Africa–United States Relations on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The United States has political, economic and cultural ties with the independent African countries.

U.S.-Ethiopian relations were established in 1903, after meetings in Ethiopia between Emperor

U.S.-Ethiopian relations were established in 1903, after meetings in Ethiopia between Emperor

online

* Banks, John P., et al. "Top five reasons why Africa should be a priority for the United States." (Brookings, 2013

online

* Butler, L. J. "Britain, the United States, and the demise of the Central African Federation, 1959–63." ''Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History'' 28.3 (2000): 131–151. * Chester, Edward W. ''Clash of Titans: Africa and US Foreign Policy'' (Orbis Books, 1974

online review

* Damis, John. "The United States and North Africa." in ''Polity And Society In Contemporary North Africa'' (Routledge, 2019). 221–240. * Devermont, Judd. "World is Coming to Sub-Saharan Africa. Where is the United States?" (Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), 2018

online

* Duignan, P., and L. H. Gann. ''The United States and Africa: A History'' (Cambridge University Press, 1984

online

* Gordon, David F. et al. eds. ''The United States and Africa : a post-Cold War perspective'' (1998

online

* Kraxberger, Brennan M. "The United States and Africa: shifting geopolitics in an" Age of Terror"." ''Africa Today'' (2005): 47-6

online

* Meriwether, James Hunter. ''Tears, Fire, and Blood: The United States and the Decolonization of Africa'' (University of North Carolina Press, 2021)

online review

* Rosenberg, Emily S. "The Invisible Protectorate: The United States, Liberia, and the Evolution of Neocolonialism, 1909–40." ''Diplomatic History'' (1985) 9#3 pp 191–214. * Schraeder, Peter J. ''United States foreign policy toward Africa: Incrementalism, crisis and change'' (Cambridge UP, 1994). * Shinn, David H. "Africa: the United States and China court the continent." ''Journal of International Affairs'' 62.2 (2009): 37-5

online

* Yohannes, Okbazghi. ''The United States and the Horn of Africa: an analytical study of pattern and process'' (Routledge, 2019). * Zimmerman, Andrew. ''Alabama in Africa: Booker T. Washington, the German empire, and the globalization of the New South'' (Princeton UP, 2010). {{DEFAULTSORT:Africa-United States relations

Pre-1940

BeforeWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the United States dealt directly only with the former American colony of Liberia, the independent nation of Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

, the independent nation of Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

, and the semi-independent nation of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

.

Liberia

U.S. relations with Liberia date back to 1819, when the Congress appropriated $100,000 for the establishment of Liberia. The settlers were free blacks or freed slaves who were selected and funded by theAmerican Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America until 1837, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the migration of freebor ...

(ACS). The religious ethos and cultural norms of the ACS shaped Afro-American settler society and determined social behavior in 19th-century Liberia. The Methodist Episcopal Church

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself on a national basis. In ...

sent black ministers as missionaries to Liberia. Although they could identify with the local population on a purely racial basis, the nature of their religious indoctrination caused them to view the Liberians as inferiors whose souls needed saving.

Under Republican President Abraham Lincoln, The United States officially recognized Liberia in 1862, 15 years after its establishment as a sovereign nation, and the two nations shared very close diplomatic, economic, and military ties until the 1990s.

The United States had a long history of intervening in Liberia's internal affairs, occasionally sending naval vessels to help the Americo-Liberians, who comprised the ruling minority, put down insurrections by indigenous tribes (in 1821, 1843, 1876, 1910, and 1915). By 1909, Liberia faced serious external threats to its sovereignty from the European colonial powers over unpaid foreign loans and annexation of its borderlands.

President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

devoted a portion of his First Annual Message to Congress (December 7, 1909) to the Liberian question, noting the close historical ties between the two countries that gave an opening for a wider intervention:

:"It will be remembered that the interest of the United States in the Republic of Liberia springs from the historical fact of the foundation of the Republic by the colonization of American citizens of the African race. In an early treaty with Liberia there is a provision under which the United States may be called upon for advice or assistance. Pursuant to this provision and in the spirit of the moral relationship of the United States to Liberia, that Republic last year asked this Government to lend assistance in the solution of certain of their national problems, and hence the Commission was sent across the ocean on two cruisers.

