Alan Bush on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

At the RAM, Bush studied composition under Frederick Corder and piano with

At the RAM, Bush studied composition under Frederick Corder and piano with

After his 1928 concert tour in Berlin, Bush returned to the city to study piano under

After his 1928 concert tour in Berlin, Bush returned to the city to study piano under

At the end of summer 1931 the couple returned permanently to England, and settled in the village of Radlett, in Hertfordshire. In the following years three daughters were born. Bush resumed his RAM and LLCU duties, and in 1932 accepted a new appointment, as an examiner for the Associated Board of London's Royal Schools of Music, a post which involved extensive overseas travel. These new domestic and professional responsibilities limited Bush's composing activity, but he provided the music for the 1934 Pageant of Labour, organised for the London Trades Council and held at the

At the end of summer 1931 the couple returned permanently to England, and settled in the village of Radlett, in Hertfordshire. In the following years three daughters were born. Bush resumed his RAM and LLCU duties, and in 1932 accepted a new appointment, as an examiner for the Associated Board of London's Royal Schools of Music, a post which involved extensive overseas travel. These new domestic and professional responsibilities limited Bush's composing activity, but he provided the music for the 1934 Pageant of Labour, organised for the London Trades Council and held at the

Bush's return to composing after the war led to what Richard Stoker, in the ''

Bush's return to composing after the war led to what Richard Stoker, in the ''

Since his youthful ''Last Days of Pompeii'', Bush had not attempted to write opera, but he took up the genre in 1946 with a short operetta for children, ''The Press Gang (or the Escap'd Apprentice)'', for which Nancy supplied the libretto. This was performed by pupils at

Since his youthful ''Last Days of Pompeii'', Bush had not attempted to write opera, but he took up the genre in 1946 with a short operetta for children, ''The Press Gang (or the Escap'd Apprentice)'', for which Nancy supplied the libretto. This was performed by pupils at

During his involvement with opera, Bush continued to compose in other genres. His 1953 cantata ''Voice of the Prophets'', Op. 41, was commissioned by the tenor

During his involvement with opera, Bush continued to compose in other genres. His 1953 cantata ''Voice of the Prophets'', Op. 41, was commissioned by the tenor

In old age, Bush continued to lead an active and productive life, punctuated by periodic commemorations of his life and works. In November 1975 his 50 years' professorship at the RAM was marked in a concert there, and in January 1976 the WMA gave a concert to honour his recent 75th birthday. In 1977 he produced his last major piano work, the ''Twenty-four Preludes'', Op. 84, of which he gave the first performance at the Wigmore Hall on 30 October 1977. A later reviewer described this piece as "music I'd like to have playing beside me as I sprawled on the grass beneath the trees with an ice-cream, watching a county cricket match on a golden afternoon".

In 1978 Bush retired from the RAM after 52 years' service. His 80th birthday in December 1980 was celebrated at concerts in London, Birmingham and East Germany,Craggs, p. 24 and the BBC broadcast a special birthday musical tribute. In the same year he published ''In My Eighth Decade and Other Essays'', in which he stated his personal creed that "as a musician and as a man, Marxism is a guide to action", enabling him to express through music the "struggle to create a condition of social organisation in which science and art will be the possession of all". In 1982 Bush visited the

In old age, Bush continued to lead an active and productive life, punctuated by periodic commemorations of his life and works. In November 1975 his 50 years' professorship at the RAM was marked in a concert there, and in January 1976 the WMA gave a concert to honour his recent 75th birthday. In 1977 he produced his last major piano work, the ''Twenty-four Preludes'', Op. 84, of which he gave the first performance at the Wigmore Hall on 30 October 1977. A later reviewer described this piece as "music I'd like to have playing beside me as I sprawled on the grass beneath the trees with an ice-cream, watching a county cricket match on a golden afternoon".

In 1978 Bush retired from the RAM after 52 years' service. His 80th birthday in December 1980 was celebrated at concerts in London, Birmingham and East Germany,Craggs, p. 24 and the BBC broadcast a special birthday musical tribute. In the same year he published ''In My Eighth Decade and Other Essays'', in which he stated his personal creed that "as a musician and as a man, Marxism is a guide to action", enabling him to express through music the "struggle to create a condition of social organisation in which science and art will be the possession of all". In 1982 Bush visited the

''Alan Bush: A Life''

(1983), documentary directed by Anna Ambrose, British Film Institute

Wat Tyler libretto

A photostat typescript of the Nancy Bush's original libretto

* ttps://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/20050924120000/http://www.bl.uk/collections/bush.html Alan Bush manuscripts in the British Library {{DEFAULTSORT:Bush, Alan 1900 births 1995 deaths 20th-century classical composers 20th-century English composers 20th-century classical pianists 20th-century British male musicians British male pianists English opera composers English male classical composers English classical pianists English communists Male opera composers Male classical pianists Musicians from London Academics of the Royal Academy of Music Alumni of the Royal Academy of Music Fellows of the Royal Academy of Music People educated at Highgate School People from Dulwich Pupils of Artur Schnabel British Army personnel of World War II Royal Army Medical Corps soldiers

Alan Dudley Bush (22 December 1900 – 31 October 1995) was a British composer, pianist, conductor, teacher and political activist. A committed communist, his uncompromising political beliefs were often reflected in his music. He composed prolifically across a range of genres, but struggled through his lifetime for recognition from the British musical establishment, which largely ignored his works.

Bush, from a prosperous middle-class background, enjoyed considerable success as a student at the Royal Academy of Music (RAM) in the early 1920s, and spent much of that decade furthering his compositional and piano-playing skills under distinguished tutors. A two-year period in Berlin in 1929 to 1931, early in the

in the early years of the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

's rise to power, cemented Bush's political convictions and moved him from the mainstream Labour Party to the Communist Party of Great Britain which he joined in 1935. He wrote several large-scale works in the 1930s, and was heavily involved with workers' choirs for whom he composed pageants, choruses and songs. His pro-Soviet stance led to a temporary ban on his music by the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, and his refusal to modify his position in the postwar Cold War era led to a more prolonged semi-ostracism of his music. As a result, the four major operas he wrote between 1950 and 1970 were all premiered in East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

.

In his prewar works, Bush's style retained what commentators have described as an essential Englishness, but was also influenced by the avant-garde European idioms of the inter-war years. During and after the war he began to simplify this style, in line with his Marxism-inspired belief that music should be accessible to the mass of the people. Despite the difficulties he encountered in getting his works performed in the West he continued to compose until well into his eighties. He taught composition at the RAM for more than 50 years, published two books, was the founder and long-time president of the Workers' Music Association, and served as chairman and later vice-president of the Composers' Guild of Great Britain. His contribution to musical life was slowly recognised, in the form of doctorates from two universities and numerous tribute concerts towards the end of his life. Since his death aged 94 in 1995, his musical legacy has been nurtured by the Alan Bush Music Trust, established in 1997.

