Adlai E. Stevenson II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Adlai Ewing Stevenson II (; February 5, 1900 – July 14, 1965) was an American politician and diplomat who was twice the Democratic nominee for

Adlai Ewing Stevenson II was born in

Adlai Ewing Stevenson II was born in

On December 1, 1928, Stevenson married Ellen Borden, a well-to-do socialite. The young couple soon became popular and familiar figures on the Chicago social scene; they especially enjoyed attending and hosting costume parties. They had three sons: Adlai Stevenson III, who would become a U.S. Senator; Borden Stevenson, and John Fell Stevenson. In 1935, Adlai and Ellen purchased a tract of land along the

On December 1, 1928, Stevenson married Ellen Borden, a well-to-do socialite. The young couple soon became popular and familiar figures on the Chicago social scene; they especially enjoyed attending and hosting costume parties. They had three sons: Adlai Stevenson III, who would become a U.S. Senator; Borden Stevenson, and John Fell Stevenson. In 1935, Adlai and Ellen purchased a tract of land along the

In 1948, Stevenson was chosen by Jacob Arvey, leader of the powerful Chicago Democratic political organization, to be the Democratic candidate in the Illinois gubernatorial race against the incumbent Republican,

In 1948, Stevenson was chosen by Jacob Arvey, leader of the powerful Chicago Democratic political organization, to be the Democratic candidate in the Illinois gubernatorial race against the incumbent Republican,

Early in 1952, while Stevenson was still governor of Illinois, President

Early in 1952, while Stevenson was still governor of Illinois, President  At the convention, Stevenson, as governor of the host state, was assigned to give the welcoming address to the delegates. His speech was so stirring and witty that it invigorated efforts to secure the nomination for him, in spite of his continued protests that he was not a presidential candidate. In his welcoming speech he poked fun at the

At the convention, Stevenson, as governor of the host state, was assigned to give the welcoming address to the delegates. His speech was so stirring and witty that it invigorated efforts to secure the nomination for him, in spite of his continued protests that he was not a presidential candidate. In his welcoming speech he poked fun at the

Following his defeat, Stevenson in 1953 made a well-publicized world tour through Asia, the Middle East and Europe, writing about his travels for '' Look'' magazine. His political stature as head of the Democratic Party gave him access to many foreign leaders and dignitaries. He was elected a Fellow of the

Following his defeat, Stevenson in 1953 made a well-publicized world tour through Asia, the Middle East and Europe, writing about his travels for '' Look'' magazine. His political stature as head of the Democratic Party gave him access to many foreign leaders and dignitaries. He was elected a Fellow of the

Unlike 1952, Stevenson was an announced, active candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1956. Initially, with polls showing Eisenhower headed for a landslide re-election, few Democrats wanted the 1956 nomination, and Stevenson hoped that he could win the nomination without a serious contest, and without entering any presidential primaries. However, on September 24, 1955, Eisenhower suffered a serious heart attack. Although he recovered and eventually decided to run for a second term, concerns about his health led two prominent Democrats, Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver and New York Governor Averell Harriman, to decide to challenge Stevenson for the Democratic nomination. After being told by his aides that he needed to enter and win several presidential primaries to defeat Kefauver and Harriman, Stevenson entered and campaigned in the Minnesota, Florida, and California primaries.(White, p. 58) Stevenson was upset in the Minnesota primary by Kefauver, who successfully portrayed him as a "captive" of corrupt Chicago political bosses and "a corporation lawyer out of step with regular Democrats". Stevenson next battled Kefauver in the Florida primary, where he agreed to debate Kefauver on radio and television.(McKeever, p. 374) Stevenson later joked that in Florida he had appealed to the state's citrus farmers by "bitterly denouncing the Japanese beetle and fearlessly attacking the Mediterranean fruit fly". He narrowly defeated Kefauver in Florida by 12,000 votes, and then won the California primary over Kefauver with 63% of the vote, effectively ending Kefauver's presidential bid.

At the

Unlike 1952, Stevenson was an announced, active candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1956. Initially, with polls showing Eisenhower headed for a landslide re-election, few Democrats wanted the 1956 nomination, and Stevenson hoped that he could win the nomination without a serious contest, and without entering any presidential primaries. However, on September 24, 1955, Eisenhower suffered a serious heart attack. Although he recovered and eventually decided to run for a second term, concerns about his health led two prominent Democrats, Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver and New York Governor Averell Harriman, to decide to challenge Stevenson for the Democratic nomination. After being told by his aides that he needed to enter and win several presidential primaries to defeat Kefauver and Harriman, Stevenson entered and campaigned in the Minnesota, Florida, and California primaries.(White, p. 58) Stevenson was upset in the Minnesota primary by Kefauver, who successfully portrayed him as a "captive" of corrupt Chicago political bosses and "a corporation lawyer out of step with regular Democrats". Stevenson next battled Kefauver in the Florida primary, where he agreed to debate Kefauver on radio and television.(McKeever, p. 374) Stevenson later joked that in Florida he had appealed to the state's citrus farmers by "bitterly denouncing the Japanese beetle and fearlessly attacking the Mediterranean fruit fly". He narrowly defeated Kefauver in Florida by 12,000 votes, and then won the California primary over Kefauver with 63% of the vote, effectively ending Kefauver's presidential bid.

At the

At the United Nations Stevenson worked hard to support

At the United Nations Stevenson worked hard to support

Historian

Historian  The

The

Adlai E. Stevenson Papers

at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library,

John J.B. Shea Papers on Adlai E. Stevenson

at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library,

Adlai Stevenson Center on Democracy

* Adapted parts from

part of a series on notable American Unitarians

The Adlai E. Stevenson Historic Home

in Libertyville, Illinois. Open to the public.

Adlai Today

includes speeches, photographs, and more.

Text of Stevenson's First Presidential Nominee Acceptance

* ttp://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/adlaistevensonjfkeulogy.htm Text and Audio of Stevenson's UN Memorial Remarks for JFKbr>Text and Audio Stevenson's UN Memorial Remarks for Eleanor Roosevelt

* ttp://ufdc.ufl.edu/foto/results/?t=adlai Open Access Photos of Adlai Stevensonin the

Adlai Stevenson

interviewed by Mike Wallace on ''The Mike Wallace Interview'' June 1, 1958

''Booknotes'' interview with Porter McKeever on ''Adlai Stevenson: His Life and Legacy'', August 6, 1989"Adlai Stevenson, Presidential Contender"

from C-SPAN's '' The Contenders''

Adlai Stevenson II

–

Helen Davis Stevenson

–

Stevenson faced anti-U.N. mob in 1963 – Pantagraph

(Bloomington, Illinois, newspaper) *Albert Herling worked on Stevenson's 1956 campaign among others. His campaign

President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

. He was the grandson of Adlai Stevenson I

Adlai Ewing Stevenson (October 23, 1835 – June 14, 1914) was an American politician who served as the 23rd vice president of the United States from 1893 to 1897. He had served as a U.S. Representative from Illinois in the late 1870s and ...

, the 23rd vice president of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest officer in the executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks first in the presidential line of succession. The vice ...

.

Raised in Bloomington, Illinois, Stevenson was a member of the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

. He served in numerous positions in the federal government during the 1930s and 1940s, including the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, Federal Alcohol Administration, Department of the Navy Navy Department or Department of the Navy may refer to:

* United States Department of the Navy,

* Navy Department (Ministry of Defence), in the United Kingdom, 1964-1997

* Confederate States Department of the Navy, 1861-1865

* Department of the ...

