhnovshchina during the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

, where anarchists such as Nestor Makhno worked to create and defend anarcho-communism through the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine.

In 1929, anarcho-communism was implemented in Korea by the Korean Anarchist Federation in Manchuria (KAFM) and the Korean Anarcho-Communist Federation (KACF), with help from anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

general and independence activist

Activism (or Advocacy) consists of efforts to promote, impede, direct or intervene in social, political, economic or environmental reform with the desire to make changes in society toward a perceived greater good. Forms of activism range fro ...

Kim Chwa-chin, lasting until 1931, when Imperial Japan assassinated Kim and invaded from the south, while the Chinese Nationalists invaded from the north, resulting in the creation of Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Northeast China, Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 afte ...

, a puppet state of the Empire of Japan. Through the efforts and influence of the Spanish anarchists during the Spanish Revolution within the Spanish Civil War starting in 1936, anarcho-communism existed in most of Aragon, parts of the Levante and Andalusia, as well as in the stronghold of anarchist Catalonia. In 1939, these anarcho-communists were crushed by the combined forces of the Francoist Nationalists (the regime that won the war), Nationalist allies such as Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

, and even Spanish Communist Party repression (backed by the Soviet Union), as well as economic and armaments blockades from the capitalist states and the Spanish Republic itself governed by the Republicans

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

.

History

Early precursors

Early Christian

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish d ...

communities have also been described as having anarcho-communist characteristics. Frank Seaver Billings described " Jesusism" as a combination of anarchism and communism. Examples of later Christian egalitarian communities include the Diggers in England. Gerrard Winstanley, who was part of the Diggers movement, wrote in his 1649 pamphlet ''The New Law of Righteousness'' that there "shall be no buying or selling, no fairs nor markets, but the whole earth shall be a common treasury for every man" and "there shall be none Lord over others, but every one shall be a Lord of himself".

The Diggers resisted the tyranny of the ruling class and kings, instead operating cooperatively to get work done, manage supplies, and increase economic productivity. Due to the communes established by the Diggers being free from private property, along with economic exchange (all items, goods, and services were held collectively), their communes could be called early, functioning communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

societies, spread out across the rural lands of England. Before the Industrial Revolution, common ownership of land and property was much more prevalent across the European continent, but the Diggers were set apart by their struggle against monarchical rule. They sprung up using workers' self-management after the fall of Charles I.

