American Equal Rights Association on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The American Equal Rights Association (AERA) was formed in 1866 in the

The American Equal Rights Association (AERA) was formed in 1866 in the

p. 168

"Mott, Lucretia Coffin" * Elizabeth Cady Stanton attended the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention as an observer, accompanying her husband Henry B. Stanton, who had worked as an agent of the American Anti-Slavery Society. There she and Mott became friends and vowed to organize a women's rights convention in the United States. Stanton was an organizer of the Seneca Falls Convention and the primary author of its Declaration of Sentiments. * Lucy Stone was a pioneering worker for women's rights and an organizer of the first National Women's Rights Convention in 1850. She became a paid representative of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1848 under an arrangement by which she could also lecture on women's rights but without pay. * Susan B. Anthony became a paid representative of the Anti-Slavery Society in 1856 with the understanding that she would also continue to campaign for women's rights. * * Abby Kelley Foster and her husband Stephen Symonds Foster were abolitionists who had encouraged Anthony to become active in the Anti-Slavery Society.

* Henry Blackwell, who was married to Lucy Stone, worked against slavery and for women's rights.

* Sojourner Truth, abolitionist and women's-rights activists

* Sarah Parker Remond, abolitionist and activist for formerly enslaved Black people

* Abby Kelley Foster and her husband Stephen Symonds Foster were abolitionists who had encouraged Anthony to become active in the Anti-Slavery Society.

* Henry Blackwell, who was married to Lucy Stone, worked against slavery and for women's rights.

* Sojourner Truth, abolitionist and women's-rights activists

* Sarah Parker Remond, abolitionist and activist for formerly enslaved Black people

After slavery in the U.S. was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, Wendell Phillips was elected president of the Anti-Slavery Society and began to direct its resources toward winning political rights for blacks. He told women's rights activists that he continued to support women's suffrage but thought it best to set aside that demand until voting rights for African American men were assured.

The women's movement began to revive when proposals for a Fourteenth Amendment began circulating that would secure citizenship (but not yet voting rights) for African Americans. Some of the proposals for this amendment would also for the first time introduce the word "male" into the Constitution, which begins with the words "We the People of the United States". Stanton said that "if that word 'male' be inserted, it will take us a century at least to get it out."

Stanton, Anthony and Lucy Stone, the most prominent figures in the women's movement, circulated a letter in late 1865 calling for petitions against any wording that excluded females.Cullen-DuPont (1998)

After slavery in the U.S. was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, Wendell Phillips was elected president of the Anti-Slavery Society and began to direct its resources toward winning political rights for blacks. He told women's rights activists that he continued to support women's suffrage but thought it best to set aside that demand until voting rights for African American men were assured.

The women's movement began to revive when proposals for a Fourteenth Amendment began circulating that would secure citizenship (but not yet voting rights) for African Americans. Some of the proposals for this amendment would also for the first time introduce the word "male" into the Constitution, which begins with the words "We the People of the United States". Stanton said that "if that word 'male' be inserted, it will take us a century at least to get it out."

Stanton, Anthony and Lucy Stone, the most prominent figures in the women's movement, circulated a letter in late 1865 calling for petitions against any wording that excluded females.Cullen-DuPont (1998)

pp. 11–12

"American Equal Rights Association" A version of the amendment that referred to "persons" instead of "males" passed the

p. 71

/ref> In a variation of the idea proposed earlier to the Anti-Slavery Society, the convention voted to transform itself into a new organization called the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) that would campaign for the rights of both women and blacks, advocating suffrage for both. The new organization elected Lucretia Mott as president and created an executive committee that included Stanton, Anthony and Lucy Stone.

The AERA launched lobbying and petition campaigns in several states, hoping to create a drive strong enough to convince the Anti-Slavery Society to accept its goal of universal suffrage rather than suffrage for black men only.

In a variation of the idea proposed earlier to the Anti-Slavery Society, the convention voted to transform itself into a new organization called the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) that would campaign for the rights of both women and blacks, advocating suffrage for both. The new organization elected Lucretia Mott as president and created an executive committee that included Stanton, Anthony and Lucy Stone.

The AERA launched lobbying and petition campaigns in several states, hoping to create a drive strong enough to convince the Anti-Slavery Society to accept its goal of universal suffrage rather than suffrage for black men only.

p. 214

/ref> Asked by

p. 219

/ref>

Greeley had earlier clashed with Anthony and Stanton by insisting that their New York campaign should focus on the rights of African Americans rather than also including women's issues. When they refused, he threatened to end his newspaper's support for their work.

Soon he began to attack the women's movement. Responding to Greeley's repeated claim that the best women he knew did not want to vote, Stanton and Anthony arranged for it to be announced from the floor of the convention that Mrs. Horace Greeley had signed the petition in favor of women's suffrage.

The '' History of Woman Suffrage'', whose authors include Stanton and Anthony, said, "This campaign cost us the friendship of Horace Greeley and the support of the '' New York Tribune'', heretofore our most powerful and faithful allies."

Greeley had earlier clashed with Anthony and Stanton by insisting that their New York campaign should focus on the rights of African Americans rather than also including women's issues. When they refused, he threatened to end his newspaper's support for their work.

Soon he began to attack the women's movement. Responding to Greeley's repeated claim that the best women he knew did not want to vote, Stanton and Anthony arranged for it to be announced from the floor of the convention that Mrs. Horace Greeley had signed the petition in favor of women's suffrage.

The '' History of Woman Suffrage'', whose authors include Stanton and Anthony, said, "This campaign cost us the friendship of Horace Greeley and the support of the '' New York Tribune'', heretofore our most powerful and faithful allies."

The willingness of Anthony and Stanton to work with Train alienated many AERA members and other reform activists. Stone said she considered Train to be "a lunatic, wild and ranting".

Anthony and Stanton angered Stone by including her name, without her permission, in a public letter praising Train.

Stone and her allies angered Anthony by charging her with misuse of funds, a charge that was later disproved,

and by blocking payment of her salary and expenses for her work in Kansas.

Opposition to Train was not due solely to his racism. Henry Blackwell, Stone's husband, had just demonstrated that even AERA workers were not automatically free from the racial presumptions of that era by publishing an open letter to Southern legislatures assuring them that if they allowed both blacks and women to vote, "the political supremacy of your white race will remain unchanged" and that "the black race would gravitate by the law of nature toward the tropics."

Opposition to Train was partly due to the loyalty many reformers felt to the national

The willingness of Anthony and Stanton to work with Train alienated many AERA members and other reform activists. Stone said she considered Train to be "a lunatic, wild and ranting".

Anthony and Stanton angered Stone by including her name, without her permission, in a public letter praising Train.

Stone and her allies angered Anthony by charging her with misuse of funds, a charge that was later disproved,

and by blocking payment of her salary and expenses for her work in Kansas.

Opposition to Train was not due solely to his racism. Henry Blackwell, Stone's husband, had just demonstrated that even AERA workers were not automatically free from the racial presumptions of that era by publishing an open letter to Southern legislatures assuring them that if they allowed both blacks and women to vote, "the political supremacy of your white race will remain unchanged" and that "the black race would gravitate by the law of nature toward the tropics."

Opposition to Train was partly due to the loyalty many reformers felt to the national

Disagreement was especially sharp over the proposed Fifteenth Amendment, which would prohibit the denial of suffrage because of race. In practice it would, theoretically at least, guarantee suffrage for virtually all males.

