Alfred Wegener on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alfred Lothar Wegener (; ; 1 November 1880 – November 1930) was a German

In April-October 1929, Wegener embarked on his third expedition to Greenland, which laid the groundwork for the main expedition which he was planning to lead in 1930-1931.

Wegener's last Greenland expedition was in 1930. The 14 participants under his leadership were to establish three permanent stations from which the thickness of the Greenland ice sheet could be measured and year-round Arctic weather observations made.

They would travel on the ice cap using two innovative, propeller-driven

In April-October 1929, Wegener embarked on his third expedition to Greenland, which laid the groundwork for the main expedition which he was planning to lead in 1930-1931.

Wegener's last Greenland expedition was in 1930. The 14 participants under his leadership were to establish three permanent stations from which the thickness of the Greenland ice sheet could be measured and year-round Arctic weather observations made.

They would travel on the ice cap using two innovative, propeller-driven  On 24 September, although the route markers were by now largely buried under snow, Wegener set out with thirteen Greenlanders and his meteorologist Fritz Loewe to supply the camp by dog sled. During the journey, the temperature reached and Loewe's toes became so frostbitten they had to be amputated with a penknife without anaesthetic. Twelve of the Greenlanders returned to West camp. On 19 October the remaining three members of the expedition reached '.

Expedition member Johannes Georgi estimated that there were only enough supplies for three at ', so Wegener and Rasmus Villumsen took two dog sleds and made for West camp. (Georgi later found that he had underestimated the supplies, and that Wegener and Villumsen could have overwintered at Eismitte.)

They took no food for the dogs and killed them one by one to feed the rest until they could run only one sled. While Villumsen rode the sled, Wegener had to use skis, but they never reached the camp: Wegener died and Villumsen was never seen again. After Wegener was declared missing in May 1931, and his body found shortly thereafter,

On 24 September, although the route markers were by now largely buried under snow, Wegener set out with thirteen Greenlanders and his meteorologist Fritz Loewe to supply the camp by dog sled. During the journey, the temperature reached and Loewe's toes became so frostbitten they had to be amputated with a penknife without anaesthetic. Twelve of the Greenlanders returned to West camp. On 19 October the remaining three members of the expedition reached '.

Expedition member Johannes Georgi estimated that there were only enough supplies for three at ', so Wegener and Rasmus Villumsen took two dog sleds and made for West camp. (Georgi later found that he had underestimated the supplies, and that Wegener and Villumsen could have overwintered at Eismitte.)

They took no food for the dogs and killed them one by one to feed the rest until they could run only one sled. While Villumsen rode the sled, Wegener had to use skis, but they never reached the camp: Wegener died and Villumsen was never seen again. After Wegener was declared missing in May 1931, and his body found shortly thereafter,

