Al-Faluja on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

al-Faluja ( ar, الفالوجة) was a

Palestinian Arab

Palestinians ( ar, الفلسطينيون, ; he, פָלַסְטִינִים, ) or Palestinian people ( ar, الشعب الفلسطيني, label=none, ), also referred to as Palestinian Arabs ( ar, الفلسطينيين العرب, label=non ...

village in the British Mandate for Palestine

The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British administration of the territories of Palestine and Transjordan, both of which had been conceded by the Ottoman Empire following the end of World War I in 1918. The mandate ...

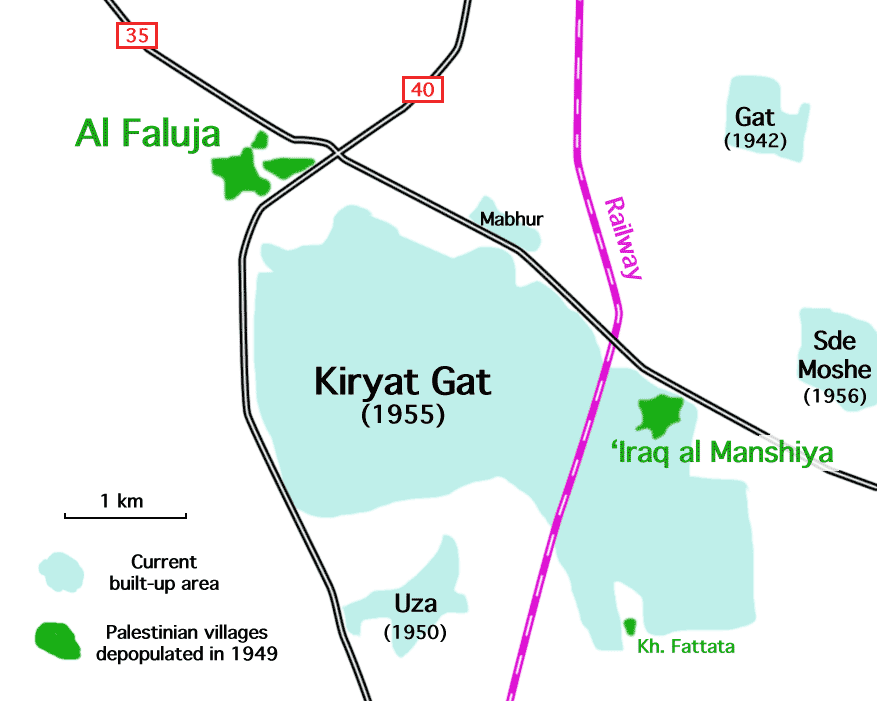

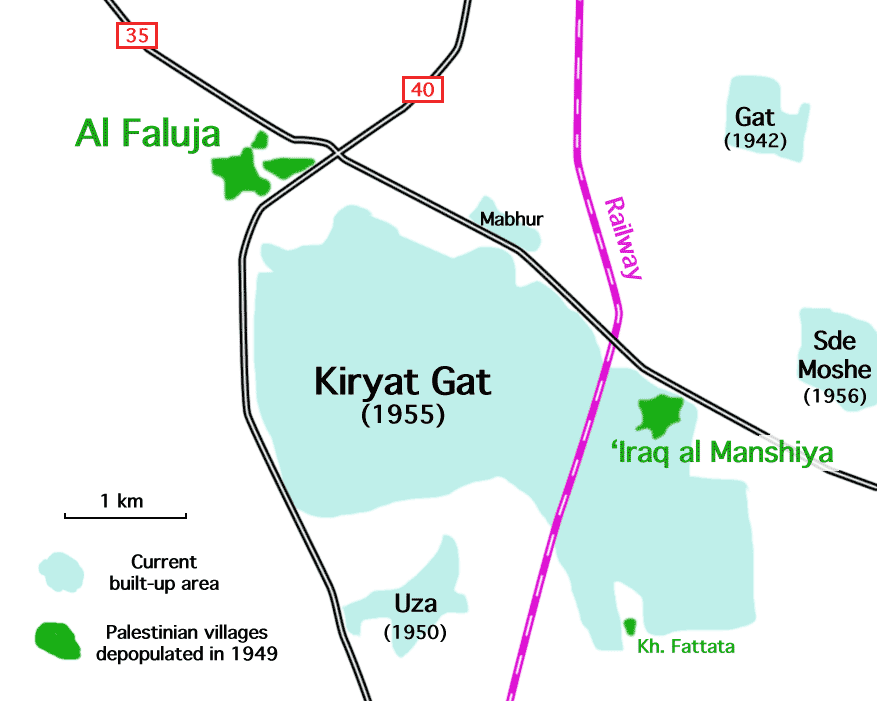

, located 30 kilometers northeast of Gaza City. The village and the neighbouring village of Iraq al-Manshiyya formed part of the Faluja pocket, where 4,000 Egyptian troops, who had entered the area as a result of the 1948 war

The 1948 Palestine war was fought in the territory of what had been, at the start of the war, British-ruled Mandatory Palestine. It is known in Israel as the War of Independence ( he, מלחמת העצמאות, ''Milkhemet Ha'Atzma'ut'') and ...

