Adams–Onís Treaty on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Spanish Cession, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p. 168. was a

In 1521, the Spanish Empire created the ''Virreinato de Nueva España'' (Viceroyalty of New Spain) to govern its conquests in the Caribbean, North America, and later the Pacific Ocean. In 1682, La Salle claimed Louisiana for France. For the Spanish Empire, this was an intrusion into the northeastern frontier of New Spain. In 1691, Spain created the Province of Tejas in an attempt to inhibit French settlement west of the Mississippi River. Fearing the loss of his American territories in the Seven Years' War, King Louis XV of France ceded Louisiana to King Charles III of Spain with the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau in 1762. The Treaty of Paris of 1763 split Louisiana with the portion east of the Mississippi River (except for

In 1521, the Spanish Empire created the ''Virreinato de Nueva España'' (Viceroyalty of New Spain) to govern its conquests in the Caribbean, North America, and later the Pacific Ocean. In 1682, La Salle claimed Louisiana for France. For the Spanish Empire, this was an intrusion into the northeastern frontier of New Spain. In 1691, Spain created the Province of Tejas in an attempt to inhibit French settlement west of the Mississippi River. Fearing the loss of his American territories in the Seven Years' War, King Louis XV of France ceded Louisiana to King Charles III of Spain with the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau in 1762. The Treaty of Paris of 1763 split Louisiana with the portion east of the Mississippi River (except for

The British government claimed the region west of the Continental Divide between the undefined borders of

The British government claimed the region west of the Continental Divide between the undefined borders of

/ref> The United States claimed essentially the same region on the basis of (1) Robert Gray's Columbia River expedition, the voyage of Robert Gray up the

On 16 July 1741, the crew of the Imperial Russian Navy ship ''

On 16 July 1741, the crew of the Imperial Russian Navy ship ''

The Spanish Empire claimed all lands west of the Continental Divide throughout the Americas.The claim of Spain to all lands west of the Continental Divide in the Americas dated to the

The Spanish Empire claimed all lands west of the Continental Divide throughout the Americas.The claim of Spain to all lands west of the Continental Divide in the Americas dated to the

The treaty, consisting of 16 articles was signed in Adams' State Department office at Washington, on February 22, 1819, by

The treaty, consisting of 16 articles was signed in Adams' State Department office at Washington, on February 22, 1819, by

The treaty was ratified by Spain in 1820, and by the United States in 1821 (during the time that Spain and Mexico were engaged in the prolonged

The treaty was ratified by Spain in 1820, and by the United States in 1821 (during the time that Spain and Mexico were engaged in the prolonged  Another dispute occurred after Texas joined the Union. The treaty stated that the boundary between the French claims on the north and the Spanish claims on the south was Rio Roxo de Natchitoches (Red River) until it reached the 100th meridian, as noted on the John Melish map of 1818. But, the 100th meridian on the Melish map was marked some east of the true 100th meridian, and the Red River forked about east of the 100th meridian. Texas claimed the land south of the North Fork, and the United States claimed the land north of the South Fork (later called the

Another dispute occurred after Texas joined the Union. The treaty stated that the boundary between the French claims on the north and the Spanish claims on the south was Rio Roxo de Natchitoches (Red River) until it reached the 100th meridian, as noted on the John Melish map of 1818. But, the 100th meridian on the Melish map was marked some east of the true 100th meridian, and the Red River forked about east of the 100th meridian. Texas claimed the land south of the North Fork, and the United States claimed the land north of the South Fork (later called the

online

* . ;Sources

Avalon Project – Treaty Text

Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture – Adams–Onís Treaty

{{DEFAULTSORT:Adams-Onis Treaty 1819 treaties Boundary treaties New Spain Missouri Territory Spanish Florida Spanish Texas Treaties of the Spanish Empire Treaties of the United States Mexico–United States border 1819 in New Spain 1819 in the United States 1819 in Nueva California 16th United States Congress History of United States expansionism Pre-statehood history of Florida Spain–United States relations Red River of the South February 1819 Purchased territories Eponymous treaties Sabine River (Texas–Louisiana)

treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between sovereign states and/or international organizations that is governed by international law. A treaty may also be known as an international agreement, protocol, covenant, convention ...

between the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

in 1819 that ceded Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

to the U.S. and defined the boundary between the U.S. and Mexico (New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

). It settled a standing border dispute between the two countries and was considered a triumph of American diplomacy

Diplomacy is the communication by representatives of State (polity), state, International organization, intergovernmental, or Non-governmental organization, non-governmental institutions intended to influence events in the international syste ...

. It came during the successful Spanish American wars of independence against Spain.

Florida had become a burden to Spain, which could not afford to send settlers or staff garrisons, so Madrid decided to cede the territory to the United States in exchange for settling the boundary dispute along the Sabine River in Spanish Texas. The treaty established the boundary of U.S. territory and claims through the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in great-circle distance, straight-line distance from the northernmost part of Western Can ...

and west to the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

, in exchange for Washington paying residents' claims against the Spanish government up to a total of $5 million Spanish dollars (purchasing power ) and relinquishing the U.S. claims on parts of Spanish Texas west of the Sabine River and other Spanish areas, under the terms of the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

.

The treaty remained in full effect for only 183 days: from February 22, 1821, to August 24, 1821, when Spanish military officials signed the Treaty of Córdoba acknowledging the independence of Mexico; Spain repudiated that treaty, but Mexico effectively took control of Spain's former colony. The Treaty of Limits between Mexico and the United States, signed in 1828 and effective in 1832, recognized the border defined by the Adams–Onís Treaty as the boundary between the two nations.

History

The Adams–Onís Treaty was negotiated byJohn Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

, the Secretary of State under U.S. President James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American Founding Father of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. He was the last Founding Father to serve as presiden ...

, and the Spanish minister plenipotentiary (diplomatic envoy) Luis de Onís y González-Vara, during the reign of King Ferdinand VII.

