Air Mail Act on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Air Mail scandal, also known as the Air Mail fiasco, is the name that the American

The first scheduled airmail service in the United States was conducted during

The first scheduled airmail service in the United States was conducted during

U.S. Air Mail Service - 90th Anniversary

, reprinted at Antique Airfield.com. Retrieved 2016-01-03The first completed flight of the route was made by 2d Lt. James C. Edgerton on May 15, 1918, flying the Philadelphia to D.C. leg in s/n 38274. He brought 136 pounds of mail from New York, flown from As safety and capability grew, daytime-only operations gave way to flying at night, assisted by

As safety and capability grew, daytime-only operations gave way to flying at night, assisted by

Hoover appointed Brown as postmaster general in 1929. In 1930, with the nation's airlines apparently headed for extinction in the face of a severe economic downturn and citing inefficient, expensive subsidized air mail delivery, Brown requested supplementary legislation to the 1925 act granting him authority to change postal policy. The Air Mail Act of 1930, passed on April 29 and known as the McNary-Watres Act after its chief sponsors, Sen.

Hoover appointed Brown as postmaster general in 1929. In 1930, with the nation's airlines apparently headed for extinction in the face of a severe economic downturn and citing inefficient, expensive subsidized air mail delivery, Brown requested supplementary legislation to the 1925 act granting him authority to change postal policy. The Air Mail Act of 1930, passed on April 29 and known as the McNary-Watres Act after its chief sponsors, Sen.

The air mail scandal began when an officer of the New York Philadelphia and Washington Airway Corporation, known as the

The air mail scandal began when an officer of the New York Philadelphia and Washington Airway Corporation, known as the

press

Press may refer to:

Media

* Print media or news media, commonly called "the press"

* Printing press, commonly called "the press"

* Press (newspaper), a list of newspapers

* Press TV, an Iranian television network

People

* Press (surname), a fam ...

gave to the political scandal

In politics, a political scandal is an action or event regarded as morally or legally wrong and causing general public outrage. Politicians, government officials, party officials and lobbyists can be accused of various illegal, corrupt, unethic ...

resulting from a 1934 congressional investigation of the awarding of contracts to certain airline

An airline is a company that provides civil aviation, air transport services for traveling passengers and freight. Airlines use aircraft to supply these services and may form partnerships or Airline alliance, alliances with other airlines for ...

s to carry airmail

Airmail (or air mail) is a mail transport service branded and sold on the basis of at least one leg of its journey being by air. Airmail items typically arrive more quickly than surface mail, and usually cost more to send. Airmail may be the ...

and to the use of the U.S. Army Air Corps

The United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) was the aerial warfare service component of the United States Army between 1926 and 1941. After World War I, as early aviation became an increasingly important part of modern warfare, a philosophical ri ...

to fly the mail.

In 1930, during the administration of President Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

, Congress passed the Air Mail Act of 1930. Using its provisions, Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having a government official respons ...

Walter Folger Brown

Walter Folger Brown (May 31, 1869January 26, 1961) was an American politician and lawyer who is served as the Postmaster General of the United States from March 5, 1929 to March 4, 1933 under Herbert Hoover's administration.

Biography Early & p ...

held a meeting with the executives of the top airlines, later dubbed the "Spoils Conference", in which the airlines effectively divided among themselves the air mail

Airmail (or air mail) is a mail transport service branded and sold on the basis of at least one leg of its journey being by air. Airmail items typically arrive more quickly than surface mail, and usually cost more to send. Airmail may be the ...

routes. Acting on those agreements, Brown awarded contracts to the participants through a process that effectively prevented smaller carriers from bidding, resulting in a Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

investigation.

The Senate investigation resulted in a citation of Contempt of Congress

Contempt of Congress is the act of obstructing the work of the United States Congress or one of its committees. Historically, the bribery of a U.S. senator or U.S. representative was considered contempt of Congress. In modern times, contempt of Co ...

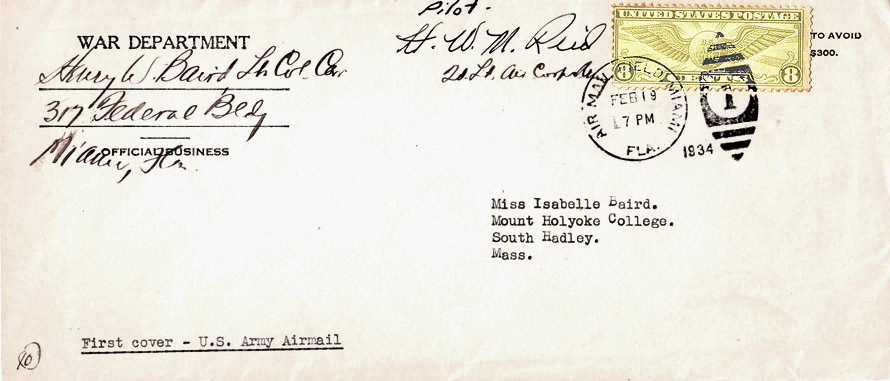

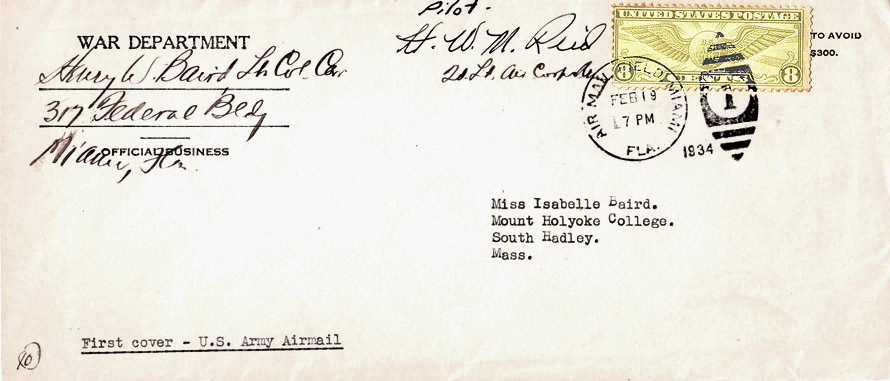

against William P. MacCracken Jr., on February 5, 1934, the only action taken against any former Hoover administration official for the scandal. Two days later Roosevelt cancelled all existing air mail contracts with the airlines and ordered the Air Corps to deliver the mail until new contracts could be let. The Air Corps was ill-prepared to conduct a mail operation, particularly at night, and from its outset on February 19 encountered severe winter weather. The Army Air Corps Mail Operation suffered numerous crashes and the deaths of 13 airmen, causing severe public criticism of the Roosevelt Administration.

Temporary contracts were put into effect on May 8 by the new postmaster general, James A. Farley, in a manner nearly identical to that of the "Spoils Conference" that started the scandal. Service was completely restored to the airlines by June 1, 1934. On June 12 Congress passed a new Air Mail Act cancelling the provisions of the 1930 law and enacting punitive measures against executives who were a part of the Spoils Conferences. Although a public relations nightmare for the administrations of both presidents, the scandal resulted in the restructuring of the airline industry, leading to technological improvements and a new emphasis on passenger operations, and the modernization of the Air Corps.

Roots of the scandal

Development of air mail

The first scheduled airmail service in the United States was conducted during

The first scheduled airmail service in the United States was conducted during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

by the Air Service of the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

between May 15 and August 10, 1918, a daily run between Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, and New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

with an intermediate stop in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

. The operation was put together in ten days by Major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

Reuben H. Fleet

Reuben Hollis Fleet (March 6, 1887 – October 29, 1975) was an American aviation pioneer, industrialist and army officer. Fleet founded and led several corporations, including Consolidated Aircraft.

