Amistad (ship replica) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''La Amistad'' (;

Captained by Ferrer, ''La Amistad'' left Havana on June 28, 1839, for the small port of Guanaja, near

Captained by Ferrer, ''La Amistad'' left Havana on June 28, 1839, for the small port of Guanaja, near

A widely publicized court case ensued in New Haven to settle legal issues about the ship and the status of the Mende captives. They were at risk of execution if convicted of

A widely publicized court case ensued in New Haven to settle legal issues about the ship and the status of the Mende captives. They were at risk of execution if convicted of

''Amistad'': Seeking Freedom in Connecticut, a National Park Service ''Discover Our Shared Heritage'' Travel Itinerary

* ttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MjOorZcU2MY ''Freedom Schooner Amistad'' sailing YouTube video

The ''Amistad'' AffairThe current owners of the replica ''Amistad''“Amistad Connecticut: A Legacy Reborn,”

1998-02-27, The Walter J. Brown Media Archives & Peabody Awards Collection at the

Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Cana ...

for ''Friendship'') was a 19th-century two- masted schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoon ...

, owned by a Spaniard colonizing Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

. It became renowned in July 1839 for a slave revolt by Mende captives, who had been captured and sold to European slave traders, and illegally transported by a Portuguese ship from West Africa to Cuba in violation of existing European treaties against the Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

. Two Spanish plantation owners, Don José Ruiz and Don Pedro Montes, bought 53 captives, including four children, in Havana, Cuba