, and the State Department. In 1945, he served on the committee that created the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

, and he was a member of the initial U.S. delegations to the UN.

In 1948, he was elected governor of Illinois

The governor of Illinois is the head of government of Illinois, and the various agencies and departments over which the officer has jurisdiction, as prescribed in the state constitution. It is a directly elected position, votes being cast by p ...

, defeating incumbent governor Dwight H. Green

Dwight Herbert Green (January 9, 1897 – February 20, 1958) was an American politician who served as the 30th Governor of the US state of Illinois, serving from 1941 to 1949.

From childhood to early adulthood

Green was born in Ligonier, No ...

in an upset. As governor, he reformed the state police, cracked down on illegal gambling, improved the state highways, and attempted to cleanse the state government of corruption. Stevenson also sought, with mixed success, to reform the Illinois state constitution and introduced several crime bills in the state legislature.

In the 1952

Events January–February

* January 26 – Black Saturday in Egypt: Rioters burn Cairo's central business district, targeting British and upper-class Egyptian businesses.

* February 6

** Princess Elizabeth, Duchess of Edinburgh, becomes m ...

and 1956

Events

January

* January 1 – The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium ends in Sudan.

* January 8 – Operation Auca: Five U.S. evangelical Christian missionaries, Nate Saint, Roger Youderian, Ed McCully, Jim Elliot and Pete Fleming, ar ...

presidential elections, he was chosen as the Democratic nominee for president, but was defeated in a landslide by Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

both times. In 1960, he unsuccessfully sought the Democratic presidential nomination for a third time at the Democratic National Convention. After President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

was elected, he appointed Stevenson as the United States Ambassador to the United Nations. Two major events Stevenson dealt with during his time as UN ambassador were the Bay of Pigs Invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called ''Invasión de Playa Girón'' or ''Batalla de Playa Girón'' after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in 1961 by Cuban exiles, covertly fin ...

of Cuba in April 1961 and the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962.

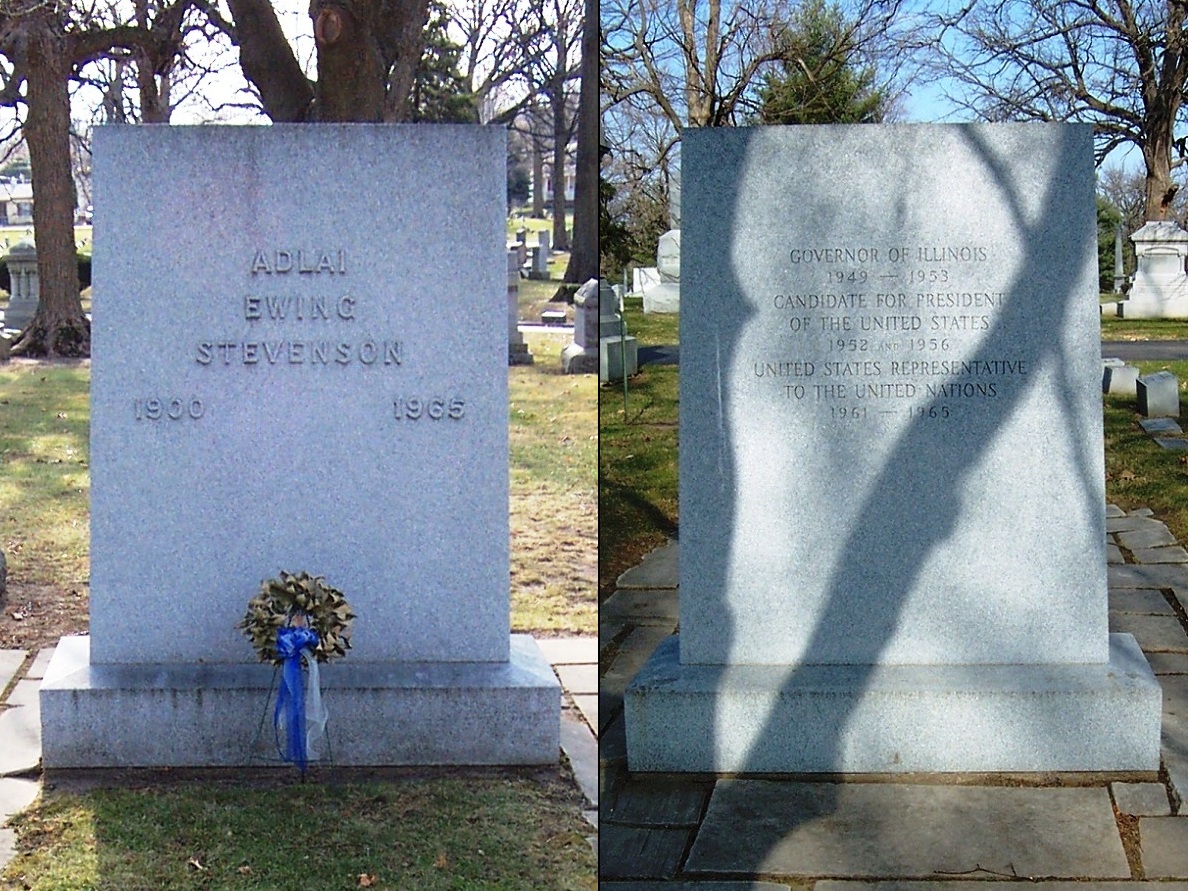

Stevenson served as UN ambassador from January 1961 until his death during a visit to London on July 14, 1965. He is buried in Evergreen Cemetery in his hometown of Bloomington, Illinois.

Early life and education

Adlai Ewing Stevenson II was born in

Adlai Ewing Stevenson II was born in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

, California, in a neighborhood now designated as the North University Park Historic District

The North University Park Historic District is a historic district in the North University Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, California. The district is bounded by West Adams Boulevard on the north, Magnolia Avenue on the west, Hoover Street ...

. His home and birthplace at 2639 Monmouth Avenue has been designated as a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument. He was a member of a prominent Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

political family. His grandfather and namesake Adlai Stevenson I

Adlai Ewing Stevenson (October 23, 1835 – June 14, 1914) was an American politician who served as the 23rd vice president of the United States from 1893 to 1897. He had served as a U.S. Representative from Illinois in the late 1870s and ...

was Vice President of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest officer in the executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks first in the presidential line of succession. The vice ...

under President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

from 1893 to 1897. His father, Lewis Stevenson, never held an elected office, but was appointed Illinois Secretary of State

The Secretary of State of Illinois is one of the six elected executive state offices of the government of Illinois, and one of the 47 secretaries of states in the United States. The Illinois Secretary of State keeps the state records, laws, libr ...

(1914–1917) and was considered a strong contender for the Democratic vice-presidential nomination in 1928. A maternal great-grandfather, Jesse W. Fell

Jesse W. Fell (November 10, 1808 – February 25, 1887) was an American businessman and landowner. He was instrumental in the founding of Illinois State University as well as Normal, Pontiac, Clinton, Towanda, Dwight, DeWitt County and Liv ...

