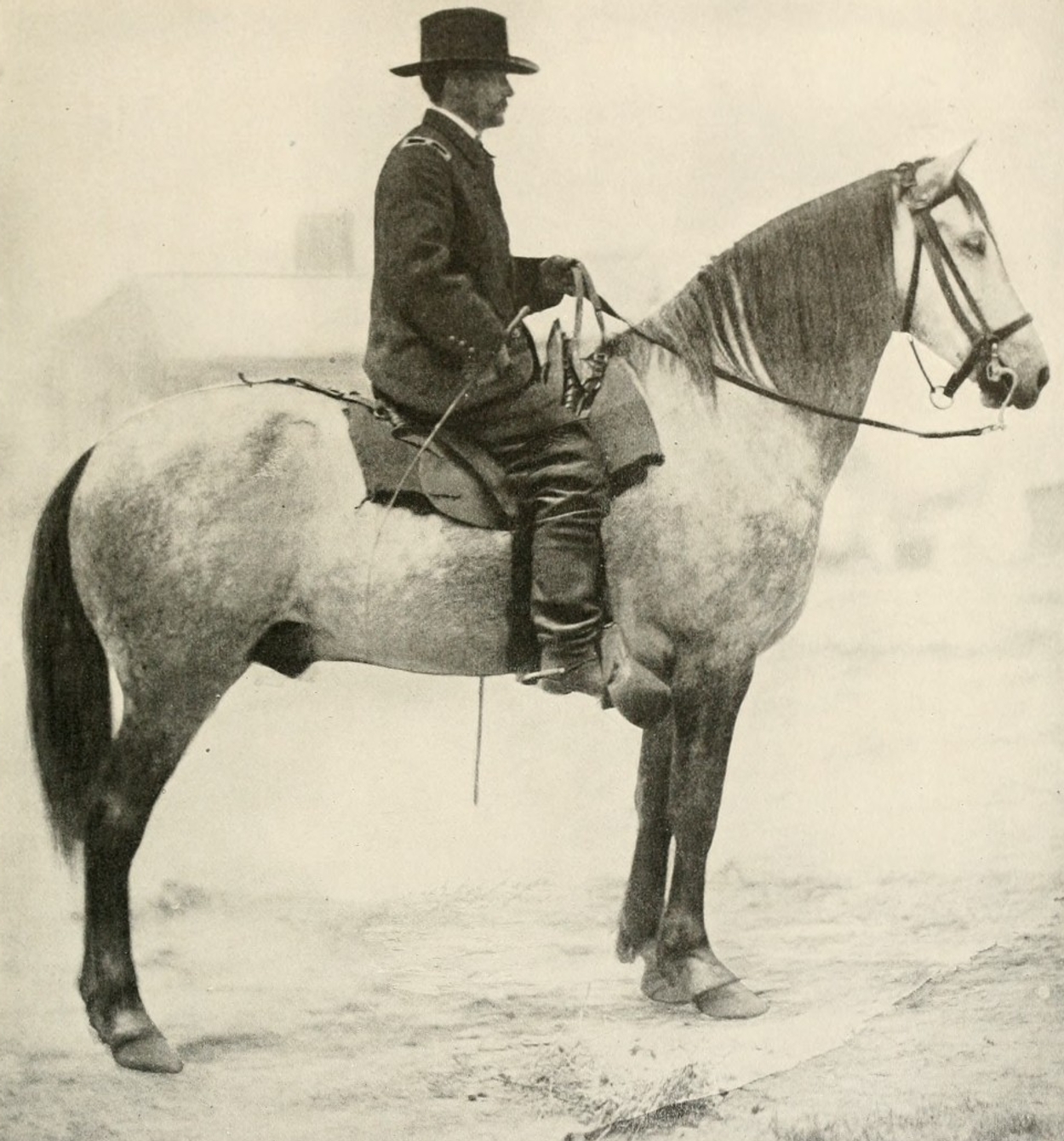

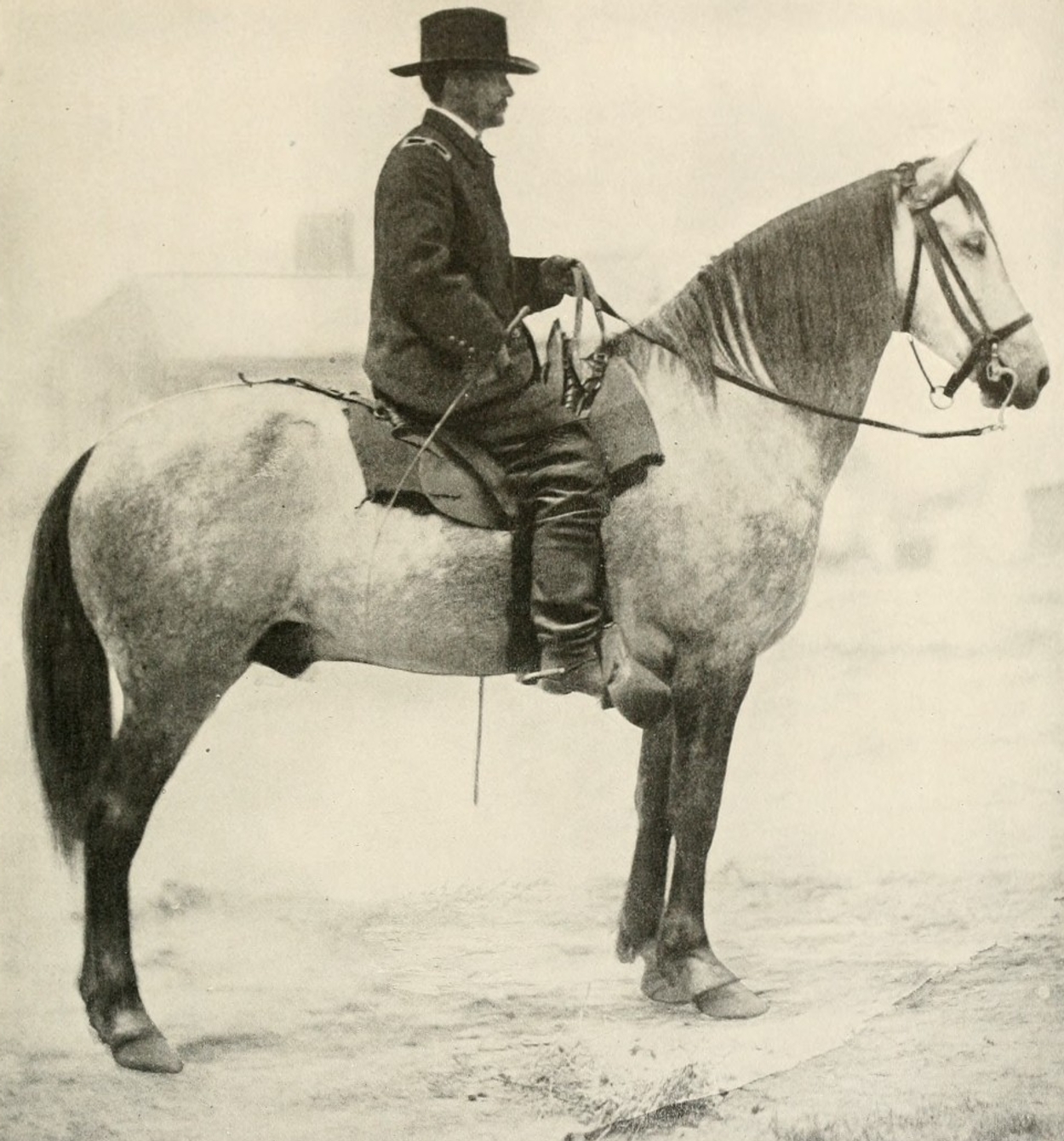

Alfred Pleasonton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alfred Pleasonton (June 7, 1824 – February 17, 1897) was a United States Army officer and