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

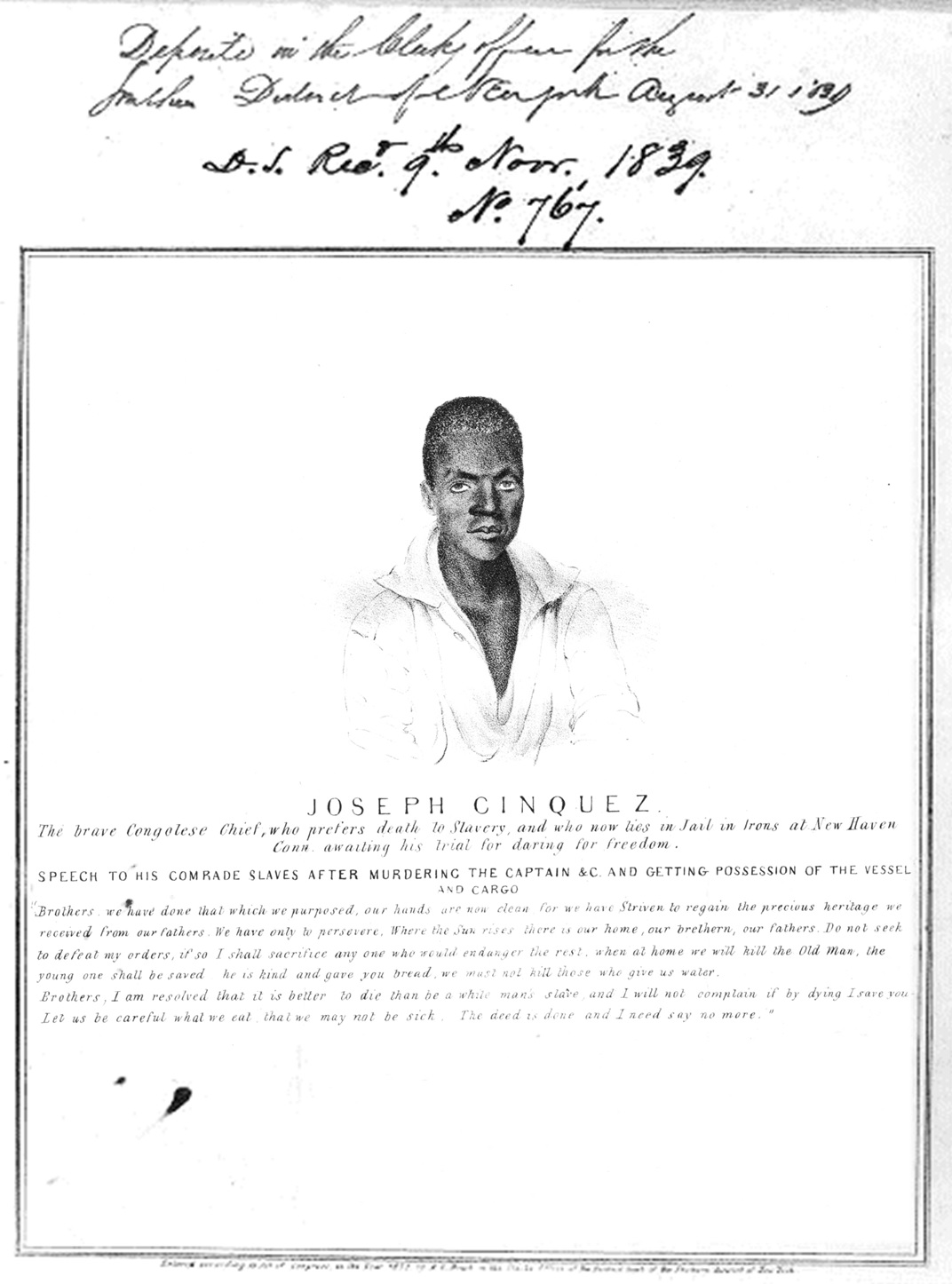

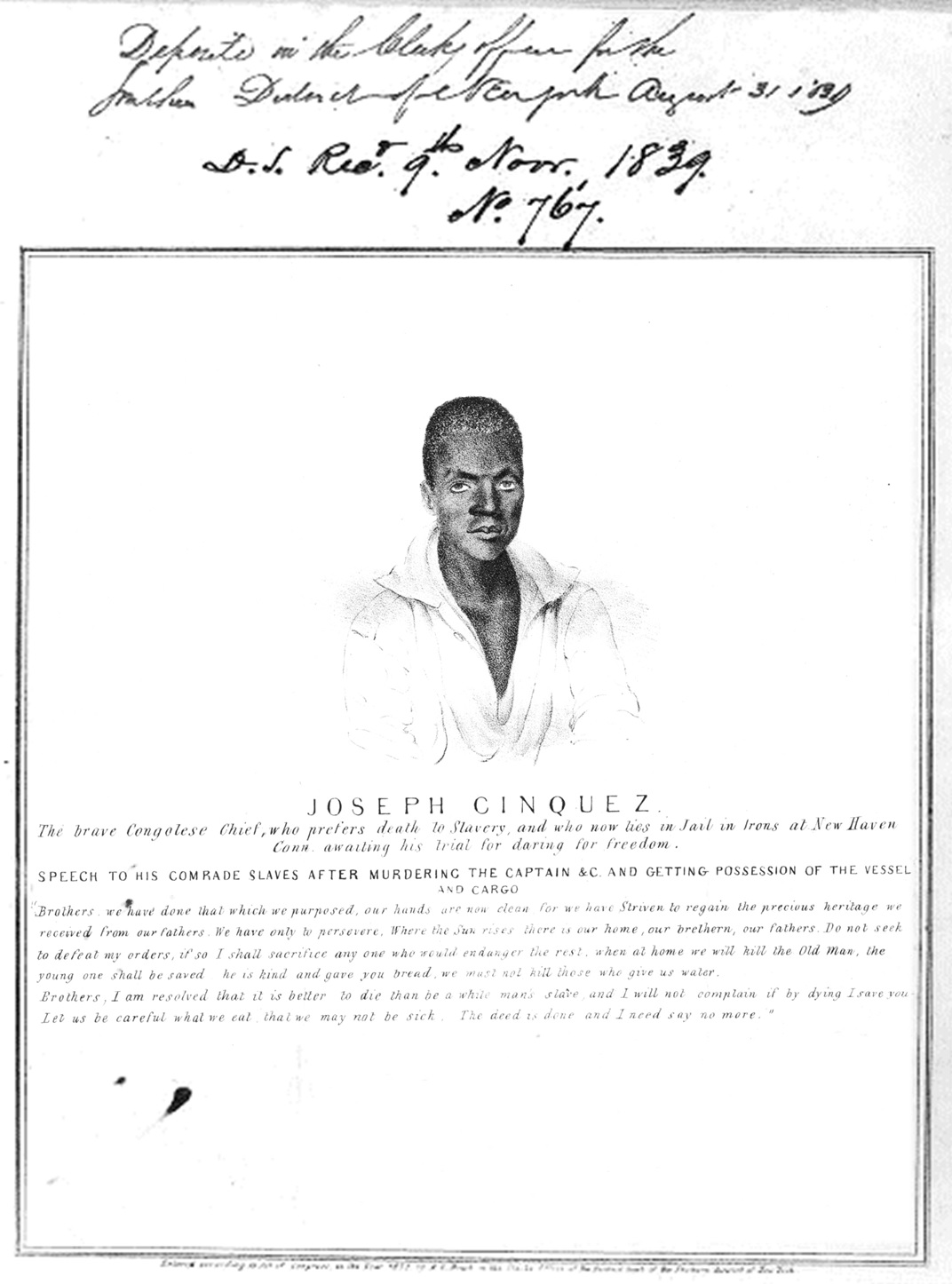

, and were transporting them on the ship to their plantations near Puerto Príncipe (modern Camagüey, Cuba). The revolt began after the schooner's cook jokingly told the slaves that they were to be "killed, salted, and cooked." Sengbe Pieh, a Mende man, also known as Joseph Cinqué

Sengbe Pieh (18141879), also known as Joseph Cinqué or Cinquez and sometimes referred to mononymously as Cinqué, was a West African man of the Mende people who led a revolt of many Africans on the Spanish slave ship ''La Amistad'' in July 1839. ...

, unshackled himself and the others on the third day and started the revolt. They took control of the ship, killing the captain and the cook. In the melee

A melee ( or , French: mêlée ) or pell-mell is disorganized hand-to-hand combat in battles fought at abnormally close range with little central control once it starts. In military aviation, a melee has been defined as " air battle in which ...

, three Africans were also killed.

Pieh ordered Ruiz and Montes to sail to Africa. Instead, Ruiz and Montes sailed north, up the east coast of the United States, sure that the ship would be intercepted and the Africans returned to Cuba as slaves. A US ship, the revenue cutter

A cutter is a type of watercraft. The term has several meanings. It can apply to the rig (or sailplan) of a sailing vessel (but with regional differences in definition), to a governmental enforcement agency vessel (such as a coast guard or bor ...

''Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered on ...

'', seized ''Amistad'' off Montauk Point

Montauk ( ) is a hamlet and census-designated place (CDP) in the Town of East Hampton in Suffolk County, New York, on the eastern end of the South Shore of Long Island. As of the 2020 United States census, the CDP's population was 4,318.

The ...

in Long Island, New York. Pieh and his group escaped the ship but were caught offshore by citizens. They were incarcerated in New Haven, Connecticut

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134,02 ...

