Aerial Photographic Reconnaissance on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Aerial reconnaissance is

Aerial reconnaissance is

After the invention of photography, primitive aerial photographs were made of the ground from manned and unmanned balloons, starting in the 1860s, and from tethered kites from the 1880s onwards. An example was

After the invention of photography, primitive aerial photographs were made of the ground from manned and unmanned balloons, starting in the 1860s, and from tethered kites from the 1880s onwards. An example was

The use of aerial photography rapidly matured during the

The use of aerial photography rapidly matured during the  The

The

During 1928, the

During 1928, the  Cotton and Longbottom proposed the use of

Cotton and Longbottom proposed the use of  Other

Other

The collection and interpretation of aerial reconnaissance intelligence became a considerable enterprise during the war. Beginning in 1941,

The collection and interpretation of aerial reconnaissance intelligence became a considerable enterprise during the war. Beginning in 1941,

/ref> The

During 1942 and 1943, the CIU gradually expanded and was involved in the planning stages of practically every operation of the war, and in every aspect of intelligence. In 1945, daily intake of material averaged 25,000 negatives and 60,000 prints. Thirty-six million prints were made during the war. By

/ref> According to

The onset of the

The onset of the

"Global Hawk to replace U-2 spy plane in 2015."

''Air Force Times,'' 10 August 2011. Retrieved: 22 August 2011. however, in January 2012, it was instead decided to extend the U-2's service life. Critics have pointed out that the RQ-4's cameras and sensors are less capable and lack all-weather operating capability; however, some of the U-2's sensors could be installed on the RQ-4. In late 2014, Lockheed Martin proposed converting the manned U-2 fleet into UAVs, which would substantially bolster its payload capability;Butler, Amy

"Lockheed updates unmanned U-2 concept."

''Aviation Week'', 24 November 2014. Retrieved: 7 December 2015. however, the USAF declined to provide funding for such an extensive conversion.Drew, James

"U-2 poised to receive radar upgrade, but not un-manned conversion."

''Flightglobal.com'', 31 July 2015. Retrieved: 7 December 2015. During the 2010s, American defense conglomerate

* AeroVironment Wasp III (airplane - electric propulsion)

*

* AeroVironment Wasp III (airplane - electric propulsion)

*

The Central Intelligence Agency and Overhead Reconnaissance: The U-2 and Oxcart Programs, 1954–1974

'. Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, 1992. . * Polmar, Norman. ''Spyplane: The U-2 History Declassified''. London: Zenith Imprint, 2001. . * Stanley, Colonel Roy M. II, USAF (Ret). ''V-Weapons Hunt: Defeating German Secret Weapons.'' Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK: Pen & Sword, 2010. .

National Collection of Aerial Photography

The official archive of British Government declassified aerial photography. {{DEFAULTSORT:Aerial Reconnaissance

Aerial reconnaissance is

Aerial reconnaissance is reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops (skirmisher ...

for a military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

or strategic

Strategy (from Greek στρατηγία ''stratēgia'', "art of troop leader; office of general, command, generalship") is a general plan to achieve one or more long-term or overall goals under conditions of uncertainty. In the sense of the "art ...

purpose that is conducted using reconnaissance aircraft

A reconnaissance aircraft (colloquially, a spy plane) is a military aircraft designed or adapted to perform aerial reconnaissance with roles including collection of imagery intelligence (including using photography), signals intelligence, as ...

. The role of reconnaissance can fulfil a variety of requirements including artillery spotting

An artillery observer, artillery spotter or forward observer (FO) is responsible for directing artillery and mortar fire onto a target. It may be a ''forward air controller'' (FAC) for close air support (CAS) and spotter for naval gunfire sup ...

, the collection of imagery intelligence

Imagery intelligence (IMINT), pronounced as either as ''Im-Int'' or ''I-Mint'', is an intelligence gathering discipline wherein imagery is analyzed (or "exploited") to identify information of intelligence value. Imagery used for defense intelli ...

, and the observation of enemy maneuvers.

History

Early developments

After theFrench Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

, the new rulers became interested in using the balloon

A balloon is a flexible bag that can be inflated with a gas, such as helium, hydrogen, nitrous oxide, oxygen, and air. For special tasks, balloons can be filled with smoke, liquid water, granular media (e.g. sand, flour or rice), or light so ...

to observe enemy manoeuvres and appointed scientist Charles Coutelle to conduct studies using the balloon ''L'Entreprenant'', the first military reconnaissance aircraft. The balloon found its first use in the 1794 conflict with Austria, where in the Battle of Fleurus they gathered information. Moreover, the presence of the balloon had a demoralizing effect on the Austrian troops, which improved the likelihood of victory for the French troops. To operate such balloons, a new unit of the French military, the French Aerostatic Corps

The French Aerostatic Corps or Company of Aeronauts (french: compagnie d'aérostiers) was the world's first balloon unit,Jeremy Beadle and Ian Harrison, ''First, Lasts & Onlys: Military'', p. 42 founded in 1794 to use balloons, primarily for reco ...

, was established; this organisation has been recognised as being the world's first air force

An air force – in the broadest sense – is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an a ...

.

After the invention of photography, primitive aerial photographs were made of the ground from manned and unmanned balloons, starting in the 1860s, and from tethered kites from the 1880s onwards. An example was

After the invention of photography, primitive aerial photographs were made of the ground from manned and unmanned balloons, starting in the 1860s, and from tethered kites from the 1880s onwards. An example was Arthur Batut

Arthur Batut (9 February 1846 – 19 January 1918) was a French photographer and pioneer of aerial photography..

Life

Batut was born in 1846 in Castres, and developed interest in history, archeology and photography. His book on kite aerial photog ...

's kite-borne camera photographs of Labruguière

Labruguière (; Languedocien dialect, Languedocien: ''La Bruguièira'') is a Communes of France, commune in the Tarn (department), Tarn Departments of France, department in southern France.

The Thoré is a river that is part of the commune's east ...

starting from 1889.

In the early 20th century, Julius Neubronner

Julius Gustav Neubronner (8 February 1852 – 17 April 1932) was a German apothecary, inventor, company founder, and a pioneer of amateur photography and film. He was part of a dynasty of apothecaries in Kronberg im Taunus. Neubronner was court ap ...

experimented with pigeon photography

Pigeon photography is an aerial photography technique invented in 1907 by the German apothecary Julius Neubronner, who also used pigeons to deliver medications. A homing pigeon was fitted with an aluminium breast harness to which a lightweight t ...

. These pigeons carried small cameras that incorporated timers. (photographs by Alfred Nobel's rocket and the Bavarian pigeon fleet)

Ludwig Rahrmann in 1891 patented a means of attaching a camera to a large calibre artillery projectile or rocket, and this inspired Alfred Maul

Alfred Maul (1870–1942) was a German engineer who could be thought of as the father of aerial reconnaissance. Maul, who owned a machine works, experimented from 1900 with small solid-propellant sounding rockets.

Background

Although people had lo ...

to develop his Maul Camera Rocket

The Maul Camera Rocket was a rocket for aerial photography developed by Alfred Maul's company from 1903 to 1912. The Maul Camera Rocket was demonstrated in 1912 to the Austrian Army and tested as a means for reconnaissance in the Turkish-Bulgari ...

s starting in 1903. Alfred Nobel

Alfred Bernhard Nobel ( , ; 21 October 1833 – 10 December 1896) was a Swedes, Swedish chemist, engineer, inventor, businessman, and Philanthropy, philanthropist. He is best known for having bequeathed his fortune to establish the Nobel ...

in 1896 had already built the first rocket carrying a camera, which took photographs of the Swedish landscape during its flights. Maul improved his camera rockets and the Austrian Army even tested them in the Turkish-Bulgarian War in 1912 and 1913, but by then and from that time on camera-carrying aircraft were found to be superior. (summary and photo)

The first use of airplanes in combat missions was by the Italian Air Force

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march = (Ordinance March of the Air Force) by Alberto Di Miniello

, mascot =

, anniversaries = 28 March ...

during the Italo-Turkish War

The Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War ( tr, Trablusgarp Savaşı, "Tripolitanian War", it, Guerra di Libia, "War of Libya") was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911, to 18 October 1912. As a result o ...

of 1911–1912. On 23 October 1911, an Italian pilot, Capt. Carlo Piazza, flew over the Turkish lines in Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

to conduct an aerial reconnaissance mission; Another aviation first occurred on November 1 with the first ever dropping of an aerial bomb

An aerial bomb is a type of explosive or incendiary weapon intended to travel through the air on a predictable trajectory. Engineers usually develop such bombs to be dropped from an aircraft.