On September 2, 1862, Pleasonton assumed division command in the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac. As McClellan's chief cavalryman, it was part of Pleasonton's duties to provide his commanding general with intelligence, especially the size of enemy formation. In general, McClellan relied on the erroneous information provided to him by private detective

On September 2, 1862, Pleasonton assumed division command in the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac. As McClellan's chief cavalryman, it was part of Pleasonton's duties to provide his commanding general with intelligence, especially the size of enemy formation. In general, McClellan relied on the erroneous information provided to him by private detective

Pleasonton was transferred to the Trans-Mississippi Theater and commanded the District of Central Missouri and the District of

Pleasonton was transferred to the Trans-Mississippi Theater and commanded the District of Central Missouri and the District of

After the war, although Pleasonton had achieved the honorary rank of brevet major general in the regular army, he was mustered out of the volunteer service with the permanent rank of major of cavalry. Because he did not want to leave the cavalry, Pleasonton turned down a lieutenant colonel in the infantry, and soon became dissatisfied with his command relationship to officers he once outranked. Pleasonton resigned his commission in 1868, and was placed on the Army's retired list as a major in 1888. As a civilian, he worked as United States Collector of Internal Revenue and as

After the war, although Pleasonton had achieved the honorary rank of brevet major general in the regular army, he was mustered out of the volunteer service with the permanent rank of major of cavalry. Because he did not want to leave the cavalry, Pleasonton turned down a lieutenant colonel in the infantry, and soon became dissatisfied with his command relationship to officers he once outranked. Pleasonton resigned his commission in 1868, and was placed on the Army's retired list as a major in 1888. As a civilian, he worked as United States Collector of Internal Revenue and as ''Gettysburg Daily'' article on Pennsylvania Monument

/ref>

''America's Lighthouses''

Courier Corp., 2012. (New York: Dover Maritime, 1988) . pp. 26–35. Retrieved May 18, 2015. * Longacre, Edward G. ''The Cavalry at Gettysburg: A Tactical Study of Mounted Operations during the Civil War's Pivotal Campaign, 9 June–14 July 1863''. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986. . * Longacre, Edward G. ''Lincoln's Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of the Potomac''. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000. . * Styple, William B. ''Generals in Bronze: Interviewing the Commanders of the Civil War''. Kearny, NJ: Belle Grove Publishing, 2005. . * Taaffe, Stephen R. ''Commanding the Army of the Potomac''. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 2006. .

major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

of volunteers in the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. He commanded the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confedera ...

during the Gettysburg campaign, including the largest predominantly cavalry battle of the war, Brandy Station. In 1864, he was transferred to the Trans-Mississippi theater, where he defeated Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

General Sterling Price

Major-General Sterling "Old Pap" Price (September 14, 1809 – September 29, 1867) was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army who commanded infantry in the Western and Trans-Mississippi theaters of the American Civil War. Prior to ...

in two key battles, including the Battle of Mine Creek

The Battle of Mine Creek, also known as the Battle of the Osage, was fought on October 25, 1864, in Linn County, Kansas, as part of Price's Missouri Expedition during the American Civil War. Major General Sterling Price of the Confederate Stat ...

, the second largest cavalry battle of the war, effectively ending the war in Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

. He was the son of Stephen Pleasonton and younger brother of Augustus Pleasonton

Augustus James Pleasonton, often called A. J. Pleasonton (January 21, 1808 – July 26, 1894), was a militia general during the American Civil War. He wrote the book ''The Influence of the Blue Ray of the Sunlight and of the Blue Color of the Sky' ...

.

Early life

Pleasonton was born in Washington, D.C., on June 7, 1824.Eicher, John H., andDavid J. Eicher

David John Eicher (born August 7, 1961) is an American editor, writer, and popularizer of astronomy and space. He has been editor-in-chief of ''Astronomy'' magazine since 2002. He is author, coauthor, or editor of 23 books on science and American ...

