Acrocanthosaurus Atokensis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Acrocanthosaurus'' ( ; ) is a

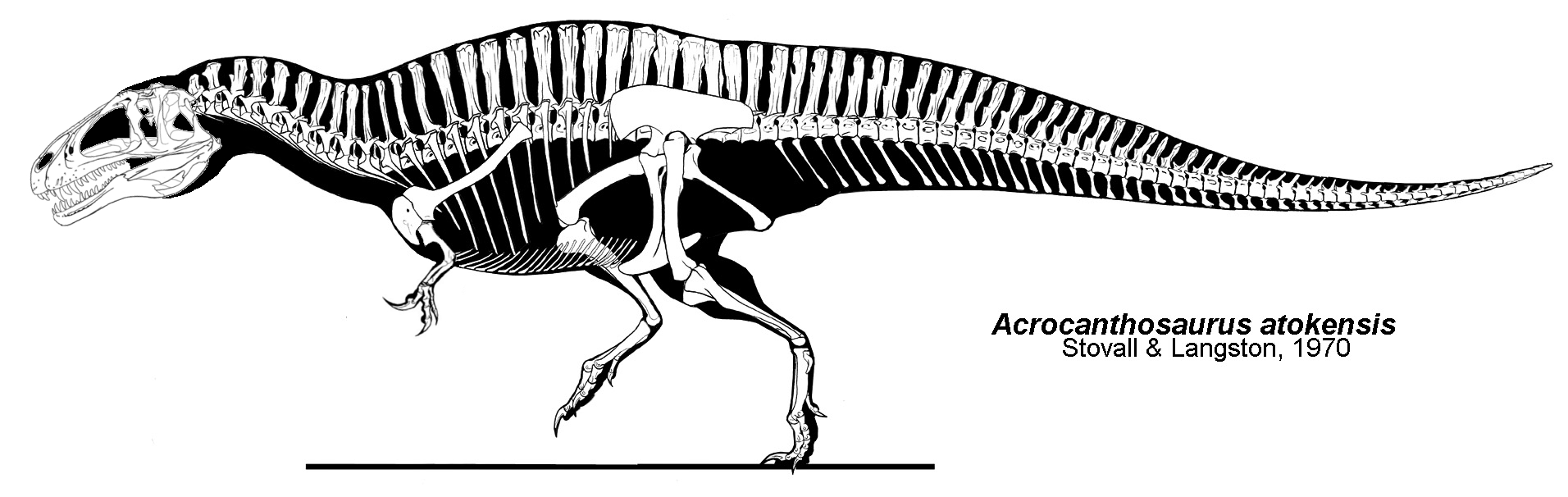

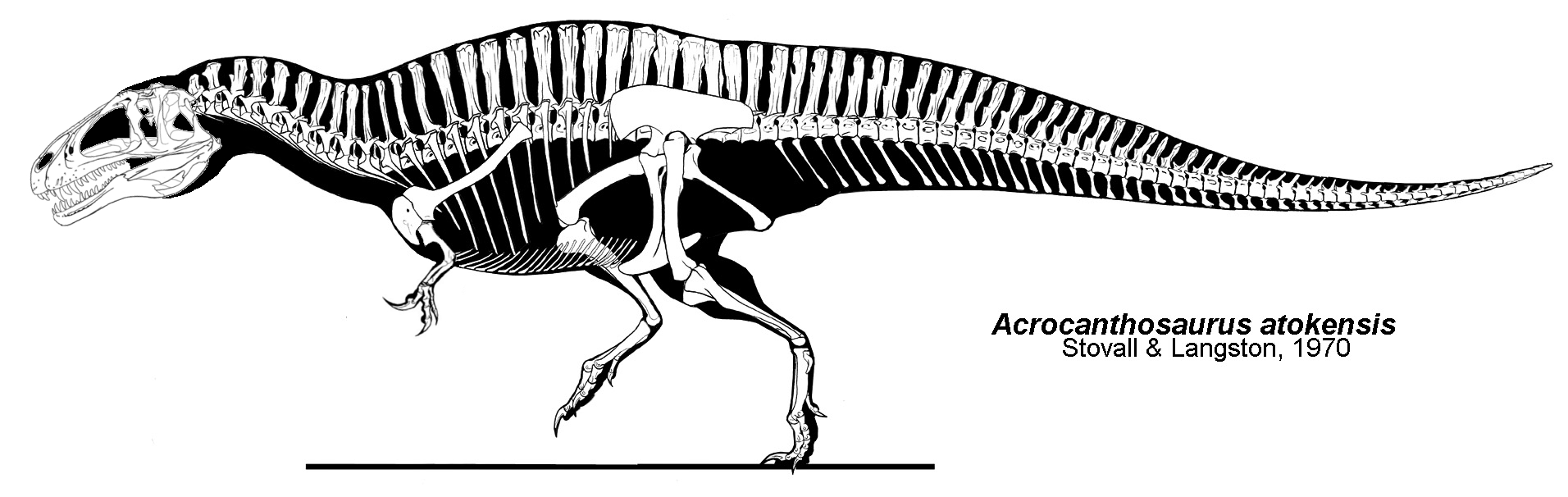

''Acrocanthosaurus'' was among the largest theropods known to exist, with an estimated

''Acrocanthosaurus'' was among the largest theropods known to exist, with an estimated

The most notable feature of ''Acrocanthosaurus'' was its row of tall neural spines, located on the vertebrae of the neck, back, hips and upper tail, which could be more than 2.5 times the height of the vertebrae from which they extended. Other dinosaurs also had high spines on the back, sometimes much higher than those of ''Acrocanthosaurus''. For instance, the African genus ''

The most notable feature of ''Acrocanthosaurus'' was its row of tall neural spines, located on the vertebrae of the neck, back, hips and upper tail, which could be more than 2.5 times the height of the vertebrae from which they extended. Other dinosaurs also had high spines on the back, sometimes much higher than those of ''Acrocanthosaurus''. For instance, the African genus ''

''Acrocanthosaurus'' is classified in the superfamily Allosauroidea within the

''Acrocanthosaurus'' is classified in the superfamily Allosauroidea within the

From the bone features of the

From the bone features of the

None of the

None of the

In 2005, scientists reconstructed an

In 2005, scientists reconstructed an

The

The

The skull of the ''Acrocanthosaurus atokensis''

The skull of the ''Acrocanthosaurus atokensis''

