Alexander Murray Dunlop on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

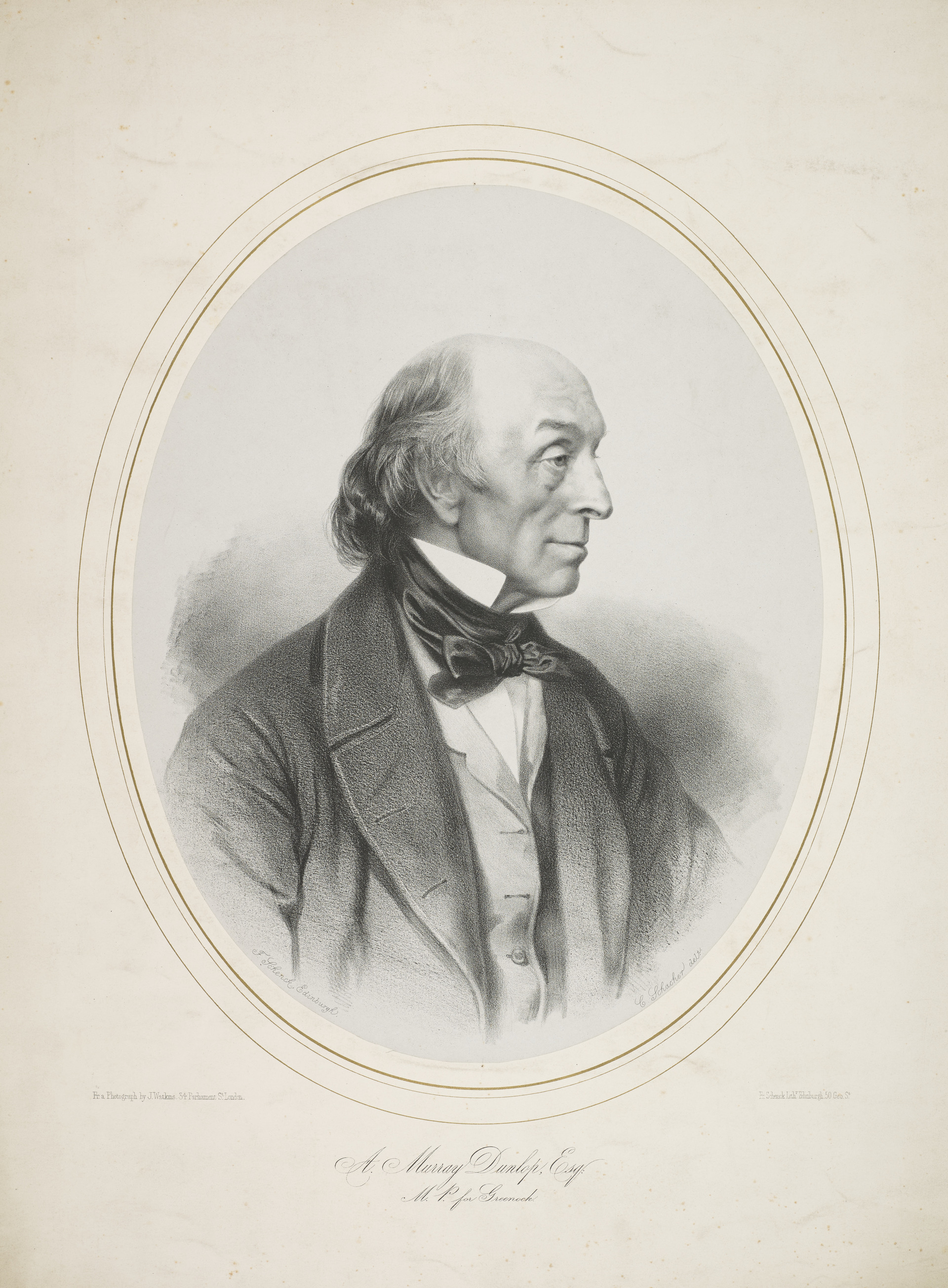