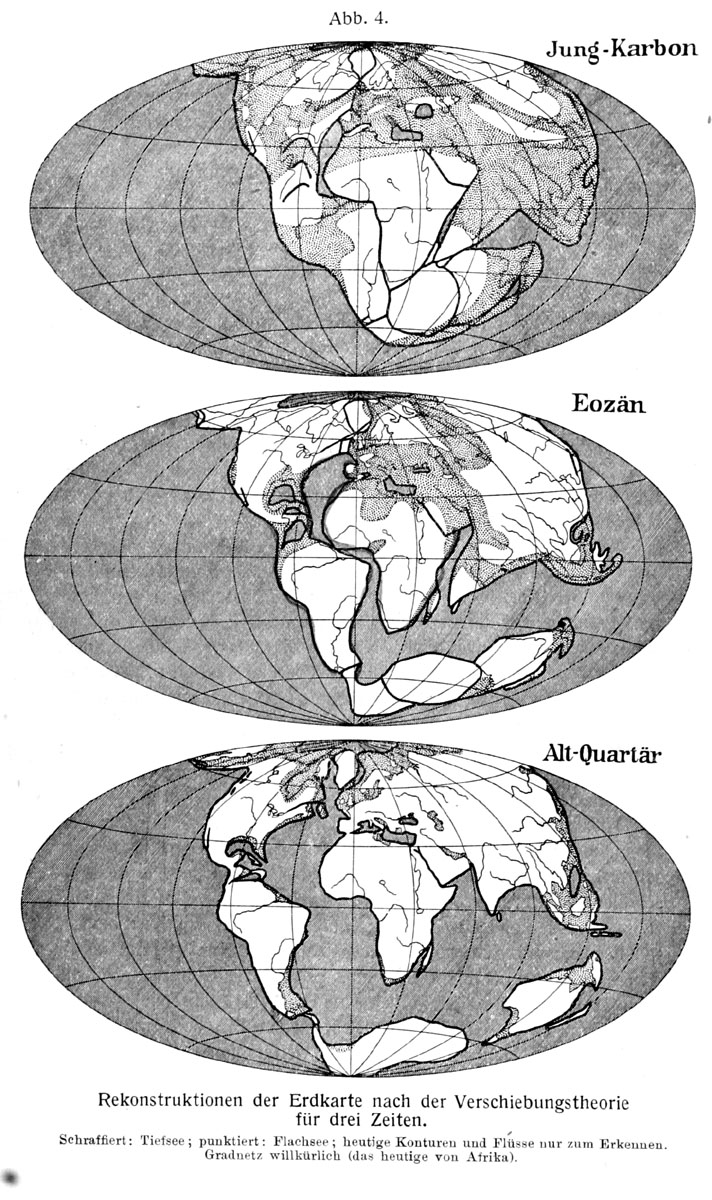

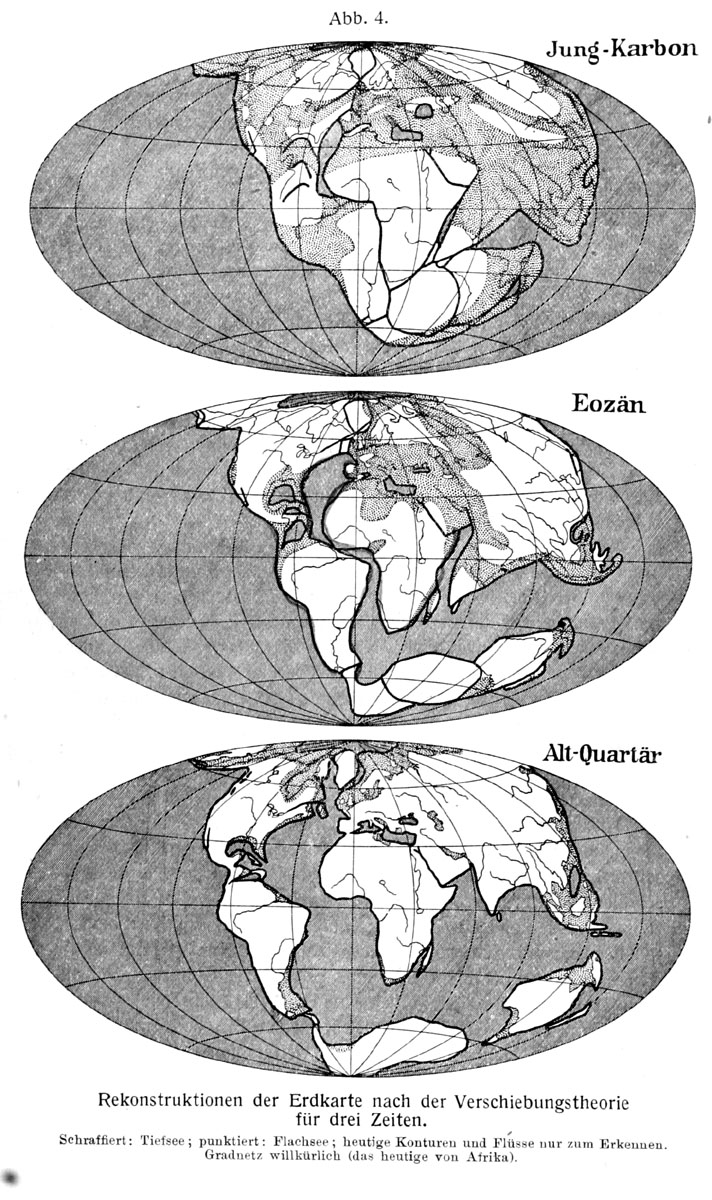

Alfred Wegener first thought of this idea by noticing that the different large landmasses of the Earth almost fit together like a jigsaw puzzle. The

Alfred Wegener first thought of this idea by noticing that the different large landmasses of the Earth almost fit together like a jigsaw puzzle. The  From 1912, Wegener publicly advocated the existence of "

From 1912, Wegener publicly advocated the existence of "

, page 259, ''

The Climates of the Geological Past

' 2015. *

Wegener Institute website

nbsp;– Biographical material * Wegener's paper (1912) online and analysed

BibNum

(for English text go to "A télécharger")

''Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane''

nbsp;– full digital facsimile at

climatologist

Climatology (from Greek , ''klima'', "place, zone"; and , ''-logia'') or climate science is the scientific study of Earth's climate, typically defined as weather conditions averaged over a period of at least 30 years. This modern field of study ...

, geologist, geophysicist

Geophysics () is a subject of natural science concerned with the physical processes and physical properties of the Earth and its surrounding space environment, and the use of quantitative methods for their analysis. The term ''geophysics'' som ...

, meteorologist

A meteorologist is a scientist who studies and works in the field of meteorology aiming to understand or predict Earth's atmospheric phenomena including the weather. Those who study meteorological phenomena are meteorologists in research, while t ...

, and polar researcher.

During his lifetime he was primarily known for his achievements in meteorology and as a pioneer of polar research, but today he is most remembered as the originator of continental drift

Continental drift is the hypothesis that the Earth's continents have moved over geologic time relative to each other, thus appearing to have "drifted" across the ocean bed. The idea of continental drift has been subsumed into the science of pla ...

hypothesis by suggesting in 1912 that the continent

A continent is any of several large landmasses. Generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, up to seven geographical regions are commonly regarded as continents. Ordered from largest in area to smallest, these seven ...

s are slowly drifting around the Earth (German: '). His hypothesis was controversial and widely rejected by mainstream geology until the 1950s, when numerous discoveries such as palaeomagnetism

Paleomagnetism (or palaeomagnetismsee ), is the study of magnetic fields recorded in rocks, sediment, or archeological materials. Geophysicists who specialize in paleomagnetism are called ''paleomagnetists.''

Certain magnetic minerals in rocks ...

provided strong support for continental drift, and thereby a substantial basis for today's model of plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large ...

. Wegener was involved in several expeditions to Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

to study polar

Polar may refer to:

Geography

Polar may refer to:

* Geographical pole, either of two fixed points on the surface of a rotating body or planet, at 90 degrees from the equator, based on the axis around which a body rotates

* Polar climate, the c ...

air circulation before the existence of the jet stream

Jet streams are fast flowing, narrow, meandering thermal wind, air currents in the Atmosphere of Earth, atmospheres of some planets, including Earth. On Earth, the main jet streams are located near the altitude of the tropopause and are west ...

was accepted. Expedition participants made many meteorological observations and were the first to overwinter on the inland Greenland ice sheet and the first to bore ice core

An ice core is a core sample that is typically removed from an ice sheet or a high mountain glacier. Since the ice forms from the incremental buildup of annual layers of snow, lower layers are older than upper ones, and an ice core contains ic ...

s on a moving Arctic glacier.

Biography

Early life and education

Alfred Wegener was born in Berlin on 1 November 1880 as the youngest of five children in a clergyman's family. His father, Richard Wegener, was a theologian and teacher of classical languages at theBerlinisches Gymnasium zum Grauen Kloster

The Evangelisches Gymnasium zum Grauen Kloster, located in suburban Schmargendorf, Berlin, is an independent school with a humanistic profile, known as one of the most prestigious schools in Germany. Founded by the Evangelical Church in West Berli ...

. In 1886 his family purchased a former manor house near Rheinsberg

Rheinsberg () is a town and a municipality in the Ostprignitz-Ruppin district, in Brandenburg, Germany. It is located on lake and the river Rhin, approximately 20 km north-east of Neuruppin and 75 km north-west of Berlin.