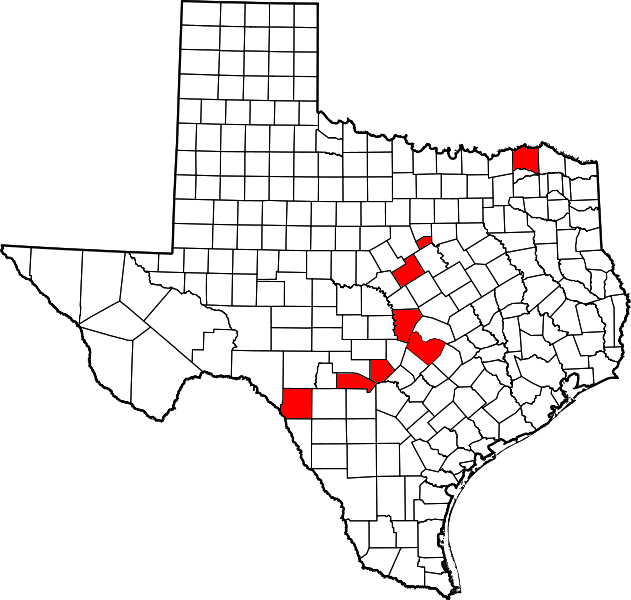

Definite ''Acrocanthosaurus'' fossils have been found in the

Definite ''Acrocanthosaurus'' fossils have been found in the

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

of carcharodontosaurid

Carcharodontosauridae (carcharodontosaurids; from the Greek καρχαροδοντόσαυρος, ''carcharodontósauros'': "shark-toothed lizards") is a group of carnivorous theropod dinosaurs. In 1931, Ernst Stromer named Carcharodontosauridae ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

that existed in what is now North America during the Aptian and early Albian

The Albian is both an age of the geologic timescale and a stage in the stratigraphic column. It is the youngest or uppermost subdivision of the Early/Lower Cretaceous Epoch/ Series. Its approximate time range is 113.0 ± 1.0 Ma to 100.5 ± 0 ...

stages of the Early Cretaceous, from 113 to 110 million years ago. Like most dinosaur genera, ''Acrocanthosaurus'' contains only a single species, ''A. atokensis''. Its fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

remains are found mainly in the U.S.

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

states of Oklahoma, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, and Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to the s ...

, although teeth attributed to ''Acrocanthosaurus'' have been found as far east as Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, suggesting a continent wide range.

''Acrocanthosaurus'' was a bipedal

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where an organism moves by means of its two rear limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped , meaning 'two feet' (from Latin ''bis'' 'double' ...

predator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill th ...

. As the name suggests, it is best known for the high neural spines

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates,Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristic ...

on many of its vertebra

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates, Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristi ...

e, which most likely supported a ridge of muscle over the animal's neck, back, and hips. ''Acrocanthosaurus'' was one of the largest theropods, with the largest known specimen reaching in length and weighing approximately . Large theropod footprints discovered in Texas may have been made by ''Acrocanthosaurus'', although there is no direct association with skeletal remains.

Recent discoveries have elucidated many details of its anatomy, allowing for specialized studies focusing on its brain

A brain is an organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It is located in the head, usually close to the sensory organs for senses such as vision. It is the most complex organ in a ve ...

structure and forelimb function. ''Acrocanthosaurus'' was the largest theropod in its ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syste ...

and likely an apex predator

An apex predator, also known as a top predator, is a predator at the top of a food chain, without natural predators of its own.

Apex predators are usually defined in terms of trophic dynamics, meaning that they occupy the highest trophic lev ...

which preyed on sauropods, ornithopod

Ornithopoda () is a clade of ornithischian dinosaurs, called ornithopods (), that started out as small, bipedal running grazers and grew in size and numbers until they became one of the most successful groups of herbivores in the Cretaceous wo ...

s, and ankylosaurs.

Discovery and naming

''Acrocanthosaurus'' is named after its tall neural spines, from theGreek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''ɑκρɑ''/''akra'' ('high'), ''ɑκɑνθɑ''/''akantha'' ('thorn' or 'spine') and ''σɑʊρος''/''sauros'' ('lizard'). There is one named species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

(''A. atokensis''), after Atoka County

Atoka County is a county located in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. As of the 2010 census, the population was 14,007. Its county seat is Atoka. The county was formed before statehood from Choctaw Lands, and its name honors a Choctaw Chief named ...

in Oklahoma, where the original specimens were found. The name was coined in 1950 by American paleontologists J. Willis Stovall and Wann Langston Jr. Langston had proposed the name "Acracanthus atokaensis" for the genus and species in his unpublished 1947 master's

A master's degree (from Latin ) is an academic degree awarded by universities or colleges upon completion of a course of study demonstrating mastery or a high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional practice.

thesis

A thesis ( : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: ...

, but the name was changed to ''Acrocanthosaurus atokensis'' for formal publication.

The holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of sever ...

and paratype

In zoology and botany, a paratype is a specimen of an organism that helps define what the scientific name of a species and other taxon actually represents, but it is not the holotype (and in botany is also neither an isotype nor a syntype). O ...

( OMNH 10146 and OMNH 10147), discovered in the early 1940s and described at the same time in 1950, consist of two partial skeletons and a piece of skull material from the Antlers Formation

The Antlers Formation is a stratum which ranges from Arkansas through southern Oklahoma into northeastern Texas. The stratum is thick consisting of silty to sandy mudstone and fine to coarse grained sandstone that is poorly to moderately sorted. ...

in Oklahoma. Two much more complete specimens were described in the 1990s. The first ( SMU 74646) is a partial skeleton, missing most of the skull, recovered from the Twin Mountains Formation

The Twin Mountains Formation, also known as the Twin Mak Formation, is a sedimentary rock formation, within the Trinity Group, found in Texas of the United States of America. It is a terrestrial formation of Aptian age (Lower Cretaceous), and ...

of Texas and currently part of the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History collection. An even more complete skeleton ( NCSM 14345, nicknamed "Fran") was recovered from the Antlers Formation of Oklahoma by Cephis Hall and Sid Love, prepared by the Black Hills Institute

The Black Hills Institute of Geological Research, Inc. (BHI) is a private corporation specializing in the excavation and preparation of fossils, as well as the sale of both original fossil material and museum-quality replicas. Founded in 1974 and b ...

in South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large porti ...

, and is now housed at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences

The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences (NCMNS) is the largest museum of its kind in the Southeastern United States. It is the oldest established museum in North Carolina, located in Raleigh. In 2013, it had about 1.2 million visitors, and i ...

in Raleigh

Raleigh (; ) is the capital city of the state of North Carolina and the seat of Wake County in the United States. It is the second-most populous city in North Carolina, after Charlotte. Raleigh is the tenth-most populous city in the Southeas ...

. The specimen is the largest and includes the only known complete skull and forelimb. Skeletal elements of OMNH 10147 are almost the same size as comparable bones in NCSM 14345, indicating an animal of roughly the same size, while the holotype and SMU 74646 are significantly smaller.

The presence of ''Acrocanthosaurus'' in the Cloverly Formation

The Cloverly Formation is a geological formation of Early and Late Cretaceous age (Valanginian to Cenomanian stage) that is present in parts of Montana, Wyoming, Colorado and Utah in the western United States. It was named for a post office on th ...

was established in 2012 with the description of another partial skeleton, UM 20796. The specimen, consisting of parts of two vertebrae, partial pubic bones

In vertebrates, the pubic region ( la, pubis) is the most forward-facing (ventral and anterior) of the three main regions making up the coxal bone. The left and right pubic regions are each made up of three sections, a superior ramus, inferior r ...

, a femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates wit ...

, a partial fibula

The fibula or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. Its upper extremity i ...

, and fragments, represents a juvenile animal. It came from a bonebed in the Bighorn Basin

The Bighorn Basin is a plateau region and intermontane basin, approximately 100 miles (160 km) wide, in north-central Wyoming in the United States. It is bounded by the Absaroka Range on the west, the Pryor Mountains on the north, the Bigho ...

of north-central Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to the s ...

