Encyclopædia Britannica

The ( Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various ...

''.

Swinburne wrote about many taboo

A taboo or tabu is a social group's ban, prohibition, or avoidance of something (usually an utterance or behavior) based on the group's sense that it is excessively repulsive, sacred, or allowed only for certain persons.''Encyclopædia Britannic ...

topics, such as lesbianism, sado-masochism

Sadomasochism ( ) is the giving and receiving of pleasure from acts involving the receipt or infliction of pain or humiliation. Practitioners of sadomasochism may seek sexual pleasure from their acts. While the terms sadist and masochist refer ...

, and anti-theism

Antitheism, also spelled anti-theism, is the philosophical position that theism should be opposed. The term has had a range of applications. In secular contexts, it typically refers to direct opposition to the belief in any deity.

Etymology

The ...

. His poems have many common motifs, such as the ocean, time, and death. Several historical people are featured in his poems, such as Sappho ("Sapphics"), Anactoria ("Anactoria"), and Catullus

Gaius Valerius Catullus (; 84 - 54 BCE), often referred to simply as Catullus (, ), was a Latin poetry, Latin poet of the late Roman Republic who wrote chiefly in the neoteric style of poetry, focusing on personal life rather than classical h ...

("To Catullus").

Biography

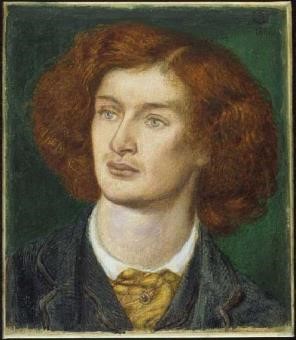

Swinburne was born at 7 Chester Street, Grosvenor Place, London, on 5 April 1837. He was the eldest of six children born to Captain (later Admiral) Charles Henry Swinburne (1797–1877) and Lady Jane Henrietta, daughter of the 3rd Earl of Ashburnham, a wealthy Northumbrian family. He grew up at East Dene in Bonchurch on the

Swinburne was born at 7 Chester Street, Grosvenor Place, London, on 5 April 1837. He was the eldest of six children born to Captain (later Admiral) Charles Henry Swinburne (1797–1877) and Lady Jane Henrietta, daughter of the 3rd Earl of Ashburnham, a wealthy Northumbrian family. He grew up at East Dene in Bonchurch on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a Counties of England, county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the List of islands of England#Largest islands, largest and List of islands of England#Mo ...

. The Swinburnes also had a London home at Whitehall Gardens, Westminster.

As a child, Swinburne was "nervous" and "frail," but "was also fired with nervous energy and fearlessness to the point of being reckless."

Swinburne attended Eton College

Eton College () is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI of England, Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. i ...

(1849–53), where he started writing poetry. At Eton, he won first prizes in French and Italian. He attended Balliol College, Oxford (1856–60) with a brief hiatus when he was rusticated from the university in 1859 for having publicly supported the attempted assassination of Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A neph ...

by Felice Orsini. He returned in May 1860, though he never received a degree.

Swinburne spent summer holidays at Capheaton Hall

Capheaton Hall, near Wallington, Northumberland, is an English country house, the seat of the Swinburne Baronets and a childhood home of the poet Algernon Swinburne. It counts among the principal gentry seats of Northumberland. It is a Grade ...

in Northumberland

Northumberland () is a ceremonial counties of England, county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Ab ...

, the house of his grandfather, Sir John Swinburne, 6th Baronet (1762–1860), who had a famous library and was president of the Literary and Philosophical Society in Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is a ...

. Swinburne considered Northumberland to be his native county, an emotion reflected in poems like the intensely patriotic "Northumberland", " Grace Darling" and others. He enjoyed riding his pony across the moors, he was a daring horseman, "through honeyed leagues of the northland border", as he called the Scottish border in his ''Recollections''.

In the period 1857–60, Swinburne became a member of Lady Trevelyan's intellectual circle at Wallington Hall.

After his grandfather's death in 1860 he stayed with

In the period 1857–60, Swinburne became a member of Lady Trevelyan's intellectual circle at Wallington Hall.