, were besieged for four months by the newly established Israel Defense Forces. The 1949 Armistice Agreements

The 1949 Armistice Agreements were signed between Israel and Egypt, Following the agreements, the Arab residents were harassed and abandoned the villages. The

119

/ref> though he did not visit it. In 1863

154

/ref> In 1883, the Palestine Exploration Fund's ''

In the

In the

3

The nucleus of the village was centered around the shrine of Shaykh al-Faluji. Its residential area began to expand in the 1930s and eventually crossed over to the other side of the wadi, which henceforth divided al-Faluja into northern and southern sections. Bridges were constructed across the wadi to facilitate movement between the two sides, especially during the winter when the water often flooded and caused damage. The center of al-Faluja shifted to the north where modern houses, stores, coffee houses, and a clinic were erected. The village had also two schools; one for boys (built in 1919) and the other for girls (built in 1940).

In the 1945 statistics Al-Faluja had a population of 4,670, all Muslims, with a total of 38,038 dunams of land, according to an official land and population survey. Of this, 87 dunams were used for plantations and irrigable land, 36,590 for cereals, while a total of 517 dunams were built-up (urban) land.

In the 1945 statistics Al-Faluja had a population of 4,670, all Muslims, with a total of 38,038 dunams of land, according to an official land and population survey. Of this, 87 dunams were used for plantations and irrigable land, 36,590 for cereals, while a total of 517 dunams were built-up (urban) land.

by Professor

Archived

from the original on 2007-06-15. Retrieved 2015-03-27. A battle between Jewish forces and villagers in al-Faluja on 14 March 1948 left thirty-seven Arabs and seven Jews dead, as well as scores of Arabs and four Jews wounded. Israeli sources at the time told the ''New York Times'' that a supply convoy, protected by armored cars of the

''San Francisco Chronicle''. July 8, 2002. Accessed 26th June 2007. The agreement (uniquely to the two villages), guaranteed the safety and property of the 3,140 Arab civilians (over 2,000 locals, plus refugees from other villages). The agreement, and a further exchange of letters filed with the United Nations, stated ''".... those of the civilian population who may wish to remain in al-Faluja and Iraq al-Manshiya are to be permitted to do so. ... All of these civilians shall be fully secure in their persons, abodes, property and personal effects."''

524

/ref> The last civilians left on 22 April, and the order to demolish these (and a string of other) villages was made 5 days later by Rabin.Rabin to 3rd Brigade, 26 April 1949, IDFA 979\51\\17. Cited by Morris, 2004, p

524

/ref>

183

ff) *

al-Faluja

IAAWikimedia commons

from the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

Al-Faluja

by

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

i town of Kiryat Gat

Kiryat Gat, also spelled Qiryat Gat ( he, קִרְיַת גַּת), is a city in the Southern District of Israel. It lies south of Tel Aviv, north of Beersheba, and from Jerusalem. In it had a population of . The city hosts one of the most a ...

, as well as the moshav

A moshav ( he, מוֹשָׁב, plural ', lit. ''settlement, village'') is a type of Israeli town or settlement, in particular a type of cooperative agricultural community of individual farms pioneered by the Labour Zionists between 1904 ...

Revaha

Revaha ( he, רְוָחָה, ''lit.'' prosperity) is a religious moshav in south-central Israel. Located in the southern Shephelah near Kiryat Gat, it falls under the jurisdiction of Shafir Regional Council. In it had a population of .

History

...

, border the site of the former town.

History

Until the Bar Kochba revolt, there was a large Jewish village called Kfar Shahalim. After the Arab conquest of the Land of Israel, a sign was erected on its ruins. The town was founded on a site that had been known as "Zurayq al-Khandaq", named "Zurayq" from the blue-coloredlupin

''Lupinus'', commonly known as lupin, lupine, or regionally bluebonnet etc., is a genus of plants in the legume family Fabaceae. The genus includes over 199 species, with centers of diversity in North and South America. Smaller centers occur ...

that grew in the vicinity. Its name was changed to "al-Faluja" in commemoration of a Sufi master, Shahab al-Din al-Faluji, who settled near the town after migrating there from Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

in the 14th century. He died in al-Faluja and his tomb was visited by the Syrian Sufi teacher and traveller Mustafa al-Bakri al-Siddiqi (1688-1748/9), who travelled through the region in the first half of the eighteenth century.Khalidi, 1992, p.95.