Birth and early career

Fleet was born on Mar ...

, the executive officer for flying training of the Division of Military Aeronautics

The Division of Military Aeronautics was the name of the aviation organization of the United States Army for a four-day period during World War I. It was created by a reorganization by the War Department of the Aviation Section, U.S. Signal Corps ...

, and managed by Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Benjamin B. Lipsner, a non-flyer. Starting with six converted Curtiss JN-4HM "Jennies", two of which were destroyed in crashes, and later using Curtiss R-4LMs, in 76 days of operations Air Service pilots moved 20 tons of mail without a single fatality or serious injury, achieving a 74% completion rate of flights during the summer thunderstorm season.John A. EneyU.S. Air Mail Service - 90th Anniversary

, reprinted at Antique Airfield.com. Retrieved 2016-01-03The first completed flight of the route was made by 2d Lt. James C. Edgerton on May 15, 1918, flying the Philadelphia to D.C. leg in s/n 38274. He brought 136 pounds of mail from New York, flown from

Hazelhurst Field

Roosevelt Field is a former airport, located east-southeast of Mineola, Long Island, New York. Originally called the Hempstead Plains Aerodrome, or sometimes Hempstead Plains field or the Garden City Aerodrome, it was a training field (Hazel ...

on Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United Sta ...

to Philadelphia by Lt. Torrey H. Webb in s/n 38278, who also delivered eight pounds of mail to the Philadelphia postmaster. An identical relay flight in the opposite direction, carrying a ceremonial letter from the president to the postmaster of New York, was begun from D.C. by Lt. George L. Boyle in s/n 38262 after an embarrassing delay in front of the gathered audience when he was unable to start the engine. Boyle and Edgerton had been added to the operation by the Post Office Department for their political connections. Edgerton's father was purchasing agent for the Department and Boyle's prospective father-in-law, Judge Charles C. McChord, was an appointed official in the Wilson Administration who had kept delivery of parcel post as the responsibility of the post office. Both had just graduated from flying training at Ellington Field

Ellington Field Joint Reserve Base is a joint installation shared by various active component and reserve component military units, as well as aircraft flight operations of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) under the aegis ...

in Texas and had only 60 hours student pilot experience. They were chosen to replace two experienced instructor pilots hand-picked by Fleet to make the first day's flights. Boyle got lost in the fog shortly after takeoff and force-landed in a farm field 25 miles outside Washington, headed in the wrong direction. Edgerton delivered Boyle's load the next day on his return trip and eventually made 52 mail flights in the initial operation. He moved over to the post office operation later in 1918 as superintendent of flight operations under Lipsner. The less fortunate Boyle got a second chance on May 17, but even though he was led part of the way by another Jenny (depending on the account, flown by either Fleet or Edgerton), got lost again and wrecked his plane trying to land on a golf course. He was not given a third chance but did marry Margaret McChord on June 15, 1918 and went on to become a lawyer. (Eney and Glines)

Air mail operations by the U.S. Post Office

The United States Postal Service (USPS), also known as the Post Office, U.S. Mail, or Postal Service, is an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the executive branch of the Federal government of the Uni ...

began in August 1918 under Lipsner, who resigned from the Army on July 13 to take the post. Lipsner procured Standard JR-1B biplanes specially modified to carry the mail with twice the range of the military mailplanes, the first civil aircraft built to U.S. government specifications. For nine years, using mostly war-surplus de Havilland DH.4 biplanes, the Post Office built and flew a nationwide network. In the beginning the work was extremely dangerous; of the initial 40 pilots, three died in crashes in 1919 and nine more in 1920. It was 1922 before an entire year ensued without a fatal crash.

As safety and capability grew, daytime-only operations gave way to flying at night, assisted by

As safety and capability grew, daytime-only operations gave way to flying at night, assisted by airway beacon

An airway beacon (US) or aerial lighthouse (UK and Europe) was a rotating light assembly mounted atop a tower. These were once used extensively in the United States for visual navigation by airplane pilots along a specified airway corridor. ...

s and lighted emergency landing fields. Regular transcontinental air mail delivery began in 1924. In 1925, to encourage commercial aviation, the Kelly Act

The Air Mail Act of 1925, also known as the Kelly Act, was a key piece of legislation that intended to free the airmail from total control by the Post Office Department. In short, it allowed the Postmaster General to contract private companies to ...

(also known as the Air Mail Act of 1925) authorized the Post Office Department to contract with private airlines for feeder routes into the main transcontinental system. The first commercial air mail flight was on the route CAM (Contract Air Mail) No. 5 from Pasco, Washington

Pasco ( ) is a city in, and the county seat of, Franklin County, Washington, United States. It had a population of 59,781 at the 2010 census, and 75,432 as of the July 1, 2019 Census Bureau estimate.

Pasco is one of three cities (the others b ...

, to Elko, Nevada

Elko (Shoshoni: Natakkoa, "Rocks Piled on One Another") is the largest city in and county seat of Elko County, Nevada, United States. With a 2020 population of 20,564, Elko is currently growing at a rate of 0.31% annually and its population has i ...

, on April 6, 1926. By 1927 the transition had been completed to entirely commercial transport of mail, and by 1929 45 airlines were involved in mail delivery at a cost per mile of $1.10. Most were small, under-capitalized companies flying short routes and old equipment.

Subsidies for carrying mail exceeded the cost of the mail itself, and some carriers abused their contracts by flooding the system with junk mail at 100% profit or hauling heavy freight as air mail. Historian Oliver E. Allen, in his book ''The Airline Builders'', estimated that airlines would have had to charge a 150-pound passenger $450 per ticket (equal to $ in dollars) in lieu of carrying an equivalent amount of mail.

William P. MacCracken Jr.

William P. MacCracken Jr. became the first federal regulator ofcommercial aviation

Commercial aviation is the part of civil aviation that involves operating aircraft for remuneration or hire, as opposed to private aviation.

Definition

Commercial aviation is not a rigorously defined category. All commercial air transport and ae ...

when then-Secretary of Commerce

The United States secretary of commerce (SecCom) is the head of the United States Department of Commerce. The secretary serves as the principal advisor to the president of the United States on all matters relating to commerce. The secretary rep ...

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

named him the first Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Aeronautics in 1926. During World War I he had served as a flight instructor, had served on the Chicago Aeronautical Commission, and was a member of the board of governors of the National Aeronautical Association when selected by Hoover.

MacCracken left the Commerce Department in 1929 and returned to his private law practice, where he continued to be involved in the growth of commercial aviation by representing many major airline

An airline is a company that provides civil aviation, air transport services for traveling passengers and freight. Airlines use aircraft to supply these services and may form partnerships or Airline alliance, alliances with other airlines for ...

s.

Postmaster General Walter Folger Brown

Walter Folger Brown (May 31, 1869January 26, 1961) was an American politician and lawyer who is served as the Postmaster General of the United States from March 5, 1929 to March 4, 1933 under Herbert Hoover's administration.

Biography Early & p ...

sought to improve the efficiency of the air mail carriers in furtherance of a national transportation plan. Requiring an informed intermediary, Brown asked MacCracken to preside over what was later scandalized as the ''Spoils Conferences'', to work out an agreement between the carriers and the Post office to consolidate air mail routes into transcontinental networks operated by the best-equipped and financially stable companies. This relationship left both exposed to charges of favoritism. When MacCracken refused later to testify before the Senate, he was found in contempt of Congress

Contempt of Congress is the act of obstructing the work of the United States Congress or one of its committees. Historically, the bribery of a U.S. senator or U.S. representative was considered contempt of Congress. In modern times, contempt of Co ...