Florida

Spain had long rejected repeated American efforts to purchase Florida. But by 1818, Spain was facing a troubling colonial situation in which the cession of Florida made sense. Spain had been exhausted by thePeninsular War

The Peninsular War (1808–1814) was fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Kingdom of Portugal, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French ...

(1807–1814) against Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

in Europe and needed to rebuild its credibility and presence in its colonies. Revolutionaries in Central America and South America had been waging wars of independence since 1810. Spain was unwilling to invest further in Florida, encroached on by American settlers, and it worried about the border between New Spain (a large area including today's Mexico, Central America, and much of the current U.S. western states) and the United States. With minor military presence in Florida, Spain was not able to restrain the Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, ...

warriors who routinely crossed the border and raided American villages and farms, as well as protected southern slave refugees from slave owners and traders of the southern United States.Weeks

The United States from 1810 to 1813 annexed and then invaded most of West Florida (already independent as the Republic of West Florida west of the Pearl River) up to the Perdido River (modern border river between the states of Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

and Florida), claiming that the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

covered West Florida also.Marshall (1914), p. 11. General James Wilkinson invaded and occupied Mobile during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

and the Spanish never returned to West Florida west of the Perdido River.

The State of Muskogee (1799–1803) demonstrated Spain's inability to control the interior of East Florida, at least '' de facto''; the Spanish presence had been reduced to the capital ( San Agustín) and other coastal cities, while the interior belonged to the Seminole nation.

While fighting escaped African-American slaves, outlaws, and Native Americans in U.S.-controlled Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

during the First Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were a series of three military conflicts between the United States and the Seminoles that took place in Florida between about 1816 and 1858. The Seminoles are a Native American nation which co ...

, American General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

had pursued them into Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida () was the first major European land-claim and attempted settlement-area in northern America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and th ...

. He built Fort Scott, at the southern border of Georgia (i.e., the U.S.), and used it to destroy the Negro Fort in northwest Florida, whose existence was perceived as an intolerably disruptive risk by Georgia plantation owners.

To stop the Seminole based in East Florida from raiding Georgia settlements and offering havens for runaway slaves, the U.S. Army led increasingly frequent incursions into Spanish territory. This included the 1817–1818 campaign by Andrew Jackson that became known as the First Seminole War, after which the U.S. effectively seized control of Florida; albeit for purposes of lawful government and administration in Georgia and not for the outright annexation of territory for the U.S. Adams said the U.S. had to take control because Florida (along the border of Georgia and Alabama Territory) had become "a derelict open to the occupancy of every enemy, civilized or savage, of the United States, and serving no other earthly purpose than as a post of annoyance to them". Spain asked for British intervention, but London declined to assist Spain in the negotiations. Some of President Monroe's cabinet demanded Jackson's immediate dismissal for invading Florida, but Adams realized that his success had given the U.S. a favorable diplomatic position. Adams was able to negotiate very favorable terms.