, had been a close friend and campaign manager for Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

in his 1858 US Senate race; Stevenson often referred to Fell as his favorite ancestor. Stevenson's eldest son, Adlai E. Stevenson III, became a U.S. Senator from Illinois (1970–1981). His mother was Helen Davis Stevenson, and he had an older sister, Elizabeth Stevenson Ives, an author who was called "Buffie". Actor McLean Stevenson

Edgar "Mac" McLean Stevenson Jr. (November 14, 1927 – February 15, 1996) was an American actor and comedian. He is best known for his role as Lieutenant Colonel Henry Blake in the television series ''M*A*S*H'', which earned him a Golden Glob ...

was a second cousin once removed

Most generally, in the lineal kinship system used in the English-speaking world, a cousin is a type of familial relationship in which two relatives are two or more familial generations away from their most recent common ancestor. Commonly, ...

. He was the nephew by marriage of novelist Mary Borden

Mary Borden (May 15, 1886 – December 2, 1968) (married names: Mary Turner; Mary Spears, Lady Spears; pseud. Bridget Maclagan) was an American-British novelist and poet whose work drew on her experiences as a war nurse. She was the second of ...

, and she assisted in the writing of some of his political speeches.

Stevenson was raised in the city of Bloomington, Illinois; his family was a member of Bloomington's upper class and lived in one of the city's well-to-do neighborhoods. On December 30, 1912, at the age of twelve, Stevenson accidentally killed Ruth Merwin, a 16-year-old friend, while demonstrating drill technique with a rifle, inadvertently left loaded, during a party at the Stevenson home. Stevenson was devastated by the accident and rarely mentioned or discussed it as an adult, even with his wife and children. However, in 1955 Stevenson heard about a woman whose son had experienced a similar tragedy. He wrote to her that she should tell her son that "he must now live for two", which Stevenson's friends took to be a reference to the shooting incident.

Stevenson left Bloomington High School after his junior year and attended University High School in Normal, Illinois

Normal is a town in McLean County, Illinois, United States. As of the 2020 census, the town's population was 52,736. Normal is the smaller of two principal municipalities of the Bloomington–Normal metropolitan area, and Illinois' seventh most ...

, Bloomington's "twin city", just to the north. He then went to boarding school in Connecticut at The Choate School

Choate Rosemary Hall (often known as Choate; ) is a private, co-educational, college-preparatory boarding school in Wallingford, Connecticut, United States. Choate is currently ranked as the second best boarding school and third best private hi ...

(now Choate Rosemary Hall), where he played on the tennis team, acted in plays, and was elected editor-in-chief of ''The Choate News'', the school newspaper. Upon his graduation from Choate in 1918, he enlisted in the United States Naval Reserve

The United States Navy Reserve (USNR), known as the United States Naval Reserve from 1915 to 2005, is the Reserve Component (RC) of the United States Navy. Members of the Navy Reserve, called Reservists, are categorized as being in either the Se ...

and served at the rank of seaman apprentice

Constructionman Apprenticevariation

Fireman Apprenticevariation

Airman Apprenticevariation

Seaman Apprenticeinsignia

Collarinsignia

Seaman apprentice is the second lowest enlisted rate in the U.S. Navy, U.S. Coast Guard, an ...

, but his training was completed too late for him to participate in World War I.

He attended Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

, becoming managing editor of ''The Daily Princetonian

''The Daily Princetonian'', originally known as ''The Princetonian'' and nicknamed the Prince, is the independent daily student newspaper of Princeton University.

Founded on June 14, 1876 as ''The'' ''Princetonian'', it changed its name to ''T ...

'', a member of the American Whig-Cliosophic Society

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, p ...

, a member of the Quadrangle Club, and received a B.A. degree in 1922 in literature and history. Under prodding from his father he then went to Harvard Law School, but found the law to be "uninteresting", and withdrew after failing several classes. He returned to Bloomington where he wrote for the family newspaper, ''The Daily Pantagraph

''The Pantagraph'' is a daily newspaper that serves Bloomington–Normal, Illinois, along with 60 communities and eight counties in the Central Illinois area. Its headquarters are in Bloomington, Illinois, Bloomington and it is owned by Lee Ente ...

'', which was founded by his maternal great-grandfather Jesse Fell. The ''Pantagraph'', which had one of the largest circulations of any newspaper in Illinois outside the Chicago area, was a main source of the Stevenson family's wealth. Following his mother's death in 1935, Adlai inherited one-quarter of the ''Pantagraph's'' stock, providing him with a large, dependable source of income for the rest of his life.

A year after leaving Harvard, Stevenson became interested in the law again after talking to Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (March 8, 1841 – March 6, 1935) was an American jurist and legal scholar who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1902 to 1932.Holmes was Acting Chief Justice of the Un ...

When he returned home to Bloomington, he decided to finish his degree at Northwestern University School of Law

Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law is the law school of Northwestern University, a private research university. It is located on the university's Chicago campus. Northwestern Law has been ranked among the top 14, or "T14" law s ...

, attending classes during the week and returning to Bloomington on the weekends to write for the ''Pantagraph''. Stevenson received his J.D. degree from Northwestern in 1926 and passed the Illinois state bar examination that year. He obtained a position at Cutting, Moore & Sidley, one of Chicago's oldest and most prestigious law firms.

Family and religion

On December 1, 1928, Stevenson married Ellen Borden, a well-to-do socialite. The young couple soon became popular and familiar figures on the Chicago social scene; they especially enjoyed attending and hosting costume parties. They had three sons: Adlai Stevenson III, who would become a U.S. Senator; Borden Stevenson, and John Fell Stevenson. In 1935, Adlai and Ellen purchased a tract of land along the

On December 1, 1928, Stevenson married Ellen Borden, a well-to-do socialite. The young couple soon became popular and familiar figures on the Chicago social scene; they especially enjoyed attending and hosting costume parties. They had three sons: Adlai Stevenson III, who would become a U.S. Senator; Borden Stevenson, and John Fell Stevenson. In 1935, Adlai and Ellen purchased a tract of land along the Des Plaines River

The Des Plaines River () is a river that flows southward for U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed May 13, 2011 through southern Wisconsin and northern Illinois''American Her ...

near Libertyville, Illinois, a wealthy suburb of Chicago. They built a home on the property and it served as Stevenson's official residence for the rest of his life. Although he spent relatively little time there due to his career, Stevenson did consider the estate to be his home, and in the 1950s, he was often called "The Man from Libertyville" by the national news media. Stevenson also purchased a farm in northwestern Illinois, just outside Galena, where he frequently rode horses and kept some cattle.

On December 12, 1949, Adlai and Ellen were divorced; their son Adlai III later recalled that "There hadn't been a good relationship for a long time. I remember her llenas the unreasonable one, not only with Dad, but with us and the servants. I was embarrassed by her peremptory way with servants." Several of Stevenson's biographers have written that his wife suffered from mental illness: "Incidents that went from petulant to bizarre to nasty generally have been described without placing them in the context of the progression of erincreasingly serious mental illness. It was an illness that those closest to her – including Adlai for long after the divorce – were slow and reluctant to recognize. Hindsight, legal proceedings, and psychiatric testimony now make understandable the behavior that baffled and saddened her family." Stevenson did not remarry after his divorce, but instead dated a number of prominent women throughout the rest of his life, including Alicia Patterson

Alicia Patterson (October 15, 1906 – July 2, 1963) was an American journalist, the founder and editor of ''Newsday''. With Neysa McMein, she created the ''Deathless Deer'' comic strip in 1943.

Early life

Patterson was the middle daughter of Al ...

, Marietta Tree, and Betty Beale.

