Action At Sihayo's Kraal on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 12 January 1879 action at Sihayo's Kraal was an early skirmish in the

On 11 January 1879 the ultimatum expired and British forces, under

On 11 January 1879 the ultimatum expired and British forces, under

The NNC became pinned down but Hamilton-Browne led one company, to assault the Zulus in the rough ground. The assault was successful in clearing the base of the gorge, and capturing a number of women and children, who were sent to the rear. The Zulu warriors retreated up steep path leading to the top of the cliffs.

The path was barricaded and covered by concealed marksmen and, seeing the NNC falter, Black and a staff officer, Captain Henry Harford moved forward to support Hamilton-Browne. On the way Harford spotted a Zulu taking aim at Glyn, who was observing from open ground, and shouted a warning, preventing his injury or death. Black moved between parties of the NNC trying, largely in vain, to encourage them forwards. Attempts by the NNC non-commissioned officers to force their men forwards by clubbing them with rifle butts also failed. Harford rallied a group of NNC men and made some forward progress, clearing caves in the cliff face. The men of the 24th also advanced, their rifles with fixed-bayonets proving an encouragement to the NNC.

The men of the NNC with rifles opened fire, causing the company under Hamilton-Browne at the foot of the cliffs, who were also under fire from the Zulus, to take cover. Black once more tried to lead the NNC in an attack; waving his hat over his head in one hand and brandishing his sword in the other. Black's hat was shot out of his hand and he was struck "below the belt" by a boulder thrown from the cliffs, causing pain but no injury and halting his advance.

Part of the 2nd Battalion of the NNC was also brought up in support but the action on the low ground was over by 9:00 a.m., as the NNC and men from the 24th Regiment climbed the cliffs elsewhere and outflanked the Zulus holding the path. At least a dozen Zulus were killed in action in the gorge along with two NNC men; around twenty NNC men and three of their European officers and non-commissioned officers were wounded.

In the meantime Russell's mounted contingent had also reached the heights. His force was split in two with the Natal Mounted Police and Natal Carbineers on the left and the other men on the right, out of sight on one another. The left unit came under fire from a party of 60 Zulus in rocky ground. They dismounted and advanced in skirmish order, returning fire. The Zulus were driven off by 10.00 am, with losses of 10-18 dead and no British casualties. The right-hand party captured a number of Zulu horses but otherwise had an uneventful day, except for narrowly avoiding a friendly fire incident with a party of the NNC who had removed their distinguishing red headbands to avoid attack by the Zulus.

The NNC became pinned down but Hamilton-Browne led one company, to assault the Zulus in the rough ground. The assault was successful in clearing the base of the gorge, and capturing a number of women and children, who were sent to the rear. The Zulu warriors retreated up steep path leading to the top of the cliffs.

The path was barricaded and covered by concealed marksmen and, seeing the NNC falter, Black and a staff officer, Captain Henry Harford moved forward to support Hamilton-Browne. On the way Harford spotted a Zulu taking aim at Glyn, who was observing from open ground, and shouted a warning, preventing his injury or death. Black moved between parties of the NNC trying, largely in vain, to encourage them forwards. Attempts by the NNC non-commissioned officers to force their men forwards by clubbing them with rifle butts also failed. Harford rallied a group of NNC men and made some forward progress, clearing caves in the cliff face. The men of the 24th also advanced, their rifles with fixed-bayonets proving an encouragement to the NNC.

The men of the NNC with rifles opened fire, causing the company under Hamilton-Browne at the foot of the cliffs, who were also under fire from the Zulus, to take cover. Black once more tried to lead the NNC in an attack; waving his hat over his head in one hand and brandishing his sword in the other. Black's hat was shot out of his hand and he was struck "below the belt" by a boulder thrown from the cliffs, causing pain but no injury and halting his advance.

Part of the 2nd Battalion of the NNC was also brought up in support but the action on the low ground was over by 9:00 a.m., as the NNC and men from the 24th Regiment climbed the cliffs elsewhere and outflanked the Zulus holding the path. At least a dozen Zulus were killed in action in the gorge along with two NNC men; around twenty NNC men and three of their European officers and non-commissioned officers were wounded.

