Amissville, Virginia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Amissville ( ) is an

Amissville was also the site of a sharp cavalry fight in November 1862, at Corbin's Crossroads, when Gen.

Amissville was also the site of a sharp cavalry fight in November 1862, at Corbin's Crossroads, when Gen.

The geology of Amissville and the surrounding vicinity consists of several units. Predominant and oldest (approximately 704 million years old, +/- 5 million years, based on the U- Pb

The geology of Amissville and the surrounding vicinity consists of several units. Predominant and oldest (approximately 704 million years old, +/- 5 million years, based on the U- Pb

Amissville.com

{{authority control Unincorporated communities in Rappahannock County, Virginia Unincorporated communities in Virginia Populated places established in 1810 1810 establishments in Virginia

unincorporated community

An unincorporated area is a region that is not governed by a local municipal corporation. Widespread unincorporated communities and areas are a distinguishing feature of the United States and Canada. Most other countries of the world either have ...

in Rappahannock County

Rappahannock County is a county located in the northern Piedmont region of the Commonwealth of Virginia, US, adjacent to Shenandoah National Park. As of the 2020 Census, the population was 7,348. Its county seat is Washington. The name "Rappah ...

in the U.S. commonwealth of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

. It is located on U.S. Route 211 about halfway between Warrenton and the small town of Washington, Virginia

The town of Washington, Virginia, is a historic village located in the eastern foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains near Shenandoah National Park. The entire town is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as a historic district, Wa ...

.

The Locust Grove/R.E. Luttrell Farmstead and Meadow Grove Farm are listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic ...

.

History

The land on which the village of Amissville is now situated was part of the 5.3 million acre Northern Neck Proprietary owned in the 1700s byThomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron

Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron (22 October 16939 December 1781), was a Scottish peer. He was the son of Thomas Fairfax, 5th Lord Fairfax of Cameron, and Catherine Colepeper, daughter of Thomas Colepeper, 2nd Baron Colepeper.

The ...

. In 1649 King Charles II of England, then in exile in France after the execution of his father, Charles I, had given this unmapped and unsettled region to seven loyal supporters. By 1688 the proprietary was owned solely by Thomas Lord Culpeper whose only child married Thomas 5th Lord Fairfax in 1690. They acquired the proprietary on the death of Lord Culpeper and the region became synonymous with the Fairfax name. In 1719, Thomas 6th Lord Fairfax inherited the land. During 1747 to 1766, Lord Fairfax granted land that encompassed the area of today's Amissville to five individuals: Thomas Burk received 200 acres, Samuel Scott received 270 acres and 470 acres, James Genn received two grants of 400 acres each, Gabriel Jones received 380 acres, and Philip Edward Jones received 452 acres. It is widely believed that individuals with surnames Amiss and Bayse received land grants from Lord Fairfax in the Amissville area. However, there are no grants to anyone with these surnames recorded in the Virginia Colonial land grant books maintained by the Library of Virginia. Rather, Joseph Amiss and Edmond Bayse purchased existing land grants. On 14 July 1766 Joseph Amiss purchased, for 40 pounds, the 380 acres that had been granted to Gabriel Jones. On 15 October 1770 Edmond Bayse purchased, for 90 pounds, the 800 acres that had been granted to James Genn. On 1 July 1794, Joseph Amiss distributed his land and slaves as gifts to his three living sons William, Philip, and Thomas, and his grandsons William (son of William) and John (son of Thomas). In return, Joseph and his wife Constant were given a life estate to the property (10)Constant is believed to have been a daughter of Gabriel Jones. The sons and grandsons and their children purchased additional land in the Amissville area. On 20 April 1778, Edmond Bayse gave his son Elijamon 190 acres of the 800 acres that Edmond had acquired in 1770. This was the northern part of the 800 acres, located adjacent to today's Route 211. Although Elijamon sold this land in 1789, he and his children acquired other land in the Amissville area and became major landowners. The post office was established on 2 October 1810, with Thomas Amiss as its first postmaster. In 1854, Amissville was described as a small post-village with about 75 inhabitants.

