Anarchism in Vietnam on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anarchism in Vietnam first emerged in the early twentieth century, as Vietnamese radicals such as

Anarchism was first introduced to the Vietnamese anti-colonial movement during the 1900s, by the early nationalist leader

Anarchism was first introduced to the Vietnamese anti-colonial movement during the 1900s, by the early nationalist leader  As more Vietnamese expatriates joined up with internationalist organizations in China, they increasingly came into contact with anarchist individuals and groups. Phan Bội Châu himself, who had developed ties with the Tokyo strand of Chinese anarchism led by Zhang Binglin and Liu Shipei, was inspired by their traditionalist approach to anarchism and socialism. Phan was particularly inspired by the anarchist positions on

As more Vietnamese expatriates joined up with internationalist organizations in China, they increasingly came into contact with anarchist individuals and groups. Phan Bội Châu himself, who had developed ties with the Tokyo strand of Chinese anarchism led by Zhang Binglin and Liu Shipei, was inspired by their traditionalist approach to anarchism and socialism. Phan was particularly inspired by the anarchist positions on

By this time, Phan Bội Châu's political influence was largely marginalized and his followers in the Restoration League began to leave him behind. Despite attempts to keep the League alive, its prominent members started to criticize it for its

By this time, Phan Bội Châu's political influence was largely marginalized and his followers in the Restoration League began to leave him behind. Despite attempts to keep the League alive, its prominent members started to criticize it for its

Despite these challenges from the emerging communist movement,

Despite these challenges from the emerging communist movement,

Upon his release from prison in October 1931, Nguyễn An Ninh returned to his organizing work in the countryside. Ninh served as a unifying non-partisan presence for anti-colonial elements to join together in a

Upon his release from prison in October 1931, Nguyễn An Ninh returned to his organizing work in the countryside. Ninh served as a unifying non-partisan presence for anti-colonial elements to join together in a  In the Cochinchinese parliamentary election of March 1935, the '' La Lutte'' group received 17% of the vote, although they failed to win a seat. There was also a ''La Lutte'' candidacy that ran in the May 1935 Saigon municipal election, in which four members of the alliance were elected, but three were invalidated due to their communist sympathies. The alliance also went on to organize a number of strikes in the subsequent years.

However, the united front was soon brought to an end in 1936, when the newly elected

In the Cochinchinese parliamentary election of March 1935, the '' La Lutte'' group received 17% of the vote, although they failed to win a seat. There was also a ''La Lutte'' candidacy that ran in the May 1935 Saigon municipal election, in which four members of the alliance were elected, but three were invalidated due to their communist sympathies. The alliance also went on to organize a number of strikes in the subsequent years.

However, the united front was soon brought to an end in 1936, when the newly elected

With the defeat and dissolution of the

With the defeat and dissolution of the

Phan Bội Châu

Phan Bội Châu (; 26 December 1867 – 29 October 1940), born Phan Văn San, courtesy name Hải Thụ (later changed to Sào Nam), was a pioneer of Vietnamese 20th century nationalism. In 1903, he formed a revolutionary organization called ' ...

and Nguyễn An Ninh

Nguyễn An Ninh (September 5, 1900 – August 14, 1943) was a radical Vietnamese political journalist and publicist in French colonial Cochinchina (southern Vietnam). An independent and charismatic figure, Nguyen An Ninh was able to conciliate ...

became exposed to strands of anarchism in Japan, China and France. The spread of anarchism through Vietnam was responsible for an increase in violence against the colonial authorities, inspired by the principle of propaganda of the deed

Propaganda of the deed (or propaganda by the deed, from the French ) is specific political direct action meant to be exemplary to others and serve as a catalyst for revolution.

It is primarily associated with acts of violence perpetrated by pro ...

, but it also brought humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humani ...

to revolutionary circles of its time. Anarchism reached its apex in Vietnam during the 1920s, but it soon began to lose its influence with the introduction of Marxism-Leninism and the beginning of the Vietnamese communist movement.

History

The roots of anarchism in Vietnam lay in the early resistance to French colonial rule, organized among various secret societies. Among these were theHeaven and Earth Society

The Tiandihui, the Heaven and Earth Society, also called Hongmen (the Vast Family), is a Chinese fraternal organization and historically a secretive folk religious sect in the vein of the Ming loyalist White Lotus Sect, the Tiandihui's ...

, which in 1884 had assassinated a colonial collaborator in Saigon. Other attacks against the French colonial authorities included the Cần Vương movement

The Cần Vương (, Hán tự: , ) movement was a large-scale Vietnamese insurgency between 1885 and 1889 against French colonial rule. Its objective was to expel the French and install the Hàm Nghi Emperor as the leader of an independent Vi ...

, which attempted to overthrow the French during the late 1880s, the Hanoi Poison Plot

The Poisoning at Hanoi Citadel (Vietnamese:''Hà Thành đầu độc'') was a poisoning plot which occurred in 1908 when a group of Vietnamese indigenous tirailleurs attempted to poison the entire French colonial army's garrison in the Citadel ...

, in which indigenous Vietnamese troops attempted to assassinate the entire French garrison in the Citadel of Hanoi

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

I ...

, as well as subsequent anti-colonial uprisings in Cochinchina

Cochinchina or Cochin-China (, ; vi, Đàng Trong (17th century - 18th century, Việt Nam (1802-1831), Đại Nam (1831-1862), Nam Kỳ (1862-1945); km, កូសាំងស៊ីន, Kosăngsin; french: Cochinchine; ) is a historical exony ...

and Tonkin

Tonkin, also spelled ''Tongkin'', ''Tonquin'' or ''Tongking'', is an exonym referring to the northern region of Vietnam. During the 17th and 18th centuries, this term referred to the domain ''Đàng Ngoài'' under Trịnh lords' control, includi ...

.

