Alamanno da Costa on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alamanno da Costa (active 1193–1224, died before 1229) was a Genoese admiral. He became the count of

In 1216, Alamanno assisted Enrico in an attempt to conquer

In 1216, Alamanno assisted Enrico in an attempt to conquer

Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

*Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

*Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

**North Syracuse, New York

*Syracuse, Indiana

* Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, Miss ...

in the Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily ( la, Regnum Siciliae; it, Regno di Sicilia; scn, Regnu di Sicilia) was a state that existed in the south of the Italian Peninsula and for a time the region of Ifriqiya from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 un ...

, and led naval expeditions throughout the eastern Mediterranean. He was an important figure in Genoa's longstanding conflict with Pisa

Pisa ( , or ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for its leaning tower, the cit ...

and in the origin of its conflict with Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

. The historian Ernst Kantorowicz

Ernst Hartwig Kantorowicz (May 3, 1895 – September 9, 1963) was a German historian of medieval political and intellectual history and art, known for his 1927 book '' Kaiser Friedrich der Zweite'' on Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, and ''The Kin ...

called him a "famous prince of pirates".

Early free-lance career

Alamanno came from Genoa's mercantile class, and the earliest record of him dates from 1193, when he joined an ''accomende'', a commercial partnership, directed towards Sicily. In 1204, Alamanno and his son Benvenuto, on their own initiative, set out aboard the ''Carroccia'' in search of the Pisan corsair ''Leopardo''. The ''Carroccia'' and ''Leopardo'' were both classed as ''navi''—broad-beamed, lateen-rigged ships. The former had on board 500 armed men, and the latter probably half as many. The inventory taken after Alamanno successfully captured the ''Leopardo'' and integrated her into his force lists 280 suits of armour among the booty. Presumably this represents the number of marines she carried. In 1162 theEmperor Frederick I

Frederick Barbarossa (December 1122 – 10 June 1190), also known as Frederick I (german: link=no, Friedrich I, it, Federico I), was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 until his death 35 years later. He was elected King of Germany in Frankfurt on ...

signed a treaty with the Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( lij, Repúbrica de Zêna ; it, Repubblica di Genova; la, Res Publica Ianuensis) was a medieval and early modern maritime republic from the 11th century to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italian coast. During the Lat ...

, offering it the city of Syracuse with its countryside as far as Noto

Noto ( scn, Notu; la, Netum) is a city and in the Province of Syracuse, Sicily, Italy. It is southwest of the city of Syracuse at the foot of the Iblean Mountains. It lends its name to the surrounding area Val di Noto. In 2002 Noto and i ...

if they would provide naval assistance against the Kingdom of Sicily. In 1194, his son, the Emperor Henry VI

Henry VI (German: ''Heinrich VI.''; November 1165 – 28 September 1197), a member of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, was King of Germany (King of the Romans) from 1169 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1191 until his death. From 1194 he was also King of Sic ...

, confirmed the treaty and with Genoese help took Syracuse in his conquest of Sicily. He refused to honour the treaty and, because they supported the vicar of Sicily, Markward von Anweiler

Markward von Annweiler (died 1202) was Imperial Seneschal and Regent of the Kingdom of Sicily.

Biography

Markward was a ministerialis, that is, he came not from the free nobility, but from a class of unfree knights and administrators whose purp ...

, in 1202 the Pisans, under Count Ranieri di Manenta, took possession of it. It was not until 1204, seven years after Henry's death, that Genoa took possession of the city. Leading a Genoese fleet towards Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

, Alamanno changed course at Malta and, in agreement with Enrico Pescatore Henry, known as Enrico Pescatore (i.e., the fisherman), was a Genoese adventurer, privateer and pirate active in the Mediterranean at the beginning of the thirteenth century. His real name is said to have been Erico or Arrigo di Castro or del Castel ...

, attacked Syracuse, which had only recently been occupied by Pisa. On 6 August, after a six-day siege, during which Alamanno destroyed two Pisan ships, the city fell. Alamanno was acclaimed count in the name of Genoa.