After his grandfather's death in 1860 he stayed with William Bell Scott

William Bell Scott (1811–1890) was a Scottish artist in oils and watercolour and occasionally printmaking. He was also a poet and art teacher, and his posthumously published reminiscences give a chatty and often vivid picture of life in the ...

in Newcastle. In 1861, Swinburne visited Menton

Menton (; , written ''Menton'' in classical norm or ''Mentan'' in Mistralian norm; it, Mentone ) is a commune in the Alpes-Maritimes department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region on the French Riviera, close to the Italian border.

Me ...

on the French Riviera

The French Riviera (known in French as the ; oc, Còsta d'Azur ; literal translation "Azure Coast") is the Mediterranean coastline of the southeast corner of France. There is no official boundary, but it is usually considered to extend from ...

, staying at the Villa Laurenti to recover from the excessive use of alcohol. From Menton, Swinburne travelled to Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, where he journeyed extensively. In December 1862, Swinburne accompanied Scott and his guests, probably including Dante Gabriel Rossetti, on a trip to Tynemouth

Tynemouth () is a coastal town in the metropolitan borough of North Tyneside, North East England. It is located on the north side of the mouth of the River Tyne, hence its name. It is 8 mi (13 km) east-northeast of Newcastle upon Tyne ...

. Scott writes in his memoirs that, as they walked by the sea, Swinburne declaimed the as yet unpublished " Hymn to Proserpine" and "Laus Veneris" in his lilting intonation, while the waves "were running the whole length of the long level sands towards Cullercoats and sounding like far-off acclamations".

At Oxford, Swinburne met several

At Oxford, Swinburne met several Pre-Raphaelites

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (later known as the Pre-Raphaelites) was a group of English painters, poets, and art critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, Jam ...

, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti. He also met William Morris. After leaving college, he lived in London and started an active writing career, where Rossetti was delighted with his "little Northumbrian friend", probably a reference to Swinburne's diminutive height—he was just five-foot-four.

Swinburne was an alcoholic

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol that results in significant mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognized diagnostic entity. Predomina ...

and algolagniac and highly excitable. He liked to be flogged. His health suffered, and in 1879 at the age of 42, he was taken into care by his friend, Theodore Watts-Dunton

Theodore Watts-Dunton (12 October 1832 – 6 June 1914), from St Ives, Huntingdonshire, was an English poetry critic with major periodicals, and himself a poet. He is remembered particularly as the friend and minder of Algernon Charles Swinbu ...

, who looked after him for the rest of his life at The Pines, 11 Putney Hill, Putney

Putney () is a district of southwest London, England, in the London Borough of Wandsworth, southwest of Charing Cross. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London.

History

Putney is an ancient pa ...

. Watts-Dunton took him to the lost town of Dunwich, on the Suffolk coast, on several occasions in the 1870s.

In Watts-Dunton's care Swinburne lost his youthful rebelliousness and developed into a figure of social respectability. It was said of Watts-Dunton that he saved the man and killed the poet. Swinburne died at the Pines on 10 April 1909, at the age of 72, and was buried at St. Boniface Church, Bonchurch

St Boniface Church, Bonchurch is a parish church in the Church of England located in Bonchurch, Isle of Wight.

History

The church dates from 1847 and 1848 by the architect Ferrey.''The Buildings of England, Hampshire and the Isle of Wight''. ...

on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a Counties of England, county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the List of islands of England#Largest islands, largest and List of islands of England#Mo ...

.

Work

Swinburne's poetic works include: ''

Swinburne's poetic works include: ''Atalanta in Calydon

Atalanta (; grc-gre, Ἀταλάντη, Atalantē) meaning "equal in weight", is a heroine in Greek mythology.

There are two versions of the huntress Atalanta: one from Arcadia, whose parents were Iasus and Clymene and who is primarily known ...

'' (1865), '' Poems and Ballads'' (1866), ''Songs before Sunrise

''Songs before Sunrise'' is a collection of poems relating to Italy, and particularly its unification, by Algernon Charles Swinburne. It was published in 1871 and can be seen as an extension of his earlier long poem, " A Song of Italy". Swinburn ...

'' (1871), ''Poems and Ballads Second Series

Poetry (derived from the Greek '' poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings ...

'', (1878) '' Tristram of Lyonesse'' (1882), '' Poems and Ballads Third Series'' (1889), and the novel '' Lesbia Brandon'' (published posthumously in 1952).