Anthony and Stanton opposed passage of the amendment unless it was accompanied by a Sixteenth Amendment that would guarantee suffrage for women. Otherwise, they said, it would create an "aristocracy of sex" by giving constitutional authority to the belief that men were superior to women.

Male power and privilege was at the root of society's ills, Stanton argued, and nothing should be done to strengthen it.Rakow and Kramarae eds. (2001)

Disagreement was especially sharp over the proposed Fifteenth Amendment, which would prohibit the denial of suffrage because of race. In practice it would, theoretically at least, guarantee suffrage for virtually all males.

Anthony and Stanton opposed passage of the amendment unless it was accompanied by a Sixteenth Amendment that would guarantee suffrage for women. Otherwise, they said, it would create an "aristocracy of sex" by giving constitutional authority to the belief that men were superior to women.

Male power and privilege was at the root of society's ills, Stanton argued, and nothing should be done to strengthen it.Rakow and Kramarae eds. (2001)

p. 48

/ref> Anthony and Stanton also warned that black men, who would have voting power under the amendment, were overwhelmingly opposed to women's suffrage. (They were not alone in being unsure of black male support for women's suffrage. Frederick Douglass, a strong supporter of women's suffrage, said, "The race to which I belong have not generally taken the right ground on this question.") Most AERA members supported the Fifteenth Amendment. Among prominent African American AERA members,

p. 310

/ref> Lucy Stone criticized the Republican Party also, but Frederick Douglass defended it as more supportive of suffrage for both blacks and women than the Democrats. Distressed at Stanton's and Anthony's association with George Francis Train and the hostilities it had generated, Lucretia Mott resigned as president of the AERA that same month. She said she thought it had been mistake to attempt to unite the women's and abolitionist movements, and she recommended that the AERA be disbanded.

p. 382

/ref> Frederick Douglass objected to Stanton's use of "Sambo" to represent black men in an article she had written for ''The Revolution''. The majority of the attendees supported the pending Fifteenth Amendment, but debate was contentious.

Douglass said, "I do not see how anyone can pretend that there is the same urgency in giving the ballot to woman as to the negro. With us, the matter is a question of life and death, at least in fifteen States of the Union."

Anthony replied, "Mr. Douglass talks about the wrongs of the negro; but with all the outrages that he to-day suffers, he would not exchange his sex and take the place of Elizabeth Cady Stanton."

Lucy Stone disagreed with Douglass's assertion that suffrage for blacks should have precedence, saying that "woman suffrage is more imperative than his own."

Referring to Douglass's earlier assertion that "There are no KuKlux Clans seeking the lives of women",

Stone cited state laws that gave men control over the disposition of their children, saying that children had been known to have been taken from their mothers by "Ku-Kluxers here in the North in the shape of men".Stanton, Anthony, Gage (1887)

The majority of the attendees supported the pending Fifteenth Amendment, but debate was contentious.

Douglass said, "I do not see how anyone can pretend that there is the same urgency in giving the ballot to woman as to the negro. With us, the matter is a question of life and death, at least in fifteen States of the Union."

Anthony replied, "Mr. Douglass talks about the wrongs of the negro; but with all the outrages that he to-day suffers, he would not exchange his sex and take the place of Elizabeth Cady Stanton."

Lucy Stone disagreed with Douglass's assertion that suffrage for blacks should have precedence, saying that "woman suffrage is more imperative than his own."

Referring to Douglass's earlier assertion that "There are no KuKlux Clans seeking the lives of women",

Stone cited state laws that gave men control over the disposition of their children, saying that children had been known to have been taken from their mothers by "Ku-Kluxers here in the North in the shape of men".Stanton, Anthony, Gage (1887)

p. 384

/ref> Stone supported the Fifteenth Amendment and at the same time stressed the importance of women's rights by saying, "But I thank God for that XV. Amendment, and hope that it will be adopted in every State. I will be thankful in my soul if ''any'' body can get out of the terrible pit. But I believe that the safety of the government would be more promoted by the admission of woman as an element of restoration and harmony than the negro."

pp. 121, 136

Literate Puerto Rican women were enfranchised in 1929, per Sneider, page 134. The voting rights of African Americans in southern states were enforced by the

''Susan B. Anthony: A Biography of a Singular Feminist''

New York: Ballantine Books. . * Brown, Olympia (1911).

''Acquaintances, Old and New, Among Reformers''

Milwaukee, WI: Olympia Brown (S. E. Tate Printing Company). * Buhle, Mari Jo; Buhle, Paul editors (1978)

''The Concise History of Woman Suffrage.''

University of Illinois. . * Cullen-DuPont, Kathryn (2000)

''The Encyclopedia of Women's History in America''

second edition. New York: Facts on File. . * DuBois, Ellen Carol (1978).

''Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women's Movement in America, 1848–1869.''

Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. . * DuBois, Ellen Carol (1998)

''Woman Suffrage and Women's Rights''

New York New York University Press. . * Dudden, Faye E (2011)

''Fighting Chance: The Struggle over Woman Suffrage and Black Suffrage in Reconstruction America''

New York: Oxford University Press. . * Faulkner, Carol (2011).

''Lucretia Mott's Heresy: Abolition and Women's Rights in Nineteenth-Century America''

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. . * Foner, Eric (1990)

''A Short History of Reconstruction, 1863–1877''

New York: Harper & Row. . * Giddings, Paula (1984)

''When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America''

New York: William Morrow. . * Gordon, Ann D., ed. (1997)

''The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Vol 1: In the School of Anti-Slavery, 1840 to 1866''

New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. . * Gordon, Ann D., ed. (2000)

''The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Vol 2: Against an Aristocracy of Sex, 1866 to 1873''

New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. . * Harper, Ida Husted (1899).

''The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony, Vol 1''

Indianapolis & Kansas City: The Bowen-Merrill Company. * Heinemann, Sue (1996).

''Timelines of American Women's History''

New York: Berkley. . * Humez, Jean (2003)

''Harriet Tubman: The Life and the Life Stories''

Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. . * Kerr, Andrea Moore (1992)

''Lucy Stone: Speaking Out for Equality''

New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. . * McMillen, Sally Gregory (2008)

''Seneca Falls and the Origins of the Women's Rights Movement''

New York: Oxford University Press. . * Million, Joelle (2003).

''Woman's Voice, Woman's Place: Lucy Stone and the Birth of the Woman's Rights Movement''

Westport, CT: Praeger. . * Rakow, Lana F. and Kramarae, Cheris, editors (2001)

''The Revolution in Words: Righting Women 1868–1871''

Volume 4 of ''Women's Source Library''. New York: Routledge. . * Sneider, Allison L. (2008).

''Suffragists in an Imperial Age: U.S. Expansion and the Woman Question 1870–1929''

New York: Oxford University Press. . * Stanton, Elizabeth Cady; Anthony, Susan B.; Gage, Matilda Joslyn, editors (1887)

''History of Woman Suffrage, Vol 2''

Rochester, NY: Susan B. Anthony. * Venet, Wendy Hamand (1991)

''Neither Ballots nor Bullets: Women Abolitionists and the Civil War''

Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia. .

"Manhood Suffrage"

Elizabeth Cady Stanton's six-point explanation of her opposition to the Fifteenth Amendment. It was first published in ''The Revolution'' on December 24, 1868, and is reproduced in Gordon (2000), pp. 194–199.