In 1912 the U.S. arranged a 40-year international loan of $1.7 million, against which Liberia had to agree to four Western powers (America, Britain, France and Germany) controlling Liberian Government revenues for the next 14 years, until 1926. American administration of the border police also stabilized the frontier with Sierra Leone and checked French ambitions to annex more Liberian territory. The American navy also established a coaling station in Liberia, cementing its presence. When World War I started, Liberia declared war on Germany and expelled its resident German merchants, who constituted the country's largest investors and trading partners – Liberia suffered economically as a result.

In the largest American private investment in Africa, in 1926, the Liberian government gave a concession to the American rubber company Firestone to start the world's largest rubber plantation at Harbel

Harbel is a town in Margibi County, Liberia. It lies along the Farmington River, about 15 miles upstream from the Atlantic Ocean.

, Liberia. At the same time, Firestone arranged a $5 million private loan to Liberia.

In the 1930s Liberia was again virtually bankrupt, and, after some American pressure, agreed to an assistance plan from the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. As part of this plan, two key officials of the League were placed in positions to ´advise´ the Liberian government.

Ethiopia

U.S.-Ethiopian relations were established in 1903, after meetings in Ethiopia between Emperor

U.S.-Ethiopian relations were established in 1903, after meetings in Ethiopia between Emperor Menelik II

, spoken = ; ''djānhoi'', lit. ''"O steemedroyal"''

, alternative = ; ''getochu'', lit. ''"Our master"'' (pl.)

Menelik II ( gez, ዳግማዊ ምኒልክ ; horse name Abba Dagnew (Amharic: አባ ዳኘው ''abba daññäw''); 17 A ...

and an emissary of President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

. This first step was augmented with treaties of arbitration and conciliation signed at Addis Ababa 26 January 1929. These formal relations included a grant of Most Favored Nation status, and were good up to the Italian occupation in 1935.

Italy invaded and conquered Ethiopia 1935, and evaded League of Nations sanctions. The United States was one of only five countries which refused to recognize the Italian conquest. During World War II, British forces expel the Italians and restored independence to Ethiopia. In January 1944, when President Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

met personally with Emperor Haile Selassie in Egypt. The meeting both strengthened the Emperor's already strong predilection towards the United States, as well as discomforted the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

who had been at odds with the Ethiopian government over the disposition of Eritrea

Eritrea ( ; ti, ኤርትራ, Ertra, ; ar, إرتريا, ʾIritriyā), officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of Eastern Africa, with its capital and largest city at Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia ...

and the Ogaden

Ogaden (pronounced and often spelled ''Ogadēn''; so, Ogaadeen, am, ውጋዴ/ውጋዴን) is one of the historical names given to the modern Somali Region, the territory comprising the eastern portion of Ethiopia formerly part of the Harargh ...

.

In the 1950s, Ethiopia became a minor player in the Cold War after signing a series of treaties with the United States, and receiving $282 million in military assistance and $366 million in economic assistance in agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people to ...

, education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty. Va ...

, public health, and transportation

Transport (in British English), or transportation (in American English), is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land (rail and road), water, cable, pipeline, ...

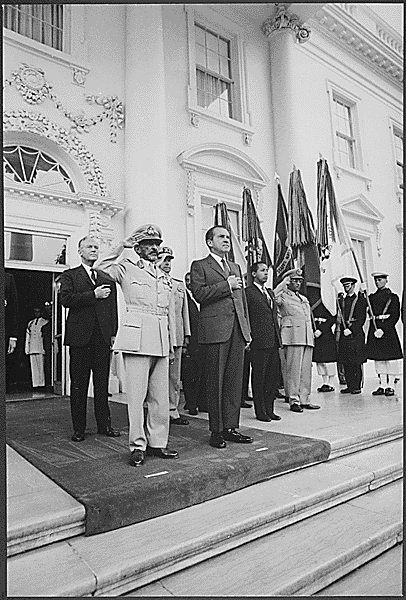

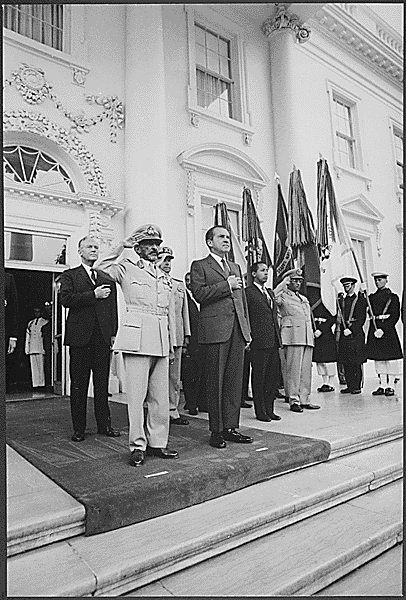

. In 1957, Vice President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

visited Ethiopia and called it "one of the United States' most stalwart and consistent allies".