, ''Civil War High Commands''. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. . p. 431. He was the son of Stephen

Stephen or Steven is a common English first name. It is particularly significant to Christians, as it belonged to Saint Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ), an early disciple and deacon who, according to the Book of Acts, was stoned to death; ...

and Mary Hopkins Pleasonton. Stephen was well known at the time of Alfred's birth. During the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

, as a U.S. State Department employee, he saved crucial documents in the National Archives from destruction by the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

invaders of Washington, including the original Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the ...

and the U.S. Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

. As Fifth Auditor of the U.S. Treasury, Stephen Pleasonton was the de facto superintendent of lighthouses of the United States from 1820 to 1852. His conservative approach and emphasis on the economy held back advancements in lighthouse construction and technology and led to the deterioration of some lighthouses. Since he had no technical knowledge of the field, he delegated many responsibilities to local customs inspectors. In 1852, the U.S. Congress decided reform was needed and established the Lighthouse Board to take over fiscal and administrative duties for U.S. lighthouses.

Alfred's much older brother, Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

, attended the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

and served as Assistant Adjutant General and paymaster of the state of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

; his career direction obviously affected his younger brother's and both boys were assured nomination to the Academy by their father's fame from the War of 1812. Alfred graduated from West Point on July 1, 1844, and was commissioned a brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

in the 1st U.S. Dragoons (heavy cavalry). He was stationed first at Fort Atkinson, Iowa

Fort Atkinson is a city in Winneshiek County, Iowa, United States. The population was 312 at the time of the 2020 census. It is home to the historic Fort Atkinson State Preserve and hosts a large annual fur-trapper rendezvous each September. F ...

. He followed his unit for frontier duty in Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over to ...

, Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to the ...

, and Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

. He was promoted to second lieutenant with the 2nd U.S. Dragoons on November 3, 1845. With the 2nd Dragoons, he fought in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

and received a brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

promotion to first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a s ...

for gallantry in the Battle of Palo Alto

The Battle of Palo Alto ( es, Batalla de Palo Alto) was the first major battle of the Mexican–American War and was fought on May 8, 1846, on disputed ground five miles (8 km) from the modern-day city of Brownsville, Texas. A force of so ...

and the Battle of Resaca de la Palma

The Battle of Resaca de la Palma was one of the early engagements of the Mexican–American War, where the United States Army under General Zachary Taylor engaged the retreating forces of the Mexican ''Ejército del Norte'' ("Army of the North ...

, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

, in 1846.Taaffe, Stephen R. ''Commanding the Army of the Potomac''. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 2006. . p. 100. He was promoted to first lieutenant on September 30, 1849. He served as regimental adjutant from July 1, 1854, to March 3, 1855. Pleasonton was promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

on March 3, 1855.

Civil War

Peninsula to Chancellorsville

At the start of the Civil War in 1861, Captain Pleasonton traveled with the 2nd Dragoons from Fort Crittenden,Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th state. ...

, to Washington D.C. Despite active politicking on his part, attempting to capitalize on the faded political connections of his father (who had died in 1855), Pleasonton did not earn the rapid promotions of some of his colleagues. He was transferred to the 2nd U.S. Cavalry Regiment on August 3, 1861. He was promoted to major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

on February 15, 1862. He fought without incident or prominence in the Peninsula campaign, providing Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confedera ...

commander Major General George McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

with little accurate or valuable information. On May 1, 1862, Pleasonton was nominated by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

for promotion to the grade of brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

of volunteers to rank from July 16, 1862, and the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

confirmed the appointment on July 16, 1862. President Lincoln formally appointed Pleasonton to the grade on July 18, 1862. He then commanded a brigade of cavalry in the Army of the Potomac.

On September 2, 1862, Pleasonton assumed division command in the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac. As McClellan's chief cavalryman, it was part of Pleasonton's duties to provide his commanding general with intelligence, especially the size of enemy formation. In general, McClellan relied on the erroneous information provided to him by private detective

On September 2, 1862, Pleasonton assumed division command in the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac. As McClellan's chief cavalryman, it was part of Pleasonton's duties to provide his commanding general with intelligence, especially the size of enemy formation. In general, McClellan relied on the erroneous information provided to him by private detective Allan Pinkerton

Allan J. Pinkerton (August 25, 1819 – July 1, 1884) was a Scottish cooper, abolitionist, detective, and spy, best known for creating the Pinkerton National Detective Agency in the United States and his claim to have foiled a plot in 1861 to a ...