"Proceedings of the 1867 AERA meeting"

from the Library of Congress {{Authority control African Americans' rights organizations Civil rights organizations in the United States Feminist organizations in the United States History of voting rights in the United States Organizations established in 1866 Reconstruction Era Women's suffrage advocacy groups in the United States 1866 establishments in the United States

The American Equal Rights Association (AERA) was formed in 1866 in the

The American Equal Rights Association (AERA) was formed in 1866 in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

. According to its constitution, its purpose was "to secure Equal Rights to all American citizens, especially the right of suffrage, irrespective of race, color or sex."

Some of the more prominent reform activists of that time were members, including women and men, blacks and whites.

The AERA was created by the Eleventh National Women's Rights Convention, which transformed itself into the new organization. Leaders of the women's movement had earlier suggested the creation of a similar equal rights organization through a merger of their movement with the American Anti-Slavery Society, but that organization did not accept their proposal.

The AERA conducted two major campaigns during 1867. In New York, which was in the process of revising its state constitution, AERA workers collected petitions in support of women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to gran ...

and the removal of property requirements that discriminated specifically against black voters. In Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to ...

they campaigned for referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of ...

s that would enfranchise

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to ...

African Americans and women. In both places they encountered increasing resistance to the campaign for women's suffrage from former abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

allies who viewed it as a hindrance to the immediate goal of winning suffrage for African American men. The Kansas campaign ended in disarray and recrimination, creating divisions between those who worked primarily for the rights of African Americans and those who worked primarily for the rights of women, and also creating divisions within the women's movement itself.

The AERA continued to hold annual meetings after the failure of the Kansas campaign, but growing differences made it difficult for its members to work together. Disagreement about the proposed Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which would prohibit the denial of suffrage because of race, was especially sharp because it did not also prohibit the denial of suffrage because of sex. The acrimonious AERA meeting in 1869 signaled the end of the organization and led to the formation of two competing women's suffrage organizations. The bitter disagreements that led to the demise of the AERA continued to influence the women's movement in subsequent years.

History

Leading participants

The people who played significant roles in the AERA included some of the more prominent reform activists of that time, many of them already acquainted with one another as veterans of the anti-slavery and women's rights movements: . * Lucretia Mott, the president of the AERA, was an abolitionist who was prevented from participating in the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840 because she was a woman. She was the main attraction and one of the organizers of the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, the firstwomen's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countr ...

convention.Cullen-DuPont (1998)p. 168

"Mott, Lucretia Coffin" * Elizabeth Cady Stanton attended the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention as an observer, accompanying her husband Henry B. Stanton, who had worked as an agent of the American Anti-Slavery Society. There she and Mott became friends and vowed to organize a women's rights convention in the United States. Stanton was an organizer of the Seneca Falls Convention and the primary author of its Declaration of Sentiments. * Lucy Stone was a pioneering worker for women's rights and an organizer of the first National Women's Rights Convention in 1850. She became a paid representative of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1848 under an arrangement by which she could also lecture on women's rights but without pay. * Susan B. Anthony became a paid representative of the Anti-Slavery Society in 1856 with the understanding that she would also continue to campaign for women's rights. *

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he becam ...

was an escaped slave and abolitionist leader who played a pivotal role in the Seneca Falls women's rights convention. He and Anthony both lived in Rochester, NY, and were family friends.

*Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (September 24, 1825 – February 22, 1911) was an American abolitionist, suffragist, poet, temperance activist, teacher, public speaker, and writer. Beginning in 1845, she was one of the first African-American women to ...

the Black American poet and anti-slavery lecturer * Abby Kelley Foster and her husband Stephen Symonds Foster were abolitionists who had encouraged Anthony to become active in the Anti-Slavery Society.

* Henry Blackwell, who was married to Lucy Stone, worked against slavery and for women's rights.

* Sojourner Truth, abolitionist and women's-rights activists

* Sarah Parker Remond, abolitionist and activist for formerly enslaved Black people

* Abby Kelley Foster and her husband Stephen Symonds Foster were abolitionists who had encouraged Anthony to become active in the Anti-Slavery Society.

* Henry Blackwell, who was married to Lucy Stone, worked against slavery and for women's rights.

* Sojourner Truth, abolitionist and women's-rights activists

* Sarah Parker Remond, abolitionist and activist for formerly enslaved Black people

Background events

Although still relatively small, the women's rights movement had grown in the years before theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

, aided by the introduction of women to social activism through the abolitionist movement. The American Anti-Slavery Society, led by William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper ''The Liberator'', which he foun ...

, was particularly encouraging to those who championed women's rights.

The planning committee for the first National Women's Rights Convention in October 1850 was formed by people who were attending a convention of the Anti-Slavery Society earlier that year.

The women's movement was loosely structured during this period, with legislative campaigns and speaking tours organized by a small group of women acting on personal initiative. An informal coordinating committee organized national women's rights conventions, but there were only a few state associations and no formal national organization.

The movement largely disappeared from public notice during the Civil War (1861–1865) as women's rights activists focused their energy on the campaign against slavery. In 1863 Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony organized the Women's Loyal National League

The Women's Loyal National League, also known as the Woman's National Loyal League and other variations of that name, was formed on May 14, 1863, to campaign for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would abolish slavery. It was organized ...

, the first national women's political organization in the U.S., to campaign for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would abolish slavery.

After slavery in the U.S. was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, Wendell Phillips was elected president of the Anti-Slavery Society and began to direct its resources toward winning political rights for blacks. He told women's rights activists that he continued to support women's suffrage but thought it best to set aside that demand until voting rights for African American men were assured.

The women's movement began to revive when proposals for a Fourteenth Amendment began circulating that would secure citizenship (but not yet voting rights) for African Americans. Some of the proposals for this amendment would also for the first time introduce the word "male" into the Constitution, which begins with the words "We the People of the United States". Stanton said that "if that word 'male' be inserted, it will take us a century at least to get it out."

Stanton, Anthony and Lucy Stone, the most prominent figures in the women's movement, circulated a letter in late 1865 calling for petitions against any wording that excluded females.Cullen-DuPont (1998)

After slavery in the U.S. was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, Wendell Phillips was elected president of the Anti-Slavery Society and began to direct its resources toward winning political rights for blacks. He told women's rights activists that he continued to support women's suffrage but thought it best to set aside that demand until voting rights for African American men were assured.

The women's movement began to revive when proposals for a Fourteenth Amendment began circulating that would secure citizenship (but not yet voting rights) for African Americans. Some of the proposals for this amendment would also for the first time introduce the word "male" into the Constitution, which begins with the words "We the People of the United States". Stanton said that "if that word 'male' be inserted, it will take us a century at least to get it out."

Stanton, Anthony and Lucy Stone, the most prominent figures in the women's movement, circulated a letter in late 1865 calling for petitions against any wording that excluded females.Cullen-DuPont (1998)pp. 11–12

"American Equal Rights Association" A version of the amendment that referred to "persons" instead of "males" passed the

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

in early 1866 but failed in the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the e ...

.

The version that Congress eventually approved and sent to the states for ratification included the word "male" three times. Stanton and Anthony opposed the amendment, but Stone supported it as a step towards universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political sta ...

.

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he becam ...

denounced it because it permitted states to disenfranchise blacks if those states were willing to accept reduced representation at the federal level.

The Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868.

At a meeting of the Anti-Slavery Society in January 1866, Stone and Anthony proposed a merger of that organization with the women's rights movement to create a new organization that would advocate for the rights for African Americans and women, including suffrage for both. The proposal was blocked by Phillips, who once again argued that the key issue of the day was suffrage for African American men.

