America (yacht) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''America'' was a 19th-century racing

A syndicate of New York Yacht Club members, headed by NYYC charter member Commodore John Cox Stevens, with members

A syndicate of New York Yacht Club members, headed by NYYC charter member Commodore John Cox Stevens, with members

''America'' was designed by James Rich Steers and George Steers (1820–1856) (See George Steers and Co). Traditional "cod-head-and-mackerel-tail" design gave boats a blunt bow and a sharp stern with the widest point (the beam) placed one-third of the length aft of the bow. George Steers' pilot boat designs, however, had a concave clipper-bow with the beam of the vessel at midships. She was designed along the lines of the pilot boat ''Mary Taylor''. As a result, his

''America'' was designed by James Rich Steers and George Steers (1820–1856) (See George Steers and Co). Traditional "cod-head-and-mackerel-tail" design gave boats a blunt bow and a sharp stern with the widest point (the beam) placed one-third of the length aft of the bow. George Steers' pilot boat designs, however, had a concave clipper-bow with the beam of the vessel at midships. She was designed along the lines of the pilot boat ''Mary Taylor''. As a result, his

Crewed by Brown and eight professional sailors, with George Steers, his older brother James, and James' son George as passengers, ''America'' left New York on June 21, 1851, and arrived at

Crewed by Brown and eight professional sailors, with George Steers, his older brother James, and James' son George as passengers, ''America'' left New York on June 21, 1851, and arrived at

''America'' remained in the Navy until 1873, when she was sold to Benjamin Butler for $5,000. Butler hired

''America'' remained in the Navy until 1873, when she was sold to Benjamin Butler for $5,000. Butler hired

yacht

A yacht is a sailing or power vessel used for pleasure, cruising, or racing. There is no standard definition, though the term generally applies to vessels with a cabin intended for overnight use. To be termed a , as opposed to a , such a pleasu ...

and first winner of the America's Cup

The America's Cup, informally known as the Auld Mug, is a trophy awarded in the sport of sailing. It is the oldest international competition still operating in any sport. America's Cup match races are held between two sailing yachts: one ...

international sailing trophy.

On August 22, 1851, ''America'' won the Royal Yacht Squadron's regatta around the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a Counties of England, county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the List of islands of England#Largest islands, largest and List of islands of England#Mo ...

by 18 minutes. The Squadron's "One Hundred Sovereign Cup" or "£100 Cup", sometimes mistakenly known in America as the "One Hundred Guinea Cup," was later renamed after the original winning yacht.

''America's'' origins

A syndicate of New York Yacht Club members, headed by NYYC charter member Commodore John Cox Stevens, with members

A syndicate of New York Yacht Club members, headed by NYYC charter member Commodore John Cox Stevens, with members Edwin A. Stevens

Edwin Augustus Stevens (July 28, 1795 – August 7, 1868) was an American engineer, inventor, and entrepreneur who left a bequest that was used to establish the Stevens Institute of Technology.

Life

Stevens was born at Castle Point, Hobo ...