, which resulted in McClellan's ''idee fixe'' that he was constantly unnumbered by the Confederate forces he faced. During the Maryland campaign of 1862, Pinkerton had no agents in place, so the task of estimating enemy strength fell to Pleasonton, who turned out to be as inept at it as Pinkerton. As a result, McClellan remained convinced that Confederate General Robert E. Lee's forces outnumbered his two-to-one, when the truth was almost exactly the opposite.

He was wounded in the right ear by the concussion of an artillery shell at the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

on September 17. Ever ambitious, Pleasonton was displeased that he was not promoted to major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

of volunteers for his actions, claiming erroneously that his division, and particularly the horse artillery assigned to him, had had a decisive effect on the battle. He did receive a brevet promotion to lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

in the regular army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregulars, irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenary, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the ...

, probably based solely on the inflated claims of his battle report, which were not substantiated by the reports of other generals.

At the Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the American Civil War (1861–1865), and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville campaign.

Chancellorsville is known as Lee's "perfect battle" because h ...

, Pleasonton continued his practice of self-promotion. He claimed that he temporarily halted an attack by Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, considered one of the best-known Confederate commanders, after Robert E. Lee. He played a prominent role in nearl ...

's Corps and that he was able to prevent the total destruction of the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

XI Corps 11 Corps, 11th Corps, Eleventh Corps, or XI Corps may refer to:

* 11th Army Corps (France)

* XI Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* XI Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Army

* ...

on May 2, 1863. He was persuasive enough that the commander of the Army of the Potomac, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

, told President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

that Pleasonton "saved the Union Army" at Chancellorsville. Battle reports, however, indicate that Pleasonton's role was considerably less important than he claimed, involving only a small detachment of Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

infantry on Hazel Grove. Nevertheless, his claims earned him an appointment to the grade of major general of volunteers on and to rank from June 22, 1863, and when the inept Cavalry Corps commander, Maj. Gen. George Stoneman

George Stoneman Jr. (August 8, 1822 – September 5, 1894) was a United States Army cavalry officer and politician who served as the fifteenth Governor of California from 1883 to 1887. He was trained at West Point, where his roommate was Stonewall ...

, was relieved after Chancellorsville, Hooker named Pleasonton as his temporary replacement. Pleasonton could not accept even this elevated role gracefully. He wrote to Gen. Hooker "I cannot ... remain silent as to the unsatisfactory condition in which I find this corps ... the responsibility of its present state ... does not belong to me."

Gettysburg

Pleasonton's first combat in his new role was a month later in the Gettysburg campaign. He led Union cavalry forces in theBattle of Brandy Station

The Battle of Brandy Station, also called the Battle of Fleetwood Hill, was the largest predominantly cavalry engagement of the American Civil War, as well as the largest ever to take place on American soil. It was fought on June 9, 1863, aroun ...

, the largest predominantly cavalry battle of the war. The Union cavalry essentially stumbled into J. E. B. Stuart's Confederate cavalry and the 14-hour battle was bloody but inconclusive, although Stuart was embarrassed that he had been surprised and the Union horsemen had a newfound confidence in their abilities. Subordinate officers criticized Pleasonton for not aggressively defeating Stuart at Brandy Station. Gen. Hooker had ordered Pleasonton to "disperse and destroy" the Confederate cavalry near Culpeper, Virginia

Culpeper (formerly Culpeper Courthouse, earlier Fairfax) is an incorporated town in Culpeper County, Virginia, United States. The population was 20,062 at the 2020 census, up from 16,379 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Culpeper Coun ...

, but Pleasonton claimed that he had only been ordered to make a "reconnaissance in force toward Culpeper", thus rationalizing his actions.