Count of Syracuse

Alamanno took the pompous and probably self-appointed title "by the grace of God

By the Grace of God ( la, Dei Gratia, abbreviated D.G.) is a formulaic phrase used especially in Christian monarchies as an introductory part of the full styles of a monarch. For example in England and later the United Kingdom, the phrase was fo ...

, the king and the commune of Genoa, Count of Syracuse 'comes Siracuse''and ''familiaris

In the Middle Ages, a ''familiaris'' (plural ''familiares''), more formally a ''familiaris regis'' ("familiar of the king") or ''familiaris curiae''In medieval documents, ''curiae'' may also be spelled ''curiæ'' or ''curie''. ("of the court"), ...

'' of the lord king". As historian David Abulafia

David Abulafia (born 12 December 1949) is an English historian with a particular interest in Italy, Spain and the rest of the Mediterranean during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. He spent most of his career at the University of Cambridge, ris ...

asserts, "it shard to understand what say the Genoese had in the appointment of the counts of a foreign kingdom", yet during the minority of the Sicilian king Frederick I Frederick I may refer to:

* Frederick of Utrecht or Frederick I (815/16–834/38), Bishop of Utrecht.

* Frederick I, Duke of Upper Lorraine (942–978)

* Frederick I, Duke of Swabia (1050–1105)

* Frederick I, Count of Zoller ...

they seem to have had a say. During his tenure, Sicily fell under Genoese hegemony, acting as a trading post, waystation and granary for the republic. It also became a centre of piracy. Alamanno's claim on Syracuse was not recognised by King Frederick I, who was also the Emperor Frederick II. He was thus excluded from the treaty between Genoa and Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc ...

in 1208, which excluded all "corsairs who reside in or work out of Sicily" (''cursales qui in Siciliam morantur vel consuetudinem'').

Alamanno was in a close alliance with Enrico Pescatore, to whom he lent the use of the ''Leopardo''. They raided the eastern Mediterranean as far as the County of Tripoli

The County of Tripoli (1102–1289) was the last of the Crusader states. It was founded in the Levant in the modern-day region of Tripoli, northern Lebanon and parts of western Syria which supported an indigenous population of Christians, Druze ...

; and both hosted the ''trobador

A troubadour (, ; oc, trobador ) was a composer and performer of Old Occitan lyric poetry during the High Middle Ages (1100–1350). Since the word ''troubadour'' is etymologically masculine, a female troubadour is usually called a ''trobairit ...

'' Peire Vidal

Peire Vidal ( fl. 12th century) was an Old Occitan troubadour. Forty-five of his songs are extant. The twelve that still have melodies bear testament to the deserved nature of his musical reputation.

There is no contemporary reference to Peire o ...

, who repaid them with lavish praise. In 1205, off the coast of Provence

Provence (, , , , ; oc, Provença or ''Prouvènço'' , ) is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which extends from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the Italian border to the east; it is bor ...

, three Pisan ''navi'' captured a Genoese ''nave'', the ''Viola'', on its way to ''al-Bijāya''. The captured ship was taken to Cagliari

Cagliari (, also , , ; sc, Casteddu ; lat, Caralis) is an Italian municipality and the capital of the island of Sardinia, an autonomous region of Italy. Cagliari's Sardinian name ''Casteddu'' means ''castle''. It has about 155,000 inhabitant ...

and thence to Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in ...

. There it joined a combined Pisan force of ''navi'' and twelve galley

A galley is a type of ship that is propelled mainly by oars. The galley is characterized by its long, slender hull, shallow draft, and low freeboard (clearance between sea and gunwale). Virtually all types of galleys had sails that could be used ...

s and landed a party to attack a Genoese force in the area. The sources are unclear if there were four ''navi'' or ten. Two of the galleys were dispatched to Palermo

Palermo ( , ; scn, Palermu , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan ...

, where they were intercepted and captured by a force of galleys under Alamanno, one of whose ships was commanded by his son. Shortly after, a Pisan fleet of ten ''navi'' and twelve galleys (with "many other vessels") and an army under Count Ranieri di Manenta besieged Syracuse for three-and-a-half months. In December 1205, a combined force under Alamanno—who had been leading the defence of the city—and Enrico lifted the siege. Enrico had been at Messina gathering a relief force. Originally it comprised four galleys, some ''taride

Horse transports in the Middle Ages were boats used for effective means of transporting horses over long distances, whether for war or general transport. They can be found from the Early Middle Ages, in Celtic, Germanic and Mediterranean tradition ...