US Civil War

Amissville is near the site of a minor action on July 24, 1863, involving George A. Custer'sMichigan Brigade The Michigan Brigade, sometimes called the Wolverines, the Michigan Cavalry Brigade or Custer's Brigade, was a brigade of cavalry in the volunteer Union Army during the latter half of the American Civil War. Composed primarily of the 1st Michigan ...

of cavalry following the Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

loss at Gettysburg. Longstreet's corps and Gen. A. P. Hill's corps

Corps (; plural ''corps'' ; from French , from the Latin "body") is a term used for several different kinds of organization. A military innovation by Napoleon I, the formation was first named as such in 1805. The size of a corps varies great ...

were retreating from Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

through the Chester Gap

Chester Gap, sometimes referred to as Happy Creek Gap for the creek that runs down its western slope, is a wind gap in the Blue Ridge Mountains on the border of Rappahannock County, Fauquier County and Warren County in Virginia. The gap is trav ...

and south on the Richmond Road towards Culpeper. Custer and his troops traveled from their headquarters and camp near Amissville and attacked with cavalry and artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

from the southern slope of Battle Mountain (about 5 miles southwest of the village), but his forces were vastly outnumbered and after a brisk and severe fight, forced to retreat north and east over Battle Mountain back to Amissville. Two of Custer's men were awarded the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valo ...

in 1893 for their part in capturing Confederate artillery at Battle Mountain. Battle Mountain and Little Battle Mountain were named not for the military engagement but for the Bataille family which lived near the two elevations in the 1700s. Bataille was later corrupted to Battle Mountain and Little Battle Mountain, the names they bear today.

J.E.B. Stuart

James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart (February 6, 1833May 12, 1864) was a United States Army officer from Virginia who became a Confederate States Army general during the American Civil War. He was known to his friends as "Jeb,” from the initials of ...

's Confederate cavalry were heading to Culpeper County

Culpeper County is a county located along the borderlands of the northern and central region of the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 United States Census, the population was 52,552. Its county seat and only incorporated community is Cul ...

following the Battle of Antietam in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

. At Corbin's crossroads, during the fight, Gen. Stuart narrowly escaped death when he turned his head and a Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

bullet clipped off half of his moustache

A moustache (; en-US, mustache, ) is a strip of facial hair grown above the upper lip. Moustaches have been worn in various styles throughout history.

Etymology

The word "moustache" is French, and is derived from the Italian ''mustaccio'' ...

. The site of the engagement is about 3/4 of a mile south of the present village of Amissville.

In late August 1862, Gen. Stuart and his cavalry were scouting around Maj. Gen. John Pope's Federal Army of Virginia

The Army of Virginia was organized as a major unit of the Union Army and operated briefly and unsuccessfully in 1862 in the American Civil War. It should not be confused with its principal opponent, the Confederate Army of ''Northern'' Virginia ...

, elements of which were moving towards Thoroughfare Gap in Fauquier County

Fauquier is a county in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 72,972. The county seat is Warrenton.

Fauquier County is in Northern Virginia and is a part of the Washington metropolitan area.

History

In 160 ...

. Gen. Stuart and his cavalry reached Amissville on August 22, and turned back to surround Pope's army. In an attack near Catlett's Station, Gen. Stuart's men captured Gen. Pope's overcoat and military papers.

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to theKöppen Climate Classification

The Köppen climate classification is one of the most widely used climate classification systems. It was first published by German-Russian climatologist Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) in 1884, with several later modifications by Köppen, notabl ...

system, Amissville has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.