The use of aerial bombs is termed aerial bombing.

...

, performed by '' Sottotenente'' Giulio Gavotti

Giulio Gavotti (17 October 1882 in Genoa–6 October 1939) was an Italian lieutenant and pilot who fought in the Italo-Turkish War.

Aerial bombardment

On 1 November 1911, he flew his early model Etrich Taube monoplane against Ottoman military in ...

, on Turkish troops from an early model of Etrich Taube

The Etrich ''Taube'', also known by the names of the various later manufacturers who built versions of the type, such as the Rumpler ''Taube'', was a pre-World War I monoplane aircraft. It was the first military aeroplane to be mass-produced in ...

aircraft.

The first reconnaissance flight in Europe took place in Greece, over Thessaly, on 18 October 1912 (5 October by the Julian calendar) over the Ottoman army. The pilot also dropped some hand-grenades over the Turkish Army barracks, although without success. This was the first day of the Balkan wars, and during the same day a similar mission was flown by German mercenaries in Ottoman service in the Thrace front against the Bulgarians. The Greek and the Ottoman mission flown during the same day are the first military aviation combat missions in a conventional war. A few days later, on 16 October 1912, a Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

n Albatros aircraft performed one of Europe's first reconnaissance flight in combat conditions, against the Turkish lines on the Balkan peninsula

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

, during the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars refers to a series of two conflicts that took place in the Balkan States in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan States of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and defe ...

of 1912–1913.

Maturation during the First World War

The use of aerial photography rapidly matured during the

The use of aerial photography rapidly matured during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, as aircraft used for reconnaissance purposes were outfitted with cameras to record enemy movements and defences. At the start of the conflict, the usefulness of aerial photography was not fully appreciated, with reconnaissance being accomplished with map sketching from the air.

Frederick Charles Victor Laws started experiments in aerial photography in 1912 with No. 1 Squadron RAF

Number 1 Squadron, also known as No. 1 (Fighter) Squadron, is a squadron (aviation), squadron of the Royal Air Force. It was the first squadron to fly a VTOL aircraft. It currently operates Eurofighter Typhoon aircraft from RAF Lossiemouth.

Th ...

using the British dirigible ''Beta''. He discovered that vertical photos taken with 60% overlap could be used to create a stereoscopic

Stereoscopy (also called stereoscopics, or stereo imaging) is a technique for creating or enhancing the depth perception, illusion of depth in an image by means of stereopsis for binocular vision. The word ''stereoscopy'' derives . Any stere ...

effect when viewed in a stereoscope, thus creating a perception of depth that could aid in cartography and in intelligence derived from aerial images. The dirigibles were eventually allocated to the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

, so Laws formed the first aerial reconnaissance unit of fixed-wing aircraft; this became No. 3 Squadron RAF

Number 3 Squadron, also known as No. 3 (Fighter) Squadron, of the Royal Air Force operates the Eurofighter Typhoon FGR4 from RAF Coningsby, Lincolnshire, since reforming on 1 April 2006. It was first formed on 13 May 1912 as one of the first squ ...

.

Germany was one of the first countries to adopt the use of a camera for aerial reconnaissance, opting for a Görz

Gorizia (; sl, Gorica , colloquially 'old Gorizia' to distinguish it from Nova Gorica; fur, label=Standard Friulian, Gurize, fur, label= Southeastern Friulian, Guriza; vec, label= Bisiacco, Gorisia; german: Görz ; obsolete English ''Goritz ...

, in 1913. French Military Aviation began the war with several squadrons of Bleriot observation planes, equipped with cameras for reconnaissance. The French Army developed procedures for getting prints into the hands of field commanders in record time.

The

The Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

recon pilots began to use cameras for recording their observations in 1914 and by the Battle of Neuve Chapelle

The Battle of Neuve Chapelle (10–13 March 1915) took place in the First World War in the Artois region of France. The attack was intended to cause a rupture in the German lines, which would then be exploited with a rush to the Aubers Ridge and ...

in 1915 the entire system of German trenches was being photographed. The first purpose-built and practical aerial camera was invented by Captain John Moore-Brabazon

Lieutenant-Colonel John Theodore Cuthbert Moore-Brabazon, 1st Baron Brabazon of Tara, , HonFRPS (8 February 1884 – 17 May 1964), was an English aviation pioneer and Conservative politician. He was the first Englishman to pilot a heavier-than- ...

in 1915 with the help of the Thornton-Pickard

Thornton-Pickard was a British camera manufacturer established in 1888 and closed in 1939. The company was based in Altrincham, near Manchester, and was an early pioneer in the development of the camera industry.

The Thornton-Pickard company w ...

company, greatly enhancing the efficiency of aerial photography. The camera was inserted into the floor of the aircraft and could be triggered by the pilot at intervals.

Moore-Brabazon also pioneered the incorporation of stereoscopic techniques into aerial photography, allowing the height of objects on the landscape to be discerned by comparing photographs taken at different angles. In 1916, the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

made vertical camera axis aerial photos above Italy for map-making.

By the end of the war, aerial cameras had dramatically increased in size and focal power

In optics, optical power (also referred to as dioptric power, refractive power, focusing power, or convergence power) is the degree to which a lens, mirror, or other optical system converges or diverges light. It is equal to the reciprocal of the ...

and were used increasingly frequently as they proved their pivotal military worth; by 1918 both sides were photographing the entire front twice a day and had taken over half a million photos since the beginning of the conflict.

In January 1918, General Allenby

Field Marshal Edmund Henry Hynman Allenby, 1st Viscount Allenby, (23 April 1861 – 14 May 1936) was a senior British Army Officer (armed forces), officer and Imperial Governor. He fought in the Second Boer War and also in the First World ...

used five Australian pilots from No. 1 Squadron AFC to photograph a area in Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

as an aid to correcting and improving maps of the Turkish front. This was a pioneering use of aerial photography as an aid for cartography

Cartography (; from grc, χάρτης , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an im ...

. Lieutenants Leonard Taplin

Lieutenant Leonard Thomas Eaton Taplin (16 December 1895 – 8 July 1961) was an Australian World War I flying ace. During his service in Palestine (region), Palestine, he helped pioneer the use of aerial photography for cartography. He then ...

, Allan Runciman Brown, H. L. Fraser, Edward Patrick Kenny

Lieutenant Edward Patrick Kenny (born January 1888, date of death unknown) was an Australian World War I flying ace

A flying ace, fighter ace or air ace is a military aviator credited with shooting down five or more enemy aircraft during aer ...

, and L. W. Rogers photographed a block of land stretching from the Turkish front lines deep into their rear areas. Beginning 5 January, they flew with a fighter escort to ward off enemy fighters. Using Royal Aircraft Factory BE.12

The Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.12 was a British single-seat aeroplane of The First World War designed at the Royal Aircraft Factory. It was essentially a single-seat version of the B.E.2.

Intended for use as a long-range reconnaissance and bom ...

and Martinsyde

Martinsyde was a British aircraft and motorcycle manufacturer between 1908 and 1922, when it was forced into liquidation by a factory fire.

History

The company was first formed in 1908 as a partnership between H.P. Martin and George Handasyde ...

airplanes, they not only overcame enemy air attacks, but also bucked 65 mile-per-hour winds, anti-aircraft fire, and malfunctioning equipment to complete their task circa 19 January 1918.

Second World War

High-speed reconnaissance aircraft

During 1928, the

During 1928, the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

(RAF) developed an electric heating system for the aerial camera; this innovation allowed reconnaissance aircraft to take pictures from very high altitudes without the camera parts freezing. In 1939, Sidney Cotton

Frederick Sidney Cotton OBE (17 June 1894 – 13 February 1969) was an Australian inventor, photographer and aviation and photography pioneer, responsible for developing and promoting an early colour film process, and largely responsible for t ...

and Flying Officer Maurice Longbottom

Maurice Longbottom (born 30 January 1995) is an Australian rugby league and rugby union player who played his first game for the Australia national rugby sevens team at the 2018 Sydney Sevens tournament of the World Rugby Sevens Series.