, on charges of murder and piracy. The man who captured Pieh and his group claimed them as property. ''La Amistad'' was towed to New London, Connecticut, and those remaining on the ship were arrested. None of the 43 survivors on the ship spoke English, so they could not explain what had taken place. Eventually, language professor Josiah Gibbs

Josiah Willard Gibbs (; February 11, 1839 – April 28, 1903) was an American scientist who made significant theoretical contributions to physics, chemistry, and mathematics. His work on the applications of thermodynamics was instrumental in t ...

found an interpreter, James Covey

James Benjamin Covey (''né'' Kaweli; c. 1825 – 12 October 1850) was a sailor, remembered today chiefly for his role as Language interpretation, interpreter during the legal proceedings in the Federal judiciary of the United States, United Stat ...

, and learned of the abduction.

Two lawsuits were filed. The first case was brought by the ''Washington'' ship officers over property claims and the second case was the Spanish being charged with enslaving Africans. Spain requested President Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (Uni ...

to return the African captives to Cuba under international treaty.

Because of issues of ownership and jurisdiction, the case gained international attention. Known as ''United States v. The Amistad

''United States v. Schooner Amistad'', 40 U.S. (15 Pet.) 518 (1841), was a United States Supreme Court case resulting from the rebellion of Africans on board the Spanish schooner ''La Amistad'' in 1839.. It was an unusual freedom suit that in ...

'' (1841), the case was finally decided by the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

in favor of the Mende, restoring their freedom. It became a symbol in the United States in the movement to abolish slavery.

Description

''La Amistad'' was a 19th-century two- masted schooner of about . In 1839 it was owned by Ramón Ferrer, a Spanish national. Strictly speaking, ''La Amistad'' was not a typicalslave ship

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea coast ...