In the meantime Russell's mounted contingent had also reached the heights. His force was split in two with the Natal Mounted Police and Natal Carbineers on the left and the other men on the right, out of sight on one another. The left unit came under fire from a party of 60 Zulus in rocky ground. They dismounted and advanced in skirmish order, returning fire. The Zulus were driven off by 10.00 am, with losses of 10-18 dead and no British casualties. The right-hand party captured a number of Zulu horses but otherwise had an uneventful day, except for narrowly avoiding a friendly fire incident with a party of the NNC who had removed their distinguishing red headbands to avoid attack by the Zulus.

The British commanders were reasonably pleased with the day's events and considered that the NNC had performed well in their first action. The total Zulu casualties were estimated at thirty killed, including Mkumbikazulu kaSihayo, and four wounded who were captured. At least three unwounded Zulus were taken prisoner by an NNC officer. The prisoners were interrogated with physical violence but did not reveal the presence of the Zulu field army, 25,000 warriors and 10,000 followers and reserves, which was then at a position just over from the Centre Column. The able-bodied prisoners were released on 13 January and took refuge at Sotondose's Drift. Chelmsford's orders were to release the wounded prisoners once they had recovered. One of the prisoners received treatment at the British hospital at Rorke's Drift and was killed by the Zulu when they stormed the hospital during the Battle of Rorke's Drift on 22/23 January.

The British commanders were reasonably pleased with the day's events and considered that the NNC had performed well in their first action. The total Zulu casualties were estimated at thirty killed, including Mkumbikazulu kaSihayo, and four wounded who were captured. At least three unwounded Zulus were taken prisoner by an NNC officer. The prisoners were interrogated with physical violence but did not reveal the presence of the Zulu field army, 25,000 warriors and 10,000 followers and reserves, which was then at a position just over from the Centre Column. The able-bodied prisoners were released on 13 January and took refuge at Sotondose's Drift. Chelmsford's orders were to release the wounded prisoners once they had recovered. One of the prisoners received treatment at the British hospital at Rorke's Drift and was killed by the Zulu when they stormed the hospital during the Battle of Rorke's Drift on 22/23 January.

The British captured 13 horses, 413 cattle, 332 goats and 235 sheep with some of these being driven into Natal. The British soldiers were pleased with this as they anticipated payment of

The British captured 13 horses, 413 cattle, 332 goats and 235 sheep with some of these being driven into Natal. The British soldiers were pleased with this as they anticipated payment of  Sihayo and his senior son, Mehlokazulu, missed the action, having left the day before with the bulk of his fighting men to answer Cetshwayo's call to arms at Ulundi. He had left just 200-300 men to defend his kraal. News of the attack reached the Zulu king whilst he was considering which of the three British columns to engage with his main force. The action seems to have convinced him to attack the Centre Column. Cetshwayo may have been persuaded that the Centre Column was the most important of the British forces by the presence of Chelmsford directing the attack. Cetshwayo sent the bulk of his army against it and part of Chelmsford's force was subsequently annihilated at the

Sihayo and his senior son, Mehlokazulu, missed the action, having left the day before with the bulk of his fighting men to answer Cetshwayo's call to arms at Ulundi. He had left just 200-300 men to defend his kraal. News of the attack reached the Zulu king whilst he was considering which of the three British columns to engage with his main force. The action seems to have convinced him to attack the Centre Column. Cetshwayo may have been persuaded that the Centre Column was the most important of the British forces by the presence of Chelmsford directing the attack. Cetshwayo sent the bulk of his army against it and part of Chelmsford's force was subsequently annihilated at the

Anglo-Zulu War

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in 1879 between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. Following the passing of the British North America Act of 1867 forming a federation in Canada, Lord Carnarvon thought that a similar political effort, coupl ...

. The day after launching an invasion of Zululand, the British Lieutenant-General Lord Chelmsford

Viscount Chelmsford, of Chelmsford in the County of Essex, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1921 for Frederic Thesiger, 3rd Baron Chelmsford, the former Viceroy of India. The title of Baron Chelmsford, of Chelm ...

led a reconnaissance in force

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops (skirmishers, ...

against the kraal

Kraal (also spelled ''craal'' or ''kraul'') is an Afrikaans and Dutch word, also used in South African English, for an enclosure for cattle or other livestock, located within a Southern African settlement or village surrounded by a fence of th ...

of Zulu Chief Sihayo kaXongo

Sihayo kaXongo (c. 1824 – 2 July 1883) was a Zulu inKosi (chief). In some contemporary British documents he is referred to as Sirhayo or Sirayo. He was an inDuna (commander) of the iNdabakawombe iButho (social age group and regiment) and supp ...