Stevenson belonged to the Unitarian faith, and was a longtime member of Bloomington's Unitarian church. However, he also occasionally attended Presbyterian services in Libertyville, where a Unitarian church was not present, and as governor he became close friends with the Rev. Richard Graebel, the pastor of Springfield's Presbyterian church.(Baker, p. 358) Graebel "acknowledged that Stevenson's Unitarian rearing had imbued him with the means of translating religious and ethical values into civic issues". According to one historian "religion never disappeared entirely from his public messages – it was indeed part of his appeal".

Early career

In July 1933, Stevenson took a job opportunity as special attorney and assistant toJerome Frank

Jerome New Frank (September 10, 1889 – January 13, 1957) was an American legal philosopher and author who played a leading role in the legal realism movement. He was Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, and a United States circu ...

, the general counsel

A general counsel, also known as chief counsel or chief legal officer (CLO), is the chief in-house lawyer for a company or a governmental department.

In a company, the person holding the position typically reports directly to the CEO, and their ...

of the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA), a part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal. Following the repeal of Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcohol ...

in December 1933, Stevenson changed jobs, becoming chief attorney for the Federal Alcohol Control Administration (FACA), a subsidiary of the AAA which regulated the activities of the alcohol industry.

In 1935, Stevenson returned to Chicago to practice law. He became involved in civic activities, particularly as chairman of the Chicago branch of the Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies from 1940 to 1941. As chairman, Stevenson worked to raise public support for military and economic aid to the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and its allies in fighting Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. Stevenson "believed Britain asAmerica's first line of defense" and "argued for a repeal of the neutrality legislation" and support for President Roosevelt's Lend-Lease programme. His efforts earned strong criticism from Colonel Robert R. McCormick

Robert Rutherford "Colonel" McCormick (July 30, 1880 – April 1, 1955) was an American lawyer, businessman and anti-war activist.

A member of the McCormick family of Chicago, McCormick became a lawyer, Republican Chicago alderman, distinguish ...

, the powerful, isolationist publisher of the ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television a ...

,'' and a leading member of the non-interventionist

Non-interventionism or non-intervention is a political philosophy or national foreign policy doctrine that opposes interference in the domestic politics and affairs of other countries but, in contrast to isolationism, is not necessarily opposed t ...

America First Committee

The America First Committee (AFC) was the foremost United States isolationist pressure group against American entry into World War II. Launched in September 1940, it surpassed 800,000 members in 450 chapters at its peak. The AFC principally supp ...

.

In 1940, Major Frank Knox

William Franklin Knox (January 1, 1874 – April 28, 1944) was an American politician, newspaper editor and publisher. He was also the Republican vice presidential candidate in 1936, and Secretary of the Navy under Franklin D. Roosevelt durin ...

, newly appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

as Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

, offered Stevenson a position as Principal Attorney and special assistant. In this capacity, Stevenson wrote speeches, represented Secretary Knox and the Navy on committees, toured the various theaters of war, and handled many administrative duties. Since Knox was largely a figurehead, there were few major roles for Stevenson. However, in early 1944 he joined a mission to Sicily and Italy for the Foreign Economic Administration to report on the country's economy. After Knox died in April 1944, Stevenson returned to Chicago where he attempted to purchase Knox's controlling interest

A controlling interest is an ownership interest in a corporation with enough voting stock shares to prevail in any stockholders' motion. A majority of voting shares (over 50%) is always a controlling interest. When a party holds less than the major ...

in the ''Chicago Daily News

The ''Chicago Daily News'' was an afternoon daily newspaper in the midwestern United States, published between 1875 and 1978 in Chicago, Illinois.

History

The ''Daily News'' was founded by Melville E. Stone, Percy Meggy, and William Doughert ...

'', but his syndicate was outbid by another party.

In 1945, Stevenson took a temporary position in the State Department, as special assistant to US Secretary of State Edward Stettinius to work with Assistant Secretary of State Assistant Secretary of State (A/S) is a title used for many executive positions in the United States Department of State, ranking below the under secretaries. A set of six assistant secretaries reporting to the under secretary for political affairs ...

Archibald MacLeish on a proposed world organization. Later that year, he went to London as Deputy United States Delegate to the Preparatory Commission of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

Organization, a position he held until February 1946. When the head of the delegation fell ill, Stevenson assumed his role. His work at the commission, and in particular his dealings with the representatives of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, resulted in appointments to the US delegations to the United Nations in 1946 and 1947.

Governor of Illinois, 1949 to 1953

In 1948, Stevenson was chosen by Jacob Arvey, leader of the powerful Chicago Democratic political organization, to be the Democratic candidate in the Illinois gubernatorial race against the incumbent Republican,

In 1948, Stevenson was chosen by Jacob Arvey, leader of the powerful Chicago Democratic political organization, to be the Democratic candidate in the Illinois gubernatorial race against the incumbent Republican, Dwight H. Green

Dwight Herbert Green (January 9, 1897 – February 20, 1958) was an American politician who served as the 30th Governor of the US state of Illinois, serving from 1941 to 1949.

From childhood to early adulthood

Green was born in Ligonier, No ...

. In an upset, Stevenson defeated Green by 572,067 votes, a record margin in Illinois gubernatorial elections.(McKeever, p. 126) President Truman carried Illinois by only 33,612 votes against his Republican opponent, Thomas E. Dewey

Thomas Edmund Dewey (March 24, 1902 – March 16, 1971) was an American lawyer, prosecutor, and politician who served as the 47th governor of New York from 1943 to 1954. He was the Republican candidate for president in 1944 and 1948: although ...

, leading a biographer to write that "Clearly, Adlai had carried the President in with him." Paul Douglas

Paul Howard Douglas (March 26, 1892 – September 24, 1976) was an American politician and Georgist economist. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as a U.S. Senator from Illinois for eighteen years, from 1949 to 1967. During his Senat ...

, a University of Chicago professor of economics, was elected senator on the same ticket.

Principal among Stevenson's achievements as Illinois governor were reforming the state police by removing political considerations from hiring practices and instituting a merit system for employment and promotion, cracking down on illegal gambling, and improving the state highways. He sought, with mixed success, to cleanse the Illinois state government of corruption; in one instance he fired the warden of the state penitentiary for overcrowding, political corruption, and incompetence that had left the prisoners on the verge of revolt, and in another instance Stevenson fired the superintendent of an institution for alcoholics when he learned that the superintendent, after receiving bribes from local tavern owners, was allowing the patients to buy drinks at local bars. Two of Stevenson's major initiatives as governor were a proposal to create a constitutional convention (called "con-con") to reform and improve the Illinois state constitution, and several crime bills that would have provided new resources and methods to fight criminal activities in Illinois. Most of the crime bills and con-con failed to pass the state legislature, much to Stevenson's chagrin. However, Stevenson did agree to support a Republican alternative to con-con called "Gateway", it passed the legislature and was approved by Illinois voters in a 1950 referendum.(McKeever, p. 136) Stevenson's push for an improved state constitution "began the process of constitutional change...and in 1969, four years after his death, the goal was achieved. It was perhaps his most important achievement as governor." The new constitution had the effect of removing the structural limitations on the growth of government in the state.

Stevenson's governorship coincided with the Second Red Scare

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of subversion and treason, especially when related to anarchism, communism and socialism, and especially when done in a public and attention-grabbing manner.

The term origina ...

