Alizon Device on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The trials of the Pendle witches in 1612 are among the most famous

The trials of the Pendle witches in 1612 are among the most famous

The accused witches lived in the area around

The accused witches lived in the area around

One of the accused, Demdike, had been regarded in the area as a witch for fifty years, and some of the deaths the witches were accused of had happened many years before Roger Nowell started to take an interest in 1612. The event that seems to have triggered Nowell's investigation, culminating in the Pendle witch trials, occurred on 21 March 1612.

On her way to

One of the accused, Demdike, had been regarded in the area as a witch for fifty years, and some of the deaths the witches were accused of had happened many years before Roger Nowell started to take an interest in 1612. The event that seems to have triggered Nowell's investigation, culminating in the Pendle witch trials, occurred on 21 March 1612.

On her way to

All the other accused lived in Lancashire, so they were sent to Lancaster Assizes for trial, where the judges were once again Altham and Bromley. The prosecutor was local magistrate Roger Nowell, who had been responsible for collecting the various statements and confessions from the accused. Nine-year-old Jennet Device was a key witness for the prosecution, something that would not have been permitted in many other 17th-century criminal trials. However, King James had made a case for suspending the normal rules of evidence for witchcraft trials in his ''Daemonologie''. As well as identifying those who had attended the Malkin Tower meeting, Jennet also gave evidence against her mother, brother, and sister.

Nine of the accused – Alizon Device, Elizabeth Device, James Device, Anne Whittle, Anne Redferne, Alice Nutter, Katherine Hewitt, John Bulcock and Jane Bulcock – were found guilty during the two-day trial and hanged at Gallows Hill in Lancaster on 20 August 1612; Elizabeth Southerns died while awaiting trial. Only one of the accused, Alice Grey, was found not guilty.

18 August

Anne Whittle (Chattox) was accused of the murder of Robert Nutter. She pleaded not guilty, but the confession she had made to Roger Nowell—likely under torture—was read out in court, and evidence against her was presented by James Robinson, who had lived with the Chattox family 20 years earlier. He claimed to remember that Nutter had accused Chattox of turning his beer sour, and that she was commonly believed to be a witch. Chattox broke down and admitted her guilt, calling on God for forgiveness and the judges to be merciful to her daughter, Anne Redferne.

Elizabeth Device was charged with the murders of James Robinson, John Robinson and, together with Alice Nutter and Demdike, the murder of Henry Mitton. Elizabeth Device vehemently maintained her innocence. Potts records that "this odious witch" suffered from a facial deformity resulting in her left eye being set lower than her right. The main witness against Device was her daughter, Jennet, who was about nine years old. When Jennet was brought into the courtroom and asked to stand up and give evidence against her mother, Elizabeth, confronted with her own child making accusations that would lead to her execution, began to curse and scream at her daughter, forcing the judges to have her removed from the courtroom before the evidence could be heard. Jennet was placed on a table and stated that she believed her mother had been a witch for three or four years. She also said her mother had a

All the other accused lived in Lancashire, so they were sent to Lancaster Assizes for trial, where the judges were once again Altham and Bromley. The prosecutor was local magistrate Roger Nowell, who had been responsible for collecting the various statements and confessions from the accused. Nine-year-old Jennet Device was a key witness for the prosecution, something that would not have been permitted in many other 17th-century criminal trials. However, King James had made a case for suspending the normal rules of evidence for witchcraft trials in his ''Daemonologie''. As well as identifying those who had attended the Malkin Tower meeting, Jennet also gave evidence against her mother, brother, and sister.

Nine of the accused – Alizon Device, Elizabeth Device, James Device, Anne Whittle, Anne Redferne, Alice Nutter, Katherine Hewitt, John Bulcock and Jane Bulcock – were found guilty during the two-day trial and hanged at Gallows Hill in Lancaster on 20 August 1612; Elizabeth Southerns died while awaiting trial. Only one of the accused, Alice Grey, was found not guilty.

18 August

Anne Whittle (Chattox) was accused of the murder of Robert Nutter. She pleaded not guilty, but the confession she had made to Roger Nowell—likely under torture—was read out in court, and evidence against her was presented by James Robinson, who had lived with the Chattox family 20 years earlier. He claimed to remember that Nutter had accused Chattox of turning his beer sour, and that she was commonly believed to be a witch. Chattox broke down and admitted her guilt, calling on God for forgiveness and the judges to be merciful to her daughter, Anne Redferne.

Elizabeth Device was charged with the murders of James Robinson, John Robinson and, together with Alice Nutter and Demdike, the murder of Henry Mitton. Elizabeth Device vehemently maintained her innocence. Potts records that "this odious witch" suffered from a facial deformity resulting in her left eye being set lower than her right. The main witness against Device was her daughter, Jennet, who was about nine years old. When Jennet was brought into the courtroom and asked to stand up and give evidence against her mother, Elizabeth, confronted with her own child making accusations that would lead to her execution, began to curse and scream at her daughter, forcing the judges to have her removed from the courtroom before the evidence could be heard. Jennet was placed on a table and stated that she believed her mother had been a witch for three or four years. She also said her mother had a