Life and career

Family background and early life

Bush was born inDulwich

Dulwich (; ) is an area in south London, England. The settlement is mostly in the London Borough of Southwark, with parts in the London Borough of Lambeth, and consists of Dulwich Village, East Dulwich, West Dulwich, and the Southwark half ...

, South London, on 22 December 1900, the third and youngest son of Alfred Walter Bush and Alice Maud, née Brinsley. The Bushes were a prosperous middle-class family, their wealth deriving from the firm of industrial chemists founded by the composer's great-grandfather, W. J. Bush. As a child Alan's health was delicate, and he was initially educated at home. When he was eleven he began at Highgate School as a day pupil, and remained there until 1918. Both of his elder brothers served as officers in the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

; one of them, Alfred junior, was killed on the Western Front in 1917. The other, Hamilton Brinsley Bush, went into the family business and ran twice as Liberal candidate for Watford in the 1950s. The end of the war in November 1918 meant that Alan narrowly avoided being called up for military service; meantime, having determined on a musical career, he had applied to and been accepted by the RAM, where he began his studies in the spring of 1918.

Royal Academy and after

At the RAM, Bush studied composition under Frederick Corder and piano with

At the RAM, Bush studied composition under Frederick Corder and piano with Tobias Matthay

Tobias Augustus Matthay (19 February 185815 December 1945) was an English pianist, teacher, and composer.

Biography

Matthay was born in Clapham, Surrey, in 1858 to parents who had come from northern Germany and eventually became naturalised Brit ...

. He made rapid progress, and won various scholarships and awards, including the Thalberg Scholarship, the Phillimore piano prize, and a Carnegie award for composition. He produced the first compositions of his formal canon: Three Pieces for Two Pianos, Op. 1, and Piano Sonata in B minor, Op. 2, and also made his first attempt to write opera – a scene from Bulwer Lytton's novel ''The Last Days of Pompeii

''The Last Days of Pompeii'' is a novel written by Edward Bulwer-Lytton in 1834. The novel was inspired by the painting ''The Last Day of Pompeii'' by the Russian painter Karl Briullov, which Bulwer-Lytton had seen in Milan. It culminates in ...

'', with a libretto by his brother Brinsley. The work, with Bush at the piano, received a single private performance with family members and friends forming the cast. The manuscript was later destroyed by Bush.

Among Bush's fellow students was Michael Head. The two became friends, as a result of which Bush met Head's 14-year-old sister Nancy. In 1931, ten years after their first meeting, Bush and Nancy would marry and begin a lifelong artistic partnership in which she became Bush's principal librettist, as well as providing the texts for many of his other vocal works.

In 1922 Bush graduated from the RAM, but continued to study composition privately under John Ireland

John Benjamin Ireland (January 30, 1914 – March 21, 1992) was a Canadian actor. He was nominated for an Academy Award for his performance in ''All the King's Men'' (1949), making him the first Vancouver-born actor to receive an Oscar nomin ...

, with whom he formed an enduring friendship. In 1925 Bush was appointed to a teaching post at the RAM, as a professor of harmony and composition, under terms that gave him scope to continue with his studies and to travel. He took further piano study from two pupils of Leschetizky, Benno Moiseiwitsch and Mabel Lander

__NOTOC__

Mabel Lander (1882 – 19 May 1955) was British pianist and teacher, mostly remembered today as piano tutor to the Royal Family in the 1930s and 1940s, though her real legacy comes from her teaching several generations of prominent ...

, from whom he learned the Leschetizky method. In 1926 he made his first of numerous visits to Berlin, where with the violinist Florence Lockwood he gave two concerts of contemporary, mainly British, music which included his own ''Phantasy'' in C minor, Op. 3. The skill of the performers was admired by the critics more than the quality of the music. In 1928 Bush returned to Berlin, to perform with the Brosa Quartet at the Bechstein Hall, in a concert of his own music which included the premieres of the chamber work ''Five Pieces'', Op. 6 and the piano solo ''Relinquishment'', Op. 11. Critical opinion was broadly favourable, the ''Berliner Zeitung am Mittag'' correspondent noting "nothing extravagant but much of promise".

Among the works composed by Bush during this period were the Quartet for piano, violin, viola and cello, Op. 5; Prelude and Fugue for piano, Op. 9; settings of poems by Walter de la Mare

Walter John de la Mare (; 25 April 1873 – 22 June 1956) was an English poet, short story writer, and novelist. He is probably best remembered for his works for children, for his poem "The Listeners", and for a highly acclaimed selection of ...

, Harold Monro

Harold Edward Monro (14 March 1879 – 16 March 1932) was an English poet born in Brussels, Belgium. As the proprietor of the Poetry Bookshop in London, he helped many poets to bring their work before the public.

Life and career

Monro was born ...

and W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

; and his first venture into orchestral music, the Symphonic Impressions of 1926–27, Op. 8. In early 1929 he completed one of his best-known early chamber works, the string quartet ''Dialectic'', Op. 15, which helped to establish Bush's reputation abroad when it was performed at a Prague festival in the 1930s.

Music and politics

Bush had begun to develop an interest in politics during the war years. In 1924, rejecting his parents' conservatism, he joined theIndependent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

(ILP). The following year he joined the London Labour Choral Union (LLCU), a group of largely London-based choirs that had been organised by the socialist composer Rutland Boughton

Rutland Boughton (23 January 187825 January 1960) was an English composer who became well known in the early 20th century as a composer of opera and choral music. He was also an influential communist activist within the Communist Party of Gre ...

, with Labour Party support, to "develop the musical instincts of the people and to render service to the Labour movement". Bush was soon appointed as Boughton's assistant, and two years later, he succeeded Boughton as the LLCU's chief musical adviser, remaining in this post until the body disbanded in 1940.

Through his LLCU work, Bush met Michael Tippett

Sir Michael Kemp Tippett (2 January 1905 – 8 January 1998) was an English composer who rose to prominence during and immediately after the Second World War. In his lifetime he was sometimes ranked with his contemporary Benjamin Britten ...

, five years his junior, who shared Bush's left-wing political perspective. In his memoirs Tippett records his first impressions of Bush: "I learned much from him. His music at the time seemed so adventurous and vigorous".Tippett 1991, pp. 43–44 Tippett's biographer Ian Kemp writes: "Apart from Sibelius, the contemporary composer who taught Tippett as much as anyone else was his own contemporary Alan Bush".