, as it was not designed like others to traffic massive numbers of enslaved Africans, nor did it engage in the Middle Passage

The Middle Passage was the stage of the Atlantic slave trade in which millions of enslaved Africans were transported to the Americas as part of the triangular slave trade. Ships departed Europe for African markets with manufactured goods (first ...

of Africans to the Americas. The ship engaged in the shorter, domestic coastwise trade around Cuba and islands and coastal nations in the Caribbean. The primary cargo carried by ''La Amistad'' was sugar-industry products. It carried a limited number of passengers and enslaved Africans being trafficked for delivery or sale around the island.

History

1839 slave revolt

Captained by Ferrer, ''La Amistad'' left Havana on June 28, 1839, for the small port of Guanaja, near

Captained by Ferrer, ''La Amistad'' left Havana on June 28, 1839, for the small port of Guanaja, near Puerto Príncipe, Cuba

Puerto, a Spanish word meaning ''seaport'', may refer to:

Places

*El Puerto de Santa María, Andalusia, Spain

*Puerto, a seaport town in Cagayan de Oro City, Philippines

*Puerto Colombia, Colombia

*Puerto Cumarebo, Venezuela

*Puerto Galera, Orient ...

, with some general cargo and 53 African slaves bound for the sugar plantation where they were to be delivered. These 53 Mende captives (49 adults and four children) had been captured by African slave catchers or otherwise enslaved in Mendiland

Mendiland is part of the extreme southwest portion of Sierra Leone on the western coast of Africa, where the Mende tribe

The Mende are one of the two largest ethnic groups in Sierra Leone; their neighbours, the Temne people, constitute the l ...

(in modern-day Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierra ...

), sold to European slave traders and illegally transported from Africa to Havana, mostly aboard the Portuguese slave ship '' Tecora, Teçora'', to be sold in Cuba. Although the United States and Britain had banned the Atlantic slave trade, Spain had not abolished slavery in its colonies. The crew of ''La Amistad'', lacking purpose-built slave quarters, placed half the captives in the main hold and the other half on deck. The captives were relatively free to move about, which aided their revolt and commandeering of the vessel. In the main hold below decks, the captives found a rusty file and sawed through their manacles.

On about July 1, once free, the men below quickly went up on deck. Armed with machete-like cane knives, they attacked the crew, successfully gaining control of the ship, under the leadership of Sengbe Pieh

Sengbe is a chiefdom in Koinadugu District of Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the ...

(later known in the United States as Joseph Cinqué

Sengbe Pieh (18141879), also known as Joseph Cinqué or Cinquez and sometimes referred to mononymously as Cinqué, was a West African man of the Mende people who led a revolt of many Africans on the Spanish slave ship ''La Amistad'' in July 1839. ...

). They killed the captain and some of the crew, but spared José Ruiz and Pedro Montes, the two owners of the slaves, so that they could guide the ship back to Africa. While the Mende demanded to be returned home, the navigator Montes deceived them about the course, maneuvering the ship north along the North American coast until they reached the eastern tip of Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United Sta ...

, New York.

Several New York pilot boats came across ''Amistad'' as on 21 August 1839, when she was discovered thirty miles southeast of Sandy Hook

Sandy Hook is a barrier spit in Middletown Township, Monmouth County, New Jersey, United States.

The barrier spit, approximately in length and varying from wide, is located at the north end of the Jersey Shore. It encloses the southern en ...

by the pilot-boat ''Blossom'' who supplied the men with water and bread. When they attempted to board the pilot-boat to escape, the pilot-boat cut the rope that was attached to the ''Amistad.'' The pilots then communicated what they felt was a Slave ship

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea coast ...

to the Collector of the Port of New York

The Collector of Customs at the Port of New York, most often referred to as Collector of the Port of New York, was a federal officer who was in charge of the collection of import duties on foreign goods that entered the United States by ship at t ...

. Two days later, the ''Gratitude

Gratitude, thankfulness, or gratefulness is from the Latin word ''gratus,'' which means "pleasing" or "thankful." Is regarded as a feeling of appreciation (or similar positive response) by a recipient of another's kindness. This can be gifts, h ...

'' pilot boat came across the ''La Amistad'' when she was twenty-five miles east of Fire Island

Fire Island is the large center island of the outer barrier islands parallel to the South Shore of Long Island, in the U.S. state of New York.