Longbot ...

of the RAF suggested that airborne reconnaissance may be a task better suited to fast, small aircraft which would use their speed and high service ceiling to avoid detection and interception. Although this may perhaps seem obvious today with modern reconnaissance tasks performed by fast, high flying aircraft, at the time it was radical thinking.

Cotton and Longbottom proposed the use of

Cotton and Longbottom proposed the use of Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Griff ...

s with their armament and radio

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmit ...

s removed and replaced with extra fuel and cameras. This concept led to the development of the Spitfire PR variants. With their armaments removed, these planes could attain a maximum speed of 396 mph while flying at an altitude of 30,000 feet, and were used for photo-reconnaissance missions. The Spitfire PR was fitted with five cameras, which were heated to ensure good results (while the cockpit was not). In the reconnaissance role, the Spitfire proved to be extremely successful, resulting in numerous Spitfire variants being built specifically for that purpose. These served initially with what later became No. 1 Photographic Reconnaissance Unit (PRU).

Other

Other fighters

Fighter(s) or The Fighter(s) may refer to:

Combat and warfare

* Combatant, an individual legally entitled to engage in hostilities during an international armed conflict

* Fighter aircraft, a warplane designed to destroy or damage enemy warplan ...

were also adapted for photo-reconnaissance, including the British Mosquito

Mosquitoes (or mosquitos) are members of a group of almost 3,600 species of small flies within the family Culicidae (from the Latin ''culex'' meaning " gnat"). The word "mosquito" (formed by ''mosca'' and diminutive ''-ito'') is Spanish for "li ...

and the American P-38 Lightning

The Lockheed P-38 Lightning is an American single-seat, twin piston-engined fighter aircraft that was used during World War II. Developed for the United States Army Air Corps by the Lockheed Corporation, the P-38 incorporated a distinctive tw ...

and P-51 Mustang

The North American Aviation P-51 Mustang is an American long-range, single-seat fighter and fighter-bomber used during World War II and the Korean War, among other conflicts. The Mustang was designed in April 1940 by a team headed by James ...

. Such aircraft were painted in PRU Blue or Pink camouflage colours to make them difficult to spot in the air, and often were stripped of weapons or had engines modified for better performance at high altitude

Altitude or height (also sometimes known as depth) is a distance measurement, usually in the vertical or "up" direction, between a reference datum and a point or object. The exact definition and reference datum varies according to the context ...

s (over 40,000 feet).

The American F-4, a factory modification of the Lockheed P-38 Lightning

The Lockheed P-38 Lightning is an American single-seat, twin piston-engined fighter aircraft that was used during World War II. Developed for the United States Army Air Corps by the Lockheed Corporation, the P-38 incorporated a distinctive twi ...

, replaced the nose-mounted four machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles) a ...

s and cannon with four high-quality K-17 cameras. Approximately 120 F-4 and F-4As were hurriedly made available by March 1942, reaching the 8th Photographic Squadron in Australia by April (the first P-38s to see action). The F-4 had an early advantage of long range and high speed combined with ability to fly at high altitude

Altitude or height (also sometimes known as depth) is a distance measurement, usually in the vertical or "up" direction, between a reference datum and a point or object. The exact definition and reference datum varies according to the context ...

; a potent combination for reconnaissance. In the last half of 1942 Lockheed would produce 96 F-5As, based on the P-38G with all later P-38 photo-reconnaissance variants designated F-5. In its reconnaissance role, the Lightning was so effective that over 1,200 F-4 and F-5 variants were delivered by Lockheed, and it was the United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

's (USAAF) primary photo-reconnaissance type used throughout the war in all combat theatres. The Mustang F-6 arrived later in the conflict and, by spring 1945, became the dominant reconnaissance type flown by the USAAF in the European theatre

The European theatre of World War II was one of the two main theatres of combat during World War II. It saw heavy fighting across Europe for almost six years, starting with Germany's invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 and ending with the ...

. American photo-reconnaissance operations in Europe were centred at RAF Mount Farm

Royal Air Force Station Mount Farm or more simply RAF Mount Farm is a former Royal Air Force station located north of Dorchester, Oxfordshire, England.

History

USAAF use

Mount Farm was originally a satellite airfield for the RAF Photograp ...

, with the resulting photographs transferred to Medmenham for interpretation. Approximately 15,000 Fairchild K-20

The K-20 is an aerial photography camera used during World War II, famously from the Enola Gay's tail gunner position to photograph the nuclear mushroom cloud over Hiroshima. Designed by Fairchild Camera and Instrument, approximately 15,000 were ...

aerial cameras were manufactured for use in Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

reconnaissance aircraft between 1941 and 1945.

The British de Havilland Mosquito

The de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito is a British twin-engined, shoulder-winged, multirole combat aircraft, introduced during the Second World War. Unusual in that its frame was constructed mostly of wood, it was nicknamed the "Wooden Wonder", or ...

excelled in the photo-reconnaissance role; the converted bomber was fitted with three cameras installed in what had been the bomb bay. It had a cruising speed of 255 mph, maximum speed of 362 mph and a maximum altitude of 35,000 feet. The first converted PRU (Photo-Reconnaissance Unit) Mosquito was delivered to RAF Benson

Royal Air Force Benson or RAF Benson is a Royal Air Force (RAF) station located at Benson, near Wallingford, in South Oxfordshire, England. It is a front-line station and home to the RAF's fleet of Westland Puma HC2 support helicopters, use ...

in July 1941 by Geoffrey de Havilland

Captain Sir Geoffrey de Havilland, (27 July 1882 – 21 May 1965) was an English aviation pioneer and aerospace engineer. The aircraft company he founded produced the Mosquito, which has been considered the most versatile warplane ever built,D ...

himself. The PR Mk XVI and later variants had pressurized

{{Wiktionary

Pressurization or pressurisation is the application of pressure in a given situation or environment.

Industrial

Industrial equipment is often maintained at pressures above or below atmospheric.

Atmospheric

This is the process by ...

cockpit

A cockpit or flight deck is the area, usually near the front of an aircraft or spacecraft, from which a Pilot in command, pilot controls the aircraft.

The cockpit of an aircraft contains flight instruments on an instrument panel, and the ...

s and also pressurized central and inner wing tanks to reduce fuel vaporization at high altitude

Altitude or height (also sometimes known as depth) is a distance measurement, usually in the vertical or "up" direction, between a reference datum and a point or object. The exact definition and reference datum varies according to the context ...

. The Mosquito was faster than most enemy

An enemy or a foe is an individual or a group that is considered as forcefully adverse or threatening. The concept of an enemy has been observed to be "basic for both individuals and communities". The term "enemy" serves the social function of d ...

fighters at 35,000 ft,Bowman 2005, p. 21. and could roam almost anywhere. Colonel Roy M. Stanley II of United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Signal ...

(USAF) stated of the aircraft: "I consider the Mosquito the best photo-reconnaissance aircraft of the war".Stanley 2010, p. 35. The United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

(USAAF) designation for the photo-reconnaissance Mosquito was F-8.

Apart from (for example) the Mosquito, most World War II bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching aerial torpedo, torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped ...

s were not as fast as fighters, although they were effective for aerial reconnaissance due to their long range, inherent stability in flight and capacity to carry large camera payloads. American bombers with top speeds of less than 300 mph used for reconnaissance include the B-24 Liberator

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator is an American heavy bomber, designed by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, California. It was known within the company as the Model 32, and some initial production aircraft were laid down as export models des ...

(photo-reconnaissance variant designated F-7), B-25 Mitchell

The North American B-25 Mitchell is an American medium bomber that was introduced in 1941 and named in honor of Major General William "Billy" Mitchell, a pioneer of U.S. military aviation. Used by many Allied air forces, the B-25 served in ...

(F-10) and B-17 Flying Fortress

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress is a four-engined heavy bomber developed in the 1930s for the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC). Relatively fast and high-flying for a bomber of its era, the B-17 was used primarily in the European Theater ...