After his 1928 concert tour in Berlin, Bush returned to the city to study piano under

After his 1928 concert tour in Berlin, Bush returned to the city to study piano under Artur Schnabel

Artur Schnabel (17 April 1882 – 15 August 1951) was an Austrian-American classical pianist, composer and pedagogue. Schnabel was known for his intellectual seriousness as a musician, avoiding pure technical bravura. Among the 20th centur ...

.Bullivant, p. 1 He left the ILP in 1929, and joined the Labour Party proper,Craggs, p. viii before taking extended leave from the RAM to begin a two-year course in philosophy and musicology at Berlin's Friedrich-Wilhelm University. Here, his tutors included Max Dessoir

Maximilian Dessoir (8 February 1867 – 19 July 1947) was a German philosopher, psychologist and theorist of aesthetics.

Career

Dessoir was born in Berlin, into a German Jewish family, his parents being Ludwig Dessoir (1810-1874), "Germany's ...

and Friedrich Blume

Friedrich Blume (5 January 1893, in Schlüchtern, Hesse-Nassau – 22 November 1975, in Schlüchtern) was professor of musicology at the University of Kiel from 1938 to 1958. He was a student in Munich, Berlin and Leipzig, and taught in the las ...

. Bush's years in Berlin profoundly affected his political beliefs, and had direct influence on the subsequent character of his music. Michael Jones, writing in ''British Music'' after Bush's death, records Bush's concern at the rise of fascism and antisemitism in Germany. His association with like-minded musicians such as Hanns Eisler

Hanns Eisler (6 July 1898 – 6 September 1962) was an Austrian composer (his father was Austrian, and Eisler fought in a Hungarian regiment in World War I). He is best known for composing the national anthem of East Germany, for his long artisti ...

and Ernst Hermann Meyer, and writers such as Bertold Brecht

Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht (10 February 1898 – 14 August 1956), known professionally as Bertolt Brecht, was a German theatre practitioner, playwright, and poet. Coming of age during the Weimar Republic, he had his first successes as a p ...

, helped to develop his growing political awareness into a lifelong commitment to Marxism and communism. Article reproduced in edited form by the Alan Mush Music Trust Bush's conversion to full-blown communism was not immediate, but in 1935 he finally abandoned Labour and joined the British Communist Party

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was the largest communist organisation in Britain and was founded in 1920 through a merger of several smaller Marxist groups. Many miners joined the CPGB in the 1926 general strike. In 1930, the CPGB ...

.

Notwithstanding the uncompromising nature of his politics, Bush in his writings tended to express his views in restrained terms, "much more like a reforming patrician Whig than a proletarian revolutionary" according to Michael Oliver in a 1995 ''Gramophone'' article. Bush's Grove Music Online biographers also observe that in the politicisation of his music, his folk idioms have more in common with the English traditions of Ralph Vaughan Williams than with the continental radicalism of Kurt Weill.

1930s: emergent composer

In March 1931 Bush and Nancy were married in London, before returning to Germany where Bush continued his studies. In April a BBC broadcast performance of his Dance Overture for Military Band, Op. 12a, received a mixed reception. Nancy Bush quotes two listeners' comments that appeared in the '' Radio Times'' on 8 May 1931. One thought that "such a medley of fearful discords could never be called music", while another opined that " eshould not cry for more Mozart, Haydn or Beethoven if modern composers would all give us sheer beauty like this".N. Bush, p. 38 At the end of summer 1931 the couple returned permanently to England, and settled in the village of Radlett, in Hertfordshire. In the following years three daughters were born. Bush resumed his RAM and LLCU duties, and in 1932 accepted a new appointment, as an examiner for the Associated Board of London's Royal Schools of Music, a post which involved extensive overseas travel. These new domestic and professional responsibilities limited Bush's composing activity, but he provided the music for the 1934 Pageant of Labour, organised for the London Trades Council and held at the

At the end of summer 1931 the couple returned permanently to England, and settled in the village of Radlett, in Hertfordshire. In the following years three daughters were born. Bush resumed his RAM and LLCU duties, and in 1932 accepted a new appointment, as an examiner for the Associated Board of London's Royal Schools of Music, a post which involved extensive overseas travel. These new domestic and professional responsibilities limited Bush's composing activity, but he provided the music for the 1934 Pageant of Labour, organised for the London Trades Council and held at the Crystal Palace

Crystal Palace may refer to:

Places Canada

* Crystal Palace Complex (Dieppe), a former amusement park now a shopping complex in Dieppe, New Brunswick

* Crystal Palace Barracks, London, Ontario

* Crystal Palace (Montreal), an exhibition building ...

during October. Tippett, who co-conducted the event, later described it as a "high water mark" in Bush's drive to provide workers' choirs with settings for left-wing texts. In 1936 Bush was one of the founders of the Workers' Musical Association (WMA), and became its first chairman.

In 1935 Bush began work on a piano concerto which, completed in 1937, included the unusual feature of a mixed chorus and baritone soloist in the finale, singing a radical text by Randall Swingler

Randall Carline Swingler MM (28 May 1909 – 19 June 1967) was an English poet, writing extensively in the 1930s in the communist interest.

Early life and education

His was a prosperous upper middle class Anglican family in Aldershot, with an ...

. Bush played the piano part when the work was premiered by the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Sir Adrian Boult

Sir Adrian Cedric Boult, CH (; 8 April 1889 – 22 February 1983) was an English conductor. Brought up in a prosperous mercantile family, he followed musical studies in England and at Leipzig, Germany, with early conducting work in London ...

on 4 March 1938. The largely left-wing audience responded to the work enthusiastically;Hall, p. 133 Tippett observed that "to counter the radical tendencies of the finale ... Boult forced the applause to end by unexpectedly performing the National Anthem". A performance of the concerto a year later, at the 1939 "Festival of Music for the People", drew caustic comments from Neville Cardus

Sir John Frederick Neville Cardus, Commander of the Order of the British Empire, CBE (2 April 188828 February 1975) was an English writer and critic. From an impoverished home background, and mainly self-educated, he became ''The Manchester Gua ...

in ''The Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

''. Cardus saw little direction and no humour in the music: "Why don't these people laugh at themselves now and then? Just for fun."

Bush provided much of the music, and also acted as general director, for the London Co-operative Societies' pageant "Towards Tomorrow", held at Wembley Stadium

Wembley Stadium (branded as Wembley Stadium connected by EE for sponsorship reasons) is a football stadium in Wembley, London. It opened in 2007 on the site of the original Wembley Stadium, which was demolished from 2002 to 2003. The stadium ...

on 2 July 1938. In the autumn of that year he visited both the Soviet Union and the United States.Craggs, p. 18 Back home in early 1939 he was closely involved in founding and conducting the London String Orchestra, which operated successfully until 1941 and again in the immediate postwar years. He also began to write a major orchestral work, his Symphony No. 1 in C. Amid this busy life Bush was elected a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Music.