Occasionally, the name is used to refer collectively to not only the central island, but also Long ...

. When Captain Seaman of the ''Gratitude'' wanted to put a pilot aboard, one of the ringleaders of the ''La Amistad '' ordered the men to fire on the ''Gratitude''. Gun shots hit the pilot boat but she was able to escape.

Discovered by the naval brig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square rig, square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the ...

while on surveying duties, ''La Amistad'' was taken into United States custody.

Court case

The ''Washington'' officers brought the first case to federal district court over salvage claims while the second case began in a Connecticut court after the state arrested the Spanish traders on charges of enslaving free Africans. The Spanish foreign minister, however, demanded that ''Amistad'' and its cargo be released from custody and the "slaves" sent to Cuba for punishment by Spanish authorities. While the Van Buren administration accepted the Spanish crown's argument, Secretary of State John Forsyth explained that the president could not order the release of ''Amistad'' and its cargo because the executive could not interfere with the judiciary under American law. He could also not release the Spanish traders from imprisonment in Connecticut because that would constitute federal intervention in a matter of state jurisdiction. AbolitionistsJoshua Leavitt

Rev. Joshua Leavitt (September 8, 1794, Heath, Massachusetts – January 16, 1873, Brooklyn, New York) was an American Congregationalist minister and former lawyer who became a prominent writer, editor and publisher of abolitionist literature. ...

, Lewis Tappan

Lewis Tappan (May 23, 1788 – June 21, 1873) was a New York abolitionist who worked to achieve freedom for the enslaved Africans aboard the '' Amistad''. Tappan was also among the founders of the American Missionary Association in 1846, which ...

, and Simeon Jocelyn Simeon Jocelyn (1799-1879) was a white pastor, abolitionist, and social activist for African-American civil rights and educational opportunities in New Haven, Connecticut, during the 19th century. He is known for his attempt to establish America's f ...

formed the Amistad Committee to raise funds for the defense of ''Amistads captives. Former President John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

represented the captives in court.

A widely publicized court case ensued in New Haven to settle legal issues about the ship and the status of the Mende captives. They were at risk of execution if convicted of

A widely publicized court case ensued in New Haven to settle legal issues about the ship and the status of the Mende captives. They were at risk of execution if convicted of mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among member ...

. They became a popular cause among abolitionists in the United States. Since 1808, the United States and Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

had prohibited the international slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. In order to avoid the international prohibition on the African slave trade, the ship's owners fraudulently described the Mende as having been born in Cuba and said they were being sold in the Spanish domestic slave trade. The court had to determine if the Mende were to be considered salvage and thus the property of naval officers who had taken custody of the ship (as was legal in such cases), the property of the Cuban buyers, or the property of Spain, as Queen Isabella II

Isabella II ( es, Isabel II; 10 October 1830 – 9 April 1904), was Queen of Spain from 29 September 1833 until 30 September 1868.

Shortly before her birth, the King Ferdinand VII of Spain issued a Pragmatic Sanction to ensure the successio ...

claimed, via Spanish ownership of the ''Amistad.'' A question was whether the circumstances of the capture and transport of the Mende meant they were legally free and had acted as free men rather than slaves.

After judges ruled in favor of the Africans in the district and circuit courts, the ''United States v. The Amistad

''United States v. Schooner Amistad'', 40 U.S. (15 Pet.) 518 (1841), was a United States Supreme Court case resulting from the rebellion of Africans on board the Spanish schooner ''La Amistad'' in 1839.. It was an unusual freedom suit that in ...

'' case reached the US Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point of ...

on appeal. In 1841, it ruled that the Mende had been illegally transported and held as slaves, and had rebelled in self-defense. It ordered them freed. Although the US government did not provide any aid, thirty-five survivors returned to Africa in 1842, aided by funds raised by the United Missionary Society, a black group founded by James W.C. Pennington. He was a Congregational

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its ...

minister and fugitive slave in Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

, New York, who was active in the abolitionist movement. The Spanish government claimed that the slaves were Spanish citizens not of African origin. This created a lot of tension between the U.S. government, the Spanish crown, and the British government, which had outlawed the slave trade in the British Empire with the Slave Trade Act of 1807

The Slave Trade Act 1807, officially An Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom prohibiting the slave trade in the British Empire. Although it did not abolish the practice of slavery, it ...

and had recently abolished slavery in the British Empire with the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.