The economic aid came through Washington's "Point Four" program and served as a model for American assistance to the newly independent African nations. The original goal of "Point Four" was containing the spread of communism, which was not a major threat in Africa in the 1950s. More broadly it served as a political project to convince Africans that it was to their long-term interest to side with the West. The program sought to improve social and economic conditions without interfering with existing political or social order.

Morocco

Relations between Morocco the United States date back to the 18th century. On December 20, 1777, the Kingdom of Morocco became the first country in the world to recognize United States independence, only a year and a half after the U.S. Declaration of Independence was issued.Egypt

Trade and cultural relations date back to the late 19th century. the Presbyterians and other Protestant organizations sponsored large-scale missionary activity. Small numbers of Egyptians converted to Christianity. Influential circles in the United States gained an increased awareness of the social and economic conditions in Egypt. One major impact was bringing modern educational methods to Egypt, which the local officials and British had largely ignored. The flagship institution was theAmerican University in Cairo

The American University in Cairo (AUC; ar, الجامعة الأمريكية بالقاهرة, Al-Jāmi‘a al-’Amrīkiyya bi-l-Qāhira) is a private research university in Cairo, Egypt. The university offers American-style learning programs ...

, which offered all classes in Arabic, and practiced flexible methods that were adopted in Egyptian-sponsored schools when they began to appear in the 20th century.

Official Modern relations were established in 1922 when the United States recognized Egypt's independence from a protectorate status of the United Kingdom. Britain nevertheless controlled Egyptian foreign affairs, and the United States rarely had direct connections with the Egyptian government. In 1956, the U.S. was alarmed at the closer ties between Egypt and the Soviet Union, and prepared the OMEGA Memorandum The 'OMEGA' memorandum of March 28, 1956, was a secret United States informal policy memorandum drafted by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles for President Dwight D. Eisenhower. The goal was to reduce the influence in the Middle East of Egypt's ...

as a stick to reduce the regional power of President Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein, . (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian politician who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced far-re ...

.

When Egypt recognized Communist China, the U.S. ended talks about funding the Aswan Dam

The Aswan Dam, or more specifically since the 1960s, the Aswan High Dam, is one of the world's largest embankment dams, which was built across the Nile in Aswan, Egypt, between 1960 and 1970. Its significance largely eclipsed the previous Aswan L ...

, a high prestige project much desired by Egypt. The dam was later built by the Soviet Union. When Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

in 1956, the Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

erupted with Britain and France invading to retake control of the canal. Using heavy diplomatic and economic pressure, the Eisenhower administration

Dwight D. Eisenhower's tenure as the 34th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1953, and ended on January 20, 1961. Eisenhower, a Republican from Kansas, took office following a landslide victory ov ...

forced Britain and France to withdraw soon. A major result was that the United States largely replaced Great Britain in terms of regional influence in the Middle East.

Others

Kingdom of Dahomey

In 1860, the '' Clotilda'' arrived in theKingdom of Dahomey

The Kingdom of Dahomey () was a West African kingdom located within present-day Benin that existed from approximately 1600 until 1904. Dahomey developed on the Abomey Plateau amongst the Fon people in the early 17th century and became a region ...

to illegally transport 110 slaves to the United States after the U.S. abolished the Atlantic slave trade in 1808 with the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves

The Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of 1807 (, enacted March 2, 1807) is a United States federal law that provided that no new slaves were permitted to be imported into the United States. It took effect on January 1, 1808, the earliest dat ...

, the last known slave ship to have carried slaves from Africa to the United States.