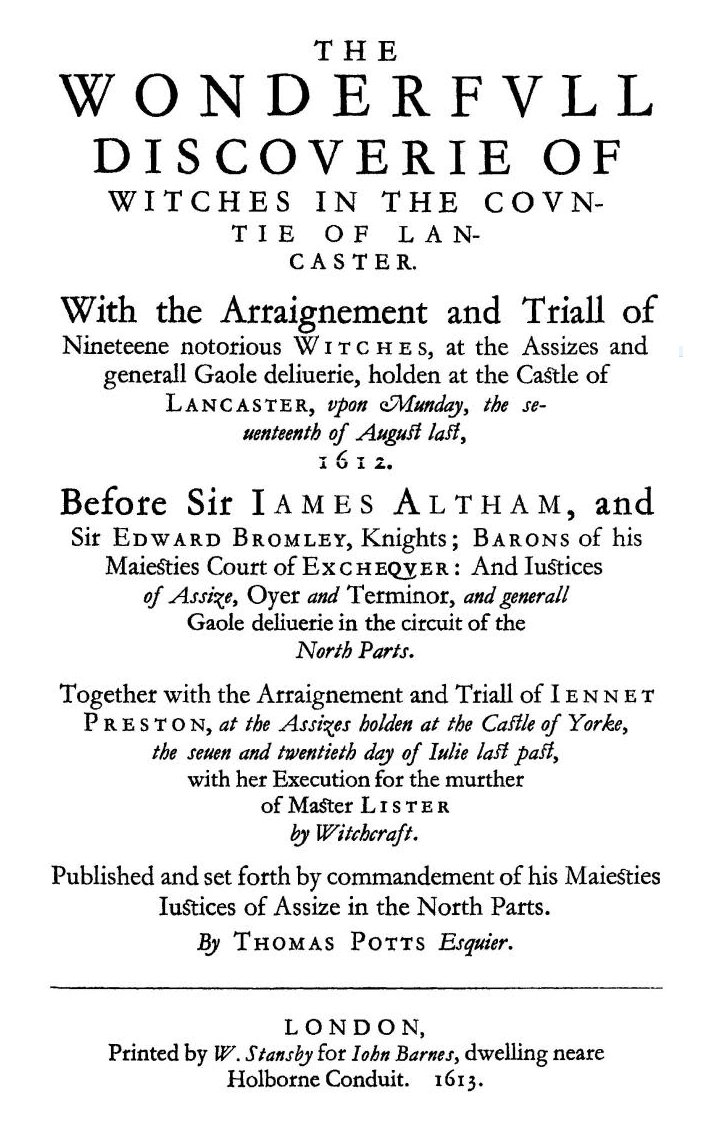

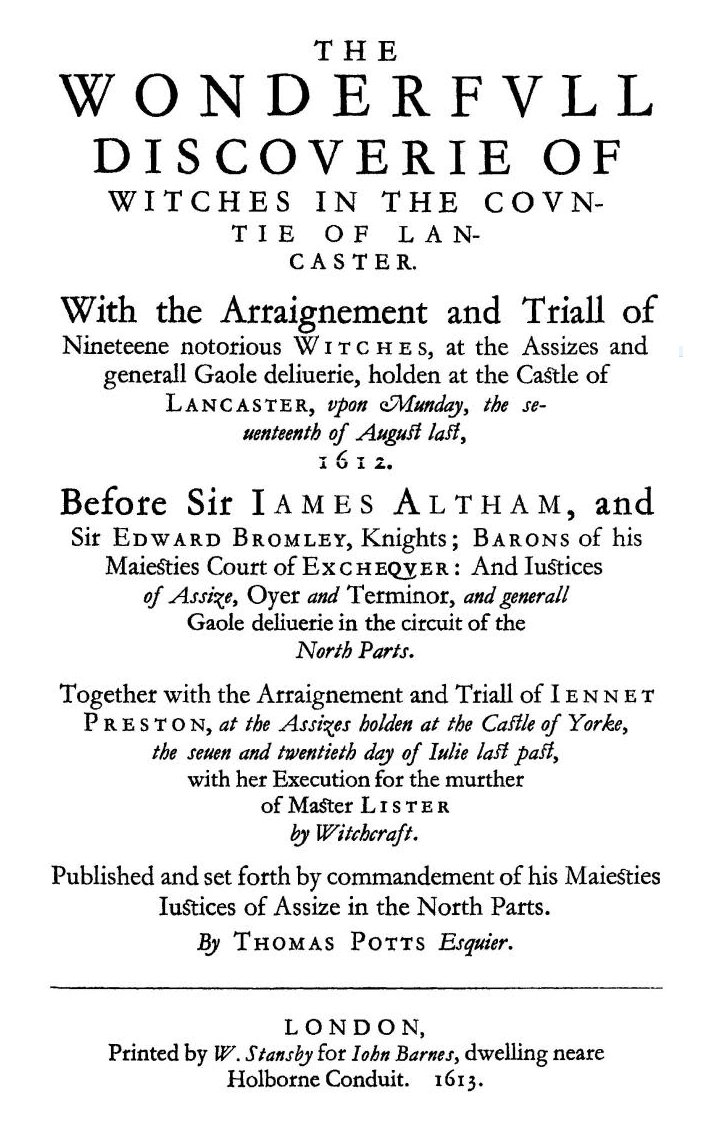

Almost everything that is known about the trials comes from a report of the proceedings written by Thomas Potts, the clerk to the Lancaster Assizes. Potts was instructed to write his account by the trial judges, and had completed the work by 16 November 1612, when he submitted it for review. Bromley revised and corrected the manuscript before its publication in 1613, declaring it to be "truly reported" and "fit and worthie to be published".

Although written as an apparently verbatim account, ''The Wonderfull Discoverie'' is not a report of what was actually said at the trial but is instead reflecting what happened. Nevertheless, Potts "seems to give a generally trustworthy, although not comprehensive, account of an Assize witchcraft trial, provided that the reader is constantly aware of his use of written material instead of verbatim reports".

The trials took place not quite seven years after the

Almost everything that is known about the trials comes from a report of the proceedings written by Thomas Potts, the clerk to the Lancaster Assizes. Potts was instructed to write his account by the trial judges, and had completed the work by 16 November 1612, when he submitted it for review. Bromley revised and corrected the manuscript before its publication in 1613, declaring it to be "truly reported" and "fit and worthie to be published".

Although written as an apparently verbatim account, ''The Wonderfull Discoverie'' is not a report of what was actually said at the trial but is instead reflecting what happened. Nevertheless, Potts "seems to give a generally trustworthy, although not comprehensive, account of an Assize witchcraft trial, provided that the reader is constantly aware of his use of written material instead of verbatim reports".

The trials took place not quite seven years after the

Altham continued with his judicial career until his death in 1617, and Bromley achieved his desired promotion to the Midlands Circuit in 1616. Potts was given the keepership of Skalme Park by James in 1615, to breed and train the king's hounds. In 1618, he was given responsibility for "collecting the forfeitures on the laws concerning sewers, for twenty-one years". Having played her part in the deaths of her mother, brother, and sister, Jennet Device may eventually have found herself accused of witchcraft. A woman with that name was listed in a group of 20 tried at Lancaster Assizes on 24 March 1634, although it cannot be certain that it was the same Jennet Device. The charge against her was the murder of Isabel Nutter, William Nutter's wife. In that series of trials the chief prosecution witness was a ten-year-old boy,

Altham continued with his judicial career until his death in 1617, and Bromley achieved his desired promotion to the Midlands Circuit in 1616. Potts was given the keepership of Skalme Park by James in 1615, to breed and train the king's hounds. In 1618, he was given responsibility for "collecting the forfeitures on the laws concerning sewers, for twenty-one years". Having played her part in the deaths of her mother, brother, and sister, Jennet Device may eventually have found herself accused of witchcraft. A woman with that name was listed in a group of 20 tried at Lancaster Assizes on 24 March 1634, although it cannot be certain that it was the same Jennet Device. The charge against her was the murder of Isabel Nutter, William Nutter's wife. In that series of trials the chief prosecution witness was a ten-year-old boy,

The trials of the Pendle witches in 1612 are among the most famous

The trials of the Pendle witches in 1612 are among the most famous witch trials

A witch-hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. The classical period of witch-hunts in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America took place in the Early Modern per ...

in English history, and some of the best recorded of the 17th century. The twelve accused lived in the area surrounding Pendle Hill

Pendle Hill is in the east of Lancashire, England, near the towns of Burnley, Nelson, Colne, Brierfield, Clitheroe and Padiham. Its summit is above mean sea level. It gives its name to the Borough of Pendle. It is an isolated hill in the Pe ...

in Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashi ...

, and were charged with the murders of ten people by the use of witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have us ...

. All but two were tried at Lancaster Assizes

The courts of assize, or assizes (), were periodic courts held around England and Wales until 1972, when together with the quarter sessions they were abolished by the Courts Act 1971 and replaced by a single permanent Crown Court. The assizes e ...

on 18–19 August 1612, along with the Samlesbury witches

The Samlesbury witches were three women from the Lancashire village of Samlesbury – Jane Southworth, Jennet Bierley, and Ellen Bierley – accused by a 14-year-old girl, Grace Sowerbutts, of practising witchcraft. Their trial at Lan ...

and others, in a series of trials that have become known as the Lancashire witch trials. One was tried at York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

Assizes on 27 July 1612, and another died in prison. Of the eleven who went to trial – nine women and two men – ten were found guilty and executed by hanging; one was found not guilty.

The official publication of the proceedings by the clerk to the court, Thomas Potts

Thomas Henry Potts (23 December 1824 – 27 July 1888) was a British-born New Zealand naturalist, ornithologist, entomologist, and botanist. He also served in the New Zealand Parliament from 1866 to 1870.