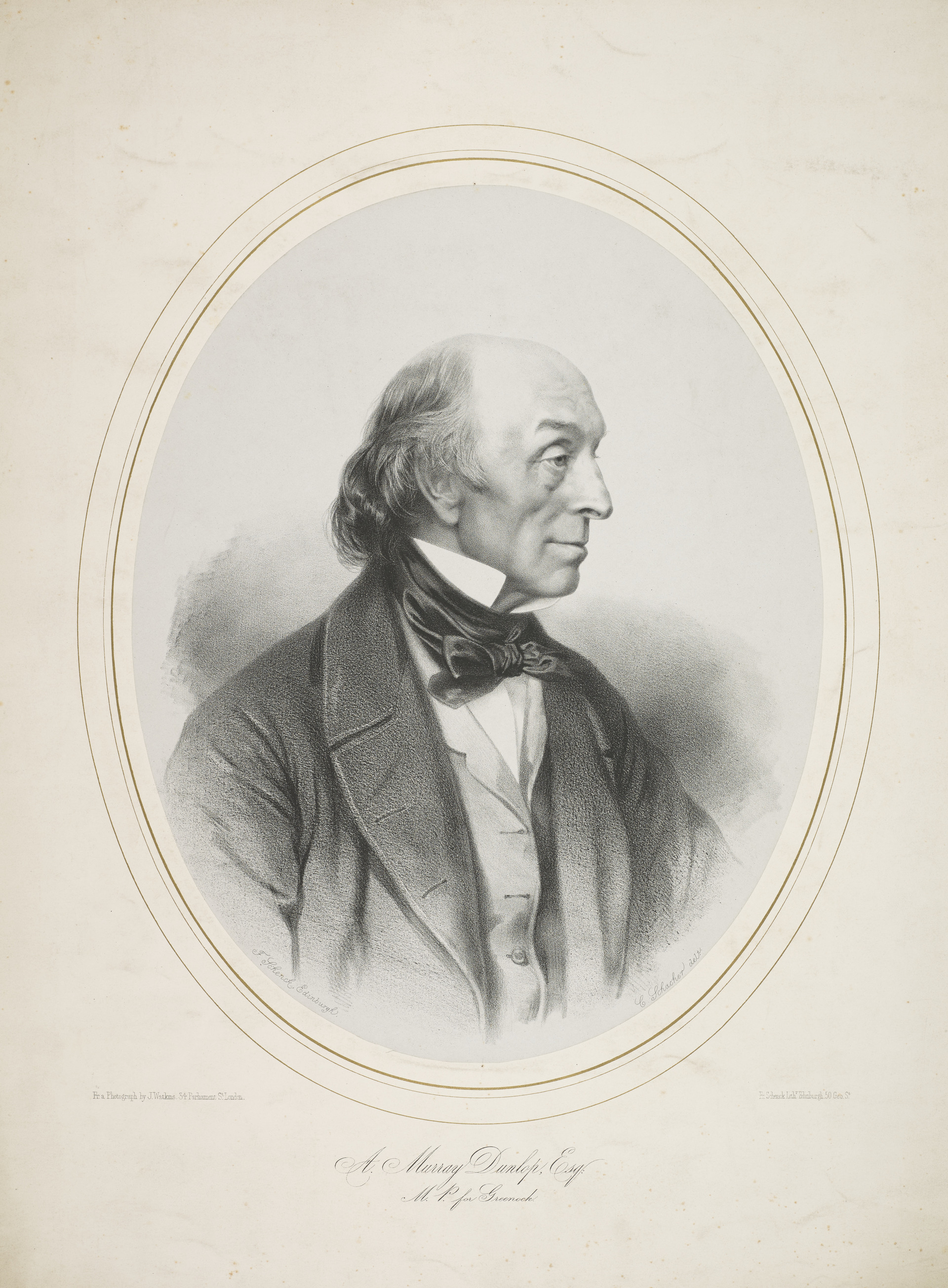

Alexander Colquhoun-Stirling-Murray-Dunlop (27 December 1798 – 1 September 1870) was a Scottish church advocate and