Writing in his journal in 1860, Captain William Foster of the ''Clotilda'' described how he came in possession of the enslaved Africans on his ship,

Togo

In 1901, theTuskegee Institute

Tuskegee University (Tuskegee or TU), formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute, is a private, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was founded on Independence Day in 1881 by the state legislature.

The campus was de ...

, a state college in Alabama directed by the national Black leader Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American c ...

, sent experts to the German colony of Togo in West Africa. The goal was to introduce modern agricultural technology in order to modernize the colony, basing its economy on cotton exports.

World War II

Vichy France controlled much of North Africa. with the British based in Egypt pushing back German and Italian forces, the United States and Britain launchedOperation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – Run for Tunis, 16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of secu ...

with amphibious landings in Morocco and Algeria in November 1942. After brief resistance, the Vichy French forces switch sides and began to collaborate with the Allies. After some delays, the eastern and western Allied forces met up in Tunisia, and forced the surrender the main German and Italian armies. The Americans then moved on to an invasion of Sicily and in southern Italy.

Numerous locations in Africa were used in moving supplies that were either flown in via Brazil or brought in by ship. supplies were transshipped across Africa and moved through Egypt to supply the Soviet Union.

Decolonization, 1951 to 1960

All the colonial powers engaged indecolonization

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on separatism, in ...

in the 1950s, starting with Libya 1951, Sudan, Morocco and Tunisia in 1956, and Ghana in 1957. In 1958 President Eisenhower's State Department created the Bureau of African Affairs under the Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs

The Assistant Secretary for the Bureau of African Affairs is the head of the Bureau of African Affairs, within the United States Department of State, who guides operation of the U.S. diplomatic establishment in the countries of sub-Saharan Afric ...

to deal with sub- Sahara Africa. Countries in North Africa were under the Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs. G. Mennen Williams

Gerhard Mennen "Soapy" Williams (February 23, 1911 – February 2, 1988) was an American politician who served as the List of governors of Michigan, 41st governor of Michigan, elected in 1948 and serving six two-year terms in office. He lat ...

, a former Democratic governor of Michigan, was the assistant secretary of state under President John F. Kennedy. Williams actively promoted and encouraged decolonization. The Kennedy administration launched the Peace Corps

The Peace Corps is an independent agency and program of the United States government that trains and deploys volunteers to provide international development assistance. It was established in March 1961 by an executive order of President John F. ...

, which sent thousands of young American volunteers to serve in local villages. The United States Agency for International Development

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is an independent agency of the U.S. federal government that is primarily responsible for administering civilian foreign aid and development assistance. With a budget of over $27 bi ...

(USAID) started providing cash economic assistance, and the Pentagon provided funds and munitions for local armies. Euphoria ended when the Congo Crisis

The Congo Crisis (french: Crise congolaise, link=no) was a period of political upheaval and conflict between 1960 and 1965 in the Republic of the Congo (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The crisis began almost immediately after ...

of the 1960s indicated very large scale instability.

Historian James Meriweather argues that American policy towards Africa was characterized by a middle road approach, which supported African independence but also reassured European colonial powers that their holdings could remain intact. Washington wanted the right type of African groups to lead newly independent states, which tended to be noncommunist and not especially democratic. Meriweather argues that nongovernmental organizations influenced American policy towards Africa. They pressured state governments and private institutions to disinvest from African nations not ruled by the majority population. These efforts also helped change American policy towards South Africa, as seen with the passage of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act

The Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 was a law enacted by the United States Congress. The law imposed sanctions against South Africa and stated five preconditions for lifting the sanctions that would essentially end the system of apart ...

of 1986.

Kennedy-Johnson, 1961-1969

Whereas Eisenhower had largely neglected Africa, President John F. Kennedy took an aggressive activist approach. Kennedy was alarmed by the implications of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev's 1961 speech that proclaimed the USSR's intention to intervene in anticolonial struggles around the world. Since most nations in Europe, Latin America, and Asia had already chosen sides, Kennedy and Krushchev both looked to Africa as the next Cold War battleground. Under the leadership ofSékou Touré

Sekou, also spelled Sékou or Seku, is a given name from the Fula language. It is equivalent to the Arabic ''Sheikh''. People with this name include:

Given name

* Seku Amadu (1776–1845), also known as Sékou Amadou or Sheikh Amadu, founder of th ...