, and was found near the shoulder blade of a ''Sauroposeidon

''Sauroposeidon'' ( ; meaning "lizard earthquake god", after the Greek god Poseidon) is a genus of sauropod dinosaur known from several incomplete specimens including a bone bed and fossilized trackways that have been found in the U.S. states of ...

''. An assortment of other fragmentary theropod remains from the formation may also belong to ''Acrocanthosaurus'', which may be the only large theropod in the Cloverly Formation.

''Acrocanthosaurus'' may be known from less complete remains outside of Oklahoma, Texas, and Wyoming. A tooth from southern Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

has been referred to the genus, and matching tooth marks have been found in sauropod bones from the same area. Several teeth from the Arundel Formation

The Arundel Formation, also known as the Arundel Clay, is a clay-rich sedimentary rock formation, within the Potomac Group, found in Maryland of the United States of America. It is of Aptian age (Lower Cretaceous). This rock unit had been econ ...

of Maryland have been described as almost identical to those of ''Acrocanthosaurus'' and may represent an eastern representative of the genus. Many other teeth and bones from various geologic formation

A geological formation, or simply formation, is a body of rock having a consistent set of physical characteristics ( lithology) that distinguishes it from adjacent bodies of rock, and which occupies a particular position in the layers of rock exp ...

s throughout the western United States have also been referred to ''Acrocanthosaurus'', but most of these have been misidentified; there is, however, some disagreement with this assessment regarding fossils from the Cloverly Formation.

Description

skull

The skull is a bone protective cavity for the brain. The skull is composed of four types of bone i.e., cranial bones, facial bones, ear ossicles and hyoid bone. However two parts are more prominent: the cranium and the mandible. In humans, th ...

length of and body length of based on the largest known specimen (NCSM 14345). The original describers of this specimen, Currie and Carpenter, considered its mass to be "lighter than ''Tyrannosaurus''", and Carpenter later proposed a body mass estimate of . With other researchers, Henderson initially estimated the body mass of this specimen at , but he later moderated it at . Bates and his colleagues in 2009 considered this an underestimate and produced a larger body mass estimate of within the range of , but their method is not tested for animals of large body mass, so some researchers consider it an exaggeration. Subsequent studies have yielded mass estimates between based on various techniques.

Skull

The skull of ''Acrocanthosaurus'', like most otherallosauroid

Allosauroidea is a superfamily or clade of theropod dinosaurs which contains four families — the Metriacanthosauridae, Allosauridae, Carcharodontosauridae, and Neovenatoridae. Allosauroids, alongside the family Megalosauroidea, were among ...

s, was long, low and narrow. The weight-reducing opening in front of the eye socket (antorbital fenestra

An antorbital fenestra (plural: fenestrae) is an opening in the skull that is in front of the eye sockets. This skull character is largely associated with archosauriforms, first appearing during the Triassic Period. Among extant archosaurs, bird ...

) was quite large, more than a quarter of the length of the skull and two-thirds of its height. The outside surface of the maxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. T ...

(upper jaw bone) and the upper surface of the nasal bone on the roof of the snout were not nearly as rough-textured as those of ''Giganotosaurus

''Giganotosaurus'' ( ) is a genus of theropod dinosaur that lived in what is now Argentina, during the early Cenomanian age of the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 99.6 to 95 million years ago. The holotype specimen was discovered in th ...

'' or ''Carcharodontosaurus

''Carcharodontosaurus'' (; ) is a genus of large carcharodontosaurid theropod dinosaur that existed during the Cenomanian age of the Late Cretaceous in Northern Africa. The genus ''Carcharodontosaurus'' is named after the shark genus '' Carc ...

''. Long, low ridges arose from the nasal bones, running along each side of the snout from the nostril back to the eye, where they continued onto the lacrimal bone

The lacrimal bone is a small and fragile bone of the facial skeleton; it is roughly the size of the little fingernail. It is situated at the front part of the medial wall of the orbit. It has two surfaces and four borders. Several bony landmarks of ...

s. This is a characteristic feature of all allosauroids. Unlike ''Allosaurus

''Allosaurus'' () is a genus of large carnosaurian theropod dinosaur that lived 155 to 145 million years ago during the Late Jurassic epoch ( Kimmeridgian to late Tithonian). The name "''Allosaurus''" means "different lizard" alludin ...

'', there was no prominent crest on the lacrimal bone in front of the eye. The lacrimal and postorbital

The ''postorbital'' is one of the bones in vertebrate skulls which forms a portion of the dermal skull roof and, sometimes, a ring about the orbit. Generally, it is located behind the postfrontal and posteriorly to the orbital fenestra. In some ...

bones met to form a thick brow over the eye, as seen in carcharodontosaurid

Carcharodontosauridae (carcharodontosaurids; from the Greek καρχαροδοντόσαυρος, ''carcharodontósauros'': "shark-toothed lizards") is a group of carnivorous theropod dinosaurs. In 1931, Ernst Stromer named Carcharodontosauridae ...

s and the unrelated abelisaurid

Abelisauridae (meaning "Abel's lizards") is a family (or clade) of ceratosaurian theropod dinosaurs. Abelisaurids thrived during the Cretaceous period, on the ancient southern supercontinent of Gondwana, and today their fossil remains are foun ...

s. Nineteen curved, serrated teeth

A tooth ( : teeth) is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, t ...

lined each side of the upper jaw, but a tooth count for the lower jaw has not been published. ''Acrocanthosaurus'' teeth were wider than those of ''Carcharodontosaurus'' and did not have the wrinkled texture that characterized the carcharodontosaurids. The dentary

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movable bone ...

(tooth-bearing lower jaw bone) was squared off at the front edge, as in ''Giganotosaurus'', and shallow, while the rest of the jaw behind it became very deep. ''Acrocanthosaurus'' and ''Giganotosaurus'' shared a thick horizontal ridge on the outside surface of the surangular

The suprangular or surangular is a jaw bone found in most land vertebrates, except mammals. Usually in the back of the jaw, on the upper edge, it is connected to all other jaw bones: dentary, angular, splenial and articular. It is often a mu ...

bone of the lower jaw, underneath the articulation with the skull.

Postcranial skeleton

The most notable feature of ''Acrocanthosaurus'' was its row of tall neural spines, located on the vertebrae of the neck, back, hips and upper tail, which could be more than 2.5 times the height of the vertebrae from which they extended. Other dinosaurs also had high spines on the back, sometimes much higher than those of ''Acrocanthosaurus''. For instance, the African genus ''

The most notable feature of ''Acrocanthosaurus'' was its row of tall neural spines, located on the vertebrae of the neck, back, hips and upper tail, which could be more than 2.5 times the height of the vertebrae from which they extended. Other dinosaurs also had high spines on the back, sometimes much higher than those of ''Acrocanthosaurus''. For instance, the African genus ''Spinosaurus

''Spinosaurus'' (; ) is a genus of spinosaurid dinosaur that lived in what now is North Africa during the Cenomanian to upper Turonian stages of the Late Cretaceous period, about 99 to 93.5 million years ago. The genus was known first f ...