Louisiana

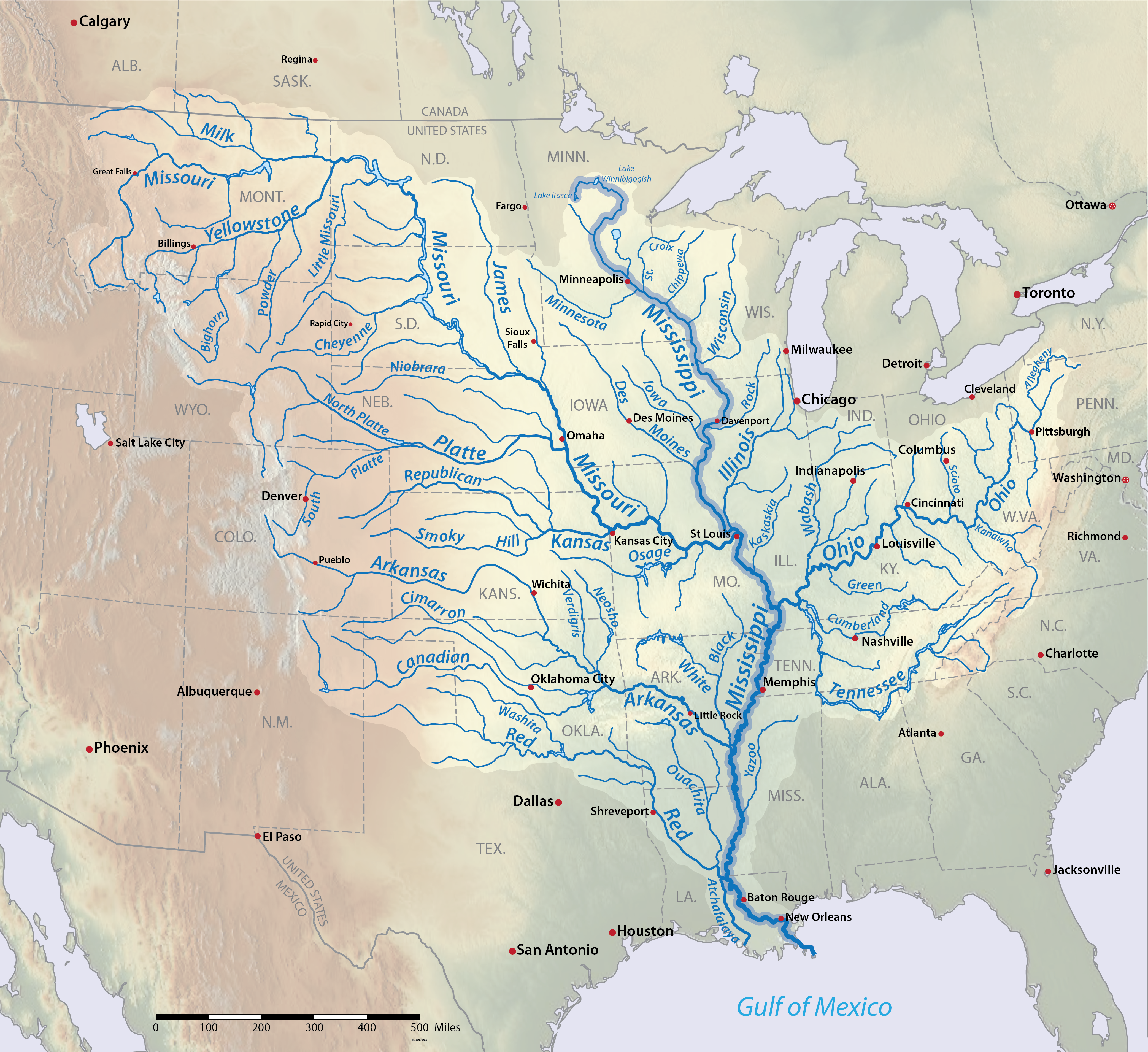

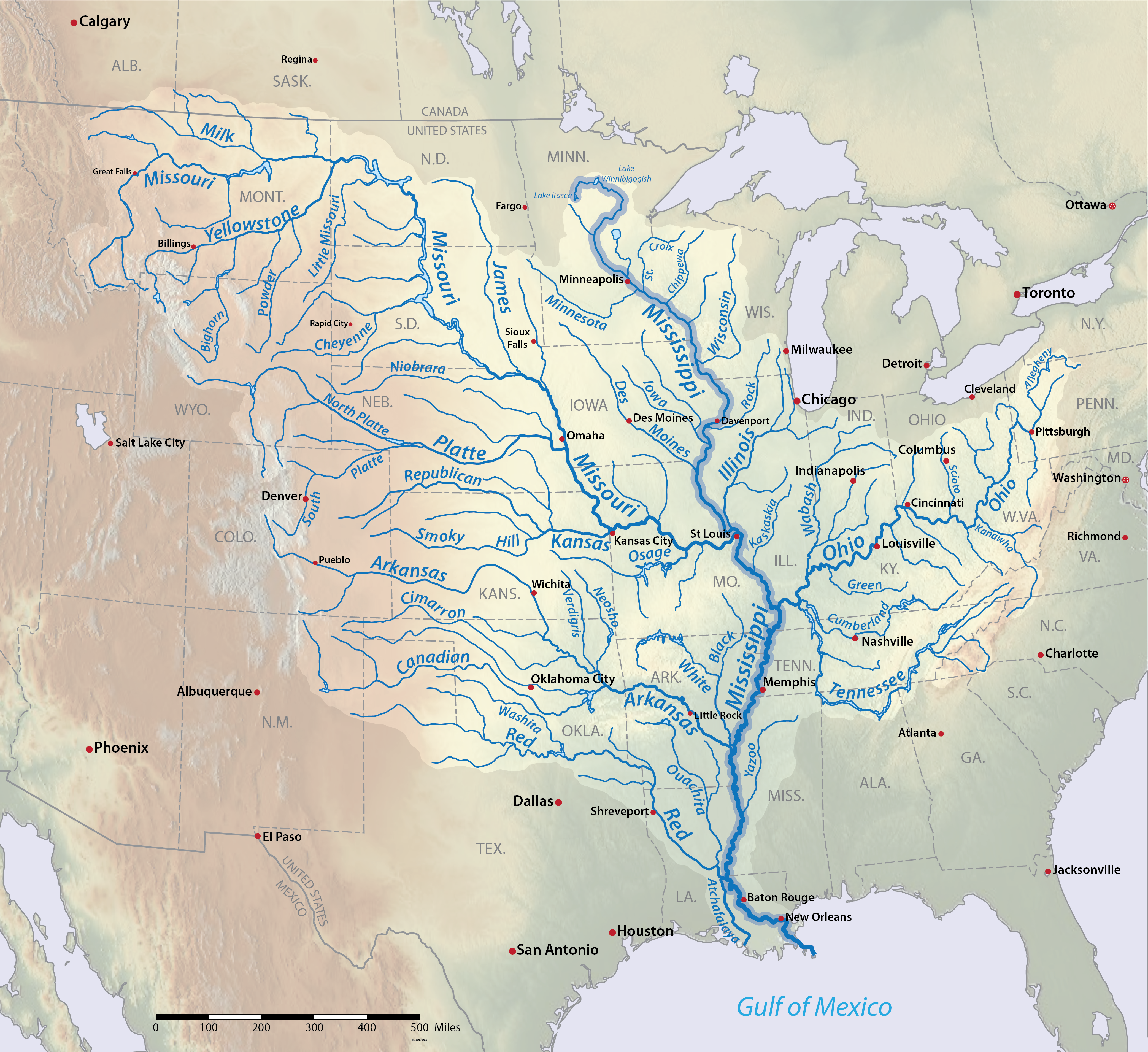

In 1521, the Spanish Empire created the ''Virreinato de Nueva España'' (Viceroyalty of New Spain) to govern its conquests in the Caribbean, North America, and later the Pacific Ocean. In 1682, La Salle claimed Louisiana for France. For the Spanish Empire, this was an intrusion into the northeastern frontier of New Spain. In 1691, Spain created the Province of Tejas in an attempt to inhibit French settlement west of the Mississippi River. Fearing the loss of his American territories in the Seven Years' War, King Louis XV of France ceded Louisiana to King Charles III of Spain with the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau in 1762. The Treaty of Paris of 1763 split Louisiana with the portion east of the Mississippi River (except for

In 1521, the Spanish Empire created the ''Virreinato de Nueva España'' (Viceroyalty of New Spain) to govern its conquests in the Caribbean, North America, and later the Pacific Ocean. In 1682, La Salle claimed Louisiana for France. For the Spanish Empire, this was an intrusion into the northeastern frontier of New Spain. In 1691, Spain created the Province of Tejas in an attempt to inhibit French settlement west of the Mississippi River. Fearing the loss of his American territories in the Seven Years' War, King Louis XV of France ceded Louisiana to King Charles III of Spain with the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau in 1762. The Treaty of Paris of 1763 split Louisiana with the portion east of the Mississippi River (except for Île d'Orléans

Île d'Orléans (; ) is an island located in the Saint Lawrence River about east of downtown Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. It was one of the first parts of the province to be colonized by the French, and a large percentage of French Canadians c ...

