Adah Isaacs Menken on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Adah Isaacs Menken (June 15, 1835August 10, 1868) was an American actress, painter and poet

"Adah Isaacs Menken"

''Handbook of Texas Online,'' published by the Texas State Historical Association, accessed August 10, 2012. She was best known for her performance in the

After Cuba, Menken left dance for acting, and began working as an actress in Texas first. According to Gregory Eiselein, she gave

After Cuba, Menken left dance for acting, and began working as an actress in Texas first. According to Gregory Eiselein, she gave

Jewish Virtual Library, 2012, accessed August 8, 2012. She also began to be published in the '' Jewish Messenger'' of New York. Ada added an "h" to her first name and an "s" to Isaac, and by 1858 she billed herself as Adah Isaacs Menken. She eventually worked as an actress in New York and San Francisco, as well as in touring productions across the country. She also became known for her poetry and painting. While none of her art was well received by major critics, she became a celebrity. At this time, Menken wore her wavy hair short, a highly unusual style for women of the time. She cultivated a

"Adah Isaacs Menken"

, KPO/KNBC radio script later collected in ''San Francisco Is Your Home,'' Stanford University Press, 1947; reprinted at Virtual Museum of San Francisco website, accessed August 8, 2012. While in New York, Menken met the poet

''Performing Menken: Adah Isaacs Menken and the Birth of American Celebrity''

(2003), ().Kleitz, Dorsey

"Adah Isaacs Menken"

in ''Encyclopedia of American Poetry: The Nineteenth Century'', ed. Eri L. Haralson, pp. 294–296 (1998) ().Alcaro, Marion Walker

''Walt Whitman's Mrs. G: A Biography of Anne Gilchrist''

pp. 129–30 (1991) (). She identified with the controversial poet, and declared her bohemian identity through her support for him. That year, Menken also wrote an article on the 1860 election, an unusual topic for a woman, which further added to her image. When Menken met

After it ended, she appealed to her business manager Jimmie Murdock to help her become recognized as a great actress. Murdock dissuaded Menken from that goal, as he knew she had little acting talent. He offered her the "

After it ended, she appealed to her business manager Jimmie Murdock to help her become recognized as a great actress. Murdock dissuaded Menken from that goal, as he knew she had little acting talent. He offered her the " Menken arranged to play in a production of ''Mazeppa'' in London and France for much of 1864 to 1866. Controversy arose over her costume, and she responded to critics in the newspapers of London by saying that she was influenced by classical sculpture, and that her costume was more modest than those of ballet or

Menken arranged to play in a production of ''Mazeppa'' in London and France for much of 1864 to 1866. Controversy arose over her costume, and she responded to critics in the newspapers of London by saying that she was influenced by classical sculpture, and that her costume was more modest than those of ballet or

''Victorian Sensation, Or, the Spectacular, the Shocking, and the Scandalous in Nineteenth-Century Britain''

Anthem Press, 2003, p. 270. She was so well known that she was referred to as "the Menken," needing no other name. Jokes and poems were printed about the controversy, and ''

Playing in a sold-out run of ''Les pirates de la savane'' in Paris in 1866, Menken had an affair with the French novelist

Playing in a sold-out run of ''Les pirates de la savane'' in Paris in 1866, Menken had an affair with the French novelist

"Adah Isaacs Menken (Bertha Theodore) (1835–1868)"

''The Vault at Pfaff's'', hosted at Lehigh University, includes several photos *

"La Belle Menken"

''National Magazine'', 1905, at Open Archive, includes several photos

Jewish Virtual Library, 2012 * 21 photos, including one with

"Adah Isaacs Menken"

''Handbook of Texas Online,'' published by the Texas State Historical Association, accessed August 10, 2012. She was best known for her performance in the

hippodrama

Hippodrama, horse drama, or equestrian drama is a genre of theatrical show blending circus horsemanship display with popular melodrama theatre.

Definition

Kimberly Poppiti defines hippodrama as "plays written or performed to include a live horse ...

'' Mazeppa'', with a climax that featured her apparently nude and riding a horse on stage. After great success for a few years with the play in New York and San Francisco, she appeared in a production in London and Paris, from 1864 to 1866. After a brief trip back to the United States, she returned to Europe. She became ill within two years and died in Paris at the age of 33.

Menken told many versions of her origins, including her name, place of birth, ancestry, and religion, and historians have differed in their accounts. Most have said she was born a Louisiana Creole

Louisiana Creole ( lou, Kréyòl Lalwizyàn, links=no) is a French-based creole language spoken by fewer than 10,000 people, mostly in the state of Louisiana. It is spoken today by people who may racially identify as White, Black, mixed, and N ...