'' Poems and Ballads'' caused a sensation when it was first published, especially the poems written in homage of Sappho of Lesbos such as " Anactoria" and " Sapphics": Moxon and Co. transferred its publication rights to John Camden Hotten. Other poems in this volume such as "The Leper," "Laus Veneris," and "St Dorothy" evoke a Victorian fascination with the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, and are explicitly mediaeval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

in style, tone and construction. Also featured in this volume are " Hymn to Proserpine", " The Triumph of Time" and " Dolores (Notre-Dame des Sept Douleurs)".

Swinburne wrote in a wide variety of forms, including Sapphic stanzas (comprising 3 hendecasyllabic lines followed by an Adonic):

Swinburne devised the poetic form called the roundel

A roundel is a circular disc used as a symbol. The term is used in heraldry, but also commonly used to refer to a type of national insignia used on military aircraft, generally circular in shape and usually comprising concentric rings of diffe ...

, a variation of the French Rondeau form, and some were included in ''A Century of Roundels'' dedicated to Christina Rossetti. Swinburne wrote to Edward Burne-Jones

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, 1st Baronet, (; 28 August, 183317 June, 1898) was a British painter and designer associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood which included Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Millais, Ford Madox Brown and Holman ...

in 1883: "I have got a tiny new book of songs or songlets, in one form and all manner of metres ... just coming out, of which Miss Rossetti has accepted the dedication. I hope you and Georgie '' is wife Georgiana, one of the MacDonald sisters">MacDonald_sisters.html" ;"title="is wife Georgiana, one of the MacDonald sisters">is wife Georgiana, one of the MacDonald sisters' will find something to like among a hundred poems of nine lines each, twenty-four of which are about babies or small children". Opinions of these poems vary between those who find them captivating and brilliant, to those who find them merely clever and contrived. One of them, ''A Baby's Death'', was set to music by the English composer Sir Edward Elgar as the song "Roundel: The little eyes that never knew Light". English composer Mary Augusta Wakefield set Swinburne's work ''May Time in Midwinter'' to music as well.

Swinburne was influenced by the work of William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

, Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley ( ; 4 August 17928 July 1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets. A radical in his poetry as well as in his political and social views, Shelley did not achieve fame during his lifetime, but recognition of his ach ...

, Catullus

Gaius Valerius Catullus (; 84 - 54 BCE), often referred to simply as Catullus (, ), was a Latin poetry, Latin poet of the late Roman Republic who wrote chiefly in the neoteric style of poetry, focusing on personal life rather than classical h ...

, William Morris, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Robert Browning, Alfred Lord Tennyson, and Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

. Swinburne was popular in England during his life, but his influence has greatly decreased since his death.

After the first ''Poems and Ballads'', Swinburne's later poetry increasingly was devoted to celebrations of republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

and revolutionary causes, particularly in the volume ''Songs before Sunrise

''Songs before Sunrise'' is a collection of poems relating to Italy, and particularly its unification, by Algernon Charles Swinburne. It was published in 1871 and can be seen as an extension of his earlier long poem, " A Song of Italy". Swinburn ...

''. "A Song of Italy" is dedicated to Mazzini; "Ode on the Proclamation of the French Republic" is dedicated to Victor Hugo; and "Dirae" is a sonnet sequence of vituperative attacks against those whom Swinburne believed to be enemies of liberty. ''Erechtheus'' is the culmination of Swinburne's republican verse.

He did not stop writing love poetry entirely, including his great epic-length poem ''Tristram of Lyonesse'', but its content is much less shocking than those of his earlier love poetry. His versification, and especially his rhyming technique, remain in top form to the end.

Reception

Swinburne is considered a poet of the decadent school. Swinburne's verses dealing withsadomasochism

Sadomasochism ( ) is the giving and receiving of pleasure from acts involving the receipt or infliction of pain or humiliation. Practitioners of sadomasochism may seek sexual pleasure from their acts. While the terms sadist and masochist refer ...

, lesbianism and other taboo subjects often attracted Victorian ire, and led to him becoming persona non grata in high society . Rumours about his perversions often filled the broadsheets, and he ironically used to play along, confessing to being a pederast and having sex with monkeys.

In France, Swinburne was highly praised by Stéphane Mallarmé, and was invited to contribute to a book in honour of the poet Théophile Gautier

Pierre Jules Théophile Gautier ( , ; 30 August 1811 – 23 October 1872) was a French poet, dramatist, novelist, journalist, and art and literary critic.