History

Fre ...

, which they used as a vacation home. Today there is an Alfred Wegener Memorial site and tourist information office in a nearby building that was once the local schoolhouse.

He was cousin to film pioneer Paul Wegener

Paul Wegener (11 December 1874 – 13 September 1948) was a German actor, writer, and film director known for his pioneering role in German expressionist cinema.

Acting career

At the age of 20, Wegener decided to end his law studies and conce ...

.

Wegener attended school at the ' on Wallstrasse in Berlin (a fact which is memorialised on a plaque on this protected building, now a school of music), graduating as the best in his class.

Wegener studied Physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

, meteorology and Astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

in Berlin, Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; Palatine German language, Palatine German: ''Heidlberg'') is a city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Neckar in south-west Germany. As of the 2016 census, its population was 159,914 ...

and Innsbruck

Innsbruck (; bar, Innschbruck, label=Bavarian language, Austro-Bavarian ) is the capital of Tyrol (state), Tyrol and the List of cities and towns in Austria, fifth-largest city in Austria. On the Inn (river), River Inn, at its junction with the ...

. His teachers in Berlin included Wilhelm Foerster

Wilhelm Julius Foerster (16 December 1832 – 18 January 1921) was a German astronomer. His name can also be written Förster, but is usually written "Foerster" even in most German sources where 'ö' is otherwise used in the text.

Biography

A ...

for astronomy, and Max Planck

Max Karl Ernst Ludwig Planck (, ; 23 April 1858 – 4 October 1947) was a German theoretical physicist whose discovery of energy quanta won him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1918.

Planck made many substantial contributions to theoretical p ...

for thermodynamics.

Wegener took away from Planck’s teaching a strong commitment to brevity in the service of clarity. He adopted a caution, bordering on aloofness, in offering mechanical models and causal explanations, especially of the sort that only confirmed what one knew from experience without adding anything to the facts. ..Most importantly, he heeded Planck’s injunction never to consider any form of a theory as final, and to think of “good theory” simply as that mode of treating phenomena that corresponded to the actual state of a science at that moment—and never to one's aspirations for it.From 1902 to 1903 during his studies he was an assistant at the

Urania

Urania ( ; grc, , Ouranía; modern Greek shortened name ''Ránia''; meaning "heavenly" or "of heaven") was, in Greek mythology, the muse of astronomy, and in later times, of Christian poetry. Urania is the goddess of astronomy and stars, he ...

astronomical observatory. He obtained a doctorate in astronomy in 1905 based on a dissertation written under the supervision of Julius Bauschinger

Julius Bauschinger (January 28, 1860 – January 21, 1934) was a German astronomer.

Biography

Julius Bauschinger was born in Fürth, the son of the physicist Johann Bauschinger. He studied at the Universities of Munich and Berlin, graduating un ...

at ''Friedrich Wilhelms University'' (today Humboldt University

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative of ...

), Berlin. Wegener had always maintained a strong interest in the developing fields of meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did not ...

and climatology

Climatology (from Greek , ''klima'', "place, zone"; and , '' -logia'') or climate science is the scientific study of Earth's climate, typically defined as weather conditions averaged over a period of at least 30 years. This modern field of stud ...

and his studies afterwards focused on these disciplines.

In 1905 Wegener became an assistant at the Aeronautisches Observatorium Lindenberg near Beeskow

Beeskow ( dsb, Bezkow) is a town in Brandenburg, Germany, and capital of the Oder-Spree district. It is situated on the river Spree, 30 km southwest of Frankfurt an der Oder.

Demography

File:Bevölkerungsentwicklung Beeskow.pdf, Developme ...

. He worked there with his brother Kurt, two years his senior, who was likewise a scientist with an interest in meteorology and polar research. The two pioneered the use of weather balloons to track air masses. On a balloon ascent undertaken to carry out meteorological investigations and to test a celestial navigation

Celestial navigation, also known as astronavigation, is the practice of position fixing using stars and other celestial bodies that enables a navigator to accurately determine their actual current physical position in space (or on the surface of ...

method using a particular type of quadrant (“Libellenquadrant”), the Wegener brothers set a new record for a continuous balloon flight, remaining aloft 52.5 hours from 5–7 April 1906.

First Greenland expedition and years in Marburg

In that same year 1906, Wegener participated in the first of his four Greenland expeditions, later regarding this experience as marking a decisive turning point in his life. TheDenmark expedition

The Denmark expedition ( da, Danmark-ekspeditionen), also known as the Denmark Expedition to Greenland's Northeast Coast, and as the Danmark Expedition after the ship, was an expedition to the northeast of Greenland in 1906–1908.

Despite being ...

was led by the Dane Ludvig Mylius-Erichsen

Ludvig Mylius-Erichsen (15 January 1872 – 25 November 1907) was a Danish author, ethnologist, and explorer, from Ringkøbing. He was most notably an explorer of Greenland.

Literary expedition

With Count Harald Moltke and Knud Rasmussen Mylius-E ...

and charged with studying the last unknown portion of the northeastern coast of Greenland. During the expedition Wegener constructed the first meteorological station in Greenland near Danmarkshavn

Danmarkshavn (Denmark's Harbour) is a small weather station located in Dove Bay, on the southern shore of the Germania Land Peninsula, in Northeast Greenland National Park, Greenland.

History

The location was chosen as a suitable winter harbor b ...

, where he launched kite

A kite is a tethered heavier than air flight, heavier-than-air or lighter-than-air craft with wing surfaces that react against the air to create Lift (force), lift and Drag (physics), drag forces. A kite consists of wings, tethers and anchors. ...

s and tethered balloons

A tether is a cord, fixture, or flexible attachment that characteristically anchors something movable to something fixed; it also maybe used to connect two movable objects, such as an item being towed by its tow.

Applications for tethers includ ...

to make meteorological measurements in an Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

climatic zone. Here Wegener also made his first acquaintance with death in a wilderness of ice when the expedition leader and two of his colleagues died on an exploratory trip undertaken with sled dog

A sled dog is a dog trained and used to pull a land vehicle in Dog harness, harness, most commonly a Dog sled, sled over snow.