Official French colonial publications implied that these Vietnamese secret societies and religious sects could be easily coopted by revolutionaries, due to their status as indigenous methods of organizing, echoing Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary ...

's claim that social bandits

Social banditry or social crime is a form of lower class social resistance involving behavior that by law is illegal but is supported by wider "oppressed" society as being moral and acceptable. The term ''social bandit'' was invented by the Mar ...

were "instinctive revolutionaries".

International origins

Anarchism was first introduced to the Vietnamese anti-colonial movement during the 1900s, by the early nationalist leader

Anarchism was first introduced to the Vietnamese anti-colonial movement during the 1900s, by the early nationalist leader Phan Bội Châu

Phan Bội Châu (; 26 December 1867 – 29 October 1940), born Phan Văn San, courtesy name Hải Thụ (later changed to Sào Nam), was a pioneer of Vietnamese 20th century nationalism. In 1903, he formed a revolutionary organization called ' ...

. In January 1905, Phan moved to Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

, where he was exposed to a variety of new political ideas being propagated among Chinese expatriates, including the constitutionalism

Constitutionalism is "a compound of ideas, attitudes, and patterns of behavior elaborating the principle that the authority of government derives from and is limited by a body of fundamental law".

Political organizations are constitutional ...

of Liang Qichao

Liang Qichao (Chinese: 梁啓超 ; Wade–Giles, Wade-Giles: ''Liang2 Chʻi3-chʻao1''; Yale romanization of Cantonese, Yale: ''Lèuhng Kái-chīu'') (February 23, 1873 – January 19, 1929) was a Chinese politician, social and political act ...

, the republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

of the Tongmenghui

The Tongmenghui of China (or T'ung-meng Hui, variously translated as Chinese United League, United League, Chinese Revolutionary Alliance, Chinese Alliance, United Allegiance Society, ) was a secret society and underground resistance movement ...

, and the anarchism of the Tokyo group. Initially a utilitarian

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charac ...

, Phan began to rapidly move through a variety of political ideologies and made acquaintance with a number of politically diverse groups and individuals in Japan. In 1907, Phan founded the Constitutionalist Association ( vi, Cong Hien Hoi), an organization of Vietnamese expatriate students which advocated for constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

, but by 1908 it was forcibly disbanded by the Japanese authorities, at the request of the French. That same year, Phan joined the Asian Friendship Association, an organization founded by the exiled Chinese republicans and anarchists, as well as Japanese socialists

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspo ...

. The Association was largely directed by Liu Shipei

Liu Shipei (; 24 June 1884 – 20 December 1919) was a philologist, Chinese anarchist, and revolutionary activist. While he and his wife, He Zhen were in exile in Japan he became a fervent nationalist. He then saw the doctrines of anarchism a ...

, a prominent member of the Tokyo anarchist group and editor of its newspaper ''Natural Justice'', and included many other Chinese anarchists such as Chang Chi, who was a close friend of Phan's.

But by 1909, Phan Bội Châu was ordered to leave Japan and spent the subsequent years drifting around East Asia. After the overthrow of the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

during the 1911 revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China. The revolution was the culmination of a d ...

, Phan was invited to the newly established Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

by his old Chinese republican friends from Japan, Zhang Binglin

Zhang Binglin (January 12, 1869 – June 14, 1936), also known by his art name Zhang Taiyan, was a Chinese philologist, textual critic, philosopher, and revolutionary.

His philological works include ''Wen Shi'' (文始 "The Origin of Writing"), t ...

and Chen Qimei

Chen Qimei (; 17 January 1878 – 18 May 1916), courtesy name Yingshi (英世) was a Chinese revolutionary activist and key figure of Green Gang, close political ally of Sun Yat-sen, and early mentor of Chiang Kai-shek. He was as one of the found ...

. In January 1912, Phan arrived in China and settled in Guangdong

Guangdong (, ), alternatively romanized as Canton or Kwangtung, is a coastal province in South China on the north shore of the South China Sea. The capital of the province is Guangzhou. With a population of 126.01 million (as of 2020) ...

, now under the governorship of his friend Hu Hanmin

Hu Hanmin (; born in Panyu, Guangdong, Qing dynasty, China, 9 December 1879 – Kwangtung, Republic of China, 12 May 1936) was a Chinese philosopher and politician who was one of the early conservative right factional leaders in the Kuomintang ...