) becoming a part of British North America and the portion west of the river becoming the District of Louisiana within New Spain. This eliminated the French threat, and the Spanish provinces of Luisiana, Tejas, and Santa Fe de Nuevo México coexisted with only loosely defined borders. In 1800, French First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte forced King Charles IV of Spain to cede Louisiana to France with the secret Third Treaty of San Ildefonso. Spain continued to administer Louisiana until 1802 when Spain publicly transferred the district to France. The following year, Napoleon sold the territory to the United States to raise money for his military campaigns.Marshall (1914), p. 7.

The United States and the Spanish Empire disagreed over the territorial boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

of 1803. The United States maintained the claim of France that Louisiana included the Mississippi River and "all lands whose waters flow to it". To the west of New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

, the United States assumed the French claim to all land east and north of either the Sabine RiverMarshall (1914), p. 10. or the Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( or ) in the United States or the Río Bravo (del Norte) in Mexico (), also known as Tó Ba'áadi in Navajo language, Navajo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the Southwestern United States a ...

.Marshall (1914), p. 13. "The idea that the Louisiana Purchase extended to the Rio Grande became a certainty with Jefferson early in 1804."At the time of the treaty negotiations, the exploration of the western Mississippi River Basin had only begun. A modern definition of the border initially claimed by the United States begins at the mouth of Sabine Pass on the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

(), thence up the Sabine River to its source (), thence due north (a distance of about along meridian 96° 12 58W) to the southern extent of the Red River drainage basin (), thence westward along the southern extent of the Red River drainage basin to the tripoint

A triple border, tripoint, trijunction, triple point, or tri-border area is a geography, geographical point at which the boundaries of three countries or Administrative division, subnational entities meet. There are 175 international tripoints ...

of the Red River, Arkansas River, and Brazos River drainage basin

A drainage basin is an area of land in which all flowing surface water converges to a single point, such as a river mouth, or flows into another body of water, such as a lake or ocean. A basin is separated from adjacent basins by a perimeter, ...

s (), thence northwestward along the southern extent of the Arkansas River drainage basin to the tripoint of the Mississippi River, Colorado River

The Colorado River () is one of the principal rivers (along with the Rio Grande) in the Southwestern United States and in northern Mexico. The river, the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), 5th longest in the United St ...

, and San Luis drainage basins (), thence northward along the Continental Divide of the Americas to the tripoint of the Mississippi River, Colorado River, and Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook language, Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin language, Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river headwater ...

drainage basins (on Three Waters Mountain) (). At this tripoint, the United States claim to the Oregon Country began (see #Oregon Country.) Spain maintained that all land west of the Calcasieu River

The Calcasieu River ( ; ) is a river on the Gulf Coast of the United States, Gulf Coast in southwestern Louisiana. Approximately long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed J ...

and south of the Arkansas River belonged to Tejas and Santa Fe de Nuevo México.