Catholic, with European and African ancestry. A celebrity who created sensational performances in the United States and Europe, she married several times and was also known for her affairs. She had two sons, both of whom died in infancy.

Though she was better known as an actress, Menken sought to be known as a writer. She published about 20 essays, 100 poems, and a book of her collected poems, from 1855 to 1868 (the book was published posthumously). Early work was devoted to family and after her marriage, her poetry and essays featured Jewish themes. Beginning with work published after moving to New York, with which she changed her style, Menken expressed a wide range of emotions and ideas about women's place in the world. Her collection ''Infelicia'' went through several editions and was in print until 1902.

Early life and education

Accounts of Menken's early life and origins vary considerably. In her autobiographical "Some Notes of Her Life in Her Own Hand," published in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' in 1868, Menken said she was born in Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectur ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and lived in Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

as a child before her family settled in New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

. There are many conflicting reports as to Menken's birth name, but she has been called Marie Rachel Adelaide de Vere Spenser and Adah Bertha Theodore, and Ed James, a journalist friend, wrote after her death: "Her real name was Adelaide McCord, and she was born at Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Milneburg

Milneburg was a town on the southern shore of Lake Pontchartrain in Louisiana that was absorbed into the city of New Orleans. A neighborhood to the south of this area is still sometimes known by this name; the former location of Milneburg is now i ...

, near New Orleans, on June 15, 1835."Barca, Dane. "Adah Isaacs Menken: Race and Transgendered Performance in the Nineteenth Century." ''MELUS'', Volume 29. Number 3–4. (2004): pp. 293–306. . Menken's birth year also varies, with some records stating 1835 and some stating 1832. Elsewhere, in 1865, she wrote that her birth name was Dolores Adios Los Fiertes, and that she was the daughter of a French woman from New Orleans and a Spanish-Jewish man. About 1940, the consensus of scholars was that her parents were Auguste Théodore, a free Black man, and Marie, a mixed-race

Mixed race people are people of more than one race or ethnicity. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mixed race people in a variety of contexts, including ''multiethnic'', ''polyethnic'', occasionally ''bi-ethn ...

Creole, and Adah was raised as a Catholic. She had a sister and a brother.

Based on Menken's assertions of being a native of New Orleans, Wolf Mankowitz

Cyril Wolf Mankowitz (7 November 1924 – 20 May 1998) was an English writer, playwright and screenwriter. He is particularly known for three novels— ''Make Me an Offer'' (1952), '' A Kid for Two Farthings'' (1953) and ''My Old Man's a Dustma ...

and others have studied Board of Health records for the city. They have concluded that Ada was born in the city as the legitimate daughter of Auguste Théodore, a free man of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Na ...

(mixed race) and his wife Magdaleine Jean Louis Janneaux, likely also a Louisiana Creole

Louisiana Creole ( lou, Kréyòl Lalwizyàn, links=no) is a French-based creole language spoken by fewer than 10,000 people, mostly in the state of Louisiana. It is spoken today by people who may racially identify as White, Black, mixed, and N ...

. Ada would have been raised as Catholic. However, in 1990, John Cofran, using census records, said that she was born as Ada C. McCord, in Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the seat of Shelby County in the southwest part of the state; it is situated along the Mississippi River. With a population of 633,104 at the 2020 U.S. census, Memphis is the second-mos ...

, in late 1830. He said she was the daughter of an Irish merchant, Richard McCord, and his wife Catherine.Brooks, Daphne A. "Lady Menken's Secret: Adah Isaacs Menken, Actress Biographies and the Race for Sensation." ''Legacy'', Volume 15. Number 1. (1998): pp. 68–77. According to Cofran, her father died when she was young and her mother remarried. The family then moved from Memphis to New Orleans.

Ada was said to have been a bright student; she became fluent in French and Spanish, and was described as having a gift for languages. As a child, Adah performed as a dancer in the ballet of the French Opera House

The French Opera House, or ''Théâtre de l'Opéra'', was an opera house in New Orleans. It was one of the city's landmarks from its opening in 1859 until it was destroyed by fire in 1919. It stood in the French Quarter at the uptown lake corner o ...

in New Orleans. In her later childhood, she performed as a dancer in Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

, Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, where she was crowned "Queen of the Plaza."

American career

After Cuba, Menken left dance for acting, and began working as an actress in Texas first. According to Gregory Eiselein, she gave

After Cuba, Menken left dance for acting, and began working as an actress in Texas first. According to Gregory Eiselein, she gave Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

readings, and wrote poems and sketches for ''The Liberty Gazette.'' She was married for the first time in Galveston County

Galveston County ( ) is a county in the U.S. state of Texas, located along the Gulf Coast adjacent to Galveston Bay. As of the 2020 census, the population was 350,682. The county was founded in 1838. The county seat is the City of Galveston, ...