(F-9). The revolutionary B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is an American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the B-17 Fl ...

was the world's largest combat-operational bomber when it appeared in 1944, with a top speed of over 350 mph which at that time was outstanding for such a large and heavy aircraft; the B-29 also had a pressurized cabin

Cabin pressurization is a process in which conditioned air is pumped into the cabin of an aircraft or spacecraft in order to create a safe and comfortable environment for passengers and crew flying at high altitudes. For aircraft, this air is ...

for high altitude flight. The photographic reconnaissance version of the B-29 was designated F-13 and carried a camera suite of three K-17B, two K-22 and one K-18 with provisions for others; it also retained the standard B-29 defensive armament of a dozen .50 caliber machine gun

The M2 machine gun or Browning .50 caliber machine gun (informally, "Ma Deuce") is a heavy machine gun that was designed towards the end of World War I by John Browning. Its design is similar to Browning's earlier M1919 Browning machine gun, w ...

s. In November 1944 an F-13 conducted the first flight by an Allied aircraft over Tokyo since the Doolittle Raid

The Doolittle Raid, also known as the Tokyo Raid, was an air raid on 18 April 1942 by the United States on the Japanese capital Tokyo and other places on Honshu during World War II. It was the first American air operation to strike the Japan ...

of April 1942. The Consolidated B-32 Dominator

The Consolidated B-32 Dominator (Consolidated Model 34) was an American heavy strategic bomber built for United States Army Air Forces during World War II, which had the distinction of being the last Allied aircraft to be engaged in combat duri ...

was also used for reconnaissance over Japan in August 1945.

The Japanese Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

Mitsubishi Ki-46

The Mitsubishi Ki-46 was a twin-engine reconnaissance aircraft used by the Imperial Japanese Army in World War II. Its Army ''Shiki'' designation was Type 100 Command Reconnaissance Aircraft (); the Allied brevity code name was "Dinah".

Devel ...

, a twin-engined aircraft designed expressly for the reconnaissance role with defensive armament of 1 light machine gun, entered service in 1941. Codename

A code name, call sign or cryptonym is a Code word (figure of speech), code word or name used, sometimes clandestinely, to refer to another name, word, project, or person. Code names are often used for military purposes, or in espionage. They may ...

d "Dinah" this aircraft was fast, elusive and proved difficult for Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

fighters to destroy. More than 1,500 Ki-46s were built and its performance was upgraded later in the war with the Ki-46-III variant. Another purpose-designed reconnaissance aircraft for the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service

The was the Naval aviation, air arm of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). The organization was responsible for the operation of naval aircraft and the conduct of aerial warfare in the Pacific War.

The Japanese military acquired their first air ...

was the carrier-based

Carrier-based aircraft, sometimes known as carrier-capable aircraft or carrier-borne aircraft, are naval aircraft designed for operations from aircraft carriers. They must be able to launch in a short distance and be sturdy enough to withstand ...

, single-engine Nakajima C6N

The Nakajima C6N ''Saiun'' (彩雲, "Iridescent Cloud") was a carrier-based reconnaissance aircraft used by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service in World War II. Advanced for its time, it was the fastest carrier-based aircraft put into service ...

''Saiun'' ("Iridescent Cloud"). Codename

A code name, call sign or cryptonym is a Code word (figure of speech), code word or name used, sometimes clandestinely, to refer to another name, word, project, or person. Code names are often used for military purposes, or in espionage. They may ...

d "Myrt" by the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

, the Nakajima C6N first flew in 1943 and was also highly elusive to American aircraft due to its excellent performance and speed of almost 400 mph. As fate would have it on 15 August 1945, a C6N1 was the last aircraft to be shot down in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. Japan also developed the high-altitude Tachikawa Ki-74

The Tachikawa Ki-74 ( Allied reporting name "Patsy") was a Japanese experimental long-range reconnaissance bomber of World War II. A twin-engine, mid-wing monoplane, it was developed for the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service but never deployed ...

reconnaissance bomber, which was in a similar class of performance as the Mosquito

Mosquitoes (or mosquitos) are members of a group of almost 3,600 species of small flies within the family Culicidae (from the Latin ''culex'' meaning " gnat"). The word "mosquito" (formed by ''mosca'' and diminutive ''-ito'') is Spanish for "li ...

, but only 16 were built and did not see operational service.

The Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

began deploying jet aircraft

A jet aircraft (or simply jet) is an aircraft (nearly always a fixed-wing aircraft) propelled by jet engines.

Whereas the engines in propeller-powered aircraft generally achieve their maximum efficiency at much lower speeds and altitudes, je ...

in combat in 1944, and the twin- jet Arado Ar 234

The Arado Ar 234 ''Blitz'' (English: lightning) is a jet-powered bomber designed and produced by the German aircraft manufacturer Arado. It was the world's first operational turbojet-powered bomber, seeing service during the latter half of the ...

''Blitz'' ("Lightning") reconnaissance bomber was the world's first operational jet-powered bomber. The Ar 234B-1 was equipped with two Rb 50/30 or Rb 75/30 cameras, and its top speed of 460 mph allowed it to outrun the fastest non-jet Allied fighters of the time. The twin piston

A piston is a component of reciprocating engines, reciprocating pumps, gas compressors, hydraulic cylinders and pneumatic cylinders, among other similar mechanisms. It is the moving component that is contained by a cylinder and is made gas-tig ...

-engined Junkers Ju 388

The Junkers Ju 388 '' Störtebeker'' is a World War II German ''Luftwaffe'' multi-role aircraft based on the Ju 88 airframe by way of the Ju 188. It differed from its predecessors in being intended for high altitude operation, with design feature ...

high-altitude bomber was an ultimate evolution of the Ju 88

The Junkers Ju 88 is a German World War II ''Luftwaffe'' twin-engined multirole combat aircraft. Junkers Aircraft and Motor Works (JFM) designed the plane in the mid-1930s as a so-called ''Schnellbomber'' ("fast bomber") that would be too fast f ...

by way of the Ju 188. The photographic reconnaissance Ju 388L variant had a pressurized

{{Wiktionary

Pressurization or pressurisation is the application of pressure in a given situation or environment.

Industrial

Industrial equipment is often maintained at pressures above or below atmospheric.

Atmospheric

This is the process by ...

cockpit

A cockpit or flight deck is the area, usually near the front of an aircraft or spacecraft, from which a Pilot in command, pilot controls the aircraft.

The cockpit of an aircraft contains flight instruments on an instrument panel, and the ...

from the Ju 388's original multi-role conception as not only a bomber but also a night fighter and bomber destroyer

Bomber destroyers were World War II interceptor aircraft intended to destroy enemy bomber aircraft. Bomber destroyers were typically larger and heavier than general interceptors, designed to mount more powerful armament, and often having twin en ...

, due to RLM's perceived threat of the U.S.

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

's high-altitude B-29

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is an American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the B-17 Fly ...

(which ended up not being deployed in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

). Approximately 50 Ju 388Ls were produced under rapidly deteriorating conditions at the end of the war. As with other high performance weapons introduced by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, too many circumstances in the war's logistics had changed by late 1944 for such aircraft to have any impact.

The DFS 228

The DFS 228 was a rocket-powered, high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft designed by the ''Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Segelflug'' (DFS - "German Research Institute for Sailplane Flight") during World War II. By the end of the war, the aircraf ...

was a rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely fr ...

-powered high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft under development in the latter part of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. It was designed by Felix Kracht

Felix Kracht (born 13 May 1912 in Krefeld; died 3 October 2002 in Weyhe) was a German engineer.

After graduating from the Technical University of Aachen, he put his theoretical knowledge into practice at the aeronautical association Flugwissensc ...

at the Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Segelflug

The ''Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Segelflug'' (), or DFS , was formed in 1933 to centralise all gliding activity in Germany, under the directorship of Professor Walter Georgii. It was formed by the nationalisation of the Rhön-Rossitten Ge ...