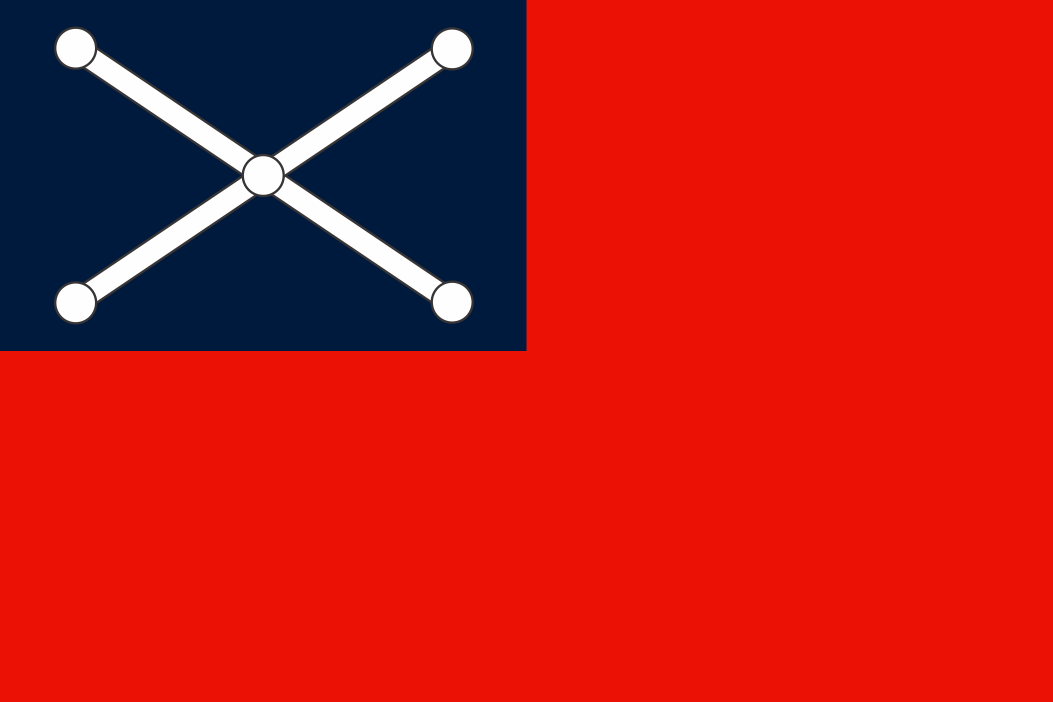

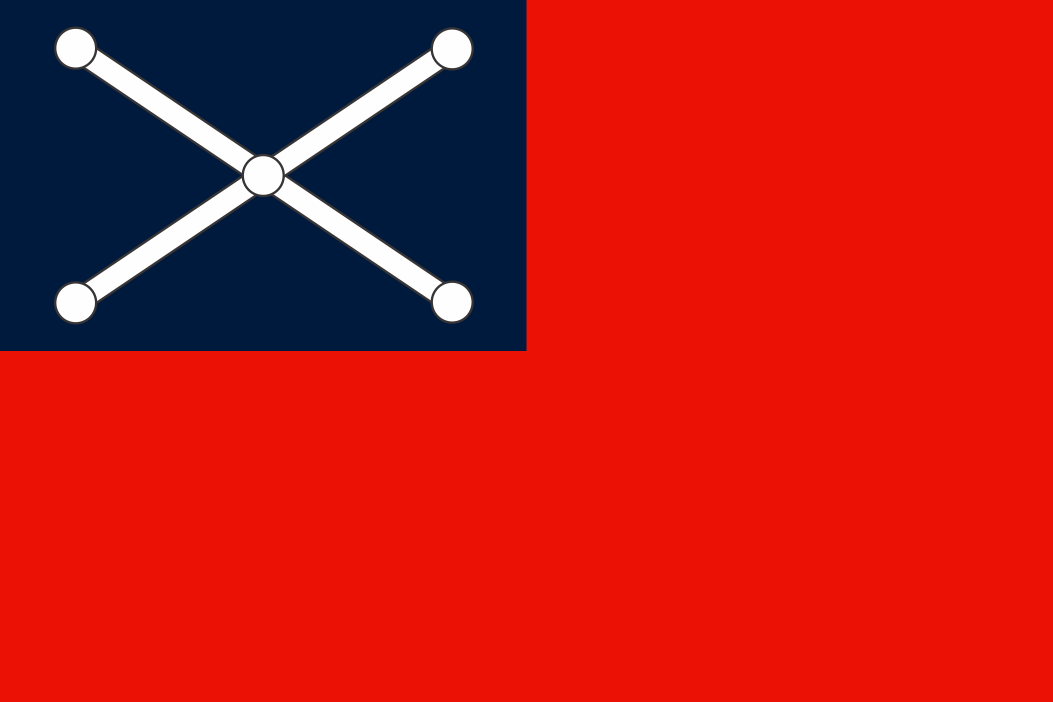

, who was actively providing a place of refuge for Vietnamese exiles. Here, with the financial aid of the Guangzhou anarchist Liu Shifu

Liu Shifu (; born Liu Shaobin; 27 June 1884 – 27 March 1915) also known as Sifu, was an Esperantist and an influential figure in the Chinese revolutionary movement in the early twentieth century, and in the Chinese anarchist movement in partic ...

, Phan formed a new republican and nationalist organization called the Vietnamese Restoration League ( vi, Việt Nam Quang Phục Hội), modeled after Sun Yat-Sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

's Tongmenghui

The Tongmenghui of China (or T'ung-meng Hui, variously translated as Chinese United League, United League, Chinese Revolutionary Alliance, Chinese Alliance, United Allegiance Society, ) was a secret society and underground resistance movement ...

and drawing its name from Zhang Binglin's Restoration Society. Shifu also encouraged Phan to establish the Association for the Revitalization of China, an organization dedicated to soliciting Chinese support for the independence movements in colonized Asian countries, including Indochina

Mainland Southeast Asia, also known as the Indochinese Peninsula or Indochina, is the continental portion of Southeast Asia. It lies east of the Indian subcontinent and south of Mainland China and is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the west an ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

and Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

. Upon moving to Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flow ...

, Phan joined the Worldwide League for Humanity, a clandestine anarchist organization which went unrecognized by the new Beiyang government

The Beiyang government (), officially the Republic of China (), sometimes spelled Peiyang Government, refers to the government of the Republic of China which sat in its capital Peking (Beijing) between 1912 and 1928. It was internationally r ...

due to its "extreme-left program."

As more Vietnamese expatriates joined up with internationalist organizations in China, they increasingly came into contact with anarchist individuals and groups. Phan Bội Châu himself, who had developed ties with the Tokyo strand of Chinese anarchism led by Zhang Binglin and Liu Shipei, was inspired by their traditionalist approach to anarchism and socialism. Phan was particularly inspired by the anarchist positions on

As more Vietnamese expatriates joined up with internationalist organizations in China, they increasingly came into contact with anarchist individuals and groups. Phan Bội Châu himself, who had developed ties with the Tokyo strand of Chinese anarchism led by Zhang Binglin and Liu Shipei, was inspired by their traditionalist approach to anarchism and socialism. Phan was particularly inspired by the anarchist positions on anti-imperialism

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is a term used in a variety of contexts, usually by nationalist movements who want to secede from a larger polity (usually in the form of an empire, but also in a multi-ethnic so ...

and direct action

Direct action originated as a political activist term for economic and political acts in which the actors use their power (e.g. economic or physical) to directly reach certain goals of interest, in contrast to those actions that appeal to oth ...