, in February 1855, to G. W. Kneass, a musician. The marriage had ended by sometime in 1856, when she met and in 1856 married the man more generally considered her first husband, Alexander Isaac Menken, a musician who was from a prominent Reform Jewish

Reform Judaism, also known as Liberal Judaism or Progressive Judaism, is a major Jewish denomination that emphasizes the evolving nature of Judaism, the superiority of its ethical aspects to its ceremonial ones, and belief in a continuous searc ...

family in Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

.

He began to act as her manager, and Ada Menken performed as an actress in the Midwest and Upper South, also giving literary readings. She received decent reviews, which noted her "reckless energy," and performed with men who became notable actors: Edwin Booth

Edwin Thomas Booth (November 13, 1833 – June 7, 1893) was an American actor who toured throughout the United States and the major capitals of Europe, performing Shakespearean plays. In 1869, he founded Booth's Theatre in New York. Some theatri ...

in Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border ...

and James E. Murdoch in Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the List of muni ...

.

In 1857, the couple moved to Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

, where Menken created her Jewish roots, telling a reporter that she was born Jewish. She did study Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in the ...

and stayed with the faith, although she never formally converted. In this period, she published poetry and articles on Judaism in ''The Israelite

''The American Israelite'' is an English-language Jewish newspaper published weekly in Cincinnati, Ohio. Founded in 1854 as ''The Israelite'' and assuming its present name in 1874, it is the longest-running English-language Jewish newspaper stil ...

'' in Cincinnati. The newspaper was founded by Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise

Isaac Mayer Wise (29 March 1819, Lomnička – 26 March 1900, Cincinnati) was an American Reform rabbi, editor, and author. At his death he was called "the foremost rabbi in America".

Early life

Wise was born on 29 March 1819 in Steingrub in B ...

, who was crucial to the Reform Judaism movement in the United States."Adah Isaacs Menken"Jewish Virtual Library, 2012, accessed August 8, 2012. She also began to be published in the '' Jewish Messenger'' of New York. Ada added an "h" to her first name and an "s" to Isaac, and by 1858 she billed herself as Adah Isaacs Menken. She eventually worked as an actress in New York and San Francisco, as well as in touring productions across the country. She also became known for her poetry and painting. While none of her art was well received by major critics, she became a celebrity. At this time, Menken wore her wavy hair short, a highly unusual style for women of the time. She cultivated a

bohemian

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Beer

* National Bohemian, a brand brewed by Pabst

* Bohemian, a brand of beer brewed by Molson Coors

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, origin ...

and at times androgynous

Androgyny is the possession of both masculine and feminine characteristics. Androgyny may be expressed with regard to biological sex, gender identity, or gender expression.

When ''androgyny'' refers to mixed biological sex characteristics i ...

appearance. She deliberately created her image at a time when the growth of popular media helped to publicize it.

In 1859, Menken appeared on Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

in New York City in the play '' The French Spy.'' Her work was not highly regarded by critics. ''The New York Times'' described her as "the worst actress on Broadway." ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the w ...

'' said, "she is delightfully unhampered by the shackles of talent." Menken continued to perform small parts in New York, as well as reading Shakespeare in performance, and giving lectures.

Her third husband was John C. Heenan

John Camel Heenan, also known as the Benicia Boy (2 May 1834 – 28 October 1873) was an American Bare-knuckle boxing, bare-knuckle prize fighter. Though highly regarded, he had only three formal fights in his career, losing two and drawing one. ...

, a popular Irish-American prizefighter

Professional boxing, or prizefighting, is regulated, sanctioned boxing. Professional boxing bouts are fought for a purse that is divided between the boxers as determined by contract. Most professional bouts are supervised by a regulatory autho ...

whom she married in 1859. Some time after their marriage, the press discovered she did not yet have a legal divorce from Menken and accused her of bigamy

In cultures where monogamy is mandated, bigamy is the act of entering into a marriage with one person while still legally married to another. A legal or de facto separation of the couple does not alter their marital status as married persons. I ...

. She had expected Menken to handle the divorce, which he eventually did.

As John Heenan was one of the most famous and popular figures in America, the press also accused Menken of marrying for his celebrity. She billed herself as Mrs. Heenan in Boston, Providence, Baltimore, and Philadelphia, using his name despite their divorce within a year of marriage. They had a son, who died soon after birth.Dickson, Samuel"Adah Isaacs Menken"

, KPO/KNBC radio script later collected in ''San Francisco Is Your Home,'' Stanford University Press, 1947; reprinted at Virtual Museum of San Francisco website, accessed August 8, 2012. While in New York, Menken met the poet

Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among t ...

and some others of his bohemian circle. She was influenced by his work and began to write in a more confessional style while adhering to common sentimental conventions of the time. In 1860–61, she published 25 poems in the ''Sunday Mercury

''Sunday Mercury'' is a Sunday tabloid published in Birmingham, UK, and now owned by Reach plc.