Phillips and other abolitionist leaders expected a constitutional provision of voting rights for former slaves to help preserve the North's recent victory over the slaveholding states during the Civil War. No such benefit could be expected to follow from women's suffrage, and the effort needed to mount an effective campaign for it, they believed, would endanger the chances of winning suffrage for African American men.

(Their strategy did not work as planned. Even though the Constitution was amended in 1870 to prohibit the denial of voting rights because of race, a promise that became a reality for a brief period, violence and legal maneuvers prevented most African Americans in the South from voting until the passage of the Voting Rights Act

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights movement ...

of 1965.)

Founding in 1866

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony issued the call for the Eleventh National Women's Rights Convention, the first since the Civil War began, which met on May 10, 1866, in New York City.Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (September 24, 1825 – February 22, 1911) was an American abolitionist, suffragist, poet, temperance activist, teacher, public speaker, and writer. Beginning in 1845, she was one of the first African-American women to ...

, an African American abolitionist and writer, spoke at the convention from the viewpoint of one who had to deal with issues faced by both women and black people: "You white women speak here of rights. I speak of wrongs. I, as a colored woman, have had in this country an education which has made me feel as if I were in the situation of Ishmael, my hand against every man, and every man's hand against me.""Proceedings of the Eleventh Women's Rights Convention" (1868), pp. 45–48. Quoted in Humez (2003)p. 71

/ref>

In a variation of the idea proposed earlier to the Anti-Slavery Society, the convention voted to transform itself into a new organization called the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) that would campaign for the rights of both women and blacks, advocating suffrage for both. The new organization elected Lucretia Mott as president and created an executive committee that included Stanton, Anthony and Lucy Stone.

The AERA launched lobbying and petition campaigns in several states, hoping to create a drive strong enough to convince the Anti-Slavery Society to accept its goal of universal suffrage rather than suffrage for black men only.

In a variation of the idea proposed earlier to the Anti-Slavery Society, the convention voted to transform itself into a new organization called the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) that would campaign for the rights of both women and blacks, advocating suffrage for both. The new organization elected Lucretia Mott as president and created an executive committee that included Stanton, Anthony and Lucy Stone.

The AERA launched lobbying and petition campaigns in several states, hoping to create a drive strong enough to convince the Anti-Slavery Society to accept its goal of universal suffrage rather than suffrage for black men only.

1867 annual meeting

The AERA held its first annual meeting in New York City on May 9, 1867. Referring to the growing demand for suffrage for African American men, Lucretia Mott, the AERA's president, said, "woman had a right to be a little jealous of the addition of so large a number of men to the voting class, for the colored men would naturally throw all their strength upon the side of those opposed to woman's enfranchisement."Stanton, Anthony, Gage (1887)p. 214

/ref> Asked by

George T. Downing

George T. Downing (December 30, 1819 – July 21, 1903) was an abolitionist and activist for African-American civil rights while building a successful career as a restaurateur in New York City; Newport, Rhode Island; and Washington, D.C. His fath ...

, an African American, whether she would be willing for the black man to have the vote before woman, Elizabeth Cady Stanton replied, "I would say, no; I would not trust him with all my rights; degraded, oppressed himself, he would be more despotic with the governing power than even our Saxon rulers are. I desire that we go into the kingdom together".

Sojourner Truth, a former slave, said that, "if colored men get their rights, and not colored women theirs, you see the colored men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before."

Others disagreed. Abby Kelley Foster said that suffrage for black men was a more pressing issue than suffrage for women.

Stephen Symonds Foster, arguing that ballot rights for one group of citizens should not be contingent on ballot rights for another, said, "The right of each should be accorded at the earliest possible moment, neither being denied for any supposed benefit to the other."

Henry Ward Beecher

Henry Ward Beecher (June 24, 1813 – March 8, 1887) was an American Congregationalist clergyman, social reformer, and speaker, known for his support of the abolition of slavery, his emphasis on God's love, and his 1875 adultery trial. His r ...

, a prominent minister, said he was in favor of universal suffrage but believed that by demanding the vote for both blacks and women, the movement was likely to achieve at least a partial victory by winning the vote for black men.Stanton, Anthony, Gage (1887)p. 219