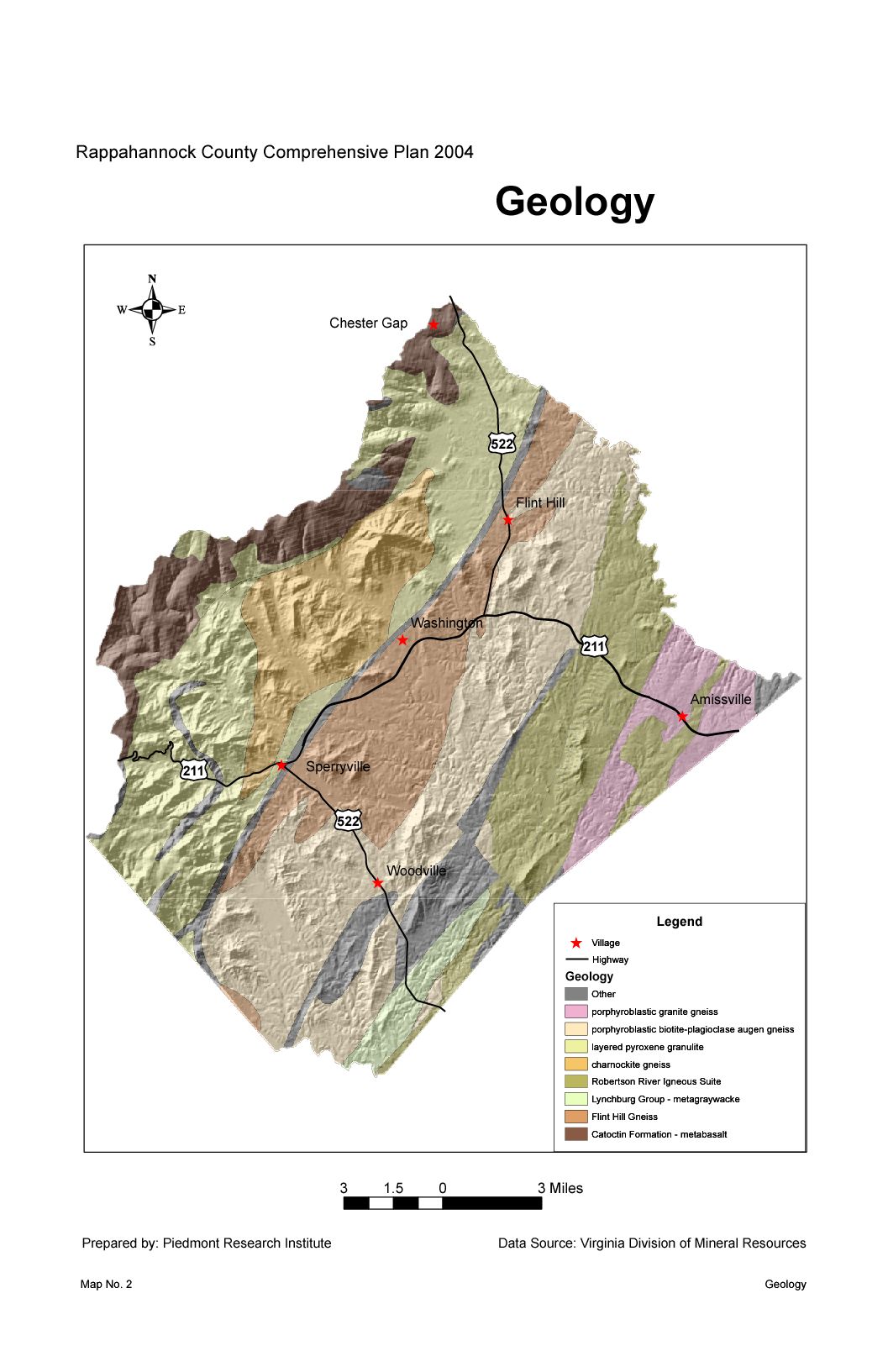

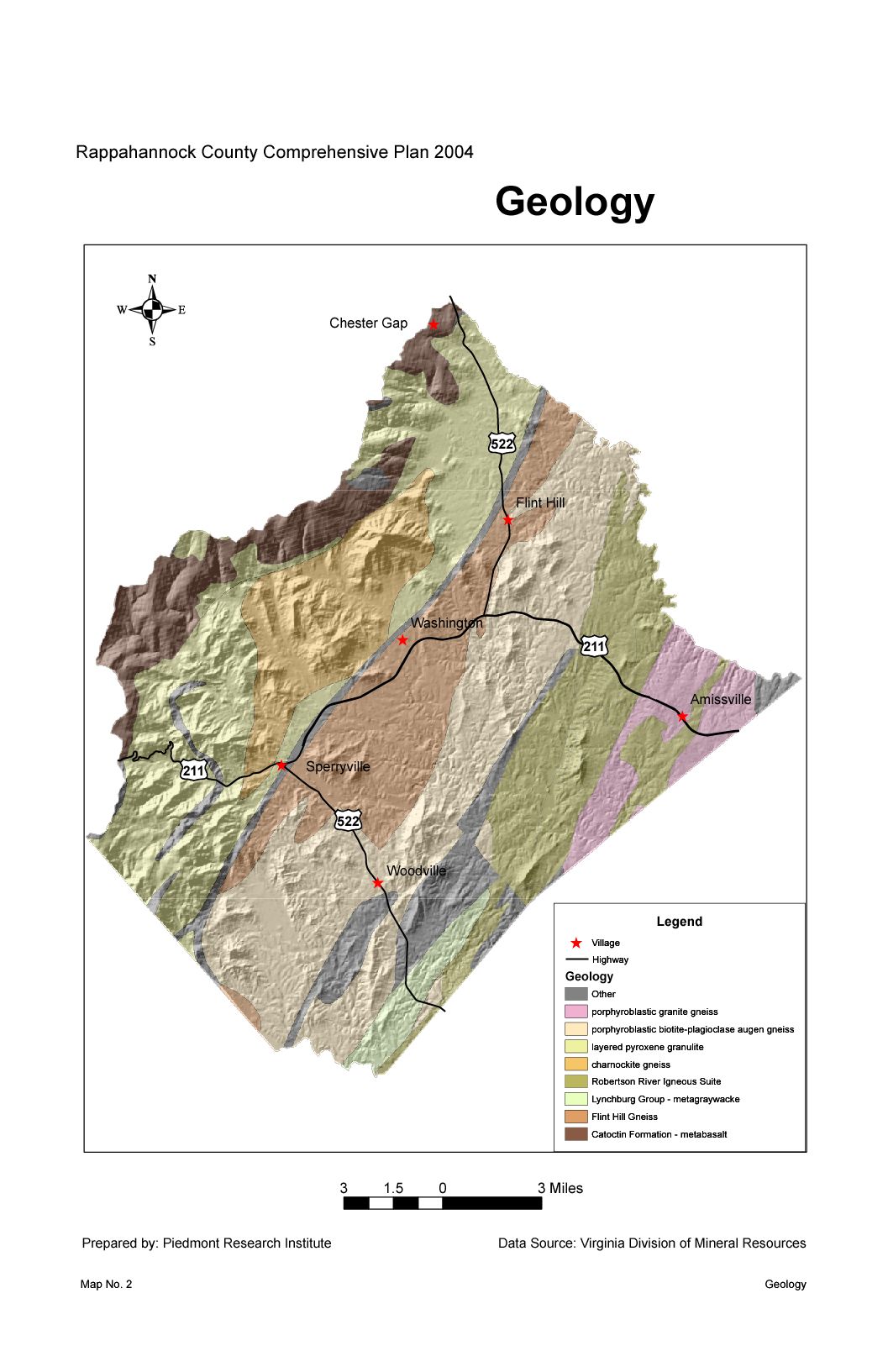

Geology

The geology of Amissville and the surrounding vicinity consists of several units. Predominant and oldest (approximately 704 million years old, +/- 5 million years, based on the U- Pb

The geology of Amissville and the surrounding vicinity consists of several units. Predominant and oldest (approximately 704 million years old, +/- 5 million years, based on the U- Pb zircon

Zircon () is a mineral belonging to the group of nesosilicates and is a source of the metal zirconium. Its chemical name is zirconium(IV) silicate, and its corresponding chemical formula is Zr SiO4. An empirical formula showing some of t ...

geochronology

Geochronology is the science of determining the age of rocks, fossils, and sediments using signatures inherent in the rocks themselves. Absolute geochronology can be accomplished through radioactive isotopes, whereas relative geochronology is ...

dating method, coinciding with the initial rifting

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart and is an example of extensional tectonics.

Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-graben wi ...

of the supercontinent

In geology, a supercontinent is the assembly of most or all of Earth's continental blocks or cratons to form a single large landmass. However, some geologists use a different definition, "a grouping of formerly dispersed continents", which leav ...

Rodinia) is the Neoproterozoic

The Neoproterozoic Era is the unit of geologic time from 1 billion to 538.8 million years ago.

It is the last era of the Precambrian Supereon and the Proterozoic Eon; it is subdivided into the Tonian, Cryogenian, and Ediacaran periods. It is prec ...

alkali feldspar granitic