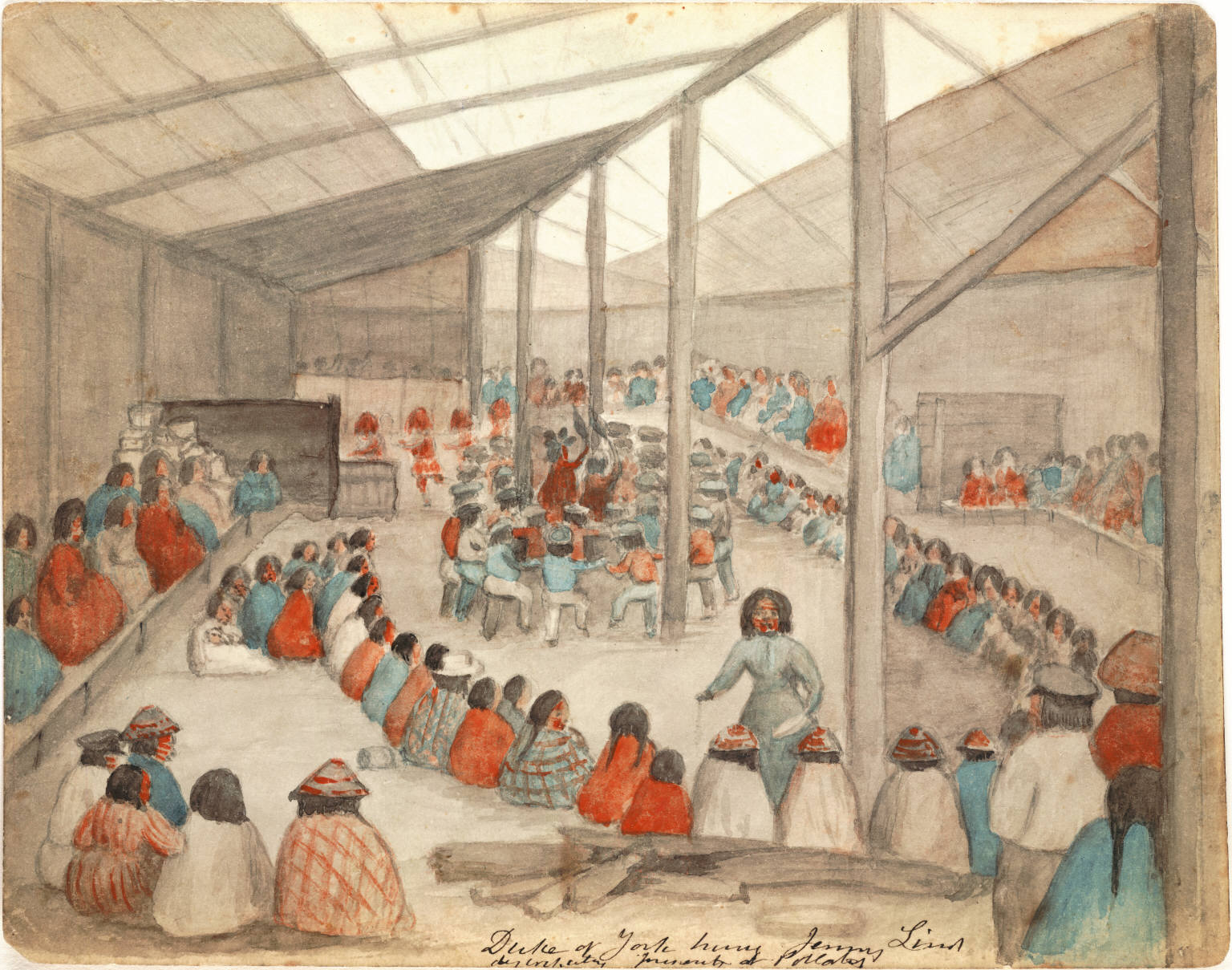

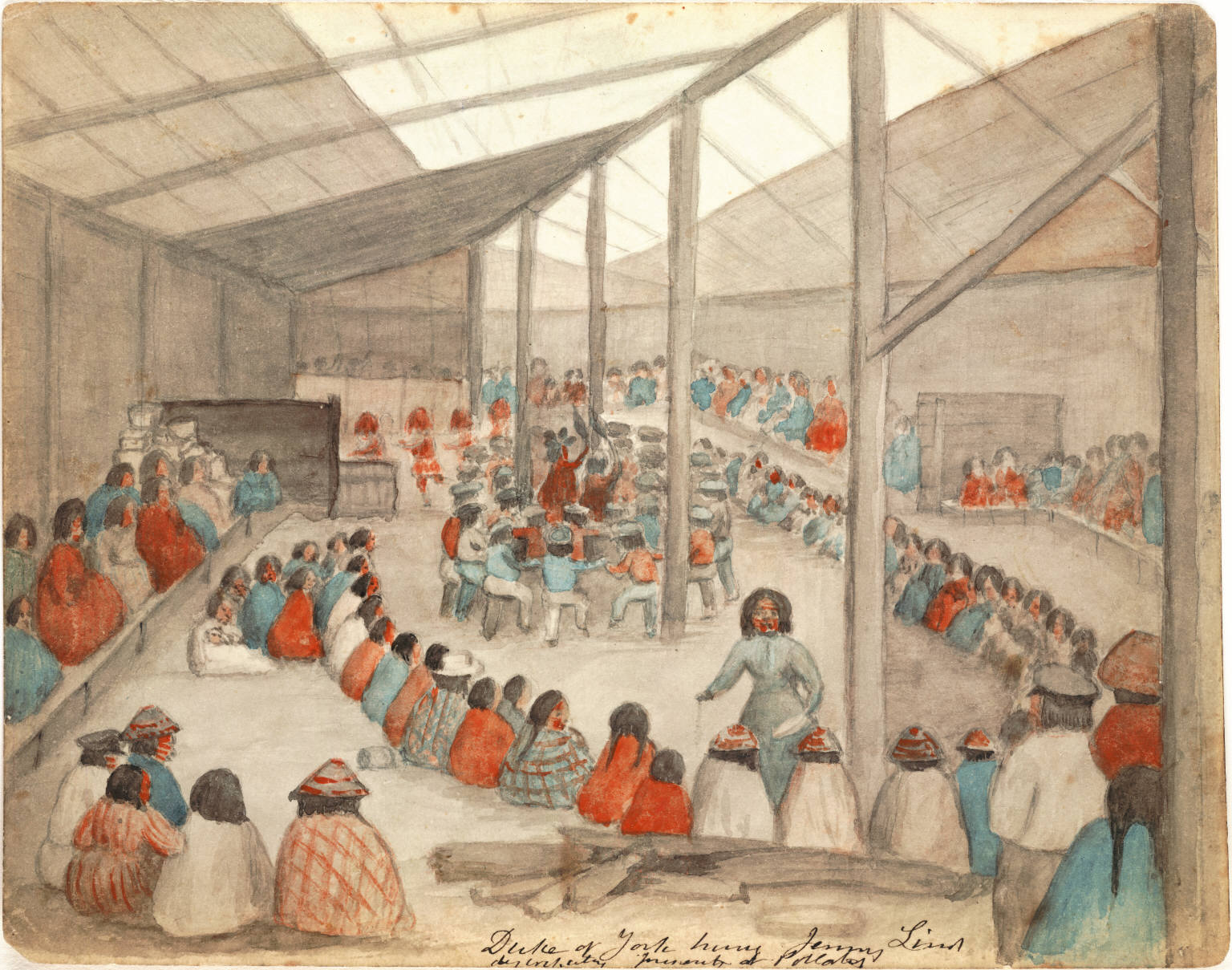

In 1703, Louis Armand, Baron de Lahontan, wrote the novel ''New Voyages to North America ''New Voyages to North America'' is a book by Louis-Armand de Lom d'Arce de Lahontan, Baron de Lahontan, Louis Armand de Lom d’Arce, baron de Lahontan that chronicles his nine years exploring New France as a soldier in the French Army. Published i ...

,'' where he outlined how indigenous communities of the North American continent cooperated and organized. The author found the agrarian societies and communities of pre-colonial North America to be nothing like the monarchical, unequal states of Europe, both in their economic structure and lack of any state. He wrote that the life natives lived was "anarchy", this being the first usage of the term to mean something other than chaos. He wrote that there were no priests, courts, laws, police, ministers of state, and no distinction of property, no way to differentiate rich from poor, as they were all equal and thriving cooperatively.

During the French Revolution, Sylvain Maréchal

Sylvain Maréchal (15 August 1750 – 18 January 1803) was a French essayist, poet, philosopher and political theorist, whose views presaged utopian socialism and communism. His views on a future golden age are occasionally described as ''utopian ...

, in his ''Manifesto of the Equals'' (1796), demanded "the communal enjoyment of the fruits of the earth" and looked forward to the disappearance of "the revolting distinction of rich and poor, of great and small, of masters and valets, of governors and governed".

Joseph Déjacque and the Revolutions of 1848

Joseph Déjacque, unlike Proudhon, argued that "it is not the product of his or her labor that the worker has a right to, but to the satisfaction of his or her needs, whatever may be their nature". According to the anarchist historianMax Nettlau

Max Heinrich Hermann Reinhardt Nettlau (; 30 April 1865 – 23 July 1944) was a German anarchist and historian. Although born in Neuwaldegg (today part of Vienna) and raised in Vienna, he lived there until the anschluss to Nazi Germany in 193 ...

, the first use of the term libertarian communism was in November 1880, when a French anarchist congress employed it to identify its doctrines more clearly. The French anarchist journalist Sébastien Faure, later founder and editor of the four-volume '' Anarchist Encyclopedia,'' started the weekly paper (''The Libertarian'') in 1895.

International Workingmen's Association

As a coherent, modern economic-political philosophy, anarcho-communism was first formulated in the Italian section of the First International by Carlo Cafiero,

As a coherent, modern economic-political philosophy, anarcho-communism was first formulated in the Italian section of the First International by Carlo Cafiero, Emilio Covelli

Emilio Covelli (1846–1915) was an Italian anarchist and socialist who together with Carlo Cafiero was one of the most important figures in the early socialist movement in Italy, a member of the International Workingmen's Association, or "First ...

