Aleksey Suvorin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Aleksei Sergeyevich Suvorin (Russian: Алексей Сергеевич Суворин, 11 September 1834, Korshevo,

Aleksei Sergeyevich Suvorin (Russian: Алексей Сергеевич Суворин, 11 September 1834, Korshevo,

In 1876, Suvorin acquired ownership of the failing newspaper '' Novoye Vremya'' ("New Times"); he remained the editor in chief until his death. In 1880, he founded a reputable historical journal, ''

In 1876, Suvorin acquired ownership of the failing newspaper '' Novoye Vremya'' ("New Times"); he remained the editor in chief until his death. In 1880, he founded a reputable historical journal, ''

Ever since the 1860s, Suvorin had been interested in theatre and regularly published theatrical criticism. He befriended

Ever since the 1860s, Suvorin had been interested in theatre and regularly published theatrical criticism. He befriended Tovstonogov Drama Theatre

Encyclopaedia of St. Petersburg

{{DEFAULTSORT:Suvorin, Alexey 1834 births 1912 deaths People from Bobrovsky District People from Bobrovsky Uyezd Members of the Russian Assembly Journalists from the Russian Empire 19th-century newspaper publishers (people) Russian newspaper publishers (people) Russian book publishers (people) Russian nationalists Burials at Nikolskoe Cemetery 19th-century journalists from the Russian Empire

Voronezh Governorate

Voronezh Governorate (russian: Воронежская губерния, ''Voronezhskaya guberniya''; uk, Воронізька губернія) was an administrative division (a '' guberniya'') of the Tsardom of Russia, the Russian Empire, and th ...

– 11 August 1912, Tsarskoye Selo

Tsarskoye Selo ( rus, Ца́рское Село́, p=ˈtsarskəɪ sʲɪˈlo, a=Ru_Tsarskoye_Selo.ogg, "Tsar's Village") was the town containing a former residence of the Russian imperial family and visiting nobility, located south from the c ...

) was a Russian newspaper and book publisher

Publishing is the activity of making information, literature, music, software and other content available to the public for sale or for free. Traditionally, the term refers to the creation and distribution of printed works, such as books, newsp ...

and journalist

A journalist is an individual that collects/gathers information in form of text, audio, or pictures, processes them into a news-worthy form, and disseminates it to the public. The act or process mainly done by the journalist is called journalism ...

whose publishing empire wielded considerable influence during the last decades of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

.

He set out as a liberal journalist but, like many of his contemporaries, he experienced a dramatic shift in views, gradually drifting towards nationalism.

Early career

Suvorin was a quintessential selfmade man. Born of a peasant family, he succeeded in gaining access to a military school atVoronezh

Voronezh ( rus, links=no, Воро́неж, p=vɐˈronʲɪʂ}) is a city and the administrative centre of Voronezh Oblast in southwestern Russia straddling the Voronezh River, located from where it flows into the Don River. The city sits on ...

from which he graduated in 1850. In the following year, he arrived in St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

and joined a major artillery school there. With limited prospects of pursuing a military career, he spent eight years in his native haunts, teaching history and geography, first in Bobrov and then in Voronezh. No one could have predicted that within two or three decades, the provincial teacher would rise to become one of the most influential men in the empire.

A major step forward in his career was in 1861, when, electrified by the Emancipation Manifesto, he relocated to Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, where he found himself at the periphery of a burgeoning literary scene. At first money was tight, instigating Suvorin to move to St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, where he joined the staff of the '' St. Petersburg Vedomosti'', an influential newspaper with liberal leanings. He soon became its leading contributor and secretary to the editor in chief. Suvorin's ''feuilleton

A ''feuilleton'' (; a diminutive of french: feuillet, the leaf of a book) was originally a kind of supplement attached to the political portion of French newspapers, consisting chiefly of non-political news and gossip, literature and art criticis ...

s'', published under the pen name "Stranger", were an instant sensation and inspired him to turn his attention to more creative writing.

Publishing

Suvorin's personality as a writer is somewhat overshadowed by his journalism. Nevertheless, he was very prolific and published a number of short stories and plays in the major outlets of the liberal media of which he was considered a leader. Capitalising on that success, Suvorin set up a publishing venture in 1871. Among his first publications was the ''Russian Calendar'', which was in high demand all over Russia, followed by an unprecedented series of cheap editions of classics, both foreign and Russian. For more demanding readers, he issued a suite of richly illustrated albums about the great art galleries of Europe. In the late 19th century, he launched a series ofcity directories

A city directory is a listing of residents, streets, businesses, organizations or institutions, giving their location in a city. It may be arranged alphabetically or geographically or in other ways. Antedating telephone directories, they were i ...