'' had spines nearly tall, about 11 times taller than the bodies of its vertebrae. The lower spines of ''Acrocanthosaurus'' had attachments for powerful muscles like those of modern bison, probably forming a tall, thick ridge down its back. The function of the spines remains unknown, although they may have been involved in communication

Communication (from la, communicare, meaning "to share" or "to be in relation with") is usually defined as the transmission of information. The term may also refer to the message communicated through such transmissions or the field of inqui ...

, fat

In nutrition, biology, and chemistry, fat usually means any ester of fatty acids, or a mixture of such compounds, most commonly those that occur in living beings or in food.

The term often refers specifically to triglycerides (triple est ...

storage, muscle or temperature control

Temperature control is a process in which change of temperature of a space (and objects collectively there within), or of a substance, is measured or otherwise detected, and the passage of heat energy into or out of the space or substance is ad ...

. All of its cervical

In anatomy, cervical is an adjective that has two meanings:

# of or pertaining to any neck.

# of or pertaining to the female cervix: i.e., the ''neck'' of the uterus.

*Commonly used medical phrases involving the neck are

**cervical collar

**cerv ...

(neck) and dorsal

Dorsal (from Latin ''dorsum'' ‘back’) may refer to:

* Dorsal (anatomy), an anatomical term of location referring to the back or upper side of an organism or parts of an organism

* Dorsal, positioned on top of an aircraft's fuselage

* Dorsal c ...

(back) vertebrae had prominent depressions (pleurocoels

Skeletal pneumaticity is the presence of air spaces within bones. It is generally produced during development by excavation of bone by pneumatic diverticula (air sacs) from an air-filled space, such as the lungs or nasal cavity. Pneumatization is h ...

) on the sides, while the caudal (tail) vertebrae bore smaller ones. This is more similar to carcharodontosaurids than to ''Allosaurus''.

Aside from its vertebrae, ''Acrocanthosaurus'' had a typical allosauroid skeleton. ''Acrocanthosaurus'' was bipedal, with a long, heavy tail counterbalancing the head and body, maintaining its center of gravity

In physics, the center of mass of a distribution of mass in space (sometimes referred to as the balance point) is the unique point where the weighted relative position of the distributed mass sums to zero. This is the point to which a force ma ...

over its hips. Its forelimbs were relatively shorter and more robust than those of ''Allosaurus'' but were otherwise similar: each hand bore three clawed digits. Unlike many smaller fast-running dinosaurs, its femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates wit ...

was longer than its tibia

The tibia (; ), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outside of the tibia); it connects ...

and metatarsal

The metatarsal bones, or metatarsus, are a group of five long bones in the foot, located between the tarsal bones of the hind- and mid-foot and the phalanges of the toes. Lacking individual names, the metatarsal bones are numbered from the me ...

s, suggesting that ''Acrocanthosaurus'' was not a fast runner. Unsurprisingly, the hind leg bones of ''Acrocanthosaurus'' were proportionally more robust than its smaller relative ''Allosaurus''. Its feet had four digits each, although as is typical for theropods, the first was much smaller than the rest and did not make contact with the ground.

Classification and systematics

''Acrocanthosaurus'' is classified in the superfamily Allosauroidea within the

''Acrocanthosaurus'' is classified in the superfamily Allosauroidea within the infraorder

Order ( la, ordo) is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between family and class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and ...

Tetanurae

Tetanurae (/ˌtɛtəˈnjuːriː/ or "stiff tails") is a clade that includes most theropod dinosaurs, including megalosauroids, allosauroids, tyrannosauroids, ornithomimosaurs, compsognathids and maniraptorans (including birds). Tetanurans ar ...

. This superfamily is characterized by paired ridges on the nasal and lacrimal bones on top of the snout and tall neural spines on the neck vertebrae, among other features. It was originally placed in the family Allosauridae with ''Allosaurus'', an arrangement also supported by studies as late as 2000. Most studies have found it to be a member of the related family Carcharodontosauridae.

At the time of its discovery, ''Acrocanthosaurus'' and most other large theropods were known from only fragmentary remains, leading to highly variable classifications for this genus. J. Willis Stovall and Wann Langston Jr. first assigned it to the "Antrodemidae", the equivalent of Allosaurid

Allosauridae is a family of medium to large bipedal, carnivorous allosauroid theropod dinosaurs from the Late Jurassic. Allosauridae is a fairly old taxonomic group, having been first named by the American paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh in ...

ae, but it was transferred to the taxonomic wastebasket Megalosaurid

Megalosauridae is a monophyletic family of carnivorous theropod dinosaurs within the group Megalosauroidea. Appearing in the Middle Jurassic, megalosaurids were among the first major radiation of large theropod dinosaurs. They were a relative ...

ae by Alfred Sherwood Romer

Alfred Sherwood Romer (December 28, 1894 – November 5, 1973) was an American paleontologist and biologist and a specialist in vertebrate evolution.

Biography

Alfred Romer was born in White Plains, New York, the son of Harry Houston Romer an ...

in 1956. To other authors, the long spines on its vertebrae suggested a relationship with ''Spinosaurus

''Spinosaurus'' (; ) is a genus of spinosaurid dinosaur that lived in what now is North Africa during the Cenomanian to upper Turonian stages of the Late Cretaceous period, about 99 to 93.5 million years ago. The genus was known first f ...

''. This interpretation of ''Acrocanthosaurus'' as a spinosaurid

The Spinosauridae (or spinosaurids) are a clade or family of tetanuran theropod dinosaurs comprising ten to seventeen known genera. They came into prominence during the Cretaceous period. Spinosaurid fossils have been recovered worldwide, includi ...

persisted into the 1980s, and was repeated in the semi-technical dinosaur books of the time.

Tall spined vertebrae from the Early Cretaceous of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

were once considered to be very similar to those of ''Acrocanthosaurus'', and in 1988 Gregory S. Paul

Gregory Scott Paul (born December 24, 1954) is an American freelance researcher, author and illustrator who works in paleontology, and more recently has examined sociology and theology. He is best known for his work and research on theropod dino ...

named them as a second species of the genus, ''A. altispinax''. These bones were originally assigned to '' Altispinax'', an English theropod otherwise known only from teeth, and this assignment led to at least one author proposing that ''Altispinax'' itself was a synonym of ''Acrocanthosaurus''. These vertebrae were later assigned to the new genus '' Becklespinax'', separate from both ''Acrocanthosaurus'' and ''Altispinax''. It was still regarded as an Allosaurid by some researchers researches, and is still occasionally placed within that family.

Most cladistic

Cladistics (; ) is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived char ...

analyses including ''Acrocanthosaurus'' have found it to be a carcharodontosaurid, usually in a basal position relative to the Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

n ''Carcharodontosaurus'' and ''Giganotosaurus'' from South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sout ...

. It has often been considered the sister taxon to the equally basal ''Eocarcharia

''Eocarcharia'' (meaning "dawn shark") is a genus of carcharodontosaurid theropod dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous Elrhaz Formation that lived in the Sahara 112 million years ago, in what today is the country of Niger. It was discovered in 2 ...

'', also from Africa. ''Neovenator

''Neovenator'' (nee-o-ven-a-tor meaning "new hunter") is a genus of carcharodontosaurian theropod dinosaur. It is known from several skeletons found in the Early Cretaceous (Barremian~130-125 million years ago) Wessex Formation on the south coa ...