Ottoman era

In 1596, during the Ottoman era, Al-Faluja was under the administration of the ''nahiya

A nāḥiyah ( ar, , plural ''nawāḥī'' ), also nahiya or nahia, is a regional or local type of administrative division that usually consists of a number of villages or sometimes smaller towns. In Tajikistan, it is a second-level division w ...

'' of Gaza

Gaza may refer to:

Places Palestine

* Gaza Strip, a Palestinian territory on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea

** Gaza City, a city in the Gaza Strip

** Gaza Governorate, a governorate in the Gaza Strip Lebanon

* Ghazzeh, a village in ...

, part of the Sanjak of Gaza

Gaza Sanjak ( ar, سنجق غزة) was a sanjak of the Damascus Eyalet, Ottoman Empire centered in Gaza. In the 16th century it was divided into ''nawahi'' (singular: ''nahiya''; third-level subdivisions): Gaza in the south and Ramla in the north. ...

, with a population of 75 Muslim households, an estimated 413 persons. The villagers paid a fixed tax rate of 25% on wheat, barley, sesame, fruits, vineyards, beehives, goats, and water buffalo

The water buffalo (''Bubalus bubalis''), also called the domestic water buffalo or Asian water buffalo, is a large bovid originating in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. Today, it is also found in Europe, Australia, North America, S ...

; a total of 5,170 akçe. Half of the revenue went to a waqf

A waqf ( ar, وَقْف; ), also known as hubous () or ''mortmain'' property is an inalienable charitable endowment under Islamic law. It typically involves donating a building, plot of land or other assets for Muslim religious or charitabl ...

.

In 1838, Robinson Robinson may refer to:

People and names

* Robinson (name)

Fictional characters

* Robinson Crusoe, the main character, and title of a novel by Daniel Defoe, published in 1719

Geography

* Robinson projection, a map projection used since the 1960s ...

noted ''el Falujy'' as a Muslim village in the Gaza district,Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, Appendix 2, p.119

/ref> though he did not visit it. In 1863

Victor Guérin

Victor Guérin (15 September 1821 – 21 Septembe 1890) was a French intellectual, explorer and amateur archaeologist. He published books describing the geography, archeology and history of the areas he explored, which included Greece, Asia Min ...

found six hundred inhabitants in the village. He also noticed near a well

A well is an excavation or structure created in the ground by digging, driving, or drilling to access liquid resources, usually water. The oldest and most common kind of well is a water well, to access groundwater in underground aquifers. T ...

, two ancient columns of gray-white marble, and next to a wali

A wali (''wali'' ar, وَلِيّ, '; plural , '), the Arabic word which has been variously translated "master", "authority", "custodian", "protector", is most commonly used by Muslims to indicate an Islamic saint, otherwise referred to by t ...

, a third similar but rather destroyed. An Ottoman village list from about 1870 found that Faluja had a population of 670, in 230 houses, though the population count only included men.Socin, 1879, p154

/ref> In 1883, the Palestine Exploration Fund's ''

Survey of Western Palestine

The PEF Survey of Palestine was a series of surveys carried out by the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF) between 1872 and 1877 for the Survey of Western Palestine and in 1880 for the Survey of Eastern Palestine. The survey was carried out after th ...

'' described al-Faluja as surrounded on three sides by a wadi

Wadi ( ar, وَادِي, wādī), alternatively ''wād'' ( ar, وَاد), North African Arabic Oued, is the Arabic term traditionally referring to a valley. In some instances, it may refer to a wet ( ephemeral) riverbed that contains water on ...

. It had two wells

Wells most commonly refers to:

* Wells, Somerset, a cathedral city in Somerset, England

* Well, an excavation or structure created in the ground

* Wells (name)

Wells may also refer to:

Places Canada

* Wells, British Columbia

England

* Wel ...

and a pool to the east, a small garden patch to the west, and the village houses were built from adobe

Adobe ( ; ) is a building material made from earth and organic materials. is Spanish for '' mudbrick''. In some English-speaking regions of Spanish heritage, such as the Southwestern United States, the term is used to refer to any kind of ...

bricks.

British Mandate era

In the

In the 1922 census of Palestine

The 1922 census of Palestine was the first census carried out by the authorities of the British Mandate of Palestine, on 23 October 1922.