, leading him to defend the violent overthrow of the French colonial authorities, even to the chagrin of his republican allies like Hu Hanmin and Chen Qimei. Developing on propaganda of the deed

Propaganda of the deed (or propaganda by the deed, from the French ) is specific political direct action meant to be exemplary to others and serve as a catalyst for revolution.

It is primarily associated with acts of violence perpetrated by pro ...

, Phan admired past assassination attempts against state officials and encouraged the targeting of French colonial officials, leading to a series of bombings in Hanoi

Hanoi or Ha Noi ( or ; vi, Hà Nội ) is the capital and second-largest city of Vietnam. It covers an area of . It consists of 12 urban districts, one district-leveled town and 17 rural districts. Located within the Red River Delta, Hanoi is ...

, which brought both increased publicity and reprisals against the Restoration League. Several of the League's activists were executed, internationalist organizations in China began to disintegrate and Phan himself was arrested and imprisoned by the Beiyang government. While Phan was in prison, Liu Shipei died of tuberculosis in 1915, Chen Qimei was assassinated in 1916 and Zhang Binglin abandoned anarchism and gave up on political pursuits, leaving Phan politically isolated by the time of his release in February 1917. After briefly coming under the influence of a collaborationist advocate, Phan turned his interests towards socialism, inspired by the socialist currents of the Russian and Chinese revolutions.

Following the end of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, many more Vietnamese radicals went into exile, looking for knowledge that was being suppressed in French Indochina. People from Annam and Tonkin

Tonkin, also spelled ''Tongkin'', ''Tonquin'' or ''Tongking'', is an exonym referring to the northern region of Vietnam. During the 17th and 18th centuries, this term referred to the domain ''Đàng Ngoài'' under Trịnh lords' control, includi ...

largely went to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

or Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

, where they were exposed to social anarchist

Social anarchism is the branch of anarchism that sees individual freedom as interrelated with mutual aid.Suissa, Judith (2001). "Anarchism, Utopias and Philosophy of Education". ''Journal of Philosophy of Education'' 35 (4). pp. 627–646. . ...

tendencies, whilst those from Cochinchina

Cochinchina or Cochin-China (, ; vi, Đàng Trong (17th century - 18th century, Việt Nam (1802-1831), Đại Nam (1831-1862), Nam Kỳ (1862-1945); km, កូសាំងស៊ីន, Kosăngsin; french: Cochinchine; ) is a historical exony ...

went to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, where they became influenced by French strands of individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism is the branch of anarchism that emphasizes the individual and their Will (philosophy), will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions and ideological systems."What do I mean by individualism? I mean ...

. While Vietnamese expatriates that took up the Chinese strand of anarchism tended to employ aspects of traditionalism, expatriates inspired by French anarchism employed a more radical, youth-oriented and forward-looking philosophy.

Growth and spread of anarchism

This diversity of opinion among Vietnamese anarchists was reflected upon the exiles' return to Vietnam. Political opposition was harshly repressed in the northern colonies of Annam and Tonkin, the anti-colonial movement turned to illegal activism and violent actions against colonial authorities. This, combined with the social anarchism brought back from abroad, laid the groundwork for the formation of political organizations. But in the southern colony of Cochinchina,freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic News media, media, especially publication, published materials, should be conside ...

existed, allowing Vietnamese radicals to participate in open political discourse, which defused political tensions. Upon his return from France, the individualist anarchist Nguyễn An Ninh

Nguyễn An Ninh (September 5, 1900 – August 14, 1943) was a radical Vietnamese political journalist and publicist in French colonial Cochinchina (southern Vietnam). An independent and charismatic figure, Nguyen An Ninh was able to conciliate ...

found a place in radical journalism, publishing political tracts in his journal ''La Cloche Fêlée'' which encouraged the synthesis of the social struggle for individual liberties with the national struggle for Vietnamese independence. Ninh called for the youth of Vietnam to reinvent itself and take control of its own destiny, becoming incredibly popular amongst his peers, as his rhetorical tone marked a stark contrast to the tendency towards moderation and compromise. Ninh critiqued the Confucian family values of parental authority and gender inequality, as well as traditional morality, encouraging people to "break with the past and free themselves from tyranny of all kinds" and create a genuinely new culture. He also attacked the bureaucratism of the colonial state, the native Vietnamese bourgeoisie and traditional Confucian society. Ninh explicitly expounded his anarchist views in his article ''Order and Anarchy'', quoting such authors as Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore (; bn, রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর; 7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was a Bengali polymath who worked as a poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer and painter. He resh ...

and Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

. Ninh's anti-authoritarianism also extended into his personal life, as he got himself into a number of conflicts with colonial officials. In addition, while Ninh admired the Soviet Union, he positioned himself firmly against a Bolshevik-style revolution due to its human cost, preferring the route of individuals directly undermining social inequalities rather than partaking in revolutionary violence. However, as time passed, Ninh increasingly saw revolution as inevitable and began to agitate for organized resistance to achieve social justice.