Second World War

When war broke out in September 1939, Bush registered for military service under the National Service (Armed Forces) Act of 1939. He was not called up immediately, and continued his musical life, helping to form the WMA Singers to replace the now-defunct LLCU, and founding the William Morris Music Society. In April 1940 he conducted aQueen's Hall

The Queen's Hall was a concert hall in Langham Place, London, Langham Place, London, opened in 1893. Designed by the architect Thomas Knightley, it had room for an audience of about 2,500 people. It became London's principal concert venue. Fro ...

concert of music by Soviet composers which included the British premieres of Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, , group=n (9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony in 1926 and was regarded throughout his life as a major compo ...

's Fifth Symphony, and Khatchaturian's Piano Concerto. William Glock

Sir William Frederick Glock, CBE (3 May 190828 June 2000) was a British music critic and musical administrator who was instrumental in introducing the Continental avant-garde, notably promoting the career of Pierre Boulez.

Biography

Glock was bo ...

in ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the ...

'' was disdainful, dismissing the Khatachurian concerto as "sixth-rate", and criticising the inordinate length, as he saw it, of the symphony.

Bush was among many musicians, artists and writers who in January 1941 signed up to the communist-led People's Convention, which promoted a six-point radical anti-war programme that included friendship with the Soviet Union and "a people's peace". The BBC advised him that because of his association with this movement, he and his music would no longer be broadcast. This action drew strong protests from, among others, E. M. Forster

Edward Morgan Forster (1 January 1879 – 7 June 1970) was an English author, best known for his novels, particularly ''A Room with a View'' (1908), ''Howards End'' (1910), and ''A Passage to India'' (1924). He also wrote numerous short stori ...

and Ralph Vaughan Williams.Lucas, p. 160 The ban was opposed by the prime minister, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

, and proved short-lived; it was annulled following the German invasion of the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

in June 1941.Craggs, p. ix

In November 1941 Bush was conscripted into the army, and after initial training was assigned to the Royal Army Medical Corps. Based in London, he was given leave to perform in concerts, which enabled him to conduct the premiere of his First Symphony at a BBC Promenade Concert in the Royal Albert Hall on 24 July 1942. He also performed regularly with the London String Orchestra, and in 1944 was the piano soloist in the British premiere of Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, , group=n (9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony in 1926 and was regarded throughout his life as a major compo ...

's Piano Quintet. His wartime compositions were few; among them were the "Festal Day" Overture, Op. 23, written for Vaughan Williams's 70th birthday in 1942, and several songs and choruses including "Freedom on the March", written for a British-Soviet Unity Demonstration at the Albert Hall on 27 June 1943.

Bush's relatively calm war was marred by the death, in 1944, of his seven-year-old daughter Alice in a road accident. As the war in Europe drew to its end, Bush was posted to the Far East despite being well over the normal age limit for overseas service. The matter was raised in Parliament by the Independent Labour member D. N. Pritt, who enquired whether political factors were behind the decision. The posting was withdrawn; and Bush remained in London until his discharge in December 1945.

Post-war: struggle for recognition and performance

Persona non grata

Bush's return to composing after the war led to what Richard Stoker, in the ''

Bush's return to composing after the war led to what Richard Stoker, in the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'', calls "his best period". However, Bush's attempts to secure a place in the concert repertoire were frustrated. A contributory factor may have been what the critic Dominic Daula calls Bush's "intriguingly unique compositional voice" that challenged critics and audiences alike. But the composer's refusal to modify his pro-Soviet stance following the onset of the Cold War alienated both the public and the music establishment, a factor which Bush acknowledged 20 years later: "People who were in a position to promote my works were afraid to do so. They were afraid of being labelled". Stoker comments that "in a less tolerant country he would certainly have been imprisoned, or worse. But he was merely ignored, both politically, and, which is a pity, as a composer". Nancy Bush writes that the BBC considered him ''persona non grata'', and imposed an almost complete though unofficial broadcast ban that lasted for some 15 years after the war.

As well as resuming his teaching routines, Bush embarked on a busy schedule of travel, mainly in Eastern Europe with the WMA choir. While in Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

in August 1947, he and the WMA performed his unaccompanied chorus ''Lidice'' at the site of the village of that name, which had been destroyed by the Nazis in 1942 in a reprisal for the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich ( ; ; 7 March 1904 – 4 June 1942) was a high-ranking German SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust.

He was chief of the Reich Security Main Office (inclu ...

.

Among Bush's earliest postwar works was the ''English Suite'', performed by the revived London String Orchestra at the Wigmore Hall

Wigmore Hall is a concert hall located at 36 Wigmore Street, London. Originally called Bechstein Hall, it specialises in performances of chamber music, early music, vocal music and song recitals. It is widely regarded as one of the world's leadi ...

on 9 February 1946.Foreman, p. 155 The orchestra had suspended its operations in 1941; after the war, Bush's failure to secure funding for it led to its closure, despite considerable artistic success. Critics noted in the work a change of idiom, away from the European avant-garde character of much of his prewar music and towards a simpler popular style. This change was acknowledged by Bush as he responded to the 1948 decree issued by Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

's director of cultural policy, Andrei Zhdanov

Andrei Aleksandrovich Zhdanov ( rus, Андре́й Алекса́ндрович Жда́нов, p=ɐnˈdrej ɐlʲɪˈksandrəvʲɪtɕ ˈʐdanəf, links=yes; – 31 August 1948) was a Soviet politician and cultural ideologist. After World War ...

, against formalism

Formalism may refer to:

* Form (disambiguation)

* Formal (disambiguation)

* Legal formalism, legal positivist view that the substantive justice of a law is a question for the legislature rather than the judiciary

* Formalism (linguistics)

* Scie ...

and dissonance in modern music – although the process of simplification had probably begun during the war years.

In 1948 Bush accepted a commission from the Nottingham Co-operative Society to write a symphony as part of the city's quincentennial celebrations in 1949. According to Foreman, "by any standards this is one of Bush's most approachable scores",Foreman, p. 119 yet since its Nottingham premiere on 27 June 1949 and its London debut on 11 December 1952 under Boult and the London Philharmonic, the work has been rarely heard in Britain. His Violin Concerto, Op. 32, received its premiere on 25 August 1949, with Max Rostal

Max Rostal (7 July 1905 – 6 August 1991) was a violinist and a viola player. He was Austrian-born, but later took British citizenship.

Biography

Max Rostal was born in Cieszyn to a Jewish merchant family. As a child prodigy, he started studyin ...

as soloist. In this work Bush explained that "the soloist represents the individual, the orchestra world society, and the work epresentsthe individual's struggles and of his final absorption into society". ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was f ...

''s critic observed that "it was the orchestra, i.e. society, that after a strenuous opening gave up the struggle".