, the former French colony of Guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

in West Africa proclaimed its independence in 1958 and immediately sought foreign aid.

Eisenhower was hostile to Touré, so the African nation quickly turned to the Soviet Union--making it the Kremlin's first success story in Africa. Kennedy and his Peace Corps director Sargent Shriver

Robert Sargent Shriver Jr. (November 9, 1915 – January 18, 2011) was an American diplomat, politician, and activist. As the husband of Eunice Kennedy Shriver, he was part of the Kennedy family. Shriver was the driving force behind the creation ...

tried even harder than Khrushchev. By 1963 Guinea had shifted away from Moscow into a closer friendship with Washington. Kennedy had a broad vision that encompassed all of Africa. He opened up the White House to receive eleven African heads of state in 1961, ten in 1962, and another seven in 1963.

Jimmy Carter: 1977-81

Historians are generally agreed that President Jimmy Carter, 1977–81, was not very successful when it came to Africa. However, there are multiple explanations available. The orthodox interpretation posits Carter as a dreamy star-eyed idealist. Revisionists said that did not matter nearly as much as the intense rivalry between dovish Secretary of StateCyrus Vance

Cyrus Roberts Vance Sr. (March 27, 1917January 12, 2002) was an American lawyer and United States Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter from 1977 to 1980. Prior to serving in that position, he was the United States Deputy Secretary of ...

and hawkish National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski

Zbigniew Kazimierz Brzeziński ( , ; March 28, 1928 – May 26, 2017), or Zbig, was a Polish-American diplomat and political scientist. He served as a counselor to President Lyndon B. Johnson from 1966 to 1968 and was President Jimmy Carter's ...

. Vance lost nearly all the battles, and finally resigned in disgust.

Meanwhile, there are now post-revisionist historians who blame his failures on his confused management style and his refusal to make tough decisions. Along post-revisionist lines, Nancy Mitchell in a monumental book depicts Carter as a decisive but ineffective Cold Warrior, who, nevertheless had some successes because Soviet incompetence was even worse.

Reagan-Bush administrations, 1981-1993

ThePresidency of Ronald Reagan

Ronald Reagan's tenure as the 40th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1981, and ended on January 20, 1989. Reagan, a Republican from California, took office following a landslide victory over D ...

, starting in January 1981, decided that the Carter administration had largely failed in Africa, and sharply changed directions. It abandoned the Carter emphasis on human rights, and instead emphasized anti-communism. This meant reversals of policies in South Africa and Angola, and changes in the USA's relationships with Ethiopia and Libya, which were pro-Soviet.

Carter's policy was to denounce and try to end the apartheid policies in South Africa and Angola, whereby small white minorities had full control of government. Under the new conservative administration a more conciliatory approach was taken by the Assistant Secretary of State Chester Crocker

Chester Arthur Crocker (born October 29, 1941) is an American diplomat and scholar who served as Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs from June 9, 1981, to April 21, 1989, in the Reagan administration. Crocker, architect of the U.S. p ...

. He rejected confrontational approaches, and called for "Constructive engagement". Crocker was highly critical of the outgoing Carter administration for its apparent hostility to the white minority government in South Africa, by acquiescing in the United Nations Security Council's imposition of a mandatory arms embargo ( UNSCR 418/77) and the UN's demand for the end of South Africa's illegal occupation of Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

( UNSCR 435/78).

Crocker came up with a complex multinational peace plan, that he struggled to achieve for eight years. The most essential provision required the removal of Cuba's large, well-armed forces from Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

. The United States would then quit funding the anti-Marxist forces led by Jonas Savimbi

Jonas Malheiro Savimbi (; 3 August 1934 – 22 February 2002) was an Angolan revolutionary politician and rebel military leader who founded and led the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA). UNITA waged a guerrilla war agai ...

, South Africa would pull out of Southwest Africa, allowing Namibia to become independent. The white rulers in South Africa would remain in power but relax their restrictions on the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a Social democracy, social-democratic political party in Republic of South Africa, South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when ...

. Crocker was successful in 1988, and during the George HW Bush administration, 1989 to 1993, the goals were realized.