Oregon Country

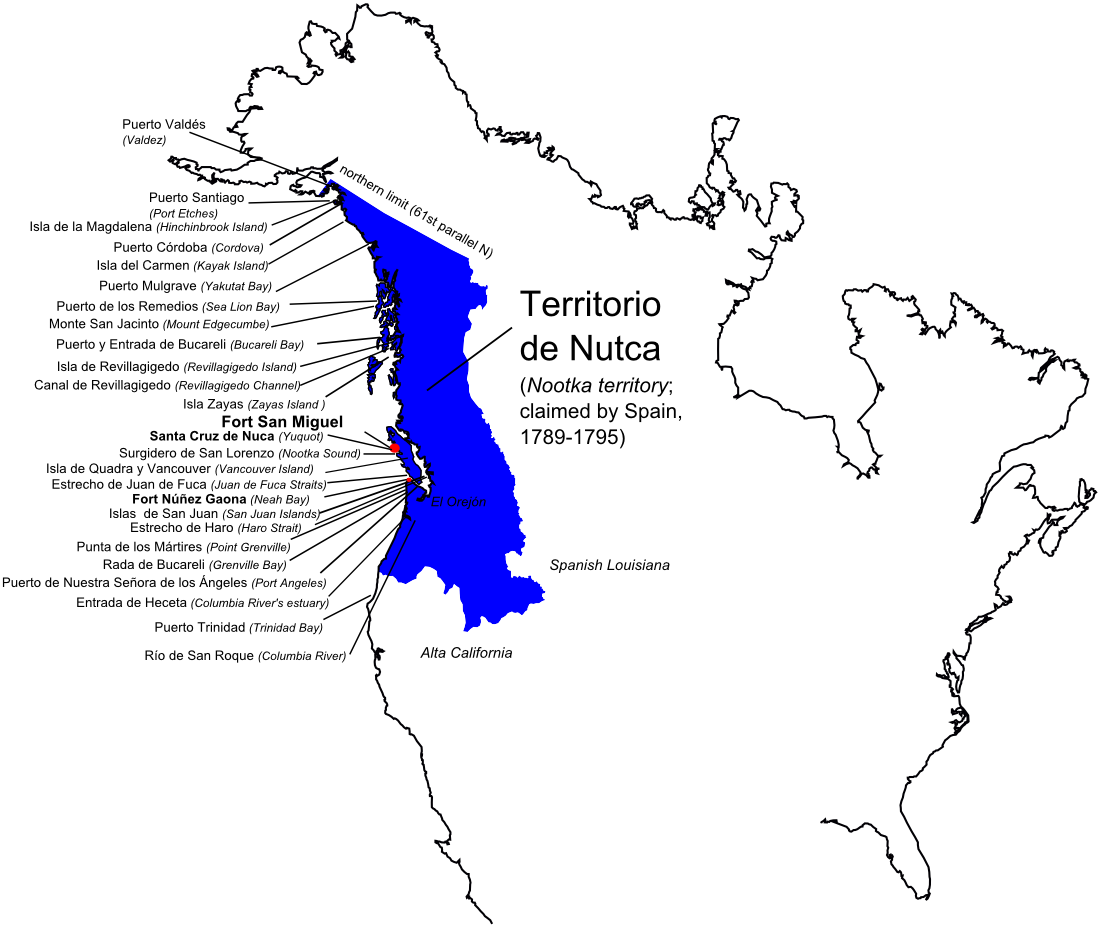

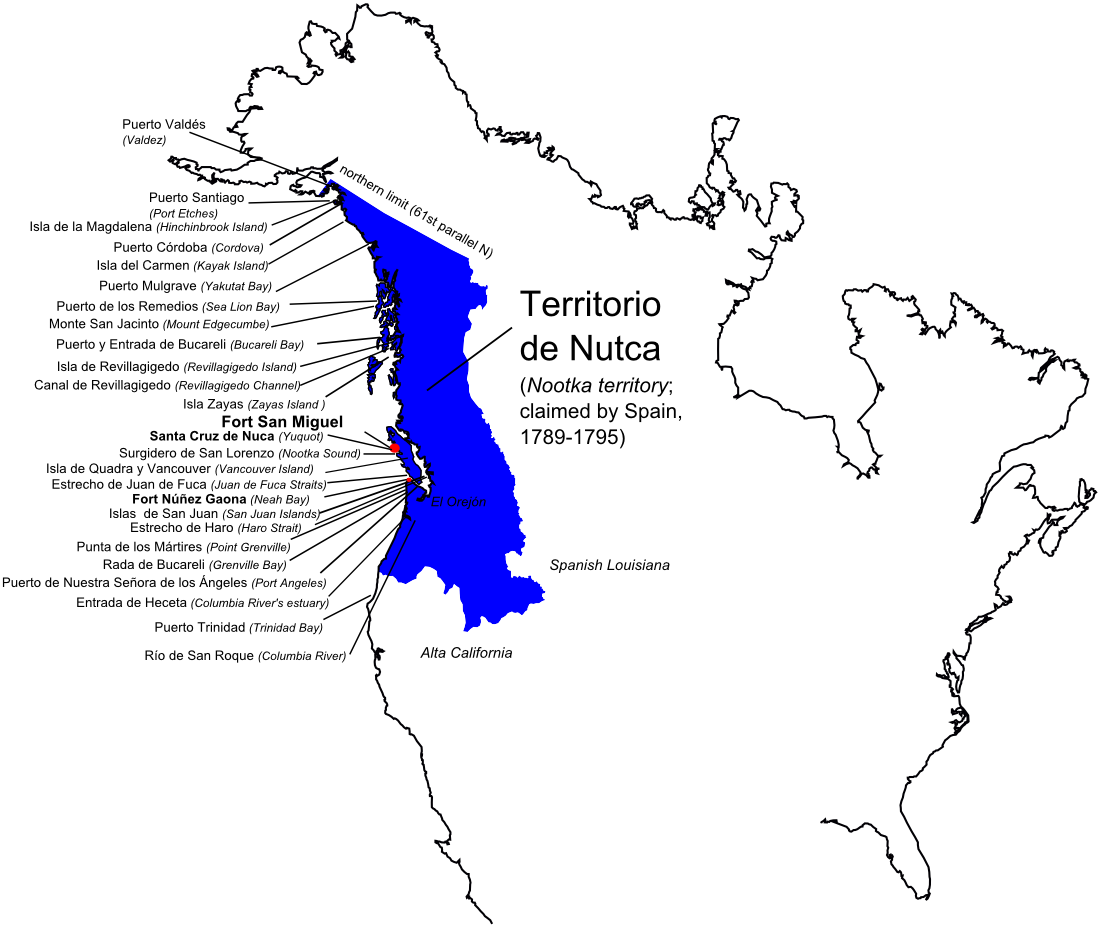

The British government claimed the region west of the Continental Divide between the undefined borders of

The British government claimed the region west of the Continental Divide between the undefined borders of Alta California

Alta California (, ), also known as Nueva California () among other names, was a province of New Spain formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but was made a separat ...

and Russian Alaska on the basis of (1) the third voyage of James Cook in 1778, (2) the Vancouver Expedition in 1791–1795, (3) the solo journey of Alexander Mackenzie to the North Bentinck Arm in 1792–1793, and (4) the exploration of David Thompson in 1807–1812. The Third Nootka Convention of 1794 stipulated that both the British and Spanish would abandon any settlements they had in the Nootka Sound.Carlos Calvo, ''Recueil complet des traités, conventions, capitulations, armistices et autres actes diplomatiques de tous les états de l'Amérique latine,'' Tome IIIe, Paris, Durand, 1862, pp. 366–368/ref> The United States claimed essentially the same region on the basis of (1) Robert Gray's Columbia River expedition, the voyage of Robert Gray up the

Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook language, Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin language, Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river headwater ...

in 1792, (2) the United States Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804–1806, and (3) the establishment of Fort Astoria on the Columbia River in 1811. On 20 October 1818, the Anglo-American Convention of 1818 was signed setting the border between British North America and the United States east of the Continental Divide along the 49th parallel north

The 49th parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 49degree (angle), ° true north, north of Earth's equator. It crosses Europe, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, North America, and the Atlantic Ocean.

The city of Paris is about south of the 49t ...

and calling for joint Anglo-American occupancy west of the Great Divide. The Anglo-American Convention ignored the Nootka Convention of 1794 which gave Spain joint rights in the region. The convention also ignored Russian settlements in the region. The U.S. government referred to this region as the Oregon Country, while the British government referred to the region as the Columbia District

The Columbia District was a fur-trading district in the Pacific Northwest region of North America, in both the United States and British North America in the 19th century. Much of its territory overlapped with the temporarily jointly occupi ...

.