(German Institute for Sailplane Flight) and in concept is an interesting precursor to the post-war American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

U-2, being essentially a powered long-wingspan

The wingspan (or just span) of a bird or an airplane is the distance from one wingtip to the other wingtip. For example, the Boeing 777–200 has a wingspan of , and a wandering albatross (''Diomedea exulans'') caught in 1965 had a wingspan of ...

glider

Glider may refer to:

Aircraft and transport Aircraft

* Glider (aircraft), heavier-than-air aircraft primarily intended for unpowered flight

** Glider (sailplane), a rigid-winged glider aircraft with an undercarriage, used in the sport of glidin ...

intended solely for the high-altitude aerial reconnaissance role. Advanced features of the DFS 228 design included a pressurized

{{Wiktionary

Pressurization or pressurisation is the application of pressure in a given situation or environment.

Industrial

Industrial equipment is often maintained at pressures above or below atmospheric.

Atmospheric

This is the process by ...

escape capsule for the pilot. The aircraft never flew under rocket power with only unpowered glider prototype

A prototype is an early sample, model, or release of a product built to test a concept or process. It is a term used in a variety of contexts, including semantics, design, electronics, and Software prototyping, software programming. A prototyp ...

s flown prior to May 1945.

Imagery analysis

The collection and interpretation of aerial reconnaissance intelligence became a considerable enterprise during the war. Beginning in 1941,

The collection and interpretation of aerial reconnaissance intelligence became a considerable enterprise during the war. Beginning in 1941, RAF Medmenham

RAF Medmenham is a former Royal Air Force station based at Danesfield House near Medmenham, in Buckinghamshire, England. Activities there specialised in photographic intelligence, and it was once the home of the RAF Intelligence Branch. During ...

was the main interpretation centre for photographic reconnaissance operations in the European

European, or Europeans, or Europeneans, may refer to:

In general

* ''European'', an adjective referring to something of, from, or related to Europe

** Ethnic groups in Europe

** Demographics of Europe

** European cuisine, the cuisines of Europe ...

and Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

theatres.Unlocking Buckinghamshire's Past/ref> The

Central Interpretation Unit

MI4 was a department of the British Directorate of Military Intelligence, Section 4, part of the War Office. It was responsible for aerial reconnaissance and interpretation. It developed into the JARIC intelligence agency. The present day su ...

(CIU) was later amalgamated with the Bomber Command Damage Assessment Section and the Night Photographic Interpretation Section of No 3 Photographic Reconnaissance Unit, RAF Oakington

Royal Air Force Oakington or more simply RAF Oakington was a Royal Air Force station located north of Oakington, Cambridgeshire, England and north-west of Cambridge.

History Second World War

Construction was started in 1939, but was affect ...

, in 1942.Allied Central Interpretation Unit (ACIU)During 1942 and 1943, the CIU gradually expanded and was involved in the planning stages of practically every operation of the war, and in every aspect of intelligence. In 1945, daily intake of material averaged 25,000 negatives and 60,000 prints. Thirty-six million prints were made during the war. By

VE-day

Victory in Europe Day is the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, 8 May 1945, marking the official end of World War II in Europe in the Easter ...

, the print library, which documented and stored worldwide cover, held 5,000,000 prints from which 40,000 reports had been produced.

American personnel had for some time formed an increasing part of the CIU and on 1 May 1944 this was finally recognised by changing the title of the unit to the Allied Central Interpretation Unit (ACIU). There were then over 1,700 personnel on the unit's strength. A large number of photographic interpreters were recruited from the Hollywood Film Studios including Xavier Atencio

Francis Xavier Atencio, also known as X Atencio (September 4, 1919 – September 10, 2017) was an animator and Walt Disney Imagineering, Imagineer for The Walt Disney Company. He is perhaps best known for writing the scripts and song lyrics of th ...

. Two renowned archaeologists also worked there as interpreters: Dorothy Garrod

Dorothy Annie Elizabeth Garrod, CBE, FBA (5 May 1892 – 18 December 1968) was an English archaeologist who specialised in the Palaeolithic period. She held the position of Disney Professor of Archaeology at the University of Cambridge from 193 ...

, the first woman to hold an Oxbridge Chair, and Glyn Daniel

Glyn Edmund Daniel Fellow of the British Academy, FBA, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, FRAI (23 April 1914 – 13 December 1986) was a Wales, Welsh scientist and archaeologist who taught at Cambridge University, ...

, who went on to gain popular acclaim as the host of the television game show ''Animal, Vegetable or Mineral?

''Animal, Vegetable, Mineral?'' was a popular television game show which ran from 1952 to 1959. In the show, a panel of archeologists, art historians, and natural history experts were asked to identify interesting objects or artifacts from muse ...

''.

Sidney Cotton

Frederick Sidney Cotton OBE (17 June 1894 – 13 February 1969) was an Australian inventor, photographer and aviation and photography pioneer, responsible for developing and promoting an early colour film process, and largely responsible for t ...

's aerial photographs were far ahead of their time. Together with other members of his reconnaissance squadron, he pioneered the technique of high-altitude, high-speed photography that was instrumental in revealing the locations of many crucial military and intelligence targets. Cotton also worked on ideas such as a prototype specialist reconnaissance aircraft and further refinements of photographic equipment. At its peak, British reconnaissance flights yielded 50,000 images per day to interpret.

Of particular significance in the success of the work of Medmenham was the use of stereoscopic

Stereoscopy (also called stereoscopics, or stereo imaging) is a technique for creating or enhancing the depth perception, illusion of depth in an image by means of stereopsis for binocular vision. The word ''stereoscopy'' derives . Any stere ...

images, using a between plate overlap of exactly 60%. Despite initial scepticism about the possibility of German rocket development, stereoscopic analysis proved its existence and major operations, including the 1943 offensives against the V-2 rocket

The V-2 (german: Vergeltungswaffe 2, lit=Retaliation Weapon 2), with the technical name ''Aggregat 4'' (A-4), was the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile. The missile, powered by a liquid-propellant rocket engine, was developed ...

development plant at Peenemünde

Peenemünde (, en, "Peene iverMouth") is a municipality on the Baltic Sea island of Usedom in the Vorpommern-Greifswald district in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. It is part of the ''Amt'' (collective municipality) of Usedom-Nord. The communi ...

, were made possible by work carried out at Medmenham. Later offensives were also made against potential launch sites at Wizernes

Wizernes (; vls, Wezerne) is a commune in the Pas-de-Calais department, northern France. It lies southwest of Saint-Omer on the banks of the river Aa at the D928 and D211 road junction. The commune is twinned with Ensdorf, Germany.

Populatio ...

and 96 other launch sites in northern France.

Particularly important sites were measured, from the images, using Swiss stereoautograph

The stereoautograph is a complex opto-mechanical measurement instrument for the evaluation of analog or digital photograms. It is based on the stereoscopy effect by using two aero photos or two photograms of the topography or of buildings from di ...

machines made by Wild (Heerbrugg) and physical models made to facilitate understanding of what was there or what it was for.

It is claimed that Medmanham's greatest operational success was Operation Crossbow

''Crossbow'' was the code name in World War II for Anglo-American operations against the German V-weapons, long range reprisal weapons (V-weapons) programme.

The main V-weapons were the V-1 flying bomb and V-2 rocket – these were launched aga ...

which, from 23 December 1943, destroyed the V-1 V1, V01 or V-1 can refer to version one (for anything) (e.g., see version control)

V1, V01 or V-1 may also refer to:

In aircraft

* V-1 flying bomb, a World War II German weapon

* V1 speed, the maximum speed at which an aircraft pilot may abort ...

infrastructure in northern France."Operation Crossbow", BBC2, broadcast 15 May 2011/ref> According to

R.V. Jones

Reginald Victor Jones , FRSE, LLD (29 September 1911 – 17 December 1997) was a British physicist and scientific military intelligence expert who played an important role in the defence of Britain in by solving scientific and technical pr ...

, photographs were used to establish the size and the characteristic launching mechanisms for both the V-1 flying bomb

The V-1 flying bomb (german: Vergeltungswaffe 1 "Vengeance Weapon 1") was an early cruise missile. Its official Ministry of Aviation (Nazi Germany), Reich Aviation Ministry () designation was Fi 103. It was also known to the Allies as the buz ...

and the V-2 rocket

The V-2 (german: Vergeltungswaffe 2, lit=Retaliation Weapon 2), with the technical name ''Aggregat 4'' (A-4), was the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile. The missile, powered by a liquid-propellant rocket engine, was developed ...

.