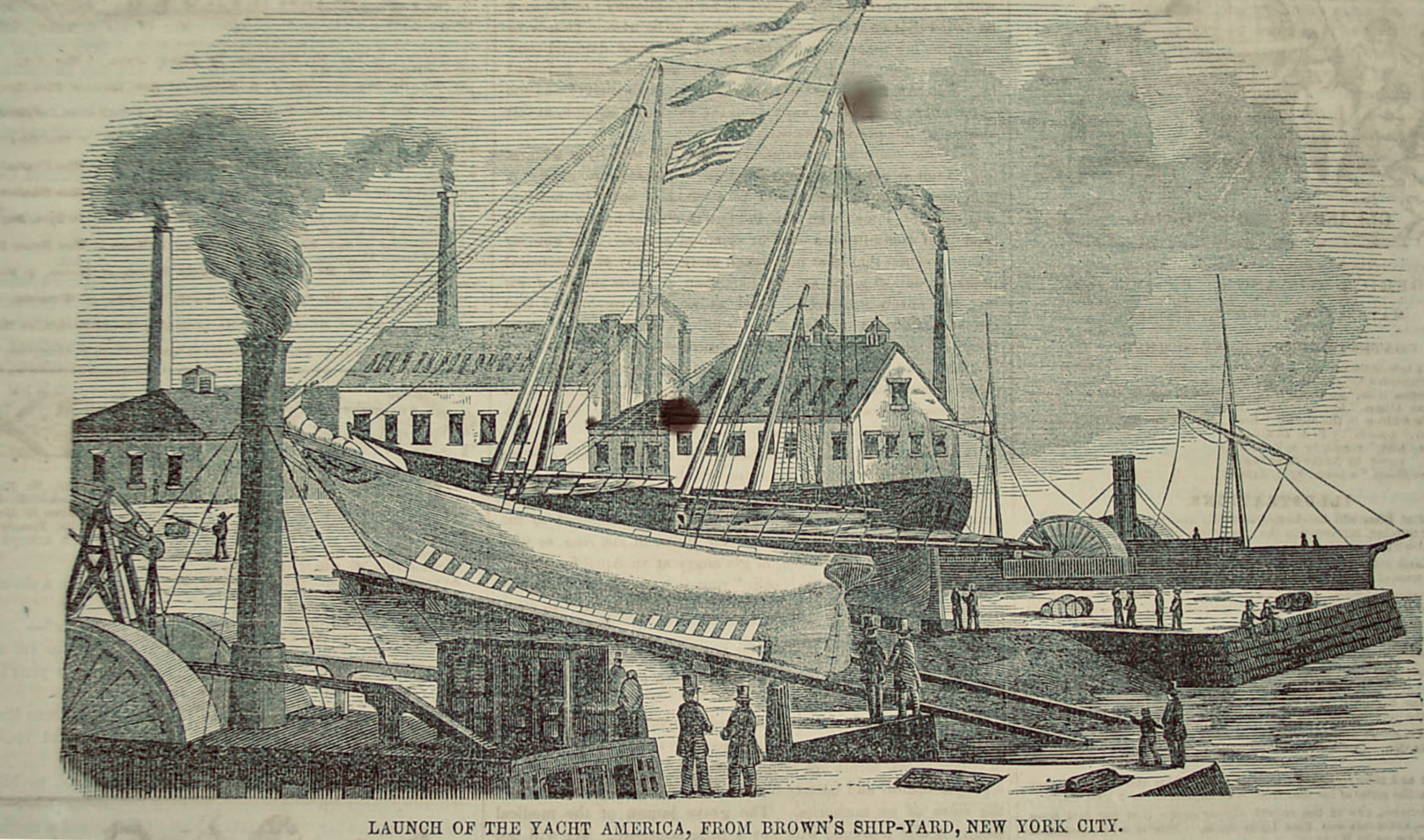

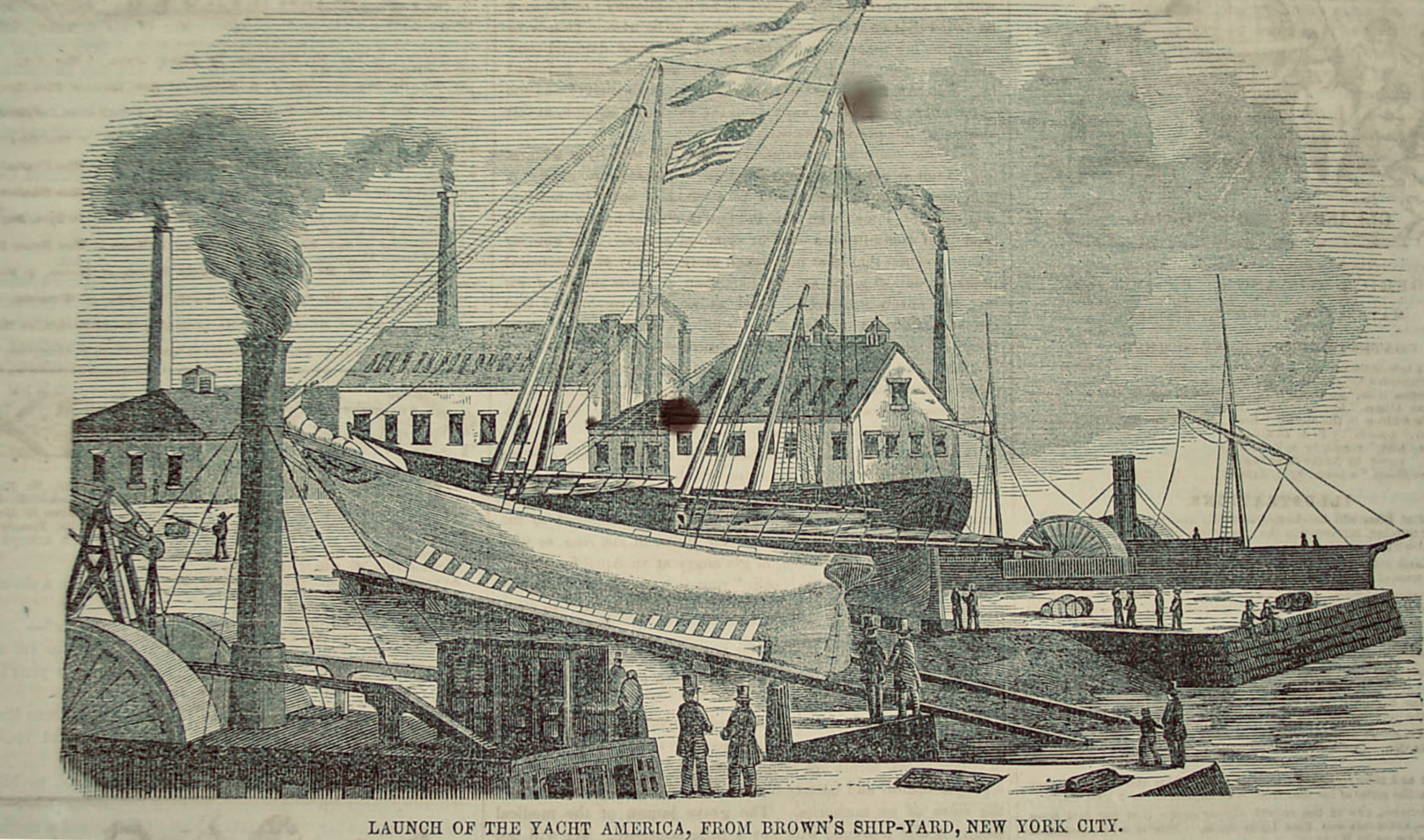

, George Schuyler, Hamilton Wilkes, and J. Beekman Finley, built a yacht to sail to England. The purpose of this visit was twofold: to show off U.S. shipbuilding skill and make money through competing in yachting regattas. Stevens employed the services of the shipyard of William H. Brown and his chief designer, George Steers. She was launched on May 3, 1851, from the Brown shipyard, near Eleventh Street, East River

The East River is a saltwater tidal estuary in New York City. The waterway, which is actually not a river despite its name, connects Upper New York Bay on its south end to Long Island Sound on its north end. It separates the borough of Que ...

, New York. She cost $30,000 () .