. This was intended to secure his left flank for an advance on the Zulu capital at Ulundi and as retribution against Sihayo for the incursion of his sons into the neighbouring British Colony of Natal.

En-route to the kraal the British force found a small party of Zulus in a horseshoe-shaped gorge. A frontal assault was launched by auxiliary troops from the Natal Native Contingent (NNC), supported by British regulars, while a mixed unit of mounted infantry moved onto the high ground to the rear of the Zulus. After the NNC attack faltered the regulars reinvigorated the attack and defeated the Zulus in the gorge. The mounted force engaged around sixty Zulus on the high ground and drove them off. The Zulu force suffered losses of 40 killed, 4 wounded and at least 3 captured. The British lost 2 members of the NNC killed and 22 wounded.

After their victory the British moved on Sihayo's Kraal, which they found to be undefended. After burning it down they returned to their camp. The action is believed to have led Cetshwayo to attack Chelmsford's force in preference to the two other British columns operating in Zululand. Much of Chelmford's column was destroyed at the Battle of Isandlwana

The Battle of Isandlwana (alternative spelling: Isandhlwana) on 22 January 1879 was the first major encounter in the Anglo-Zulu War between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. Eleven days after the British commenced their invasion of Zulul ...

ten days later.

Background

In the 1870s the British government sought to extend its control over Southern Africa. Apart from the valuable naval base at theCape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

they had previously shown little interest in the region but this changed with the discovery of valuable mineral deposits. In 1877 Sir Henry Bartle Frere

Sir Henry Bartle Edward Frere, 1st Baronet, (29 March 1815 – 29 May 1884) was a Welsh British colonial administrator. He had a successful career in India, rising to become Governor of Bombay (1862–1867). However, as High Commissioner for ...

was dispatched as High Commissioner for Southern Africa with a mandate to bring the existing colonies, indigenous African groups and the Boer republics under British authority. Frere viewed the independent Zulu Kingdom

The Zulu Kingdom (, ), sometimes referred to as the Zulu Empire or the Kingdom of Zululand, was a monarchy in Southern Africa. During the 1810s, Shaka established a modern standing army that consolidated rival clans and built a large following ...

as a possible threat to this plan and sought an excuse to declare war and annex it. He established a boundary commission to look into a dispute between Zululand and the Boer Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

, which had been recently annexed by the British, hoping for an outcome that would enrage the Zulu king, Cetshwayo. However, when the report was produced it largely backed the Zulu claim.

Frere instead seized on an incident in July 1878. Two wives of Zulu chief Sihayo kaXongo

Sihayo kaXongo (c. 1824 – 2 July 1883) was a Zulu inKosi (chief). In some contemporary British documents he is referred to as Sirhayo or Sirayo. He was an inDuna (commander) of the iNdabakawombe iButho (social age group and regiment) and supp ...

fled from his kraal

Kraal (also spelled ''craal'' or ''kraul'') is an Afrikaans and Dutch word, also used in South African English, for an enclosure for cattle or other livestock, located within a Southern African settlement or village surrounded by a fence of th ...

(homestead) into the British colony of Natal. Two of Sihayo's sons crossed into Natal with an armed band, seized the women and returned them to Zululand where they were executed. Frere mobilised British troops on the border and requested a meeting with Cetshwayo's representatives in December, ostensibly to discuss the report of the boundary commission. Frere instead presented them with an ultimatum. Cetshwayo was required to turn over Sihayo's sons to face British justice and turn over the chief Mbilini waMswati Prince Mbilini, otherwise known as ''Mbilini waMswati'', was a Swazi prince and son of Mswati II. Mbilini was a pretender to the Swazi throne after the death of King Mswati II. His brother Mbandzeni was the recognised king after the death of their h ...

to the Transvaal courts for raiding as well as paying a fine of cattle for these offenses and the 1878 Natal–Zululand border incident. Frere also demanded wholesale changes to the Zulu system of government including limits on the use of the death penalty, the requirement for judicial trials, supervision by a British official, admission of Christian missionaries and the abolition of the Zulu social/army system and the associated restrictions on marriage. The ultimatum was harsh, demanding radical change in the Zulu way of life, and it was intended by Frere that Cetshwayo would reject it. Emissaries sent by Cetshwayo requesting an extension to the ultimatum deadline were ignored.

