Allen Ellender on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

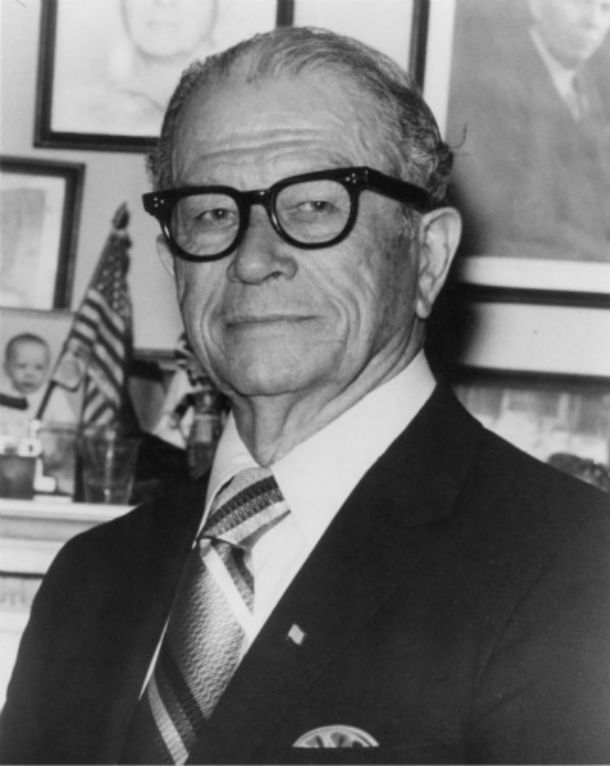

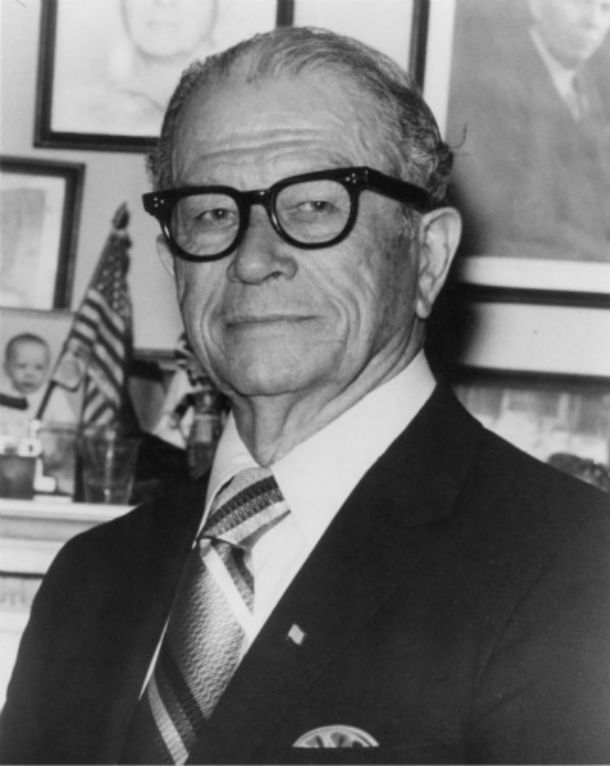

Allen Joseph Ellender (September 24, 1890 – July 27, 1972) was an American politician and lawyer who was a U.S. Senator from

https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1938-pt1-v83/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1938-pt1-v83-16-1.pdf

/ref> Unlike many Democrats he was not a " hawk" in foreign policy and opposed the

In 1972, the Democratic gubernatorial runner-up from December 1971, former state senator J. Bennett Johnston, Jr., of Shreveport, challenged Ellender for renomination. Ellender was expected to defeat Johnston, but he died from a heart attack on July 27, aged 81, at

In 1972, the Democratic gubernatorial runner-up from December 1971, former state senator J. Bennett Johnston, Jr., of Shreveport, challenged Ellender for renomination. Ellender was expected to defeat Johnston, but he died from a heart attack on July 27, aged 81, at

online

* Finley, Keith M. ''Delaying the Dream: Southern Senators and the Fight Against Civil Rights, 1938-1965'' (Baton Rouge, LSU Press, 2008).