By this time, Phan Bội Châu's political influence was largely marginalized and his followers in the Restoration League began to leave him behind. Despite attempts to keep the League alive, its prominent members started to criticize it for its

By this time, Phan Bội Châu's political influence was largely marginalized and his followers in the Restoration League began to leave him behind. Despite attempts to keep the League alive, its prominent members started to criticize it for its elitism

Elitism is the belief or notion that individuals who form an elite—a select group of people perceived as having an intrinsic quality, high intellect, wealth, power, notability, special skills, or experience—are more likely to be constructi ...

and called for Vietnamese revolutionaries to immerse themselves among the common people. In 1923, the Society of Like Hearts ( vi, Tam Tam Xa emerged from these critical anarchist currents of the revolutionary movement, inspired in particular by the works of Liu Shifu, and attempted to unite disparate Vietnamese anti-colonial activists around collective decision-making. The Society also employed the use of direct action to destabilize the colonial administration, with Phạm Hồng Thái launching an assassination attempt against Governor-General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

Martial Henri Merlin. Although the attempt itself failed, it reinvigorated the Vietnamese anti-colonial movement and Thái became known as a revolutionary martyr. In response, Phan Bội Châu attempted to open a military academy to train Vietnamese revolutionaries, meeting with the anarchist elder Cai Yuanpei

Cai Yuanpei (; 1868–1940) was a Chinese philosopher and politician who was an influential figure in the history of Chinese modern education. He made contributions to education reform with his own education ideology. He was the president of Pek ...

and agents of the Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by a ...

to discuss this project, but it ultimately did not materialize. With the Restoration League failing to reform itself along the lines of the Chinese Nationalist Party

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Taiw ...

and the Society of Hearts unable to successfully follow the assassination attempt, both organizations began to decline into irrelevance. Following a reorganization in 1924, the Phuc Viet party attempted to mobilize public opinion towards anti-colonialism, with Ton Quang Phiet writing the article ''Southern Wind'', highlighting the need for organization. However, none of these anarchist organizations had presented a clear vision of a future society and had not developed a solid analysis of the present society, thus were left without a strong ideological foundation to unite behind. In 1925, French agents seized Phan Bội Châu in Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flow ...

. He was convicted of treason and spent the rest of his life under house arrest in Huế

Huế () is the capital of Thừa Thiên Huế province in central Vietnam and was the capital of Đàng Trong from 1738 to 1775 and of Vietnam during the Nguyễn dynasty from 1802 to 1945. The city served as the old Imperial City and admi ...

. On March 21, 1926, Nguyễn An Ninh was also arrested and only days later, Phan Chu Trinh

Phan Châu Trinh (Chữ Hán: 潘周楨, 9 September 1872 – 24 March 1926), courtesy name Tử Cán (梓幹), pen name Tây Hồ (西湖) or Hi Mã (希馬), was an early 20th-century Vietnamese nationalist. He sought to end France's colonial oc ...

died, causing mass protests against the government in April 1926. It was in this atmosphere that a young Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

called Nguyễn Ái Quốc

(: ; born ; 19 May 1890 – 2 September 1969), commonly known as ('Uncle Hồ'), also known as ('President Hồ'), ('Father of the Nation, Old father of the people') and by other Pseudonym, aliases, was a Vietnamese people, Vietnam ...

emerged onto the scene, having links to both strands of Vietnamese anarchism and taking on a role as a fierce critic of radicalism.

Revolutionary socialism and anarchist populism

The first instance of the word "revolution" being introduced to Vietnam was through the writings ofLiang Qichao

Liang Qichao (Chinese: 梁啓超 ; Wade–Giles, Wade-Giles: ''Liang2 Chʻi3-chʻao1''; Yale romanization of Cantonese, Yale: ''Lèuhng Kái-chīu'') (February 23, 1873 – January 19, 1929) was a Chinese politician, social and political act ...

, in the midst of the New Culture Movement

The New Culture Movement () was a movement in China in the 1910s and 1920s that criticized classical Chinese ideas and promoted a new Chinese culture based upon progressive, modern and western ideals like democracy and science. Arising out of ...

, Qichao advocated for a widespread cultural revolution, rather than a violent political revolution. The definition of "revolution" that was adopted in Vietnam meant "changing the Mandate of Heaven

The Mandate of Heaven () is a Chinese political philosophy that was used in ancient and imperial China to legitimize the rule of the King or Emperor of China. According to this doctrine, heaven (天, ''Tian'') – which embodies the natural ...

" ( vi, cách mạng), which was interpreted in many different ways. One of the first such revolutionary tracts was Nguyễn Thượng Hiền

Nguyễn Thượng Hiền (wikt:阮, 阮wikt:尚, 尚wikt:賢, 賢; 1865–1925) was a Vietnamese scholar-gentry anti-colonial revolutionary activist who advocated independence from French Indochina, French colonial rule. He was a contemporary ...

's ''On Revolution'', published on January 3, 1925, in which he called for a peaceful boycott movement, inspired by the Swadeshi movement

The Swadeshi movement was a self-sufficiency movement that was part of the Indian independence movement and contributed to the development of Indian nationalism. Before the BML Government's decision for the partition of Bengal was made public in ...

organized by Mohandas K. Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, but in which he also failed to define the means nor the ends of a revolution in Vietnam. The restriction of the distribution of French language literature, such as documents of the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

or Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

, meant that only French-educated urban elements were exposed to them, which reinforced the elitist tendencies that pervaded Vietnamese radicalism and ensured the continuation of the idea that the revolution was a top-down affair organized by intellectuals, rather than a mass uprising.

Revolutionary socialist

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revoluti ...

ideas began to work their way into Vietnam through the writings of Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

, which advocated for a tightly-organized opposition movement, guided by educated Marxist intellectuals. Although socialism and anarchism had previously been expounded as one and the same, Vietnamese revolutionaries now found themselves forced to choose between the two tendencies, which were becoming more antagonistic towards each other. The rise of communism in China and France provided considerably more exposure to pro-Bolshevik currents which, combined with the fallout from the suppression of the Kronstadt Rebellion

The Kronstadt rebellion ( rus, Кронштадтское восстание, Kronshtadtskoye vosstaniye) was a 1921 insurrection of Soviet sailors and civilians against the Bolshevik government in the Russian SFSR port city of Kronstadt. Locat ...

, increased hostility towards anarchist ideas.