, Errico Malatesta

Errico Malatesta (4 December 1853 – 22 July 1932) was an Italian anarchist propagandist and revolutionary socialist. He edited several radical newspapers and spent much of his life exiled and imprisoned, having been jailed and expelled from ...

, Andrea Costa, and other ex-Mazzinian

Giuseppe Mazzini (, , ; 22 June 1805 – 10 March 1872) was an Italian politician, journalist, and activist for the unification of Italy (Risorgimento) and spearhead of the Italian revolutionary movement. His efforts helped bring about the i ...

republicans. Collectivist anarchists advocated remuneration for the type and amount of labor adhering to the principle "to each according to deeds" but held out the possibility of a post-revolutionary transition to a communist distribution system according to need. As Mikhail Bakunin's associate James Guillaume put it in his essay ''Ideas on Social Organization'' (1876): "When ..production comes to outstrip consumption ..everyone will draw what he needs from the abundant social reserve of commodities, without fear of depletion; and the moral sentiment which will be more highly developed among free and equal workers will prevent, or greatly reduce, abuse and waste".

The collectivist anarchists sought to collectivize ownership of the means of production while retaining payment proportional to the amount and kind of labor of each individual, but the anarcho-communists sought to extend the concept of collective ownership to the products of labor as well. While both groups argued against capitalism, the anarchist communists departed from Proudhon and Bakunin, who maintained that individuals have a right to the product of their labor and to be remunerated for their particular contribution to production. However, Errico Malatesta stated, "instead of running the risk of making a confusion in trying to distinguish what you and I each do, let us all work and put everything in common. In this way each will give to society all that his strength permits until enough is produced for every one; and each will take all that he needs, limiting his needs only in those things of which there is not yet plenty for every one".

In ''Anarchy and Communism'' (1880), Carlo Cafiero explains that

In ''Anarchy and Communism'' (1880), Carlo Cafiero explains that private property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property and personal property, which is owned by a state entity, and from collective or ...

in the product of labor will lead to unequal accumulation of capital and, therefore, the reappearance of social classes and their antagonisms; and thus the resurrection of the state: "If we preserve the individual appropriation of the products of labour, we would be forced to preserve money, leaving more or less accumulation of wealth according to more or less merit rather than need of individuals". At the Florence Conference of the Italian Federation of the International in 1876, held in a forest outside Florence due to police activity, they declared the principles of anarcho-communism as follows:

The above report was made in an article by Malatesta and Cafiero in the Swiss Jura Federation's bulletin later that year.

Peter Kropotkin

Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activis ...

(1842–1921), often seen as the most important theorist of anarchist communism, outlined his economic ideas in '' The Conquest of Bread'' and '' Fields, Factories and Workshops''. Kropotkin felt that cooperation is more beneficial than competition, arguing in his major scientific work '' Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution'' that this was well-illustrated in nature. He advocated the abolition of private property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property and personal property, which is owned by a state entity, and from collective or ...

(while retaining respect for personal property

property is property that is movable. In common law systems, personal property may also be called chattels or personalty. In civil law systems, personal property is often called movable property or movables—any property that can be moved fr ...

) through the "expropriation of the whole of social wealth" by the people themselvesPeter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activis ...

, ''Words of a Rebel'', p99. and for the economy to be co-ordinated through a horizontal network of voluntary associationsPeter Kropotkin, '' The Conquest of Bread'', p145. where goods are distributed according to the physical needs of the individual, rather than according to labor.Marshall Shatz, Introduction to Kropotkin: The Conquest of Bread and Other Writings, Cambridge University Press 1995, p. xvi "Anarchist communism called for the socialization not only of production but of the distribution of goods: the community would supply the subsistence requirements of each individual member free of charge, and the criterion, 'to each according to his labor' would be superseded by the criterion 'to each according to his needs.'" He further argued that these "needs," as society progressed, would not merely be physical but " soon as his material wants are satisfied, other needs, of an artistic character, will thrust themselves forward the more ardently. Aims of life vary with each and every individual; and the more society is civilized, the more will individuality be developed, and the more will desires be varied."Peter Kropotkin, ''The Conquest of Bread'Chapter IX The Need For Luxury

He maintained that in anarcho-communism, "houses, fields, and factories will no longer be

private property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property and personal property, which is owned by a state entity, and from collective or ...

, and that they will belong to the commune or the nation and money, wages, and trade would be abolished".Kropotkin, PeteChapter 13 ''The Collectivist Wages System'' from ''The Conquest of Bread''

, G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York and London, 1906.

Individuals and groups would use and control whatever resources they needed, as the aim of anarchist communism was to place "the product reaped or manufactured at the disposal of all, leaving to each the liberty to consume them as he pleases in his own home". He supported the expropriation of

Individuals and groups would use and control whatever resources they needed, as the aim of anarchist communism was to place "the product reaped or manufactured at the disposal of all, leaving to each the liberty to consume them as he pleases in his own home". He supported the expropriation of private property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property and personal property, which is owned by a state entity, and from collective or ...

into the commons or public goods (while retaining respect for personal property

property is property that is movable. In common law systems, personal property may also be called chattels or personalty. In civil law systems, personal property is often called movable property or movables—any property that can be moved fr ...

) to ensure that everyone would have access to what they needed without being forced to sell their labor to get it, arguing:

He said that a "peasant who is in possession of just the amount of land he can cultivate" and "a family inhabiting a house which affords them just enough space ..considered necessary for that number of people" and the artisan "working with their own tools or handloom" would not be interfered with,Kropotkin ''Act for yourselves.'' N. Walter and H. Becker, eds. (London: Freedom Press 1985) p. 104–105 P. is an abbreviation or acronym that may refer to:

* Page (paper), where the abbreviation comes from Latin ''pagina''

* Paris Herbarium, at the ''Muséum national d'histoire naturelle''

* ''Pani'' (Polish), translating as Mrs.

* The ''Pacific Repo ...

/ref> arguing that " e landlord owes his riches to the poverty of the peasants, and the wealth of the capitalist comes from the same source".

In summation, Kropotkin described an anarchist communist economy as functioning like this:

Organizationalism vs. insurrectionarism and expansion

At the Berne conference of the International Workingmen's Association in 1876, the Italian anarchistErrico Malatesta

Errico Malatesta (4 December 1853 – 22 July 1932) was an Italian anarchist propagandist and revolutionary socialist. He edited several radical newspapers and spent much of his life exiled and imprisoned, having been jailed and expelled from ...

argued that the revolution "consists more of deeds than words" and that action was the most effective form of propaganda. In the bulletin of the Jura Federation, he declared, "the Italian federation believes that the insurrectional fact, destined to affirm socialist principles by deed, is the most efficacious means of propaganda".