, published on an annual basis (each were between 500 and 1500 pages long) for St. Petersburg, Moscow and the rest of Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eigh ...

that detailed the names and addresses of private residents, government offices, public services and medium and large businesses. They are often referred to as the Suvorin directories, from the publisher's name. The directories are often used by modern genealogists

Genealogy () is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kins ...

to trace family members who lived in Imperial and early Soviet Russia when vital records

Vital records are records of life events kept under governmental authority, including birth certificates, marriage licenses (or marriage certificates), separation agreements, divorce certificates or divorce party and death certificates. In ...

are missing or prove difficult to find. Historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the st ...

s use them to research the social histories of late 19th century and early 20th century Russia.

By the end of the century, Suvorin's bookstores were everywhere, in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Kharkov

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

, Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrat ...

, Rostov

Rostov ( rus, Росто́в, p=rɐˈstof) is a town in Yaroslavl Oblast, Russia, one of the oldest in the country and a tourist center of the Golden Ring. It is located on the shores of Lake Nero, northeast of Moscow. Population:

While ...

, Saratov

Saratov (, ; rus, Сара́тов, a=Ru-Saratov.ogg, p=sɐˈratəf) is the largest city and administrative center of Saratov Oblast, Russia, and a major port on the Volga River upstream (north) of Volgograd. Saratov had a population of 901 ...

. He held a monopoly on the distribution of printed matter on the railway stations and trains, and he was probably the most influential publisher in the country.

''Novoye Vremya''

In 1876, Suvorin acquired ownership of the failing newspaper '' Novoye Vremya'' ("New Times"); he remained the editor in chief until his death. In 1880, he founded a reputable historical journal, ''

In 1876, Suvorin acquired ownership of the failing newspaper '' Novoye Vremya'' ("New Times"); he remained the editor in chief until his death. In 1880, he founded a reputable historical journal, ''Istorichesky Vestnik

''Istorichesky Vestnik'' (russian: Историческій Вѣстникъ, Исторический вестник, History Herald) was a Russian monthly historical and literary magazine published in Saint Petersburg in 1880-1917.Mikhail Katkov

Mikhail Nikiforovich Katkov (russian: Михаи́л Ники́форович Катко́в; 13 February 1818 – 1 August 1887) was a conservative Russian journalist influential during the reign of tsar Alexander III. He was a proponent of Rus ...

and Konstantin Pobedonostsev

Konstantin Petrovich Pobedonostsev ( rus, Константи́н Петро́вич Победоно́сцев, p=kənstɐnʲˈtʲin pʲɪˈtrovʲɪtɕ pəbʲɪdɐˈnostsɨf; 30 November 1827 – 23 March 1907) was a Russian jurist, statesman ...

. ''Novoye Vremya'' enthusiastically supported the policies of anti-Semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

and russification

Russification (russian: русификация, rusifikatsiya), or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians, whether involuntarily or voluntarily, give up their culture and language in favor of the Russian cultur ...

promoted by the government of Alexander III.

In his book on the Russian Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

, one of the former leaders of that revolution, Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian M ...

, described Suvorin's hatred for even the very idea of revolution, which Suvorin portrayed in a bizarrely twisted misogynistic way: "'Revolution,' old Suvorin, that arch-reptile of the Russian bureaucracy, wrote at the end of November 905

__NOTOC__

Year 905 ( CMV) was a common year starting on Tuesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Europe

* Spring – King Berengar I of Italy arranges a truce with the Hungarians, on ...

'gives an extraordinary elan to men and gains a multitude of devoted, fanatical adherents who are prepared to sacrifice their lives. The struggle against revolution is so difficult precisely because it has so much fervor, courage, sincere eloquence, and ardent enthusiasm to contend with. The stronger the enemy, the more resolute and courageous revolution becomes, and with every victory it attracts a swarm of admirers. Anyone who does not know this, who does not know that revolution is attractive like a young, passionate woman with arms flung wide, showering avid kisses on you with hot, feverish lips, has never been young.'"

During Suvorin's declining years, Vasily Rozanov

Vasily Vasilievich Rozanov (russian: Васи́лий Васи́льевич Рóзанов; – 5 February 1919) was one of the most controversial Russian writers and important philosophers in the symbolists' of the pre- revolutionary epoc ...

and several other popular journalists of his newspaper were allowed considerable discretion in airing their idiosyncratic views. They pioneered a new style of adversary journalism, which frequently bordered on personal attacks.

Suvorin's intense dislike of reform and reformers was deeply entrenched: back in 1873, his first wife had been shot dead by her lover, a liberal officer who proceeded to commit suicide. Another influence was Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (, ; rus, Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский, Fyódor Mikháylovich Dostoyévskiy, p=ˈfʲɵdər mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ dəstɐˈjefskʲɪj, a=ru-Dostoevsky.ogg, links=yes; 11 November 18219 ...

, with whom he was on close terms, especially during the last year of the novelist's life. Suvorin was succeeded at the helm of the family business by one of his sons. His grave is in the Alexander Nevsky Lavra

Saint Alexander Nevsky Lavra or Saint Alexander Nevsky Monastery was founded by Peter I of Russia in 1710 at the eastern end of the Nevsky Prospekt in Saint Petersburg, in the belief that this was the site of the Neva Battle in 1240 when Ale ...