, and during his term, the Illinois state legislature passed a bill that would have "made it a felony to belong to any subversive group", and would have required "a loyalty oath of public employees and candidates for office." Stevenson vetoed the bill. In his public message regarding the veto, Stevenson wrote "Does anyone seriously think that a real traitor will hesitate to sign a loyalty oath? Of course not. Really dangerous subversives and saboteurs will be caught by careful, constant, professional investigation, not by pieces of paper. The whole notion of loyalty inquisitions is a natural characteristic of the police state, not of democracy. I know full well this veto will be distorted and misunderstood...I know that to veto this bill in this period of grave anxiety will be unpopular with many. But I must, in good conscience, protest against any unnecessary suppression of our ancient rights as free men...we will win the contest of ideas that afflicts the world not by suppressing those rights, but by their triumph."

Stevenson proved to be a popular public speaker, gaining a national reputation as an intellectual, with a self-deprecating sense of humor to match. One example came when the Illinois legislature passed a bill (supported by bird lovers) declaring that cats roaming unescorted was a public nuisance. Stevenson vetoed the bill, and sent this public message regarding the veto: "It is in the nature of cats to do a certain amount of unescorted roaming...the problem of cat versus bird is as old as time. If we attempt to solve it by legislation who knows but what we may be called upon to take sides as well in the age old problem of dog versus cat, bird versus bird, or even bird versus worm. In my opinion, the State of Illinois and its local governing bodies already have enough to do without trying to control feline delinquency. For these reasons, and not because I love birds the less or cats the more, I veto and withhold my approval from Senate Bill No. 93."

On June 2, 1949, Stevenson privately gave a sworn deposition as a character witness for Alger Hiss, a former State Department official who was later found to be a spy for the Soviet Union.(McKeever, pp. 144–145) Stevenson had infrequently worked with Hiss, first in the legal division of the Agricultural Adjustment Administration in 1933, and then in 1945, 1946, and 1947 on various United Nations projects, but he was not a close friend or associate of him. In the deposition, Stevenson testified that the reputation of Hiss for integrity, loyalty, and veracity was good.(McKeever, p. 145) In 1950, Hiss was found guilty of perjury on the spying charges. Stevenson's deposition, according to his biographer Porter McKeever, would later be used in the 1952 presidential campaign by Senators Joseph McCarthy and Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

to "inflame public opinion and attack Adlai as 'soft on communism'." In the 1952 campaign, Senator Nixon would claim that Stevenson's "defense of Hiss" reflected such "poor judgment" on his part that "doubt was cast about Adlai's capacity to govern." In a 1952 appearance on NBC's ''Meet the Press

''Meet the Press'' is a weekly American television news/interview program broadcast on NBC. It is the longest-running program on American television, though the current format bears little resemblance to the debut episode on November 6, 1947. ' ...

'', Stevenson responded to a question about his deposition for Hiss by saying "I'm a lawyer. I think that one of the most fundamental responsibilities...particularly of lawyers, is to give testimony in a court of law, to give it honestly and willingly, and it will be a very unhappy day for Anglo-Saxon justice when a man, even in public life, is too timid to state what he knows and what he has heard about a defendant in a criminal trial for fear that defendant might later be convicted. That would to me be the ultimate timidity."

1952 presidential bid

Early in 1952, while Stevenson was still governor of Illinois, President

Early in 1952, while Stevenson was still governor of Illinois, President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

decided that he would not seek another term as president. Instead, Truman met with Stevenson in Washington and proposed that Stevenson seek the Democratic nomination for president; Truman promised him his support if he did so. Stevenson at first hesitated, arguing that he was committed to running for a second gubernatorial term in Illinois. However, a number of his friends and associates (such as George Wildman Ball) quietly began organizing a "draft Stevenson" movement for president; they persisted in their activity even when Stevenson (both publicly and privately) told them to stop. When Stevenson continued to state that he was not a candidate, President Truman and the Democratic Party leadership looked for other prospective candidates. However, each of the other main contenders had a major weakness. Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee won most of the presidential primaries and entered the 1952 Democratic National Convention

The 1952 Democratic National Convention was held at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois from July 21 to July 26, 1952, which was the same arena the Republicans had gathered in a few weeks earlier for their national convention f ...

with the largest number of delegates, but he was unpopular with President Truman and other prominent Democrats. In 1950, Kefauver had chaired a Senate committee that traveled to several large cities and held televised hearings into organized crime. The hearings revealed connections between organized-crime syndicates and big-city Democratic political organizations, which led Truman and other Democratic leaders to oppose Kefauver's bid for the nomination: "a machine politician and proud of it, ruman Ruman may refer to:

* Ruman (surname)

* Ruman Ahmed, Bangladeshi cricketer

* Operation RUMAN

See also

* Rumman (disambiguation)

* Rumana (disambiguation)

*Tell Ruman

Tell Ruman Tahtani ( ar, تل رمان), also known as Mazra (), is a village ...

had no use for reformers who blackened the names of fellow Democrats." Truman favored U.S. diplomat W. Averell Harriman, but he had never held elective office and was inexperienced in national politics. Truman next turned to his vice-president, Alben Barkley

Alben William Barkley (; November 24, 1877 – April 30, 1956) was an American lawyer and politician from Kentucky who served in both houses of Congress and as the 35th vice president of the United States from 1949 to 1953 under Presid ...

, but at 74 years of age he was dismissed as being too old by labor union leaders. Senator Richard Russell Jr.

Richard Brevard Russell Jr. (November 2, 1897 – January 21, 1971) was an American politician. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as the 66th Governor of Georgia from 1931 to 1933 before serving in the United States Senate for alm ...

of Georgia was popular in the South, but his support of racial segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

and opposition to civil rights for blacks made him unacceptable to Northern and Western Democrats. In the end Stevenson, despite his reluctance to run, remained the most attractive candidate heading into the 1952 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

1952 Republican National Convention

The 1952 Republican National Convention was held at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois from July 7 to 11, 1952, and nominated the popular general and war hero Dwight D. Eisenhower of New York, nicknamed "Ike," for president an ...

, which had been held in Chicago in the same coliseum two weeks earlier. Stevenson described the achievements of the Democratic Party under Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman, but noted "our Republican friends have said it was all a miserable failure. For almost a week pompous phrases marched over this landscape in search of an idea, and the only idea that they found was that the two great decades of progress...were the misbegotten spawn of bungling, of corruption, of socialism, of mismanagement, of waste and worse...after listening to this everlasting procession of epithets about our arty'smisdeeds I was even surprised the next morning when the mail was delivered on time. But we Democrats were by no means the only victims here. First they epublicansslaughtered each other, and then they went after us...perhaps the proximity of the stockyards accounts for the carnage."

Following this speech, the Illinois delegation (led by Jacob Arvey) announced that they would place Stevenson's name in nomination, and Stevenson called President Truman to ask if "he would be embarrassed" if Stevenson formally announced his candidacy for the nomination. Truman told Stevenson "I have been trying since January to get you to say that. Why should it embarrass me?"(Manchester, p. 622) Kefauver led on the first ballot, but was well below the vote total he needed to win. Stevenson gradually gained strength until he was nominated on the third ballot. The 1952 Democratic National Convention was the last political convention of either major party to require more than one ballot to nominate a presidential candidate.

Historian John Frederick Martin says party leaders selected him because he was "more moderate on civil rights than Estes Kefauver, yet nonetheless acceptable to labor and urban machines—so a coalition of southern, urban, and labor leaders fell in behind his candidacy in Chicago". Stevenson's 1952 running mate was Senator John Sparkman

John Jackson Sparkman (December 20, 1899 – November 16, 1985) was an American jurist and politician from the state of Alabama. A Southern Democrat, Sparkman served in the United States House of Representatives from 1937 to 1946 and the United St ...

of Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,765 ...