Russian America

On 16 July 1741, the crew of the Imperial Russian Navy ship ''

On 16 July 1741, the crew of the Imperial Russian Navy ship ''Saint Peter

Saint Peter (born Shimon Bar Yonah; 1 BC – AD 64/68), also known as Peter the Apostle, Simon Peter, Simeon, Simon, or Cephas, was one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus and one of the first leaders of the Jewish Christian#Jerusalem ekklēsia, e ...

'' (''Святой Пётр''), captained by Vitus Bering

Vitus Jonassen Bering ( , , ; baptised 5 August 1681 – 19 December 1741),All dates are here given in the Julian calendar, which was in use throughout Russia at the time. also known as Ivan Ivanovich Bering (), was a Danish-born Russia ...

, sighted Mount Saint Elias, the fourth-highest summit in North America. While dispatched on the Russian Great Northern Expedition, they became the first Europeans to land in northwestern North America. The Russian fur trade soon followed the discovery. By 1812, the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

claimed Alaska and the Pacific Coast of North America as far south as the Russian settlement of Fortress Ross, only northwest of the Spain's Presidio Real de San Francisco.

New Spain

The Spanish Empire claimed all lands west of the Continental Divide throughout the Americas.The claim of Spain to all lands west of the Continental Divide in the Americas dated to the

The Spanish Empire claimed all lands west of the Continental Divide throughout the Americas.The claim of Spain to all lands west of the Continental Divide in the Americas dated to the papal bull

A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by the pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the leaden Seal (emblem), seal (''bulla (seal), bulla'') traditionally appended to authenticate it.

History

Papal ...

'' Inter caetera'' issued by Pope Alexander VI on May 4, 1493, which granted to the Crowns of Castile and Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and ; ) is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces of Spain, ...

the rights to colonize all "pagan lands" 100 leagues west of the Azores

The Azores ( , , ; , ), officially the Autonomous Region of the Azores (), is one of the two autonomous regions of Portugal (along with Madeira). It is an archipelago composed of nine volcanic islands in the Macaronesia region of the North Atl ...

and south of the Cabo Verde islands. This edict was superseded by the Treaty of Tordesillas signed on June 7, 1494, which divided the Earth into hemispheres along a meridian 370 leagues west of the Cabo Verde islands. In 1513, explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa claimed the entire "Mar de Sur" (Pacific Ocean) and all lands adjacent for the Crowns of Castile and Aragon. Between 1774 and 1779, King Charles III of Spain ordered three naval expeditions north along the Pacific Coast to assert Spain's territorial claims. In July 1774, Juan José Pérez Hernández reached latitude 54°40′ north off the northwestern tip of Langara Island before being forced to turn south. On 15 August 1775, Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra reached the latitude 59°0′ before returning south. On 23 July 1779, Ignacio de Arteaga y Bazán and Bodega y Quadra reached Puerto de Santiago on Isla de la Magdalena (now Port Etches on Hinchinbrook Island) where they held a formal possession ceremony commemorating Saint James, the patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, Eastern Orthodoxy or Oriental Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, fa ...

of Spain. This marked the northernmost Spanish exploration in the Pacific Ocean.

Between 1788 and 1793, Spain launched several more expeditions north of Alta California. On 24 June 1789, Esteban José Martínez Fernández y Martínez de la Sierra

Esteban José Martínez Fernández y Martínez de la Sierra (1742 – 1798) was a Spanish Navy officer, navigator and explorer from Seville. He was a key figure in Spanish expeditions to the Pacific Northwest and the Nootka Crisis.

Training

...

established the Spanish colony of Santa Cruz de Nuca on the northwest coast of Vancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are of land. The island is the largest ...

. Asserting Spain's claim of exclusive sovereignty and navigation rights, Martínez seized several ships in Nootka Sound provoking the Nootka Crisis

The Nootka Crisis, also known as the Spanish Armament, was an international incident and political dispute between Spain and Great Britain triggered by a series of events revolving around sovereignty claims and rights of navigation and trade. It ...

with Great Britain. In negotiations to resolve the crisis, Spain claimed that its Nootka Territory extended north from Alta California to the 61st parallel north and from the Continental Divide west to the 147th meridian west. On 11 January 1794, the Spanish and British governments signed the Third Nootka Convention which called for the abandonment of all permanent settlements on Nootka Sound. Santa Cruz de Nuca was formally abandoned on 28 March 1795. The convention also stipulated that both nations were free to use Nootka Sound as a port and erect temporary structures, but, "neither ... shall form any permanent establishment in the said port or claim any right of sovereignty or territorial dominion there to the exclusion of the other. And Their said Majesties will mutually aid each other to maintain for their subjects free access to the port of Nootka against any other nation which may attempt to establish there any sovereignty or dominion". On 19 August 1796, Spain made the decision to join the French Republic

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

in their war against Great Britain with the signing of the Second Treaty of San Ildefonso, thus ending Spanish and British cooperation in the Americas.

East of the Continental Divide, the Spanish Empire claimed all land south of the Arkansas River that was west of the Calcasieu River

The Calcasieu River ( ; ) is a river on the Gulf Coast of the United States, Gulf Coast in southwestern Louisiana. Approximately long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed J ...

.At the time of the treaty negotiations, the course of the Calcasieu, Red and Arkansas Rivers were only partially known and the location of the Continental Divide was yet to be determined. A modern definition of the border initially claimed by Spain begins at the mouth of Calcasieu Pass on the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

(), thence up the Calcasieu River to its source (), thence due north (along meridian 93° 12 47W) to the Red River (), thence up the Red River to the meridian (99°15′19″W) of the source of the Medina River (), thence due north along that meridian (99°15′19″W) to the Arkansas River (), thence up the Arkansas River to its source (), thence due west (a distance of about along the parallel 39° 15 30N) to the Continental Divide (), thence northward along the Continental Divide presumably all the way to the Bering Strait. The vast disputed region between the territorial claims of the United States and Spain was occupied primarily by native peoples with very few traders of either Spain or the United States present. In the south, the disputed region between the Calcasieu River and the Sabine River encompassed Los Adaes, the first capital of Spanish Texas. The region between the Calcasieu and Sabine rivers became a lawless no man's land. The United States saw great potential in these western lands, and hoped to settle their borders. Spain, seeing the end of New Spain, hoped to employ its territorial claims before it would be forced to grant Mexico its independence

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state, in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the status of ...