As anarcho-communism emerged in the mid-19th century, it had an intense debate with Bakuninist

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary s ...

collectivism and, within the anarchist movement, over participation in syndicalism and the workers' movement, as well as on other issues. So in "the theory of the revolution" of anarcho-communism as elaborated by Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activis ...

and others, "it is the risen people who are the real agent and not the working class organised in the enterprise (the cells of the capitalist mode of production) and seeking to assert itself as labour power, as a more 'rational' industrial body or social brain (manager) than the employers".

Between 1880 and 1890, with the "perspective of an

Between 1880 and 1890, with the "perspective of an immanent

The doctrine or theory of immanence holds that the divine encompasses or is manifested in the material world. It is held by some philosophical and metaphysical theories of divine presence. Immanence is usually applied in monotheistic, pantheis ...

revolution", who was "opposed to the official workers' movement, which was then in the process of formation (general Social Democratisation). They were opposed not only to political (statist) struggles but also to strikes which put forward wage or other claims, or which were organised by trade unions." However, " ile they were not opposed to strikes as such, they were opposed to trade unions and the struggle for the eight-hour day. This anti-reformist tendency was accompanied by an anti-organisational tendency, and its partisans declared themselves in favor of agitation amongst the unemployed for the expropriation of foodstuffs and other articles, for the expropriatory strike and, in some cases, for 'individual recuperation

The following is a list of terms specific to anarchists. Anarchism is a political and social movement which advocates voluntary association in opposition to authoritarianism and hierarchy.

__NOTOC__

A

:The negation of rule or "government by ...

' or acts of terrorism."

Even after Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activis ...

and others overcame their initial reservations and decided to enter labor union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

s, there remained "the anti-syndicalist anarchist-communists, who in France were grouped around Sébastien Faure's ''Le Libertaire''. From 1905 onwards, the Russian counterparts of these anti-syndicalist anarchist-communists become partisans of economic terrorism and illegal ' expropriations'." Illegalism as a practice emerged, and within it, " e acts of the anarchist bombers and assassins (" propaganda by the deed") and the anarchist burglars (" individual reappropriation") expressed their desperation and their personal, violent rejection of an intolerable society. Moreover, they were clearly meant to be exemplary, invitations to revolt."

Proponents and activists of these tactics, among others, included Johann Most, Luigi Galleani

Luigi Galleani (; 1861–1931) was an Italian anarchist active in the United States from 1901 to 1919. He is best known for his enthusiastic advocacy of "propaganda of the deed", i.e. the use of violence to eliminate those he viewed as tyrants ...

, Victor Serge, Giuseppe Ciancabilla Giuseppe Ciancabilla was one of the important figures of the anarchist movement who immigrated to the United States in the late 19th century, along with F. Saverio Merlino, Pietro Gori, Carlo Tresca, and Luigi Galleani.

Life

According to histo ...

, and Severino Di Giovanni. The Italian Giuseppe Ciancabilla Giuseppe Ciancabilla was one of the important figures of the anarchist movement who immigrated to the United States in the late 19th century, along with F. Saverio Merlino, Pietro Gori, Carlo Tresca, and Luigi Galleani.

Life

According to histo ...

(1872–1904) wrote in "Against organization" that "we don't want tactical programs, and consequently we don't want organization. Having established the aim, the goal to which we hold, we leave every anarchist free to choose from the means that his sense, his education, his temperament, his fighting spirit suggest to him as best. We don't form fixed programs and we don't form small or great parties. But we come together spontaneously, and not with permanent criteria, according to momentary affinities for a specific purpose, and we constantly change these groups as soon as the purpose for which we had associated ceases to be, and other aims and needs arise and develop in us and push us to seek new collaborators, people who think as we do in the specific circumstance."Ciancabilla, Giuseppe"Against organization"

. Retrieved 6 October 2010. By the 1880s, anarcho-communism was already present in the United States, as seen in the journal ''Freedom: A Revolutionary Anarchist-Communist Monthly'' by Lucy Parsons and Lizzy Holmes."Lucy Parsons: Woman Of Will"

at the Lucy Parsons Center Lucy Parsons debated in her time in the United States with fellow anarcho-communist

Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the ...

over free love and feminism issues. Another anarcho-communist journal later appeared in the United States called '' The Firebrand''. Most anarchist publications in the United States were in Yiddish, German, or Russian, but ''Free Society'' was published in English, permitting the dissemination of anarchist communist thought to English-speaking populations in the United States."''Free Society'' was the principal English-language forum for anarchist ideas in the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century." ''Emma Goldman: Making Speech Free, 1902–1909'', p. 551. Around that time, these American anarcho-communist sectors debated with the individualist anarchist

Individualist anarchism is the branch of anarchism that emphasizes the individual and their Will (philosophy), will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions and ideological systems."What do I mean by individualism? I mean ...

group around Benjamin Tucker. In February 1888, Berkman left for the United States from his native Russia.Avrich, ''Anarchist Portraits'', p. 202. Soon after he arrived in New York City, Berkman became an anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

through his involvement with groups that had formed to campaign to free the men convicted of the 1886 Haymarket bombing

The Haymarket affair, also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, the Haymarket Square riot, or the Haymarket Incident, was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886, at Haymarket Square i ...

.Pateman, p. iii. He, as well as Emma Goldman, soon came under the influence of Johann Most, the best-known anarchist in the United States; and an advocate of propaganda of the deed—''attentat'', or violence carried out to encourage the masses to revolt.Walter, p. vii. Berkman became a typesetter for Most's newspaper .

According to anarchist historian Max Nettlau

Max Heinrich Hermann Reinhardt Nettlau (; 30 April 1865 – 23 July 1944) was a German anarchist and historian. Although born in Neuwaldegg (today part of Vienna) and raised in Vienna, he lived there until the anschluss to Nazi Germany in 193 ...

, the first use of the term ''libertarian communism'' was in November 1880, when a French anarchist congress employed it to identify its doctrines more clearly. The French anarchist journalist Sébastien Faure started the weekly paper (''The Libertarian'') in 1895.