.

Stevenson accepted the Democratic nomination with an acceptance speech that, according to contemporaries, "electrified the delegates:"

When the tumult and the shouting die, when the bands are gone and the lights are dimmed, there is the stark reality of responsibility in an hour of history haunted with those gaunt, grim specters of strife, dissension, and materialism at home, and ruthless, inscrutable, and hostile power abroad. The ordeal of the twentieth century – the bloodiest, most turbulent age of the Christian era – is far from over. Sacrifice, patience, understanding, and implacable purpose may be our lot for years to come. ... Let's talk sense to the American people! Let's tell them the truth, that there are no gains without pains, that we are now on the eve of great decisions.Although Stevenson's eloquent oratory and thoughtful, stylish demeanor impressed many intellectuals, journalists, political commentators, and members of the nation's academic community, the Republicans and some working-class Democrats ridiculed what they perceived as his indecisive, aristocratic air. During the 1952 campaign Stewart Alsop, a powerful Connecticut Republican, labeled Stevenson an "egghead", based on his baldness and intellectual air. His brother, the influential newspaper columnist Joe Alsop, used the word to underscore Stevenson's difficulty in attracting working-class voters, and the nickname stuck.(Halberstam, p. 235) Stevenson himself made fun of his "egghead" nickname; in one speech he joked " eggheads of the world unite, you have nothing to lose but your yolks!" In his campaign speeches Stevenson strongly criticized the Communist-hunting tactics of Senator Joseph McCarthy, labeling "McCarthy's kind of patriotism as a disgrace" and ridiculing right-wing Republicans "who hunt Communists in the Bureau of Wildlife and Fisheries while hesitating to aid the gallant men and women who are resisting the real thing in the front lines of Europe and Asia...they are finally the men who seemingly believe that we can confound the Kremlin by frightening ourselves to death." In return, Senator McCarthy stated in a speech that "he would like to get on the Stevenson campaign trail with a club and thereby make a good and loyal American out of the governor". In the 1952 campaign, Stevenson also developed a strong dislike for Richard M. Nixon, then the GOP vice-presidential candidate. "Adlai literally loathed Nixon. No other person aroused such disgust; not even Joseph McCarthy...Friends who often wished he could be more of a hater were awed at the strength of his distaste for Nixon." A biographer wrote that "for Stevenson, Nixon was an ambitious, unprincipled partisan who craved winning, the exact personification of what was wrong with modern American politics... or StevensonNixon was an entirely plastic politician...Nixon was Stevenson's complete villain. Others sensed the potential for immorality that led to Nixon's humiliating resignation in 1974, but Stevenson was among the first." During the 1952 campaign Stevenson often used his wit to attack Nixon, and once stated that Nixon "was the kind of politician who would cut down a redwood tree, and then mount the stump and make a speech for reeconservation". The journalist

David Halberstam

David Halberstam (April 10, 1934 April 23, 2007) was an American writer, journalist, and historian, known for his work on the Vietnam War, politics, history, the Civil Rights Movement, business, media, American culture, Korean War, and late ...

later wrote that "Stevenson asan elegant campaigner who raised the political discourse" and that in 1952 "Stevenson reinvigorated he Democratic Partyand made it seem an open and exciting place for a generation of younger Americans who might otherwise never have thought of working for a political candidate." During the campaign, a photograph revealed a hole in the sole of Stevenson's right shoe. This became a symbol of Stevenson's frugality and earthiness. The Eisenhower campaign attempted to use the symbol of the shoe with a hole to criticize Stevenson in advertising, to which Stevenson said, “Better a hole in the shoe than a hole in the head.” Photographer William M. Gallagher of the ''Flint Journal

''The Flint Journal'' is a quad-weekly newspaper based in Flint, Michigan, owned by Booth Newspapers, a subsidiary of Advance Publications. Published Tuesdays, Thursdays, Fridays and Sundays, it serves Genesee, Lapeer and Shiawassee Countie ...

'' won the 1953 Pulitzer prize The following are the Pulitzer Prizes for 1953.

Journalism awards

*Public Service:

**'' Whiteville (N.C.) News Reporter'' and '' Tabor City (N.C.) Tribune'', two weekly newspapers, for their successful campaign against the Ku Klux Klan, waged o ...

on the strength of the image.

Stevenson did not use television as effectively as his Republican opponent, war hero Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

, and was unable to rally the New Deal voting coalition for one last hurrah. Historian Richard Aldous wrote "Occasionally persuasive, tevensonwas rarely compelling and, unlike Eisenhower, he lacked any kind of rapport or common touch with large crowds. He also failed to respond quickly enough to Eisenhower's pioneering use of TV. Both candidates resisted the new medium at first, but Ike relented sooner. He used "Mad Men" advertising executive Rosser Reeves of the Ted Bates agency to create brilliant thirty-second TV spots. Ironically, Stevenson came across well on TV, but his highfalutin nature caused him to minimize it in the campaign. "This is the worst thing I've ever heard of," he scoffed, "selling the presidency like breakfast cereal!" That attitude left him behind the curve." On election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has opera ...

day, Eisenhower won the national popular vote by 55% to 45%. Stevenson lost heavily outside the Solid South

The Solid South or Southern bloc was the electoral voting bloc of the states of the Southern United States for issues that were regarded as particularly important to the interests of Democrats in those states. The Southern bloc existed especial ...

; he carried only nine states and lost the Electoral College vote 442 to 89. In his concession speech on election night, Stevenson said: "Someone asked me...how I felt, and I was reminded of a story that a fellow townsman of ours used to tell – Abraham Lincoln. He said he felt like the little boy who had stubbed his toe in the dark. He said that he was too old to cry, but it hurt too much to laugh."

Biographer Jean H. Baker summarized Stevenson's 1952 campaign: "Uncomfortable with the carnival side of elections, Stevenson tried to be a man for the people, not of them; a man of reason talking sense, not manipulation or sentiment." "Liberals...were attracted to the Illinois governor because he firmly opposed McCarthyism, ndthey also appreciated Stevenson because of his style...he had clearly dissociated himself, as did many Americans, from the plebians. Stevenson dramatized the complex feelings of educated elites, some of whom came to adore him not because he was a liberal, but because he was not...he spoke a language that set apart from average Americans an increasingly college-educated population. His approach to voters as rational participants in a process that depended on weighing the issues attracted reformers, intellectuals, and middle-class women with time and money (the "Shakespeare vote", joked one columnist). Or as one enthralled voter wrote "You were too good for the American people." "Adlai Stevenson ended the 1952 campaign with an adoring group of Stevensonites. Articulate and loyal...they would soon create the Stevenson legend and make the Man from Libertyville a counterhero to President Eisenhower, whom they would portray as inept and banal."

1953 World Tour and 1954 elections

Following his defeat, Stevenson in 1953 made a well-publicized world tour through Asia, the Middle East and Europe, writing about his travels for '' Look'' magazine. His political stature as head of the Democratic Party gave him access to many foreign leaders and dignitaries. He was elected a Fellow of the

Following his defeat, Stevenson in 1953 made a well-publicized world tour through Asia, the Middle East and Europe, writing about his travels for '' Look'' magazine. His political stature as head of the Democratic Party gave him access to many foreign leaders and dignitaries. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

in 1953. In the 1954 off-year elections Stevenson took a leading role in campaigning for Democratic congressional and gubernatorial candidates around the nation. When the Democrats won control of both houses of Congress and picked up nine gubernatorial seats it "put Democrats around the country in Stevenson's debt and greatly strengthened his position as his party's leader."