Nguyễn Ái Quốc

(: ; born ; 19 May 1890 – 2 September 1969), commonly known as ('Uncle Hồ'), also known as ('President Hồ'), ('Father of the Nation, Old father of the people') and by other Pseudonym, aliases, was a Vietnamese people, Vietnam ...

solicited aid from the Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by a ...

for support in the Vietnamese anti-colonial struggle, but himself was skeptical of forming an openly communist movement in the country, due to what he saw as a "political naiveté" among Vietnamese radicals. He particularly criticized Nguyễn Thượng Hiền's work, insisting on a particular need to reject reformism

Reformism is a political doctrine advocating the reform of an existing system or institution instead of its abolition and replacement.

Within the socialist movement, reformism is the view that gradual changes through existing institutions can eve ...

and evolutionary change in favor of a political revolution, and further critiqued the use of non-violent boycott movements. In early 1925, Quốc established the Vietnamese Revolutionary Youth League Vietnamese Revolutionary Youth League (; Chữ Nôm: ''越南青年革命同志会''), or Thanh Niên for short, was founded by Nguyen Ai Quoc (best known as Ho Chi Minh) in Guangzhou in the spring of 1925. It is considered as the “first truly Mar ...

to organize young Vietnamese people towards collective action. Anarchism, as championed by Nguyễn An Ninh

Nguyễn An Ninh (September 5, 1900 – August 14, 1943) was a radical Vietnamese political journalist and publicist in French colonial Cochinchina (southern Vietnam). An independent and charismatic figure, Nguyen An Ninh was able to conciliate ...

, still presented a significant challenge to Quốc's nascent communist movement, as it appealed to the same young people that the communists were trying to recruit. Quốc himself presented a fierce criticism of anarchism:

Quốc also critiqued the anarcho-communism

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains resp ...

proposed by Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activis ...

, taking the Orthodox Marxist line that the state could only wither away after wealth was redistributed and the people reeducated. Although he admired the ideal of creating a post-revolutionary society without laws, he concluded that anarchist theories would only serve to "sow disorder in society", particularly attempting to refute the anarchist critique of political parties, which presented the greatest challenge to his own ambitions.

Despite these challenges from the emerging communist movement,

Despite these challenges from the emerging communist movement, Nguyễn An Ninh

Nguyễn An Ninh (September 5, 1900 – August 14, 1943) was a radical Vietnamese political journalist and publicist in French colonial Cochinchina (southern Vietnam). An independent and charismatic figure, Nguyen An Ninh was able to conciliate ...

set about building a revolutionary populist movement to advance the anarchist cause, establishing the ''Nguyen An Ninh Secret Society''. Ninh's envisaged a revolutionary vanguard in contrast to the political party system advanced by Leninism, instead advocating for it to be a loose movement that resulted from the moral and intellectual transformation of individuals. He sharply criticized the authoritarianism

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political '' status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic vot ...

of political parties that sought power, while also growing more hostile to the bourgeoisie. Instead of party politics, he saw the path to an anti-authoritarian liberation movement lay in anarchist populism, embracing the concept of revolutionary spontaneity

Revolutionary spontaneity, also known as spontaneism, is a revolutionary socialist tendency that believes the social revolution can and should occur spontaneously from below by the working class itself, without the aid or guidance of a vanguar ...

. Ninh also followed the Bakuninist school of thought regarding the revolutionary potential of the lumpenproletariat

In Marxist theory, the ''Lumpenproletariat'' () is the underclass devoid of class consciousness. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels coined the word in the 1840s and used it to refer to the unthinking lower strata of society exploited by reactionary a ...

, a class that was largely neglected by Orthodox Marxists, and sought to organise the Vietnamese underclasses. Ninh's revolutionary populism began to rapidly spread through Hóc Môn

Hóc Môn is a township () and capital of Hóc Môn District, Ho Chi Minh City

, population_density_km2 = 4,292

, population_density_metro_km2 = 697.2

, population_demonym = Saigonese

, blank_name = GRP (Nominal)

, b ...

, his home district of Saigon

, population_density_km2 = 4,292

, population_density_metro_km2 = 697.2

, population_demonym = Saigonese

, blank_name = GRP (Nominal)

, blank_info = 2019

, blank1_name = – Total

, blank1_ ...

. Following Ninh's release from prison, he began to actively agitate among workers and peasants in and around Saigon, travelling from place to place by bicycle with the aid of local monks and peasants. By March 1928, the existence of Ninh's Secret Society was discovered by the ''Sûreté

(; , but usually translated as afety" or "security)"Security" in French is ''sécurité''. The ''sûreté'' was originally called ''Brigade de Sûreté'' ("Surety Brigade"). is, in many French-speaking countries or regions, the organizational ...

'', known publicly as the Aspirations of Youth Party. The Society recruited people into its mutual friendship and mutual aid associations while also, according to the ''Sûreté'', establishing militia structures organized by local villages. Although the organizational structure of the Secret Society was very loose-knit, Ninh's associates managed to recruit up to 800 members from the workers and peasants of Saigon. Ninh eventually proposed that the Society merge with a number of revolutionary political parties. The Revolutionary Party of New Vietnam turned down the proposal, preferring to retain a small and ideologically homogenous membership, despite the potential offered by the Society's much larger size. The Nationalist Party of Vietnam also rejected this proposal, as it was turned off by the extremism of Ninh's anarcho-populist politics.

On September 28, 1928, Nguyễn An Ninh and his associate Phan Văn Hùm Phan Văn Hùm (9 April 1902 – 1946) was a Vietnamese journalist, philosopher and revolutionary in French colonial Cochinchina who, from 1930, participated in the Trotskyist left opposition to the Communist Party of Nguyen Ai Quoc (Ho Chi Minh).