Later years

After being moored at the wharf behind the US Custom House inNew London, Connecticut

New London is a seaport city and a port of entry on the northeast coast of the United States, located at the mouth of the Thames River in New London County, Connecticut. It was one of the world's three busiest whaling ports for several decades ...

, for a year and a half, ''La Amistad'' was auctioned off by the U.S. Marshal

The United States Marshals Service (USMS) is a federal law enforcement agency in the United States. The USMS is a bureau within the U.S. Department of Justice, operating under the direction of the Attorney General, but serves as the enforce ...

in October 1840. Captain George Hawford, of Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, Rhode Island, Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, ...

, purchased the vessel and then needed an Act of Congress

An Act of Congress is a statute enacted by the United States Congress. Acts may apply only to individual entities (called Public and private bills, private laws), or to the general public (Public and private bills, public laws). For a Bill (law) ...

passed to register it. He renamed it ''Ion''. In late 1841, he sailed ''Ion'' to Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = " Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, e ...

and Saint Thomas with a typical New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

cargo of onions, apples, live poultry, and cheese.

After sailing ''Ion'' for a few years, Hawford sold it in Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands—Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La Désirade, and the ...

in 1844. There is no record of what became of ''Ion'' under the new French owners in the Caribbean.

Legacy

The Amistad Memorial stands in front ofNew Haven City Hall and County Courthouse

The New Haven City Hall and County Courthouse is located at 161 Church Street in the Downtown section of New Haven, Connecticut. The city hall building, designed by Henry Austin, was built in 1861; the old courthouse building, now an annex, desig ...

in New Haven, Connecticut, where many of the events related to the affair in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

occurred.

The Amistad Research Center

The Amistad Research Center (ARC) is an independent archives and manuscripts repository in the United States that specializes in the history of African Americans and ethnic minorities. It is one of the first institutions of its kind in the United ...

at Tulane University

Tulane University, officially the Tulane University of Louisiana, is a private university, private research university in New Orleans, Louisiana. Founded as the Medical College of Louisiana in 1834 by seven young medical doctors, it turned into ...

, New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, is devoted to research about slavery, abolition, civil rights and African Americans; it commemorates the revolt of slaves on the ship by the same name. A collection of portraits of ''La Amistad'' survivors that were drawn by William H. Townsend during the survivors' trial are held in the collection of Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

.

Replica

Between 1998 and 2000, artisans atMystic Seaport

Mystic Seaport Museum or Mystic Seaport: The Museum of America and the Sea in Mystic, Connecticut is the largest maritime museum in the United States. It is notable for its collection of sailing ships and boats and for the re-creation of the craf ...

, Mystic, Connecticut

Mystic is a village and census-designated place (CDP) in Groton, Connecticut, Groton and Stonington, Connecticut, United States.

Historically, Mystic was a significant Connecticut seaport with more than 600 ships built over 135 years starting in ...

, built a replica

A 1:1 replica is an exact copy of an object, made out of the same raw materials, whether a molecule, a work of art, or a commercial product. The term is also used for copies that closely resemble the original, without claiming to be identical. Al ...

of ''La Amistad'', using traditional skills and construction techniques common to wooden schooners built in the 19th century, but using modern materials and engines. Officially named ''Amistad'', it was promoted as "Freedom Schooner ''Amistad''". The modern-day ship is not an exact replica of ''La Amistad'', as it is slightly longer and has higher freeboard

In sailing and boating, a vessel's freeboard

is the distance from the waterline to the upper deck level, measured at the lowest point of sheer where water can enter the boat or ship. In commercial vessels, the latter criterion measured relativ ...

. There were no old blueprints of the original.

The new schooner was built using a general knowledge of the Baltimore Clipper

A Baltimore Clipper is a fast sailing ship historically built on the mid-Atlantic seaboard of the United States of America, especially at the port of Baltimore, Maryland. An early form of clipper, the name is most commonly applied to two-masted ...

s and art drawings from the era. Some of the tools used in the project were the same as those that might have been used by a 19th-century shipwright, while others were powered. Tri-Coastal Marine, designers of "Freedom Schooner ''Amistad''", used modern computer technology to develop plans for the vessel. Bronze bolts are used as fastenings throughout the ship. ''Freedom Schooner Amistad'' has an external ballast keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

made of lead and two Caterpillar

Caterpillars ( ) are the larval stage of members of the order Lepidoptera (the insect order comprising butterflies and moths).