In the remainder of the Gettysburg Campaign up to the climactic battle, Pleasonton did not perform as a competent cavalry commander and was generally unable to inform his commander where the enemy troops were located and what their intentions were. The Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

, under Gen. Robert E. Lee, was able to slip past Union forces through the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge- ...

and north into Pennsylvania. During this period, he attempted to exercise political influence by promoting the nephew of a U.S. Congressman

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

, Captain Elon J. Farnsworth

Elon John Farnsworth (July 30, 1837 – July 3, 1863) was a Union Army captain in the American Civil War. He commanded Brigade 1, Division 3 of the Cavalry Corps (Union Army) from June 28, 1863 to July 3, 1863, when he was mortally wounded and die ...

, a member of his staff, directly to brigadier general. Pleasonton also promoted Captain Wesley Merritt

Wesley Merritt (June 16, 1836December 3, 1910) was an American major general who served in the cavalry of the United States Army during the American Civil War, American Indian Wars, and Spanish–American War. Following the latter war, he became ...

and First Lieutenant George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his class, b ...

to brigadier general.

Pleasonton corresponded with the congressman and complained about his lack of men and horses in comparison to Jeb Stuart's; he also politicked to acquire the cavalry forces of Maj. Gen. Julius Stahel

Julius H. Stahel-Számwald (born Gyula Számwald; November 5, 1825 – December 4, 1912) was a Hungarian soldier who emigrated to the United States and became a Union general in the American Civil War. After the war, he served as a U.S. diplomat, ...

, who commanded the cavalry in the defenses of Washington. The machinations worked. Stahel was relieved of his command and his troopers were reassigned to Pleasonton. Hooker was enraged by these activities and it was probably only his own relief from command on June 28, 1863, that saved Pleasonton's career from premature termination.

In the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Po ...

, Pleasonton's new commander, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was a United States Army officer and civil engineer best known for decisively defeating Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg in the American Civil War. H ...

, understood Pleasonton's reputation (and his father's) and kept him on a short leash. For the three days of the battle, Pleasonton was forced to remain with Meade at army headquarters, rather than with the Cavalry Corps headquarters nearby, and Meade exercised more direct control of the cavalry than an army commander normally would. In postwar writings, Pleasonton attempted to portray his role in the battle as being a major one, including predicting to Meade that the town of Gettysburg would be the decisive point and, after the Confederate defeat in Pickett's Charge

Pickett's Charge (July 3, 1863), also known as the Pickett–Pettigrew–Trimble Charge, was an infantry assault ordered by Confederate General Robert E. Lee against Major General George G. Meade's Union positions on the last day of the B ...

, that he urged Meade to attack Gen. Lee and finish him off. He conveniently made these claims after Meade's death, when dispute was impossible. On the other hand, however, Pleasonton cannot be blamed for the unfortunate cavalry action on July 3, when Meade ordered the division of Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick

Hugh Judson Kilpatrick (January 14, 1836 – December 4, 1881) was an officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War, achieving the rank of Brevet (military), brevet Major general (United States), major general. He was later the United S ...

to attack the right flank of the Confederate army, which resulted in a suicidal assault against entrenched infantry and the futile death of Brig. Gen. Elon Farnsworth

Elon John Farnsworth (July 30, 1837 – July 3, 1863) was a Union Army captain in the American Civil War. He commanded Brigade 1, Division 3 of the Cavalry Corps (Union Army) from June 28, 1863 to July 3, 1863, when he was mortally wounded and die ...

. After Pleasonton was removed the field, Meade was impressed with his performance from headquarters as an acting chief of staff during the battle.Longacre, 1986, p. 273.

Trans-Mississippi

Pleasonton was transferred to the Trans-Mississippi Theater and commanded the District of Central Missouri and the District of

Pleasonton was transferred to the Trans-Mississippi Theater and commanded the District of Central Missouri and the District of St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

on July 4, 1864. He performed well and over a period of four days, defeated Gen. Sterling Price

Major-General Sterling "Old Pap" Price (September 14, 1809 – September 29, 1867) was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army who commanded infantry in the Western and Trans-Mississippi theaters of the American Civil War. Prior to ...

at the Westport, the Battle of Byram's Ford

The Battle of Byram's Ford (also known as the Battle of Big Blue River and the Battle of the Blue) was fought on October 22 and 23, 1864, in Missouri during Price's Raid, a campaign of the American Civil War. With the Confederate States of ...