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

from 1937 until his death. He was a Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

who was originally allied with Huey Long

Huey Pierce Long Jr. (August 30, 1893September 10, 1935), nicknamed "the Kingfish", was an American politician who served as the 40th governor of Louisiana from 1928 to 1932 and as a United States senator from 1932 until his assassination ...

. As Senator he compiled a generally conservative record, voting 77% of the time with the Conservative Coalition on domestic issues.Becnel, ''Senator Allen Ellender'' p 248 A staunch segregationist

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Interna ...

, he signed the Southern Manifesto in 1956, voted against the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and opposed anti-lynching legislation in 1938.Congressional Record – Senate (January 20, 1938)https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1938-pt1-v83/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1938-pt1-v83-16-1.pdf

/ref> Unlike many Democrats he was not a " hawk" in foreign policy and opposed the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

.

Ellender served as President Pro Tempore, and the chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee. He also served as the chair of the Senate Agriculture Committee for over 16 years.

Early life

Ellender was born in the town of Montegut in Terrebonne Parish, a center ofCajun

The Cajuns (; French: ''les Cadjins'' or ''les Cadiens'' ), also known as Louisiana ''Acadians'' (French: ''les Acadiens''), are a Louisiana French ethnicity mainly found in the U.S. state of Louisiana.

While Cajuns are usually described as ...

culture. He was the son of Victoria Marie (Javeaux) and Wallace Richard Ellender, Sr. He attended public and private schools, and in 1909 he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree from the Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

St. Aloysius College in . (It has been reorganized as Brother Martin High School). He graduated from Tulane University Law School

Tulane University Law School is the law school of Tulane University. It is located on Tulane's Uptown campus in New Orleans, Louisiana. Established in 1847, it is the 12th oldest law school in the United States.

In addition to the usual common ...

in New Orleans with a LL.B.

Bachelor of Laws ( la, Legum Baccalaureus; LL.B.) is an undergraduate law degree in the United Kingdom and most common law jurisdictions. Bachelor of Laws is also the name of the law degree awarded by universities in the People's Republic of Chi ...

in 1913, was admitted to the bar later that year, and launched his practice in Houma.

Early career

Ellender was appointed as the city attorney of Houma, Louisiana, serving from 1913 to 1915, then served as Terrebonne Parish District Attorney from 1915 to 1916.World War I

Though he received a draft deferment forWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Ellender volunteered for military service. Initially rejected on medical grounds after being diagnosed with a kidney stone, Ellender persisted in attempting to serve in uniform. After surgery and recovery, Ellender inquired through his Congressman about obtaining a commission in the Army's Judge Advocate General Corps

The Judge Advocate General's Corps, also known as JAG or JAG Corps, is the military justice branch or specialty of the United States Air Force, Army, Coast Guard, Marine Corps and Navy. Officers serving in the JAG Corps are typically called jud ...

, and was offered a commission as an interpreter and translator in the United States Marine Corps

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through combi ...

, which he declined over concerns that because he spoke Louisiana French

Louisiana French ( frc, français de la Louisiane; lou, françé la lwizyàn) is an umbrella term for the dialects and varieties of the French language spoken traditionally by French Louisianians in colonial Lower Louisiana. As of today Louisi ...

, he might not be proficient enough in the formal French language.

While taking courses to improve his French, he also applied for a position in the Student Army Training Corps at Tulane University. He was accepted into the program in October 1918, and reported to Camp Martin on the Tulane University campus. The war ended in November, and the SATC program was disbanded, so Ellender was released from the service in December before completing his training. Despite attempts lasting into the late 1920s to secure an honorable discharge as proof of his military service, Ellender was unsuccessful in obtaining one. Instead, the commander of Camp Martin replied to an inquiry from Ellender's congressman that "Private Allen J. Ellender" had been released from military service in compliance with an army order prohibiting new enlistments in the SATC after the Armistice of November 11, 1918

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

. As his career progressed, his biography often included the incorrect claim that Ellender had served as a sergeant in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

Artillery Corps during the war.