In 1947 Bush became chairman of the Composers' Guild of Great Britain for 1947–48. He also produced a full-length textbook, ''Strict Counterpoint in the Palestrina Style'' (Joseph Williams, London, 1948). On 15 December 1950 the WMA marked Bush's 50th birthday with a special concert of his music at the Conway Hall

The Conway Hall Ethical Society, formerly the South Place Ethical Society, based in London at Conway Hall, is thought to be the oldest surviving freethought organisation in the world and is the only remaining ethical society in the United Kin ...

.

Opera ventures

Since his youthful ''Last Days of Pompeii'', Bush had not attempted to write opera, but he took up the genre in 1946 with a short operetta for children, ''The Press Gang (or the Escap'd Apprentice)'', for which Nancy supplied the libretto. This was performed by pupils at

Since his youthful ''Last Days of Pompeii'', Bush had not attempted to write opera, but he took up the genre in 1946 with a short operetta for children, ''The Press Gang (or the Escap'd Apprentice)'', for which Nancy supplied the libretto. This was performed by pupils at St Christopher School, Letchworth

St Christopher School is a boarding and day co-educational independent school in Letchworth Garden City, Hertfordshire, England.

Established in 1915, shortly after Ebenezer Howard founded Letchworth Garden City, the school is a long-time prop ...

, on 7 March 1947. The following year he began a more ambitious venture, a full-length grand opera recounting the story of Wat Tyler

Wat Tyler (c. 1320/4 January 1341 – 15 June 1381) was a leader of the 1381 Peasants' Revolt in England. He led a group of rebels from Canterbury to London to oppose the institution of a poll tax and to demand economic and social reforms. Wh ...

, who led the Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, also named Wat Tyler's Rebellion or the Great Rising, was a major uprising across large parts of England in 1381. The revolt had various causes, including the socio-economic and political tensions generated by the Blac ...

of 1381. ''Wat Tyler'', again to Nancy's libretto, was submitted in 1950 to the Arts Council's Festival of Britain

The Festival of Britain was a national exhibition and fair that reached millions of visitors throughout the United Kingdom in the summer of 1951. Historian Kenneth O. Morgan says the Festival was a "triumphant success" during which people:

...

opera competition, and was one of four prizewinners – Bush received £400. The opera was not taken up by any of the British opera houses, and was first staged at Leipzig Opera

The Leipzig Opera (in German: ) is an opera house and opera company located at the Augustusplatz and the Inner City Ring Road at its east side in Leipzig's district Mitte, Germany.

History

Performances of opera in Leipzig trace back to Sing ...

in 1953. It was well received, retained for the season and ran again in the following year; there was a further performance in Rostock in 1955. ''Wat Tyler'' did not receive its full British premiere until 19 June 1974, when it was produced at Sadler's Wells

Sadler's Wells Theatre is a performing arts venue in Clerkenwell, London, England located on Rosebery Avenue next to New River Head. The present-day theatre is the sixth on the site since 1683. It consists of two performance spaces: a 1,500-seat ...

; as of 2017, this remains the only professional staging of a Bush opera in Britain.

Bush's second opera, ''Men of Blackmoor'', composed in 1954–55 to Nancy's libretto, is a story of Northumbrian miners in the early 19th century; Bush went down a mine as part of his research. It received its premiere at the German National Theatre, Weimar on 18 November 1956. Like ''Wat Tyler'' in Leipzig, the opera was successful; after the Weimar season there were further East German productions in Jena

Jena () is a German city and the second largest city in Thuringia. Together with the nearby cities of Erfurt and Weimar, it forms the central metropolitan area of Thuringia with approximately 500,000 inhabitants, while the city itself has a po ...

(1957), Leipzig (1959) and Zwickau

Zwickau (; is, with around 87,500 inhabitants (2020), the fourth-largest city of Saxony after Leipzig, Dresden and Chemnitz and it is the seat of the Zwickau District. The West Saxon city is situated in the valley of the Zwickau Mulde (German: ...

(1960). In Britain there were student performances at Oxford in 1960, and Bristol in 1974. In December 1960 David Drew in the ''New Statesman'' wrote: "The chief virtue of ''Men of Blackmoor'', and the reason why it particularly deserves a rofessionalperformance at this historical point, is its unfailing honesty ... it is never cheap, and at its best achieves a genuine dignity."

For his third opera, Bush chose a contemporary theme – the struggle against colonial rule. He intended to collect appropriate musical material from British Guiana, but an attempt to visit the colony in 1957 was thwarted when its government refused him entry. The ban was rescinded the following year, and in 1959 Bush was able to gather and record a great deal of authentic music from the local African and Indian populations. The eventual result was ''The Sugar Reapers'', premiered at Leipzig on 11 December 1966. ''The Times'' correspondent, praising the performance, wrote: "One can only hope that London will soon see a production of its own". With Nancy, Bush wrote two more operettas for children: ''The Spell Unbound'' (1953) and ''The Ferryman's Daughter'' (1961). His final opera, written in 1965–67, was '' Joe Hill'', based on the life story of Joe Hill, an American union activist and songwriter who was controversially convicted of murder and executed in 1915. The opera, to a libretto by Barrie Stavis, was premiered at the German Berlin State Opera

The (), also known as the Berlin State Opera (german: Staatsoper Berlin), is a listed building on Unter den Linden boulevard in the historic center of Berlin, Germany. The opera house was built by order of Prussian king Frederick the Great from ...

on 29 September 1970, and in 1979 was broadcast by the BBC.

1953–1975

During his involvement with opera, Bush continued to compose in other genres. His 1953 cantata ''Voice of the Prophets'', Op. 41, was commissioned by the tenor

During his involvement with opera, Bush continued to compose in other genres. His 1953 cantata ''Voice of the Prophets'', Op. 41, was commissioned by the tenor Peter Pears

Sir Peter Neville Luard Pears ( ; 22 June 19103 April 1986) was an English tenor. His career was closely associated with the composer Benjamin Britten, his personal and professional partner for nearly forty years.