'' (horse transports) and two Genoese ''navi'' that were returning from Outremer

The Crusader States, also known as Outremer, were four Catholic realms in the Middle East that lasted from 1098 to 1291. These feudal polities were created by the Latin Catholic leaders of the First Crusade through conquest and political int ...

. The Genoese convinced him to augment this force with more galleys and smaller vessels, as well as sixteen more ''navi'', apparently the most powerful ship class, before attacking the Pisan fleet at Syracuse. The latter contained some nine ''navi'', twelve galleys and fourteen other ships the chronicler refers to merely as ''buciisque et barchis'' (''bucio''s and ''barche'').

Activities in the East

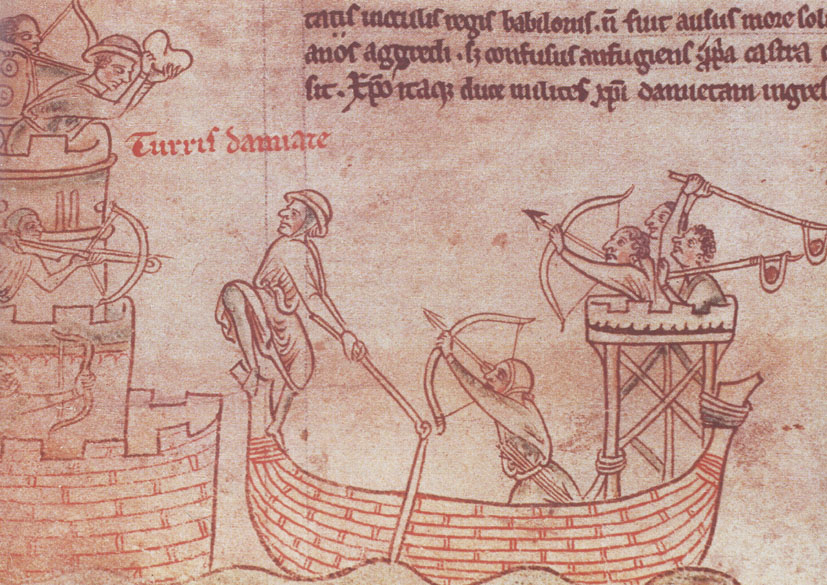

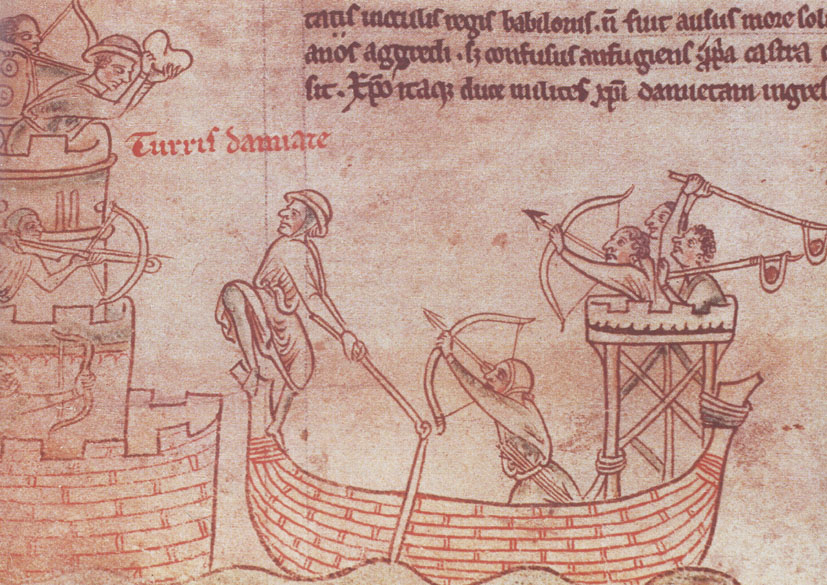

In 1216, Alamanno assisted Enrico in an attempt to conquer

In 1216, Alamanno assisted Enrico in an attempt to conquer Byzantine Crete

The island of Crete came under the rule of the Byzantine Empire in two periods: the first extends from the late antique period (3rd century) to the conquest of the island by Andalusian exiles in the late 820s, and the second from the island's rec ...