The reported population was 757,182, including the military and persons of foreign nationality. The divis ...

conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Al-Faluja had a population of 2,482 inhabitants; 2,473 Muslims, 3 Jews and 6 Christians, where the Christians were all of the Orthodox faith. The population increased in the 1931 census to 3,161 inhabitants; 2 Christians and all the rest Muslim, in a total of 683 houses.Mills, 1932, p3

The nucleus of the village was centered around the shrine of Shaykh al-Faluji. Its residential area began to expand in the 1930s and eventually crossed over to the other side of the wadi, which henceforth divided al-Faluja into northern and southern sections. Bridges were constructed across the wadi to facilitate movement between the two sides, especially during the winter when the water often flooded and caused damage. The center of al-Faluja shifted to the north where modern houses, stores, coffee houses, and a clinic were erected. The village had also two schools; one for boys (built in 1919) and the other for girls (built in 1940).

In the 1945 statistics Al-Faluja had a population of 4,670, all Muslims, with a total of 38,038 dunams of land, according to an official land and population survey. Of this, 87 dunams were used for plantations and irrigable land, 36,590 for cereals, while a total of 517 dunams were built-up (urban) land.

In the 1945 statistics Al-Faluja had a population of 4,670, all Muslims, with a total of 38,038 dunams of land, according to an official land and population survey. Of this, 87 dunams were used for plantations and irrigable land, 36,590 for cereals, while a total of 517 dunams were built-up (urban) land.

1948 Arab-Israeli war

Al-Faluja was in the territory allotted to the Arab state under the 1947 UN Partition Plan. During the war, the men of the village blockaded the local Jewish communities and attacked convoys being sent to bring them food, water, and other supplies. On 24 February 1948, the village was attacked by Jewish forces.Alfalouja text of "All that Remains"by Professor

Walid Khalidi

Walid Khalidi ( ar, وليد خالدي, born 1925 in Jerusalem) is an Oxford University-educated Palestinian historian who has written extensively on the Palestinian exodus. He is a co-founder of the Institute for Palestine Studies, establish ...

, Institute for Palestine Studies (November 1992)Archived

from the original on 2007-06-15. Retrieved 2015-03-27. A battle between Jewish forces and villagers in al-Faluja on 14 March 1948 left thirty-seven Arabs and seven Jews dead, as well as scores of Arabs and four Jews wounded. Israeli sources at the time told the ''New York Times'' that a supply convoy, protected by armored cars of the

Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the Is ...

, "had to fight its way through the village." A Haganah demolition squad returned later in the day and blew up ten houses in the village, including the town hall.

Egyptian forces crossed into the former mandate on 15 May 1948 and a column of them were stopped by the Israelis near Ashdod

Ashdod ( he, ''ʾašdōḏ''; ar, أسدود or إسدود ''ʾisdūd'' or '' ʾasdūd'' ; Philistine: 𐤀𐤔𐤃𐤃 *''ʾašdūd'') is the sixth-largest city in Israel. Located in the country's Southern District, it lies on the Mediterra ...

. This column retreated to and encamped at al-Faluja and Iraq al-Manshiyya, the so-called Faluja pocket. Between late October 1948 and late February 1949 some 4,000 Egyptian troops were encircled and held under sieged here by Israeli forces; the siege was a formative period for Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein, . (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian politician who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced far-r ...

, who was a major in the Egyptian army at Al-Faluja during the siege.

Armistice agreement

As part of the terms of the February 4, 1949Israel–Egypt Armistice Agreement

The 1949 Armistice Agreements were signed between Israel and Egypt,Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein, . (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian politician who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced far-r ...

) agreed to return to Egypt.Intel chip plant located on disputed Israeli land''San Francisco Chronicle''. July 8, 2002. Accessed 26th June 2007. The agreement (uniquely to the two villages), guaranteed the safety and property of the 3,140 Arab civilians (over 2,000 locals, plus refugees from other villages). The agreement, and a further exchange of letters filed with the United Nations, stated ''".... those of the civilian population who may wish to remain in al-Faluja and Iraq al-Manshiya are to be permitted to do so. ... All of these civilians shall be fully secure in their persons, abodes, property and personal effects."''