/ref>

New York campaign

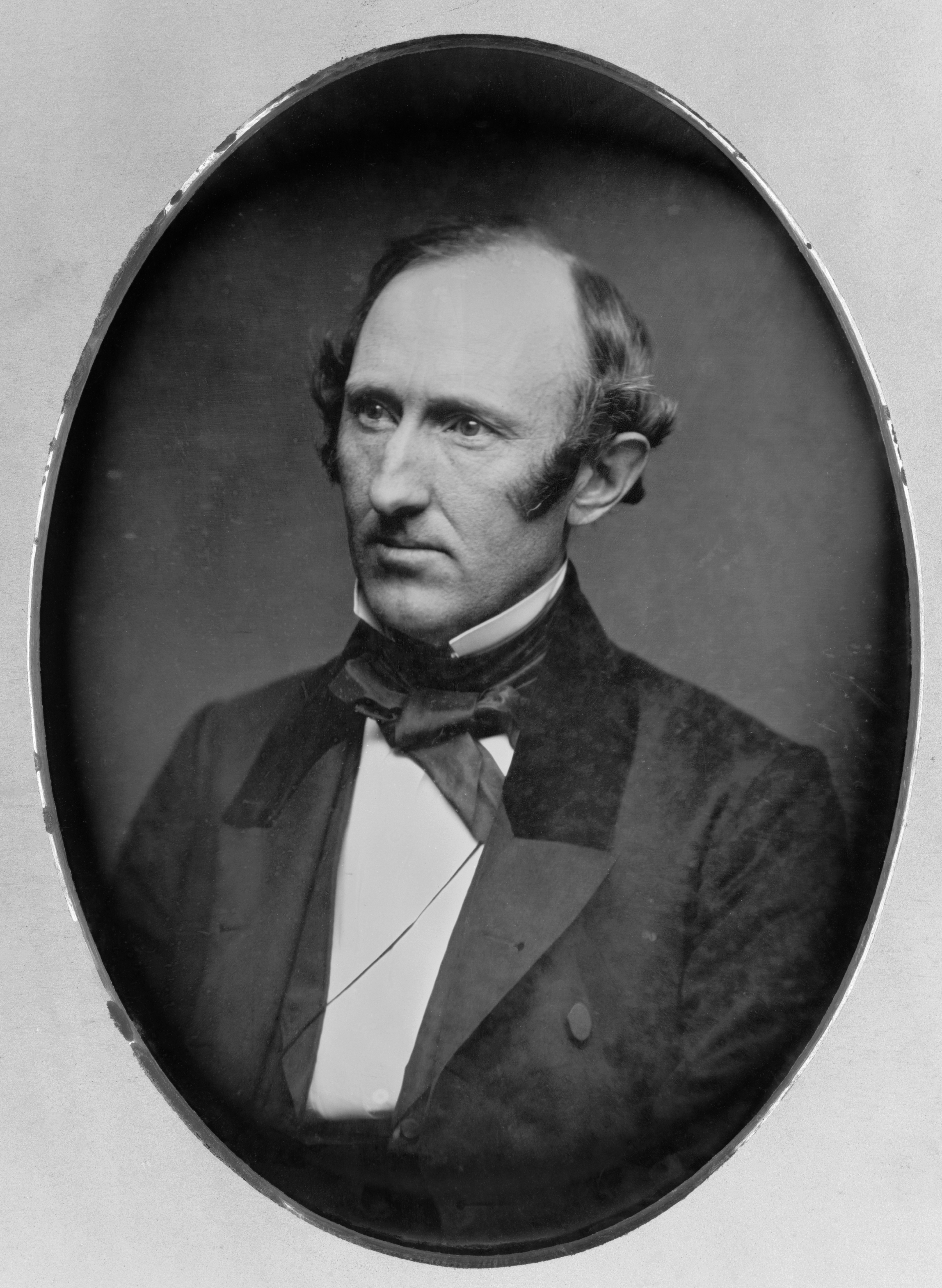

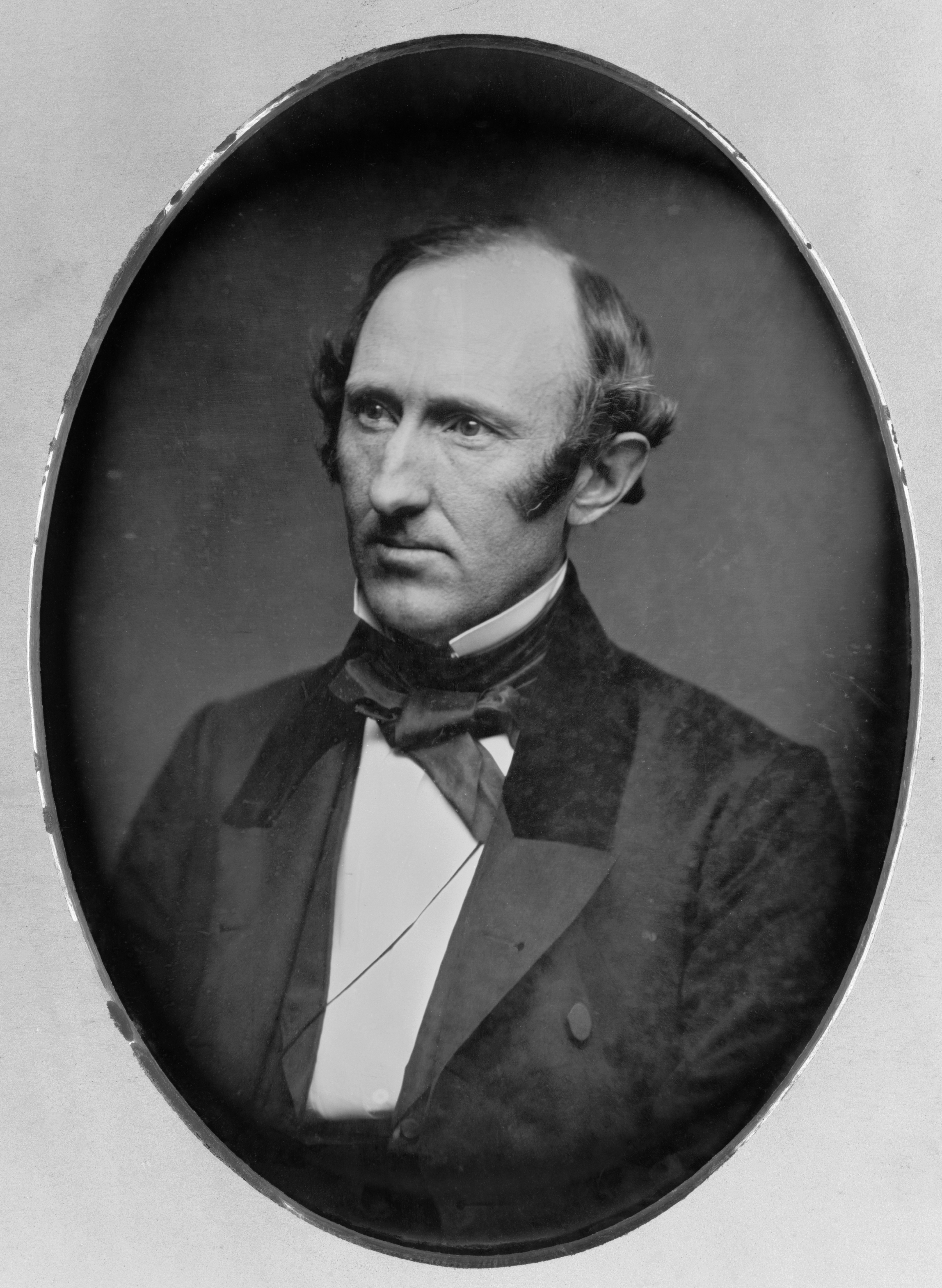

The state of New York organized a convention in June 1867 to revise its constitution. AERA workers prepared for it by organizing meetings in over 30 locations around the state and collecting over 20,000 signatures on petitions that supported women's suffrage and the removal of property requirements that discriminated specifically against black voters.DuBois (1978), p. 87 The suffrage committee of the convention was chaired byHorace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and editor of the '' New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressman from New York, ...

, a prominent newspaper editor and abolitionist who had been a supporter of the women's movement. His committee approved the removal of discriminatory property requirements for black voters but rejected the proposal for women's suffrage.

Greeley had earlier clashed with Anthony and Stanton by insisting that their New York campaign should focus on the rights of African Americans rather than also including women's issues. When they refused, he threatened to end his newspaper's support for their work.

Soon he began to attack the women's movement. Responding to Greeley's repeated claim that the best women he knew did not want to vote, Stanton and Anthony arranged for it to be announced from the floor of the convention that Mrs. Horace Greeley had signed the petition in favor of women's suffrage.

The '' History of Woman Suffrage'', whose authors include Stanton and Anthony, said, "This campaign cost us the friendship of Horace Greeley and the support of the '' New York Tribune'', heretofore our most powerful and faithful allies."

Greeley had earlier clashed with Anthony and Stanton by insisting that their New York campaign should focus on the rights of African Americans rather than also including women's issues. When they refused, he threatened to end his newspaper's support for their work.

Soon he began to attack the women's movement. Responding to Greeley's repeated claim that the best women he knew did not want to vote, Stanton and Anthony arranged for it to be announced from the floor of the convention that Mrs. Horace Greeley had signed the petition in favor of women's suffrage.

The '' History of Woman Suffrage'', whose authors include Stanton and Anthony, said, "This campaign cost us the friendship of Horace Greeley and the support of the '' New York Tribune'', heretofore our most powerful and faithful allies."

Kansas campaign

Tworeferendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of ...

s were placed before voters in Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to ...

in 1867, one that would extend suffrage to black men and one that would extend it to women. Kansas had an anti-slavery heritage and the strongest laws for the protection of women's rights outside New York. The AERA concentrated its resources on this campaign with high hopes of winning both referendums, which would boost the chances of winning suffrage for both blacks and woman at the national level. Both referendums failed, however, and the AERA campaign ended in disarray and recrimination. The Kansas campaign created divisions between those who worked primarily for the rights of African Americans and those who worked primarily for the rights of women, and it also created divisions within the women's movement itself.

The New York campaign had been financed partly by the Hovey Fund

The Hovey Fund was created by a bequest from Charles Fox Hovey (1807-1859), a Boston merchant who supported a variety of social reform movements. Hovey left $50,000 to support abolitionism and other types of social reform, including "women's right ...

, which was created by a bequest that provided a large sum of money to support abolitionism, women's rights and other reform movements.