.

Air Mail Act of 1930

Hoover appointed Brown as postmaster general in 1929. In 1930, with the nation's airlines apparently headed for extinction in the face of a severe economic downturn and citing inefficient, expensive subsidized air mail delivery, Brown requested supplementary legislation to the 1925 act granting him authority to change postal policy. The Air Mail Act of 1930, passed on April 29 and known as the McNary-Watres Act after its chief sponsors, Sen.

Hoover appointed Brown as postmaster general in 1929. In 1930, with the nation's airlines apparently headed for extinction in the face of a severe economic downturn and citing inefficient, expensive subsidized air mail delivery, Brown requested supplementary legislation to the 1925 act granting him authority to change postal policy. The Air Mail Act of 1930, passed on April 29 and known as the McNary-Watres Act after its chief sponsors, Sen. Charles L. McNary

Charles Linza McNary (June 12, 1874February 25, 1944) was an American Republican Party (United States), Republican politician from Oregon. He served in the United States Senate, U.S. Senate from 1917 to 1944 and was Party leaders of the United ...

of Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

and Rep. Laurence H. Watres

Laurence Hawley Watres (July 18, 1882 – February 6, 1964) was a Republican member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania.

Early life and education

Laurence H. Watres was born in Scranton, Pennsylvania, to Louis Arthur Watres ...

of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, authorized the postmaster general to enter into longer-term airmail contracts with rates based on space or volume, rather than weight. The Act gave Brown strong authority (some argued almost dictatorial powers) over the nationwide air transportation system.

The main provision of the Air Mail Act changed the manner in which payments were calculated. Air mail carriers would be paid for having sufficient cargo capacity on their planes, whether the planes carried mail or flew empty, a disincentive to carry mail since the carrier received a set fee for a plane of a certain size whether or not it carried mail. The purpose of the provision was to discourage the carrying of bulk junk mail to boost profits, particularly by the smaller and inefficient carriers, and to encourage the carrying of passengers. Airlines using larger planes designed to carry passengers would increase their revenues by carrying more passengers and less mail. Awards would be made to the “lowest responsible bidder” that had owned an airline operated on a daily schedule of at least 250 miles (402 kilometers) for at least six months.

A second provision allowed any airmail carrier with an existing contract of at least two years standing to exchange its contract for a “route certificate” giving it the right to haul mail for 10 additional years. The third and most controversial provision gave Brown authority to "extend or consolidate" routes in effect according to his own judgment.

Within days of its passage, United Aircraft and Transport Company (UATC) acquired the controlling interest of National Air Transport

National Air Transport was a large United States airline; in 1930 it was bought by Boeing. The Air Mail Act of 1934 prohibited airlines and manufacturers from being under the same corporate umbrella, so Boeing split into three smaller companies, ...

after a brisk but brief struggle between UATC and Clement M. Keys of NAT. The merger, begun in February 1930 to plug the only gap in UATC's cross-country network of airlines, had been amicable until three weeks before its finalization, when Keys reversed his initial approval. Ironically Brown was angered by the negotiations, worried that the specter of a potential monopoly would endanger the imminent passage of the Air Mail Act. The merger swiftly created the first transcontinental airline.

On May 19, three weeks after the passage of McNary-Watres, at the first of the "Spoils Conferences", Brown invoked his authority under the third provision to consolidate the air mail routes to only three major companies independently competing with each other, with the goal of forcing the plethora of small, inefficient carriers to merge with the larger. Further meetings between the larger carriers, presided over by McCracken, continued into June that often developed into harsh wrangling over route distribution proposals and consequent animosity towards Brown.

After what was described as a "shotgun marriage

A shotgun wedding is a wedding which is arranged in order to avoid embarrassment due to premarital sex which can possibly lead to an unintended pregnancy. The phrase is a primarily American colloquialism, termed as such based on a stereotypic ...

" between Transcontinental Air Transport

Transcontinental Air Transport (T-A-T) was an airline founded in 1928 by Clement Melville Keys that merged in 1930 with Western Air Express to form what became TWA. Keys enlisted the help of Charles Lindbergh to design a transcontinental network t ...

and Western Air Express

Western Airlines was a major airline based in California, operating in the Western United States including Alaska and Hawaii, and western Canada, as well as to New York City, Boston, Washington, D.C., and Miami and to Mexico City, London and N ...

in July to achieve the second of the three companies (UATC was the first), competitive bids were solicited by the Post Office on August 2, 1930, and opened August 25. A surprise competitive bidding struggle ensued between UATC, through a quickly formed skeleton company it called "United Aviation," and the newly merged Transcontinental and Western Air

Trans World Airlines (TWA) was a major American airline which operated from 1930 until 2001. It was formed as Transcontinental & Western Air to operate a route from New York City to Los Angeles via St. Louis, Kansas City, and other stops, with ...

over the central transcontinental route. After initial rejection of the Postmaster General's decision, final approval of the contract award to T&WA was approved by Comptroller General of the United States

The Comptroller General of the United States is the director of the Government Accountability Office (GAO, formerly known as the General Accounting Office), a legislative-branch agency established by Congress in 1921 to ensure the fiscal and ma ...

John R. McCarl on January 10, 1931, on the basis that United's puppet concern was not a "responsible bidder" by the definition of McNary-Watres, in effect validating Brown's restructuring.

These three carriers later evolved into United Airlines

United Airlines, Inc. (commonly referred to as United), is a major American airline headquartered at the Willis Tower in Chicago, Illinois.

(the northern airmail route, CAMs 17 and 18), Trans World Airlines

Trans World Airlines (TWA) was a major American airline which operated from 1930 until 2001. It was formed as Transcontinental & Western Air to operate a route from New York City to Los Angeles via St. Louis, Kansas City, and other stops, with F ...

(the mid-United States route, CAM 34) and American Airlines

American Airlines is a major airlines of the United States, major US-based airline headquartered in Fort Worth, Texas, within the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex. It is the Largest airlines in the world, largest airline in the world when measured ...

(the southern route, CAM 33).The August 1930 bid was jointly awarded to the Southwest Air Fast Express, or SAFE Way, owned by Erle P. Halliburton

Erle Palmer Halliburton was an American businessman specializing in oil field services.

Early life

Halliburton was born on September 22, 1892, near Henning, Tennessee, the son of Lou Emma (Cothran) and Edwin Graves Halliburton. When Halliburton ...

, and Robertson Aircraft Corporation, like American a subsidiary of the Avco

Avco Corporation is a subsidiary of Textron which operates Textron Systems Corporation

and Lycoming.

History

The Aviation Corporation was formed on March 2, 1929, to prevent a takeover of CAM-24 airmail service operator Embry-Riddle Compa ...

holding company. SAFE Way was acquired by American at a premium price on August 23, 1930, two days before the bids were opened, and both lines were reorganized by American as Southern Air Fast Express. Brown also extended the southern route to the West Coast West Coast or west coast may refer to:

Geography Australia

* Western Australia

*Regions of South Australia#Weather forecasting, West Coast of South Australia

* West Coast, Tasmania

**West Coast Range, mountain range in the region

Canada

* Britis ...