Biography

The son of a small ar ...

, in his ''The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster

''The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster'' is the account of a series of English witch trials that took place on 18–19 August 1612, commonly known as the Lancashire witch trials. Except for one trial held in York ...

'', and the number of witches hanged together – nine at Lancaster and one at York – make the trials unusual for England at that time. It has been estimated that all the English witch trials between the early 15th and early 18th centuries resulted in fewer than 500 executions; this series of trials accounts for more than two per cent of that total.

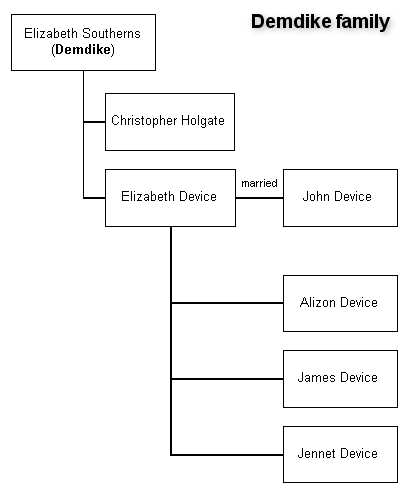

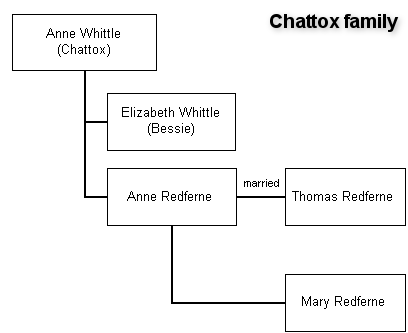

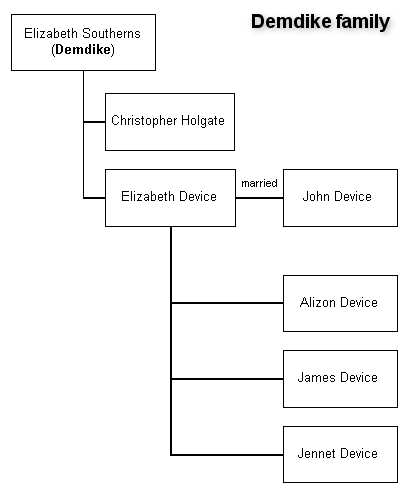

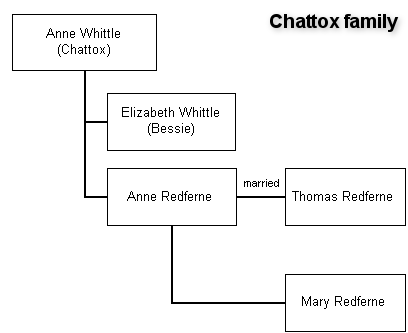

Six of the Pendle witches came from one of two families, each at the time headed by a woman in her eighties: Elizabeth Southerns (a.k.a. Demdike), her daughter Elizabeth Device, and her grandchildren James and Alizon Device; Anne Whittle (a.k.a. Chattox), and her daughter Anne Redferne. The others accused were Jane Bulcock and her son John Bulcock, Alice Nutter, Katherine Hewitt, Alice Grey, and Jennet Preston. The outbreaks of 'witchcraft' in and around Pendle may suggest that some people made a living as traditional healers, using a mixture of herbal medicine

Herbal medicine (also herbalism) is the study of pharmacognosy and the use of medicinal plants, which are a basis of traditional medicine. With worldwide research into pharmacology, some herbal medicines have been translated into modern remed ...

and talisman

A talisman is any object ascribed with religious or magical powers intended to protect, heal, or harm individuals for whom they are made. Talismans are often portable objects carried on someone in a variety of ways, but can also be installed perm ...

s or charms

Charm may refer to:

Social science

* Charisma, a person or thing's pronounced ability to attract others

* Superficial charm, flattery, telling people what they want to hear

Science and technology

* Charm quark, a type of elementary particle

* Cha ...

, which might leave them open to charges of sorcery

Sorcery may refer to:

* Magic (supernatural), the application of beliefs, rituals or actions employed to subdue or manipulate natural or supernatural beings and forces

** Witchcraft, the practice of magical skills and abilities

* Magic in fiction, ...

. Many of the allegations resulted from accusations that members of the Demdike and Chattox families made against each other, perhaps because they were in competition, both trying to make a living from healing, begging, and extortion.

Religious and political background

The accused witches lived in the area around

The accused witches lived in the area around Pendle Hill

Pendle Hill is in the east of Lancashire, England, near the towns of Burnley, Nelson, Colne, Brierfield, Clitheroe and Padiham. Its summit is above mean sea level. It gives its name to the Borough of Pendle. It is an isolated hill in the Pe ...

in Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashi ...

, a county which, at the end of the 16th century, was regarded by the authorities as a wild and lawless region: an area "fabled for its theft, violence and sexual laxity, where the church was honoured without much understanding of its doctrines by the common people". The nearby Cistercian

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint ...

abbey at Whalley had been dissolved by Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

in 1537, a move strongly resisted by the local people, over whose lives the abbey had until then exerted a powerful influence. Despite the abbey's closure, and the execution of its abbot, the people of Pendle remained largely faithful to their Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

beliefs and were quick to revert to Catholicism on Queen Mary's accession to the throne in 1553.

When Mary's Protestant half-sister Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

came to the throne in 1558 Catholic priests once again had to go into hiding, but in remote areas such as Pendle they continued to celebrate Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

in secret. In 1562, early in her reign, Elizabeth passed a law in the form of '' An Act Against Conjurations, Enchantments and Witchcrafts'' (5 Eliz. I c. 16). This demanded the death penalty, but only where harm had been caused; lesser offences were punishable by a term of imprisonment. The Act provided that anyone who should "use, practise, or exercise any Witchcraft, Enchantment, Charm, or Sorcery, whereby any person shall happen to be killed or destroyed", was guilty of a felony without benefit of clergy

In English law, the benefit of clergy (Law Latin: ''privilegium clericale'') was originally a provision by which clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, ...

, and was to be put to death.

On Elizabeth's death in 1603 she was succeeded by James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

. Strongly influenced by Scotland's separation from the Catholic Church during the Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process by which Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland broke with the Pope, Papacy and developed a predominantly Calvinist national Church of Scotland, Kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterianism, Presbyterian in ...

, James was intensely interested in Protestant theology, focusing much of his curiosity on the theology of witchcraft. By the early 1590s he had become convinced that he was being plotted against by Scottish witches. After a visit to Denmark, he had attended the trial in 1590 of the North Berwick witches

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north'' is ...

, who were convicted of using witchcraft to send a storm against the ship that carried James and his wife Anne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female given name Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie.

Anne is sometimes used as a male name in the ...

back to Scotland. In 1597 he wrote a book, ''Daemonologie

''Daemonologie''—in full ''Daemonologie, In Forme of a Dialogue, Divided into three Books: By the High and Mighty Prince, James &c.''—was first published in 1597 by King James VI of Scotland (later also James I of England) as a philosophi ...

'', instructing his followers that they must denounce and prosecute any supporters or practitioners of witchcraft. One year after James acceded to the English throne, a law was enacted imposing the death penalty in cases where it was proven that harm had been caused through the use of magic, or corpses had been exhumed for magical purposes. James was, however, sceptical of the evidence presented in witch trials, even to the extent of personally exposing discrepancies in the testimonies presented against some accused witches.