Alexander Colquhoun-Stirling-Murray-Dunlop (27 December 1798 – 1 September 1870) was a Scottish church advocate and

Alexander Murray Dunlop was born in

Alexander Murray Dunlop was born in

accessed 14 Oct 2017

/ref>

Alexander Colquhoun-Stirling-Murray-Dunlop (27 December 1798 – 1 September 1870) was a Scottish church advocate and

Alexander Colquhoun-Stirling-Murray-Dunlop (27 December 1798 – 1 September 1870) was a Scottish church advocate and Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

politician. He was the Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

(MP) for Greenock

Greenock (; sco, Greenock; gd, Grianaig, ) is a town and administrative centre in the Inverclyde council areas of Scotland, council area in Scotland, United Kingdom and a former burgh of barony, burgh within the Counties of Scotland, historic ...

from 1852 to 1868. He was a very influential figure in the Disruption of 1843

The Disruption of 1843, also known as the Great Disruption, was a schism in 1843 in which 450 evangelical ministers broke away from the Church of Scotland to form the Free Church of Scotland.

The main conflict was over whether the Church of S ...

which led to the formation of the Free Church of Scotland. For that denomination he drafted the Church-State papers: the Claim of Right and the Protest. He became known by the nickname the Member for Scotland.

Early life and career

Alexander Murray Dunlop was born in

Alexander Murray Dunlop was born in Greenock

Greenock (; sco, Greenock; gd, Grianaig, ) is a town and administrative centre in the Inverclyde council areas of Scotland, council area in Scotland, United Kingdom and a former burgh of barony, burgh within the Counties of Scotland, historic ...

on 27 December 1798. He was the fifth son of Alexander Dunlop of Keppoch, Dunbartonshire, by Margaret Colquhoun of Kenmure, Lanarkshire. His family had in former times taken much interest in the Scottish church. He was educated at the Grammar School of that town, and at the University of Edinburgh. At university he was a member of The Speculative Society

The Speculative Society is a Scottish Enlightenment society dedicated to public speaking and literary composition, founded in 1764. It was mainly, but not exclusively, an Edinburgh University student organisation. The formal purpose of the Societ ...

. After the usual attendance on the classes in the faculties of Arts and of Law, Dunlop was called to the bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

in 1820, and in his earliest years was an ardent student of his profession. In 1822 he became one of the editors of 'Shaw and Dunlop's Reports', and gave evidence of his legal attainments. At an early period his attention was specially directed to parochial law; in 1825 he published a treatise on the law of Scotland relating to the poor, in 1833 a treatise on the law of patronage, and afterwards his fuller treatise on parochial law. He later published some of David Welsh's sermons with a (138-page) memoir and a memoir of Alexander Earle Monteith. Welsh had been a private tutor to Dunlop.

Interest in church law

The year 1832 saw the beginning of Mr Dunlop's public life. He became really well known and a confidential leader, just when the party in the Church which he supported became dominant in the Assembly. His great knowledge of old Scotch law, especially in its bearing on,the relation between Church and State, as well as his powers of clear thought and expression, made his services sought after. He was the mediator in many disputes, the confidant in many plan, the active manager in many of the more important matters of popular Church business. His correspondence on public affairs soon grew very voluminous. He was an active member of the various Church societies — of the Church Law Society, of the Anti-Patronage Society, for example —and his whole time was occupied in the business which Church affairs brought upon him. In 1833 he was busiest with the Chapel Act, and was actively engaged in promoting anti-patronage meetings; in 1834 he became editor of the "Presbyterian Review. In 1835 Church extension occupied him; in 1837 and 1838 the Auchterarder case, the conflict between the Church and the Court of Session, and non-intrusion meetings, absorbed his attention. The sympathies of Dunlop were very warmly enlisted in the operations of the church, and he took an active part in all the ecclesiastical reforms and benevolent undertakings of the period. But in a pre-eminent degree his interest was excited by the questions relating to the law of patronage, and the collision which arose out of them between the church and the civil courts. Relying on history and statute, Dunlop very earnestly supported what was called the "non-intrusion" party, led byThomas Chalmers