Pears' musical career starte ...

and sung by Pears at its premiere on 22 May 1953. In 1959–60 he produced two major orchestral works: the ''Dorian Passacaglia and Fugue'', Op. 52, and the Third Symphony, Op. 53, known as the "Byron" since it depicts musically scenes from the life of the poet. The symphony, a commission from East German Radio, was first performed at Leipzig on 20 March 1962. Colin Mason, writing in ''The Guardian'', thought the work had a stronger socialist programme than the Nottingham symphony of 1949. The ending of the second movement, a long tune representing Byron's speech against the extension of the death penalty was, Mason wrote, "a splendid piece". The symphony was awarded that year's Händel Prize in the city of Halle.Craggs, p. 22

At the end of the 1960s Bush wrote, among other works, ''Time Remembered'', Op. 67, for chamber orchestra, and ''Scherzo for Wind Orchestra and Percussion'', Op. 68, based on an original Guyanese theme. In 1969 he produced the first of three song cycles, ''The Freight of Harvest'', Op. 69 – ''Life's Span'' and ''Woman's Life'' would follow in 1974 and 1977. In the 1970s, while maintaining his teaching commitment to the RAM, he continued to perform in the concert hall as conductor and pianist. Bush was slowly being recognised for his achievements, even by those who had long cold-shouldered him. In 1968 he was awarded a Doctor of Music

The Doctor of Music degree (D.Mus., D.M., Mus.D. or occasionally Mus.Doc.) is a higher doctorate awarded on the basis of a substantial portfolio of compositions and/or scholarly publications on music. Like other higher doctorates, it is granted b ...

degree by the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

, and two years later received an honorary doctorate from the University of Durham

Durham University (legally the University of Durham) is a collegiate university, collegiate public university, public research university in Durham, England, Durham, England, founded by an Act of Parliament in 1832 and incorporated by royal charte ...

. On 6 December 1970, just before Bush's 70th birthday, BBC Television broadcast a programme about his life and works, and on 16 February 1971 the RAM hosted a special (late) birthday concert, in which he and Pears performed songs from ''Voices of the Prophets''. Bush featured in a further television programme, broadcast on 25 October 1975, in a series entitled "Born in 1900".

Final years

In old age, Bush continued to lead an active and productive life, punctuated by periodic commemorations of his life and works. In November 1975 his 50 years' professorship at the RAM was marked in a concert there, and in January 1976 the WMA gave a concert to honour his recent 75th birthday. In 1977 he produced his last major piano work, the ''Twenty-four Preludes'', Op. 84, of which he gave the first performance at the Wigmore Hall on 30 October 1977. A later reviewer described this piece as "music I'd like to have playing beside me as I sprawled on the grass beneath the trees with an ice-cream, watching a county cricket match on a golden afternoon".

In 1978 Bush retired from the RAM after 52 years' service. His 80th birthday in December 1980 was celebrated at concerts in London, Birmingham and East Germany,Craggs, p. 24 and the BBC broadcast a special birthday musical tribute. In the same year he published ''In My Eighth Decade and Other Essays'', in which he stated his personal creed that "as a musician and as a man, Marxism is a guide to action", enabling him to express through music the "struggle to create a condition of social organisation in which science and art will be the possession of all". In 1982 Bush visited the

In old age, Bush continued to lead an active and productive life, punctuated by periodic commemorations of his life and works. In November 1975 his 50 years' professorship at the RAM was marked in a concert there, and in January 1976 the WMA gave a concert to honour his recent 75th birthday. In 1977 he produced his last major piano work, the ''Twenty-four Preludes'', Op. 84, of which he gave the first performance at the Wigmore Hall on 30 October 1977. A later reviewer described this piece as "music I'd like to have playing beside me as I sprawled on the grass beneath the trees with an ice-cream, watching a county cricket match on a golden afternoon".

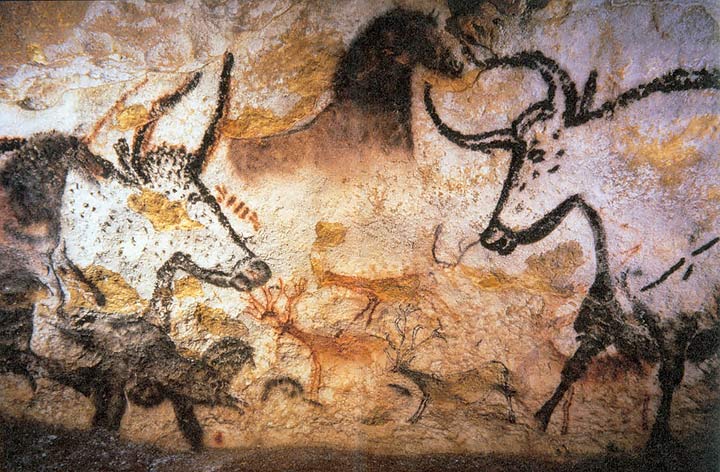

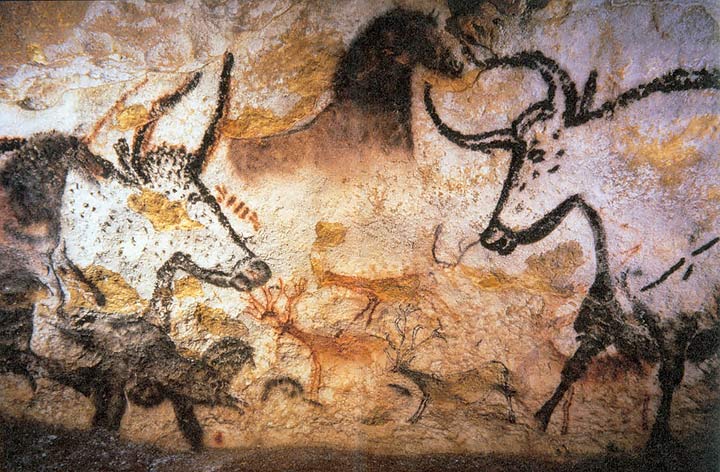

In 1978 Bush retired from the RAM after 52 years' service. His 80th birthday in December 1980 was celebrated at concerts in London, Birmingham and East Germany,Craggs, p. 24 and the BBC broadcast a special birthday musical tribute. In the same year he published ''In My Eighth Decade and Other Essays'', in which he stated his personal creed that "as a musician and as a man, Marxism is a guide to action", enabling him to express through music the "struggle to create a condition of social organisation in which science and art will be the possession of all". In 1982 Bush visited the Lascaux

Lascaux ( , ; french: Grotte de Lascaux , "Lascaux Cave") is a network of caves near the village of Montignac, in the department of Dordogne in southwestern France. Over 600 parietal wall paintings cover the interior walls and ceilings of ...

caves in south-western France, and was inspired by the prehistoric cave paintings to write his fourth and final symphony, Op. 94, subtitled the "Lascaux".Foreman, pp. 133–34 This, his last major orchestral work, was premiered by the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra

The BBC Philharmonic is a national British broadcasting symphony orchestra and is one of five radio orchestras maintained by the British Broadcasting Corporation. The Philharmonic is a department of the BBC North Group division based at Media ...

, under Edward Downes

Sir Edward Thomas ("Ted") Downes, CBE (17 June 1924 – 10 July 2009) was an English conductor, specialising in opera.

He was associated with the Royal Opera House from 1952, and with Opera Australia from 1970. He was also well known for hi ...

in Manchester, on 25 March 1986.