Methods of organizing: platformism vs. synthesism

In Ukraine, the anarcho-communist guerrilla leader Nestor Makhno led an independent anarchist army during the Russian Civil War. A commander of the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine, Makhno led a guerrilla campaign opposing both the Bolshevik "Reds" and monarchist "Whites". The Makhnovist movement made various tactical military pacts while fighting various reaction forces and organizing an anarchist society committed to resisting state authority, whether capitalist or Bolshevik. After successfully repelling Austro-Hungarian, White, and Ukrainian Nationalist forces, the Makhnovists militia and anarchist communist territories in Ukraine were eventually crushed by Bolshevik military forces.

In the

In Ukraine, the anarcho-communist guerrilla leader Nestor Makhno led an independent anarchist army during the Russian Civil War. A commander of the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine, Makhno led a guerrilla campaign opposing both the Bolshevik "Reds" and monarchist "Whites". The Makhnovist movement made various tactical military pacts while fighting various reaction forces and organizing an anarchist society committed to resisting state authority, whether capitalist or Bolshevik. After successfully repelling Austro-Hungarian, White, and Ukrainian Nationalist forces, the Makhnovists militia and anarchist communist territories in Ukraine were eventually crushed by Bolshevik military forces.

In the Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution ( es, Revolución Mexicana) was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from approximately 1910 to 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It resulted in the destruction ...

, the Mexican Liberal Party was established. During the early 1910s, it led a series of military offensives leading to the conquest and occupation of certain towns and districts in Baja California, with the leadership of anarcho-communist Ricardo Flores Magón. Kropotkin's '' The Conquest of Bread'', which Flores Magón considered a kind of anarchist bible, served as the basis for the short-lived revolutionary communes in Baja California during the Magónista Revolt of 1911. Emiliano Zapata and his army and allies, including Pancho Villa, fought for agrarian reform in Mexico during the Mexican Revolution. Specifically, they wanted to establish communal land rights for Mexico's indigenous population, which had mostly lost its land to the wealthy elite of European descent. Zapata was partly influenced by Ricardo Flores Magón. The influence of Flores Magón on Zapata can be seen in the Zapatistas' Plan de Ayala, but even more noticeably in their slogan (Zapata never used this slogan) ''Tierra y libertad'' or "land and liberty", the title and maxim of Flores Magón's most famous work. Zapata's introduction to anarchism came via a local schoolteacher, Otilio Montaño Sánchez, later a general in Zapata's army, executed on 17 May 1917, who exposed Zapata to the works of Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activis ...

and Flores Magón at the same time as Zapata was observing and beginning to participate in the struggles of the peasants for the land.

A group of exiled Russian anarchists attempted to address and explain the anarchist movement's failures during the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

. They wrote the ''Organizational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists,'' which was written in 1926 by '' Dielo Truda'' ("Workers' Cause"). The pamphlet analyzes the fundamental anarchist beliefs, a vision of an anarchist society, and recommendations on how an anarchist organization should be structured. According to the ''Platform'', the four main principles by which an anarchist organization should operate are ideological unity, tactical unity, collective action

Collective action refers to action taken together by a group of people whose goal is to enhance their condition and achieve a common objective. It is a term that has formulations and theories in many areas of the social sciences including psych ...

, and federalism

Federalism is a combined or compound mode of government that combines a general government (the central or "federal" government) with regional governments (Province, provincial, State (sub-national), state, Canton (administrative division), can ...

. The Platform argues, "We have vital need of an organization which, having attracted most of the participants in the anarchist movement, would establish a common tactical and political line for anarchism and thereby serve as a guide for the whole movement".

The Platform attracted strong criticism from many sectors of the anarchist movement of the time, including some of the most influential anarchists such as Volin, Errico Malatesta

Errico Malatesta (4 December 1853 – 22 July 1932) was an Italian anarchist propagandist and revolutionary socialist. He edited several radical newspapers and spent much of his life exiled and imprisoned, having been jailed and expelled from ...

, Luigi Fabbri

Luigi Fabbri (1877–1935) was an Italian anarchist, writer, and educator, who was charged with defeatism during World War I. He was the father of Luce Fabbri.

Selected works

*''Life of Malatesta'', translated by Adam Wight (originally publis ...

, Camillo Berneri, Max Nettlau

Max Heinrich Hermann Reinhardt Nettlau (; 30 April 1865 – 23 July 1944) was a German anarchist and historian. Although born in Neuwaldegg (today part of Vienna) and raised in Vienna, he lived there until the anschluss to Nazi Germany in 193 ...

, Alexander Berkman, Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the ...

, and Grigorii Maksimov

Grigorii Petrovich Maksimov (russian: Григо́рий Петро́вич Макси́мов; 1893–1950) was a Russian anarcho-syndicalist. From the first days of the Russian Revolution, he played a leading role in the country's syndicalist ...

. Malatesta, after initially opposing the Platform, later agreed with the Platform, confirming that the original difference of opinion was due to linguistic confusion: "I find myself more or less in agreement with their way of conceiving the anarchist organisation (being very far from the authoritarian spirit which the "Platform" seemed to reveal) and I confirm my belief that behind the linguistic differences really lie identical positions."

Two texts made by the anarchist communists Sébastien Faure and Volin as responses to the Platform, each proposing different models, are the basis for what became known as the organization of synthesis, or simply

Two texts made by the anarchist communists Sébastien Faure and Volin as responses to the Platform, each proposing different models, are the basis for what became known as the organization of synthesis, or simply synthesism

Synthesis anarchism, also known as united anarchism, is an organisational principle that seeks unity in diversity, aiming to bring together anarchists of different tendencies into a single federation. Developed mainly by the Russian anarchist V ...

. Volin published in 1924 a paper calling for "the anarchist synthesis" and was also the author of the article in Sébastien Faure's on the same topic. The primary purpose behind the synthesis was that the anarchist movement in most countries was divided into three main tendencies: communist anarchism

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains resp ...

, anarcho-syndicalism

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence in b ...