Designer

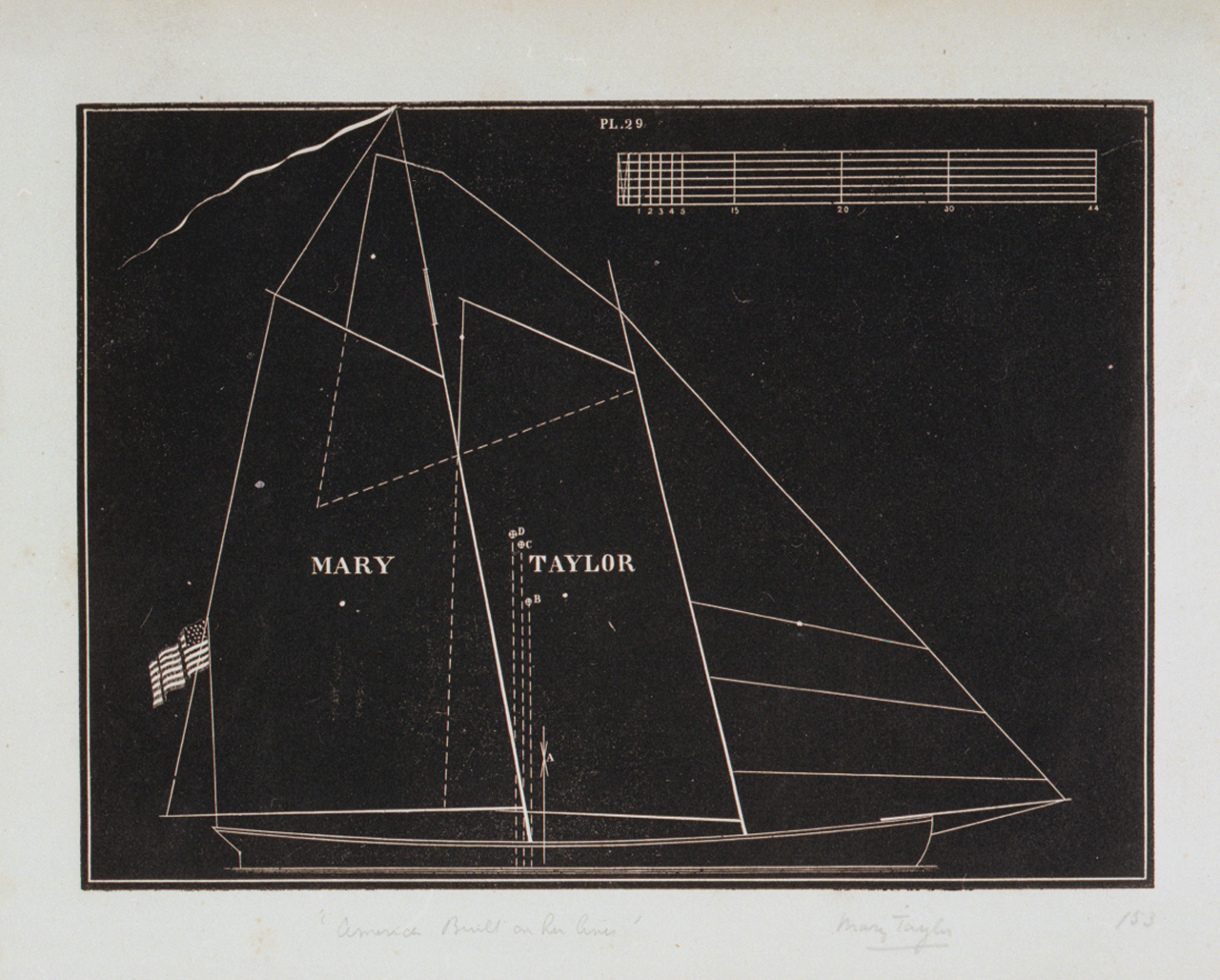

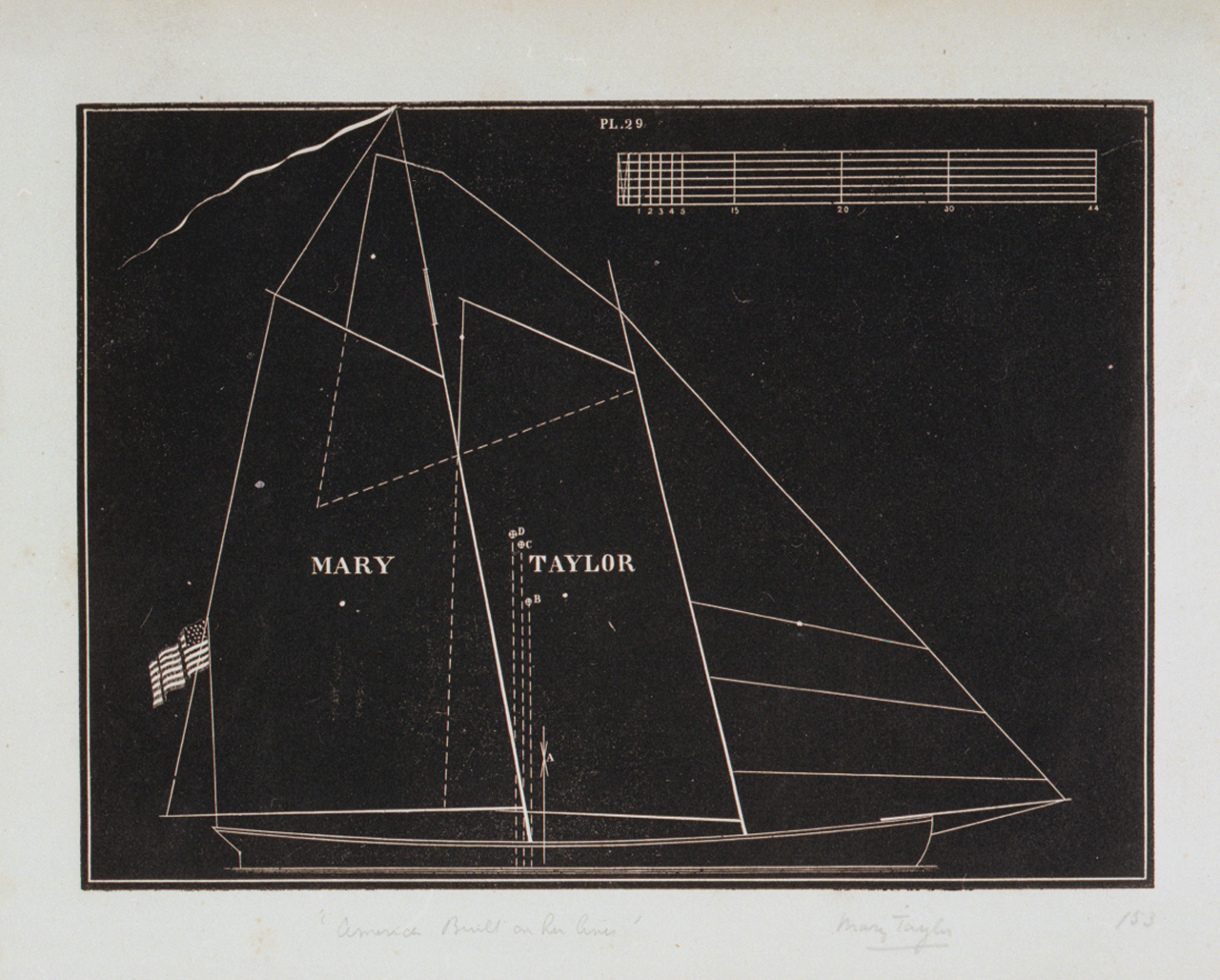

''America'' was designed by James Rich Steers and George Steers (1820–1856) (See George Steers and Co). Traditional "cod-head-and-mackerel-tail" design gave boats a blunt bow and a sharp stern with the widest point (the beam) placed one-third of the length aft of the bow. George Steers' pilot boat designs, however, had a concave clipper-bow with the beam of the vessel at midships. She was designed along the lines of the pilot boat ''Mary Taylor''. As a result, his

''America'' was designed by James Rich Steers and George Steers (1820–1856) (See George Steers and Co). Traditional "cod-head-and-mackerel-tail" design gave boats a blunt bow and a sharp stern with the widest point (the beam) placed one-third of the length aft of the bow. George Steers' pilot boat designs, however, had a concave clipper-bow with the beam of the vessel at midships. She was designed along the lines of the pilot boat ''Mary Taylor''. As a result, his schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoo ...

-rigged pilot boats were among the fastest and most seaworthy of their day. They had to be seaworthy, for they met inbound and outbound vessels in any kind of weather. These vessels also had to be fast, for harbor pilots competed with each other for business. In addition to pilot boats, Steers designed and built 17 yachts, some which were favorites with the New York Yacht Club.

Captain

''America'' was captained by Richard Brown, who was also a skilled member of theSandy Hook

Sandy Hook is a barrier spit in Middletown Township, Monmouth County, New Jersey, United States.

The barrier spit, approximately in length and varying from wide, is located at the north end of the Jersey Shore. It encloses the southern e ...

Pilots group, renowned worldwide for their expertise in manoeuvering the shoals around New York Harbor. They were highly skilled racers as a result of impromptu races between pilots to ships in need of pilot services. Brown had sailed aboard the pilot boat ''Mary Taylor'', designed by George Steers, of whom he was a personal friend. He chose as first mate Nelson Comstock, a newcomer to yacht racing.

Events leading to the race

Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, ver ...

on July 11. They were joined there by Commodore Stevens. After drydocking and repainting ''America'' left for Cowes, Isle of Wight, on July 30. While there the crew enjoyed the hospitality of the Royal Yacht Squadron while Stevens searched for someone who would race against his yacht.