Israel

Few civilians left when the Egyptian brigade withdrew on 26 February 1949 but Israelis promptly violated the armistice agreement and began to intimidate the populace into flight. United Nations observers reported to UN mediatorRalph Bunche

Ralph Johnson Bunche (; August 7, 1904 – December 9, 1971) was an American political scientist, diplomat, and leading actor in the mid-20th-century decolonization process and US civil rights movement, who received the 1950 Nobel Peace Prize f ...

that the intimidation included beatings, robberies, and attempted rape. Quaker observers bore witness to the beatings On 3 March they wrote that at ''" Iraq al Manshiya, the acting mukhtar

A mukhtar ( ar, مختار, mukhtār, chosen one; el, μουχτάρης) is a village chief in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximation, approximate historical geography, historical geographical term referring to a large area in t ...

or mayor told them that 'the people had been much molested by the frequent shooting, by being told that they would be killed if they did not go to Hebron, and by the Jews breaking into their homes and stealing things"''. Moshe Sharett

Moshe Sharett ( he, משה שרת, born Moshe Chertok (Hebrew: ) 15 October 1894 – 7 July 1965) was a Russian-born Israeli politician who served as Israel's second prime minister from 1954 to 1955. A member of Mapai, Sharett's term was ...

(Israeli Foreign Minister) was very concerned at the international repercussions, especially the possible effect on Israeli-Egyptian relations. He was angry at the actions of the IDF, carried out without Cabinet authorization and behind his back and was not easily appeased. He used most uncharacteristic language ''"The IDF's actions"'' threw into question our sincerity as a party to an international agreement ... One may assume that Egypt in this matter will display special sensitivity as her forces saw themselves as responsible for the fate of these civilian inhabitants. There are also grounds to fear that any attack by us on the people of these two villages may be reflected in the attitude of the Cairo Government toward the Jews of Egypt.Sharett pointed out that Israel was seeking membership of the United Nations, and was encountering difficulties

over the question of our responsibility for the Arab refugee problem. We argue that we are not responsible ... From this perspective, the sincerity of our professions is tested by our behavior in these villages ... Every intentional pressure aimed at uprooting hese Arabsis tantamount to a planned act of eviction on our part.Sharett also protested that the IDF were carrying out a covert

whispering propaganda' campaign among the Arabs, threatening them with attacks and acts of vengeance by the army, which the civilian authorities will be powerless to prevent. This whispering propaganda (ta'amulat lahash) is not being done of itself. There is no doubt that here there is a calculated action aimed at increasing the number of those going to theHe also referred to the army's actions as ''"'an unauthorized initiative by the local command in a matter relating to Israeli government policy'"''. Allon admitted (to Yadin) only that his troops had ''"beaten three Arabs ... There is no truth to the observers' announcement about abuse/cruelty it'alelut etc. I investigated this personally."'' Morris further writes that the decision to cleanse the "Faluja pocket" population was approved by Israeli prime ministerHebron Hebron ( ar, الخليل or ; he, חֶבְרוֹן ) is a State of Palestine, Palestinian. city in the southern West Bank, south of Jerusalem. Nestled in the Judaean Mountains, it lies Above mean sea level, above sea level. The second-lar ...Hills as if of their own free will, and, if possible, to bring about the evacuation of the whole civilian population of he pocket

David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; he, דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder of the State of Israel and the first prime minister of Israel. Adopting the na ...

.Entry for 28 February 1949, Weitz, Diary, IV, 15; and Y Berdichevsky to Machnes, 3 Mar 1949, ISA MAM 297\60. Cited by Morris, 2004, p524

/ref> The last civilians left on 22 April, and the order to demolish these (and a string of other) villages was made 5 days later by Rabin.Rabin to 3rd Brigade, 26 April 1949, IDFA 979\51\\17. Cited by Morris, 2004, p

524

/ref>

See also

* Depopulated Palestinian locations in Israel *Operation Yoav

Operation Yoav (also called ''Operation Ten Plagues'' or ''Operation Yo'av'') was an Israeli military operation carried out from 15–22 October 1948 in the Negev Desert, during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. Its goal was to drive a wedge between t ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * (pp183

ff) *

External links

Zochrot

Zochrot ( he, זוכרות; "Remembering"; ar, ذاكرات; "Memories") is an Israeli nonprofit organization founded in 2002. Based in Tel Aviv, its aim is to promote awareness of the Palestinian ''Nakba'' ("Catastrophe"), including the 1948 P ...

*Survey of Western Palestine, Map 20IAA

from the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

Al-Faluja

by

Rami Nashashibi

Rami Nashashibi is a Palestinian-American activist, community organizer, sociologist, and Islamic studies scholar. He founded the nonprofit organization Inner-City Muslim Action Network in 1997, working as its executive director for many years, a ...

(1996), Center for Research and Documentation of Palestinian Society.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Faluja

1948 Arab–Israeli War

District of Gaza

Arab villages depopulated after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War