State politics

Ellender was a delegate to the Louisiana constitutional convention in 1921. The constitution produced by that body was retired in 1974, two years after Ellender's death. He served in the Louisiana House of Representatives from 1924 to 1936. He was floor leader from 1928 to 1932, when in 1929 he worked successfully against the impeachment forces, led by Ralph Norman Bauer and Cecil Morgan, that attempted to removeGovernor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Huey Long for a litany of abuses of power

Abuse is the improper usage or treatment of a thing, often to unfairly or improperly gain benefit. Abuse can come in many forms, such as: physical or verbal maltreatment, injury, assault, violation, rape, unjust practices, crimes, or other t ...

. Ellender was the House Speaker from 1932 to 1936, when he was elected to the US Senate.

U.S. Senator

In 1937 he took his Senate seat, formerly held by the fallen Huey Long and slated for the Democratic nominee Oscar Kelly Allen, Sr., of Winnfield, the seat of Long's home parish of Winn. Allen had won the Democratic nomination by a plurality exceeding 200,000 votes, but he died shortly thereafter. His passing enabled Ellender's election. The Democrats had so dominated state politics since thedisfranchisement

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. D ...

of most blacks at the turn of the century, that the primary was the decisive election for offices.

Ellender was one of twenty liberal Democratic senators in July 1937 who voted against killing the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937

The Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937, frequently called the "court-packing plan",Epstein, at 451. was a legislative initiative proposed by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt to add more justices to the U.S. Supreme Court in order t ...

, which was introduced by President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

in an effort to pack the United States Supreme Court following several anti-New Deal decisions from the Court.

Lorris M. Wimberly of Arcadia in Bienville Parish

Bienville Parish (french: link=no, Paroisse de Bienville, ) is a parish located in the northwestern portion of the U.S. state of Louisiana. At the 2020 census, the population was 12,981. The parish seat is Arcadia.

The highest natural point ...

, meanwhile, succeeded Ellender as House Speaker. Wimberly was the choice of Governor Richard Webster Leche and thereafter Lieutenant Governor Earl Kemp Long

Earl Kemp Long (August 26, 1895 – September 5, 1960) was an American politician and the 45th governor of Louisiana, serving three nonconsecutive terms. Long, known as "Uncle Earl", connected with voters through his folksy demeanor and c ...

, who succeeded Leche to the governorship.

Ellender was repeatedly re-elected to the Senate and served until his death in 1972. He gained seniority and great influence. He was the leading sponsor of the federal free lunch program, which was enacted in 1945 and continues; it was a welfare program that helped poor students.Becnel, ''Senator Allen Ellender'' p 130

In 1946, Ellender defended fellow Southern demagogue Theodore Bilbo

Theodore Gilmore Bilbo (October 13, 1877 – August 21, 1947) was an American politician who twice served as governor of Mississippi (1916–1920, 1928–1932) and later was elected a U.S. Senator (1935–1947). A lifelong Democrat, he was a fil ...

, who incited violence against blacks in his re-election campaign. When a petition was filed to the Senate, a committee chaired by Ellender investigated the voter suppression. Ellender defended the violent attacks on blacks trying to vote as the result of "tradition and custom" rather than Bilbo's incitements. The committee voted on party lines to clear Bilbo, with the three Democrats siding with the Mississippi demagogue while the two conservative Republicans, Bourke Hickenlooper of Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to th ...

and Styles Bridges of New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec to the nor ...

, dissented from the verdict. Bilbo, however, ultimately did not take his Senate seat due to medical issues and died a short time later.