.

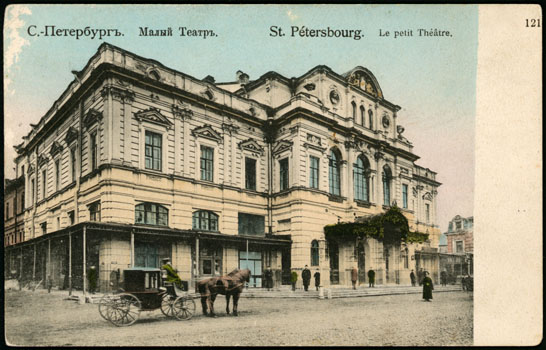

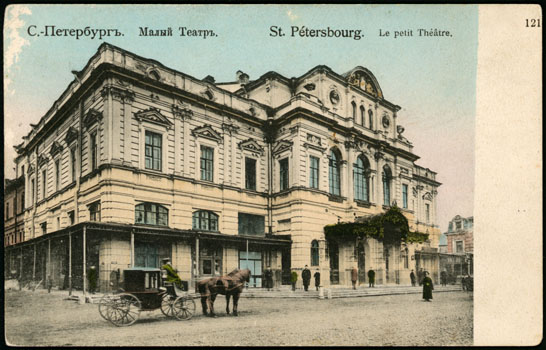

Suvorin Theatre

Ever since the 1860s, Suvorin had been interested in theatre and regularly published theatrical criticism. He befriended

Ever since the 1860s, Suvorin had been interested in theatre and regularly published theatrical criticism. He befriended Anton Chekhov

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (; 29 January 1860Old Style date 17 January. – 15 July 1904Old Style date 2 July.) was a Russian playwright and short-story writer who is considered to be one of the greatest writers of all time. His career a ...

, when the latter was an aspiring journalist and became one of his few intimates. Their extensive correspondence is captivating reading. It illustrates the evolution of Chekhov's views on all aspects of Russia's life over the years. It has been noted that Chekhov was so blinded by his affection towards Suvorin that he wrote a one-act sequel to his anti-Semitic play.

By the second half of the 1890s, when Chekhov finally distanced himself from Suvorin, the latter had plunged headlong into theatre. With secure financial backing, he launched his own stage company in 1895. His powerful connections allowed him to get the censorship lifted on Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

's ''The Power of Darkness'', which was premiered at his theatre. Before long, Suvorin's predilection for controversial pieces made his theatre unpopular with liberal elite

Liberal elite, also referred to as the metropolitan elite or progressive elite, is a stereotype of politically liberal people whose education has traditionally opened the doors to affluence, wealth and power and who form a managerial elite. It is ...

s. At the opening night of ''The Sons of Israel'' (1900), "the actors were pelted with apples, galoshes, and other missiles".Robert Leach, Viktor Borovsky. ''A History of Russian Theatre''. Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 248.

The reputation of Suvorin's theatre was so negative that after completing ''The Cherry Orchard

''The Cherry Orchard'' (russian: Вишнёвый сад, translit=Vishnyovyi sad) is the last play by Russian playwright Anton Chekhov. Written in 1903, it was first published by ''Znaniye'' (Book Two, 1904), and came out as a separate edition ...

'', Chekhov wrote to his wife that he would not give the play to Suvorin even if he offered him 100,000 rubles and that he despised Suvorin's establishment. Despite the negative publicity, the company survived its founder and continued to operate profitably until the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

, under the name Maly Imperial Theatre (Малый Императорский Театр). In retrospect, it appears to have been "the most important private theatre in St. Petersburg".

Since 1920, the building of the theatre, at 65 Fontanka

The Fontanka (russian: Фонтанка), a left branch of the river Neva, flows through the whole of Central Saint Petersburg, Russia – from the Summer Garden to . It is long, with a width up to , and a depth up to . The Moyka River ...

Embankment, became the home of Bolshoi Drama Theatre (now known as Tovstonogov Drama Theatre).References

;Inline ;General *Динерштейн Е.А. А.С. Суворин: Человек, сделавший карьеру. . Moscow, 1998. *Ambler, Effie. ''The Career of Aleksei S. Suvorin, Russian Journalism and Politics, 1861–1881''. Wayne State University Press, 1972.Encyclopaedia of St. Petersburg

{{DEFAULTSORT:Suvorin, Alexey 1834 births 1912 deaths People from Bobrovsky District People from Bobrovsky Uyezd Members of the Russian Assembly Journalists from the Russian Empire 19th-century newspaper publishers (people) Russian newspaper publishers (people) Russian book publishers (people) Russian nationalists Burials at Nikolskoe Cemetery 19th-century journalists from the Russian Empire