According to the terms of the bequest, if slavery was abolished, the remainder of the money was to go to the other reform movements, which meant that the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment should have freed up a significant stream of money for the women's movement. However, Wendell Phillips, the head of the fund, declared that slavery would not truly be abolished until blacks were enfranchised on the same basis as whites, and he channeled much of fund's money toward that cause.

The AERA nonetheless expected the Hovey Fund to support its Kansas campaign, which worked for the enfranchisement of both African Americans and women. The fund refused to finance the Kansas campaign, however, because Phillips opposed mixing those two causes, leaving the campaign desperately short of money.

It was difficult for the women's movement itself to raise enough money for projects like this because few women had independent sources of income, and even those with employment generally were required by law to turn over their pay to their husbands.

The AERA's Kansas campaign began when Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell arrived in April.

The AERA workers were disconcerted when, after an internal struggle, Kansas Republicans decided to support suffrage for black men only, not merely refusing to support women's suffrage but forming an "Anti Female Suffrage Committee" to organize opposition to those who were campaigning for it.

In a letter to Anthony, Stone wrote, "But the negroes are all against us. There has just now left us an ignorant black preacher named Twine, who is very confident that women ought not to vote. These men ought not to be allowed to vote before we do, because they will be just so much more dead weight to lift."

By the end of summer the AERA campaign had almost collapsed under the weight of Republican hostility, and its finances were exhausted.

Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton arrived in September to work on the campaign. They created a storm of controversy by accepting help during the last two and a half weeks of the campaign from George Francis Train

George Francis Train (March 24, 1829 – January 18, 1904) was an American entrepreneur who organized the clipper ship line that sailed around Cape Horn to San Francisco; he also organized the Union Pacific Railroad and the Credit Mobilier in th ...

, a Democrat, a wealthy businessman and a flamboyant speaker who supported women's rights.

Train was a political maverick who had attended the Democratic convention during the presidential election year of 1864 but then campaigned vigorously for the Republican candidate, Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

. By 1867 he was promoting himself as an independent candidate for president.

Train was also a racist who openly disparaged the integrity and intelligence of African Americans, supporting women's suffrage partly in the belief that the votes of women would help contain the political power of blacks.

The usual procedure was for Anthony to speak first, declaring that the ability to vote rightfully belonged to both women and blacks. Train would speak next, declaring that it would be an outrage for blacks to vote but not women also.

The willingness of Anthony and Stanton to work with Train alienated many AERA members and other reform activists. Stone said she considered Train to be "a lunatic, wild and ranting".

Anthony and Stanton angered Stone by including her name, without her permission, in a public letter praising Train.

Stone and her allies angered Anthony by charging her with misuse of funds, a charge that was later disproved,

and by blocking payment of her salary and expenses for her work in Kansas.

Opposition to Train was not due solely to his racism. Henry Blackwell, Stone's husband, had just demonstrated that even AERA workers were not automatically free from the racial presumptions of that era by publishing an open letter to Southern legislatures assuring them that if they allowed both blacks and women to vote, "the political supremacy of your white race will remain unchanged" and that "the black race would gravitate by the law of nature toward the tropics."

Opposition to Train was partly due to the loyalty many reformers felt to the national

The willingness of Anthony and Stanton to work with Train alienated many AERA members and other reform activists. Stone said she considered Train to be "a lunatic, wild and ranting".

Anthony and Stanton angered Stone by including her name, without her permission, in a public letter praising Train.

Stone and her allies angered Anthony by charging her with misuse of funds, a charge that was later disproved,

and by blocking payment of her salary and expenses for her work in Kansas.

Opposition to Train was not due solely to his racism. Henry Blackwell, Stone's husband, had just demonstrated that even AERA workers were not automatically free from the racial presumptions of that era by publishing an open letter to Southern legislatures assuring them that if they allowed both blacks and women to vote, "the political supremacy of your white race will remain unchanged" and that "the black race would gravitate by the law of nature toward the tropics."

Opposition to Train was partly due to the loyalty many reformers felt to the national Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

*Republican Party (Liberia)

* Republican Part ...

, which had provided political leadership for the elimination of slavery and was still in the difficult process of consolidating that victory. Train harshly attacked the Republican Party, making no secret of his desire to blemish its progressive image and create splits within it by campaigning for women's rights when Kansas Republicans were refusing to do so.

The abolitionist movement was sensitive to attacks on the Republican Party, with which it collaborated closely, serving in some ways as its left wing.

The women's rights movement depended heavily on abolitionist resources, with its articles published in their newspapers and some of its funding provided by abolitionists.

After the Kansas debacle, women's suffragists who distanced themselves from abolitionist and Republican leadership found those resources increasingly unavailable. Wendell Phillips worked to prevent discussion of women's suffrage at abolitionist meetings, and abolitionist journals began to downplay those issues as well.

The '' History of Woman Suffrage'' stated the conclusions drawn by the wing of the movement associated with Anthony and Stanton: "Our liberal men counseled us to silence during the war, and we were silent on our own wrongs; they counseled us again to silence in Kansas and New York, lest we should defeat 'negro suffrage,' and threatened if we were not, we might fight the battle alone. We chose the latter, and were defeated. But standing alone we learned our power... woman must lead the way to her own enfranchisement."

Disagreement and division

After the Kansas campaign ended in disarray in November 1867, the AERA increasingly divided into two wings, both advocating universal suffrage but with different approaches. One wing, whose leading figure was Lucy Stone, was willing for black men to achieve suffrage first and wanted to maintain close ties with the Republican Party and the abolitionist movement. The other, whose leading figures were Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, insisted that women and black men should be enfranchised at the same time and worked toward a politically independent women's movement that would no longer be dependent on abolitionists. Stanton and Anthony expressed their views in a newspaper called ''The Revolution

A revolution is a drastic political change that usually occurs relatively quickly. For revolutions which affect society, culture, and technology more than political systems, see social revolution.

Revolution may also refer to:

Aviation

*Warner ...

'', which began publishing in January 1868 with initial funding from the controversial George Francis Train

George Francis Train (March 24, 1829 – January 18, 1904) was an American entrepreneur who organized the clipper ship line that sailed around Cape Horn to San Francisco; he also organized the Union Pacific Railroad and the Credit Mobilier in th ...

.

Disagreement was especially sharp over the proposed Fifteenth Amendment, which would prohibit the denial of suffrage because of race. In practice it would, theoretically at least, guarantee suffrage for virtually all males.

Anthony and Stanton opposed passage of the amendment unless it was accompanied by a Sixteenth Amendment that would guarantee suffrage for women. Otherwise, they said, it would create an "aristocracy of sex" by giving constitutional authority to the belief that men were superior to women.

Male power and privilege was at the root of society's ills, Stanton argued, and nothing should be done to strengthen it.Rakow and Kramarae eds. (2001)

Disagreement was especially sharp over the proposed Fifteenth Amendment, which would prohibit the denial of suffrage because of race. In practice it would, theoretically at least, guarantee suffrage for virtually all males.

Anthony and Stanton opposed passage of the amendment unless it was accompanied by a Sixteenth Amendment that would guarantee suffrage for women. Otherwise, they said, it would create an "aristocracy of sex" by giving constitutional authority to the belief that men were superior to women.