. He awarded bonuses for carrying more passengers and purchasing multi-engined aircraft equipped with radios and navigation aids. By the end of 1932, the airline industry was the one sector of the economy experiencing steady growth and profitability, described by one historian as "Depression-proof." Passenger miles, the numbers of passengers, and new airline employees had all tripled over 1929. Airmail itself, despite its image to many Americans as a frivolous luxury for the few remaining affluent, had doubled following restructuring. Much of this if not all was the result of the postal subsidies, funded by taxpayers.Brady (2000), p. 177

Congressional investigation

The air mail scandal began when an officer of the New York Philadelphia and Washington Airway Corporation, known as the

The air mail scandal began when an officer of the New York Philadelphia and Washington Airway Corporation, known as the Ludington Airline

Ludington Airline (also, Ludington Lines or Ludington Line) was an airline of northeastern United States in the 1930s. It was unique as it was the first airline that carried passengers only and was not supported by government revenue from airmail ...

, was having a drink with friend and Hearst newspaper reporter Fulton Lewis Jr.

Fulton Lewis Jr. (April 30, 1903 in Washington D.C. – August 20, Lists his death date as 21 August, but other references show the death date to be 20 August. 1966 in Washington D. C.) was a conservative American radio broadcaster from the 1930 ...

Ludington Airline, established and owned by brothers Townsend and Nicholas Ludington, began offering an hourly daytime passenger shuttle on September 1, 1930, just two weeks after Eastern Air Transport (EAT) began its first passenger operations between New York City and Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

. Using seven Stinson SM-6000B tri-motors, Ludington Airline became the first U. S. airline in history to make a profit carrying nothing but passengers. However it began operating in the red when the novelty of cheap air travel wore off as the Great Depression deepened and competition with arch-rival EAT intensified. The Ludington officer mentioned to Lewis that in 1931 the carrier could not get a proposed "express service" air mail contract to extend CAM 25 (Miami to Washington via Atlanta) to Newark, New Jersey

Newark ( , ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of New Jersey and the seat of Essex County and the second largest city within the New York metropolitan area.cents a mile. Ludington's general manager, former Air Service aviator Eugene L. Vidal, eager to curtail Ludington's growing losses with a lucrative mail subsidy, had offered the extremely low bid to Brown in order to demonstrate Ludington's commitment to the route extension plan "at or below cost."The concept for the shuttle was Vidal's. He and veteran airmail pilot Paul Collins had left the financially strapped Transcontinental Air Transport in 1930 and persuaded the Ludington brothers to financially back Vidal's idea on an experimental basis.

Justia.com. Retrieved 2016-02-09 During a five-day trial the Senate deemed him a

Without consulting either Army Chief of Staff

Without consulting either Army Chief of Staff

The Air Corps during the Great Depression, hampered by pay cuts and a reduction of flight time, operated almost entirely in daylight and good weather. Duty hours were limited and relaxed, usually with four hours or less of flight operations a day, and none on weekends. Experience levels were also limited by obsolete aircraft, most of them single-engine and open cockpit planes. Because of a high turnover-rate policy in the War Department, most pilots were Reserve officers who were unfamiliar with the civilian airmail routes.

Regarding equipment, the Air Corps had in its inventory 274

The Air Corps during the Great Depression, hampered by pay cuts and a reduction of flight time, operated almost entirely in daylight and good weather. Duty hours were limited and relaxed, usually with four hours or less of flight operations a day, and none on weekends. Experience levels were also limited by obsolete aircraft, most of them single-engine and open cockpit planes. Because of a high turnover-rate policy in the War Department, most pilots were Reserve officers who were unfamiliar with the civilian airmail routes.

Regarding equipment, the Air Corps had in its inventory 274

"'Fiasco' revisited: the Air Corps & the 1934 air mail episode"

''Air Power History'', March 22, 2010. Reproduced by The Free Library, thefreelibary.com. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

On February 19, the blizzard disrupted the initial day's operations east of the

On February 19, the blizzard disrupted the initial day's operations east of the  In the Western Zone, Arnold established his headquarters in

In the Western Zone, Arnold established his headquarters in  On February 22 a young pilot departing Chicago in an O-39 flew into a snow storm over

On February 22 a young pilot departing Chicago in an O-39 flew into a snow storm over

On March 8 and 9, 1934, four more pilots died in crashes,Lts. Frank L. Howard and Arthur R. Kerwin, Jr. in the crash of an O-38E at

On March 8 and 9, 1934, four more pilots died in crashes,Lts. Frank L. Howard and Arthur R. Kerwin, Jr. in the crash of an O-38E at

In all, 66 major accidents, ten of them with fatalities,By comparison and also conducted in bad weather, the much larger and longer

In all, 66 major accidents, ten of them with fatalities,By comparison and also conducted in bad weather, the much larger and longer

Ironically, of the major carriers present at the "Spoils Conference", all received new contracts for their old routes with the exception of United, "the one airline completely innocent of any possible charge of collusion."Van der Linden (2002), p. 284Post Office Solicitor and Fort Worth attorney Karl Crowley held that United's presence at the conference was sufficient evidence of guilt and denied it a hearing to present its case. (Van der Linden, p. 285). United's routes were awarded instead to regional independents

Ironically, of the major carriers present at the "Spoils Conference", all received new contracts for their old routes with the exception of United, "the one airline completely innocent of any possible charge of collusion."Van der Linden (2002), p. 284Post Office Solicitor and Fort Worth attorney Karl Crowley held that United's presence at the conference was sufficient evidence of guilt and denied it a hearing to present its case. (Van der Linden, p. 285). United's routes were awarded instead to regional independents

On April 17, 1934, well before AACMO ended,Dern began putting together the Baker Board as soon as he received the letter from Roosevelt emanating from the March 10 tongue-lashing of MacArthur and Foulois. He hoped to divert attention from the AACMO crisis, especially in Congress where the house hearings on the pending autonomy bills were in full swing, by using an investigative board as

On April 17, 1934, well before AACMO ended,Dern began putting together the Baker Board as soon as he received the letter from Roosevelt emanating from the March 10 tongue-lashing of MacArthur and Foulois. He hoped to divert attention from the AACMO crisis, especially in Congress where the house hearings on the pending autonomy bills were in full swing, by using an investigative board as

"The Air Mail Fiasco", ''AIR FORCE Magazine'', March 2008, Vol. 91, No. 3

* Duffy, James P. (2010). ''Lindbergh vs. Roosevelt: The Rivalry That Divided America''. Washington, D.C.:Regnery Publishing. * * Frisbee, John L

"AACMO—Fiasco or Victory?", ''AIR FORCE Magazine'', March 1995, Vol. 78 No. 3

* Glines, Carroll F

Aerofiles.com. Retrieved 2016-01-04 * Hamilton, Virginia Van der Veer. "Barnstorming the U.S. Mail", ''American Heritage'' August 1974; Volume 25, Issue 5, pp. 32–35 * Hopkins, George E. (1982). ''Flying the Line: The First Half Century of the Air Line Pilots Association''. Washington, D.C.:ALPA. * Lee, David D. "Senator Black's Investigation of the Airmail, 1933-1934", ''The Historian'' Spring 1991; Volume 53, pp. 423–442 * Maurer, Maurer (1987). ''Aviation in the U.S. Army, 1919–1939'', Office of Air Force History, Washington, D.C. * Nalty, Bernard C. (1997). ''Winged Shield, Winged Sword: A History of the United States Air Force'', * Orenic, Liesl (2009). ''On the Ground: Labor Struggles in the American Airline Industry''. University of Illinois Press. * Pelletier, Alain (2010). ''Boeing: The Complete Story'', Haynes Publishing: Sparkford, Somerset, UK * Rice, Rondall Ravon (2004). ''The Politics of Air Power: From Confrontation to Cooperation in Army Aviation Civil-Military Relations'', University of Nebraska Press. * Russell, David Lee (2013). ''Eastern Air Lines: A History, 1926-1991'', McFarland & Co., Inc. * Serling, Robert J., (1976). "The Only Way To Fly". Doubleday & Company, Garden City, New York. . * Shiner, John F. (1983)