Sled dogs have been used in the Arctic for at least 8,000 years and, along with watercraft, were the only transport ...

s.

After his return in 1908 and until World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Wegener was a lecturer in meteorology, applied astronomy and cosmic physics at the University of Marburg

The Philipps University of Marburg (german: Philipps-Universität Marburg) was founded in 1527 by Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse, which makes it one of Germany's oldest universities and the oldest still operating Protestant university in the wor ...

. His students and colleagues in Marburg particularly valued his ability to clearly and understandably explain even complex topics and current research findings without sacrificing precision. His lectures formed the basis of what was to become a standard textbook in meteorology, first written In 1909/1910: ''Thermodynamik der Atmosphäre'' (Thermodynamics of the Atmosphere), in which he incorporated many of the results of the Greenland expedition.

On 6 January 1912 he presented his first proposal of continental drift in a lecture to the Geologischen Vereinigung at the Senckenberg Museum

The Naturmuseum Senckenberg is a museum of natural history, located in Frankfurt am Main. It is the second-largest of its type in Germany. The museum contains a large and diverse collection of birds with 90,000 bird skins, 5,050 egg sets, 17,0 ...

, Frankfurt am Main

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , "Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on its na ...

. Later in 1912 he made the case for the theory in a long, three-part article and a shorter summary.

Second Greenland expedition

Plans for a new Greenland expedition grew out of Wegener andJohan Peter Koch

Johan Peter Koch (15 January 1870 – 13 January 1928) was a Danish captain and explorer of the Arctic dependencies of Denmark, born at Vestenskov. He was the uncle of the geologist Lauge Koch

Career

J.P. Koch participated in Amdrup's expeditio ...

's frustration with the disorganisation and meager scientific results of the Danmark expedition

The Denmark expedition ( da, Danmark-ekspeditionen), also known as the Denmark Expedition to Greenland's Northeast Coast, and as the Danmark Expedition after the ship, was an expedition to the northeast of Greenland in 1906–1908.

Despite being ...

. The new expedition would involve only four men, take place in 1912-1913, and have Koch for leader.

After a stopover in Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

to purchase and test ponies

A pony is a type of small horse ('' Equus ferus caballus''). Depending on the context, a pony may be a horse that is under an approximate or exact height at the withers, or a small horse with a specific conformation and temperament. Compared ...

as pack animals, the expedition arrived in Danmarkshavn. Even before the trip to the inland ice began the expedition was almost annihilated by a calving glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its Ablation#Glaciology, ablation over many years, often Century, centuries. It acquires dis ...

. Koch broke his leg when he fell into a glacier crevasse and spent months recovering in a sickbed. Wegener and Koch were the first to winter on the inland ice in northeast Greenland. Inside their hut they drilled to a depth of 25 m with an auger. In summer 1913 the team crossed the inland ice, the four expedition participants covering a distance twice as long as Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen (; 10 October 186113 May 1930) was a Norwegian polymath and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. He gained prominence at various points in his life as an explorer, scientist, diplomat, and humanitarian. He led the team t ...

's southern Greenland crossing in 1888. Only a few kilometres from the western Greenland settlement of Kangersuatsiaq

Kangersuatsiaq (old spelling: ''Kangerssuatsiaq''), formerly Prøven, is an island settlement in the Avannaata municipality in northwestern Greenland. It had 130 inhabitants in 2020.

Upernavik Archipelago

Kangersuatsiaq is located within Upe ...

the small team ran out of food while struggling to find their way through difficult glacial break-up terrain. But at the last moment, after the last pony and dog had been eaten, they were picked up at a fjord

In physical geography, a fjord or fiord () is a long, narrow inlet with steep sides or cliffs, created by a glacier. Fjords exist on the coasts of Alaska, Antarctica, British Columbia, Chile, Denmark, Germany, Greenland, the Faroe Islands, Ice ...

by the clergyman of Upernavik

Upernavik (Kalaallisut: "Springtime Place") is a small town in the Avannaata municipality in northwestern Greenland, located on a small island of the same name. With 1,092 inhabitants as of 2020, it is the twelfth-largest town in Greenland. It c ...

, who just happened to be visiting a remote congregation at the time.

Family

Later in 1913, after his return Wegener married Else Köppen, the daughter of his former teacher and mentor, the meteorologistWladimir Köppen

Wladimir Peter Köppen (; russian: Влади́мир Петро́вич Кёппен, translit=Vladimir Petrovich Kyoppen; 25 September 1846 – 22 June 1940) was a Russian-German geographer, meteorologist, climatologist and botanist. After stu ...

. The young pair lived in Marburg

Marburg ( or ) is a university town in the German federal state (''Bundesland'') of Hesse, capital of the Marburg-Biedenkopf district (''Landkreis''). The town area spreads along the valley of the river Lahn and has a population of approximate ...

, where Wegener resumed his university lectureship. There his two older daughters were born, Hilde (1914–1936) and Sophie ("Käte", 1918–2012). Their third daughter Hanna Charlotte ("Lotte", 1920–1989) was born in Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

. Lotte would in 1938 marry the famous Austrian mountaineer and adventurer Heinrich Harrer

Heinrich Harrer (; 6 July 1912 – 7 January 2006) was an Austrian mountaineer, sportsman, geographer, ''Oberscharführer'' in the ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS), and author. He was a member of the four-man climbing team that made the first ascent of th ...

, while in 1939, Käte married Siegfried Uiberreither

Siegfried Uiberreither (29 March 1908 – 29 December 1984) was an Austrian Nazi ''Gauleiter'' and ''Reichsstatthalter'' of the Reichsgau Styria during the Third Reich.

Early life

Born in Salzburg, he was the son of an engineer named Josef Ü ...

, Austrian Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

Gauleiter

A ''Gauleiter'' () was a regional leader of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) who served as the head of a ''Administrative divisions of Nazi Germany, Gau'' or ''Reichsgau''. ''Gauleiter'' was the third-highest Ranks and insignia of the Nazi Party, rank in ...

of Styria

Styria (german: Steiermark ; Serbo-Croatian and sl, ; hu, Stájerország) is a state (''Bundesland'') in the southeast of Austria. With an area of , Styria is the second largest state of Austria, after Lower Austria. Styria is bordered to ...