On 11 January 1879 the ultimatum expired and British forces, under

On 11 January 1879 the ultimatum expired and British forces, under Lieutenant-General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Lord Chelmsford

Viscount Chelmsford, of Chelmsford in the County of Essex, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1921 for Frederic Thesiger, 3rd Baron Chelmsford, the former Viceroy of India. The title of Baron Chelmsford, of Chelm ...

entered Zululand in three columns. One column operated close to the eastern coastline and one advanced from Transvaal in the west. The main force, the Centre Column under Chelmsford, crossed the Buffalo River into Zulu territory at Rorke's Drift

The Battle of Rorke's Drift (1879), also known as the Defence of Rorke's Drift, was an engagement in the Anglo-Zulu War. The successful British defence of the mission station of Rorke's Drift, under the command of Lieutenants John Chard of the ...

and made camp on the far side. On 6 January Chelmsford had written to Frere that he had received reports that Sihayo had assembled 8,000 men to attack the British when they made their crossing, but it was unopposed.

Chelmsford determined to attack Sihayo's Kraal which lay some from his camp. He intended this to secure his left flank for the advance upon the Zulu capital of Ulundi and as a punitive measure against Sihayo. Chelmsford thought that an attack on Sihayo would show the British government that he was acting against the Zulu leadership, particularly those mentioned in the ultimatum, and not against the Zulu people in general. A reconnaissance party of the Natal Mounted Police under Major John Dartnell were dispatched on the first day of the invasion. Dartnell's force approached Sihayo's Kraal along the Bashee River valley and returned to Chelmsford's camp by that evening, he reported hearing war songs being sung by a large party of Zulu in the valley but could not locate them. Other scouting parties sent out in other directions captured a large number of Zulu cattle.

Advance

Chelmsford ordered a force, commanded byColonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

Richard Thomas Glyn

Lt Gen Richard Thomas Glyn (23 December 1831 – 21 November 1900) was a British Army officer. He joined the 82nd Regiment of Foot (Prince of Wales's Volunteers) by purchasing an ensign's commission in 1850. Glyn served with the regiment in the ...

of the 24th Regiment of Foot

Fourth or the fourth may refer to:

* the ordinal form of the number 4

* ''Fourth'' (album), by Soft Machine, 1971

* Fourth (angle), an ancient astronomical subdivision

* Fourth (music), a musical interval

* ''The Fourth'' (1972 film), a Sovie ...

, to leave the camp at 3:30 a.m. on 12 January; this was later described as a reconnaissance in force

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops (skirmishers, ...

. Glyn's command was a mixed force of men from his regiment; auxiliary troops of the 3rd Regiment Natal Native Contingent (NNC), commanded by Major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

Wilsone Black; and some irregular mounted infantry, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colonel. ...

John Cecil Russell

Major-General John Cecil Russell (1839–1909) was a British cavalry officer. After a brief service with the Oxford University Rifle Volunteer Corps Russell purchased a commission in the 11th Light Dragoons in 1860. He transferred to the 10 ...

. Chelmsford accompanied the force. Glyn was in formal command but Chelmsford was prone to interfere in tactical matters and helped direct the movement of the column. This practice led to uncertainty over the division of responsibility in the column, not helped by a personal rift between Glyn's chief of staff

The title chief of staff (or head of staff) identifies the leader of a complex organization such as the armed forces, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a principal staff officer (PSO), who is the coordinator of the supporti ...

Major Francis Clery

Major-General Sir Cornelius Francis Clery (13 February 1838 – 25 June 1926) was a British Army officer who took part in the Anglo-Zulu War and later commanded the 2nd Division during the Second Boer War.

Early life

Cornelius Frances Clery w ...

and Chelmsford's, Lieutenant-Colonel John North Crealock.

The British troops proceeded north-east from the camp keeping to a track on the west side of the Bashee River. After around a quantity of cattle and other livestock were observed on the far side with a number of Zulus to the hills above them. Chelmsford ordered the force to cross the river and prepare for action. Whilst Glyn and Chelmsford consulted on their battle plan, the Zulus taunted the British, shouting "Why are you waiting there? Are you looking to build kraals? Why don't you come on up?"