''Foulois and the Army Air Corps 1931-1935''

USAF Office of Air Force History, Washington, D.C. * Tate, Dr. James P. (1998). ''The Army and Its Air Corps: Army Policy Towards Aviation, 1919–1941'', Air University Press, Maxwell AFB, Alabama. * Van der Linden, F. Robert (2002). ''Airlines and Air Mail: The Post Office and Birth of the Commercial Aviation Industry.'' University of Kentucky Press. * Werrell, Kenneth P

"'Fiasco' revisited: the Air Corps & the 1934 air mail episode"

''Air Power History'', March 22, 2010. Reproduced by The Free Library * Winters, Kathleen C. (2010). ''Amelia Earhart: the Turbulent Life of an American Icon''. Palgrave-MacMillan. * Zuckerman, Michael A

"The Court of Congressional Contempt"

''Journal of Law and Politics'', Winter 2009, reproduced by ''The Wall Street Journal'' Law Blog. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

* ttp://www.oocities.org/capecanaveral/hangar/9496/ History of United Airlinesbr>Archived

2009-10-24) {{DEFAULTSORT:Air Mail Scandal Political scandals in the United States 20th-century aviation 20th-century military history of the United States United States military scandals United States Postal Service Airmail Postal history of the United States Corporate scandals Aviation history of the United States

Amelia Earhart

Amelia Mary Earhart ( , born July 24, 1897; disappeared July 2, 1937; declared dead January 5, 1939) was an American aviation pioneer and writer. Earhart was the first female aviator to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. She set many oth ...

also left T.A.T. at the same time, investing in the company, and Vidal appointed her as a vice-president. After Ludington failed to secure the mail contract, he resigned to take an appointment in the Aeronautics Branch within the Department of Commerce, becoming its director in September 1933 on Earhart's recommendation to FDR, a position he held when the scandal broke. In the summer of 1934 the Aeronautics Branch was renamed the Bureau of Air Commerce

The Air Commerce Act of 1926 created an Aeronautic Branch of the United States Department of Commerce. Its functions included testing and licensing of pilots, certification of aircraft and investigation of accidents.

In 1934, the Aeronautics Bran ...

. Earhart and Vidal were close friends from her hire at T.A.T. in 1929 until her disappearance in 1937, and were the object of frequent speculation that they were lovers. (Winters, p. 146)

Lewis did not think much about the conversation until he later read the Post Office Department's announcement that had awarded Ludington's arch-rival the CAM 25 air mail route contract at 89 cents a mile as measured against Ludington's extremely low bid. By February 1933 Ludington was virtually bankrupt and sold out to EAT for a "bottom basement price of $260,000." Lewis sensed there was a story to be written. He brought the story to the attention of William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

and, although Hearst would not print it, was given approval to investigate the story full-time.Brown testified to the Black Committee that the CAM 25 decision was based on Eastern's scheduling the entire route to Miami, Florida

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a East Coast of the United States, coastal metropolis and the County seat, county seat of Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade C ...

, while Ludington planned to use only the New York-Washington leg.

Lewis' investigation began to develop into an air mail contract scandal. Lewis was having difficulty impressing his findings on government officials until he approached Alabama Senator Hugo Black

Hugo Lafayette Black (February 27, 1886 – September 25, 1971) was an American lawyer, politician, and jurist who served as a U.S. Senator from Alabama from 1927 to 1937 and as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1937 to 1971. A ...

. Black was the chairman of a special committee established to investigate ocean mail contracts awarded by the federal government to the merchant marine. Interstate Commerce Commission

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) was a regulatory agency in the United States created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The agency's original purpose was to regulate railroads (and later trucking) to ensure fair rates, to eliminat ...

investigators seized records from all the mail carriers on September 28, 1933,Investigator Andrew G. Patterson, a former Alabama sheriff, was delegated to assist the special committee and led the seizures. He was a staunch progressive Democrat and an anti-monopolist who viewed air mail as frivolous and subsidies a waste of taxpayer money, and could see no correlation between it and transporting passengers. (Van der Linden, p. 177) and brought about public awareness of what became known as "the Black Committee".The committee was officially "The Special Committee to Investigate Air-Mail and Ocean-Mail Contracts, United States Senate, 73rd Congress, 2nd Session". The special Senate committee investigated alleged improprieties and gaming of the rate structure, such as carriers padlocking individual pieces of mail to increase weight. Despite showing that Brown's administration of the air mail had increased the efficiency of the service and lowered its costs from $1.10 to $0.54 per mile, and the obvious partisan politics involved in investigating what appeared to be a Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

scandal involving Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

by a Democratic-controlled committee, the hearings raised serious questions regarding its legality and ethics.

Black announced that he had found evidence of "fraud and collusion" between the Hoover Administration and the airlines and held public hearings in January 1934, although these allegations were later found to be without basis.Pelletier (2010), p. 47 Near the end of the hearings on the last day of January, MacCracken was subpoenaed to testify ''duces tecum

A ''subpoena duces tecum'' (pronounced in English ), or subpoena for production of evidence, is a court summons ordering the recipient to appear before the court and produce documents or other tangible evidence for use at a hearing or trial. In ...

'' "instanter" and appeared, but refused to produce files, citing attorney-client privilege unless the clients waived the privilege (which all did within a week of his appearance). However, the next day MacCracken's law partner gave Northwest Airways

Northwest Airlines Corp. (NWA) was a major American airline founded in 1926 and absorbed into Delta Air Lines, Inc. by a merger. The merger, approved on October 29, 2008, made Delta the largest airline in the world until the American Airlines- ...

vice president Lewis H. Brittin permission to go into MacCracken's files to remove a memo that Brittin claimed was personal and unrelated to the investigation. Brittin later tore up the memo and discarded it. Black charged MacCracken with Contempt of Congress

Contempt of Congress is the act of obstructing the work of the United States Congress or one of its committees. Historically, the bribery of a U.S. senator or U.S. representative was considered contempt of Congress. In modern times, contempt of Co ...

on February 5 and ordered him arrested.Decision, ''Jurney v. MacCracken''Justia.com. Retrieved 2016-02-09 During a five-day trial the Senate deemed him a

lobbyist

In politics, lobbying, persuasion or interest representation is the act of lawfully attempting to influence the actions, policies, or decisions of government officials, most often legislators or members of regulatory agencies. Lobbying, which ...

not protected by lawyer-client privilege and voted to convict him.Black and MacCracken were close personal friends. In addition to charging MacCracken with contempt, Black also named Brittin along with two officials of Western Air Express, president Harris M. Hanshue and his secretary Gilbert L. Givvin, who had also removed files. MacCracken and Brittin were convicted for "destroying evidence" (the memo in question contained no evidence of fraud or criminal collusion but was personally embarrassing to Brittin) and sentenced to ten days in jail. The WAE officers were acquitted because they returned their files intact to MacCracken. Brittin served his ten days without appeal but MacCracken filed a writ of habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

against his arrest which led to the historic case Jurney v. MacCracken

''Jurney v. MacCracken'', 294 U.S. 125 (1935), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that Congress has an implicit power to find one in contempt of Congress.. During a Senate investigation of airlines and of the United Sta ...