While an ardent defender of Romanticism, Gautier's work is difficult to classify and rem ...

, ''Le tombeau de Théophile Gautier'' (Wikisource

Wikisource is an online digital library of free-content textual sources on a wiki, operated by the Wikimedia Foundation. Wikisource is the name of the project as a whole and the name for each instance of that project (each instance usually ...

): he answered by six poems in French, English, Latin and Greek.

H. P. Lovecraft considered Swinburne "the only real poet in either England or America after the death of Mr. Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is wide ...

."

Renee Vivien, the English poetess, was highly impressed with Swinburne and often included quotes of him in her works.

T. S. Eliot

Thomas Stearns Eliot (26 September 18884 January 1965) was a poet, essayist, publisher, playwright, literary critic and editor.Bush, Ronald. "T. S. Eliot's Life and Career", in John A Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (eds), ''American National Biogr ...

read Swinburne's essays on the Shakespearean and Jonsonian dramatists in ''The Contemporaries of Shakespeare'' and ''The Age of Shakespeare'' and Swinburne's books on Shakespeare and Jonson. Writing on Swinburne in ''The Sacred Wood: Essays on Poetry and Criticism'', Eliot wrote Swinburne had mastered his material, and "he is a more reliable guide to hese dramatiststhan Hazlitt, Coleridge, or Lamb

Lamb or The Lamb may refer to:

* A young sheep

* Lamb and mutton, the meat of sheep

Arts and media Film, television, and theatre

* ''The Lamb'' (1915 film), a silent film starring Douglas Fairbanks Sr. in his screen debut

* ''The Lamb'' (1918 ...

: and his perception of relative values is almost always correct". Eliot wrote that Swinburne, as a poet, "mastered his technique, which is a great deal, but he did not master it to the extent of being able to take liberties with it, which is everything." Furthermore, Eliot disliked Swinburne's prose, about which he wrote "the tumultuous outcry of adjectives, the headstrong rush of undisciplined sentences, are the index to the impatience and perhaps laziness of a disorderly mind.".

Swinburne was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, caption =

, awarded_for = Outstanding contributions in literature

, presenter = Swedish Academy

, holder = Annie Ernaux (2022)

, location = Stockholm, Sweden

, year = 1901 ...

every year from 1903 to 1909. In 1908 he was one of the main candidates considered for the prize, and was nominated again in 1909.Wilhelm Odelberg, ''Nobel: The Man and His Prizes'', p. 97.

Verse drama

*''The Queen Mother'' (1860) *''Rosamond'' (1860) *''Chastelard'' (1865) *''Bothwell'' (1874) *''Mary Stuart'' (1881) *''Marino Faliero'' (1885) *''Locrine'' (1887) *''The Sisters'' (1892) *''Rosamund, Queen of the Lombards'' (1899)Prose drama

*''La Soeur de la reine

''La Soeur de la reine'' is a burlesque French-language play written by Algernon Charles Swinburne in the 1860s. The comedy of the piece derives from its parody of the full-bloodedly Romantic style of Victor Hugo's prose plays, and from its p ...

'' (published posthumously 1964)

Poetry

*''Atalanta in Calydon'' (1865) *'' Poems and Ballads'' (1866) *''Songs Before Sunrise

''Songs before Sunrise'' is a collection of poems relating to Italy, and particularly its unification, by Algernon Charles Swinburne. It was published in 1871 and can be seen as an extension of his earlier long poem, " A Song of Italy". Swinburn ...

'' (1871)

*'' Songs of Two Nations'' (1875)

*''Erechtheus'' (1876)

*'' Poems and Ballads, Second Series'' (1878)

*'' Songs of the Springtides'' (1880)

*'' Studies in Song'' (1880)

*''The Heptalogia, or the Seven against Sense. A Cap with Seven Bells'' (1880)

*'' Tristram of Lyonesse'' (1882)

*'' A Century of Roundels'' (1883)

*'' A Midsummer Holiday and Other Poems'' (1884)

*'' Poems and Ballads, Third Series'' (1889)

*'' Astrophel and Other Poems'' (1894)

*'' The Tale of Balen'' (1896)

*'' A Channel Passage and Other Poems'' (1904)

:Although formally tragedies, ''Atalanta in Calydon'' and ''Erechtheus'' are traditionally included with "poetry".