.

World War I

As an infantry reserve officer Wegener was immediately called up when theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

began in 1914. On the war front in Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

he experienced fierce fighting but his term lasted only a few months: after being wounded twice he was declared unfit for active service and assigned to the army weather service. This activity required him to travel constantly between various weather stations in Germany, on the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

, on the Western Front and in the Baltic region

The terms Baltic Sea Region, Baltic Rim countries (or simply the Baltic Rim), and the Baltic Sea countries/states refer to slightly different combinations of countries in the general area surrounding the Baltic Sea, mainly in Northern Europe. ...

.

Nevertheless, he was able in 1915 to complete the first version of his major work, ''Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane'' (“The Origin of Continents and Oceans”). His brother Kurt remarked that Alfred Wegener's motivation was to “reestablish the connection between geophysics

Geophysics () is a subject of natural science concerned with the physical processes and physical properties of the Earth and its surrounding space environment, and the use of quantitative methods for their analysis. The term ''geophysics'' som ...

on the one hand and geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and ...

and geology on the other, which had become completely ruptured because of the specialized development of these branches of science.”

Interest in this small publication was however low, also because of wartime chaos. By the end of the war Wegener had published almost 20 additional meteorological and geophysical papers in which he repeatedly embarked for new scientific frontiers. In 1917 he undertook a scientific investigation of the Treysa meteorite.

Postwar period

In 1919, Wegener replaced Köppen as head of the Meteorological Department at the German Naval Observatory (''Deutsche Seewarte'') and moved toHamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

with his wife and their two daughters. In 1921 he was moreover appointed senior lecturer at the new University of Hamburg

The University of Hamburg (german: link=no, Universität Hamburg, also referred to as UHH) is a public research university in Hamburg, Germany. It was founded on 28 March 1919 by combining the previous General Lecture System ('' Allgemeines Vor ...

. From 1919 to 1923 Wegener did pioneering work on reconstructing the climate of past eras (now known as "paleoclimatology

Paleoclimatology (British spelling, palaeoclimatology) is the study of climates for which direct measurements were not taken. As instrumental records only span a tiny part of Earth's history, the reconstruction of ancient climate is important to ...

"), closely in collaboration with Milutin Milanković

Milutin Milanković (sometimes anglicised as Milankovitch; sr-Cyrl, Милутин Миланковић ; 28 May 1879 – 12 December 1958) was a Serbian mathematician, astronomer, climatologist, geophysicist, civil engineer and popularizer of ...

, publishing ''Die Klimate der geologischen Vorzeit'' (“The Climates of the Geological Past”) together with his father-in-law, Wladimir Köppen, in 1924. In 1922 the third, fully revised edition of “The Origin of Continents and Oceans” appeared, and discussion began on his theory of continental drift, first in the German language area and later internationally. Withering criticism was the response of most experts.

In 1924 Wegener was appointed to a professorship in meteorology and geophysics in Graz

Graz (; sl, Gradec) is the capital city of the Austrian state of Styria and second-largest city in Austria after Vienna. As of 1 January 2021, it had a population of 331,562 (294,236 of whom had principal-residence status). In 2018, the popul ...

, a position that was both secure and free of administrative duties. He concentrated on physics and the optics of the atmosphere as well as the study of tornado

A tornado is a violently rotating column of air that is in contact with both the surface of the Earth and a cumulonimbus cloud or, in rare cases, the base of a cumulus cloud. It is often referred to as a twister, whirlwind or cyclone, altho ...

es. He had studied tornadoes for several years by this point, publishing the first thorough European tornado climatology

Tornadoes have been recorded on all continents except Antarctica. They are most common in the middle latitudes where conditions are often favorable for convective storm development. The United States has the most tornadoes of any country, as we ...

in 1917. He also posited tornado vortex structures and formative processes. Scientific assessment of his second Greenland expedition (ice measurements, atmospheric optics, etc.) continued to the end of the 1920s.

In November 1926 Wegener presented his continental drift theory at a symposium of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists

The American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG) is one of the world's largest professional geological societies with more than 40,000 members across 129 countries as of 2021. The AAPG works to "advance the science of geology, especially as ...

in New York City, again earning rejection from everyone but the chairman. Three years later the fourth and final expanded edition of “The Origin of Continents and Oceans” appeared.

Third and fourth Greenland expeditions

In April-October 1929, Wegener embarked on his third expedition to Greenland, which laid the groundwork for the main expedition which he was planning to lead in 1930-1931.

Wegener's last Greenland expedition was in 1930. The 14 participants under his leadership were to establish three permanent stations from which the thickness of the Greenland ice sheet could be measured and year-round Arctic weather observations made.

They would travel on the ice cap using two innovative, propeller-driven

In April-October 1929, Wegener embarked on his third expedition to Greenland, which laid the groundwork for the main expedition which he was planning to lead in 1930-1931.

Wegener's last Greenland expedition was in 1930. The 14 participants under his leadership were to establish three permanent stations from which the thickness of the Greenland ice sheet could be measured and year-round Arctic weather observations made.

They would travel on the ice cap using two innovative, propeller-driven snowmobile

A snowmobile, also known as a Ski-Doo, snowmachine, sled, motor sled, motor sledge, skimobile, or snow scooter, is a motorized vehicle designed for winter travel and recreation on snow. It is designed to be operated on snow and ice and does not ...

s, in addition to ponies and dog sleds.

Wegener felt personally responsible for the expedition's success, as the German government

The Federal Cabinet or Federal Government (german: link=no, Bundeskabinett or ') is the chief executive body of the Federal Republic of Germany. It consists of the Federal Chancellor and cabinet ministers. The fundamentals of the cabinet's or ...

had contributed $120,000 ($1.5 million in 2007 dollars). Success depended on enough provisions being transferred from West camp to ' ("mid-ice") for two men to winter there, and this was a factor in the decision that led to his death. Owing to a late thaw, the expedition was six weeks behind schedule and, as summer ended, the men at ' sent a message that they had insufficient fuel and so would return on 20 October.