The first edition was published on 29 December 1918. The first editor was John Turner Fearon (1869–1937), who left the Dublin-based ''Freeman's ...

,'' an entertainment newspaper in New York. These were later collected with six more in her only book, '' Infelicia,'' published a few months after her death. By publishing in a newspaper, she reached a larger audience than through women's magazines, including both men and women readers who might go to see her perform as an actress.

In 1860, Menken wrote a review titled "Swimming Against the Current," which praised Whitman's new edition of ''Leaves of Grass

''Leaves of Grass'' is a poetry collection by American poet Walt Whitman. Though it was first published in 1855, Whitman spent most of his professional life writing and rewriting ''Leaves of Grass'', revising it multiple times until his death. Th ...

,'' saying he was "centuries ahead of his contemporaries."Sentilles, Renée M''Performing Menken: Adah Isaacs Menken and the Birth of American Celebrity''

(2003), ().Kleitz, Dorsey

"Adah Isaacs Menken"

in ''Encyclopedia of American Poetry: The Nineteenth Century'', ed. Eri L. Haralson, pp. 294–296 (1998) ().Alcaro, Marion Walker

''Walt Whitman's Mrs. G: A Biography of Anne Gilchrist''

pp. 129–30 (1991) (). She identified with the controversial poet, and declared her bohemian identity through her support for him. That year, Menken also wrote an article on the 1860 election, an unusual topic for a woman, which further added to her image. When Menken met

Charles Blondin

Charles Blondin (born Jean François Gravelet, 28 February 182422 February 1897) was a French tightrope walker and acrobat. He toured the United States and was known for crossing the Niagara Gorge on a tightrope.

During an event in Dublin in ...

, notable for crossing Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls () is a group of three waterfalls at the southern end of Niagara Gorge, spanning the border between the province of Ontario in Canada and the state of New York in the United States. The largest of the three is Horseshoe Falls, ...

on a tightrope, the two were quickly attracted to each other. She suggested she would marry him if they could perform a couple's act above the falls. Blondin refused, saying that he would be "distracted by her beauty." The two had an affair, during which they conducted a vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment born in France at the end of the 19th century. A vaudeville was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a dramatic composition ...

tour across the United States.

''Mazeppa''

After it ended, she appealed to her business manager Jimmie Murdock to help her become recognized as a great actress. Murdock dissuaded Menken from that goal, as he knew she had little acting talent. He offered her the "

After it ended, she appealed to her business manager Jimmie Murdock to help her become recognized as a great actress. Murdock dissuaded Menken from that goal, as he knew she had little acting talent. He offered her the "breeches role

A breeches role (also pants role or trouser role, or Hosenrolle) is one in which an actress appears in male clothing. Breeches, tight-fitting knee-length pants, were the standard male garment at the time these roles were introduced. The theatric ...

" (that of a man) of the noble Tartar

Tartar may refer to:

Places

* Tartar (river), a river in Azerbaijan

* Tartar, Switzerland, a village in the Grisons

* Tərtər, capital of Tartar District, Azerbaijan

* Tartar District, Azerbaijan

* Tartar Island, South Shetland Islands, Ant ...

in the hippodrama

Hippodrama, horse drama, or equestrian drama is a genre of theatrical show blending circus horsemanship display with popular melodrama theatre.

Definition

Kimberly Poppiti defines hippodrama as "plays written or performed to include a live horse ...

'' Mazeppa,'' based on the poem of that title by Lord Byron (and ultimately on the life of Ivan Mazepa

Ivan Stepanovych Mazepa (also spelled Mazeppa; uk, Іван Степанович Мазепа, pl, Jan Mazepa Kołodyński; ) was a Ukrainian military, political, and civic leader who served as the Hetman of Zaporizhian Host in 1687–1708. ...

). At the climax of this hit, the Tartar was stripped of his clothing, tied to his horse, and sent off to his death.Buszek, Maria-Elena. "Representing 'Awarishness': Burlesque, Feminist Transgression and the 19th-Century Pin-Up," ''TDR'', Volume 43. Number 4 (1988): pp. 141–162. The audiences were thrilled with the scene, although the production used a dummy strapped to a horse, which was led away by a handler giving sugar cubes. Menken wanted to perform the stunt herself. Dressed in nude tights and riding a horse on stage, she appeared to be naked and caused a sensation. New York audiences were shocked but still attended and made the play popular.