Action

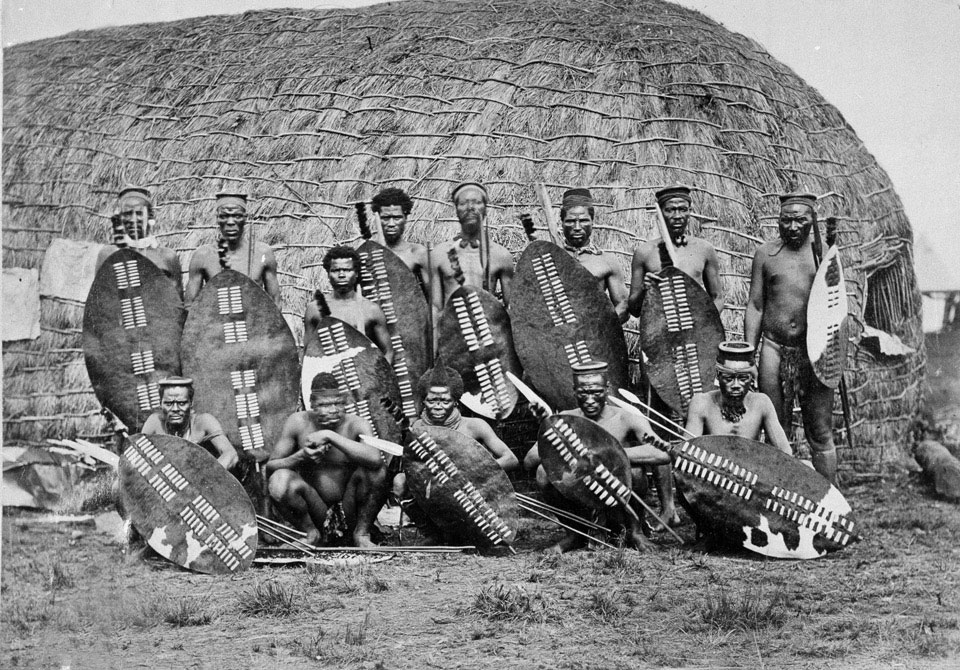

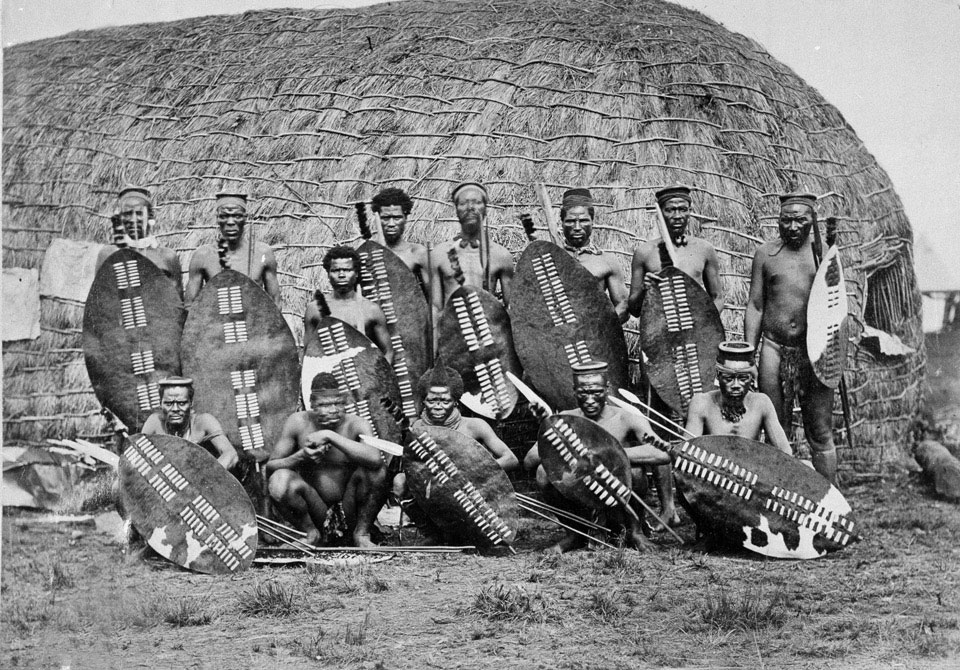

The Zulu defenders were commanded by Mkumbikazulu kaSihayo, one of Sihayo's sons involved in the Natal raid. They held a horseshoe-shaped gorge on a steep hillside, part of Ngedla Hill. The open end of the gorge faced towards the Bashee River and the base of the cliffs were covered with boulders and scrub. Sihayo's kraal lay further to the north on a more gently sloping part of the Ngedla. Chelmsford and Glyn determined to clear the Zulu from the gorge before proceeding to the kraal to burn it. Chelmsford ordered Russell's mounted infantry to move to the south where the slope was climbable and to sweep around behind the Zulus on the heights to threaten them and cut off any retreat. In the meantime the entire 1st battalion of the 3rdregiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscripted ...