Cold War

Immediately after the Second World War, the long range aerial reconnaissance role was quickly taken up by adapted jetbomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching aerial torpedo, torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped ...

s, such as the English Electric Canberra

The English Electric Canberra is a British first-generation, jet-powered medium bomber. It was developed by English Electric during the mid- to late 1940s in response to a 1944 Air Ministry requirement for a successor to the wartime de Havil ...

and its American development the Martin B-57

The Martin B-57 Canberra is an American-built, twin-engined tactical bomber and reconnaissance aircraft that entered service with the United States Air Force (USAF) in 1953. The B-57 is a license-built version of the British English Electric ...

, that were capable of flying higher or faster than enemy aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air. It counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engines ...

or defense

Defense or defence may refer to:

Tactical, martial, and political acts or groups

* Defense (military), forces primarily intended for warfare

* Civil defense, the organizing of civilians to deal with emergencies or enemy attacks

* Defense industr ...

s.Polmar 2001, p. 11.Lewis 1970, p. 371. Shortly after the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

, the United States begun to use RB-47

The Boeing B-47 Stratojet (Boeing company designation Model 450) is a retired American long-Range (aeronautics), range, six-engined, turbojet-powered strategic bomber designed to fly at high subsonic flight, subsonic speed and at high altitude ...

aircraft; these were at first were converted B-47 bombers, but later purposely built as RB-47 reconnaissance aircraft that had no bombing capability. Large cameras were mounted in the plane's belly and a truncated bomb bay

The bomb bay or weapons bay on some military aircraft is a compartment to carry bombs, usually in the aircraft's fuselage, with "bomb bay doors" which open at the bottom. The bomb bay doors are opened and the bombs are dropped when over th ...

was used for carrying photoflash bomb Flashbombs are loaded into a photo-reconnaissance Melsbroek_Air_Base.html"_;"title="De_Havilland_Mosquito_at_Melsbroek_Air_Base">Melsbroek,_Belgium._c.1944

A_photoflash_bomb,_or_flash_bomb,_is_bomb.html" ;"title="Melsbroek Air Base">Melsbroek, B ...

s. Later versions of the RB-47, such as the RB-47H, were extensively modified for signals intelligence

Signals intelligence (SIGINT) is intelligence-gathering by interception of ''signals'', whether communications between people (communications intelligence—abbreviated to COMINT) or from electronic signals not directly used in communication ( ...

(ELINT), with additional equipment operator crew stations in the bomb bay; unarmed weather reconnaissance

Weather reconnaissance is the acquisition of weather data used for research and planning. Typically the term reconnaissance refers to observing weather from the air, as opposed to the ground.

Methods

Aircraft

Helicopters are not built to w ...

WB-47s with cameras and meteorological instruments also served the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Signal ...

(USAF) during the 1960s.Natola 2002, pp. 179–181.