Male power and privilege was at the root of society's ills, Stanton argued, and nothing should be done to strengthen it.Rakow and Kramarae eds. (2001)p. 48

/ref> Anthony and Stanton also warned that black men, who would have voting power under the amendment, were overwhelmingly opposed to women's suffrage. (They were not alone in being unsure of black male support for women's suffrage. Frederick Douglass, a strong supporter of women's suffrage, said, "The race to which I belong have not generally taken the right ground on this question.") Most AERA members supported the Fifteenth Amendment. Among prominent African American AERA members,

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (September 24, 1825 – February 22, 1911) was an American abolitionist, suffragist, poet, temperance activist, teacher, public speaker, and writer. Beginning in 1845, she was one of the first African-American women to ...

, Frederick Douglass, George Downing and Dr. Charles Purvis supported the amendment, but Dr. Purvis' father, Robert Purvis, joined Anthony and Stanton in opposition to it.

Congress approved the Fifteenth Amendment in February 1869, and it was ratified by the states a year later.

During the debate over the Fifteenth Amendment, Stanton wrote articles for ''The Revolution'' with language that was sometimes elitist and racially condescending.

She believed that a long process of education would be needed before what she called the "lower orders" of former slaves and immigrant workers would be able to participate meaningfully as voters.

Stanton wrote, "American women of wealth, education, virtue and refinement, if you do not wish the lower orders of Chinese, Africans, Germans and Irish, with their low ideas of womanhood to make laws for you and your daughters ... demand that women too shall be represented in government."

After first saying in another article, "There is only one safe, sure way to build a government, and that is on the equality of all its citizens, male and female, black and white",

Stanton then objected to laws being made for women by "Patrick and Sambo and Hans and Yung Tung who do not know the difference between a Monarchy and a Republic".

Anthony and Stanton also attacked the Republican Party and worked to develop connections with the Democrats. They wrote a letter to the 1868 Democratic National Convention that criticized Republican sponsorship of the Fourteenth Amendment (which granted citizenship to black men but introduced the word "male" into the Constitution), saying, "While the dominant party has with one hand lifted up two million black men and crowned them with the honor and dignity of citizenship, with the other it has dethroned fifteen million white women—their own mothers and sisters, their own wives and daughters—and cast them under the heel of the lowest orders of manhood."

They urged liberal Democrats to convince their party, which did not have a clear direction at that point, to embrace universal suffrage.

Their attempt to collaborate with Democrats did not go far, however, because their politics were too pro-black for the Democratic Party of that era.

Despite the growing number of Democratic leaders who advocated the acceptance of black political power in the South, Southern Democrats had already begun the process of re-establishing white supremacy there, including violent suppression of the voting rights of blacks.

Several AERA members expressed anger and dismay over the activities of Stanton and Anthony during this period, including their deal with Train that gave him space to express his views in ''The Revolution''.

Some, including Lucretia Mott, president of the organization, and African Americans Frederick Douglass and Frances Harper, voiced their disagreements with Stanton and Anthony but continued to maintain working relationships with them.

Particularly in the case of Lucy Stone, however, the disputes of this period led to a personal rift, one that had important consequences for the women's movement.

To counter the initiatives of Anthony and Stanton, a planning committee was formed in May 1868 to organize a pro-Republican women's suffrage organization in the Boston area that would support the proposal to enfranchise black males first. The New England Woman Suffrage Association was subsequently founded in November 1868. Several participants in new organization were also active in the AERA, including Lucy Stone, Frederick Douglass and the Fosters. Prominent Republican politicians were involved in the founding meeting, including a U.S. senator who was seated on the platform.

Francis Bird, a leading Massachusetts Republican, said at the meeting, "Negro suffrage, being a paramount question, would have to be settled before woman suffrage could receive the attention it deserved."

Julia Ward Howe

Julia Ward Howe (; May 27, 1819 – October 17, 1910) was an American author and poet, known for writing the " Battle Hymn of the Republic" and the original 1870 pacifist Mother's Day Proclamation. She was also an advocate for abolitionism ...

, who was elected president of the new organization, said she would not demand suffrage for women until it was achieved for blacks.

1868 annual meeting

The AERA accomplished little during 1868 except hold its annual meeting on May 14, which was marked by hostilities. At that meeting,Olympia Brown

Olympia Brown (January 5, 1835 – October 23, 1926) was an American minister and suffragist. She was the first woman to be ordained as clergy with the consent of her denomination. Brown was also an articulate advocate for women's rights and one ...

denounced the Kansas Republicans for opposing women's suffrage and stressed the need for a party that would support universal suffrage.Stanton, Anthony, Gage (1887)p. 310

/ref> Lucy Stone criticized the Republican Party also, but Frederick Douglass defended it as more supportive of suffrage for both blacks and women than the Democrats. Distressed at Stanton's and Anthony's association with George Francis Train and the hostilities it had generated, Lucretia Mott resigned as president of the AERA that same month. She said she thought it had been mistake to attempt to unite the women's and abolitionist movements, and she recommended that the AERA be disbanded.

1869 annual meeting

At the climactic AERA annual meeting on May 12, 1869, Stephen Symonds Foster objected to the renomination of Stanton and Anthony as officers. He denounced their willingness to associate with Train despite his disparagement of blacks, and he charged them with advocating "Educated Suffrage", thereby repudiating the AERA's principle of universal suffrage. Henry Blackwell responded, "Miss Anthony and Mrs. Stanton believe in the right of the negro to vote. We are united on that point. There is no question of principle between us."Stanton, Anthony, Gage (1887)p. 382

/ref> Frederick Douglass objected to Stanton's use of "Sambo" to represent black men in an article she had written for ''The Revolution''.

The majority of the attendees supported the pending Fifteenth Amendment, but debate was contentious.

Douglass said, "I do not see how anyone can pretend that there is the same urgency in giving the ballot to woman as to the negro. With us, the matter is a question of life and death, at least in fifteen States of the Union."

Anthony replied, "Mr. Douglass talks about the wrongs of the negro; but with all the outrages that he to-day suffers, he would not exchange his sex and take the place of Elizabeth Cady Stanton."

Lucy Stone disagreed with Douglass's assertion that suffrage for blacks should have precedence, saying that "woman suffrage is more imperative than his own."

Referring to Douglass's earlier assertion that "There are no KuKlux Clans seeking the lives of women",

Stone cited state laws that gave men control over the disposition of their children, saying that children had been known to have been taken from their mothers by "Ku-Kluxers here in the North in the shape of men".Stanton, Anthony, Gage (1887)

The majority of the attendees supported the pending Fifteenth Amendment, but debate was contentious.

Douglass said, "I do not see how anyone can pretend that there is the same urgency in giving the ballot to woman as to the negro. With us, the matter is a question of life and death, at least in fifteen States of the Union."

Anthony replied, "Mr. Douglass talks about the wrongs of the negro; but with all the outrages that he to-day suffers, he would not exchange his sex and take the place of Elizabeth Cady Stanton."

Lucy Stone disagreed with Douglass's assertion that suffrage for blacks should have precedence, saying that "woman suffrage is more imperative than his own."

Referring to Douglass's earlier assertion that "There are no KuKlux Clans seeking the lives of women",

Stone cited state laws that gave men control over the disposition of their children, saying that children had been known to have been taken from their mothers by "Ku-Kluxers here in the North in the shape of men".Stanton, Anthony, Gage (1887)p. 384

/ref> Stone supported the Fifteenth Amendment and at the same time stressed the importance of women's rights by saying, "But I thank God for that XV. Amendment, and hope that it will be adopted in every State. I will be thankful in my soul if ''any'' body can get out of the terrible pit. But I believe that the safety of the government would be more promoted by the admission of woman as an element of restoration and harmony than the negro."