1956 presidential bid

1956 Democratic National Convention

The 1956 Democratic National Convention nominated former Governor Adlai Stevenson of Illinois for president and Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee for vice president. It was held in the International Amphitheatre on the South Side of Chic ...

in Chicago, former President Truman endorsed Governor Harriman, to Stevenson's dismay, but the blow was softened by former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

's continued enthusiastic support. Stevenson easily defeated Harriman on the first ballot, winning his second Democratic presidential nomination.(McKeever, p. 376) He was aided by strong support from younger delegates, who were said to form the core of the " New Politics" movement. In a bid to raise enthusiasm for the Democratic ticket, Stevenson made the unusual decision to leave the selection of his running mate up to the convention delegates. This set off a frantic scramble among several prominent Democrats to win the vice-presidential nomination, including Kefauver, Senator Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing Mi ...

, and Senator John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

. After fending off a surprisingly strong challenge from Kennedy, Kefauver narrowly won the vice-presidential nomination on the second ballot.(McKeever, p. 377) In his acceptance speech, Stevenson spoke of his plan for a "New America", which included extending New Deal programs to "areas of education, health, and poverty". He also criticized Republicans for trying to "merchandise candidates like breakfast cereal".

Following his nomination, Stevenson waged a vigorous presidential campaign

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese fu ...

, delivering 300 speeches and traveling ; he crisscrossed the nation three times before the election in November.(Baker, p. 364) Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925June 6, 1968), also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 64th United States Attorney General from January 1961 to September 1964, ...

traveled with the Stevenson campaign, hoping to "take home some lessons on how to manage a presidential campaign". Kennedy was deeply disillusioned by Stevenson's campaign, later saying that "I thought it was ghastly. It was poorly organized...my feeling was that he had no rapport with his audience – no comprehension of what campaigning required, no ability to make decisions...In 1952 I had been crazy about him...Then I spent six weeks with him on the campaign and he destroyed it all." Kennedy voted for Eisenhower in November. For their part, Stevenson and many of his aides resented Kennedy's attitude during his stay with the campaign; Stevenson friend and aide George W. Ball recalled "My impression was that Bobby was a very surly and arrogant young man...he wasn't doing any good for Adlai. I don't know why we had him along." The tension that developed between Stevenson and Robert Kennedy would have significant consequences for the 1960 presidential campaign, and for Stevenson's relationships with both John and Robert Kennedy during President Kennedy's administration.

Against the advice of many of his political advisers, Stevenson insisted on calling for an international ban to aboveground nuclear weapons tests, and for an end to the military draft. Despite strong criticism from President Eisenhower and other leading Republicans, such as Vice-president Nixon and former New York Governor Thomas Dewey, that his proposals were naive and would benefit the Soviet Union in the cold war, Stevenson held his ground, saying in various speeches that "Earth's atmosphere is contaminated from week to week by exploding hydrogen bombs...We don't want to live forever in the shadow of a radioactive mushroom cloud... ndgrowing children are the principal potential sufferers" of increased strontium 90

Strontium-90 () is a radioactive isotope of strontium produced by nuclear fission, with a half-life of 28.8 years. It undergoes β− decay into yttrium-90, with a decay energy of 0.546 MeV. Strontium-90 has applications in medicine and ...

in the atmosphere. In the end, Stevenson's push to ban atmospheric nuclear bomb tests "cost him dearly in votes", yet "Adlai finally won the verdict", as Eisenhower suspended aboveground nuclear tests in 1958, President Kennedy would sign the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) is the abbreviated name of the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, which prohibited all test detonations of nuclear weapons except for those conducted ...

into law in 1963, and President Nixon would end the military draft in 1973.

Civil rights was emerging rapidly as a major political issue. Stevenson urged caution and warned against aggressive enforcement of the Supreme Court's ''Brown'' decision in order to gain Southern white support. Kotlowski writes:

Liberal Democrats, too, flinched before Brown. Adlai E. Stevenson, front-runner for the party's presidential nomination in 1956, urged the government to "proceed gradually" on school desegregation in deference to the South's long-held "traditions". Stevenson backed integration but opposed using armed personnel to enforce Brown....It certainly helped. Stevenson carried most of Dixie in the fall campaign but received just 61 percent of the black vote, low for a Democrat, and lost the election to Eisenhower by a landslide.His views on racial progress were described after his death by his longtime companion Marietta Tree as: "He thought of all Negroes as being loveable old family retainers and not as individuals like you and me who were longing to get educated and who had aspirations and dreams just like the rest of us. I think this took him a long time to get over--the fact that they really indeed not only were created equal; they wanted equality of opportunity and wanted it now. It was hard for him to understand the urgency." While President Eisenhower suffered heart problems, the economy enjoyed robust health. Stevenson's hopes for victory were dashed when, in October, Eisenhower's doctors gave him a clean bill of health and the

Suez

Suez ( ar, السويس '; ) is a seaport city (population of about 750,000 ) in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez (a branch of the Red Sea), near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal, having the same bou ...

and Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

crises erupted simultaneously. The public was not convinced that a change in leadership was needed. Stevenson lost his second bid for the presidency by a landslide, winning only 42% of the popular vote and 73 electoral votes from just seven states, all except Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

in the solid Democratic South.

Early in 1957, Stevenson resumed law practice

In its most general sense, the practice of law involves giving legal advice to clients, drafting legal documents for clients, and representing clients in legal negotiations and court proceedings such as lawsuits, and is applied to the professi ...

, allying himself with Judge Simon H. Rifkind to create a law firm based in Washington, D.C. (Stevenson, Paul, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison), and a second firm in Chicago (Stevenson, Rifkind & Wirtz). Both law firms were related to New York City's Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison

Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP (known as Paul, Weiss) is an American multinational law firm headquartered on Sixth Avenue in New York City. By profits per equity partner, it is the fifth most profitable law firm in the world.

...

. Stevenson's associates in the new law firm included Willard Wirtz

William Willard Wirtz Jr. (March 14, 1912 – April 24, 2010) was a U.S. administrator, cabinet officer, attorney, and law professor. He served as the Secretary of Labor between 1962 and 1969 under the administrations of Presidents John F ...

, William McCormick Blair Jr., and Newton N. Minow

Newton Norman Minow (born January 17, 1926) is an American attorney and former Chair of the Federal Communications Commission. He is famous for his speech referring to television as a " vast wasteland". While still maintaining a law practice, Mi ...

; each of these men later served in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. He also accepted an appointment, along with other prominent Democrats, to the new Democratic Advisory Council, which "pursued an aggressive line in attacking the epublicanEisenhower administration and in developing new Democratic policies". He was also employed part-time

Part-time can refer to:

* Part-time job, a job that has fewer hours a week than a full-time job

* Part-time student, a student, usually in higher education, who takes fewer course credits than a full-time student

* Part Time

Part Time (styliz ...

by the ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various t ...

'' as a legal consultant.