Thomas Chalmers (17 March 178031 May 1847), was a Scottish minister, professor of theology, political economist, and a leader of both the Church of Scotland and of the Free Church of Scotland. He has been called "Scotland's greatest nine ...

and others, believing it to be constitutionally in the right, and when the church became involved in litigation he devoted himself with rare disinterestedness to her defence. He not only defended the church at the bar of the court of session, but in private councils, in committees, deputations, and publications he was unwearied on her behalf. The public documents in which his position was stated and defended, especially the Claim of Right in 1842, the Protest and Deed of Demission in 1843, were mainly his work.

Church of Scotland elder

Dunlop became an elder in the Church of Scotland in Greenock in 1822. On going to Edinburgh he became a member of the kirk-session in St Bernard's church. This made it possible for him to take part in the General Assemblies and other church courts. From 1845 he was an elder at Free St Georges, Edinburgh. Among Church reforms Mr Dunlop took special interest in the restoration of the eldership to its old place in the Church of Scotland. He wrote two articles upon this subject in the "Presbyterian Review," and prepared an elaborate report for the General Assembly. He also left some historical notes upon the place of the eldership in the ancient Church of Scotland, which were not published in his lifetime. Church extension, too, interested him greatly; but, as was natural from his previous studies, the relation of the Church to education and to the poor occupied most of his attention. The inforrnation furnished by the Church to the Government about the number of paupers in Scotland, and the elaborate Report on the same subject presented to the Assembly of 1841, were both the result of Mr Dunlop's almost unaided labour. He took an active part in the Voluntary controversy.The Claim of Right

His argument, the same in speech and pamphlet, and at last set forth in detail in the Claim of Rights, was substantially this: There is no need in Scotland to dispute about the precise meaning and effects of the abstract doctrine of spiritual independence. In virtue of a concordat between Church and State, the Church of Scotland has had certain rights and liberties which can be enumerated, guaranteed her, and recognised as hers. These she claims to possess, not merely by inherent right, but also by legal recognition, and these are now being illegally wrested from her. Originally in the form of an "Overture," this paper, when adopted by the Church of Scotland General Assembly on the motion ofThomas Chalmers

Thomas Chalmers (17 March 178031 May 1847), was a Scottish minister, professor of theology, political economist, and a leader of both the Church of Scotland and of the Free Church of Scotland. He has been called "Scotland's greatest nine ...

, and carried by a majority of 131 in 1842, became the " Claim, Declaration, and Protest, anent the encroachments of the Court of Session," a title which is often abbreviated "The Claim of Right". After a preamble containing eighteen paragraphs, dealing with historical and legal details, the manifesto formulates the Church's "Claim" to possess and exercise her liberties, government, discipline, rights and privileges according to law; her "Declaration" that it is impossible for her to intrude ministers on reclaiming congregations, or carry on the government of Christ's Church subject to the coercion attempted by the Court of Session; and her "Protest" that all acts of the Parliament of Great Britain passed without the consent of this Church and nation, in alteration of, or derogation to, the government, discipline, rights and privileges of this Church, as also all sentences of Courts in contravention of the same are, and shall be, in themselves void and null, and of no legal force or effect. The document concludes with an invitation to all the office-bearers and members of this Church, who are willing to suffer for their allegiance to their adorable King and Head, to stand by the Church and by each other, in defence of the great doctrine of the sole Headship of the Lord Jesus over His Church, and of the liberties and privileges, whether of office-bearers or people, which rest upon it ; and to unite in supplications to Almighty God that He would be pleased to turn the hearts of the rulers of this kingdom to keep unbroken the faith pledged to this Church in former days, and the obligations, come under to God Himself, to preserve and maintain the government and discipline of this Church in accordance with His Word ; or otherwise, that He would give strength to this Church to endure resignedly the loss of the temporal benefits of an Establishment, and the personal sufferings and sacrifices to which they may be called ; and that, in His own good time, He would restore to them these benefits, the fruits of the struggles and sufferings of their fathers in times past in the same cause; and thereafter give them grace to employ them more effectually than hitherto they have done for the manifestation of His glory.