On 24 September, although the route markers were by now largely buried under snow, Wegener set out with thirteen Greenlanders and his meteorologist Fritz Loewe to supply the camp by dog sled. During the journey, the temperature reached and Loewe's toes became so frostbitten they had to be amputated with a penknife without anaesthetic. Twelve of the Greenlanders returned to West camp. On 19 October the remaining three members of the expedition reached '.

Expedition member Johannes Georgi estimated that there were only enough supplies for three at ', so Wegener and Rasmus Villumsen took two dog sleds and made for West camp. (Georgi later found that he had underestimated the supplies, and that Wegener and Villumsen could have overwintered at Eismitte.)

They took no food for the dogs and killed them one by one to feed the rest until they could run only one sled. While Villumsen rode the sled, Wegener had to use skis, but they never reached the camp: Wegener died and Villumsen was never seen again. After Wegener was declared missing in May 1931, and his body found shortly thereafter,

On 24 September, although the route markers were by now largely buried under snow, Wegener set out with thirteen Greenlanders and his meteorologist Fritz Loewe to supply the camp by dog sled. During the journey, the temperature reached and Loewe's toes became so frostbitten they had to be amputated with a penknife without anaesthetic. Twelve of the Greenlanders returned to West camp. On 19 October the remaining three members of the expedition reached '.

Expedition member Johannes Georgi estimated that there were only enough supplies for three at ', so Wegener and Rasmus Villumsen took two dog sleds and made for West camp. (Georgi later found that he had underestimated the supplies, and that Wegener and Villumsen could have overwintered at Eismitte.)

They took no food for the dogs and killed them one by one to feed the rest until they could run only one sled. While Villumsen rode the sled, Wegener had to use skis, but they never reached the camp: Wegener died and Villumsen was never seen again. After Wegener was declared missing in May 1931, and his body found shortly thereafter, Kurt Wegener

Kurt Wegener (April 3, 1878 in Berlin - February 29, 1964 in Munich) was a German polar explorer and meteorologist.

He was the brother of Alfred Wegener. He worked at the Meteorological Observatory Lindenberg near Beeskow

Beeskow ( dsb, Bezkow) ...

took over the expedition's leadership in July, according to the prearranged plan for such an eventuality.

This expedition inspired the Greenland expedition episode of Adam Melfort in John Buchan

John Buchan, 1st Baron Tweedsmuir (; 26 August 1875 – 11 February 1940) was a Scottish novelist, historian, and Unionist politician who served as Governor General of Canada, the 15th since Canadian Confederation.

After a brief legal career ...

's 1933 novel '' A Prince of the Captivity''.

Death

Wegener died in Greenland in November 1930 while returning from an expedition to bring food to a group of researchers camped in the middle of an icecap. He supplied the camp successfully, but there was not enough food at the camp for him to stay there. He and a colleague, Rasmus Villumsen, took dog sleds to travel to another camp – which they never reached. Villumsen buried Wegener's body with great care, a pair of skis marking the grave site. After burying Wegener, Villumsen resumed his journey to West camp, but he was never seen again. Six months later, on 12 May 1931, the grave was discovered halfway between ' and West camp. Expedition members built a pyramid-shapedmausoleum

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the interment space or burial chamber of a deceased person or people. A mausoleum without the person's remains is called a cenotaph. A mausoleum may be consid ...

in the ice and snow, and Alfred Wegener's body was laid to rest in it. Wegener had been 50 years of age and a heavy smoker, and it was believed that he had died of heart failure brought on by overexertion

Exertion is the physical or perceived use of energy.Newton's Third Law, Elert, Glenn. “Forces.” ''Viscosity – The Physics Hypertextbook'', physics.info/newton-first/. Exertion traditionally connotes a strenuous or costly ''effort'', resulting ...

. Villumsen was 23 when he died, and it is estimated that his body, and Wegener's diary, now lie under more than of accumulated ice and snow.

Continental drift theory

Alfred Wegener first thought of this idea by noticing that the different large landmasses of the Earth almost fit together like a jigsaw puzzle. The

Alfred Wegener first thought of this idea by noticing that the different large landmasses of the Earth almost fit together like a jigsaw puzzle. The continental shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island ...

of the Americas fits closely to Africa and Europe. Antarctica, Australia, India and Madagascar fit next to the tip of Southern Africa. But Wegener only published his idea after reading a paper in 1911 which criticised the prevalent hypothesis, that a bridge of land once connected Europe and America, on the grounds that this contradicts isostasy

Isostasy (Greek ''ísos'' "equal", ''stásis'' "standstill") or isostatic equilibrium is the state of gravitational equilibrium between Earth's crust (or lithosphere) and mantle such that the crust "floats" at an elevation that depends on its ...

. Wegener's main interest was meteorology, and he wanted to join the Denmark-Greenland expedition scheduled for mid-1912. He presented his Continental Drift hypothesis on 6 January 1912. He analysed both sides of the Atlantic Ocean for rock type, geological structures and fossils. He noticed that there was a significant similarity between matching sides of the continents, especially in fossil plants

Paleobotany, which is also spelled as palaeobotany, is the branch of botany dealing with the recovery and identification of plant remains from geological contexts, and their use for the biological reconstruction of past environments (paleogeogr ...

.

continental drift

Continental drift is the hypothesis that the Earth's continents have moved over geologic time relative to each other, thus appearing to have "drifted" across the ocean bed. The idea of continental drift has been subsumed into the science of pla ...

", arguing that all the continents were once joined together in a single landmass and had since drifted apart. He supposed that the mechanisms causing the drift might be the centrifugal force of the Earth's rotation ("") or the astronomical precession

Precession is a change in the orientation of the rotational axis of a rotating body. In an appropriate reference frame it can be defined as a change in the first Euler angle, whereas the third Euler angle defines the rotation itself. In othe ...

. Wegener also speculated about sea-floor spreading

Seafloor spreading or Seafloor spread is a process that occurs at mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust is formed through volcanic activity and then gradually moves away from the ridge.