In early 1612, the year of the trials, every justice of the peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

(JP) in Lancashire was ordered to compile a list of recusant

Recusancy (from la, recusare, translation=to refuse) was the state of those who remained loyal to the Catholic Church and refused to attend Church of England services after the English Reformation.

The 1558 Recusancy Acts passed in the reign ...

s in their area, i.e. those who refused to attend the English Church and to take communion, a criminal offence at that time. Roger Nowell of Read Hall, on the edge of Pendle Forest, was the JP for Pendle. It was against this background of seeking out religious nonconformists that, in March 1612, Nowell investigated a complaint made to him by the family of John Law, a pedlar, who claimed to have been injured by witchcraft. Many of those who subsequently became implicated as the investigation progressed did indeed consider themselves to be witches, in the sense of being village healers who practised magic, probably in return for payment, but such men and women were common in 16th-century rural England, an accepted part of village life.

It was perhaps difficult for the judges charged with hearing the trials – Sir James Altham

Sir James Altham (died 1617) was an English judge and briefly a member of the Parliament of England. A friend of Lord Chancellor Francis Bacon, Altham opposed Edward Coke but advanced the laws of equity behind the fastness of the Exchequer court ...

and Sir Edward Bromley – to understand King James's attitude towards witchcraft. The king was head of the judiciary, and Bromley was hoping for promotion to a circuit nearer London. Altham was nearing the end of his judicial career, but he had recently been accused of a miscarriage of justice at the York Assizes, which had resulted in a woman being sentenced to death by hanging for witchcraft. The judges may have been uncertain whether the best way to gain the King's favour was by encouraging convictions, or by "sceptically testing the witnesses to destruction".

Events leading up to the trials

One of the accused, Demdike, had been regarded in the area as a witch for fifty years, and some of the deaths the witches were accused of had happened many years before Roger Nowell started to take an interest in 1612. The event that seems to have triggered Nowell's investigation, culminating in the Pendle witch trials, occurred on 21 March 1612.

On her way to

One of the accused, Demdike, had been regarded in the area as a witch for fifty years, and some of the deaths the witches were accused of had happened many years before Roger Nowell started to take an interest in 1612. The event that seems to have triggered Nowell's investigation, culminating in the Pendle witch trials, occurred on 21 March 1612.

On her way to Trawden Forest

Trawden Forest is a civil parish in the Pendle district of Lancashire, England. It has a population of 2,765, and contains the village of Trawden (formerly called Beardshaw) and the hamlets of Cottontree, Winewall and Wycoller. Boulsworth Hi ...

, Demdike's granddaughter, Alizon Device, encountered John Law, a pedlar from Halifax, and asked him for some pins. Seventeenth-century metal pins were handmade and relatively expensive, but they were frequently needed for magical purposes, such as in healing – particularly for treating warts – divination, and for love magic

Love magic is the belief that magic can conjure sexual passion or romantic love. Love magic is often used in literature, like fantasy or mythology, and it is believed it can be implemented in a variety of ways, such as by written spells, dolls, ...

, which may have been why Alizon was so keen to get hold of them and why Law was so reluctant to sell them to her. Whether she meant to buy them, as she claimed, and Law refused to undo his pack for such a small transaction, or whether she had no money and was begging for them, as Law's son Abraham claimed, is unclear. According to the 1613 tract "Potts Discovery Of Witches", the Devil appeared in the likeness of a black or brown dog with fiery eyes; which Jennet Device later claimed was a spirit familiar of her grandmother named Ball; which spoke twice in English offering to lame him. A few minutes after the encounter with Alizon Device, she said saw Law stumble and fall, apparently lame, perhaps because he suffered a stroke; he managed to regain his feet and reach a nearby inn. Initially Law made no accusations against Alizon, but she appears to have been convinced of her own powers; when Abraham Law took her to visit his father a few days after the incident, she reportedly confessed, and asked for his forgiveness.

Alizon Device, her mother Elizabeth, and her brother James were summoned to appear before Nowell on 30 March 1612. Alizon confessed that she had sold her soul to the Devil, and that she had told him to lame John Law after he had called her a thief. Her brother, James, stated that his sister had also confessed to bewitching a local child. Elizabeth was more reticent, admitting only that her mother, Demdike, had a mark on her body, something that many, including Nowell, would have regarded as having been left by the Devil after he had sucked her blood. When questioned about Anne Whittle (Chattox), the matriarch of the other family reputedly involved in witchcraft in and around Pendle, Alizon perhaps saw an opportunity for revenge. There may have been bad blood between the two families, possibly dating from 1601, when a member of Chattox's family broke into Malkin Tower

Malkin Tower (or the Malking Tower or Mocking Tower) was the home of Elizabeth Southerns, also known as Demdike, and her granddaughter Alizon Device, two of the chief protagonists in the Lancashire witch trials of 1612.

Perhaps the best-known a ...

, the home of the Devices, and stole goods worth about £1, equivalent to about £117 as of 2018. Alizon accused Chattox of murdering four men by witchcraft, and of killing her father, John Device, who had died in 1601. She claimed that her father had been so frightened of Old Chattox that he had agreed to give her of oatmeal each year in return for her promise not to hurt his family. The meal was handed over annually until the year before John's death; on his deathbed John claimed that his sickness had been caused by Chattox because they had not paid for protection.

On 2 April 1612, Demdike, Chattox, and Chattox's daughter Anne Redferne, were summoned to appear before Nowell. Both Demdike and Chattox were by then blind and in their eighties, and both provided Nowell with damaging confessions. Demdike claimed that she had given her soul to the Devil 20 years previously, and Chattox that she had given her soul to "a Thing like a Christian man", on his promise that "she would not lack anything and would get any revenge she desired". Although Anne Redferne made no confession, Demdike said that she had seen her making clay figures. Margaret Crooke, another witness seen by Nowell that day, claimed that her brother had fallen sick and died after having had a disagreement with Redferne, and that he had frequently blamed her for his illness. Based on the evidence and confessions he had obtained, Nowell committed Demdike, Chattox, Anne Redferne and Alizon Device to Lancaster Gaol, to be tried for ''maleficium

Maleficium may refer to:

* ''Maleficium'' (sorcery), a Latin term meaning "evildoing", "wrongdoing", or "mischief", and describing malevolent, dangerous, or harmful magic

* ''Maleficium'' (album), a 1996 album by Morgana Lefay

* ''Maleficium'', ...

'' – causing harm by witchcraft – at the next assizes.

Meeting at Malkin Tower

The committal and subsequent trial of the four women might have been the end of the matter, had it not been for a meeting organised by Elizabeth Device at Malkin Tower, the home of the Demdikes, held onGood Friday

Good Friday is a Christian holiday commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus and his death at Calvary. It is observed during Holy Week as part of the Paschal Triduum. It is also known as Holy Friday, Great Friday, Great and Holy Friday (also Hol ...

10 April 1612. To feed the party, James Device stole a neighbour's sheep.

Friends and others sympathetic to the family attended, and when word of it reached Roger Nowell, he decided to investigate. On 27 April 1612, an inquiry was held before Nowell and another magistrate, Nicholas Bannister, to determine the purpose of the meeting at Malkin Tower, who had attended, and what had happened there. As a result of the inquiry, eight more people were accused of witchcraft and committed for trial: Elizabeth Device, James Device, Alice Nutter, Katherine Hewitt, John Bulcock, Jane Bulcock, Alice Grey and Jennet Preston. Preston lived across the border in Yorkshire, so she was sent for trial at York Assizes; the others were sent to Lancaster Gaol, to join the four already imprisoned there.