The British yachting community had been following the construction of ''America'' with interest and perhaps some trepidation. When ''America'' showed up on the Solent on July 31 there was one yacht, ''Laverock'', that appeared for an impromptu race. The accounts of the race are contradictory: a British newspaper said ''Laverock'' held her own, but Stevens later reported that ''America'' beat her handily. Whatever the outcome, it seemed to have discouraged other British yachtsmen from challenging ''America'' to a match. She never raced until the last day of the Royal Yacht Squadron's annual members-only regatta for which Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

customarily donated the prize. Because of ''America''s presence, a special provision was made to "open to all nations" a race of 'round the Isle of Wight, with no reservation for time allowance.

The race

The race was held on August 22, 1851, with a 10:00 AM start for a line of seven schooners and another line of eightcutters

Cutter may refer to:

Tools

* Bolt cutter

* Box cutter, aka Stanley knife, a form of utility knife

* Cigar cutter

* Cookie cutter

* Glass cutter

* Meat cutter

* Milling cutter

* Paper cutter

* Side cutter

* Cutter, a type of hydraulic rescue to ...

. ''America'' had a slow start due to a fouled anchor and was well behind when she finally got under way. Within half an hour however, she was in 5th place and gaining.

The eastern shoals of the Isle of Wight are called the Nab Rocks. Traditionally, races would sail around the east (seaward) side of the lightship that marked the edge of the shoal, but one could sail between the lightship and the mainland if they had a knowledgeable pilot. ''America'' had such a pilot and he took her down the west (landward) side of the lightship. After the race a contestant protested this action, but was overruled because the official race rules did not specify on which side of the lightship a boat had to pass.

This tactic put ''America'' in the lead, which she held throughout the rest of the race. At one point the jib boom broke due to a crew error, but it was replaced in fifteen minutes. On the final leg of the race the yacht ''Aurora'' closed but was 18 minutes behind when ''America'' finished shortly after 6:00 PM. Legend has it that while watching the race, Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

asked who was second, and received the famous reply: "There is no second, your Majesty."

Subsequent owners

John Cox Stevens and the syndicate from the New York Yacht Club owned the ''America'' from the time that she was launched on May 3, 1851, until ten days after she won the regatta that made her famous. On September 1, 1851, the yacht was sold to John de Blaquiere, 4th Baron de Blaquiere. In late July 1852, ''America'' ran aground atPortsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city status in the United Kingdom, city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is admi ...

, Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

and was damaged. De Blaquiere raced her only a few times before selling her in 1856 to Henry Montagu Upton, 2nd Viscount Templetown

Viscount Templetown, in the County of Antrim, was a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It was created on 13 February 1806 for John Upton, 2nd Baron Templetown, Member of Parliament for Bury St Edmunds. He was the son of Clotworthy Upton, who ser ...

, who renamed her ''Camilla'' but failed to use or maintain her. In 1858, she was sold to Henry Sotheby Pitcher, a shipbuilder in Northfleet, Kent. He rebuilt ''Camilla'' and sold her to Henry Edward Decie in 1860, who brought her back to the United States. Decie sold the ship to the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confede ...

the same year for use as a blockade runner in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

, though he remained aboard as captain. The yacht was renamed ''Memphis'', but the details of her Confederate service are unclear.

In 1862, she was scuttled in Dunns Creek, north of Crescent City, Florida when Union troops took the city of Jacksonville. She was raised, repaired, and renamed ''America'' by the Union and served the United States Navy on the blockade until May 1863. She was armed with three smoothbore bronze cannon designed by John A. Dahlgren

John Adolphus Bernard Dahlgren (November 13, 1809 – July 12, 1870) was a United States Navy officer who founded his service's Ordnance Department and launched significant advances in gunnery.

Dahlgren devised a smoothbore howitzer, adaptable ...

and cast at the Washington Navy Yard

The Washington Navy Yard (WNY) is the former shipyard and ordnance plant of the United States Navy in Southeast Washington, D.C. It is the oldest shore establishment of the U.S. Navy.

The Yard currently serves as a ceremonial and administra ...