(later in 1821). Spain hoped to regain much of its territory after the regional demands for independence subsided.

Details of the treaty

The treaty, consisting of 16 articles was signed in Adams' State Department office at Washington, on February 22, 1819, by

The treaty, consisting of 16 articles was signed in Adams' State Department office at Washington, on February 22, 1819, by John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

, U.S. Secretary of State, and Luis de Onís, Spanish minister. Ratification was postponed for two years, because Spain wanted to use the treaty as an incentive to keep the United States from giving diplomatic support to the revolutionaries in South America. On February 24, the U.S. Senate ratified the treaty unanimously,Marshall (1914), p. 63. but because of Spain's stalling, a new ratification was necessary and this time there were objections. Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

and other Western spokesmen demanded that Spain also give up Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

. This proposal was defeated by the Senate, which ratified the treaty a second time on February 19, 1821, following ratification by Spain on October 24, 1820. Ratifications were exchanged three days later and the treaty was proclaimed on February 22, 1821, two years after the signing.

The Treaty closed the first era of United States expansion by providing for the cession of East Florida under Article 2; the abandonment of the controversy over West Florida under Article 2 (a portion of which had been seized by the United States); and the definition of a boundary with New Spain, that clearly made Texas a part of it, under Article 3, thus ending much of the vagueness in the boundary of the Louisiana Purchase. Spain also ceded to the U.S. its claims to the Oregon Country, under Article 3.

The U.S. did not pay Spain for Florida, but instead agreed to pay the legal claims of American citizens against Spain, to a maximum of $5 million, under Article 11.The U.S. commission established to adjudicate claims considered some 1,800 claims and agreed that they were collectively worth $5,454,545.13. Since the treaty limited the payment of claims to $5 million, the commission reduced the amount paid out proportionately by percent. Under Article 12, Pinckney's Treaty of 1795 between the U.S. and Spain was to remain in force. Under Article 15, Spanish goods received exclusive most-favored-nation privileges in the ports at Pensacola and St. Augustine for twelve years.

Under Article 2, the U.S. received ownership of Spanish Florida. Under Article 3, the U.S. relinquished its own claims on parts of Texas west of the Sabine River and other Spanish areas.

Border

Article 3 of the treaty states:The Boundary Line between the two Countries, West of the Mississippi, shall begin on theAt the time the treaty was signed, the course of the Sabine River, Red River, and Arkansas River had only been partially charted. Furthermore, the rivers changed course periodically. It would take many years before the location of the border would be fully determined. South of the 32nd parallel north, the Spanish Empire and the United States settled for the U.S. claim along the Sabine River. Between the meridians 94°2′45" and 100° west, the parties settled on the Spanish claim along the Red River. West of the 100th meridian west, the parties settled on the Spanish claim along the Arkansas River. From the source of the Arkansas River in theGulf of Mexico The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ..., at themouth A mouth also referred to as the oral is the body orifice through which many animals ingest food and animal communication#Auditory, vocalize. The body cavity immediately behind the mouth opening, known as the oral cavity (or in Latin), is also t ...of the River Sabine in the Sea (), continuing North, along the Western Bank of that River, to the 32d degree of Latitude (); thence by a Line due North to the degree of Latitude, where it strikes the Rio Roxo of Nachitoches, or Red-River (), then following the course of the Rio-Roxo Westward to the degree of Longitude, 100 West from London and 23 from Washington (), then crossing the said Red-River, and running thence by a Line due North to the River Arkansas (), thence, following the Course of the Southern bank of the Arkansas to its source in Latitude, 42. North and thence by that parallel of Latitude to the South-Sea acific Ocean The whole being as laid down in Melishe's Map of the United States, published at Philadelphia, improved to the first of January 1818. But if the Source of the Arkansas River shall be found to fall North or South of Latitude 42, then the Line shall run from the said Source () due South or North, as the case may be, till it meets the said Parallel of Latitude 42 (), and thence along the said Parallel to the South Sea ().

Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in great-circle distance, straight-line distance from the northernmost part of Western Can ...

, the parties settled on a border due north along that meridian (106°20′37″W) to the 42nd parallel north

The 42nd parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 42 degree (angle), degrees true north, north of the Earth, Earth's equator, equatorial plane. It crosses Europe, the Mediterranean Sea, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, North America, and the Atla ...

, thence west along the 42nd parallel to the Pacific Ocean.

Spain won substantial buffer zones around its provinces of Tejas, Santa Fe de Nuevo México, and Alta California in New Spain. While the United States relinquished substantial territory east of Continental Divide, the newly defined border allowed settlement of the southwestern part of the State of Louisiana, the Arkansas Territory

The Arkansas Territory was a organized incorporated territory of the United States, territory of the United States from July 4, 1819, to June 15, 1836, when the final extent of Arkansas Territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the ...

, and the Missouri Territory.

Spain relinquished all claims in the Americas north of the 42nd parallel north. This was a historic retreat in its 327-year pursuit of lands in the Americas. The previous Anglo-American Convention of 1818 meant that both American and British citizens could settle land north of the 42nd parallel and west of the Continental Divide. The United States now had a firm foothold on the Pacific Coast and could commence settlement of the jointly occupied Oregon Country (known as the Columbia District

The Columbia District was a fur-trading district in the Pacific Northwest region of North America, in both the United States and British North America in the 19th century. Much of its territory overlapped with the temporarily jointly occupi ...

to the British government). The Russian Empire also claimed this entire region as part of Russian America.