(Chesley E. Jurney was the Senate sergeant-at-arms, and also a friend of MacCracken's) in which the U.S. Supreme Court denied the writ. MacCracken served ten days in jail and was the last citizen arrested for "inherent" contempt of Congress over an 80-year period. (Zuckerman, "The Court of Congressional Contempt", Introduction)

Disregarding as Black did the fact that all but two of the existing contracts (the controversial transcontinental mail routes CAM 33 and CAM 34) had been awarded to the low bidder by Postmaster General Harry S. New

Harry Stewart New (December 31, 1858 – May 9, 1937) was a U.S. politician, journalist, and Spanish–American War veteran. He served as Chairman of the Republican National Committee, a United States senator from Indiana, and United States P ...

during the Coolidge Administration

Calvin Coolidge's tenure as the 30th president of the United States began on August 2, 1923, when Coolidge became president upon Warren G. Harding's death, and ended on March 4, 1929. A Republican from Massachusetts, Coolidge had been vice presi ...

, on February 7, 1934, Roosevelt's postmaster general, James A. Farley, announced that he and President Roosevelt were committed to protecting the public interest and that as a result of the investigation, President Roosevelt had ordered the cancellation of all domestic air mail contracts. However, not stated to the public was that the decision had overridden Farley's recommendation that it be delayed until June 1, by which time new bids could have been received and processed for continued civilian mail transport.

Use of the Army Air Corps

Executive Order 6591

Without consulting either Army Chief of Staff

Without consulting either Army Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was C ...

or Chief of the Air Corps Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Benjamin Foulois

Benjamin Delahauf Foulois (December 9, 1879 – April 25, 1967) was a United States Army general who learned to fly the first military planes purchased from the Wright brothers. He became the first military aviator as an airship pilot, and achi ...

, Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

George H. Dern at a cabinet meeting on the morning of February 9, 1934, assured President Roosevelt that the Air Corps could deliver the mail. That same morning, shortly after conclusion of the cabinet meeting, second assistant postmaster general Harllee Branch called Foulois to his office. A conference between members of the Air Corps, the Post Office, and the Aeronautics Branch

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is the largest transportation agency of the U.S. government and regulates all aspects of civil aviation in the country as well as over surrounding international waters. Its powers include air traffic m ...

of the Commerce Department

The United States Department of Commerce is an executive department of the U.S. federal government concerned with creating the conditions for economic growth and opportunity. Among its tasks are gathering economic and demographic data for busin ...

ensued in which Foulois, asked if the Air Corps could deliver the mail in winter, casually assured Branch that the Air Corps could be ready in a week or ten days.

At 4 o'clock that afternoon President Roosevelt suspended the airmail contracts effective at midnight February 19. He issued Executive Order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of th ...

6591 ordering the War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

* Dep ...

to place at the disposal of the Postmaster General "such air airplanes, landing fields, pilots and other employees and equipment of the Army of the United States needed or required for the transportation of mail during the present emergency, by air over routes and schedules prescribed by the Postmaster General."Congress enacted legislation on March 27, 1934 (48 Stat. 508) effective for one year and authorizing the Postmaster General to fund the operation from his appropriations, providing benefits to Army personnel killed or injured during the operation, and including Reserve officers called up for the operation as active duty members retroactive to February 10, 1934.

Preparation and plans

In 1933 the airlines carried several million pounds of mail on 26 routes covering almost of airways. Transported mostly by night, the mail was carried in modern passenger planes equipped with modern flight instruments and radios, using ground-based beam transmitters as navigation aids. The airlines had a well-established system of maintenance facilities along their routes. Initial plans were made for coverage of 18 mail routes totalling nearly ; and 62 flights daily, 38 by night. On February 14, five days before the Air Corps was to begin, General Foulois appeared before theHouse of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

Post Office Committee outlining the steps taken by the Air Corps in preparation. In his testimony he assured the committee that the Air Corps had selected its most experienced pilots and that it had the requisite experience at flying at night and in bad weather.

In actuality, of the 262 pilots eventually used, 140 were Reserve junior officers with less than two years flying experience. Most were second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

s and only one held a rank higher than first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a s ...

.Major Charles B. Oldfield, a regional commander in the Western Zone. The Air Corps had made a decision not to draw from its training schools, where most of its experienced pilots were assigned. Only 48 of those selected had logged at least 25 hours of flight time in bad weather, only 31 had 50 hours or more of night flying, and only 2 had 50 hours of instrument time.

Directional gyro

The heading indicator (HI), also known as a directional gyro (DG) or direction indicator (DI), is a flight instrument used in an aircraft to inform the aviator, pilot of the aircraft's aircraft heading, heading.

Use

The primary means of estab ...

s and 460 Artificial horizon

The attitude indicator (AI), formerly known as the gyro horizon or artificial horizon, is a flight instrument that informs the pilot of the aircraft orientation relative to Earth's horizon, and gives an immediate indication of the smallest orien ...

s, but very few of these were mounted in aircraft. It possessed 172 radio transceivers, almost all with a range of or less. Foulois eventually ordered the available equipment to be installed in the 122 aircraft assigned to the task, but the instruments were not readily available and Air Corps mechanics unfamiliar with the equipment sometimes installed them incorrectly or without regard for standardization of cockpit layout.

The project, termed AACMO (Army Air Corps Mail Operation), was placed under the supervision of Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Oscar Westover

Oscar M. Westover (July 23, 1883 – September 21, 1938) was a major general and fourth chief of the United States Army Air Corps.

Early life and career

Westover was born in Bay City, Michigan, and enlisted in the United States Army when he was ...

, assistant chief of the Air Corps. He created three geographic zones and appointed Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

Henry H. Arnold

Henry Harley Arnold (June 25, 1886 – January 15, 1950) was an American general officer holding the ranks of General of the Army and later, General of the Air Force. Arnold was an aviation pioneer, Chief of the Air Corps (1938–1941), ...

to command the Western Zone, Lieutenant Colonel Horace M. Hickam the Central Zone, and Major Byron Q. Jones

Byron Quinby Jones (April 9, 1888 – March 30, 1959) was a pioneer aviator and an officer in the United States Army. Jones began and ended his career as a cavalry officer, but for a quarter century between 1914 and 1939, he was an aviator in the ...

Jones had joined the Aviation Section, U.S. Signal Corps

The Aviation Section, Signal Corps, was the aerial warfare service of the United States from 1914 to 1918, and a direct statutory ancestor of the United States Air Force. It absorbed and replaced the Aeronautical Division, Signal Corps, and con ...

in 1914 but was becoming disenchanted with the Air Corps. In 1939 he would transfer back to the Cavalry. the Eastern Zone. Personnel and planes were immediately deployed, but problems began immediately with a lack of proper facilities (and in some instances, no facilities at all) for maintenance of aircraft and quartering of enlisted men, and a failure of tools to arrive where needed.Nalty (1997), p. 122.

Sixty Air Corps pilots took oaths as postal employees in preparation for the service and began training. On February 16, three pilots on familiarization flights were killed in crashes attributed to bad weather.2nd Lts Jean D. Grenier and Edwin D. White crashed their A-12 into Weber Canyon

Weber Canyon is a canyon in the Wasatch Range near Ogden, Utah, through which the Weber River flows west toward the Great Salt Lake. It is fed by 13 tributary creeks and is long.