As with most common names, the application of the word is arbitrary, since the larvae of sawflies (suborder Sym ...

diesel engines. None of this technology was available to 19th-century builders.

"Freedom Schooner ''Amistad''" was operated by Amistad America, Inc., based in New Haven, Connecticut. The ship's mission was to educate the public on the history of slavery, abolition, discrimination, and civil rights. The homeport is New Haven, where the ''Amistad'' trial took place. It has also traveled to port cities for educational opportunities. It was also the State Flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

and Tall ship

A tall ship is a large, traditionally- rigged sailing vessel. Popular modern tall ship rigs include topsail schooners, brigantines, brigs and barques. "Tall ship" can also be defined more specifically by an organization, such as for a race or fe ...

Ambassador of Connecticut. The ship made several commemorative voyages: one in 2007 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

in Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

(1807) and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

(1808), and one in 2010 to celebrate the 10th anniversary of its 2000 launching at Mystic Seaport. It undertook a two-year refit at Mystic Seaport from 2010 and was subsequently mainly used for sea training in Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

and film work.

In 2013 Amistad America lost its non-profit organization

A nonprofit organization (NPO) or non-profit organisation, also known as a non-business entity, not-for-profit organization, or nonprofit institution, is a legal entity organized and operated for a collective, public or social benefit, in co ...

status after failing to file tax returns for three years and amid concern of the accountability for public funding from the state of Connecticut. The company was later put into liquidation, and in November 2015 a new non-profit, Discovering Amistad Inc., purchased the ship from the receiver. ''Amistad'' has now been restored to educational and promotional activity in New Haven, Connecticut.

In popular culture

*On 2 September 1839, a play entitled ''The Long, Low Black Schooner'', based on the revolt, opened inNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

and played to full houses. (''La Amistad'' was painted black at the time of the revolt.)

*The slave revolt aboard the ''La Amistad,'' the background of the slave trade, and its subsequent trial are retold in a celebrated poem by Robert Hayden

Robert Hayden (August 4, 1913February 25, 1980) was an American poet, essayist, and educator. He served as Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress from 1976 to 1978, a role today known as US Poet Laureate. He was the first African-Americ ...

entitled "Middle Passage

The Middle Passage was the stage of the Atlantic slave trade in which millions of enslaved Africans were transported to the Americas as part of the triangular slave trade. Ships departed Europe for African markets with manufactured goods (first ...

"'','' first published in 1962.

* In Robert Skimin Robert Skimin (July 30, 1929 in Belden, Ohio – May 9, 2011 in El Paso, Texas) was a U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and i ...

's novel ''Gray Victory

''Gray Victory'' is a 1988 alternate history novel by Robert Skimin, taking place in an alternate 1866 where the Confederacy won its independence.

Plot introduction

The first point of divergence occurs during the American Civil War in May 1864, ...

'' (1988), depicting an alternate history

Alternate history (also alternative history, althist, AH) is a genre of speculative fiction of stories in which one or more historical events occur and are resolved differently than in real life. As conjecture based upon historical fact, altern ...

in which the South won the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, a group of abolitionist conspirators infiltrating Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

calls itself "Amistad".

*The film '' Amistad'' (1997), directed by Steven Spielberg

Steven Allan Spielberg (; born December 18, 1946) is an American director, writer, and producer. A major figure of the New Hollywood era and pioneer of the modern blockbuster, he is the most commercially successful director of all time. Spie ...

, dramatized the historical incidents. Major actors were Morgan Freeman

Morgan Freeman (born June 1, 1937) is an American actor, director, and narrator. He is known for his distinctive deep voice and various roles in a wide variety of film genres. Throughout his career spanning over five decades, he has received ...

, as a freed slave-turned-abolitionist in New Haven; Anthony Hopkins

Sir Philip Anthony Hopkins (born 31 December 1937) is a Welsh actor, director, and producer. One of Britain's most recognisable and prolific actors, he is known for his performances on the screen and stage. Hopkins has received many accolad ...