...

were arrested after an altercation with the police and given prison sentences. The ''Sûreté'' subsequently exposed Ninh's Secret Society and detained 500 of his followers, with 115 standing trial over the following year. While Ninh was in prison, some activists managed to keep the Society going, but when a series of uprisings, strikes and demonstrations broke out in 1930, many of Ninh's followers were led to the newly established Indochinese Communist Party

The Indochinese Communist Party (ICP), km, បក្សកុម្មុយនីស្តឥណ្ឌូចិន, lo, ອິນດູຈີນພັກກອມມູນິດ, zh, t=印度支那共產黨 was a political party which was t ...

.

''La Lutte'' and the United Front

Upon his release from prison in October 1931, Nguyễn An Ninh returned to his organizing work in the countryside. Ninh served as a unifying non-partisan presence for anti-colonial elements to join together in a

Upon his release from prison in October 1931, Nguyễn An Ninh returned to his organizing work in the countryside. Ninh served as a unifying non-partisan presence for anti-colonial elements to join together in a united front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts and/or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political a ...

and legally oppose the government in the Saigon municipal elections of 1933, uniting members of the Communist Party with nationalists, Trotskyists and anarchists. They rallied support through the publication of the newspaper '' La Lutte'' and succeeded in electing two members of the alliance to the Saigon city council. In October 1934, Ninh revived the ''La Lutte'' collaboration to run various campaigns and participate in elections, "focused squarely on the plight of the urban poor, the workers and peasant labourers."

Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

government failed to deliver on its promises of colonial reform. The Trotskyists led by Tạ Thu Thâu

Tạ Thu Thâu (1906–1945) in the 1930s was the principal representative of Trotskyism in Vietnam and, in colonial Cochinchina, of left opposition to the Indochinese Communist Party (PCI) of Nguyen Ai Quoc (Ho Chi Minh). He joined to Left Oppos ...

, who took an oppositionist stance towards the new French government, soon became the dominant tendency within ''La Lutte'', leading the Communist Party to split off from the alliance in 1937, launching their own newspaper and publishing attacks against the Trotskyists. In the 1939 Cochinchinese parliamentary election Colonial Council elections were held in French Cochinchina on 16 April 1939.

Electoral system

The 24 members of the Colonial Council consisted of ten members elected by French citizens, ten by Vietnamese who were classed as French subjects, two by ...

, the Trotskyists of ''La Lutte'' and the Communist Party ran on different lists. The Trotskyist "Workers' and Peasants' Slate" were victorious, electing three candidates with around 80% of the vote, whereas the Communist-backed "Democratic Front", which included Nguyễn An Ninh himself, was defeated with only 1% of the vote.

Following the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

and the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the amicable relations between France and the Soviet Union were severed, leading France to undertake a repression of any seditious factions in Vietnam - sentencing Nguyễn An Ninh to 5 years in Côn Đảo Prison

Côn Đảo Prison ( vi, Nhà tù Côn Đảo), also Côn Sơn Prison, is a prison on Côn Sơn Island (also known as Côn Lôn) the largest island of the Côn Đảo archipelago in southern Vietnam (today it is in Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu provi ...

. During the war, Phan Bội Châu

Phan Bội Châu (; 26 December 1867 – 29 October 1940), born Phan Văn San, courtesy name Hải Thụ (later changed to Sào Nam), was a pioneer of Vietnamese 20th century nationalism. In 1903, he formed a revolutionary organization called ' ...

and Nguyễn An Ninh both died in captivity, bringing a definitive end to the leadership of anarchism in Vietnam.

Revolution and exiled radicalism

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940 ...

in the Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of French Third Rep ...

, and the subsequent Japanese invasion of French Indochina

The was a short undeclared military confrontation between Japan and France in northern French Indochina. Fighting lasted from 22 to 26 September 1940; the same time as the Battle of South Guangxi in the Sino-Japanese War, which was the main ...

, created an opportunity for Vietnamese anti-colonial activists to begin making preparations for independence. On May 19, 1941, Hồ Chí Minh

(: ; born ; 19 May 1890 – 2 September 1969), commonly known as ('Uncle Hồ'), also known as ('President Hồ'), ('Father of the Nation, Old father of the people') and by other Pseudonym, aliases, was a Vietnamese people, Vietnam ...

established the League for the Independence of Vietnam

The Việt Minh (; abbreviated from , chữ Nôm and Hán tự: ; french: Ligue pour l'indépendance du Viêt Nam, ) was a national independence coalition formed at Pác Bó by Hồ Chí Minh on 19 May 1941. Also known as the Việt Minh Fro ...

(Viet Minh), an anti-imperialist coalition brought together to oppose both French colonialism and the Japanese occupation. Following the liberation of Paris

The liberation of Paris (french: Libération de Paris) was a military battle that took place during World War II from 19 August 1944 until the German garrison surrendered the French capital on 25 August 1944. Paris had been occupied by Nazi Germ ...

by Allied forces, in March 1945 the Empire of Japan launched a ''coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

'' in Indochina, establishing the Empire of Vietnam

The Empire of Vietnam (; Literary Chinese and Contemporary Japanese: ; Modern Japanese: ja, ベトナム帝国, Betonamu Teikoku, label=none) was a short-lived puppet state of Imperial Japan governing the former French protectorates of Annam ...

as a puppet state. The new government led by Trần Trọng Kim

Trần Trọng Kim (Chữ Nôm: ; 1883 – December 2, 1953), courtesy name Lệ Thần, was a Vietnamese scholar and politician who served as the Prime Minister of the short-lived Empire of Vietnam, a state established with the support of Impe ...

oversaw widespread reforms including the expansion of education, territorial reunification, the encouragement of mass political participation and the even release of political prisoners, many of whom went over to the Viet Minh and began to actively agitate for the fall of the Empire. In August 1945, due to the resignation of the Vietnamese government and the subsequent surrender of Japan

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy ...

, the Imperial regime in Vietnam fell apart and the Emperor Bảo Đại

Bảo Đại (, vi-hantu, , lit. "keeper of greatness", 22 October 191331 July 1997), born Nguyễn Phúc Vĩnh Thụy (), was the 13th and final emperor of the Nguyễn dynasty, the last ruling dynasty of Vietnam. From 1926 to 1945, he was em ...

officially abdicated.