Ellender served as the powerful chairman of the Senate Agriculture Committee

The Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry is a committee of the United States Senate empowered with legislative oversight of all matters relating to the nation's agriculture industry, farming programs, forestry and logging, and legi ...

from 1951 to 1953 and 1955 to 1971, through which capacity he was a strong defender of sugar cane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, perennial grass (in the genus '' Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with stout, jointed, fibrous stalk ...

interests. He chaired the even more powerful Senate Appropriations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Appropriations is a standing committee of the United States Senate. It has jurisdiction over all discretionary spending legislation in the Senate.

The Senate Appropriations Committee is the largest committ ...

from 1971 until his death. Denoting his seniority as a Democrat in the Senate, Ellender was President pro tempore of the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

from 1971 to 1972, an honorific position.

Ellender was an opponent of Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

, who had achieved national prominence through a series of well-publicized speeches and investigations attacking supposed communist infiltration in the US government, army and educational institutions during the 1950s.

In March 1952, Ellender stated the possibility of the House of Representatives electing the president in that year's general election and added that the possibility could arise from the entry of Georgia Senator Richard Russell, Jr. into the general election as a third-party candidate and thereby see neither President Truman or Republican Senator Robert A. Taft

Robert Alphonso Taft Sr. (September 8, 1889 – July 31, 1953) was an American politician, lawyer, and scion of the Republican Party's Taft family. Taft represented Ohio in the United States Senate, briefly served as Senate Majority Leade ...

able to secure enough votes from the Electoral College.

Ellender strongly opposed the federal civil rights legislation of the 1960s, which included the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to enforce blacks' constitutional rights in voting. Many, particularly in the Deep South, had been disfranchised since 1900. In the aftermath of the Duck Hill lynchings, he also helped block a proposed anti-lynching bill which had previously been passed in the House, proclaiming, "We shall at all cost preserve the white supremacy of America." He did support some Louisiana state legislation sought by civil rights groups, such as repeal of the state poll tax (a disfranchisement mechanism).

In late 1962 he underwent a tour of East Africa. In Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a landlocked self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally kno ...

he spoke to the media and was reported by a newspaper to have said he did not believe African territories were ready for self-governance and "incapable of leadership" without the assistance of white people. He was further reported to have said apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

was a proper policy choice and should have been instituted sooner. Ellender later denied making these remarks, but Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa. The country is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. The sou ...

and Tanganyika responded to the allegations by barring him from entering their countries.

On August 31, 1964, during President Johnson's signing of the Food Stamp Act of 1964

The Food Stamp Act (P.L. 88-525) provided permanent legislative authority to the Food Stamp Program, which had been administratively implemented on a pilot basis in 1962. On August 31, 1964 it was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnso ...

, the president noted Ellender as one of the members of Congress he wanted to compliment for playing "a role in the passage of this legislation".

Early in his tenure, the Audubon Society

The National Audubon Society (Audubon; ) is an American non-profit environmental organization dedicated to conservation of birds and their habitats. Located in the United States and incorporated in 1905, Audubon is one of the oldest of such orga ...

, with an interest in the ivory-billed woodpecker

The ivory-billed woodpecker (''Campephilus principalis'') is a possibly extinct woodpecker that is native to the bottomland hardwood forests and temperate coniferous forests of the Southern United States and Cuba. Habitat destruction and hunting ...

, which faced extinction, persuaded Ellender to work for the establishment of the proposed Tensas Swamp National Park to preserve bird habitat: 60,000 acres of land owned by the Singer Sewing Company

Singer Corporation is an American manufacturer of consumer sewing machines, first established as I. M. Singer & Co. in 1851 by Isaac Singer, Isaac M. Singer with New York lawyer Edward Cabot Clark, Edward C. Clark. Best known for its sewing mac ...

in Madison Parish in northeastern Louisiana. Ellender's bill died in committee. In 1998, long after Ellender's death, Congress established the Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge

The Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge is a protected wildlife area located west of the city of Tallulah in Madison, Tensas and Franklin parishes in northeastern Louisiana, USA.

Wildlife and habitat

The refuge is in located in the upper bas ...

.

Sticking with Truman, 1948

Ellender rarely had serious opposition for his Senate seat. In his initial election in 1936, Ellender defeatedU.S. Representative

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they c ...