, and individualist anarchism, and so such an organization could contain anarchists of these three tendencies very well. Faure, in his text "Anarchist synthesis", has the view that "these currents were not contradictory but complementary, each having a role within anarchism: anarcho-syndicalism

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence in b ...

as the strength of the mass organizations and the best way for the practice of anarchism; libertarian communism as a proposed future society based on the distribution of the fruits of labor according to the needs of each one; anarcho-individualism as a negation of oppression and affirming the individual right to development of the individual, seeking to please them in every way. The Dielo Truda platform in Spain also met with strong criticism. Miguel Jimenez, a founding member of the Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI), summarized this as follows: too much influence in it of Marxism, it erroneously divided and reduced anarchists between individualist anarchists and anarcho-communist sections, and it wanted to unify the anarchist movement along the lines of the anarcho-communists. He saw anarchism as more complex than that, that anarchist tendencies are not mutually exclusive as the platformists saw it and that both individualist and communist views could accommodate anarchosyndicalism. Sébastian Faure had strong contacts in Spain, so his proposal had more impact on Spanish anarchists than the Dielo Truda platform, even though individualist anarchist influence in Spain was less intense than it was in France. The main goal there was reconciling anarcho-communism with anarcho-syndicalism.

Gruppo Comunista Anarchico di Firenze pointed out that during the early twentieth century, the terms ''libertarian communism'' and ''anarchist communism'' became synonymous within the international anarchist movement as a result of the close connection they had in Spain (see Anarchism in Spain) (with ''libertarian communism'' becoming the prevalent term).

Korean Anarchist Movement

The Korean Anarchist Movement in Korea, led by Kim Chwa-chin, briefly brought anarcho-communism to Korea. The success was short-lived and much less widespread than the anarchism in Spain. The Korean People's Association in Manchuria had established a stateless,

The Korean Anarchist Movement in Korea, led by Kim Chwa-chin, briefly brought anarcho-communism to Korea. The success was short-lived and much less widespread than the anarchism in Spain. The Korean People's Association in Manchuria had established a stateless, classless society

The term classless society refers to a society in which no one is born into a social class. Distinctions of wealth, income, education, culture, or social network might arise and would only be determined by individual experience and achievement ...

where all means of production were run and operated by the workers, and all possessions were held in common by the community.

Spanish Revolution of 1936

The most extensive application of anarcho-communist ideas (i.e., established around the ideas as they exist today and achieving worldwide attention and knowledge in the historical canon) happened in the anarchist territories during the Spanish Revolution.

The most extensive application of anarcho-communist ideas (i.e., established around the ideas as they exist today and achieving worldwide attention and knowledge in the historical canon) happened in the anarchist territories during the Spanish Revolution.

social revolution

Social revolutions are sudden changes in the structure and nature of society. These revolutions are usually recognized as having transformed society, economy, culture, philosophy, and technology along with but more than just the political syst ...

that began during the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 and resulted in the widespread implementation of anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

and, more broadly, libertarian socialist organizational principles throughout various portions of the country for two to three years, primarily Catalonia, Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to sou ...

, Andalusia, and parts of the Levante. Much of Spain's economy

The economy of Spain is a highly developed social market economy. It is the world's sixteenth-largest by nominal GDP and the sixth-largest in Europe. Spain is a member of the European Union and the eurozone, as well as the Organization for Eco ...

was put under worker control; in anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

strongholds like Catalonia, the figure was as high as 75%, but lower in areas with heavy Communist Party of Spain influence, as the Soviet-allied party actively resisted attempts at collectivization enactment. Factories were run through worker committees, and agrarian areas became collectivized and ran as libertarian communes. Anarchist historian Sam Dolgoff estimated that about eight million people participated directly or at least indirectly in the Spanish Revolution, which he claimed "came closer to realizing the ideal of the free stateless society on a vast scale than any other revolution in history". Stalinist-led troops suppressed the collectives and persecuted both dissident Marxists and anarchists.

Although every sector of the stateless parts of Spain had undergone workers' self-management, collectivization of agricultural and industrial production, and in parts using money or some degree of private property, heavy regulation of markets by democratic communities, other areas throughout Spain used no money at all, and followed principles in accordance with " From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs". One such example was the libertarian communist village of Alcora in the Valencian Community, where money was absent, and the distribution of properties and services was done based upon needs, not who could afford them.

Although every sector of the stateless parts of Spain had undergone workers' self-management, collectivization of agricultural and industrial production, and in parts using money or some degree of private property, heavy regulation of markets by democratic communities, other areas throughout Spain used no money at all, and followed principles in accordance with " From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs". One such example was the libertarian communist village of Alcora in the Valencian Community, where money was absent, and the distribution of properties and services was done based upon needs, not who could afford them.

Post-war years

Anarcho-communism entered into internal debates over the organization issue in the post-World War II era. Founded in October 1935, the Anarcho-Communist Federation of Argentina (FACA, Federación Anarco-Comunista Argentina) in 1955 renamed itself theArgentine Libertarian Federation

The Argentine Libertarian Federation (in Spanish language, Spanish, ''Federación Libertaria Argentina'', FLA) is a libertarianism, libertarian anarchist communism, communist federation which operates in Argentina, out of the Buenos Aires, City o ...

. The Fédération Anarchiste (FA) was founded in Paris on 2 December 1945 and elected the platformist anarcho-communist George Fontenis as its first secretary the following year. It was composed of a majority of activists from the former FA (which supported Volin's Synthesis

Synthesis or synthesize may refer to:

Science Chemistry and biochemistry

*Chemical synthesis, the execution of chemical reactions to form a more complex molecule from chemical precursors

** Organic synthesis, the chemical synthesis of organ ...

) and some members of the former Union Anarchiste, which supported the CNT-FAI support to the Republican government during the Spanish Civil War, as well as some young Resistants. In 1950 a clandestine group formed within the FA called Organisation Pensée Bataille (OPB), led by George Fontenis.Cédric Guérin. "Pensée et action des anarchistes en France : 1950–1970"/ref> The ''Manifesto of Libertarian Communism'' was written in 1953 by Georges Fontenis for the ''Federation Communiste Libertaire'' of France. It is one of the key texts of the anarchist-communist current known as platformism. The OPB pushed for a move that saw the FA change its name to the (FCL) after the 1953 Congress in Paris, while an article in indicated the end of the cooperation with the French Surrealist Group led by

André Breton

André Robert Breton (; 19 February 1896 – 28 September 1966) was a French writer and poet, the co-founder, leader, and principal theorist of surrealism. His writings include the first ''Surrealist Manifesto'' (''Manifeste du surréalisme'') o ...

.