The Viet Minh responded by launching the August Revolution

The August Revolution ( vi, Cách-mạng tháng Tám), also known as the August General Uprising (), was a revolution launched by the Việt Minh (League for the Independence of Vietnam) against the Empire of Vietnam and the Empire of Japan in ...

, seizing control of most of the country and proclaimed the independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; vi, Việt Nam Dân chủ Cộng hòa), was a socialist state supported by the Soviet Union (USSR) and the People's Republic of China (PRC) in Southeast Asia that existed f ...

on September 2, 1945. However, within a month the French Republic

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

reasserted colonial rule over Vietnam, triggering a mass anti-colonial uprising in Saigon

, population_density_km2 = 4,292

, population_density_metro_km2 = 697.2

, population_demonym = Saigonese

, blank_name = GRP (Nominal)

, blank_info = 2019

, blank1_name = – Total

, blank1_ ...

on September 23. Led by the International Communist League (ICL), the city's populace armed themselves and organized workers' councils

A workers' council or labor council is a form of political and economic organization in which a workplace or municipality is governed by a council made up of workers or their elected delegates. The workers within each council decide on what thei ...

, which they declared to be independent from any political parties. But by October, the workers' militias were defeated by the returning French colonial army. Forced into a retreat into the countryside after surviving a massacre by British and French colonial troops, members of the ICL including Phan Văn Hùm Phan Văn Hùm (9 April 1902 – 1946) was a Vietnamese journalist, philosopher and revolutionary in French colonial Cochinchina who, from 1930, participated in the Trotskyist left opposition to the Communist Party of Nguyen Ai Quoc (Ho Chi Minh).

...

and Tạ Thu Thâu

Tạ Thu Thâu (1906–1945) in the 1930s was the principal representative of Trotskyism in Vietnam and, in colonial Cochinchina, of left opposition to the Indochinese Communist Party (PCI) of Nguyen Ai Quoc (Ho Chi Minh). He joined to Left Oppos ...

were hunted down and executed by the Viet Minh. After the First Indochina War

The First Indochina War (generally known as the Indochina War in France, and as the Anti-French Resistance War in Vietnam) began in French Indochina from 19 December 1946 to 20 July 1954 between France and Việt Minh (Democratic Republic of Vi ...

, Vietnam was partitioned between the communist-held North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

and the anti-communist South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

.

Some of those who survived escaped to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, one of whom was Ngo Van

Ngô Văn Xuyết (Tan Lo, near Saigon, 1913–Paris, 1 January 2005), alias Ngô Văn was a Vietnamese revolutionary who chronicled labour and peasant insurrections caught "in the crossfire" between the colonial French and the Indochinese Commun ...

, who met a number of Spanish anarchists

Anarchism in Spain has historically gained some support and influence, especially before Francisco Franco's victory in the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939, when it played an active political role and is considered the end of the golden age of cl ...

and Poumistas that were also in exile in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

. The encounters with the Spanish anarchist exiles and the stories of their experiences during the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

, which Van noted parallels with the Vietnamese experience, led him to permanently distance himself from Bolshevism

Bolshevism (from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined party of social revolution, fo ...

, criticizing communist parties

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. A ...

as seeking to form "the nucleus of a new ruling class and bring about nothing more than a new system of exploitation.". Van found a political home with the International Workers' Association International Workers' Association may refer to:

* International Workingmen's Association

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation which aimed at ...

(IWA), which supported his criticisms of the Vietnamese Trotskyist exiles that remained supportive of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. He also joined a Libertarian Marxist

Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing,Diemer, Ulli (1997)"What Is Libertarian Socialism?" The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 4 August 2019. anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarianLong, Roderick T. (201 ...

group around Maximilien Rubel

Maximilien Rubel (10 October 1905, in Chernivtsi – 28 February 1996, in Paris) was a famous Marxist historian and council communist.

Rubel was born in western Ukraine and was educated in law and philosophy in Vienna and Chernivtsi National Un ...

and was introduced to the works of Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

, who had previously inspired the individualist anarchist philosophy of Nguyễn An Ninh

Nguyễn An Ninh (September 5, 1900 – August 14, 1943) was a radical Vietnamese political journalist and publicist in French colonial Cochinchina (southern Vietnam). An independent and charismatic figure, Nguyen An Ninh was able to conciliate ...

. Van would later go on to participate in a factory occupation

Occupation of factories is a method of the workers' movement used to prevent lock outs. They may sometimes lead to "recovered factories", in which the workers self-manage the factories.

They have been used in many strike actions, including:

* ...

during the events of May 1968

The following events occurred in May 1968:

May 1, 1968 (Wednesday)

*CARIFTA, the Caribbean Free Trade Association, was formally created as an agreement between Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Guyana, and Trinidad and Tobago.

*RAF Strike Co ...

. He retired a few years after the Fall of Saigon

The Fall of Saigon, also known as the Liberation of Saigon by North Vietnamese or Liberation of the South by the Vietnamese government, and known as Black April by anti-communist overseas Vietnamese was the capture of Saigon, the capital of ...

and the reunification

A political union is a type of political entity which is composed of, or created from, smaller polities, or the process which achieves this. These smaller polities are usually called federated states and federal territories in a federal governmen ...

of Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

, and was finally able to return to his home country in 1998, where he noted that Vietnamese workers "still do not enjoy collective ownership of the means of production, nor ave

''Alta Velocidad Española'' (''AVE'') is a service of high-speed rail in Spain operated by Renfe, the Spanish national railway company, at speeds of up to . As of December 2021, the Spanish high-speed rail network, on part of which the AVE s ...

time for reflection, nor the possibility of making their own decisions, nor means of expression."

21st century

In March 2021, the anarchist "clowder

{{Short pages monitor