'', discovered in England, is often considered an even more basal carcharodontosaurid, or as a basal member of a sister group called Neovenatoridae

Neovenatoridae is a proposed clade of carcharodontosaurian dinosaurs uniting some primitive members of the group such as ''Neovenator'' with the Megaraptora, a group of theropods with controversial affinities. Other studies recover megaraptorans ...

. This suggests that the family originated in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

and then dispersed into the southern continents (at the time united as the supercontinent

In geology, a supercontinent is the assembly of most or all of Earth's continental blocks or cratons to form a single large landmass. However, some geologists use a different definition, "a grouping of formerly dispersed continents", which leav ...

Gondwana). If ''Acrocanthosaurus'' was a carcharodontosaurid, then dispersal would also have occurred into North America. All known carcharodontosaurids lived during the early-to-middle Cretaceous Period.

The following cladogram after Novas ''et al.'', 2013, shows the placement of ''Acrocanthosaurus'' within Carcharodontosauridae. In 2011, Oliver Rauhut named a new genus of theropod dinosaur from the Tendaguru Formation

The Tendaguru Formation, or Tendaguru Beds are a highly fossiliferous formation and Lagerstätte located in the Lindi Region of southeastern Tanzania. The formation represents the oldest sedimentary unit of the Mandawa Basin, overlying Neoproter ...

in Tanzania named '' Veterupristisaurus'' and found it to be a sister taxon to ''Acrocanthosaurus'', further supporting its position as a carcharodontosaurid.

Paleobiology

Growth and longevity

From the bone features of the

From the bone features of the holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of sever ...

OMNH 10146 and NCSM 14345, it is estimated that ''Acrocanthosaurus'' required at least 12 years to fully grow. This number may have been much higher because in the process of bones remodeling and the growth of the medullary cavity

The medullary cavity (''medulla'', innermost part) is the central cavity of bone shafts where red bone marrow and/or yellow bone marrow ( adipose tissue) is stored; hence, the medullary cavity is also known as the marrow cavity.

Located in the m ...

, some Harris lines

Growth arrest lines, also known as Harris lines, are lines of increased bone density that represent the position of the growth plate at the time of insult to the organism and formed on long bones due to growth arrest. They are only visible by radi ...

were lost. If accounting for these lines, ''Acrocanthosaurus'' needed 18–24 years to be mature.

Bite force

The bite force of ''Acrocanthosaurus'' was studied and compared with that of 33 other dinosaurs by Sakamoto ''et al.'' (2022). According to the results, its bite force at the anterior part of the jaws was 8,266 newtons, while the posterior bite force was estimated to be 16,894 newtons.Forelimb function

Like those of most other non-avian theropods, ''Acrocanthosaurus'' forelimbs did not make contact with the ground and were not used for locomotion; instead, they served a predatory function. The discovery of a complete forelimb (NCSM 14345) allowed the first analysis of the function and range of motion of the forelimb in ''Acrocanthosaurus''. The study examined the bone surfaces which would have articulated with other bones to determine how far thejoint

A joint or articulation (or articular surface) is the connection made between bones, ossicles, or other hard structures in the body which link an animal's skeletal system into a functional whole.Saladin, Ken. Anatomy & Physiology. 7th ed. McGraw- ...

s could move without dislocating. In many of the joints, the bones did not fit together exactly, indicating the presence of a considerable amount of cartilage in the joints, as is seen in many living archosaurs. Among other findings, the study suggested that, in a resting position, the forelimbs would have hung from the shoulders with the humerus angled backward slightly, the elbow bent, and the claws facing medially (inwards).

The shoulder of ''Acrocanthosaurus'' was limited in its range of motion compared to that of humans. The arm could not swing in a complete circle, but could retract (swing backward) 109 ° from the vertical, so that the humerus could actually be angled slightly upwards. Protraction

Motion, the process of movement, is described using specific anatomical terms. Motion includes movement of organs, joints, limbs, and specific sections of the body. The terminology used describes this motion according to its direction relativ ...

(swinging forward) was limited to only 24° past the vertical. The arm was unable to reach a vertical position when adducting (swinging downwards) but could abduct (swing upwards) to 9° above horizontal. Movement at the elbow was also limited compared to humans, with a total range of motion of only 57°. The arm could not completely extend (straighten), nor could it flex (bend) very far, with the humerus unable even to form a right angle with the forearm. The radius

In classical geometry, a radius ( : radii) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The name comes from the latin ''radius'', meaning ray but also the ...

and ulna

The ulna (''pl''. ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone found in the forearm that stretches from the elbow to the smallest finger, and when in anatomical position, is found on the medial side of the forearm. That is, the ulna is on the same side of t ...

(forearm bones) locked together so that there was no possibility of pronation or supination (twisting) as in human forearms.

None of the

None of the carpal

The carpal bones are the eight small bones that make up the wrist (or carpus) that connects the hand to the forearm. The term "carpus" is derived from the Latin carpus and the Greek καρπός (karpós), meaning "wrist". In human anatomy, the ...

s (wrist bones) fit together precisely, suggesting the presence of a large amount of cartilage in the wrist, which would have stiffened it. All of the digits were able to hyperextend (bend backward) until they nearly touched the wrist. When flexed, the middle digit would converge towards the first digit, while the third digit would twist inwards. The first digit of the hand bore the largest claw, which was permanently flexed so that it curved back towards the underside of the hand. Likewise, the middle claw may have been permanently flexed, while the third claw, also the smallest, was able to both flex and extend. After determining the ranges of motion in the joints of the forelimb, the study went on to hypothesize about the predatory habits of ''Acrocanthosaurus''. The forelimbs could not swing forward very far, unable even to scratch the animal's own neck. Therefore, they were not likely to have been used in the initial capture of prey and ''Acrocanthosaurus'' probably led with its mouth when hunting. On the other hand, the forelimbs were able to retract towards the body very strongly. Once prey had been seized in the jaws, the heavily muscled forelimbs may have retracted, holding the prey tightly against the body and preventing escape. As the prey animal attempted to pull away, it would only have been further impaled on the permanently flexed claws of the first two digits. The extreme hyperextensibility of the digits may have been an adaptation allowing ''Acrocanthosaurus'' to hold struggling prey without fear of dislocation. Once the prey was trapped against the body, ''Acrocanthosaurus'' may have dispatched it with its jaws. Another possibility is that ''Acrocanthosaurus'' held its prey in its jaws, while repeatedly retracting its forelimbs, tearing large gashes with its claws. Other less probable theories have suggested the forelimb range of motion being able to grasp onto the side of a sauropod and clinging on to topple the sauropods of smaller stature, though this is unlikely due to ''Acrocanthosaurus'' having a rather robust leg structure compared to other similarly structured theropods.