History of study

Earlier theories by Alfred Wegener an ...

and the role of the mid-ocean ridge

A mid-ocean ridge (MOR) is a seafloor mountain system formed by plate tectonics. It typically has a depth of about and rises about above the deepest portion of an ocean basin. This feature is where seafloor spreading takes place along a diverge ...

s, stating that "the Mid-Atlantic Ridge ... zone in which the floor of the Atlantic, as it keeps spreading, is continuously tearing open and making space for fresh, relatively fluid and hot sima

Sima or SIMA may refer to:

People

* Sima (Chinese surname)

* Sima (given name), a Persian feminine name in use in Iran and Turkey

* Sima (surname)

Places

* Sima, Comoros, on the island of Anjouan, near Madagascar

* Sima de los Huesos, a c ...

ising Ising is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Ernst Ising (1900–1998), German physicist

* Gustav Ising (1883–1960), Swedish accelerator physicist

* Rudolf Ising, animator for ''MGM'', together with Hugh Harman often credited ...

from depth." However, he did not pursue these ideas in his later works.

In 1915, in the first edition of his book, ', written in German,

Wegener drew together evidence from various fields to advance the theory that there had once been a giant continent, which he named "'"

(German for "primal continent", analogous to the Greek "Pangaea

Pangaea or Pangea () was a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras. It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous approximately 335 million y ...

",

meaning "All-Lands" or "All-Earth"). Expanded editions during the 1920s presented further evidence. (The first English edition was published in 1924 as ''The Origin of Continents and Oceans'', a translation of the 1922 third German edition.) The last German edition, published in 1929, revealed the significant observation that shallower oceans were geologically younger. It was, however, not translated into English until 1962.

Reaction

In his work, Wegener presented a large amount of observational evidence in support of continental drift, but the mechanism remained a problem, partly because Wegener's estimate of the velocity of continental motion, 250 cm/year, was too high. (The currently accepted rate for the separation of the Americas from Europe and Africa is about 2.5 cm/year.) While his ideas attracted a few early supporters such asAlexander Du Toit

Alexander Logie du Toit FRS ( ; 14 March 1878 – 25 February 1948) was a geologist from South Africa and an early supporter of Alfred Wegener's theory of continental drift.

Early life and education

Du Toit was born in Newlands, Cape Town in ...

from South Africa, Arthur Holmes

Arthur Holmes (14 January 1890 – 20 September 1965) was an English geologist who made two major contributions to the understanding of geology. He pioneered the use of radiometric dating of minerals, and was the first earth scientist to grasp ...

in England and Milutin Milanković

Milutin Milanković (sometimes anglicised as Milankovitch; sr-Cyrl, Милутин Миланковић ; 28 May 1879 – 12 December 1958) was a Serbian mathematician, astronomer, climatologist, geophysicist, civil engineer and popularizer of ...

in Serbia, for whom continental drift

Continental drift is the hypothesis that the Earth's continents have moved over geologic time relative to each other, thus appearing to have "drifted" across the ocean bed. The idea of continental drift has been subsumed into the science of pla ...

theory was the premise for investigating polar wandering,

the hypothesis was initially met with scepticism from geologists, who viewed Wegener as an outsider and were resistant to change. Nevertheless, the eminent Swiss geologist Émile Argand

Émile Argand (6 January 1879 – 14 September 1940) was a Swiss geologist.

He was born in Eaux-Vives near Geneva. He attended vocational school in Geneva then worked as a draftsman. He studied anatomy in Paris, but gave up medicine to pursue his ...

advocated Wegener's theory in his inaugural address to the 1922 International Geological Congress.

The one American edition of Wegener's work, published in 1925, was written in "a dogmatic style that often results from German translations". In 1926, at the initiative of Willem van der Gracht, the American Association of Petroleum Geologists

The American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG) is one of the world's largest professional geological societies with more than 40,000 members across 129 countries as of 2021. The AAPG works to "advance the science of geology, especially as ...

organised a symposium on the continental drift hypothesis. The opponents argued, as did the Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as wel ...

er geologist Franz Kossmat

Franz Kossmat ( 22 August 1871 in Vienna – 1 December 1938 in Leipzig) was an Austrian-German geologist, for twenty years the director of the Geological Survey of Saxony under both the kingdom and the subsequent German Republic.

Kossmat was ...

, that the oceanic crust was too firm for the continents to "simply plough through".

From at least 1910, Wegener imagined the continents once fitting together not at the current shore line, but 200 m below this, at the level of the continental shelves

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island ...

, where they match well. Part of the reason Wegener's ideas were not initially accepted was the misapprehension that he was suggesting the continents had fit along the current coastline. Charles Schuchert

Charles Schuchert (July 3, 1858 – November 20, 1942) was an American invertebrate paleontologist who was a leader in the development of paleogeography, the study of the distribution of lands and seas in the geological past.

Biography

He was bo ...

commented:

Wegener was in the audience for this lecture, but made no attempt to defend his work, possibly because of an inadequate command of the English language.

In 1943, George Gaylord Simpson

George Gaylord Simpson (June 16, 1902 – October 6, 1984) was an American paleontologist. Simpson was perhaps the most influential paleontologist of the twentieth century, and a major participant in the Modern synthesis (20th century), modern ...

wrote a strong critique of the theory (as well as the rival theory of sunken land bridges) and gave evidence for the idea that similarities of flora

Flora is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous) native plants. Sometimes bacteria and fungi are also referred to as flora, as in the terms '' gut flora'' or '' skin flora''.

E ...

and fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is ''flora'', and for fungi, it is '' funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as '' biota''. Zoo ...

between the continents could best be explained by these being fixed land masses which over time were connected and disconnected by periodic flooding, a theory known as permanentism. Alexander du Toit wrote a rejoinder to this the following year.

Alfred Wegener has been mischaracterised as a lone genius whose theory of continental drift met widespread rejection until well after his death. In fact, the main tenets of the theory gained widespread acceptance by European researchers already in the 1920s, and the debates were mostly about specific details. However, the theory took longer to be accepted in North America.

Modern developments

In the early 1950s, the new science ofpaleomagnetism

Paleomagnetism (or palaeomagnetismsee ), is the study of magnetic fields recorded in rocks, sediment, or archeological materials. Geophysicists who specialize in paleomagnetism are called ''paleomagnetists.''