, to which Venice made claim. In June 1217, he was captured by the Venetians under Marco Zorzano and imprisoned in an iron cage. In 1218 Enrico renounced any claim he had on Crete in favour of Venice and Alamanno was released. In 1219, Alamanno led one galley in support of the Fifth Crusade

The Fifth Crusade (1217–1221) was a campaign in a series of Crusades by Western Europeans to reacquire Jerusalem and the rest of the Holy Land by first conquering Egypt, ruled by the powerful Ayyubid sultanate, led by al-Adil, brother of Sala ...

, and was present at the fall of Damietta.

In 1220 Frederick II began asserting royal rights in Syracuse, attempting to throw out the Genoese, and proclaiming the city "most faithful" (''fidelissima''). The emperor expropriated the warehouses and other properties belonging to Genoa. After he was expelled from the city in 1221, Alamanno went to Terracina

Terracina is an Italian city and ''comune'' of the province of Latina, located on the coast southeast of Rome on the Via Appia ( by rail). The site has been continuously occupied since antiquity.

History Ancient times

Terracina appears in anci ...

, where Pope Honorius III

Pope Honorius III (c. 1150 – 18 March 1227), born Cencio Savelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 18 July 1216 to his death. A canon at the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, he came to hold a number of importa ...

recommended him to the consuls of the city. In February 1224, Honorius took Alamanno, his family and his possessions under his protection while he was away on crusade. He had agreed to assist the margrave William VI of Montferrat

William VI (c. 1173 – 17 September 1225) was the tenth Marquis of Montferrat from 1203 and titular King of Thessalonica from 1207.

Biography Youth

Boniface I's eldest son, and his only son by his first wife, Helena del Bosco, William stood or ...

in the reconquest of the Kingdom of Thessalonica

The Kingdom of Thessalonica () was a short-lived Crusader State founded after the Fourth Crusade over conquered Byzantine lands in Macedonia and Thessaly.

History

Background

After the fall of Constantinople to the crusaders in 1204, Bonifac ...

in exchange for "one hundred knights or knight's fees

In feudal Anglo-Norman England and Ireland, a knight's fee was a unit measure of land deemed sufficient to support a knight. Of necessity, it would not only provide sustenance for himself, his family, and servants, but also the means to furnish him ...

" (''centum militias seu militaria feuda'') or one thousand marks of silver, guaranteed by Honorius. He probably died during the expedition. He was certainly deceased by 1229, when the ''podestà

Podestà (, English: Potestate, Podesta) was the name given to the holder of the highest civil office in the government of the cities of Central and Northern Italy during the Late Middle Ages. Sometimes, it meant the chief magistrate of a city ...

'' of Genoa, Iacopo di Balduino, wrote to the judge of Logudoro

The kings or ''judges'' (''iudices'' or ''judikes'') of Logudoro (or Torres) were the local rulers of the ''locum de Torres'' or region (province) around Porto Torres, the chief northern port of Sardinia, during the Middle Ages.

:''The identity, ...

, Marianus II, ordering him not to give assistance to Caroccino, the illegitimate son of Alamanno, accused of "acts of piracy after the fashion of his father" (''exercere pyraticam more patris'').

Notes

Sources

* * * * * *{{cite encyclopedia , last=Pryor , first=John H. , title=The Maritime Republics , encyclopedia=The New Cambridge Medieval History , volume=V , editor=David Abulafia , editor-link=David Abulafia , location=Cambridge , publisher=Cambridge University Press , year=1999 , pages=419–46 1220s deaths 13th-century Genoese people Counts of Syracuse Medieval pirates Christians of the Fifth Crusade Year of birth unknown Prisoners and detainees of the Republic of Venice Genoese admirals