Brain and inner ear structure

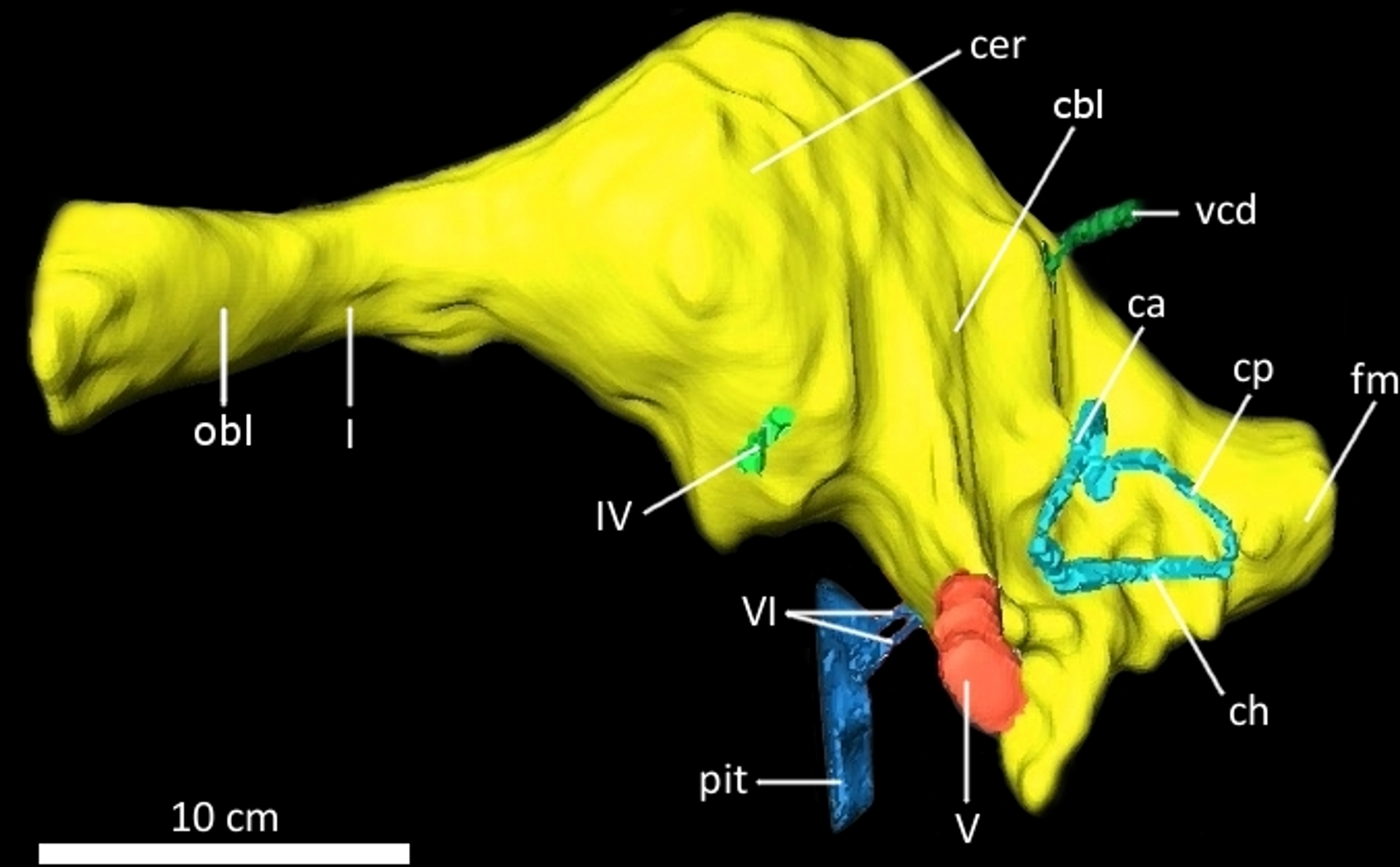

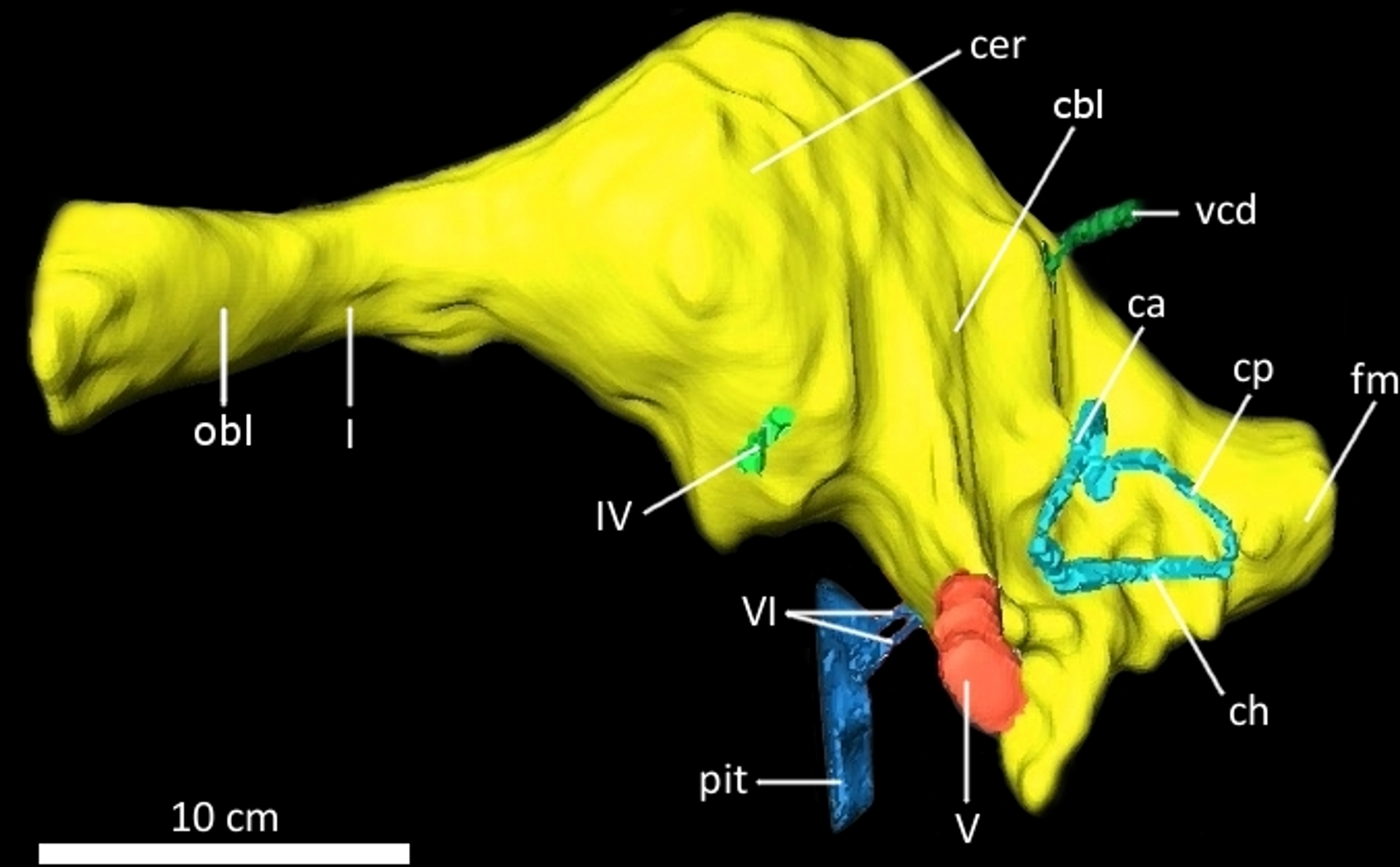

In 2005, scientists reconstructed an

In 2005, scientists reconstructed an endocast

An endocast is the internal cast of a hollow object, often referring to the cranial vault in the study of brain development in humans and other organisms. Endocasts can be artificially made for examining the properties of a hollow, inaccessible sp ...