On January 4 1843, a reply was received from the Crown, signed by Sir James Graham, pronouncing the Church's claim to be "unreasonable."

At the Disruption

On 7 March, 1843, the Claim of Rights was finally brought before the House of Commons by Foxe Maule in the British Parliament. Maule's motion for a Committee of Inquiry was lost upon a division, by 211 votes to 76. Of 36 Scottish members present, 25 voted with Maule. Following this the General Assembly met on 18 May, 1843, within a large hall at Canonmills, Edinburgh. The Moderator,David Welsh

David Welsh FRSE (11 December 179324 April 1845) was a Scottish divine and academic. He was Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1842. In the Disruption of 1843 he was one of the leading figures in the establishmen ...

,prayed, made some comments and then read a Protest which was again largely written by Dunlop. As soon as it was read Welsh handed the paper to the clerk, quitted the chair, and walked away. In all 193 members moved off, of whom about 123 were ministers and about 70 elders. All, including Dunlop, withdrew slowly and regularly amidst perfect silence till that side of the house was left nearly empty. They were joined outside by a large body of adherents, among whom were about 300 clergymen. They walked through the streets to Tanfield Hall where a Free Church Assembly had been organised. Following this Free Church Assembly another two legal documents the Act of Separation and Deed of Demission, were signed and registered in the books of Council and Session, on 8 June, 1843.

Changes of name

In 1844, he married Eliza Esther, only child of John Murray of Ainslie Place, Edinburgh, and on the death of his father-in-law in 1849, he assumed the name of Murray-Dunlop. Subsequently, in 1866, on succeeding to the estate of his cousin, William Colquhoun-Stirling of Law and Edinbarnet, he took the name of Colquhoun-Stirling-Murray-Dunlop. He received an honourary LLD fromPrinceton University

Princeton University is a private university, private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial Colleges, fourth-oldest ins ...

.

Political career

In 1845 and 1847, he contested the representation of his native town ofGreenock

Greenock (; sco, Greenock; gd, Grianaig, ) is a town and administrative centre in the Inverclyde council areas of Scotland, council area in Scotland, United Kingdom and a former burgh of barony, burgh within the Counties of Scotland, historic ...

, but without success; in 1852, he was returned by the electors, and for fifteen years represented them. In early life he had been a tory, but he was now thoroughly liberal. In parliament, however, while generally supporting the liberals he retained an independent position, declining offices both in connection with the government and with his own profession in Scotland, to which his services and abilities well entitled him.

His services in parliament were fruitful of much useful legislation. In a sketch of his life by his friend, David Maclagan

David Maclagan FRSE (8 February 1785 – 6 June 1865) was a prominent Scottish medical doctor and military surgeon, serving in the Napoleonic Wars. He served as President of both the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh and the Royal Colle ...

, mention is made of eight various acts which he got passed. Those on legal points introduced important practical amendments of the laws, the most interesting, perhaps, being that which put a stop to Gretna Green

Gretna Green is a parish in the southern council area of Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, on the Scottish side of the border between Scotland and England, defined by the small river Sark, which flows into the nearby Solway Firth. It was historica ...

marriages. Some of his measures bore on social improvement, one of them being an act to facilitate the erection of dwelling-houses for the working classes, and another an act to render reformatories and industrial schools more available for vagrant and destitute children, well known as Dunlop's Act. Another allowed orphans to inherit from their parents rather than the estate being divided by next of kin.