Menken took the production of ''Mazeppa'' to San Francisco. Audiences again flocked to the show. She became known across the country for this role, and San Francisco adopted her as its performer.

In 1862, she married Robert Henry Newell

Robert Henry Newell (December 13, 1836 – July 1901) was a 19th-century American humorist.

During the U.S. Civil War, Newell wrote a series of satirical articles using the pseudonym Orpheus C. Kerr, commenting on the war and contemporary socie ...

, a humorist and editor of the ''Sunday Mercury

''Sunday Mercury'' is a Sunday tabloid published in Birmingham, UK, and now owned by Reach plc.

The first edition was published on 29 December 1918. The first editor was John Turner Fearon (1869–1937), who left the Dublin-based ''Freeman's ...

'' in New York, who had recently published most of her poetry. They were together about three years. Next she wed James Paul Barkley, a gambler, in 1866, but soon returned without him to France, where she was performing. There she had their son, whom she named Louis Dudevant Victor Emanuel Barkley. The baby's godmother was the author George Sand

Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil (; 1 July 1804 – 8 June 1876), best known by her pen name George Sand (), was a French novelist, memoirist and journalist. One of the most popular writers in Europe in her lifetime, bein ...

(A. F. Lesser). Louis died in infancy.

Menken arranged to play in a production of ''Mazeppa'' in London and France for much of 1864 to 1866. Controversy arose over her costume, and she responded to critics in the newspapers of London by saying that she was influenced by classical sculpture, and that her costume was more modest than those of ballet or

Menken arranged to play in a production of ''Mazeppa'' in London and France for much of 1864 to 1866. Controversy arose over her costume, and she responded to critics in the newspapers of London by saying that she was influenced by classical sculpture, and that her costume was more modest than those of ballet or burlesque

A burlesque is a literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects.

. The show opened on October 3, 1864, at the Astley Theatre to "overflowing houses."Diamond, Michael''Victorian Sensation, Or, the Spectacular, the Shocking, and the Scandalous in Nineteenth-Century Britain''

Anthem Press, 2003, p. 270. She was so well known that she was referred to as "the Menken," needing no other name. Jokes and poems were printed about the controversy, and ''

Punch

Punch commonly refers to:

* Punch (combat), a strike made using the hand closed into a fist

* Punch (drink), a wide assortment of drinks, non-alcoholic or alcoholic, generally containing fruit or fruit juice

Punch may also refer to:

Places

* Pun ...

'' wrote:

Here's half the town - if bills be true -(The last line refers to John Cartlich, equestrian performer ) During this time of her greatest earning, she was generous to friends, theatre people in need, and charities. While in Europe, the Menken continued to play to the American public as well, in terms of her image. As usual, she attracted a crowd of male admirers, including such prominent figures as the writer

To Astley's nightly thronging,

To see the Menken throw aside

All to her sex belonging,

Stripping off woman's modesty,

With woman's outward trappings -

A barebacked jade on barebacked steed,

In Cartlich's old strappings!

Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

, the humorist Tom Hood

Tom Hood (19 January 183520 November 1874) was an English humorist and playwright, and a prolific author. He was the son of the poet and author Thomas Hood. ''Pen and Pencil Pictures'' (1857) was the first of his illustrated books. His most s ...

, and the dramatist and novelist Charles Reade

Charles Reade (8 June 1814 – 11 April 1884) was a British novelist and dramatist, best known for '' The Cloister and the Hearth''.

Life

Charles Reade was born at Ipsden, Oxfordshire, to John Reade and Anne Marie Scott-Waring, and had at leas ...

.Schuele, Donna C. "None Could Deny the Eloquence of the Lady: Women, Law and Government in California, 1850–1890," ''California History'', Volume 81. Number 3-4. (2003): pp. 169–198.