Criticism

*'' William Blake: A Critical Essay'' (1868, new edition 1906) *'' Under the Microscope'' (1872) *'' George Chapman: A Critical Essay'' (1875) *'' Essays and Studies'' (1875) *'' A Note on Charlotte Brontë'' (1877) *'' A Study of Shakespeare'' (1880) *'' A Study of Victor Hugo'' (1886) *'' A Study of Ben Johnson'' (1889) *''Studies in Prose and Poetry'' (1894) *'' The Age of Shakespeare'' (1908) *''Shakespeare'' (1909)Major collections

*''The poems of Algernon Charles Swinburne'', 6 vols. London: Chatto & Windus, 1904. *''The Tragedies of Algernon Charles Swinburne'', 5 vols. London: Chatto & Windus, 1905. *''The Complete Works of Algernon Charles Swinburne'', ed. Sir Edmund Gosse and Thomas James Wise, 20 vols. Bonchurch Edition; London and New York: William Heinemann and Gabriel Wells, 1925–7. *''The Swinburne Letters'', ed. Cecil Y. Lang, 6 vols. 1959–62. *''Uncollected Letters of Algernon Charles Swinburne'', ed. Terry L. Meyers, 3 vols. 2004.Ancestry

See also

*'' Patience, or Bunthorne's Bride'' (1881), a Gilbert-and-Sullivan opera that satirizes Swinburne and his poetry *'' Poems and Ballads'' * Decadent movement *'' Tristram of Lyonesse''References

*Sources

* Leith, Mrs. Disney. (1917), ''Algernon Charles Swinburne, Personal Recollections by his Cousin'' - With excerpts from some of his personal letters. London and New York : G. P. Putnam's Sons. * Swinburne, Algernon (1919), Gosse, Edmund; Wise, Thomas, eds.,The Letters of Algernon Charles Swinburne

', Volumes 1–6, New York: John Lane Company. * * Rooksby, Rikky (1997) ''A C Swinburne: A Poet's Life''. Aldershot: Scolar Press. * Louis, Margot Kathleen (1990) ''Swinburne and His Gods: the Roots and Growth of an Agnostic Poetry''. Mcgill-Queens University Press. * McGann, Jerome (1972) ''Swinburne: An Experiment in Criticism''. University of Chicago Press. * Peters, Robert (1965) ''The Crowns of Apollo: Swinburne's Principles of Literature and Art: a Study in Victorian Criticism and Aesthetics''. Wayne State University Press. * * Wakeling, E; Hubbard, T; Rooksby, R (2008) ''Lewis Carroll, Robert Louis Stevenson and Algernon Charles Swinburne by their contemporaries''. London: Pickering & Chatto, 3 vols. * * *

External links

* Poetry oAlgernon Charles Swinburne

at the Poetry Foundation.

in

T. S. Eliot

Thomas Stearns Eliot (26 September 18884 January 1965) was a poet, essayist, publisher, playwright, literary critic and editor.Bush, Ronald. "T. S. Eliot's Life and Career", in John A Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (eds), ''American National Biogr ...

's essay "Imperfect Critics", collected in ''The Sacred Wood: Essays on Poetry and Criticism'', 1922.

*

Swinburne

a eulogy by A. E. Housman

Stirnet: Swinburne02

Swinburne's genealogy.

No. 2. The Pines

Max Beerbohm

Sir Henry Maximilian Beerbohm (24 August 1872 – 20 May 1956) was an English essayist, Parody, parodist and Caricature, caricaturist under the signature Max. He first became known in the 1890s as a dandy and a humorist. He was the drama critic ...

's memoir of Swinburne.

The Swinburne Project

A digital archive of the life and works of Algernon Charles Swinburne. * (plain text and HTML) * * Archival material at

Algernon Charles Swinburne Collection

at the

Harry Ransom Center

The Harry Ransom Center (until 1983 the Humanities Research Center) is an archive, library and museum at the University of Texas at Austin, specializing in the collection of literary and cultural artifacts from the Americas and Europe for the pu ...

* Algernon Swinburne Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Swinburne, Algernon

1837 births

1909 deaths

People from Westminster

Artists' Rifles soldiers

19th-century English poets

People educated at Eton College

Victorian poets

English male poets

British erotica writers

Writers from London