For the United States, this Treaty (and the Treaty of 1818 with Britain agreeing to joint control of the Pacific Northwest) meant that its claimed territory now extended far west from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. For Spain, it meant that it kept its colony of Texas and also kept a buffer zone between its colonies in California and New Mexico and the U.S. territories. Many historians consider the Treaty to be a great achievement for the U.S., as time validated Adams's vision that it would allow the U.S. to open trade with the Orient across the Pacific.

Informally this new border has been called the "Step Boundary", although the step-like shape of the boundary was not apparent for several decades—the source of the Arkansas, believed to be near the 42nd parallel north, was not known until John C. Frémont located it in the 1840s, hundreds of miles south of the 42nd parallel.

Implementation

Washington set up a commission, 1821 to 1824, that handled American claims against Spain. Many notable lawyers, including Daniel Webster and William Wirt, represented claimants before the commission. Dr. Tobias Watkins served as secretary. During its term, the commission examined 1,859 claims arising from over 720 spoliation incidents, and distributed the $5 million in a basically fair manner. The treaty reduced tensions with Spain (and after 1821 Mexico), and allowed budget cutters in Congress to reduce the army budget and reject the plans to modernize and expand the army proposed by Secretary of War John C. Calhoun. The treaty was honored by both sides, although inaccurate maps from the treaty meant that the boundary between Texas and Oklahoma remained unclear for most of the 19th century.Later developments

Mexican War of Independence

The Mexican War of Independence (, 16 September 1810 – 27 September 1821) was an armed conflict and political process resulting in Mexico's independence from the Spanish Empire. It was not a single, coherent event, but local and regional ...

). Luis de Onís published a 152-page memoir on the diplomatic negotiation in 1820, which was translated from Spanish to English by US diplomatic commission secretary, Tobias Watkins in 1821.

Spain finally recognized the independence of Mexico with the Treaty of Córdoba signed on August 24, 1821. While Mexico was not initially a party to the Adams–Onís Treaty, in 1831 Mexico ratified the treaty by agreeing to the 1828 Treaty of Limits with the U.S.

With the Russo-American Treaty of 1824, the Russian Empire ceded its claims south of parallel 54°40′ north to the United States. With the Treaty of Saint Petersburg in 1825, Russia set the southern border of Alaska on the same parallel in exchange for the Russian right to trade south of that border and the British right to navigate north of that border. This set the absolute limits of the Oregon Country/Columbia District between the 42nd parallel north and the parallel 54°40′ north west of the Continental Divide.

By the mid-1830s, a controversy developed regarding the border with Texas, during which the United States demonstrated that the Sabine and Neches rivers had been switched on maps, moving the frontier in favor of Mexico. As a consequence, the eastern boundary of Texas was not firmly established until the independence of the Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas (), or simply Texas, was a country in North America that existed for close to 10 years, from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846. Texas shared borders with Centralist Republic of Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande, an ...

in 1836. It was not agreed upon by the United States and Mexico until the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, which concluded the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

. That treaty also formalized the cession by Mexico of Alta California and today's American Southwest, except for the territory of the later Gadsden Purchase of 1854.

Another dispute occurred after Texas joined the Union. The treaty stated that the boundary between the French claims on the north and the Spanish claims on the south was Rio Roxo de Natchitoches (Red River) until it reached the 100th meridian, as noted on the John Melish map of 1818. But, the 100th meridian on the Melish map was marked some east of the true 100th meridian, and the Red River forked about east of the 100th meridian. Texas claimed the land south of the North Fork, and the United States claimed the land north of the South Fork (later called the

Another dispute occurred after Texas joined the Union. The treaty stated that the boundary between the French claims on the north and the Spanish claims on the south was Rio Roxo de Natchitoches (Red River) until it reached the 100th meridian, as noted on the John Melish map of 1818. But, the 100th meridian on the Melish map was marked some east of the true 100th meridian, and the Red River forked about east of the 100th meridian. Texas claimed the land south of the North Fork, and the United States claimed the land north of the South Fork (later called the Prairie Dog Town Fork Red River

Prairie Dog Town Fork Red River () is a sandy-braided stream about long, formed at the confluence of Palo Duro Creek and Tierra Blanca Creek, about northeast of Canyon, Texas, Canyon in Randall County, Texas, and flowing east-southeastward to th ...

). In 1860, Texas organized the area as Greer County. The matter was not settled until a United States Supreme Court ruling in 1896 upheld federal claims to the territory, after which it was added to the Oklahoma Territory.

The treaty gave rise to a later border dispute between the states of Oregon and California, which remains unresolved. Upon statehood in 1850, California established the 42nd parallel as its constitutional de jure border as it had existed since 1819 when the territory was part of Spanish Mexico. In an 1868–1870 border survey following the admission of Oregon as a state, errors were made in demarcating and marking the Oregon-California border, creating a dispute that continues to this day.

In 2020, a hoax appeared in Spain according to which, in 2055, the Adams–Onís Treaty would expire and Florida would be returned to Spain by the United States, which is false.

See also

* List of treaties * Spain–United States relations * Spanish expeditions to the Pacific Northwest * Stephen H. Long's Expedition of 1820, an outcome of the treaty * Republic of East FloridaFootnotes

References

Bibliography

* * * , the standard history. * * Warren, Harris G. "Textbook Writers and the Florida" Purchase" Myth." ''Florida Historical Quarterly'' 41.4 (1963): 325–33online

* . ;Sources

Avalon Project – Treaty Text

External links

Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture – Adams–Onís Treaty

{{DEFAULTSORT:Adams-Onis Treaty 1819 treaties Boundary treaties New Spain Missouri Territory Spanish Florida Spanish Texas Treaties of the Spanish Empire Treaties of the United States Mexico–United States border 1819 in New Spain 1819 in the United States 1819 in Nueva California 16th United States Congress History of United States expansionism Pre-statehood history of Florida Spain–United States relations Red River of the South February 1819 Purchased territories Eponymous treaties Sabine River (Texas–Louisiana)