1960 presidential campaign and appointment as UN Ambassador

In early 1960 Stevenson announced that he would not seek a third Democratic presidential nomination, but would accept a draft. One of his closest friends told a journalist that "Deep down, he wants he Democratic nomination But he wants the emocraticConvention to come to him, he doesn't want to go to the Convention." In May 1960 SenatorJohn F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

, who was actively campaigning for the Democratic nomination, visited Stevenson at his Libertyville home. Kennedy asked Stevenson for a public endorsement of his candidacy; in exchange Kennedy promised, if elected, to appoint Stevenson as his Secretary of State. Stevenson turned down the offer, which strained relations between the two men.(Dallek, p. 94) At the 1960 Democratic National Convention

The 1960 Democratic National Convention was held in Los Angeles, California, on July 11–15, 1960. It nominated Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts for president and Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas for vice president.

In ...

in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

, Stevenson's admirers, led by Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

, Agnes Meyer, and such Hollywood celebrities as Dore Schary

Isadore "Dore" Schary (August 31, 1905 – July 7, 1980) was an American playwright, director, and producer for the stage and a prolific screenwriter and producer of motion pictures. He directed just one feature film, '' Act One'', the film bio ...

and Henry Fonda

Henry Jaynes Fonda (May 16, 1905 – August 12, 1982) was an American actor. He had a career that spanned five decades on Broadway and in Hollywood. He cultivated an everyman screen image in several films considered to be classics.

Born and ra ...

, vigorously promoted him for the nomination, even though he was not an announced candidate. JFK's campaign manager, his brother Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925June 6, 1968), also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 64th United States Attorney General from January 1961 to September 1964, ...

, reportedly threatened Stevenson in a meeting, telling him that unless he agreed to place his brother's name in nomination "you are through". Stevenson refused and ordered him out of his hotel room. In letters to friends, Stevenson described both John and Robert Kennedy as "cold and ruthless", referred to Robert Kennedy as the "Black Prince", and expressed his belief that JFK, "though bright and able, was too young, too unseasoned, to be President; he pushed too hard, was in too much of a hurry; he lacked the wisdom of humility... tevenson feltthat both Kennedy and the nation would benefit from a postponement of his ambition."

The night before the balloting Stevenson began working actively for the nomination, calling the leaders of several state delegations to ask for their support. The key call went to Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley

Richard Joseph Daley (May 15, 1902 – December 20, 1976) was an American politician who served as the Mayor of Chicago from 1955 and the chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party Central Committee from 1953 until his death. He has been cal ...

, the leader of the Illinois delegation. The delegation had already voted to give Kennedy 59.5 votes to Stevenson's 2, but Stevenson told Daley that he now wanted the Democratic nomination, and asked him if the "delegates' vote might merely indicate they thought he was not a candidate".(Martin, p. 526) Daley told Stevenson that he had no support in the delegation. Stevenson then "asked if this meant no support in fact or no support because the delegates thought he was not a candidate. Daley replied that Stevenson had no support." According to Stevenson biographer John Bartlow Martin

John Bartlow Martin (4 August 1915, in Hamilton, Ohio – 3 January 1987, in Highland Park, Illinois) was an American diplomat, author of 15 books, ambassador, and speechwriter and confidant to many Democratic politicians including Adlai Steve ...

, the phone conversation with Daley "was the real end of the 960

Year 960 ( CMLX) was a leap year starting on Sunday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* Summer – Siege of Chandax: A Byzantine fleet with an expeditionary force (co ...

Stevenson candidacy...if he could not get the support of his home state his candidacy was doomed". However, Stevenson continued to work for the nomination the next day, fulfilling what he felt were obligations to old friends and supporters such as Eleanor Roosevelt and Agnes Meyer. Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota delivered an impassioned nominating speech for Stevenson, urging the convention to not "reject the man who has made us proud to be Democrats. Do not leave this prophet without honor in his own party."(Baker, p. 403) However, Kennedy won the nomination on the first ballot with 806 delegate votes; Stevenson finished in fourth place with 79.5 votes.

Once Kennedy won the nomination, Stevenson, always an enormously popular public speaker, campaigned actively for him. Due to his two presidential nominations and previous United Nations experience, Stevenson perceived himself an elder statesman and the natural choice for Secretary of State. However, according to historian Robert Dallek

Robert A. Dallek (born May 16, 1934) is an American historian specializing in the presidents of the United States, including Franklin D. Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Richard Nixon. He retired as a history professor at Bost ...

, "neither Jack nor Bobby ennedythought all that well of Stevenson...they saw him as rather prissy and ineffective. tevensonnever met their standard of tough-mindedness." Stevenson's refusal to publicly endorse Kennedy before the Democratic Convention was something that Kennedy "couldn't forgive", with JFK telling a Stevenson supporter after the election, "I'm not going to give him anything." The prestigious post of Secretary of State went instead to the (then) little-known Dean Rusk

David Dean Rusk (February 9, 1909December 20, 1994) was the United States Secretary of State from 1961 to 1969 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, the second-longest serving Secretary of State after Cordell Hull from the F ...

. However, "although Jack and Bobby would have been just as happy to freeze Stevenson out of the administration, they felt compelled to offer him something" due to his continued support from progressive Democrats. President Kennedy offered Stevenson the choice of becoming ambassador to Britain, attorney general (a post that eventually went to Robert Kennedy), or United States Ambassador to the United Nations. Stevenson accepted the latter position.

Many years later it was revealed that during the campaign Stevenson was approached by Soviet Ambassador Menshikov who offered Soviet financial and public relations help to assist him in getting elected if he decided to run. Stevenson flatly rejected the Soviet offer telling Menshikov that he, "considered the offer of such assistance highly improper, indiscreet and dangerous to all concerned". Stevenson then reported the incident directly to President Eisenhower.(Martin. Adlai Stevenson and the World.)

Ambassador to the United Nations, 1961 to 1965

At the United Nations Stevenson worked hard to support

At the United Nations Stevenson worked hard to support U.S. foreign policy

The officially stated goals of the foreign policy of the United States of America, including all the bureaus and offices in the United States Department of State, as mentioned in the ''Foreign Policy Agenda'' of the Department of State, are ...

, even when he personally disagreed with some of President Kennedy's actions. However, he was often seen as an outsider in the Kennedy administration, with one historian noting "everyone knew that Stevenson's position was that of a bit player". Kennedy told his adviser Walt Rostow

Walt Whitman Rostow (October 7, 1916 – February 13, 2003) was an American economist, professor and political theorist who served as National Security Advisor to President of the United States Lyndon B. Johnson from 1966 to 1969.

Rostow worked ...

that "Stevenson wouldn't be happy as president. He thinks that if you talk long enough you get a soft option and there are very few soft options as president."

Bay of Pigs incident

In April 1961 Stevenson suffered the greatest humiliation of his diplomatic career in theBay of Pigs invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called ''Invasión de Playa Girón'' or ''Batalla de Playa Girón'' after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in 1961 by Cuban exiles, covertly fin ...

. After hearing rumors that "a lot of refugees wanted to go back and overthrow Castro", Stevenson voiced his skepticism about an invasion, but "he was kept on the fringes of the operation, receiving...nine days before the invasion, only an unduly vague briefing by Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.

Arthur Meier Schlesinger Jr. (; born Arthur Bancroft Schlesinger; October 15, 1917 – February 28, 2007) was an American historian, social critic, and public intellectual. The son of the influential historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. and a s ...

" and the CIA.(Dallek, p. 142) Senior CIA official Tracy Barnes

Charles Tracy Barnes (August 2, 1911 – February 18, 1972) was a senior staff member at the United States' Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), serving as principal manager of CIA operations in the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état and the 1961 Bay of P ...