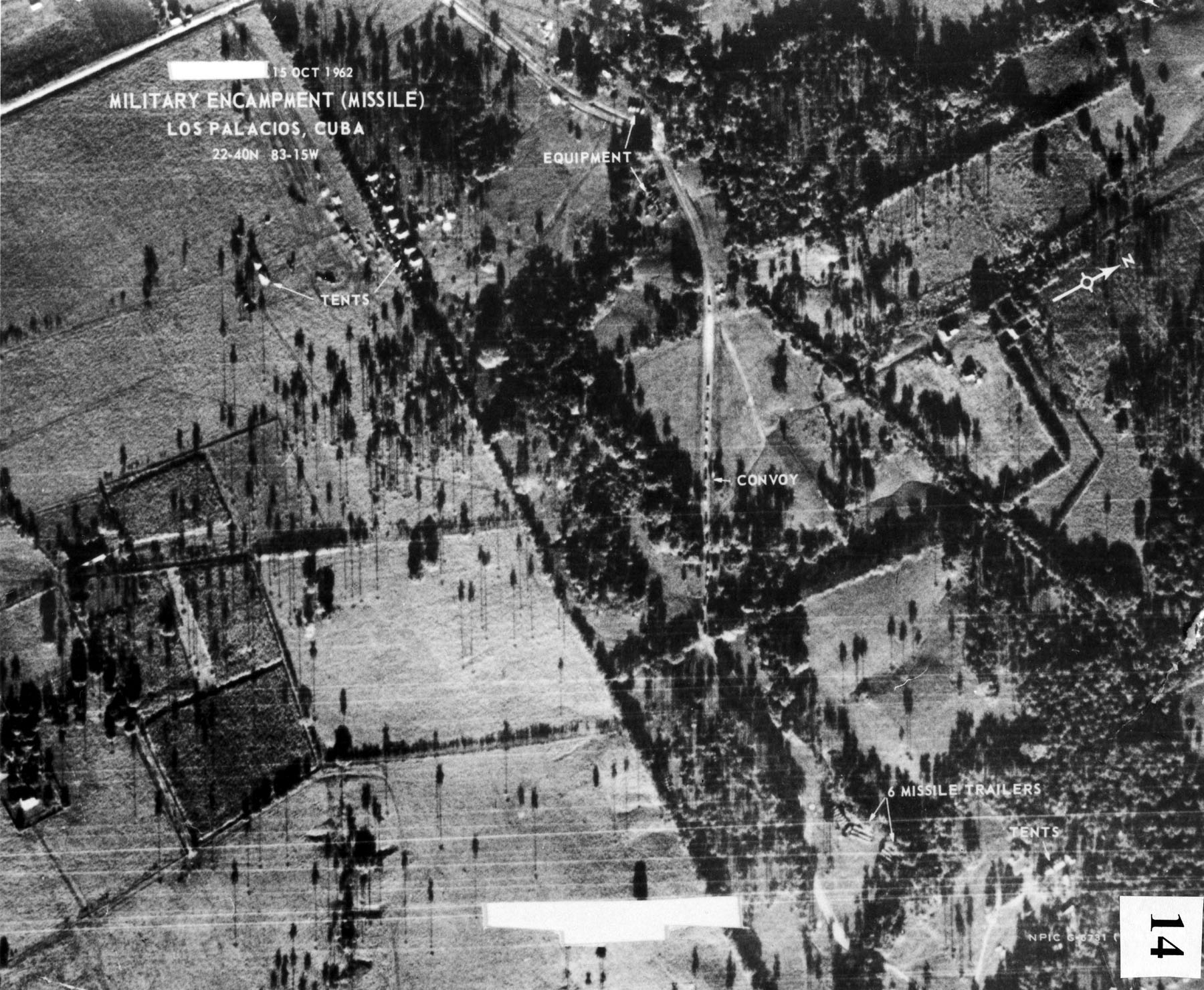

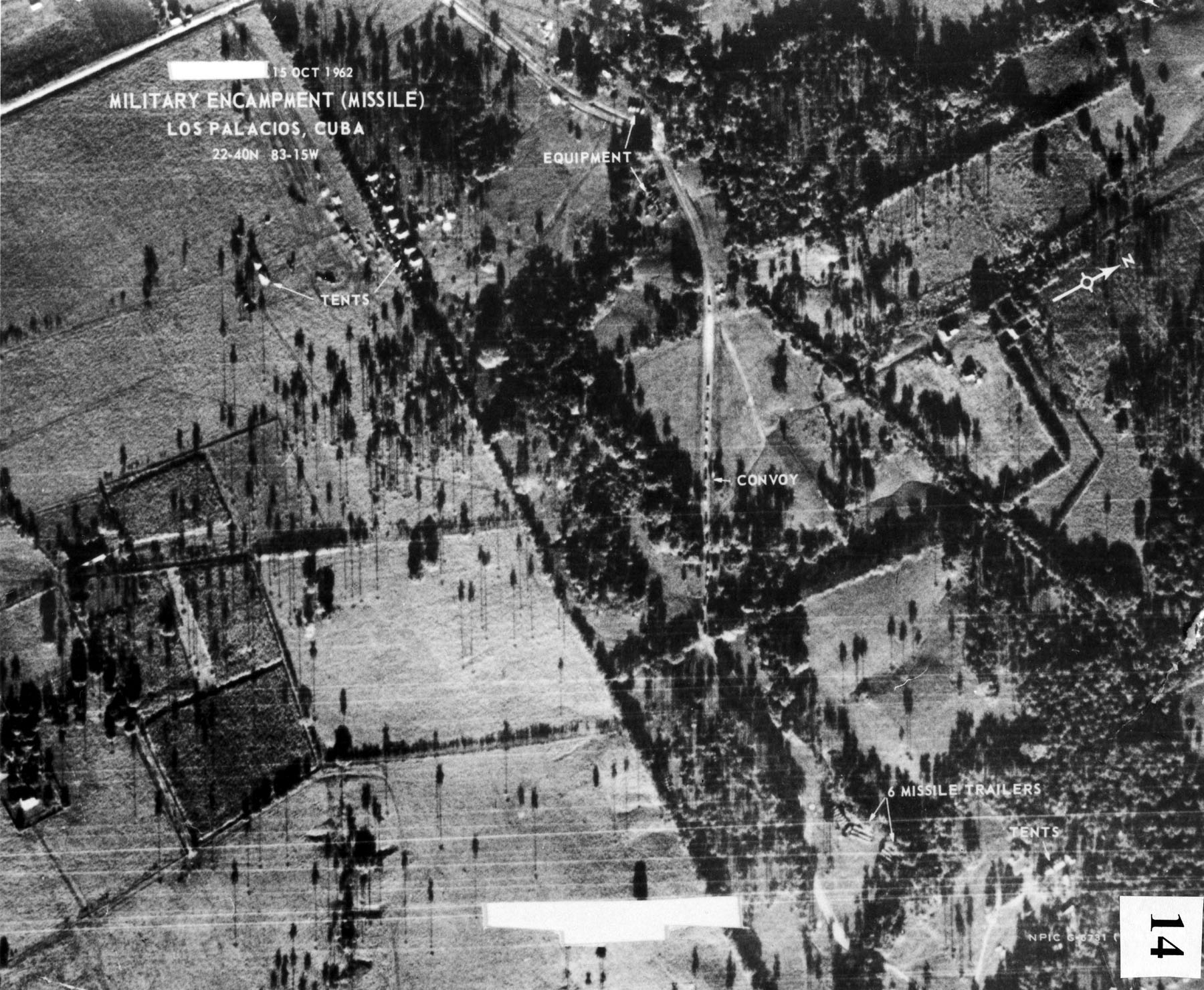

The onset of the

The onset of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

led to development of several highly specialized and clandestine strategic reconnaissance aircraft

A reconnaissance aircraft (colloquially, a spy plane) is a military aircraft designed or adapted to perform aerial reconnaissance with roles including collection of imagery intelligence (including using photography), signals intelligence, as ...

, or spy planes, such as the Lockheed U-2

The Lockheed U-2, nicknamed "''Dragon Lady''", is an American single-jet engine, high altitude reconnaissance aircraft operated by the United States Air Force (USAF) and previously flown by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). It provides day ...

and its successor the SR-71 Blackbird

The Lockheed SR-71 "Blackbird" is a long-range, high-altitude, Mach 3+ strategic reconnaissance aircraft developed and manufactured by the American aerospace company Lockheed Corporation. It was operated by the United States Air Force ...

(both from the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

). Flying these aircraft became an exceptionally demanding task, with crew

A crew is a body or a class of people who work at a common activity, generally in a structured or hierarchical organization. A location in which a crew works is called a crewyard or a workyard. The word has nautical resonances: the tasks involve ...

s specially selected and trained due to the aircraft's extreme performance characteristics in addition to risk of being captured as spies

Spies most commonly refers to people who engage in spying, espionage or clandestine operations.

Spies or The Spies may also refer to:

* Spies (surname), a German surname

* Spies (band), a jazz fusion band

* "Spies" (song), a song by Coldplay

* ...

. The American U-2 shot down in Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

airspace

Airspace is the portion of the atmosphere controlled by a country above its territory, including its territorial waters or, more generally, any specific three-dimensional portion of the atmosphere. It is not the same as aerospace, which is the ...

and capture of its pilot caused political turmoil at the height of the Cold War.

Beginning in the early 1960s, United States aerial and satellite reconnaissance

A reconnaissance satellite or intelligence satellite (commonly, although unofficially, referred to as a spy satellite) is an Earth observation satellite or communications satellite deployed for military or intelligence applications.

Th ...

was coordinated by the National Reconnaissance Office

The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) is a member of the United States Intelligence Community and an agency of the United States Department of Defense which designs, builds, launches, and operates the reconnaissance satellites of the U.S. f ...

(NRO). Risks such as loss or capture of reconnaissance aircraft crewmembers also contributed to U.S.

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

development of the Ryan Model 147

The Ryan Model 147 Lightning Bug is a jet-powered drone, or unmanned aerial vehicle, produced and developed by Ryan Aeronautical from the earlier Ryan Firebee target drone series.

Beginning in 1962, the Model 147 was introduced as a reconnai ...

RPV (Remotely Piloted Vehicle) unmanned drone aircraft which were partly funded by the NRO

NRO may stand for:

* National Reconciliation Ordinance, a Pakistani law

* National Reconnaissance Office, maintains United States reconnaissance

* National Repertory Orchestra, in Colorado

* ''National Review Online'', web version of the magazine ...

during the 1960s.

During the 1960s, the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

opted to convert many of its supersonic

Supersonic speed is the speed of an object that exceeds the speed of sound ( Mach 1). For objects traveling in dry air of a temperature of 20 °C (68 °F) at sea level, this speed is approximately . Speeds greater than five times ...

carrier-based

Carrier-based aircraft, sometimes known as carrier-capable aircraft or carrier-borne aircraft, are naval aircraft designed for operations from aircraft carriers. They must be able to launch in a short distance and be sturdy enough to withstand ...

nuclear

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

* Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

*Nuclear space

*Nuclear ...

bomber, the North American A-5 Vigilante

The North American A-5 Vigilante was an American carrier-based supersonic bomber designed and built by North American Aviation (NAA) for the United States Navy. Prior to 1962 unification of Navy and Air Force designations, it was designated t ...

, into the capable RA-5C Vigilante reconnaissance aircraft. Beginning in the early 1980s, the U.S. Navy outfitted and deployed Grumman F-14 Tomcat

The Grumman F-14 Tomcat is an American carrier-capable supersonic, twin-engine, two-seat, twin-tail, variable-sweep wing fighter aircraft. The Tomcat was developed for the United States Navy's Naval Fighter Experimental (VFX) program after the ...

aircraft in one squadron aboard an aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

with a system called Tactical Airborne Reconnaissance Pod System

The Tactical Airborne Reconnaissance Pod System (TARPS) was a large and sophisticated camera pod carried by the Grumman F-14 Tomcat. It contains three camera bays with different type cameras which are pointed down at passing terrain. It was ori ...

(TARPS), which provided naval aerial reconnaissance capability until the Tomcat's retirement in 2006.Donald, David. "Northrop Grumman F-14 Tomcat, U.S. Navy today". ''Warplanes of the Fleet''. London: AIRtime Publishing Inc, 2004. .

Post Cold War

Since the 1980s, there has been an increasing tendency for militaries to rely upon assets other than manned aircraft to perform aerial reconnaissance. Alternative platforms include the use ofsurveillance satellite

A reconnaissance satellite or intelligence satellite (commonly, although unofficially, referred to as a spy satellite) is an Earth observation satellite or communications satellite deployed for military or intelligence applications.

The ...

s and unmanned aerial vehicle

An unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), commonly known as a drone, is an aircraft without any human pilot, crew, or passengers on board. UAVs are a component of an unmanned aircraft system (UAS), which includes adding a ground-based controller ...

s (UAVs), such as the armed MQ-9 Reaper

The General Atomics MQ-9 Reaper (sometimes called Predator B) is an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) capable of remotely controlled or autonomous flight operations developed by General Atomics Aeronautical Systems (GA-ASI) primarily for the Unit ...

. By 2005, such UAVs could reportedly be equipped with compact cameras capable of identifying an object the size of a milk carton from altitudes of 60,000 feet.

The U-2 has repeatedly been considered for retirement in favour of drones. In 2011, the USAF revealed plans to replace the U-2 with the RQ-4 Global Hawk

The Northrop Grumman RQ-4 Global Hawk is a high-altitude, remotely-piloted surveillance aircraft of the 1990s–2020s. It was initially designed by Ryan Aeronautical (now part of Northrop Grumman), and known as Tier II+ during development. Th ...