(replica) of an ''Acrocanthosaurus'' cranial cavity using computed tomography (CT scanning) to analyze the spaces within the holotype braincase (OMNH 10146). In life, much of this space would have been filled with the meninges and cerebrospinal fluid

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a clear, colorless body fluid found within the tissue that surrounds the brain and spinal cord of all vertebrates.

CSF is produced by specialised ependymal cells in the choroid plexus of the ventricles of the ...

, in addition to the brain itself. However, the general features of the brain and cranial nerves

Cranial nerves are the nerves that emerge directly from the brain (including the brainstem), of which there are conventionally considered twelve pairs. Cranial nerves relay information between the brain and parts of the body, primarily to and f ...

could be determined from the endocast and compared to other theropods for which endocasts have been created. While the brain is similar to many theropods, it is most similar to that of allosauroids. It most resembles the brains of ''Carcharodontosaurus'' and ''Giganotosaurus'' rather than those of ''Allosaurus'' or ''Sinraptor

''Sinraptor'' is a genus of metriacanthosaurid theropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic. The name ''Sinraptor'' comes from the Latin prefix "Sino", meaning Chinese, and "raptor" meaning robber. The specific name ''dongi'' honours Dong Zhiming. ...

'', providing support for the hypothesis that ''Acrocanthosaurus'' was a carcharodontosaurid.

The brain was slightly sigmoidal (S-shaped), without much expansion of the cerebral hemisphere

The vertebrate cerebrum (brain) is formed by two cerebral hemispheres that are separated by a groove, the longitudinal fissure. The brain can thus be described as being divided into left and right cerebral hemispheres. Each of these hemispheres ...

s, more like a crocodile than a bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

. This is in keeping with the overall conservatism of non-coelurosauria

Coelurosauria (; from Greek, meaning "hollow tailed lizards") is the clade containing all theropod dinosaurs more closely related to birds than to carnosaurs.

Coelurosauria is a subgroup of theropod dinosaurs that includes compsognathids, t ...

n theropod brains. ''Acrocanthosaurus'' had large and bulbous olfactory bulb

The olfactory bulb (Latin: ''bulbus olfactorius'') is a neural structure of the vertebrate forebrain involved in olfaction, the sense of smell. It sends olfactory information to be further processed in the amygdala, the orbitofrontal cortex ( ...

s, indicating a good sense of smell

The sense of smell, or olfaction, is the special sense through which smells (or odors) are perceived. The sense of smell has many functions, including detecting desirable foods, hazards, and pheromones, and plays a role in taste.

In humans, ...

. Reconstructing the semicircular canals

The semicircular canals or semicircular ducts are three semicircular, interconnected tubes located in the innermost part of each ear, the inner ear. The three canals are the horizontal, superior and posterior semicircular canals.

Structure

The ...

of the ear, which control balance

Balance or balancing may refer to:

Common meanings

* Balance (ability) in biomechanics

* Balance (accounting)

* Balance or weighing scale

* Balance as in equality or equilibrium

Arts and entertainment Film

* ''Balance'' (1983 film), a Bulgaria ...

, shows that the head was held at a 25° angle below horizontal. This was determined by orienting the endocast so that the lateral semicircular canal

The semicircular canals or semicircular ducts are three semicircular, interconnected tubes located in the innermost part of each ear, the inner ear. The three canals are the horizontal, superior and posterior semicircular canals.

Structure

The ...

was parallel to the ground, as it usually is when an animal is in an alert posture.

Possible footprints

The

The Glen Rose Formation

The Glen Rose Formation is a shallow marine to shoreline geological formation from the lower Cretaceous period exposed over a large area from South Central to North Central Texas. The formation is most widely known for the dinosaur footprints ...

of central Texas preserves many dinosaur footprints, including large, three-toed theropod prints. The most famous of these trackway

Historic roads (historic trails in USA and Canada) are paths or routes that have historical importance due to their use over a period of time. Examples exist from prehistoric times until the early 20th century. They include ancient trackways ...

s was discovered along the Paluxy River in Dinosaur Valley State Park

Dinosaur Valley State Park is a state park near Glen Rose, Texas, United States.

History

Dinosaur Valley State Park, located just northwest of Glen Rose in Somervell County, Texas, is a scenic park set astride the Paluxy River. The land fo ...

, a section of which is now on exhibit in the American Museum of Natural History in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

, although several other sites around the state have been described in the literature. It is impossible to say what animal made the prints, since no fossil bones have been associated with the trackways. However, scientists have long considered it likely that the footprints belong to ''Acrocanthosaurus''. A 2001 study compared the Glen Rose footprints to the feet of various large theropods but could not confidently assign them to any particular genus. However, the study noted that the tracks were within the ranges of size and shape expected for ''Acrocanthosaurus''. Because the Glen Rose Formation is close to the Antlers and Twin Mountains Formations in both geographical location and geological age, and the only large theropod known from those formations is ''Acrocanthosaurus'', the study concluded that ''Acrocanthosaurus'' was most likely to have made the tracks.

The famous Glen Rose trackway on display in New York City includes theropod footprints belonging to several individuals which moved in the same direction as up to twelve sauropod dinosaurs. The theropod prints are sometimes found on top of the sauropod footprints, indicating that they were formed later. This has been put forth as evidence that a small pack of ''Acrocanthosaurus'' was stalking a herd of sauropods. While interesting and plausible, this hypothesis is difficult to prove and other explanations exist. For example, several solitary theropods may have moved through in the same direction at different times after the sauropods had passed, creating the appearance of a pack stalking its prey. The same can be said for the purported "herd" of sauropods, who also may or may not have been moving as a group. At a point where it crosses the path of one of the sauropods, one of the theropod trackways is missing a footprint, which has been cited as evidence of an attack. However, other scientists doubt the validity of this interpretation because the sauropod did not change gait, as would be expected if a large predator were hanging onto its side.

Pathology

The skull of the ''Acrocanthosaurus atokensis''

The skull of the ''Acrocanthosaurus atokensis'' holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of sever ...

shows light exostotic material on the squamosal The squamosal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians, and birds. In fishes, it is also called the pterotic bone.

In most tetrapods, the squamosal and quadratojugal bones form the cheek series of the skull. The bone forms an ancestral co ...

. The neural spine

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates,Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristic ...

of the eleventh vertebra was fractured and healed while the neural spine

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates,Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristic ...

of its third tail vertebra had an unusual hook-like structure.Molnar, R. E., 2001, Theropod paleopathology: a literature survey: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, p. 337–363.