of the Natal Native Contingent (under Commandant George Hamilton-Browne

George Hamilton-Browne (22 December 1844 – 21 January 1916) was a British irregular soldier, adventurer, writer and impostor. He was born into a military family of Irish descent in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire on 22 December 1844. He was the son ...

) were to assault the Zulus on the lower ground and attempt to seize the cattle, they would be supported by three companies of the 1st battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

of the 24th Regiment (commanded by Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

William Degacher). The 2nd battalion of the 3rd regiment of the Natal Native Contingent (commanded by Commandant Edward Russell Cooper) and additional men from the 24th Regiment of Foot, including four companies of the 2nd battalion, were held in reserve.

The NNC, under Hamilton-Browne, led the attack, beginning probably a little after 8.00 am. He had been ordered by Chelmsford not to open fire before the Zulu did and to avoid harming any Zulu women or children. Hamilton-Browne was worried about the prospect of friendly fire from his poorly trained men and ordered them not to use their firearms at all. The NNC had received little training in military drill

A drill is a tool or machine for cutting holes in a material.

Drill may also refer to:

Animals

* Drill (animal), a type of African primate

* Oyster drill, a type of snail

Military

* Military exercise

* Foot drill, the movements performed on a p ...

and Hamilton-Browne's non-commissioned officers soon gave up attempts to keep the NNC in line during their advance.

As the British column approached the Zulu herdsmen drove the livestock deeper into the gorge and raised the alarm. The NNC were in good spirits until they came within gunshot of the "several score" Zulu warriors who were hiding among boulders, shrubs and caves at the edges of the gorge. At this point they were challenged by a Zulu shouting "By whose orders do you come to the land of the Zulus?". A newspaper reporter with the British, Charles Norris-Newman, recorded that no reply was made but Hamilton-Browne claimed that his interpreter, Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

R. Duncombe, replied "By the orders of the Great White Queen". The Zulus then opened fire on the British right flank, their first shot striking an NNC man and breaking his thigh bone.

The NNC became pinned down but Hamilton-Browne led one company, to assault the Zulus in the rough ground. The assault was successful in clearing the base of the gorge, and capturing a number of women and children, who were sent to the rear. The Zulu warriors retreated up steep path leading to the top of the cliffs.

The path was barricaded and covered by concealed marksmen and, seeing the NNC falter, Black and a staff officer, Captain Henry Harford moved forward to support Hamilton-Browne. On the way Harford spotted a Zulu taking aim at Glyn, who was observing from open ground, and shouted a warning, preventing his injury or death. Black moved between parties of the NNC trying, largely in vain, to encourage them forwards. Attempts by the NNC non-commissioned officers to force their men forwards by clubbing them with rifle butts also failed. Harford rallied a group of NNC men and made some forward progress, clearing caves in the cliff face. The men of the 24th also advanced, their rifles with fixed-bayonets proving an encouragement to the NNC.

The men of the NNC with rifles opened fire, causing the company under Hamilton-Browne at the foot of the cliffs, who were also under fire from the Zulus, to take cover. Black once more tried to lead the NNC in an attack; waving his hat over his head in one hand and brandishing his sword in the other. Black's hat was shot out of his hand and he was struck "below the belt" by a boulder thrown from the cliffs, causing pain but no injury and halting his advance.

Part of the 2nd Battalion of the NNC was also brought up in support but the action on the low ground was over by 9:00 a.m., as the NNC and men from the 24th Regiment climbed the cliffs elsewhere and outflanked the Zulus holding the path. At least a dozen Zulus were killed in action in the gorge along with two NNC men; around twenty NNC men and three of their European officers and non-commissioned officers were wounded.