Malkin Tower is believed to have been near the village of Newchurch in Pendle

Newchurch in Pendle is a village in the civil parish of Goldshaw Booth, Pendle, Lancashire, England, adjacent to Barley, to the south of Pendle Hill. It was formerly part of Roughlee Booth until its transferral in 1935.

History

Famous for the ...

, or possibly in Blacko

Blacko is a village and civil parish in the Pendle district of Lancashire, England. Before local government reorganisation in 1974 the village lay on the border with the West Riding of Yorkshire. The parish has a population of 672. The villag ...

on the site of present-day Malkin Tower Farm, and to have been demolished soon after the trials.

Trials

The Pendle witches were tried in a group that also included theSamlesbury witches

The Samlesbury witches were three women from the Lancashire village of Samlesbury – Jane Southworth, Jennet Bierley, and Ellen Bierley – accused by a 14-year-old girl, Grace Sowerbutts, of practising witchcraft. Their trial at Lan ...

, Jane Southworth, Jennet Brierley, and Ellen Brierley, the charges against whom included child murder

Pedicide, child murder, child manslaughter, or child homicide is the homicide of an individual who is a minor.

Punishment by jurisdiction

United States

In 2008, there were 1,494 child homicides in the United States. Of those killed, 1,03 ...

, cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is well documented, b ...

; Margaret Pearson, the so-called Padiham witch

Margaret Pearson, also known as the Padiham witch because she lived in the town of Padiham in Lancashire, England, was among those tried with the Pendle witches in the Lancashire witch trials of 1612. This, her third trial for witchcraft, took pla ...

, who was facing her third trial for witchcraft, this time for killing a horse; and Isobel Robey from Windle, accused of using witchcraft to cause sickness.

Some of the accused Pendle witches, such as Alizon Device, seem to have genuinely believed in their guilt, but others protested their innocence to the end. Jennet Preston was the first to be tried, at York Assizes.

York Assizes, 27 July 1612

Jennet Preston lived inGisburn

Gisburn (formerly Gisburne) is a village and civil parish within the Ribble Valley borough of Lancashire, England. Historically within the West Riding of Yorkshire, it lies northeast of Clitheroe and west of Skipton. The civil parish had a pop ...

, which was then in Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

, so she was sent to York Assizes for trial. Her judges were Sir James Altham and Sir Edward Bromley. Jennet was charged with the murder by witchcraft of a local landowner, Thomas Lister of Westby Hall, to which she pleaded not guilty. She had already appeared before Bromley in 1611, accused of murdering a child by witchcraft, but had been found not guilty. The most damning evidence given against her was that when she had been taken to see Lister's body, the corpse "bled fresh bloud presently, in the presence of all that were there present" after she touched it. According to a statement made to Nowell by James Device on 27 April, Jennet had attended the Malkin Tower meeting to seek help with Lister's murder. She was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging i ...

; her execution took place on 29 July on the Knavesmire

The Knavesmire is one of a number of large, marshy undeveloped areas within the city of York in North Yorkshire, England, which are collectively known as '' Strays''. Knavesmire, together with Hob Moor, comprises Micklegate Stray.

It has bee ...

, the present site of York Racecourse.

Lancaster Assizes, 18–19 August 1612

All the other accused lived in Lancashire, so they were sent to Lancaster Assizes for trial, where the judges were once again Altham and Bromley. The prosecutor was local magistrate Roger Nowell, who had been responsible for collecting the various statements and confessions from the accused. Nine-year-old Jennet Device was a key witness for the prosecution, something that would not have been permitted in many other 17th-century criminal trials. However, King James had made a case for suspending the normal rules of evidence for witchcraft trials in his ''Daemonologie''. As well as identifying those who had attended the Malkin Tower meeting, Jennet also gave evidence against her mother, brother, and sister.

Nine of the accused – Alizon Device, Elizabeth Device, James Device, Anne Whittle, Anne Redferne, Alice Nutter, Katherine Hewitt, John Bulcock and Jane Bulcock – were found guilty during the two-day trial and hanged at Gallows Hill in Lancaster on 20 August 1612; Elizabeth Southerns died while awaiting trial. Only one of the accused, Alice Grey, was found not guilty.

18 August

Anne Whittle (Chattox) was accused of the murder of Robert Nutter. She pleaded not guilty, but the confession she had made to Roger Nowell—likely under torture—was read out in court, and evidence against her was presented by James Robinson, who had lived with the Chattox family 20 years earlier. He claimed to remember that Nutter had accused Chattox of turning his beer sour, and that she was commonly believed to be a witch. Chattox broke down and admitted her guilt, calling on God for forgiveness and the judges to be merciful to her daughter, Anne Redferne.

Elizabeth Device was charged with the murders of James Robinson, John Robinson and, together with Alice Nutter and Demdike, the murder of Henry Mitton. Elizabeth Device vehemently maintained her innocence. Potts records that "this odious witch" suffered from a facial deformity resulting in her left eye being set lower than her right. The main witness against Device was her daughter, Jennet, who was about nine years old. When Jennet was brought into the courtroom and asked to stand up and give evidence against her mother, Elizabeth, confronted with her own child making accusations that would lead to her execution, began to curse and scream at her daughter, forcing the judges to have her removed from the courtroom before the evidence could be heard. Jennet was placed on a table and stated that she believed her mother had been a witch for three or four years. She also said her mother had a

All the other accused lived in Lancashire, so they were sent to Lancaster Assizes for trial, where the judges were once again Altham and Bromley. The prosecutor was local magistrate Roger Nowell, who had been responsible for collecting the various statements and confessions from the accused. Nine-year-old Jennet Device was a key witness for the prosecution, something that would not have been permitted in many other 17th-century criminal trials. However, King James had made a case for suspending the normal rules of evidence for witchcraft trials in his ''Daemonologie''. As well as identifying those who had attended the Malkin Tower meeting, Jennet also gave evidence against her mother, brother, and sister.

Nine of the accused – Alizon Device, Elizabeth Device, James Device, Anne Whittle, Anne Redferne, Alice Nutter, Katherine Hewitt, John Bulcock and Jane Bulcock – were found guilty during the two-day trial and hanged at Gallows Hill in Lancaster on 20 August 1612; Elizabeth Southerns died while awaiting trial. Only one of the accused, Alice Grey, was found not guilty.

18 August

Anne Whittle (Chattox) was accused of the murder of Robert Nutter. She pleaded not guilty, but the confession she had made to Roger Nowell—likely under torture—was read out in court, and evidence against her was presented by James Robinson, who had lived with the Chattox family 20 years earlier. He claimed to remember that Nutter had accused Chattox of turning his beer sour, and that she was commonly believed to be a witch. Chattox broke down and admitted her guilt, calling on God for forgiveness and the judges to be merciful to her daughter, Anne Redferne.