, a UAV, within four years;Majumdar, Dave"Global Hawk to replace U-2 spy plane in 2015."

''Air Force Times,'' 10 August 2011. Retrieved: 22 August 2011. however, in January 2012, it was instead decided to extend the U-2's service life. Critics have pointed out that the RQ-4's cameras and sensors are less capable and lack all-weather operating capability; however, some of the U-2's sensors could be installed on the RQ-4. In late 2014, Lockheed Martin proposed converting the manned U-2 fleet into UAVs, which would substantially bolster its payload capability;Butler, Amy

"Lockheed updates unmanned U-2 concept."

''Aviation Week'', 24 November 2014. Retrieved: 7 December 2015. however, the USAF declined to provide funding for such an extensive conversion.Drew, James

"U-2 poised to receive radar upgrade, but not un-manned conversion."

''Flightglobal.com'', 31 July 2015. Retrieved: 7 December 2015. During the 2010s, American defense conglomerate

Lockheed Martin

The Lockheed Martin Corporation is an American aerospace, arms, defense, information security, and technology corporation with worldwide interests. It was formed by the merger of Lockheed Corporation with Martin Marietta in March 1995. It ...

promoted its proposal to develop a hypersonic

In aerodynamics, a hypersonic speed is one that exceeds 5 times the speed of sound, often stated as starting at speeds of Mach 5 and above.

The precise Mach number at which a craft can be said to be flying at hypersonic speed varies, since in ...

UAV

An unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), commonly known as a drone, is an aircraft without any human pilot, crew, or passengers on board. UAVs are a component of an unmanned aircraft system (UAS), which includes adding a ground-based controller ...

, which it referred to the SR-72 in allusion to its function as a spiritual successor to the retired SR-71 Blackbird. The company has also developed several other reconnaissance UAVs, such as the Lockheed Martin RQ-170 Sentinel

The Lockheed Martin RQ-170 Sentinel is an American unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) developed by Lockheed Martin and operated by the United States Air Force (USAF) for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). While the USAF has released few details ...

.

Technologies

Miniature UAVs

Due to the low cost of miniature UAVs, this technology brings aerial reconnaissance into the hands of soldiers on the ground. The soldier on the ground can both control the UAV and see its output, yielding great benefit over a disconnected approach. With small systems being man packable, operators are now able to deploy air assets quickly and directly. The low cost and ease of operation of these miniature UAVs has enabled forces such as the Libyan Rebels to use miniature UAVs. * AeroVironment Wasp III (airplane - electric propulsion)

*

* AeroVironment Wasp III (airplane - electric propulsion)

* Aeryon Scout

Aeryon Scout is a small reconnaissance aircraft, reconnaissance unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) that was designed and built by Aeryon Labs of Waterloo, Ontario, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. The vehicle was developed between 2007 and 2009 and produced ...

/ Aeryon SkyRanger (VTOL Rotorcraft) - Some UAVs are small enough to carry in a backpack with similar functionality to larger ones

* EMT Aladin EMT Aladin (German: ''Abbildende Luftgestützte Aufklärungsdrohne im Nächstbereich'', airborne reconnaissance drone for close area imaging) is a small, man-portable light reconnaissance miniature unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) employed by the Bund ...

(aircraft - electric - Made in Germany)

* Bramor C4EYE

The Bramor C4EYE is a tactical reconnaissance UAV classified as a NATObr>class 1 mini tactical dronewith less than 5 kg MTOW. It was developed and built by C-Astral Aerospace Ltd from Ajdovščina in Slovenia.

It is equipped with an EO/IR/L ...

(aircraft - electric - Made in Slovenia)

* Bayraktar Mini UAV

Bayraktar Mini UAV is a miniature UAV produced by Turkish company Baykar.

Development

With the concept of short range day and night aerial reconnaissance and surveillance applications, system design activities started within 2004. Initial prot ...

(aircraft - electric - Made in Turkey)

* RQ-84Z Areohawk (aircraft - electric - Made in New Zealand)

Low cost miniature UAVs demand increasingly miniature imaging payloads. Developments in miniature electronics have fueled the development of increasingly capable surveillance payloads, allowing miniature UAVs to provide high levels of capability in never before seen packages.

Reconnaissance pods

Reconnaissance pods can be carried by fighter-bomber aircraft. Examples include the BritishDigital Joint Reconnaissance Pod

The Digital Joint Reconnaissance Pod (or DJRP) is a wide area tactical reconnaissance pod produced by Thales Optronics of Bury St Edmunds, England. It is the latest version of a pod produced for the UKMoD and the RAF Jaguar force, originally dev ...

(DJRP); Chinese KZ900

The KZ900 reconnaissance pod is an airborne signals intelligence (SIGINT) pod, used by the Chinese military, that was first revealed to the public at the China International Aviation & Aerospace Exhibition in Zhuhai, in 1998. It was designed by S ...

; UK RAPTOR

Raptor or RAPTOR may refer to:

Animals

The word "raptor" refers to several groups of bird-like dinosaurs which primarily capture and subdue/kill prey with their talons.

* Raptor (bird) or bird of prey, a bird that primarily hunts and feeds on v ...

; and the US Navy's F-14 Tomcat Tactical Airborne Reconnaissance Pod System

The Tactical Airborne Reconnaissance Pod System (TARPS) was a large and sophisticated camera pod carried by the Grumman F-14 Tomcat. It contains three camera bays with different type cameras which are pointed down at passing terrain. It was ori ...

(TARPS). Some aircraft made for non-military applications also have reconnaissance pods, i.e. the Qinetiq Mercator.

See also

*Aerial photography

Aerial photography (or airborne imagery) is the taking of photographs from an aircraft or other airborne platforms. When taking motion pictures, it is also known as aerial videography.

Platforms for aerial photography include fixed-wing aircra ...

* Aerorozvidka

Aerorozvidka ( uk, Аеророзвідка, "aerial reconnaissance") is a team and NGO that promotes creating and implementing netcentric and robotic military capabilities for the security and defense forces of Ukraine. Aerorozvidka exemplifies ...

* Imagery intelligence

Imagery intelligence (IMINT), pronounced as either as ''Im-Int'' or ''I-Mint'', is an intelligence gathering discipline wherein imagery is analyzed (or "exploited") to identify information of intelligence value. Imagery used for defense intelli ...

* National Collection of Aerial Photography

The National Collection of Aerial Photography is a photographic archive in Edinburgh, Scotland, containing 26 million aerial photographs of worldwide historic events and places. From 2008–2015 it was part of the Royal Commission on the Ancient an ...

* Surveillance aircraft

A surveillance aircraft is an aircraft used for surveillance. They are operated by military forces and other government agencies in roles such as intelligence gathering, battlefield surveillance, airspace surveillance, reconnaissance, observa ...

* Spatial reconnaissance

:''This article incorporates text from thUnited States Governmentaccess site.''

Spatial reconnaissance, or "space reconnaissance", is the reconnaissance of any celestial bodies in space by use of spacecraft and satellite photography. NASA person ...

* United States aerial reconnaissance of the Soviet Union

Between 1946 and 1960, the United States Air Force conducted aerial reconnaissance flights over the Soviet Union in order to determine the size, composition, and disposition of Soviet forces. Aircraft used included the Boeing B-47 Stratojet bomb ...

* List of United States Air Force reconnaissance aircraft

This is a list of aircraft used by the United States Air Force and its predecessor organizations for combat aerial reconnaissance and aerial mapping.

The first aircraft acquired by the Aeronautical Division, U.S. Signal Corps were not fighters o ...

References

Citations

Bibliography

* Bowman, Martin. ''de Havilland Mosquito'' (Crowood Aviation series). Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, UK: The Crowood Press, 2005. . * Lewis, Peter. ''British Racing and Record Breaking Aircraft''. London: Putnam, 1970. . * Natola, Mark. "Boeing B-47 Stratojet." ''Schiffer Publishing Ltd'', 2002. . * Pedlow, Gregory W. & Donald E Welzenbach.The Central Intelligence Agency and Overhead Reconnaissance: The U-2 and Oxcart Programs, 1954–1974