A granitoid is a generic term for a diverse category of coarse-grained igneous rocks that consist predominantly of quartz, plagioclase, and alkali feldspar. Granitoids range from plagioclase-rich tonalites to alkali-rich syenites and from quartz- ...

rock of the Robertson River Igneous

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or ...

Suite. This includes felsic complex material such as biotite, hornblende

Hornblende is a complex inosilicate series of minerals. It is not a recognized mineral in its own right, but the name is used as a general or field term, to refer to a dark amphibole. Hornblende minerals are common in igneous and metamorphic rock ...

-biotite, magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With th ...

, and alkali granitic rock

Rock most often refers to:

* Rock (geology), a naturally occurring solid aggregate of minerals or mineraloids

* Rock music, a genre of popular music

Rock or Rocks may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Rock, Caerphilly, a location in Wales ...

including rhyolite on the eastern slopes of Battle Mountain and Little Battle Mountain.

Battle Mountain and Little Battle Mountain are the only mountains in Rappahannock County which are known to be volcanic

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates a ...

in origin, and are among the oldest visibly intact extinct volcanoes in Virginia. White quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica ( silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical ...

boulders

In geology, a boulder (or rarely bowlder) is a rock fragment with size greater than in diameter. Smaller pieces are called cobbles and pebbles. While a boulder may be small enough to move or roll manually, others are extremely massive.