, the Battle of Mine Creek

The Battle of Mine Creek, also known as the Battle of the Osage, was fought on October 25, 1864, in Linn County, Kansas, as part of Price's Missouri Expedition during the American Civil War. Major General Sterling Price of the Confederate Stat ...

, and the Marais des Cygnes, ending the last Confederate threat in the West. He was injured by a fall in October 1864.

In 1864 and 1865, he instituted a policy of amnesty

Amnesty (from the Ancient Greek ἀμνηστία, ''amnestia'', "forgetfulness, passing over") is defined as "A pardon extended by the government to a group or class of people, usually for a political offense; the act of a sovereign power offici ...

, granting parole

Parole (also known as provisional release or supervised release) is a form of early release of a prison inmate where the prisoner agrees to abide by certain behavioral conditions, including checking-in with their designated parole officers, or ...

to Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

prisoners on condition they go up the Missouri River to the Dakota

Dakota may refer to:

* Dakota people, a sub-tribe of the Sioux

** Dakota language, their language

Dakota may also refer to:

Places United States

* Dakota, Georgia, an unincorporated community

* Dakota, Illinois, a town

* Dakota, Minnesota, ...

and Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

Territories. This resulted in preventing many of the remnants of Price's army from becoming bushrangers, like Quantrill, and also resulted in Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

Confederates migrating to the goldfields of the Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

Territory.

On April 10, 1866, President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

nominated Pleasonton for appointment as a brevet brigadier general in the regular army for the campaign in Missouri, to rank from March 13, 1865, and the U.S. Senate confirmed the appointment on May 4, 1866 (and July 14, 1866, after changes in the date of rank for brevet appointments for non-field service). On July 17, 1866, President Johnson nominated Pleasonton for appointment as a brevet major general in the regular army for his overall conduct in the war, to rank from March 13, 1865, and the U.S. Senate confirmed the appointment on July 23, 1866.

Postbellum career

After the war, although Pleasonton had achieved the honorary rank of brevet major general in the regular army, he was mustered out of the volunteer service with the permanent rank of major of cavalry. Because he did not want to leave the cavalry, Pleasonton turned down a lieutenant colonel in the infantry, and soon became dissatisfied with his command relationship to officers he once outranked. Pleasonton resigned his commission in 1868, and was placed on the Army's retired list as a major in 1888. As a civilian, he worked as United States Collector of Internal Revenue and as

After the war, although Pleasonton had achieved the honorary rank of brevet major general in the regular army, he was mustered out of the volunteer service with the permanent rank of major of cavalry. Because he did not want to leave the cavalry, Pleasonton turned down a lieutenant colonel in the infantry, and soon became dissatisfied with his command relationship to officers he once outranked. Pleasonton resigned his commission in 1868, and was placed on the Army's retired list as a major in 1888. As a civilian, he worked as United States Collector of Internal Revenue and as Commissioner of Internal Revenue

The Commissioner of Internal Revenue is the head of the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), an agency within the United States Department of the Treasury.

The office of Commissioner was created by Congress as part of the Revenue Act of 1862. Section ...

under President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

, but he was asked to resign from the Bureau of Internal Revenue (now the Internal Revenue Service

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is the revenue service for the United States federal government, which is responsible for collecting U.S. federal taxes and administering the Internal Revenue Code, the main body of the federal statutory ta ...

) after he lobbied Congress for the repeal of the income tax and quarreled with his superiors at the Treasury Department. Refusing to resign, he was dismissed. He served briefly as the president of the Terre Haute and Cincinnati Railroad.

In an 1895 interview with sculptor James Edward Kelly, Pleasonton claimed he had been offered command of the Army of the Potomac. (A subsequent interview with Gen. James F. Wade indicated that this offer came in a meeting in Washington some time after Gettysburg.) Pleasonton told Kelly that he "wasn't like Grant

Grant or Grants may refer to:

Places

*Grant County (disambiguation)

Australia

* Grant, Queensland, a locality in the Barcaldine Region, Queensland, Australia

United Kingdom

*Castle Grant

United States

* Grant, Alabama

*Grant, Inyo County, C ...