In the meantime Russell's mounted contingent had also reached the heights. His force was split in two with the Natal Mounted Police and Natal Carbineers on the left and the other men on the right, out of sight on one another. The left unit came under fire from a party of 60 Zulus in rocky ground. They dismounted and advanced in skirmish order, returning fire. The Zulus were driven off by 10.00 am, with losses of 10-18 dead and no British casualties. The right-hand party captured a number of Zulu horses but otherwise had an uneventful day, except for narrowly avoiding a friendly fire incident with a party of the NNC who had removed their distinguishing red headbands to avoid attack by the Zulus.

The NNC became pinned down but Hamilton-Browne led one company, to assault the Zulus in the rough ground. The assault was successful in clearing the base of the gorge, and capturing a number of women and children, who were sent to the rear. The Zulu warriors retreated up steep path leading to the top of the cliffs.

The path was barricaded and covered by concealed marksmen and, seeing the NNC falter, Black and a staff officer, Captain Henry Harford moved forward to support Hamilton-Browne. On the way Harford spotted a Zulu taking aim at Glyn, who was observing from open ground, and shouted a warning, preventing his injury or death. Black moved between parties of the NNC trying, largely in vain, to encourage them forwards. Attempts by the NNC non-commissioned officers to force their men forwards by clubbing them with rifle butts also failed. Harford rallied a group of NNC men and made some forward progress, clearing caves in the cliff face. The men of the 24th also advanced, their rifles with fixed-bayonets proving an encouragement to the NNC.

The men of the NNC with rifles opened fire, causing the company under Hamilton-Browne at the foot of the cliffs, who were also under fire from the Zulus, to take cover. Black once more tried to lead the NNC in an attack; waving his hat over his head in one hand and brandishing his sword in the other. Black's hat was shot out of his hand and he was struck "below the belt" by a boulder thrown from the cliffs, causing pain but no injury and halting his advance.

Part of the 2nd Battalion of the NNC was also brought up in support but the action on the low ground was over by 9:00 a.m., as the NNC and men from the 24th Regiment climbed the cliffs elsewhere and outflanked the Zulus holding the path. At least a dozen Zulus were killed in action in the gorge along with two NNC men; around twenty NNC men and three of their European officers and non-commissioned officers were wounded.

In the meantime Russell's mounted contingent had also reached the heights. His force was split in two with the Natal Mounted Police and Natal Carbineers on the left and the other men on the right, out of sight on one another. The left unit came under fire from a party of 60 Zulus in rocky ground. They dismounted and advanced in skirmish order, returning fire. The Zulus were driven off by 10.00 am, with losses of 10-18 dead and no British casualties. The right-hand party captured a number of Zulu horses but otherwise had an uneventful day, except for narrowly avoiding a friendly fire incident with a party of the NNC who had removed their distinguishing red headbands to avoid attack by the Zulus.

Burning of the kraal

After the action a force of four companies of the 2/24th and part of the 2nd Battalion of the 3rd NNC, under the overall command of Colonel Henry Degacher of the 24th Regiment was sent to Sihayo's kraal with orders to raze it. The kraal was located further up the Bashee valley and above it. Degacher led a cautious advance in skirmish order. This was witnessed by men of the 1st battalion who, being on higher ground could see that the kraal was unoccupied and good humouredly mocked their comrades. Degacher's men then marched into the kraal and burnt it to the ground. Three old women and a young girl were found nearby but no male Zulu. The British soldiers recovered a number of Sihayo's carved prestige staffs from the kraal. The entire force marched back to its camp by the Buffalo River, reaching it by 4:00 p.m. The march was affected by a heavy thunderstorm and Chelmsford allowed the force a day off on 13 January to rest and dry their equipment. The force was afterwards engaged in guard duties, reconnaissance and preparing the roadway into Zululand. The force left camp early on 20 January and reached the next camp, at Isandlwana, by noon.Aftermath

The British commanders were reasonably pleased with the day's events and considered that the NNC had performed well in their first action. The total Zulu casualties were estimated at thirty killed, including Mkumbikazulu kaSihayo, and four wounded who were captured. At least three unwounded Zulus were taken prisoner by an NNC officer. The prisoners were interrogated with physical violence but did not reveal the presence of the Zulu field army, 25,000 warriors and 10,000 followers and reserves, which was then at a position just over from the Centre Column. The able-bodied prisoners were released on 13 January and took refuge at Sotondose's Drift. Chelmsford's orders were to release the wounded prisoners once they had recovered. One of the prisoners received treatment at the British hospital at Rorke's Drift and was killed by the Zulu when they stormed the hospital during the Battle of Rorke's Drift on 22/23 January.