The new decision-making process was founded on unanimity: each person has a right of veto on the orientations of the federation. The FCL published the same year . Several groups quit the FCL in December 1955, disagreeing with the decision to present "revolutionary candidates" to the legislative elections. On 15–20 August 1954, the Ve intercontinental plenum of the CNT took place. A group called appeared, which was formed of militants who did not like the new ideological orientation that the OPB was giving the FCL seeing it was authoritarian and almost Marxist. The FCL lasted until 1956, just after participating in state legislative elections with ten candidates. This move alienated some members of the FCL and thus produced the end of the organization. A group of militants who disagreed with the FA turning into FCL reorganized a new Federation Anarchiste established in December 1953. This included those who formed ''L'Entente anarchiste,'' who joined the new FA and then dissolved L'Entente. The new base principles of the FA were written by the individualist anarchist Charles-Auguste Bontemps

Charles-Auguste Bontemps (February 9, 1893 – October 14, 1981) was a French individualist anarchist, pacifist, freethinker and naturist activist and writer.

Life and works

Bontemps was born on February 9, 1893, in the Nièvre department of Fra ...

and the non-platformist anarcho-communist Maurice Joyeux which established an organization with a plurality of tendencies and autonomy of groups organized around synthesist principles. According to historian Cédric Guérin, "the unconditional rejection of Marxism became from that moment onwards an identity element of the new Federation Anarchiste". This was motivated in a significant part by the previous conflict with George Fontenis and his OPB.

In Italy, the Italian Anarchist Federation The Italian Anarchist Federation ( it, Federazione Anarchica Italiana) is an Italian anarchist federation of autonomous anarchist groups all over Italy. The Italian Anarchist Federation was founded in 1945 in Carrara. It adopted an "Associative Pac ...

was founded in 1945 in Carrara. It adopted an "Associative Pact" and the "Anarchist Program" of Errico Malatesta. It decided to publish the weekly '' Umanità Nova,'' retaking the name of the journal published by Errico Malatesta

Errico Malatesta (4 December 1853 – 22 July 1932) was an Italian anarchist propagandist and revolutionary socialist. He edited several radical newspapers and spent much of his life exiled and imprisoned, having been jailed and expelled from ...

. Inside the FAI, the Anarchist Groups of Proletarian Action (GAAP) was founded, led by Pier Carlo Masini, which "proposed a Libertarian Party with an anarchist theory and practice adapted to the new economic, political and social reality of post-war Italy, with an internationalist outlook and effective presence in the workplaces ..The GAAP allied themselves with the similar development within the French Anarchist movement

Anarchism in France can trace its roots to thinker Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who grew up during the Restoration and was the first self-described anarchist. French anarchists fought in the Spanish Civil War as volunteers in the International Brigad ...

", as led by George Fontenis. Another tendency that did not identify either with the more classical FAI or with the GAAP started to emerge as local groups. These groups emphasized direct action

Direct action originated as a political activist term for economic and political acts in which the actors use their power (e.g. economic or physical) to directly reach certain goals of interest, in contrast to those actions that appeal to oth ...

, informal affinity groups, and expropriation for financing anarchist activity. From within these groups, the influential insurrectionary anarchist

Insurrectionary anarchism is a revolutionary theory and tendency within the anarchist movement that emphasizes insurrection as a revolutionary practice. It is critical of formal organizations such as labor unions and federations that are based o ...

Alfredo Maria Bonanno

Alfredo Maria Bonanno (born 1937 in Catania, Italy) is a main theorist of contemporary insurrectionary anarchism A long-time anarchist, he has been imprisoned multiple times. Bonanno is an editing, editor of ''Anarchismo Editions'' and many othe ...

will emerge influenced by the practice of the Spanish exiled anarchist José Lluis Facerías. In the early seventies, a platformist

Platformism is a form of anarchist organization that seeks unity from its participants, having as a defining characteristic the idea that each platformist organization should include only people that are fully in agreement with core group ideas, r ...

tendency emerged within the Italian Anarchist Federation, which argued for more strategic coherence and social insertion in the workers' movement while rejecting the synthesist "Associative Pact" of Malatesta, which the FAI adhered to. These groups started organizing themselves outside the FAI in organizations such as O.R.A. from Liguria, which organized a Congress attended by 250 delegates of groups from 60 locations. This movement was influential in the movements of the seventies. They published in Bologna and from Modena

Modena (, , ; egl, label=Emilian language#Dialects, Modenese, Mòdna ; ett, Mutna; la, Mutina) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) on the south side of the Po Valley, in the Province of Modena in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern I ...

. The Federation of Anarchist Communists (), or FdCA, was established in 1985 in Italy from the fusion of the (''Revolutionary Anarchist Organisation'') and the ('' Tuscan Union of Anarchist Communists'').

The International of Anarchist Federations (IAF/IFA) was founded during an international anarchist conference in Carrara in 1968 by the three existing European anarchist federations of France (), Italy (), and Spain () as well as the Bulgarian federation in French exile. These organizations were also inspired by synthesist principles.

Contemporary times

'' Libertarian Communism'' was a socialist journal founded in 1974 and partly produced by members of the Socialist Party of Great Britain. Thesynthesist

An analog (or analogue) synthesizer is a synthesizer that uses analog circuits and analog signals to generate sound electronically.

The earliest analog synthesizers in the 1920s and 1930s, such as the Trautonium, were built with a variety of va ...

Italian Anarchist Federation The Italian Anarchist Federation ( it, Federazione Anarchica Italiana) is an Italian anarchist federation of autonomous anarchist groups all over Italy. The Italian Anarchist Federation was founded in 1945 in Carrara. It adopted an "Associative Pac ...

and the platformist

Platformism is a form of anarchist organization that seeks unity from its participants, having as a defining characteristic the idea that each platformist organization should include only people that are fully in agreement with core group ideas, r ...

Federation of Anarchist Communists continue to exist today in Italy, but insurrectionary anarchism continues to be relevant, as the recent establishment of the Informal Anarchist Federation shows.

In the 1970s, the French Fédération Anarchiste evolved into a joining of the principles of synthesis anarchism and platformism. Later the platformist organizations Libertarian Communist Organization (France)

Georges Fontenis (27 April 1920 – 9 August 2010) was a school teacher who worked in Tours. He is more widely remembered on account of his political involvement, especially during the 1950s and 1960s.