Certain magnetic minerals in rock ...

pioneered at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

by S. K. Runcorn and at Imperial College

Imperial College London (legally Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine) is a public research university in London, United Kingdom. Its history began with Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria, who developed his vision for a cu ...

by P.M.S. Blackett

Patrick Maynard Stuart Blackett, Baron Blackett (18 November 1897 – 13 July 1974) was a British experimental physics, experimental physicist known for his work on cloud chambers, cosmic rays, and paleomagnetism, winning the Nobel Priz ...

was soon producing data in favour of Wegener's theory. By early 1953 samples taken from India showed that the country had previously been in the Southern hemisphere as predicted by Wegener. By 1959, the theory had enough supporting data that minds were starting to change, particularly in the United Kingdom where, in 1964, the Royal Society held a symposium on the subject.

The 1960s saw several relevant developments in geology, notably the discoveries of seafloor spreading

Seafloor spreading or Seafloor spread is a process that occurs at mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust is formed through volcanic activity and then gradually moves away from the ridge.

History of study

Earlier theories by Alfred Wegener an ...

and Wadati–Benioff zone

A Wadati–Benioff zone (also Benioff–Wadati zone or Benioff zone or Benioff seismic zone) is a planar zone of seismicity corresponding with the down-going slab in a subduction zone. Differential motion along the zone produces numerous earthqu ...

s, and this led to the rapid resurrection of the continental drift hypothesis in the form of its direct descendant, the theory of plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large ...

. Maps of the geomorphology

Geomorphology (from Ancient Greek: , ', "earth"; , ', "form"; and , ', "study") is the scientific study of the origin and evolution of topographic and bathymetric features created by physical, chemical or biological processes operating at or n ...

of the ocean floors created by Marie Tharp

Marie Tharp (July 30, 1920 – August 23, 2006) was an American geologist and oceanographic cartographer. In the 1950s, she collaborated with geologist Bruce Heezen to produce the first scientific map of the Atlantic Ocean floor. Her cartograp ...

in cooperation with Bruce Heezen

Bruce Charles Heezen (; April 11, 1924 – June 21, 1977) was an American geologist. He worked with oceanographic cartographer Marie Tharp at Columbia University to map the Mid-Atlantic Ridge in the 1950s.

Biography

Heezen was born in Vinton, Io ...

were an important contribution to the paradigm shift

A paradigm shift, a concept brought into the common lexicon by the American physicist and philosopher Thomas Kuhn, is a fundamental change in the basic concepts and experimental practices of a scientific discipline. Even though Kuhn restricted t ...

that was starting. Wegener was then recognised as the founding father of one of the major scientific revolutions of the 20th century.

With the advent of the Global Positioning System

The Global Positioning System (GPS), originally Navstar GPS, is a satellite-based radionavigation system owned by the United States government and operated by the United States Space Force. It is one of the global navigation satellite sy ...

(GPS) in 1993, it became possible to measure continental drift directly.

Awards and honours

TheAlfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research

The Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (German: ''Alfred-Wegener-Institut, Helmholtz-Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung'') is located in Bremerhaven, Germany, and a member of the Helmholtz Association o ...

in Bremerhaven

Bremerhaven (, , Low German: ''Bremerhoben'') is a city at the seaport of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen, a state of the Federal Republic of Germany.

It forms a semi-enclave in the state of Lower Saxony and is located at the mouth of the Riv ...

, Germany, was established in 1980 on Wegener's centenary. It awards the Wegener Medal in his name."2005 Annual report", page 259, ''

Alfred Wegener Institute

The Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (German: ''Alfred-Wegener-Institut, Helmholtz-Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung'') is located in Bremerhaven, Germany, and a member of the Helmholtz Association o ...

'' The crater Wegener on the Moon and the crater Wegener on Mars, as well as the asteroid

An asteroid is a minor planet of the inner Solar System. Sizes and shapes of asteroids vary significantly, ranging from 1-meter rocks to a dwarf planet almost 1000 km in diameter; they are rocky, metallic or icy bodies with no atmosphere.

...

29227 Wegener

9 (nine) is the natural number following and preceding .

Evolution of the Arabic digit

In the beginning, various Indians wrote a digit 9 similar in shape to the modern closing question mark without the bottom dot. The Kshatrapa, Andhra and ...

and the peninsula where he died in Greenland (Wegener Peninsula near Ummannaq, ), are named after him.

The European Geosciences Union

The European Geosciences Union (EGU) is a non-profit international union in the fields of Earth, planetary, and space sciences whose vision is to "realise a sustainable and just future for humanity and for the planet." The organisation has headq ...

sponsors an Alfred Wegener Medal & Honorary Membership "for scientists who have achieved exceptional international standing in atmospheric, hydrological or ocean sciences, defined in their widest senses, for their merit and their scientific achievements."

Selected works

* * * * * ** English language edition: ; British edition: Methuen, London (1968). * Köppen, W. & Wegener, A. (1924): ''Die Klimate der geologischen Vorzeit'', Borntraeger Science Publishers. English language edition:The Climates of the Geological Past

' 2015. *

See also

*Hair ice

Hair ice, also known as ice wool or frost beard, is a type of ice that forms on dead wood and takes the shape of fine, silky hair. It is somewhat uncommon, and has been reported mostly at latitudes between 45 and 55 °N in broadleaf forest ...

– Wegener introduced a theory on the growth of hair ice in 1918.

References

External links

* * *Wegener Institute website

nbsp;– Biographical material * Wegener's paper (1912) online and analysed

BibNum

(for English text go to "A télécharger")

''Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane''

nbsp;– full digital facsimile at

Linda Hall Library

The Linda Hall Library is a privately endowed American library of science, engineering and technology located in Kansas City, Missouri, sitting "majestically on a urban arboretum." It is the "largest independently funded public library of scien ...

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wegener, Alfred

1880 births

1930 deaths

20th-century German geologists

20th-century German male writers

German climatologists

German geophysicists

German meteorologists

German Army personnel of World War I

Humboldt University of Berlin alumni

Köllnisches Gymnasium alumni

Scientists from Berlin

Tectonicists

University of Marburg faculty

University of Hamburg faculty