Elizabeth Device was charged with the murders of James Robinson, John Robinson and, together with Alice Nutter and Demdike, the murder of Henry Mitton. Elizabeth Device vehemently maintained her innocence. Potts records that "this odious witch" suffered from a facial deformity resulting in her left eye being set lower than her right. The main witness against Device was her daughter, Jennet, who was about nine years old. When Jennet was brought into the courtroom and asked to stand up and give evidence against her mother, Elizabeth, confronted with her own child making accusations that would lead to her execution, began to curse and scream at her daughter, forcing the judges to have her removed from the courtroom before the evidence could be heard. Jennet was placed on a table and stated that she believed her mother had been a witch for three or four years. She also said her mother had a familiar

In European folklore of the medieval and early modern periods, familiars (sometimes referred to as familiar spirits) were believed to be supernatural entities that would assist witches and cunning folk in their practice of magic. According to re ...

called Ball, who appeared in the shape of a brown dog. Jennet claimed to have witnessed conversations between Ball and her mother, in which Ball had been asked to help with various murders. James Device also gave evidence against his mother, saying he had seen her making a clay figure of one of her victims, John Robinson. Elizabeth Device was found guilty.

James Device pleaded not guilty to the murders by witchcraft of Anne Townley and John Duckworth. However he, like Chattox, had earlier made a confession to Nowell, which was read out in court. That, and the evidence presented against him by his sister Jennet, who said that she had seen her brother asking a black dog he had conjured up to help him kill Townley, was sufficient to persuade the jury to find him guilty.

19 August

The trials of the three Samlesbury witches

The Samlesbury witches were three women from the Lancashire village of Samlesbury – Jane Southworth, Jennet Bierley, and Ellen Bierley – accused by a 14-year-old girl, Grace Sowerbutts, of practising witchcraft. Their trial at Lan ...

were heard before Anne Redferne's first appearance in court, late in the afternoon, charged with the murder of Robert Nutter. The evidence against her was considered unsatisfactory, and she was acquitted.

Anne Redferne was not so fortunate the following day, when she faced her second trial, for the murder of Robert Nutter's father, Christopher, to which she pleaded not guilty. Demdike's statement to Nowell, which accused Anne of having made clay figures of the Nutter family, was read out in court. Witnesses were called to testify that Anne was a witch "more dangerous than her Mother". But she refused to admit her guilt to the end, and had given no evidence against any others of the accused. Anne Redferne was found guilty.

Jane Bulcock and her son John Bulcock, both from Newchurch in Pendle

Newchurch in Pendle is a village in the civil parish of Goldshaw Booth, Pendle, Lancashire, England, adjacent to Barley, to the south of Pendle Hill. It was formerly part of Roughlee Booth until its transferral in 1935.

History

Famous for the ...

, were accused and found guilty of the murder by witchcraft of Jennet Deane. Both denied that they had attended the meeting at Malkin Tower, but Jennet Device identified Jane as having been one of those present, and John as having turned the spit to roast the stolen sheep, the centrepiece of the Good Friday meeting at the Demdike's home.

Alice Nutter was unusual among the accused in being comparatively wealthy, the widow of a tenant yeoman

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of servants in an English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in mid-14th-century England. The 14th century also witn ...

farmer. She made no statement either before or during her trial, except to enter her plea of not guilty to the charge of murdering Henry Mitton by witchcraft. The prosecution alleged that she, together with Demdike and Elizabeth Device, had caused Mitton's death after he had refused to give Demdike a penny she had begged from him. The only evidence against Alice seems to have been that James Device claimed Demdike had told him of the murder, and Jennet Device in her statement said that Alice had been present at the Malkin Tower meeting. Alice may have called in on the meeting at Malkin Tower on her way to a secret (and illegal) Good Friday Catholic service, and refused to speak for fear of incriminating her fellow Catholics. Many of the Nutter family were Catholics, and two had been executed as Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

priests, John Nutter in 1584 and his brother Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

in 1600. Alice Nutter was found guilty.

Katherine Hewitt (a.k.a. Mould-Heeles) was charged and found guilty of the murder of Anne Foulds. She was the wife of a clothier from Colne

Colne () is a market town and civil parish in the Borough of Pendle in Lancashire, England. Located northeast of Nelson, north-east of Burnley, east of Preston and west of Leeds.

The town should not be confused with the unrelated Colne Val ...

, and had attended the meeting at Malkin Tower with Alice Grey. According to the evidence given by James Device, both Hewitt and Grey told the others at that meeting that they had killed a child from Colne, Anne Foulds. Jennet Device also picked Katherine out of a line-up, and confirmed her attendance at the Malkin Tower meeting.

Alice Grey was accused with Katherine Hewitt of the murder of Anne Foulds. Potts does not provide an account of Alice Grey's trial, simply recording her as one of the Samlesbury witches – which she was not, as she was one of those identified as having been at the Malkin Tower meeting – and naming her in the list of those found not guilty.

Alizon Device, whose encounter with John Law had triggered the events leading up to the trials, was charged with causing harm by witchcraft. Uniquely among the accused, Alizon was confronted in court by her alleged victim, John Law. She seems to have genuinely believed in her own guilt; when Law was brought into court Alizon fell to her knees in tears and confessed. She was found guilty.

''The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster''

Almost everything that is known about the trials comes from a report of the proceedings written by Thomas Potts, the clerk to the Lancaster Assizes. Potts was instructed to write his account by the trial judges, and had completed the work by 16 November 1612, when he submitted it for review. Bromley revised and corrected the manuscript before its publication in 1613, declaring it to be "truly reported" and "fit and worthie to be published".

Although written as an apparently verbatim account, ''The Wonderfull Discoverie'' is not a report of what was actually said at the trial but is instead reflecting what happened. Nevertheless, Potts "seems to give a generally trustworthy, although not comprehensive, account of an Assize witchcraft trial, provided that the reader is constantly aware of his use of written material instead of verbatim reports".

The trials took place not quite seven years after the

Almost everything that is known about the trials comes from a report of the proceedings written by Thomas Potts, the clerk to the Lancaster Assizes. Potts was instructed to write his account by the trial judges, and had completed the work by 16 November 1612, when he submitted it for review. Bromley revised and corrected the manuscript before its publication in 1613, declaring it to be "truly reported" and "fit and worthie to be published".

Although written as an apparently verbatim account, ''The Wonderfull Discoverie'' is not a report of what was actually said at the trial but is instead reflecting what happened. Nevertheless, Potts "seems to give a generally trustworthy, although not comprehensive, account of an Assize witchcraft trial, provided that the reader is constantly aware of his use of written material instead of verbatim reports".

The trials took place not quite seven years after the Gunpowder Plot

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in earlier centuries often called the Gunpowder Treason Plot or the Jesuit Treason, was a failed assassination attempt against King James I by a group of provincial English Catholics led by Robert Catesby who sought ...

to blow up the Houses of Parliament in an attempt to kill King James and the Protestant aristocracy had been foiled. It was alleged that the Pendle witches had hatched their own gunpowder plot to blow up Lancaster Castle, although historian Stephen Pumfrey has suggested that the "preposterous scheme" was invented by the examining magistrates and simply agreed to by James Device in his witness statement. It may therefore be significant that Potts dedicated ''The Wonderfull Discoverie'' to Thomas Knyvet and his wife Elizabeth; Knyvet was the man credited with apprehending Guy Fawkes

Guy Fawkes (; 13 April 1570 – 31 January 1606), also known as Guido Fawkes while fighting for the Spanish, was a member of a group of provincial English Catholics involved in the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605. He was born and educated ...

and thus saving the King.

Modern interpretation

It has been estimated that all the English witch trials between the early 15th and early 18th centuries resulted in fewer than 500 executions, so this one series of trials in July and August 1612 accounts for more than two per cent of that total. Court records show that Lancashire was unusual in the north of England for the frequency of its witch trials. NeighbouringCheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's county t ...