John N. Sandlin of Louisiana's 4th congressional district

Louisiana's 4th congressional district is a congressional district in the U.S. state of Louisiana. The district is located in the northwestern part of the state and is based in Shreveport- Bossier City. It also includes the cities of Minden, De ...

in the Democratic primary, 364,931 (68 percent) to 167,471 (31.2 percent). Sandlin was from Minden in Webster Parish

Webster Parish (French: ''Paroisse de Webster'') is a parish located in the northwestern section of the U.S. state of Louisiana.

The seat of the parish is Minden.

As of the 2010 census, the Webster Parish population was 41,207. In 2018, the p ...

in northwest Louisiana. There was no Republican opposition to Ellender during much of his tenure.

Ellender was steadfastly loyal to all Democratic presidential nominees and refused to support then Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Strom Thurmond of South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

for president in 1948. That year Thurmond, the States Rights Party nominee, was also listed on the ballot as the official Democratic nominee in Louisiana and three other southern states. Ellender supported Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

, whose name was placed on the ballot only after Governor Earl Kemp Long

Earl Kemp Long (August 26, 1895 – September 5, 1960) was an American politician and the 45th governor of Louisiana, serving three nonconsecutive terms. Long, known as "Uncle Earl", connected with voters through his folksy demeanor and c ...

called a special session

In a legislature, a special session (also extraordinary session) is a period when the body convenes outside of the normal legislative session. This most frequently occurs in order to complete unfinished tasks for the year (often delayed by confli ...

of the legislature to place the president's name on the ballot. "As a Democratic nominee, I am pledged to support the candidate of my party, and that I will do," declared Ellender, though he could have argued that Thurmond, not Truman, was technically the "Democratic nominee" in Louisiana.

Senatorial campaigns of 1954, 1960, and 1966

In 1954, Ellender defeated fellow DemocratFrank Burton Ellis

Frank Burton Ellis (February 10, 1907 – November 3, 1969) was a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana.

Education and career

Born in Covington, Louisiana, Ellis attended the Gul ...

, a former state senator from St. Tammany Parish and later a short term judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana

The United States District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana (in case citations, E.D. La.) is a United States federal court based in New Orleans.

Appeals from the Eastern District of Louisiana are taken to the United States Court of A ...

. Ellender polled 268,054 votes (59.1 percent) in the party primary; Ellis, 162,775 (35.9 percent), with 4 percent for minor candidates. He faced no Republican opposition that year.

In 1960, Ellender was challenged by the former Republican National Committeeman

The Republican National Committee (RNC) is a U.S. political committee that assists the Republican Party of the United States. It is responsible for developing and promoting the Republican brand and political platform, as well as assisting in fu ...

George W. Reese, Jr., a New Orleans lawyer, who in 1952 and 1954 had challenged the conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

Democratic U.S. Representative Felix Edward Hébert

Felix may refer to:

* Felix (name), people and fictional characters with the name

Places

* Arabia Felix is the ancient Latin name of Yemen

* Felix, Spain, a municipality of the province Almería, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, ...

of Louisiana's 1st congressional district

Louisiana's 1st congressional district is a congressional district in the U.S. state of Louisiana. The district comprises land from the northern shore of Lake Pontchartrain south to the Mississippi River delta. It covers most of New Orleans' su ...

, based about New Orleans. In the 1960 campaign, Reese accused Ellender of being "soft on communism". Ellender retorted that Reese's allegation came with "ill grace for the spokesman for the member of a party which has permitted the establishment of a Red-dominated beach head ubaonly ninety miles from our shores to attack my record against the spread of communism."

Reese campaigned across the state in the fall, accompanied at times by Richard Lowrie Hagy of New Orleans, the in-state campaign manager for both Reese and Vice President Richard M. Nixon. In Lake Charles, he claimed that Senator Ellender had been lax in protecting military installations in Louisiana from being downsized or dismantled, with the impacted military services sent to bases in other states. "There has been inadequate representation of the state in these matters," Reese said.