In the "Arrow" affair, he testified his abhorrence of the conduct of the Liberal Government in the war with China in 1857. The defeat of the Ministry involved a general election, and it was felt that many of the Liberals who had voted against the Government would lose their seats. Mr Dunlop at once placed his resignation in the hands of his constituency, and declared, with his usual high sense of honour, that he would not even stand as a candidate if they disapproved of his conduct.

The most chivalrous of his parliamentary services was an attack (19 March 1861) on the government of Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865) was a British statesman who was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century. Palmerston dominated British foreign policy during the period ...

, which he had usually supported, in connection with the Afghan war. Many years after the event, it was ascertained that certain despatches written in 1839 by Sir Alexander Burnes

Captain Sir Alexander Burnes (16 May 1805 – 2 November 1841) was a Scottish explorer, military officer, and diplomat associated with the Great Game. He was nicknamed Bokhara Burnes for his role in establishing contact with and expl ...

, our envoy at the Afghan court, had been tampered with in publication, and made to express opinions opposite to those which Sir Alexander held. Dunlop, at a great sacrifice of feeling, moved on 19 March 1861 for a committee of inquiry, and was very ably supported by Mr. Bright and others. Lord Palmerston was put to great straits in his defence, as it could not be denied that Burnes's despatches had been changed; but Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a central role in the creation o ...

came to his rescue, and on the ground that the matter was now twenty years old advised the house not to reopen it. On a division, the motion of Dunlop was negatived by a vote of 159 to 49.

In 1868, he resigned his seat in parliament, the rest of his days being spent chiefly on his property of Corsock

Corsock ( gd, Corsag) is a village in the historical county of Kirkcudbrightshire, Dumfries and Galloway, south-west Scotland. It is located north of Castle Douglas, and the same distance east of New Galloway, on the Urr Water.

Corsock House i ...

in Dumfriesshire. Lord Cockburn

Henry Thomas Cockburn of Bonaly, Lord Cockburn ( ; Cockpen, Midlothian, 26 October 1779 – Bonaly, Midlothian, 26 April/18 July 1854) was a Scottish lawyer, judge and literary figure. He served as Solicitor General for Scotland between 1830 an ...

in his "Journal" ranks Dunlop in everything, except impressive public exhibition, superior to Thomas Chalmers

Thomas Chalmers (17 March 178031 May 1847), was a Scottish minister, professor of theology, political economist, and a leader of both the Church of Scotland and of the Free Church of Scotland. He has been called "Scotland's greatest nine ...

and Robert Smith Candlish

Robert Smith Candlish (23 March 1806 – 19 October 1873) was a Scottish minister who was a leading figure in the Disruption of 1843. He served for many years in both St. George's Church and St George's Free Church on Charlotte Square in Edinb ...

:

Dunlop died on 1 September 1870, in age seventy-one.

Family

In 1844, Dunlop married Eliza Esther Murray, only child of John Murray of Edinburgh. She died at Corsock on 14 July 1902, 84 years old. They had four sons and four daughters. Their eldest daughter was Anna Lindsay whose name was said to be synonymous with women's rights in Scotland.K. D. Reynolds, 'Lindsay , Anna (1845–1903)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 200accessed 14 Oct 2017

/ref>

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ;Attribution * **Notice of the late Mr. Dunlop, by Mr. David Maclagan **Hansard's Debates **Scotsman and Daily Review, 2 September 1870 **Funeral Sermons, by Rev. Dr. J. Julius Wood and Rev. Dr. Candlish **personal recollections and letters from Mr. Dunlop's family to the writer.External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Dunlop, Alexander Colquhoun-Stirling-Murray- 1798 births 1870 deaths People from Greenock Scottish lawyers Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for Scottish constituencies Scottish Liberal Party MPs UK MPs 1852–1857 UK MPs 1857–1859 UK MPs 1859–1865 UK MPs 1865–1868 Free Church of Scotland people