History

Weber Canyon is, historically, one of the more importa ...

, Utah, and 1st Lt. James Y. Eastham crashed short of the runway at Jerome, Idaho

Jerome is a city in and county seat of Jerome County, Idaho, United States. The population was 10,890 at the 2010 census, up from 7,780 in 2000.Douglas Y1B-7

The Douglas Y1B-7 was a 1930s American bomber aircraft. It was the first US monoplane given the ''B-'' 'bomber' designation. The monoplane was more practical and less expensive than the biplane, and the United States Army Air Corps chose to expe ...

bomber. This presaged some of the worst and most persistent late winter weather in history.

Further attention was drawn to the startup when the airlines delivered a "parting shot" in the form of a publicity stunt to remind the public of its efficiency in mail service. World War I legend Eddie Rickenbacker

Edward Vernon Rickenbacker or Eddie Rickenbacker (October 8, 1890 – July 23, 1973) was an American fighter pilot in World War I and a Medal of Honor recipient.North American Aviation

North American Aviation (NAA) was a major American aerospace manufacturer that designed and built several notable aircraft and spacecraft. Its products included: the T-6 Texan trainer, the P-51 Mustang fighter, the B-25 Mitchell bomber, the F ...

(Eastern Air Transport's parent holding company

A holding company is a company whose primary business is holding a controlling interest in the securities of other companies. A holding company usually does not produce goods or services itself. Its purpose is to own shares of other companies ...

) and Jack Frye

William John "Jack" Frye (March 18, 1904 - February 3, 1959) was an aviation pioneer in the airline industry. Frye founded Standard Air Lines which eventually took him into a merger with Trans World Airlines (TWA) where he became president. Frye ...

of Transcontinental and Western Air, both of which had lost their mail contracts, flew T&WA's prototype Douglas DC-1 airliner "City of Los Angeles," which was still in flight test

Flight testing is a branch of aeronautical engineering that develops specialist equipment required for testing aircraft behaviour and systems. Instrumentation systems are developed using proprietary transducers and data acquisition systems. D ...

, across the country on the last evening before the Air Corps operation began. Carrying a partial load of mail and a passenger list of airlines officials and news reporters, they flew from Douglas Aviation's plant at Burbank, California

Burbank is a city in the southeastern end of the San Fernando Valley in Los Angeles County, California, United States. Located northwest of downtown Los Angeles, Burbank has a population of 107,337. The city was named after David Burbank, w ...

, to Newark, New Jersey. Bypassing several regular stops to stay ahead of a blizzard

A blizzard is a severe snowstorm characterized by strong sustained winds and low visibility, lasting for a prolonged period of time—typically at least three or four hours. A ground blizzard is a weather condition where snow is not falling b ...

, the stunt established a new cross-country time record of just over 13 hours, breaking the old record by more than five hours. The DC-1 arrived on the morning of February 19 only two hours before the Air Corps was forced by the winter weather to cancel the startup of AACMO.Werrell, Kenneth P"'Fiasco' revisited: the Air Corps & the 1934 air mail episode"

''Air Power History'', March 22, 2010. Reproduced by The Free Library, thefreelibary.com. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

AACMO

Blizzard conditions

On February 19, the blizzard disrupted the initial day's operations east of the

On February 19, the blizzard disrupted the initial day's operations east of the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

, where the scheduled first flight of the operation from Newark was cancelled. AACMO's actual first effort left from Kansas City, Missouri

Kansas City (abbreviated KC or KCMO) is the largest city in Missouri by population and area. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 508,090 in 2020, making it the 36th most-populous city in the United States. It is the central ...

, carrying 39 pounds of mail to St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

. Kenneth Werrell noted of the first flight out of Cleveland: "The pilot on the first air mail flight needed three tries and three aircraft to get aloft. Ten minutes later, he returned with a failed gyro compass and cockpit lights, and obtained a flashlight to read the instruments." Snow, rain, fog, and turbulent winds hampered flying operations for the remainder of the month over much of the United States. The route from Cleveland to Newark over the Allegheny Mountains

The Allegheny Mountain Range (; also spelled Alleghany or Allegany), informally the Alleghenies, is part of the vast Appalachian Mountain Range of the Eastern United States and Canada and posed a significant barrier to land travel in less devel ...

was dubbed "Hell's Stretch" by airmail pilots.

In the Western Zone, Arnold established his headquarters in

In the Western Zone, Arnold established his headquarters in Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the Capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Utah, most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the county seat, seat of Salt Lake County, Utah, Sal ...

. In the winter of 1932–1933, he and many of his pilots had gained winter flying experience flying food-drop missions to aid Indian reservation

An Indian reservation is an area of land held and governed by a federally recognized Native American tribal nation whose government is accountable to the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs and not to the state government in which it ...

settlements throughout the American Southwest isolated by blizzards. As a result of this experience and direct supervision, Arnold's zone was the only one in which a pilot was not killed.

The Western Zone's first flights were made using 18 Boeing P-12

The Boeing P-12/F4B was an American pursuit aircraft that was operated by the United States Army Air Corps , United States Marine Corps, and United States Navy.

Design and development

Developed as a private venture to replace the Boeing F2B an ...

fighters, but these could carry a maximum of only 50 pounds of mail each, and even that amount made them tail-heavy. After one week they were replaced by Douglas O-38

The Douglas O-38 was an observation airplane used by the United States Army Air Corps.

Between 1931 and 1934, Douglas built 156 O-38s for the Air Corps, eight of which were O-38Fs. Some were still in service at the time of the Pearl Harbor Attack ...

variants including the Douglas O-35 and its bomber version, the B-7, and Douglas O-2

The Douglas O-2 was a 1920s American observation aircraft built by the Douglas Aircraft Company.

Development

The important family of Douglas observation aircraft sprang from two XO-2 prototypes, the first of which was powered by the 420 hp ...

5C observation biplanes borrowed from the National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

. In both the Western and Eastern zones, these became the aircraft of choice, modified to carry 160 pounds of mail in their rear cockpits, and in their nose (bombardier/navigator) compartments where those existed. Better-suited planes such as the new Martin YB-10 bomber and Curtiss A-12 Shrike

The Curtiss A-12 Shrike was the United States Army Air Corps' second monoplane ground-attack aircraft, and its main attack aircraft through most of the 1930s. It was based on the Curtiss A-8 Shrike, A-8, but had a radial engine instead of the A ...

ground attack aircraft were in insufficient numbers to be of practical use. Two YB-10s crashlanded when pilots forgot to lower its retractable landing gear, and there were only enough A-12s for a partial squadron in the Central Zone.Major Oldfield was one of the two pilots, at Cheyenne on April 23. Despite the accident, the next year he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and assigned command of the 2nd Bomb Group.

On February 22 a young pilot departing Chicago in an O-39 flew into a snow storm over

On February 22 a young pilot departing Chicago in an O-39 flew into a snow storm over Deshler, Ohio

Deshler is a village in Henry County, Ohio, United States. The population was 1,799 at the 2010 census.

History

Deshler was platted in 1873, and named for John G. Deshler, the original owner of the town site. A post office has been in operatio ...

, and became lost after his navigational radio failed. Fifty miles off course, he bailed out but his parachute caught on the tail section of his airplane and he was killed. That same day in Denison, Texas

Denison is a city in Grayson County, Texas, Grayson County, Texas, United States. It is south of the Texas–Oklahoma border. The population was 22,682 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census. Denison is part of the Texoma region and is one ...