, for instance, also suffered from economic problems and religious activists, but there only 47 people were indicted for causing harm by witchcraft between 1589 and 1675, of whom 11 were found guilty.

Pendle was part of the parish of Whalley, an area covering , too large to be effective in preaching and teaching the doctrines of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

: both the survival of Catholicism and the upsurge of witchcraft in Lancashire have been attributed to its over-stretched parochial structure. Until its dissolution

Dissolution may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Books

* ''Dissolution'' (''Forgotten Realms'' novel), a 2002 fantasy novel by Richard Lee Byers

* ''Dissolution'' (Sansom novel), a 2003 historical novel by C. J. Sansom Music

* Dissolution, in mu ...

, the spiritual needs of the people of Pendle and surrounding districts had been served by nearby Whalley Abbey

Whalley Abbey is a former Cistercian abbey in Whalley, Lancashire, England. After the dissolution of the monasteries, the abbey was largely demolished and a country house was built on the site. In the 20th century the house was modified ...

, but its closure in 1537 left a moral vacuum.

Many of the allegations made in the Pendle witch trials resulted from members of the Demdike and Chattox families making accusations against each other. Historian John Swain has said that the outbreaks of witchcraft in and around Pendle demonstrate the extent to which people could make a living either by posing as a witch, or by accusing or threatening to accuse others of being a witch. Although it is implicit in much of the literature on witchcraft that the accused were victims, often mentally or physically abnormal, for some at least, it may have been a trade like any other, albeit one with significant risks. There may have been bad blood between the Demdike and Chattox families because they were in competition with each other, trying to make a living from healing, begging, and extortion. The Demdikes are believed to have lived close to Newchurch in Pendle, and the Chattox family about away, near the village of Fence

A fence is a structure that encloses an area, typically outdoors, and is usually constructed from posts that are connected by boards, wire, rails or netting. A fence differs from a wall in not having a solid foundation along its whole length.

...

.

Aftermath and legacy

Altham continued with his judicial career until his death in 1617, and Bromley achieved his desired promotion to the Midlands Circuit in 1616. Potts was given the keepership of Skalme Park by James in 1615, to breed and train the king's hounds. In 1618, he was given responsibility for "collecting the forfeitures on the laws concerning sewers, for twenty-one years". Having played her part in the deaths of her mother, brother, and sister, Jennet Device may eventually have found herself accused of witchcraft. A woman with that name was listed in a group of 20 tried at Lancaster Assizes on 24 March 1634, although it cannot be certain that it was the same Jennet Device. The charge against her was the murder of Isabel Nutter, William Nutter's wife. In that series of trials the chief prosecution witness was a ten-year-old boy,

Altham continued with his judicial career until his death in 1617, and Bromley achieved his desired promotion to the Midlands Circuit in 1616. Potts was given the keepership of Skalme Park by James in 1615, to breed and train the king's hounds. In 1618, he was given responsibility for "collecting the forfeitures on the laws concerning sewers, for twenty-one years". Having played her part in the deaths of her mother, brother, and sister, Jennet Device may eventually have found herself accused of witchcraft. A woman with that name was listed in a group of 20 tried at Lancaster Assizes on 24 March 1634, although it cannot be certain that it was the same Jennet Device. The charge against her was the murder of Isabel Nutter, William Nutter's wife. In that series of trials the chief prosecution witness was a ten-year-old boy, Edmund Robinson

Edmund Robinson was an English ten-year-old boy from Wheatley Lane, Lancashire, who sparked a witch-hunt.

His story was the inspiration for the 1634 play '' The Late Lancashire Witches''.''Devil Dogs'', p. 26, May 2011, BBC History Magazine

...

. All but one of the accused were found guilty, but the judges refused to pass death sentences, deciding instead to refer the case to the king, Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

. Under cross-examination in London, Robinson admitted that he had fabricated his evidence, but even though four of the accused were eventually pardoned, they all remained incarcerated in Lancaster Gaol, where it is likely that they died. An official record dated 22 August 1636 lists Jennet Device as one of those still held in the prison. These later Lancashire witchcraft trials were the subject of a contemporary play written by Thomas Heywood

Thomas Heywood (early 1570s – 16 August 1641) was an English playwright, actor, and author. His main contributions were to late Elizabethan and early Jacobean theatre. He is best known for his masterpiece ''A Woman Killed with Kindness'', a ...

and Richard Brome

Richard Brome ; (c. 1590? – 24 September 1652) was an English dramatist of the Caroline era.

Life

Virtually nothing is known about Brome's private life. Repeated allusions in contemporary works, like Ben Jonson's ''Bartholomew Fair'', ind ...

, ''The Late Lancashire Witches

''The Late Lancashire Witches'' is a Caroline-era stage play and written by Thomas Heywood and Richard Brome, published in 1634. The play is a topical melodrama on the subject of the witchcraft controversy that arose in Lancashire in 1633.

Perfo ...

''.

In modern times the witches have become the inspiration for Pendle's tourism and heritage industries, with local shops selling a variety of witch-motif gifts. Burnley

Burnley () is a town and the administrative centre of the wider Borough of Burnley in Lancashire, England, with a 2001 population of 73,021. It is north of Manchester and east of Preston, at the confluence of the River Calder and River Bru ...

's Moorhouse's produces a beer called Pendle Witches Brew, and there is a Pendle Witch Trail running from Pendle Heritage Centre to Lancaster Castle, where the accused witches were held before their trial. The X43 bus route run by Burnley Bus Company

The Burnley Bus Company operates both local and regional bus services in Greater Manchester and Lancashire, England. It is a subsidiary of Transdev Blazefield, which operates bus services across Greater Manchester, Lancashire, North Yorkshire a ...

has been branded The Witch Way

The Witch Way is the branding for long-standing English bus route X43, which runs between Burnley and Manchester. The service is currently operated by Burnley Bus Company.

The route has operated continuously since 1948. It was previously oper ...

, with some of the vehicles operating on it named after the witches in the trial. Pendle Hill, which dominates the landscape of the area, continues to be associated with witchcraft, and hosts a hilltop gathering every Halloween

Halloween or Hallowe'en (less commonly known as Allhalloween, All Hallows' Eve, or All Saints' Eve) is a celebration observed in many countries on 31 October, the eve of the Western Christian feast of All Saints' Day. It begins the observanc ...

.

Scholar Catherine Spooner argues in an article for ''Hellebore'' magazine that with the 400-year anniversary of the Pendle witch trials, the notion of the witches as folk heroes caught the popular imagination. With new cultural productions revisiting the witches' story (Mary Sharratt's ''Daughters of the WItching Hill'' (2011) or Jeanette Winterson

Jeanette Winterson (born 27 August 1959) is an English writer. Her first book, '' Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit'', was a semi-autobiographical novel about a sensitive teenage girl rebelling against convention. Other novels explore gender pola ...

's ''The Daylight Gate'' (2012)), Spooner argues that the Pendle witches have been transformed from "folk devil to folk heroes", and that "their history has become a model of resistance for the disenchanted and disenfranchised".