In the late 1980s Bush was increasingly hampered by failing eyesight. His last formal compositions appeared in 1988: "Spring Woodland and Summer Garden" for solo piano, Op. 124, and ''Summer Valley'' for cello and piano, Op. 125, although he continued to compose privately and play the piano. Nancy's health meanwhile deteriorated, and she died on 12 October 1991. Bush lived on quietly at Radlett for another four years, able to recall the events of his youth but with no memory of the last fifty years and unaware of the collapse of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

in 1991. He died in Watford General hospital on 31 October 1995, after a short illness, at the age of 94.

Music

General character

Despite undergoing various changes of emphasis, Bush's music retained a voice distinct from that of any of his contemporaries. One critic describes the typical Bush sound as "Mild dominant discords, of consonant effect, used with great originality in uncommon progressions alive with swift, purposeful harmonic movement ... except in enjaminBritten they are nowhere used with more telling expression, colour and sense of movement than in Bush". John Ireland, Bush's early mentor, instilled "the sophisticated and restrained craftsmanship which marked Bush's music from the beginning", introducing him to folksong andPalestrina

Palestrina (ancient ''Praeneste''; grc, Πραίνεστος, ''Prainestos'') is a modern Italian city and ''comune'' (municipality) with a population of about 22,000, in Lazio, about east of Rome. It is connected to the latter by the Via Pre ...

, both important building blocks in the development of Bush's mature style. Daula comments that "Bush's music does not erelyimitate the sound-world of his Renaissance predecessors", but creates his unique fingerprint by " uxtaposing16th century modal counterpoint with late- and post-romantic harmony".

Bush's music, at least from the mid-1930s, often carried political overtones. His obituarist Rupert Christiansen writes that, as a principled Marxist, Bush "put the requirements of the revolutionary proletariat at the head of the composer's responsibilities", a choice which others, such as Tippett, chose not to make. However, Vaughan Williams thought that, despite Bush's oft-declared theories of the purposes of art and music, "when the inspiration comes over him he forgets all about this and remembers only the one eternal rule for all artists, 'To thine own self be true'."Hall, p. 132

To 1945

According to Duncan Hall's account of the music culture of the Labour Movement in the inter-war years, Bush's youthful music, composed before his Berlin sojourn, already demonstrated its essential character. His ''Dialectic for String Quartet'' (1929), Op. 15, created a strong impression when first heard in 1935, as "a musical discourse of driving intensity and virile incident". Christiansen highlights its "tightness and austerity" in contrast to the more fashionable lyricism then prevalent in English music. Bush's years in Berlin brought into his music the advanced Central European idioms that characterise his major orchestral compositions of the period: the Piano Concerto (1935–37), and the First Symphony (1939–40). Nancy Bush describes the Piano Concerto as Bush's first attempt to fuse his musical and political ideas. The symphony was even more overtly political, representing in its three movements greed (of the bourgeoisie), frustration (of the proletariat) and the final liberation of the latter, but not, according to Christiansen, "in an idiom calculated to appeal to the masses". Aside from these large-scale works, much of Bush's compositional activity in the 1930s was devoted to pageants, songs and choruses written for his choirs, work undertaken with the utmost seriousness. In his introduction to a 1938 socialist song book, Bush wrote that "socialists must sing what we mean and sing it like we mean it".Hall, p. 134 Under Bush's influence the "music of the workers" moved from the high aesthetic represented by, for example, Arthur Bourchier's mid-1920s pamphlet ''Art and Culture in Relation to Socialism'', towards an expression with broader popular appeal.Postwar and beyond

Although Bush accepted Zhdanov's 1948 diktat without demur and acted accordingly, his postwar simplifications had begun earlier and would continue as part of a gradual process. Bush first outlined the basis of his new method of composition in an article, "The Crisis of Modern Music", which appeared in WMA's ''Keynote'' magazine in spring 1946. The method, in which every note has thematic significance, has drawn comparison by critics with Schoenberg's twelve-note system, although Bush rejected this equation. Many of Bush's best-known works were written in the immediate postwar years.Anthony Payne

Anthony Edward Payne (2 August 1936 – 30 April 2021) was an English composer, music critic and musicologist. He is best known for his acclaimed completion of Edward Elgar's third symphony, which subsequently gained wide acceptance into Elga ...

described the ''Three Concert Studies for Piano Trio'' (Op. 31) of 1947 as exceeding Britten in its inventiveness, "a high-water mark in Bush's mature art". The Violin Concerto (Op. 32, 1948) has been cited as "a work as beautiful and refined as any in the genre since Walton's". Foreman considers the concerto, which uses twelve-tone themes, to be the epitome of Bush's thematic theory of composition, although Bush's contemporary, Edmund Rubbra

Edmund Rubbra (; 23 May 190114 February 1986) was a British composer. He composed both instrumental and vocal works for soloists, chamber groups and full choruses and orchestras. He was greatly esteemed by fellow musicians and was at the peak o ...

, thought it too intellectual for general audiences. The ''Dorian Passacaglia and Fugue'' for timpani, percussion and strings, (Op. 52, 1959), involves eight variations in the Dorian mode

Dorian mode or Doric mode can refer to three very different but interrelated subjects: one of the Ancient Greek ''harmoniai'' (characteristic melodic behaviour, or the scale structure associated with it); one of the medieval musical modes; or—mo ...

, followed by eight in other modes culminating in a final quadruple fugue in six parts. ''Musical Opinion''s critic praised the composer's "wonderful control and splendid craftsmanship" in this piece, and predicted that it could become the most popular of all Bush's orchestral works.

The postwar period also saw the beginning of Bush's 20-year involvement with grand opera, a genre in which, although he achieved little commercial recognition, he was retrospectively hailed by critics as a master of British opera second only to Britten. His first venture, ''Wat Tyler'', was written in a form which Bush thought acceptable to the general British public;Foreman, pp. 122–23 it was not his choice, he wrote, that the opera and its successors all found their initial audiences in East Germany. When eventually staged in Britain in 1974 the opera, although well received at Sadler's Wells, seemed somewhat old-fashioned; Philip Hope-Wallace in ''The Guardian'' thought the ending degenerated into "a choral union cantata", and found the music pleasant but not especially memorable. Bush's three other major operas were all characterised by their use of "local" music: Northumbrian folk-song in the case of ''Men of Blackmoor'', Guyanese songs and dances in ''The Sugar Reapers'', and American folk music in ''Joe Hill'' – the last-named used in a manner reminiscent of Kurt Weill and the German opera with which Bush had become familiar in the early 1930s.