Demise and aftermath

The acrimonious 1869 meeting signaled the effective demise of the American Equal Rights Association, which held no further annual meetings. (Its existence formally ended a year later on May 14, 1870.) Two competing woman suffrage organizations were created in its aftermath. Two days after the 1869 meeting, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton led the formation of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). In November 1869, Lucy Stone,Julia Ward Howe

Julia Ward Howe (; May 27, 1819 – October 17, 1910) was an American author and poet, known for writing the " Battle Hymn of the Republic" and the original 1870 pacifist Mother's Day Proclamation. She was also an advocate for abolitionism ...

and others formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA).

Attitudes toward the Fifteenth Amendment formed a key distinction between these two organizations, but there were other differences as well. The NWSA took a stance of political independence, but the AWSA at least initially maintained close ties with the Republican Party, expecting the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to open the way for a Republican push for women's suffrage. (That did not happen; the high point of Republican support was a non-committal reference to women's suffrage in the 1872 Republican platform.)

The NWSA worked on a wider range of women's issues than the AWSA, which criticized its rival for mixing women's suffrage with issues like divorce reform and equal pay for women.

Almost all members of the NWSA were women, as were all of its officers, but the AWSA actively sought male support and included men among its officers.

Stanton and Anthony, the leading figures in the NWSA, were more widely known as leaders of the women's suffrage movement during this period and were more influential in setting its direction.

Events soon removed the basis for two key differences of principle between the competing women's organizations. In 1870 debate about the Fifteenth Amendment was made irrelevant when that amendment was officially ratified. In 1872 disgust with corruption in government led to a mass defection of abolitionists and other social reformers from the Republicans to the short-lived Liberal Republican Party. Despite these events, the rivalry between the two women's groups was so bitter that a merger proved to be impossible for twenty years.

Ellen Carol DuBois, a historian of the women's suffrage movement, says this rivalry had far-reaching consequences for the women's movement: "More than a century has passed, and still historians become partisans in the hostilities that their opposition created."

In 1890 the NWSA and the AWSA combined to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the Nationa ...

(NAWSA), with Stanton, Anthony and Stone as its top officers.

Anthony was the key force in the new organization.

Stone, nominally the chair of its executive committee, in practice was involved only peripherally.

Women's suffrage, a key goal of the AERA, was achieved in 1920 with the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, popularly known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment.

Despite the passage of the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments, the AERA's goal of securing equal rights for all citizens, especially suffrage, still had not yet been fully achieved. Although Puerto Ricans were by law citizens of the United States, Puerto Rican women were prevented from voting until 1929, and African Americans in southern states were for the most part prevented from voting until 1965, nearly a hundred years after the AERA was formed.Sneider (2008pp. 121, 136

Literate Puerto Rican women were enfranchised in 1929, per Sneider, page 134. The voting rights of African Americans in southern states were enforced by the

Voting Rights Act

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights movement ...

of 1965.

See also

* History of women's suffrage in the United States * List of African-American abolitionists * List of major women's suffrage organizations *List of suffragists and suffragettes

This list of suffragists and suffragettes includes noted individuals active in the worldwide women's suffrage movement who have campaigned or strongly advocated for women's suffrage, the organisations which they formed or joined, and the public ...

* List of women's rights activists

* List of women's rights organizations

* Reconstruction era

* Timeline of women's rights (other than voting)

* Timeline of women's suffrage

*Voting rights in the United States

Voting rights in the United States, specifically the enfranchisement and disenfranchisement of different groups, has been a moral and political issue throughout United States history.

Eligibility to vote in the United States is governed b ...

References

Notes

Bibliography

* Baker, Paula (1990). "The Domestication of Politics: Women and American Political Society, 1780–1920." In ''Unequal Sisters: A Multicultural Reader in U.S. Women's History'', Ellen Carol DuBois and Vicki L. Ruiz editors, 66–91. New York: Routledge. * Barry, Kathleen (1988)''Susan B. Anthony: A Biography of a Singular Feminist''

New York: Ballantine Books. . * Brown, Olympia (1911).

''Acquaintances, Old and New, Among Reformers''

Milwaukee, WI: Olympia Brown (S. E. Tate Printing Company). * Buhle, Mari Jo; Buhle, Paul editors (1978)

''The Concise History of Woman Suffrage.''

University of Illinois. . * Cullen-DuPont, Kathryn (2000)

''The Encyclopedia of Women's History in America''

second edition. New York: Facts on File. . * DuBois, Ellen Carol (1978).

''Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women's Movement in America, 1848–1869.''

Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. . * DuBois, Ellen Carol (1998)

''Woman Suffrage and Women's Rights''

New York New York University Press. . * Dudden, Faye E (2011)

''Fighting Chance: The Struggle over Woman Suffrage and Black Suffrage in Reconstruction America''

New York: Oxford University Press. . * Faulkner, Carol (2011).

''Lucretia Mott's Heresy: Abolition and Women's Rights in Nineteenth-Century America''

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. . * Foner, Eric (1990)

''A Short History of Reconstruction, 1863–1877''

New York: Harper & Row. . * Giddings, Paula (1984)

''When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America''

New York: William Morrow. . * Gordon, Ann D., ed. (1997)

''The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Vol 1: In the School of Anti-Slavery, 1840 to 1866''

New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. . * Gordon, Ann D., ed. (2000)

''The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Vol 2: Against an Aristocracy of Sex, 1866 to 1873''

New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. . * Harper, Ida Husted (1899).

''The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony, Vol 1''

Indianapolis & Kansas City: The Bowen-Merrill Company. * Heinemann, Sue (1996).

''Timelines of American Women's History''

New York: Berkley. . * Humez, Jean (2003)

''Harriet Tubman: The Life and the Life Stories''

Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. . * Kerr, Andrea Moore (1992)

''Lucy Stone: Speaking Out for Equality''

New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. . * McMillen, Sally Gregory (2008)

''Seneca Falls and the Origins of the Women's Rights Movement''

New York: Oxford University Press. . * Million, Joelle (2003).

''Woman's Voice, Woman's Place: Lucy Stone and the Birth of the Woman's Rights Movement''

Westport, CT: Praeger. . * Rakow, Lana F. and Kramarae, Cheris, editors (2001)

''The Revolution in Words: Righting Women 1868–1871''

Volume 4 of ''Women's Source Library''. New York: Routledge. . * Sneider, Allison L. (2008).

''Suffragists in an Imperial Age: U.S. Expansion and the Woman Question 1870–1929''

New York: Oxford University Press. . * Stanton, Elizabeth Cady; Anthony, Susan B.; Gage, Matilda Joslyn, editors (1887)

''History of Woman Suffrage, Vol 2''

Rochester, NY: Susan B. Anthony. * Venet, Wendy Hamand (1991)

''Neither Ballots nor Bullets: Women Abolitionists and the Civil War''

Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia. .

External links

"Manhood Suffrage"

Elizabeth Cady Stanton's six-point explanation of her opposition to the Fifteenth Amendment. It was first published in ''The Revolution'' on December 24, 1868, and is reproduced in Gordon (2000), pp. 194–199.

"Proceedings of the 1867 AERA meeting"

from the Library of Congress {{Authority control African Americans' rights organizations Civil rights organizations in the United States Feminist organizations in the United States History of voting rights in the United States Organizations established in 1866 Reconstruction Era Women's suffrage advocacy groups in the United States 1866 establishments in the United States