A petition was presented to UK Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

Jack Straw

John Whitaker Straw (born 3 August 1946) is a British politician who served in the Cabinet from 1997 to 2010 under the Labour governments of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. He held two of the traditional Great Offices of State, as Home Secretary ...

in 1998 asking for the witches to be pardoned, but it was decided that their convictions should stand. Ten years later another petition was organised in an attempt to obtain pardons for Chattox and Demdike. The later petition followed the Swiss government's pardon earlier that year of Anna Göldi

Anna Göldi (also Göldin or Goeldin, 24 October 1734 – 13 June 1782) was an 18th-century Swiss housemaid who was one of the last persons to be executed for witchcraft in Europe. Göldi, who was executed by decapitation in Glarus, has been ...

, beheaded in 1782, thought to be the last person in Europe to be executed as a witch.

Literary adaptations and other media

Victorian novelistWilliam Harrison Ainsworth

William Harrison Ainsworth (4 February 18053 January 1882) was an English historical novelist born at King Street in Manchester. He trained as a lawyer, but the legal profession held no attraction for him. While completing his legal studies in ...

wrote a romanticised account of the Pendle witches: ''The Lancashire Witches

''The Lancashire Witches'' is the only one of William Harrison Ainsworth's forty novels that has remained continuously in print since its first publication. It was serialised in the ''Sunday Times'' newspaper in 1848; a book edition appeared the ...

'', first published in 1849, is the only one of his 40 novels never to have been out of print

__NOTOC__

An out-of-print (OOP) or out-of-commerce item or work is something that is no longer being published. The term applies to all types of printed matter, visual media, sound recordings, and video recordings. An out-of-print book is a book ...

. The British writer Robert Neill dramatised the events of 1612 in his novel ''Mist over Pendle'', first published in 1951. The writer and poet Blake Morrison

Philip Blake Morrison FRSL (born 8 October 1950) is an English poet and author who has published in a wide range of fiction and non-fiction genres. His greatest success came with the publication of his memoirs ''And When Did You Last See Your Fat ...

treated the subject in his suite of poems ''Pendle Witches'', published in 1996. Poet Simon Armitage

Simon Robert Armitage (born 26 May 1963) is an English poet, playwright, musician and novelist. He was appointed Poet Laureate on 10 May 2019. He is professor of poetry at the University of Leeds.

He has published over 20 collections of poetr ...

narrated a 2011 documentary on BBC Four

BBC Four is a British free-to-air public broadcast television channel owned and operated by the BBC. It was launched on 2 March 2002

, ''The Pendle Witch Child''.

The novel ''Good Omens

''Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch'' is a 1990 novel written as a collaboration between the English authors Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman.

The book is a comedy about the birth of the son of Satan and the c ...

'' by Terry Pratchett

Sir Terence David John Pratchett (28 April 1948 – 12 March 2015) was an English humourist, satirist, and author of fantasy novels, especially comical works. He is best known for his ''Discworld'' series of 41 novels.

Pratchett's first nov ...

and Neil Gaiman

Neil Richard MacKinnon GaimanBorn as Neil Richard Gaiman, with "MacKinnon" added on the occasion of his marriage to Amanda Palmer. ; ( Neil Richard Gaiman; born 10 November 1960) is an English author of short fiction, novels, comic books, gr ...

(later adapted for television) features several witch characters named after the original Pendle witches, including Agnes Nutter, a prophet burned at the stake, and her descendant Anathema Device. Gaiman confirmed the homage in a 2016 tweet.

The novel ''The Familiars'' (2019) by Stacey Halls includes historical figures as characters in a story that is based at the time of the Pendle witch trials. The story focusses on Fleetwood Shuttleworth, a noblewoman who becomes pregnant at the age of seventeen, and becomes involved in the trial of her midwife

A midwife is a health professional who cares for mothers and newborns around childbirth, a specialization known as midwifery.

The education and training for a midwife concentrates extensively on the care of women throughout their lifespan; co ...

Alice Gray who is accused of witchcraft.

2012 anniversary

Events to mark the 400th anniversary of the trials in 2012 included an exhibition, "A Wonderful Discoverie: Lancashire Witches 1612–2012", atGawthorpe Hall

Gawthorpe Hall is an Elizabethan country house on the banks of the River Calder, in Ightenhill, a civil parish in the Borough of Burnley, Lancashire, England. Its estate extends into Padiham, with the Stockbridge Drive entrance situated there. ...

staged by Lancashire County Council

Lancashire County Council is the upper-tier local authority for the non-metropolitan county of Lancashire, England. It consists of 84 councillors. Since the 2017 election, the council has been under Conservative control.

Prior to the 2009 La ...

. ''The Fate of Chattox'', a piece by David Lloyd-Mostyn for clarinet and piano, taking its theme from the events leading to Chattox's demise, was performed by Aquilon at the Chorlton Arts Festival.

A life-size statue of Alice Nutter, by sculptor David Palmer, was unveiled in her home village, Roughlee

Roughlee is a village in Borough of Pendle, Pendle, Lancashire, England, in the civil parishes in England, civil parish of Roughlee Booth. It is close to Nelson, Lancashire, Nelson, Barrowford and Blacko. The village lies at the foot of Pendle ...

. In August, a world record for the largest group dressed as witches was set by 482 people who walked up Pendle Hill, on which the date "1612" had been installed in 400-foot-tall numbers by artist Philippe Handford using horticultural fleece

Horticultural fleece is a thin, nonwoven, polypropylene fabric which is used as a floating mulch to protect both late and early crops and delicate plants from cold weather and frost, as well as insect pests during the normal growing season. It admi ...

. The Bishop of Burnley, the Rt Rev John Goddard John Goddard may refer to:

* John Goddard (engraver) (fl. 1645–1671), engraver

*John Goddard (cricketer) (1919–1987), West Indian cricketer

*Johnathan Goddard (1981–2008), American football player

*John Goddard (adventurer)

John Goddard (Ju ...

, had objected to the appearance of the numerals, as what he saw as a "light-hearted" celebration of "injustice and oppression".

Publications in 2012 inspired by the trials include two novellas, ''The Daylight Gate'' by Jeanette Winterson

Jeanette Winterson (born 27 August 1959) is an English writer. Her first book, '' Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit'', was a semi-autobiographical novel about a sensitive teenage girl rebelling against convention. Other novels explore gender pola ...

and ''Malkin Child'' by Livi Michael

Livi Michael, also known as Olivia Michael (15 March 1960, Manchester), is a British fiction writer who publishes children and adult novels.

Career

Michael began writing poetry at the age of seven. She attended Tameside College of Technolog ...

. Blake Morrison

Philip Blake Morrison FRSL (born 8 October 1950) is an English poet and author who has published in a wide range of fiction and non-fiction genres. His greatest success came with the publication of his memoirs ''And When Did You Last See Your Fat ...

published a volume of poetry, ''A Discoverie of Witches''.

See also

*Bideford witch trial

The Bideford witch trial resulted in hangings for witchcraft in England. Temperance Lloyd, Mary Trembles and Susannah Edwards from the town of Bideford in Devon were tried in 1682 at the Exeter Assizes at Rougemont Castle. Much of the evidence a ...

* Cunning folk

Cunning folk, also known as folk healers or wise folk, were practitioners of folk medicine, helpful folk magic and divination in Europe from the Middle Ages until the 20th century. Their practices were known as the cunning craft. Their services a ...

References

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * (Facsimile reprint of Davies' 1929 book, containing the text of ''The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster'' by Potts, Thomas (1613)) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * *External links

* (1597) * (1849) * (1613) {{featured article History of Lancashire People executed for witchcraft 1612 in law 1612 in England 17th-century trials Borough of Pendle Lancashire folklore 17th-century executions by England People executed by Stuart England Witch trials in England