Later life

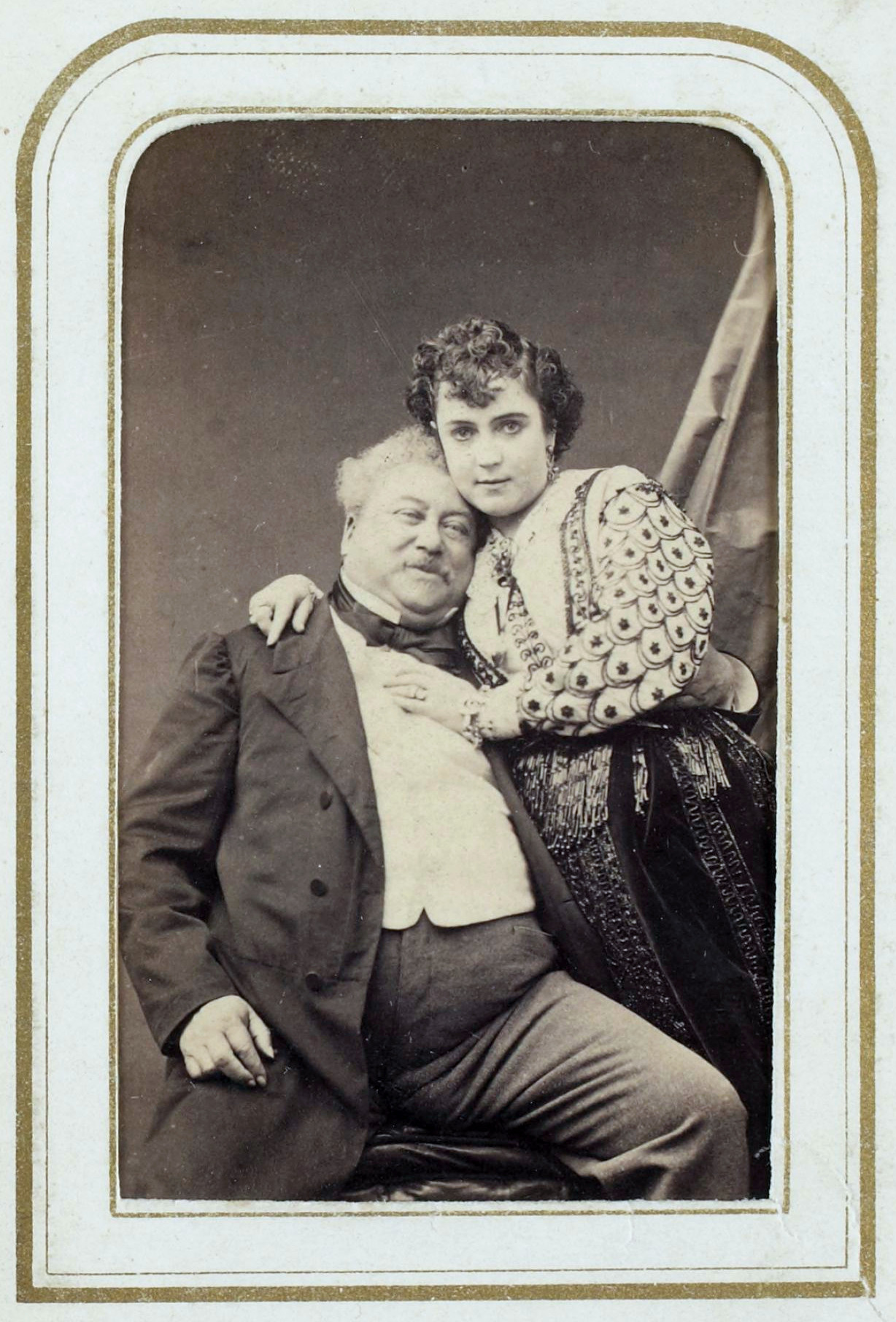

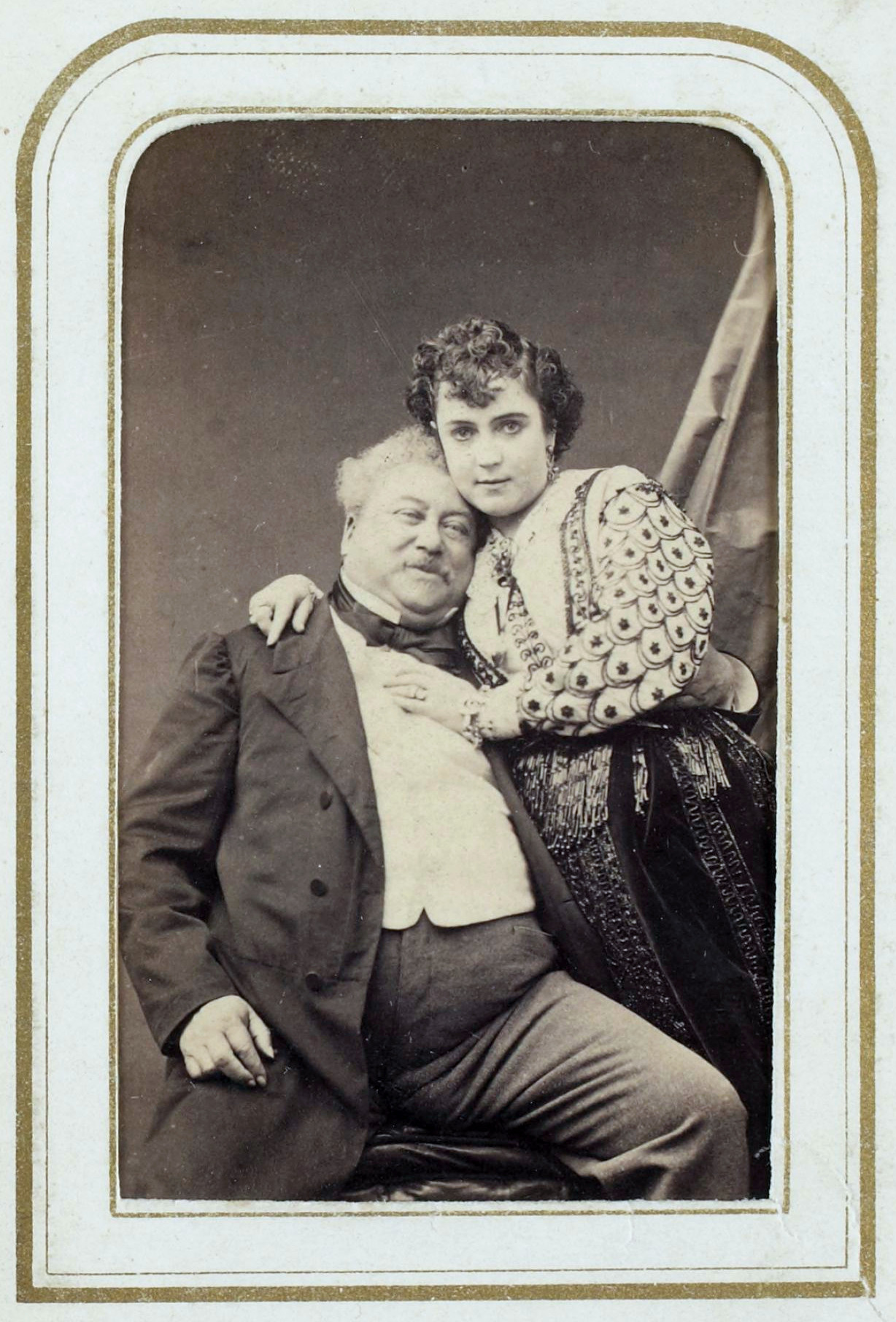

Playing in a sold-out run of ''Les pirates de la savane'' in Paris in 1866, Menken had an affair with the French novelist

Playing in a sold-out run of ''Les pirates de la savane'' in Paris in 1866, Menken had an affair with the French novelist Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas (, ; ; born Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie (), 24 July 1802 – 5 December 1870), also known as Alexandre Dumas père (where '' '' is French for 'father', to distinguish him from his son Alexandre Dumas fils), was a French writer ...

, père, considered somewhat scandalous as he was more than twice her age. Returning to England in 1867, she struggled to attract audiences to ''Mazeppa'' and attendance fell off. During this time she had an affair with the English poet Algernon Charles Swinburne

Algernon Charles Swinburne (5 April 1837 – 10 April 1909) was an English poet, playwright, novelist, and critic. He wrote several novels and collections of poetry such as ''Poems and Ballads'', and contributed to the famous Eleventh Edition ...

.

She fell ill in London and was forced to stop performing, struggling with poverty as a result. Few realized that the glamorous star was ill until she collapsed during rehearsal and died a few weeks later. She began preparing her poems for publication and moved back to Paris, where she died on August 10, 1868. She had just written to a friend:

I am lost to art and life. Yet, when all is said and done, have I not at my age tasted more of life than most women who live to be a hundred? It is fair, then, that I should go where old people go.How long she had been a consumptive no one knew but, from what is known, she was dead at 33 – the flamelike quality that Dickens had called the “world’s delight” extinguished forever. They buried her in a corner of the little Jewish cemetery in Montparnasse, and on her grave stone are the words, “Thou Knowest,” an epitaph she had chosen from Swinburne, the poet who had said of her, “A woman who has such beautiful legs need not discuss poetry.” She was believed to have died of

peritonitis

Peritonitis is inflammation of the localized or generalized peritoneum, the lining of the inner wall of the abdomen and cover of the abdominal organs. Symptoms may include severe pain, swelling of the abdomen, fever, or weight loss. One part or ...

and/or tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

,. Late twentieth-century sources suggest she had cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

. She was buried in Montparnasse Cemetery

Montparnasse Cemetery (french: link=no, Cimetière du Montparnasse) is a cemetery in the Montparnasse quarter of Paris, in the city's 14th arrondissement. The cemetery is roughly 47 acres and is the second largest cemetery in Paris. The cemetery ...

.

The inscription on her tomb read - "Thou knowest." In 1862, Menken had written about her public and private personae:

I have always believed myself to be possessed of two souls, one that lives on the surface of life, pleasing and pleased; the other as deep and as unfathomable as the ocean; a mystery to me and all who know me.Her only book, ''Infelicia'', a collection of 31 poems, was published several days after her death.