Ellender crushed Reese's hopes of making a respectable showing: he polled 432,228 (79.8 percent); Reese, 109,698 (20.2 percent). Reese's best performance was in two parishes that voted for Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

for president; La Salle Parish

LaSalle Parish (French: ''Paroisse de La Salle'') is a parish located in the U.S. state of Louisiana. As of the 2020 United States Census, the population was 14,791. The parish seat is Jena. The parish was created in 1910 from the western sect ...

(Jena

Jena () is a German city and the second largest city in Thuringia. Together with the nearby cities of Erfurt and Weimar, it forms the central metropolitan area of Thuringia with approximately 500,000 inhabitants, while the city itself has a po ...

) and Ouachita Parish

Ouachita Parish (French: ''Paroisse d'Ouachita'') is located in the northern part of the U.S. state of Louisiana. As of the 2020 census, the population was 160,368. The parish seat is Monroe. The parish was formed in 1807.

Ouachita Parish i ...

( Monroe), but he still gained less than a third of the ballots – 31.3 percent in each. In Caddo Parish ( Shreveport), Reese finished with 30 percent. Reese was only the third Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

since the Seventeenth Amendment was ratified to seek a U.S. Senate seat from Louisiana. Ellender ran 24,889 votes ahead of the John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

- Lyndon Johnson ticket, but 265,965 voters cast in the presidential race ignored the Senate contest, a phenomenon that would later be called an "undervote".

In 1966, Ellender disposed of two weak primary opponents, including the liberal State Senator J. D. DeBlieux (pronounced "W") of Baton Rouge and the conservative businessman Troyce Guice, a native of St. Joseph in Tensas Parish

Tensas Parish (french: Paroisse des Tensas) is a parish located in the northeastern section of the State of Louisiana; its eastern border is the Mississippi River. As of the 2010 census, the population was 5,252. It is the least populated paris ...

, who then resided in Ferriday, and later in Natchez Natchez may refer to:

Places

* Natchez, Alabama, United States

* Natchez, Indiana, United States

* Natchez, Louisiana, United States

* Natchez, Mississippi, a city in southwestern Mississippi, United States

* Grand Village of the Natchez, a site o ...

, Mississippi. The Republicans once again did not field a candidate against Ellender that year.

Ellender cultivated good relationships with the media, whose coverage of his tenure helped him to fend off serious competition. One of his newspaper favorites was Adras LaBorde

Mike Adras (born June 25, 1961) is an American college basketball coach. He most recently was the head men's basketball coach at Northern Arizona University. He was promoted from assistant coach after the 1998–99 season, when Ben Howland left ...

, longtime managing editor of ''Alexandria Daily Town Talk

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

''. The two "Cajuns

The Cajuns (; French: ''les Cadjins'' or ''les Cadiens'' ), also known as Louisiana '' Acadians'' (French: ''les Acadiens''), are a Louisiana French ethnicity mainly found in the U.S. state of Louisiana.

While Cajuns are usually described a ...

" shared fish stories on many occasions.

Last campaign, death, and aftermath

In 1972, the Democratic gubernatorial runner-up from December 1971, former state senator J. Bennett Johnston, Jr., of Shreveport, challenged Ellender for renomination. Ellender was expected to defeat Johnston, but he died from a heart attack on July 27, aged 81, at

In 1972, the Democratic gubernatorial runner-up from December 1971, former state senator J. Bennett Johnston, Jr., of Shreveport, challenged Ellender for renomination. Ellender was expected to defeat Johnston, but he died from a heart attack on July 27, aged 81, at Bethesda Naval Hospital

The Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC), formerly known as the National Naval Medical Center and colloquially referred to as the Bethesda Naval Hospital, Walter Reed, or Navy Med, is a United States' tri-service military medi ...

. Nearly 10 percent of Democratic voters, however, still voted for the deceased Ellender.