The British commanders were reasonably pleased with the day's events and considered that the NNC had performed well in their first action. The total Zulu casualties were estimated at thirty killed, including Mkumbikazulu kaSihayo, and four wounded who were captured. At least three unwounded Zulus were taken prisoner by an NNC officer. The prisoners were interrogated with physical violence but did not reveal the presence of the Zulu field army, 25,000 warriors and 10,000 followers and reserves, which was then at a position just over from the Centre Column. The able-bodied prisoners were released on 13 January and took refuge at Sotondose's Drift. Chelmsford's orders were to release the wounded prisoners once they had recovered. One of the prisoners received treatment at the British hospital at Rorke's Drift and was killed by the Zulu when they stormed the hospital during the Battle of Rorke's Drift on 22/23 January.

The British captured 13 horses, 413 cattle, 332 goats and 235 sheep with some of these being driven into Natal. The British soldiers were pleased with this as they anticipated payment of

The British captured 13 horses, 413 cattle, 332 goats and 235 sheep with some of these being driven into Natal. The British soldiers were pleased with this as they anticipated payment of prize money

Prize money refers in particular to naval prize money, usually arising in naval warfare, but also in other circumstances. It was a monetary reward paid in accordance with the prize law of a belligerent state to the crew of a ship belonging to t ...

for the livestock. They were left disappointed when the animals were sold to army contractors at a low price. A number of obsolete firearms and a brand-new wagon were also recovered from Sihayo's Kraal.

Chelmsford wrote to Frere:

The engagement was reported in the ''Natal Times'' of 16 January as a victory over a Zulu attack. The newspaper mistakenly reported that one NNC officer was killed and two Natal Mounted Police members killed or wounded. It noted "the prediction of those best acquainted with the Zulus, that they would never stand the fire of regular forces, has been abundantly verified".

Battle of Isandlwana

The Battle of Isandlwana (alternative spelling: Isandhlwana) on 22 January 1879 was the first major encounter in the Anglo-Zulu War between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. Eleven days after the British commenced their invasion of Zulul ...

on 22 January. The prisoners released by Chelmsford on 13 January may have helped the inhabitants of Sotondose's Drift attack British survivors of the battle. The survivors of Sihayo's Kraal were certainly present, harassing the fleeing men and killing stragglers. The dead included Lieutenants Teignmouth Melvill

Teignmouth Melvill VC (8 September 1842 – 22 January 1879) was an officer in the British Army and recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British ...

and Nevill Coghill

Nevill Henry Kendal Aylmer Coghill (19 April 1899 – 6 November 1980) was an English literary scholar, known especially for his modern English version of Geoffrey Chaucer's ''Canterbury Tales''.

Life

His father was Sir Egerton Coghill, 5th ...

who were killed while trying to save the Queen's colour of the 1/24th and the drift afterwards became known as Fugitive's Drift.

Interpretation

The action at Sihayo's Kraal was the first of the war. Anglo-Zulu War historian Adrian Greaves, writing in 2012, regards the action at Sihayo's Kraal as a token victory against a small Zulu force consisting of old men and boys. He considers there was no military value to the engagement as Sihayo's warriors had already left the kraal to assemble with the main army and could not threaten Chelmsford's supply lines. Greaves thinks the action may have given Chelmsford false confidence that the Zulu would run from future engagements. Ian Knight considers that Chelmsford took the wrong lesson from the action, rather than noting the determination of the Zulu to hold their ground and the courage of their leaders (Mkumbikazulu having been killed leading his men), he focussed on the ease with which the Zulu had been defeated in a one-sided engagement. Knight thinks this led to a sense of complacency in the column, which may have had been a factor in their subsequent defeat at Isandlwana. The location of the action and Sihayo's Kraal is not certain as records kept by the British were vague and no battlefield relics have been recovered. The historian Keith Smith places Sihayo's Kraal at Sokhexe, a settlement still occupied by Sihayo's descendants and the earlier action at a location somewhat to the south near Ngedla hill.Notes

References

Citations

General sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{refend 1879 in the Zulu Kingdom Battles involving the United Kingdom Battles of the Anglo-Zulu War Conflicts in 1879 History of KwaZulu-Natal January 1879 events