In c ...

and smaller fragments are common on and around Battle Mountain, a result of molten silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is ...

that was contained in the rhyolite lava

Lava is molten or partially molten rock (magma) that has been expelled from the interior of a terrestrial planet (such as Earth) or a moon onto its surface. Lava may be erupted at a volcano or through a fracture in the crust, on land or un ...

and granitic magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natural sa ...

that formed the volcano.

The Robertson River Igneous Suite extends from south of Laurel Mills (originating near Charlottesville

Charlottesville, colloquially known as C'ville, is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is the county seat of Albemarle County, which surrounds the city, though the two are separate legal entities. It is named after Queen Ch ...

) and runs north-northeast through Hackleys Crossroad and beyond in a band approximately four kilometers wide. Precambrian coarse leucogneiss and fine-grained gneiss prevails from the eastern edge of the Amissville, Rappahannock County

Rappahannock County is a county located in the northern Piedmont region of the Commonwealth of Virginia, US, adjacent to Shenandoah National Park. As of the 2020 Census, the population was 7,348. Its county seat is Washington. The name "Rappah ...

area from north of the Amissville post office and U.S. Route 211 and south to Viewtown. Flint Hill Gneiss

Gneiss ( ) is a common and widely distributed type of metamorphic rock. It is formed by high-temperature and high-pressure metamorphic processes acting on formations composed of igneous or sedimentary rocks. Gneiss forms at higher temperatures a ...

, a light to dark-gray quartz monzonite

Monzonite is an igneous intrusive rock, formed by slow cooling of underground magma that has a moderate silica content and is enriched in alkali metal oxides. Monzonite is composed mostly of plagioclase and alkali feldspar.

Syenodiorite is an o ...

gneiss is predominate from Ben Venue and west to Massies Corner and extending further into Rock Mills and the town of Washington, Virginia

The town of Washington, Virginia, is a historic village located in the eastern foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains near Shenandoah National Park. The entire town is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as a historic district, Wa ...

.

A fine-grained Precambrian arkosic

Arkose () or arkosic sandstone is a detrital sedimentary rock, specifically a type of sandstone containing at least 25% feldspar.

Arkosic sand is sand that is similarly rich in feldspar, and thus the potential precursor of arkose.

Quartz is ...

sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates ...

and conglomerate, which Aaron Mountain is composed of, occurs on the contact between the Flint Hill Gneiss starting approximately two kilometers west of Laurel Mills and running north-northeast along a narrow band (starting out at approximately 1 kilometer wide and tapering down to 100 meters) in contact with the Robertson River Igneous Suite, terminating just south of U.S. Route 211. The creeksides and river bottoms of the Thorton River, Battle Run and the Rappahannock River

The Rappahannock River is a river in eastern Virginia, in the United States, approximately in length.U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 It traverses the entir ...

and their smaller tributaries

A tributary, or affluent, is a stream or river that flows into a larger stream or main stem (or parent) river or a lake. A tributary does not flow directly into a sea or ocean. Tributaries and the main stem river drain the surrounding drainag ...

are all composed of Quaternary Period

The Quaternary ( ) is the current and most recent of the three periods of the Cenozoic Era in the geologic time scale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). It follows the Neogene Period and spans from 2.58 million years ...

alluvium

Alluvium (from Latin ''alluvius'', from ''alluere'' 'to wash against') is loose clay, silt, sand, or gravel that has been deposited by running water in a stream bed, on a floodplain, in an alluvial fan or beach, or in similar settings. ...

including stratified, unconsolidated

Soil consolidation refers to the mechanical process by which soil changes volume gradually in response to a change in pressure. This happens because soil is a two-phase material, comprising soil grains and pore fluid, usually groundwater. When ...

gray to grayish-yellow sand

Sand is a granular material composed of finely divided mineral particles. Sand has various compositions but is defined by its grain size. Sand grains are smaller than gravel and coarser than silt. Sand can also refer to a textural class o ...

, silt

Silt is granular material of a size between sand and clay and composed mostly of broken grains of quartz. Silt may occur as a soil (often mixed with sand or clay) or as sediment mixed in suspension with water. Silt usually has a floury feel ...

and local gravels.

Notes

References

External links

Amissville.com

{{authority control Unincorporated communities in Rappahannock County, Virginia Unincorporated communities in Virginia Populated places established in 1810 1810 establishments in Virginia