The Reagan administration mobilized private philanthropic and business sources to fund food supplies to areas in Africa devastated by famine. For example, music promoter Bob Geldorf

Robert Frederick Zenon Geldof (; born 5 October 1951) is an Irish singer-songwriter, and political activist. He rose to prominence in the late 1970s as lead singer of the Rock music in Ireland, Irish rock band the Boomtown Rats, who achieved ...

in 1985 produced Live Aid

Live Aid was a multi-venue benefit concert held on Saturday 13 July 1985, as well as a music-based fundraising initiative. The original event was organised by Bob Geldof and Midge Ure to raise further funds for relief of the 1983–1985 fami ...

, a benefit concert that raised over $65 million and dramatically raised awareness. US government focused on transportation and administrative issues.

Recent history

Military

As of 2019 the U.S. military maintains a network of 29 military bases across the African continent.Diplomatic missions

* The African Union maintains a delegation with a resident Ambassador toWashington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

See also

*Africa–China relations

Sino-African relations or Afro-Chinese relations are the historical, political, economic, military, social, and cultural connection between mainland China and the African continent.

Little is known about ancient relations between China and A ...

* Africa–Soviet Union relations

* Africa–EU relations

* France–Africa relations

France–Africa relations cover a period of several centuries, starting around in the Middle Ages, and have been very influential to both regions.

First exchanges (8th century)

Following the invasion of Spain by the Berber people, Berber Comma ...

* France–Africa relations

France–Africa relations cover a period of several centuries, starting around in the Middle Ages, and have been very influential to both regions.

First exchanges (8th century)

Following the invasion of Spain by the Berber people, Berber Comma ...

* African immigration to the United States

African immigration to the United States refers to Immigration to the United States, immigrants to the United States who are or were nationals of modern African countries. The term ''African'' in the scope of this article refers to geographical ...

* United States Africa Command

The United States Africa Command (USAFRICOM, U.S. AFRICOM, and AFRICOM), is one of the eleven unified combatant commands of the United States Department of Defense, headquartered at Kelley Barracks, Stuttgart, Germany. It is responsible for U. ...

** List of United States military bases

This is a list of military installations owned or used by the United States Armed Forces currently located in the United States and around the world. This list details only current or recently closed facilities; some defunct facilities are f ...

Notes

Further reading

* Abramovici, Pierre, and Julie Stoker. "United States: the new scramble for Africa." ''Review of African Political Economy'' (2004): 685-69online

* Banks, John P., et al. "Top five reasons why Africa should be a priority for the United States." (Brookings, 2013

online

* Butler, L. J. "Britain, the United States, and the demise of the Central African Federation, 1959–63." ''Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History'' 28.3 (2000): 131–151. * Chester, Edward W. ''Clash of Titans: Africa and US Foreign Policy'' (Orbis Books, 1974

online review

* Damis, John. "The United States and North Africa." in ''Polity And Society In Contemporary North Africa'' (Routledge, 2019). 221–240. * Devermont, Judd. "World is Coming to Sub-Saharan Africa. Where is the United States?" (Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), 2018

online

* Duignan, P., and L. H. Gann. ''The United States and Africa: A History'' (Cambridge University Press, 1984

online

* Gordon, David F. et al. eds. ''The United States and Africa : a post-Cold War perspective'' (1998

online

* Kraxberger, Brennan M. "The United States and Africa: shifting geopolitics in an" Age of Terror"." ''Africa Today'' (2005): 47-6

online

* Meriwether, James Hunter. ''Tears, Fire, and Blood: The United States and the Decolonization of Africa'' (University of North Carolina Press, 2021)

online review

* Rosenberg, Emily S. "The Invisible Protectorate: The United States, Liberia, and the Evolution of Neocolonialism, 1909–40." ''Diplomatic History'' (1985) 9#3 pp 191–214. * Schraeder, Peter J. ''United States foreign policy toward Africa: Incrementalism, crisis and change'' (Cambridge UP, 1994). * Shinn, David H. "Africa: the United States and China court the continent." ''Journal of International Affairs'' 62.2 (2009): 37-5

online

* Yohannes, Okbazghi. ''The United States and the Horn of Africa: an analytical study of pattern and process'' (Routledge, 2019). * Zimmerman, Andrew. ''Alabama in Africa: Booker T. Washington, the German empire, and the globalization of the New South'' (Princeton UP, 2010). {{DEFAULTSORT:Africa-United States relations

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

Foreign relations of the United States