, another pilot attempting a forced landing was killed when his P-26A flipped over on soft turf. The next day, a Douglas C-29 Dolphin took off from Floyd Bennett Field

Floyd Bennett Field is an airfield in the Marine Park neighborhood of southeast Brooklyn in New York City, along the shore of Jamaica Bay. The airport originally hosted commercial and general aviation traffic before being used as a naval air ...

, New York on a flight to Langley Field Langley may refer to:

People

* Langley (surname), a common English surname, including a list of notable people with the name

* Dawn Langley Simmons (1922–2000), English author and biographer

* Elizabeth Langley (born 1933), Canadian perform ...

to ferry a mail aircraft and ditched when both engines failed a mile off of Rockaway Beach. Waiting for a rescue attempt in heavy seas, the passenger on the amphibian drowned.2nd Lt. Durwood O. Lowry died in Ohio, 2nd Lt. Fred I. Patrick in Texas, and 2nd Lt. George P. McDermott in New York.

President Roosevelt, publicly embarrassed, ordered a meeting with Foulois that resulted in a reduction of routes and schedules (which were already only 60% of that flown by the airlines), and strict flight safety rules. Among the new rules were restrictions on night flying: forbidding pilots with less than two years' experience from being scheduled except under clear conditions, prohibiting takeoffs in inclement weather, and requiring fully functional instruments and radio to continue on in poor conditions. Control officers on the ground were made responsible for enforcement of the restrictions in their areas.

Suspension of the operation

On March 8 and 9, 1934, four more pilots died in crashes,Lts. Frank L. Howard and Arthur R. Kerwin, Jr. in the crash of an O-38E at

On March 8 and 9, 1934, four more pilots died in crashes,Lts. Frank L. Howard and Arthur R. Kerwin, Jr. in the crash of an O-38E at Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the Capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Utah, most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the county seat, seat of Salt Lake County, Utah, Sal ...

, Lt. Otto Weineke in an O-39 at Burton, Ohio

Burton is a village in Geauga County, Ohio, United States. The population was 1,452 at the 2010 census.

Burton is the location of Century Village, run by the Geauga Historical Society. The museum village is composed of 19th-century buildings mo ...

, and Pvt. Ernest B. Sell, a flight engineer on a Keystone B-6

The Keystone B-6 was a biplane bomber developed by the Keystone Aircraft company for the United States Army Air Corps.

Design and development

In 1931, the United States Army Air Corps received five working models (Y1B-6s) of the B-6 bomber. The ...

in a cyprus swamp near Daytona Beach, Florida

Daytona Beach, or simply Daytona, is a coastal Resort town, resort-city in east-central Florida. Located on the eastern edge of Volusia County, Florida, Volusia County near the East Coast of the United States, Atlantic coastline, its population ...

. Sell's death occurred during a crash-landing while he was using a hand pump to transfer fuel from a full tank to an empty one during a fuel line malfunction. (Tate, p. 132) totaling ten fatalities in less than one million miles of flying the mail. (Ironically, the crash of an American Airlines airliner on March 9, also killing four, went virtually unnoticed in the press.) Rickenbacker was quoted as calling the program "legalized murder", which became a catchphrase

A catchphrase (alternatively spelled catch phrase) is a phrase or expression recognized by its repeated utterance. Such phrases often originate in popular culture and in the arts, and typically spread through word of mouth and a variety of mass ...

for criticism of the Roosevelt administration's handling of the crisis. Aviation icon and former air mail pilot Charles A. Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

stated in a telegram to Secretary of War Dern that using the Air Corps to carry mail was "unwarranted and contrary to American principles." Even though both had close ties to the airline industry, their criticisms seriously stung the Roosevelt Administration.Lindbergh was a salaried consultant and stockholder to both TWA and Pan American Airways

Pan American World Airways, originally founded as Pan American Airways and commonly known as Pan Am, was an American airline that was the principal and largest international air carrier and unofficial overseas flag carrier of the United States ...

. His telegram to Dern was made public by ''Newsweek Magazine''. Sources: Tate 1998, p. 133 ("legalized murder"), p. 144 (Lindbergh), p. 155 (''Newsweek'').

On March 10, President Roosevelt called Foulois and Army Chief of Staff General Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was C ...

to the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

, asking them to fly only in completely safe conditions. Foulois replied that to ensure complete safety the Air Corps would have to end the flights, and Roosevelt suspended airmail service on March 11, 1934. Foulois wrote in his autobiography that he and MacArthur incurred "the worst tongue-lashing I ever received in all my military service". Norman E. Borden, in ''Air Mail Emergency of 1934'', wrote: "To lessen the attacks on Roosevelt and Farley, Democratic leaders in both houses of Congress and Post Office officials placed the blame for all that had gone wrong on the shoulders of Foulois." Other supporters of the president outside of the government muted criticism of the administration by focusing on and excoriating Lindbergh, who had also made headlines by publicly protesting the cancellation of the contracts two days after they were announced, "as if his telegram had caused the deaths."

Despite an 11th fatality from a training crash in Wyoming on March 17,2nd Lt. Harold G. Richardson died when his O-38E spun in at low altitude. A recent co-pilot with United Airlines, Richardson was a Reservist called to active duty after being laid-off because of the mail contracts cancellations. the Army resumed the program again on March 19, 1934, in better weather, using only nine routes,These routes were Chicago-New York, Chicago-San Francisco, Chicago-Dallas, Salt Lake City-San Diego, Salt Lake City-Seattle, Cheyenne-Denver, New York-Boston, New York-Atlanta, and Atlanta-Jacksonville. limited schedules, and hurried improvements in instrument flying.The prevailing attitude among Air Corps senior leadership was that reliance on instruments made for weak pilots, leading to a neglect of training and lack of experience. That attitude had begun to change with the introduction of training to create instrument instructors, but the second such class was only halfway through its 6-week course when AACMO began. The week's suspension availed the Air Corps an opportunity to install instruments and familiarize pilots with their use. Both were hastily accomplished, however, with nonstandard and often questionable results. (Werrell) The O-38E, which had been involved in two fatal accidents at Cheyenne, Wyoming

Cheyenne ( or ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Wyoming, as well as the county seat of Laramie County, with 65,132 residents, per the 2020 US Census. It is the principal city of the Cheyenne metropolitan statistical ...

, was withdrawn completely from the operation despite its enclosed cockpit because of its propensity to go into an unrecoverable spin in the mountainous terrain.The O-38E was not designed to carry extra equipment or loads, and so used its small baggage compartment and rear cockpit to transport mail. The aircraft was difficult to hold level at higher altitude, causing it to whipstall (an unintentional tailslide

The tailslide is an aerobatic maneuver that starts from level flight with a 1/4 loop up into a straight vertical climb (at full power) until the aircraft loses momentum. When the aircraft's speed reaches zero and it stops climbing, the pilot maint ...

), and the improperly distributed weight quickly brought about a spin that needed a minimum of 2000 feet to recover. In early April the Air Corps removed all pilots with less than two years' experience from the operation.

The Air Corps began drawing down AACMO on May 8, 1934, when temporary contracts with private carriers were put into effect.The temporary contracts were awarded on April 20 by Postmaster General Farley, under the Air Mail Act of 1930, at a meeting with invited carriers only that critics found not unlike the "spoils conference" that began the controversy. (Van der Linden, p. 284; Duffy, pp. 39-40) On AACMO's last night of coast-to-coast service on May 7–8, YB-10s were used on four of the six legs from Oakland, California

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast of the United States, West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third ...