. A 12-pounder was located on the bow and two 24-pounders were placed amidships. She was assigned to the federal blockading squadron off Charleston, South Carolina, and was on patrol the night of March 19, 1863, when she spotted the smoke of a blockade runner near Dewees Inlet, South Carolina. She immediately launched colored signal flares to alert the rest of the fleet. The runner proved to be the CSS ''Georgiana'', which was described as the most powerful Confederate cruiser then afloat. ''America's'' action ultimately resulted in the ''Georgiana''s wreck and destruction. ''Georgiana'' was the most important vessel to be captured or destroyed by the federal blockade. In 1863 ''America'' became a training ship at the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a United States Service academies, federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of ...

. On August 8, 1870, the Navy entered her in the America's Cup race at New York Harbor, where she finished fourth.

''America'' remained in the Navy until 1873, when she was sold to Benjamin Butler for $5,000. Butler hired

''America'' remained in the Navy until 1873, when she was sold to Benjamin Butler for $5,000. Butler hired James H. Reid

James H. Reid, (1842March 7, 1919) was a 19th-century American Maritime pilot. He is best known for being the dean of the Boston pilots, serving for 55 years. He was captain of the famous yacht America (yacht), America for 17 years when she was o ...

who was in charge of her for sixteen years. They raced and maintained her well, commissioning a rebuild by Donald McKay in 1875. Butler and Reid sailed a race with the schooner ''Resolute,'' off the Isles of Shoals and won the race. Later, she sailed a squadron race and won. In the winter 1881, when she was lengthened 6 1/2 feet, Reid and Butler sailed her on a cruise to the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Great ...

returning to Boston in 1882. A total refit of the rig was done in 1885 by Edward Burgess

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sax ...

to keep her competitive. Butler died in 1893 and his son Paul inherited the schooner, but he had no interest in her and gave her to his nephew Butler Ames in 1897. Ames reconditioned ''America'' and used her occasionally for racing and casual sailing until 1901, when she fell into disuse and disrepair.

''America'' was sold to a company headed by Charles Foster in 1917, and in 1921 was sold to the ''America'' Restoration Fund, which donated her to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east ...

.

Fate

In 1923 ''America'' was given the hull designation of IX-41. She was not maintained there either and became seriously decayed by 1940. The shed which housed ''America'' collapsed during a heavy snowstorm on March 29, 1942. The remains of the shed and ship were scrapped and burned in 1945. ''America'' was one of only three ships in commission in the U.S. Navy in both the Civil War and World War II, joined by the USS ''Constitution'' and USS ''Constellation''.Legacy

The New York Yacht Club acquired several relics from ''America'' after her destruction. These include her transom eagle, rudder post and one of her masts. The mast serves as the flag pole for the Club's summer station in Newport, Rhode Island.Replicas

The first replica of ''America'' was built by Goudy & Stevens Shipyard in Boothbay, Maine, and launched in 1967. She was built for Rudolph Schaefer, Jr., owner of F. & M. Schaefer Brewing Co. Construction was supervised by her first skipper, Newfoundland born Capt. Lester G. Hollett. A second replica of ''America'' was built in 1995 by Scarano Boatbuilding of Albany, NY for Ray Giovanni and was operated by him for commercial events until his death. It had several modifications from the original design including widening the beam by 4 feet to accommodate interior layouts. The original design had only one lantern (skylight) so three were added to bring light into the interior of the yacht. The yacht spent several years in Key West Florida and now operates between Key West and New York City seasonally for the company Classic Harbor Line. She was exhibited in June 2011 inSan Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the United States, U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, California, San Jose, and Oakland, Ca ...

in concert with exploratory preparations by the Oracle Racing team for the 2013 America's Cup race, which was held within the bay. She was subsequently owned by Troy Sears's company Next Level Sailing, and sailed around the world as an official licensed partner for the America's Cup Tour.

A third replica was built in Varna, Bulgaria in 2005. Christened ''Skythia'', the boat's home port later was Rostock, Germany, where she was used for commercial charter.

References

External links

* - accurate lines of the ''America'' (1851) * * * {{1862 shipwrecks 1851 in sports 1851 ships America's Cup challengers Individual sailing vessels Schooners of the United States Yachts of New York Yacht Club members Maritime incidents in March 1852 Scuttled vessels Shipwrecks in rivers Maritime incidents in March 1862 Ships built in New York City Former yachts of New York City