. I refused to pay the price." He claimed that the terms offered were: "The war must not be ended until the South was crushed; slavery abolished; and the President reelected." Pleasonton, always more of a bureaucrat than an ideologue or strong leader, only wanted to defeat the South's military capabilities so that they could not threaten the rest of the states, but was not convinced that "crushing" the rebels, ending slavery, or reelecting Lincoln was worth the cost.

Alfred Pleasonton died in his sleep in Washington, D.C., on January 17, 1897, and is buried in the Congressional Cemetery

The Congressional Cemetery, officially Washington Parish Burial Ground, is a historic and active cemetery located at 1801 E Street, SE, in Washington, D.C., on the west bank of the Anacostia River. It is the only American "cemetery of national m ...

there, alongside his father. Before his death, Pleasonton requested that his funeral be devoid of all military honors and even refused to be buried in his old uniform because he felt the Army passed him over after the Civil War.

The town of Pleasanton, California

Pleasanton is a city in Alameda County, California, United States. Located in the Amador Valley, it is a suburb in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area. The population was 79,871 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census. In 200 ...

, was named for Alfred in the late 1860s; a typographical error by a U.S. Postal Service

The United States Postal Service (USPS), also known as the Post Office, U.S. Mail, or Postal Service, is an independent agency of the executive branch of the United States federal government responsible for providing postal service in the U. ...

employee apparently led to the spelling difference. The city of Pleasanton, Kansas

Pleasanton is a city in Linn County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 1,208.

History

In 1864, General Alfred Pleasonton defeated the Confederates in the Battle of Mine Creek near present-day Pleasant ...

, also named for Pleasonton, held its first "General Pleasonton Days" celebration in 2007. On the huge Pennsylvania Memorial at the Gettysburg Battlefield

The Gettysburg Battlefield is the area of the July 1–3, 1863, military engagements of the Battle of Gettysburg within and around the borough of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Locations of military engagements extend from the site of the first shot ...

stands a statue of General Pleasonton. However, it is possible that this represents Alfred's brother, Augustus, a native of Pennsylvania, who was a general in the Pennsylvania militia at the time of the battle./ref>

See also

*List of American Civil War generals (Union)

Union generals

__NOTOC__

The following lists show the names, substantive ranks, and brevet ranks (if applicable) of all general officers who served in the United States Army during the Civil War, in addition to a small selection of lower-ranke ...

References

Informational notes Citations Bibliography * Custer, Andie. "The Knight of Romance". ''Blue & Gray'' magazine (Spring 2005), p. 7. * Eicher, John H., andDavid J. Eicher

David John Eicher (born August 7, 1961) is an American editor, writer, and popularizer of astronomy and space. He has been editor-in-chief of ''Astronomy'' magazine since 2002. He is author, coauthor, or editor of 23 books on science and American ...

, ''Civil War High Commands''. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. .

* Holland, Jr., Francis Ross''America's Lighthouses''

Courier Corp., 2012. (New York: Dover Maritime, 1988) . pp. 26–35. Retrieved May 18, 2015. * Longacre, Edward G. ''The Cavalry at Gettysburg: A Tactical Study of Mounted Operations during the Civil War's Pivotal Campaign, 9 June–14 July 1863''. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986. . * Longacre, Edward G. ''Lincoln's Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of the Potomac''. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000. . * Styple, William B. ''Generals in Bronze: Interviewing the Commanders of the Civil War''. Kearny, NJ: Belle Grove Publishing, 2005. . * Taaffe, Stephen R. ''Commanding the Army of the Potomac''. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 2006. .

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Pleasonton, Alfred 1824 births 1897 deaths 19th-century American railroad executives American military personnel of the Mexican–American War Burials at the Congressional Cemetery Cavalry commanders Commissioners of Internal Revenue People from Washington, D.C. People of Washington, D.C., in the American Civil War Pleasanton, California Union Army generals United States Military Academy alumni