Literary career

Menken wanted to be known as a writer, but her work was overshadowed by her sensational stage career and private and public life. In total, she published about 20 essays, 100 poems and a book of her collected poems, from 1855 to 1868; the book was published posthumously. Her work was not received well by contemporary critics. George Merriam Hyde, one of the most respected critics of his day, refused to critique Menken's work, saying (privately) that "it would be an insult to himself and his profession".Van Wyck Brooks

Van Wyck Brooks (February 16, 1886 in Plainfield, New Jersey – May 2, 1963 in Bridgewater, Connecticut) was an American literary critic, biographer, and historian.

Biography

Brooks graduated from Harvard University in 1908. As a studen ...

joked (in public) that "her work is the best example of unintentional wit and accidental humour".

Her early work was devoted to family and romance. After her marriage to Menken and her study of Judaism, her poetry and essays for years into the 1860s featured Jewish themes. After her marriage and divorce from Heenan and meeting with writers in New York, she changed her style, adopting some influence from Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among t ...

. She was said to be the "first poet and the only woman poet before the twentieth century" to follow his lead in using free verse. ''The New York Times'' reported that Walt Whitman had disassociated himself from Menken's work, implying he thought little of it.

Beginning in New York, her poetry expressed a wider range of emotions related to relationships, sexuality, and also about women's struggle to find a place in the world. Her collection ''Infelicia'' went through several editions and was in print until 1902. In the late nineteenth century, critics were hard on women writers, and Menken's public notoriety caused even more critical scrutiny of her poems. Later critics (such as A. R. Lloyd in his book, ''The Great Prize Fight'' and Graham Gordon in his book ''Master of the Ring'') generally dismiss her work as being devoid of talent. Admirers included Christina Rossetti

Christina Georgina Rossetti (5 December 1830 – 29 December 1894) was an English writer of romantic, devotional and children's poems, including "Goblin Market" and "Remember". She also wrote the words of two Christmas carols well known in Brit ...

and Joaquin Miller

Cincinnatus Heine Miller (; September 8, 1837 – February 17, 1913), better known by his pen name Joaquin Miller (), was an American poet, author, and frontiersman. He is nicknamed the "Poet of the Sierras" after the Sierra Nevada, about which h ...

.

References

Further reading

* Abernethy, Francis Edward, ed. (1981). ''Legendary Ladies of Texas''. ''Adah Isaacs Menken: From Texas to Paris, Pamela Lynn Palmer''. Publications of the Texas Folklore Society, 43. Dallas: E-Heart. * * Brooks, Elizabeth (1896). ''Prominent Women of Texas''. Akron, Ohio: Werner Publishing. * Cofran, John (May 1990). ''The Identity of Adah Isaacs Menken: A Theatrical Mystery Solved''. Theatre Survey. 31. * * * * Eichin, Carolyn Grattan (2020). ''From San Francisco Eastward: Victorian Theater in the American West''. Reno, Nevada:University of Nevada Press

University of Nevada Press is a university press that is run by the Nevada System of Higher Education (NSHE). Its authority is derived from the Nevada state legislature and Board of Regents of the NSHE. It was founded by Robert Laxalt in 1961. T ...

.

*

*

*

*

External links

"Adah Isaacs Menken (Bertha Theodore) (1835–1868)"

''The Vault at Pfaff's'', hosted at Lehigh University, includes several photos *

Charles Warren Stoddard

Charles Warren Stoddard (August 7, 1843 April 23, 1909) was an American author and editor best known for his travel books about Polynesian life.

Biography

Charles Warren Stoddard was born in Rochester, New York on August 7, 1843. He was desce ...

"La Belle Menken"

''National Magazine'', 1905, at Open Archive, includes several photos

Jewish Virtual Library, 2012 * 21 photos, including one with

Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas (, ; ; born Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie (), 24 July 1802 – 5 December 1870), also known as Alexandre Dumas père (where '' '' is French for 'father', to distinguish him from his son Alexandre Dumas fils), was a French writer ...

, Billy Rose

Billy Rose (born William Samuel Rosenberg; September 6, 1899 – February 10, 1966) was an American impresario, theatrical showman and lyricist. For years both before and after World War II, Billy Rose was a major force in entertainment, with sh ...

Collection

*

*

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Menken, Adah

Vaudeville performers

Actresses from New Orleans

Louisiana Creole people

19th-century American actresses

American stage actresses

Jewish American poets

Converts to Judaism

1835 births

1868 deaths

Writers from New Orleans

Burials at Montparnasse Cemetery

19th-century American poets

19th-century American women writers

African-American Jews

People working with horses