Paleoecology

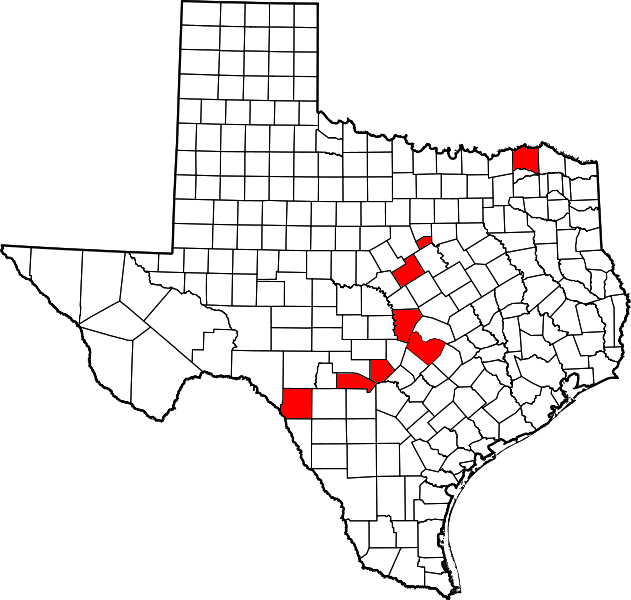

Definite ''Acrocanthosaurus'' fossils have been found in the

Definite ''Acrocanthosaurus'' fossils have been found in the Twin Mountains Formation

The Twin Mountains Formation, also known as the Twin Mak Formation, is a sedimentary rock formation, within the Trinity Group, found in Texas of the United States of America. It is a terrestrial formation of Aptian age (Lower Cretaceous), and ...

of northern Texas, the Antlers Formation

The Antlers Formation is a stratum which ranges from Arkansas through southern Oklahoma into northeastern Texas. The stratum is thick consisting of silty to sandy mudstone and fine to coarse grained sandstone that is poorly to moderately sorted. ...

of southern Oklahoma, and the Cloverly Formation

The Cloverly Formation is a geological formation of Early and Late Cretaceous age (Valanginian to Cenomanian stage) that is present in parts of Montana, Wyoming, Colorado and Utah in the western United States. It was named for a post office on th ...

of north-central Wyoming and possibly even the Arundel Formation

The Arundel Formation, also known as the Arundel Clay, is a clay-rich sedimentary rock formation, within the Potomac Group, found in Maryland of the United States of America. It is of Aptian age (Lower Cretaceous). This rock unit had been econ ...

in Maryland. These geological formation

A geological formation, or simply formation, is a body of rock having a consistent set of physical characteristics ( lithology) that distinguishes it from adjacent bodies of rock, and which occupies a particular position in the layers of rock exp ...

s have not been dated radiometrically, but scientists have used biostratigraphy

Biostratigraphy is the branch of stratigraphy which focuses on correlating and assigning relative ages of rock strata by using the fossil assemblages contained within them.Hine, Robert. “Biostratigraphy.” ''Oxford Reference: Dictionary of B ...

to estimate their age. Based on changes in ammonite taxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular nam ...

, the boundary between the Aptian and Albian

The Albian is both an age of the geologic timescale and a stage in the stratigraphic column. It is the youngest or uppermost subdivision of the Early/Lower Cretaceous Epoch/ Series. Its approximate time range is 113.0 ± 1.0 Ma to 100.5 ± 0 ...

stages

Stage or stages may refer to:

Acting

* Stage (theatre), a space for the performance of theatrical productions

* Theatre, a branch of the performing arts, often referred to as "the stage"

* ''The Stage'', a weekly British theatre newspaper

* S ...

of the Early Cretaceous has been located within the Glen Rose Formation of Texas, which may contain ''Acrocanthosaurus'' footprints and lies just above the Twin Mountains Formation. This indicates that the Twin Mountains Formation lies entirely within the Aptian stage, which lasted from 125 to 112 million years ago. The Antlers Formation contains fossils of ''Deinonychus

''Deinonychus'' ( ; ) is a genus of dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaur with one described species, ''Deinonychus antirrhopus''. This species, which could grow up to long, lived during the early Cretaceous Period, about 115–108 million y ...

'' and ''Tenontosaurus

''Tenontosaurus'' ( ; ) is a genus of medium- to large-sized ornithopod dinosaur. It was a relatively medium sized ornithopod, reaching in length and in body mass. It had an unusually long, broad tail, which like its back was stiffened with a n ...

'', two dinosaur genera also found in the Cloverly Formation, which has been radiometrically dated to the Aptian and Albian stages, suggesting a similar age for the Antlers. Therefore, ''Acrocanthosaurus'' most likely existed between 125 and 100 million years ago.

During this time, the area preserved in the Twin Mountains and Antlers formations was a large floodplain

A floodplain or flood plain or bottomlands is an area of land adjacent to a river which stretches from the banks of its channel to the base of the enclosing valley walls, and which experiences flooding during periods of high discharge.Goudi ...

that drained into a shallow inland sea. A few million years later, this sea would expand to the north, becoming the Western Interior Seaway

The Western Interior Seaway (also called the Cretaceous Seaway, the Niobraran Sea, the North American Inland Sea, and the Western Interior Sea) was a large inland sea that split the continent of North America into two landmasses. The ancient sea ...

and dividing North America in two for nearly the entire Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''creta'', ...

. The Glen Rose Formation represents a coastal environment, with possible ''Acrocanthosaurus'' tracks preserved in mudflats along the ancient shoreline. As ''Acrocanthosaurus'' was a large predator, it is expected that it had an extensive home range and lived in many different environments in the area. Potential prey animals include sauropods like ''Astrodon

''Astrodon'' (aster: star, odon: tooth) is a genus of large herbivorous sauropod dinosaur, measuring in length, in height and in body mass. It lived in what is now the eastern United States during the Early Cretaceous period, and fossils have ...

'' ublished online/ref> or possibly even the enormous ''Sauroposeidon

''Sauroposeidon'' ( ; meaning "lizard earthquake god", after the Greek god Poseidon) is a genus of sauropod dinosaur known from several incomplete specimens including a bone bed and fossilized trackways that have been found in the U.S. states of ...

'', as well as large ''ornithopods

Ornithopoda () is a clade of ornithischian dinosaurs, called ornithopods (), that started out as small, bipedal running grazers and grew in size and numbers until they became one of the most successful groups of herbivores in the Cretaceous world ...

'' like ''Tenontosaurus

''Tenontosaurus'' ( ; ) is a genus of medium- to large-sized ornithopod dinosaur. It was a relatively medium sized ornithopod, reaching in length and in body mass. It had an unusually long, broad tail, which like its back was stiffened with a n ...

''. The smaller theropod ''Deinonychus

''Deinonychus'' ( ; ) is a genus of dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaur with one described species, ''Deinonychus antirrhopus''. This species, which could grow up to long, lived during the early Cretaceous Period, about 115–108 million y ...

'' also prowled the area but at in length, most likely provided only minimal competition, or even food, for ''Acrocanthosaurus''.

References

{{Taxonbar, from=Q131021 Carcharodontosaurids Albian life Aptian life Early Cretaceous dinosaurs of North America Fossil trackways Cloverly fauna Paleontology in Maryland Paleontology in Oklahoma Paleontology in Wyoming Paleontology in Texas Fossil taxa described in 1950 Taxa named by J. Willis Stovall Taxa named by Wann Langston Jr. Articles containing video clips Apex predators