A libertarian communist and trades unionist, ...

in 1976 and Alternative libertaire

''Alternative libertaire'' (''AL'', "Libertarian Alternative") was a French anarchist organization formed in 1991 which publishes a monthly magazine, actively participates in a variety of social movements, and is a participant in the Anarkismo.ne ...

in 1991 appeared, with this last one existing until today alongside the synthesist Fédération Anarchiste. Recently, platformist organizations founded the now-defunct International Libertarian Solidarity network and its successor, the Anarkismo network, which is run collaboratively by roughly 30 platformist organizations worldwide.

On the other hand, contemporary insurrectionary anarchism inherits the views and tactics of anti-organizational anarcho-communism and illegalism."Anarchism, insurrections and insurrectionalism" by Joe BlackThe Informal Anarchist Federation (not to be confused with the synthesist Italian Anarchist Federation, also FAI) is an Italian insurrectionary anarchist organization. Italian intelligence sources have described it as a "horizontal" structure of various anarchist terrorist groups, united in their beliefs in revolutionary armed action. In 2003, the group claimed responsibility for a bombing campaign targeting several European Union institutions. Currently, alongside the previously mentioned federations, the International of Anarchist Federations includes the

Argentine Libertarian Federation

The Argentine Libertarian Federation (in Spanish language, Spanish, ''Federación Libertaria Argentina'', FLA) is a libertarianism, libertarian anarchist communism, communist federation which operates in Argentina, out of the Buenos Aires, City o ...

, the Anarchist Federation of Belarus, the Federation of Anarchists in Bulgaria, the Czech-Slovak Anarchist Federation, the Federation of German-speaking Anarchists in Germany and Switzerland, and the Anarchist Federation in the United Kingdom.

Economic theory

The abolition of money, prices, and wage labor are central to anarchist communism. With the distribution of wealth being based on self-determined needs, people would be free to engage in whatever activities they found most fulfilling and would no longer have to engage in work for which they have neither the temperament nor the aptitude. Anarcho-communists argue that there is no good way of measuring the value of any person's economic contributions because all wealth is a common product of current and preceding generations. For instance, one could not measure the value of a factory worker's daily production without considering how transportation, food, water, shelter, relaxation, machine efficiency, emotional mood, etc., contributed to their production. To honestly give numerical economic value to anything, an overwhelming amount of externalities and contributing factors would need to be considered—especially current or past labor contributing to the ability to utilize future labor. As Kropotkin put it: "No distinction can be drawn between the work of each man. Measuring the work by its results leads us to absurdity; dividing and measuring them by hours spent on the work also leads us to absurdity. One thing remains: put the needs above the works, and first of all recognize the right to live, and later on, to the comforts of life, for all those who take their share in production.." Communist anarchism shares many traits with

Communist anarchism shares many traits with collectivist anarchism

Collectivist anarchism, also called anarchist collectivism and anarcho-collectivism, Buckley, A. M. (2011). ''Anarchism''. Essential Libraryp. 97 "Collectivist anarchism, also called anarcho-collectivism, arose after mutualism." . is an anarchis ...

, but the two are distinct. Collectivist anarchism believes in collective ownership, while communist anarchism negates the entire concept of ownership in favor of the concept of usage. Crucially, the abstract relationship of "landlord" and "tenant" would no longer exist, as such titles are held to occur under conditional legal coercion and are not necessary to occupy buildings or spaces ( intellectual property rights would also cease since they are a form of private property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property and personal property, which is owned by a state entity, and from collective or ...

). In addition to believing rent and other fees are exploitative, anarcho-communists feel these are arbitrary pressures inducing people to carry out unrelated functions. For example, they question why one should have to work for 'X hours' a day to merely live somewhere. So instead of working conditionally for the wage earned, they believe in working directly for the objective.

Gift economies and commons-based organizing

In anthropology and the social sciences, a gift economy (or gift culture) is a mode of exchange where valuable goods and services are regularly given without explicit agreement for immediate or future rewards (i.e., no formal ''

In anthropology and the social sciences, a gift economy (or gift culture) is a mode of exchange where valuable goods and services are regularly given without explicit agreement for immediate or future rewards (i.e., no formal ''quid pro quo

Quid pro quo ('what for what' in Latin) is a Latin phrase used in English to mean an exchange of goods or services, in which one transfer is contingent upon the other; "a favor for a favor". Phrases with similar meanings include: "give and take", ...

'' exists). Ideally, voluntary and recurring gift exchange circulates and redistributes wealth throughout a community and serves to build societal ties and obligations. In contrast to a barter or market economy

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand, where all suppliers and consumers ...

, social norms and customs govern gift exchange rather than an explicit exchange of goods or services for money or some other commodity

In economics, a commodity is an economic good, usually a resource, that has full or substantial fungibility: that is, the market treats instances of the good as equivalent or nearly so with no regard to who produced them.

The price of a comm ...

.

Traditional societies dominated by gift exchange were small in scale and geographically remote from each other. Market exchange dominated as states formed to regulate trade and commerce within their boundaries. Nonetheless, gift exchange continues to play an essential role in modern society. One prominent example is scientific research, which can be described as a gift economy. Contrary to popular conception, there is no evidence that societies relied only on barter before using money for trade. Instead, non-monetary societies operated primarily along the principles of gift economics, and in more complex economies, on debt. When barter occurred, it was usually between strangers or would-be enemies.

The expansion of the Internet has witnessed a resurgence of the gift economy, especially in the technology sector. Engineers, scientists, and software developers create open-source software projects. The Linux kernel

The Linux kernel is a free and open-source, monolithic, modular, multitasking, Unix-like operating system kernel. It was originally authored in 1991 by Linus Torvalds for his i386-based PC, and it was soon adopted as the kernel for the GNU ope ...

and the GNU operating system are prototypical examples of the gift economy's prominence in the technology sector and its active role in using permissive free software and copyleft licenses, which allow free reuse of software and knowledge. Other examples include file-sharing, the commons, and open access

Open access (OA) is a set of principles and a range of practices through which research outputs are distributed online, free of access charges or other barriers. With open access strictly defined (according to the 2001 definition), or libre op ...

. Anarchist scholar Uri Gordon has argued:

The interest in such economic forms goes back to Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activis ...

, who saw in the hunter-gatherer tribes he had visited the paradigm of " mutual aid".'' Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution'' (1955 paperback (reprinted 2005), includes Kropotkin's 1914 preface, Foreword and Bibliography by Ashley Montagu, and The Struggle for Existence, by Thomas H. Huxley