The extent to which Bush's music changed substantially after the war was addressed by Meirion Bowen, reviewing a Bush concert in the 1980s. Bowen noted a distinct contrast between early and late works, the former showing primarily the influences of Ireland and of Bush's European contacts, while in the later pieces the idiom was "often overtly folklike and Vaughan Williams-ish". In general Bush's late works continued to show all the hallmarks of his postwar oeuvre: vigour, clarity of tone and masterful use of counterpoint. The Lascaux symphony, written when he was 83, is the composer's final major orchestral statement, and addresses deep philosophical issues relating to the origins and destiny of mankind.

Assessment

In the 1920s it appeared that Bush might emerge as Britain's foremost pianist, after his studies under the leading teachers of the day, but he turned to composition as his principal musical activity. In Foreman's summary he is "a major figure who really straddles the century as almost no other composer does". He remained a pianist of consequence, with a strong and reliable, if heavy, touch. Joanna Bullivant, writing in ''Music and Letters'', maintains that in his music Bush subordinated all ideas of personal expression to the ideology of Marxism. The critic Hugo Cole thought that, as a composer, Bush came close toPaul Hindemith

Paul Hindemith (; 16 November 189528 December 1963) was a German composer, music theorist, teacher, violist and conductor. He founded the Amar Quartet in 1921, touring extensively in Europe. As a composer, he became a major advocate of the ' ...

's ideal: "one for whom music is felt as a moral and social force, and only incidentally as a means of personal expression". The composer Wilfrid Mellers

Wilfrid Howard Mellers (26 April 1914 – 17 May 2008) was an English music critic, musicologist and composer.

Early life

Born in Leamington, Warwickshire, Mellers was educated at the local Leamington College and later won a scholarship to Dow ...

credits Bush with more than ideological correctness; while remaining faithful to his creed even when it was entirely out of fashion, he "attempt dto re-establish an English tradition meaningful to his country's past, present and future". Hall describes Bush as "a key figure in the democratisation of art in Britain, achieving far more in this regard than his pedagogic, utopian patrons and peers, the labour romantics."

The music critic Colin Mason described Bush's music thus:His range is wide, the quality of his music consistently excellent. He has the intellectual concentration of Tippett, the easy command and expansiveness of Walton, the nervous intensity of Rawsthorne, the serene leisureliness of Rubbra ... He is surpassed only in melody, as are the others, by Walton, but not even by him in harmonic richness, nor by Tippett in contrapuntal originality and the expressive power of rather austere musical thought, nor by Rawsthorne in concise, compelling utterance and telling invention, nor by Rubbra in handling large forms well.

Legacy

Bush's long career as a teacher influenced generations of English composers and performers. Tippett was never a formal pupil, but he acknowledged a deep debt to Bush. Herbert Murrill, a pupil of Bush's at the RAM in the 1920s, wrote in 1950 of his tutor: " ere is humility in his makeup, and I believe that no man can achieve greatness in the arts without humility ... To Alan Bush I owe much, not least the artistic strength and right to differ from him". Among postwar Bush students are the composers Timothy Bowers,Edward Gregson

Edward Gregson (born 23 July 1945) is an English composer of instrumental and choral music, particularly for brass and wind bands and ensembles, as well as music for the theatre, film, and television. He was also principal of the Royal Northern ...

, David Gow, Roger Steptoe, E. Florence Whitlock, and Michael Nyman, and the pianists John Bingham

John Armor Bingham (January 21, 1815 – March 19, 1900) was an American politician who served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican representative from Ohio and as the United States ambassador to Japan. In his time as a congress ...

and Graham Johnson. Through his sponsorship of the London String Quartet Bush helped launch the careers of string players such as Norbert Brainin

Norbert Brainin, OBE (12 March 1923 in Vienna – 10 April 2005 in London) was the first violinist of the Amadeus Quartet, one of the world's most highly regarded string quartets.

Because of Brainin's Jewish origin, he was driven out of Vie ...

and Emanuel Hurwitz

Emanuel Hurwitz (7 May 1919 – 19 November 2006) was a British violinist. He was born in London to parents of Russian-Jewish ancestry.

He started playing the violin when he was five years old, and took up a scholarship at the Royal Academy of ...

, both of whom later achieved international recognition.

Bush's music was under-represented in the concert repertoire in his lifetime, and virtually disappeared after his death. The 2000 centenary of his birth was markedly low key; the Prom season ignored him, although there was a memorial concert at the Wigmore Hall on 1 November, and a BBC broadcast of the Piano Concerto on 19 December. The centenary, albeit quietly observed, helped to introduce the name and music of Bush to a new generation of music lovers, and generated an increase in both performance and recordings. The centenary also heralded an awakening of scholarly interest in Bush, whose life and works were the subject of numerous PhD theses in the early 20th century. Scholars such as Paul Harper-Scott and Joanna Bullivant have obtained access to new material, including documents released since the collapse of the Soviet Union, and Bush's MI5 file. This, says Bullivant, enables a more informed assessment of the interrelationships within Bush's music and his communism, and of the inherent conflicting priorities.

In October 1997 family members and friends founded The Alan Bush Music Trust "to promote the education and appreciation by the public in and of music and, in particular, the works of the British composer Alan Bush".Craggs, p. 25 The trust provides a newsletter, features news stories, promotes performances and recordings of Bush's works, and through its website reproduces wide-ranging critical and biographical material.

It continues to monitor concert performances of Bush's works, and other Bush-related events, at home and abroad.

At the time of Bush's centenary, Martin Anderson, writing in the British Music Information Centre's newsletter, summarised Bush's compositional career:

Bush was not a natural melodist à la Dvorák, though he could produce an appealing tune when he set his mind to it. But he was a first-rate contrapuntist, and his harmonic world can glow with a rare internal warmth. It would be foolish to claim that everything he wrote was a masterpiece – and equally idiotic to turn our backs on the many outstanding scores still awaiting assiduous attention.

Recordings

Before Bush's centenary year, 2000, the few available recordings of his music included none of the major works. In the 21st century much has been added, including recordings of Symphonies 1, 2 and 4, the Piano and Violin Concertos, many of the main vocal works, the Twenty-Four Preludes, and the complete organ works.Notes and references

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

''Alan Bush: A Life''

(1983), documentary directed by Anna Ambrose, British Film Institute

Wat Tyler libretto

A photostat typescript of the Nancy Bush's original libretto

* ttps://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/20050924120000/http://www.bl.uk/collections/bush.html Alan Bush manuscripts in the British Library {{DEFAULTSORT:Bush, Alan 1900 births 1995 deaths 20th-century classical composers 20th-century English composers 20th-century classical pianists 20th-century British male musicians British male pianists English opera composers English male classical composers English classical pianists English communists Male opera composers Male classical pianists Musicians from London Academics of the Royal Academy of Music Alumni of the Royal Academy of Music Fellows of the Royal Academy of Music People educated at Highgate School People from Dulwich Pupils of Artur Schnabel British Army personnel of World War II Royal Army Medical Corps soldiers