, as John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

; Matthew McConaughey

Matthew David McConaughey ( ; born November 4, 1969) is an American actor. He had his breakout role with a supporting performance in the coming-of-age comedy '' Dazed and Confused'' (1993). After a number of supporting roles, his first succes ...

, as Roger Sherman Baldwin

Roger Sherman Baldwin (January 4, 1793 – February 19, 1863) was an American politician who served as the 32nd Governor of Connecticut from 1844 to 1846 and a United States senator from 1847 to 1851. As a lawyer, his career was most notable ...

, an unorthodox, but influential lawyer; and Djimon Hounsou

Djimon Gaston Hounsou (; ; born April 24, 1964) is a Beninese-American actor and model. He began his career appearing in music videos. He made his film debut in '' Without You I'm Nothing'' (1990) and earned widespread recognition for his role as ...

, as Cinque (Sengbe Peah).

* The 1999 hit single "My Love Is Your Love

''My Love Is Your Love'' is the fourth studio album by American singer Whitney Houston, released worldwide on November 17, 1998. It was Houston's first studio album in eight years, following ''I'm Your Baby Tonight'' (1990) although she had parti ...

", performed by Whitney Houston

Whitney Elizabeth Houston (August 9, 1963 – February 11, 2012) was an American singer and actress. Nicknamed "The Voice", she is one of the bestselling music artists of all time, with sales of over 200 million records worldwide. Houston in ...

, references the "chains of Amistad".

*In January 2011, Random House

Random House is an American book publisher and the largest general-interest paperback publisher in the world. The company has several independently managed subsidiaries around the world. It is part of Penguin Random House, which is owned by Germ ...

published ''Ardency'', a collection of poems written over 20 years by American poet Kevin Young which "gathers here a chorus of voices that tells the story of the Africans who mutinied on board the slave ship ''Amistad''".

See also

*African Slave Trade Patrol

African Slave Trade Patrol was part of the Blockade of Africa suppressing the Atlantic slave trade between 1819 and the beginning of the American Civil War in 1861. Due to the abolitionist movement in the United States, a squadron of U.S. Navy ...

*Bibliography of early American naval history

Historical accounts for early U.S. naval history now occur across the spectrum of two and more centuries. This Bibliography lends itself primarily to reliable sources covering early U.S. naval history beginning around the American Revolution per ...

*Blockade of Africa

The Blockade of Africa began in 1808 after the United Kingdom outlawed the Atlantic slave trade, making it illegal for British ships to transport slaves. The Royal Navy immediately established a presence off Africa to enforce the ban, called ...

* ''Creole'' case

*John Quincy Adams and abolitionism

Like most contemporaries, John Quincy Adams' views on slavery evolved over time. Historian David F. Ericson asks why he never became an abolitionist. He never joined the movement called "abolitionist" by historians—the one led by William Lloyd G ...

* List of historical schooners

*List of ships captured in the 19th century

Throughout naval history during times of war battles, blockades, and other patrol missions would often result in the capture of enemy ships or those of a neutral country. If a ship proved to be a valuable prize efforts would sometimes be made to ...

References

Further reading

* * * *External links

''Amistad'': Seeking Freedom in Connecticut, a National Park Service ''Discover Our Shared Heritage'' Travel Itinerary

* ttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MjOorZcU2MY ''Freedom Schooner Amistad'' sailing YouTube video

The ''Amistad'' Affair

1998-02-27, The Walter J. Brown Media Archives & Peabody Awards Collection at the

University of Georgia

, mottoeng = "To teach, to serve, and to inquire into the nature of things.""To serve" was later added to the motto without changing the seal; the Latin motto directly translates as "To teach and to inquire into the nature of things."

, establ ...

, American Archive of Public Broadcasting

The American Archive of Public Broadcasting (AAPB) is a collaboration between the Library of Congress and WGBH Educational Foundation, founded through the efforts of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. The AAPB is a national effort to digitall ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:La Amistad

1839 in the United States

Schooners

Slave rebellions in the United States

Replica ships

Two-masted ships

Museum ships in Connecticut

Slave ships

Museums in New Haven, Connecticut

Captured ships

Maritime incidents in July 1839

Maritime incidents involving slave ships

Fugitive American slaves

American rebel slaves

Abolitionism in the United States

Post-1808 importation of slaves to the United States