Johnston became the Democratic nominee in a manner somewhat reminiscent of how Ellender had won the Senate seat in 1936 after the death of Governor Oscar K. Allen. Johnston easily defeated the Republican candidate, Ben C. Toledano, a prominent attorney from New Orleans who later became a conservative columnist, and former Governor John McKeithen

John Julian McKeithen (May 28, 1918 – June 4, 1999) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 49th governor of Louisiana from 1964 to 1972.

Early life

McKeithen was born in Grayson, Louisiana on May 28, 1918. His father was a ...

, a Democrat running as an Independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independ ...

in the general election because he had not been able to qualify for the primary ballot, given the timing of Ellender's death.

The Ellender family endorsed McKeithen in the 1972 general election because of resentment over Johnston's entry into the race against Ellender."Tim Ellender, McKeithen's State Campaign Manager, Visits Here", ''Tensas Gazette'', St. Joseph, Louisiana, October 26, 1972, p. 1.

Ellender's immediate successor was not Johnston but Elaine S. Edwards, first wife of Governor Edwin Edwards, who was appointed to fill his seat from August 1, 1972, to November 13, 1972. Six days after the election, Johnston was appointed to finish Ellender's remaining term to gain a seniority advantage over other freshman senators.

Legacy

In the Senate, Ellender was known by his colleagues forCajun

The Cajuns (; French: ''les Cadjins'' or ''les Cadiens'' ), also known as Louisiana ''Acadians'' (French: ''les Acadiens''), are a Louisiana French ethnicity mainly found in the U.S. state of Louisiana.

While Cajuns are usually described as ...

cooking, including dishes ranging from roast duck to shrimp jambalaya

Jambalaya ( , ) is an American Creole and Cajun rice dish of French (especially Provençal cuisine), African, and Spanish influence, consisting mainly of meat and vegetables mixed with rice.

Ingredients

Traditionally, the meat includes sa ...

. As of 2009, the Senate dining room still served "Ellender Gumbo

Gumbo (Louisiana Creole: Gombo) is a soup popular in the U.S. state of Louisiana, and is the official state cuisine. Gumbo consists primarily of a strongly-flavored stock, meat or shellfish (or sometimes both), a thickener, and the Creole "h ...

."

Ellender Memorial High School in Houma and Allen Ellender School in Marrero are named in his honor.

In 1994, Ellender was inducted posthumously into the Louisiana Political Museum and Hall of Fame The Louisiana Political Museum and Hall of Fame is a museum and hall of fame located in Winnfield, Louisiana. Created by a 1987 act of the Louisiana State Legislature, it honors the best-known politicians and political journalists in the state.

H ...

in Winnfield.

The Allen J. Ellender Memorial Library on the campus of Nicholls State University in Thibodaux

Thibodaux ( ) is a city in, and the parish seat of, Lafourche Parish, Louisiana, United States, along the banks of Bayou Lafourche in the northwestern part of the parish. The population was 15,948 at the 2020 census. Thibodaux is a principal city ...

is named after him.

See also

* List of United States Congress members who died in office (1950–99)References

Further reading

* Becnel, Thomas. ''Senator Allen Ellender of Louisiana: a biography'' (1996), the standard scholarly biographonline

* Finley, Keith M. ''Delaying the Dream: Southern Senators and the Fight Against Civil Rights, 1938-1965'' (Baton Rouge, LSU Press, 2008).

External links

* https://web.archive.org/web/20090703054258/http://cityofwinnfield.com/museum.html * https://web.archive.org/web/20070127233419/http://www.legis.state.la.us/members/h1812-2008.pdfExternal links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Ellender, Allen J. 1890 births 1972 deaths 20th-century American lawyers 20th-century American politicians American segregationists American white supremacists Brother Martin High School alumni Cajun people Democratic Party United States senators from Louisiana Huey Long Lawyers from New Orleans People from Houma, Louisiana Politicians from New Orleans Presidents pro tempore of the United States Senate Speakers of the Louisiana House of Representatives Democratic Party members of the Louisiana House of Representatives Tulane University Law School alumni Tulane University alumni