Abraham Nahum Stencl on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

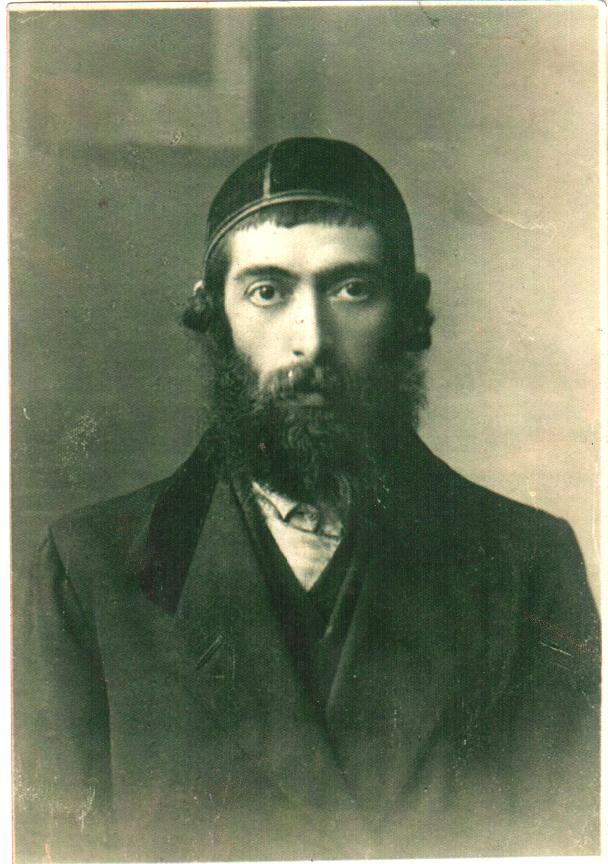

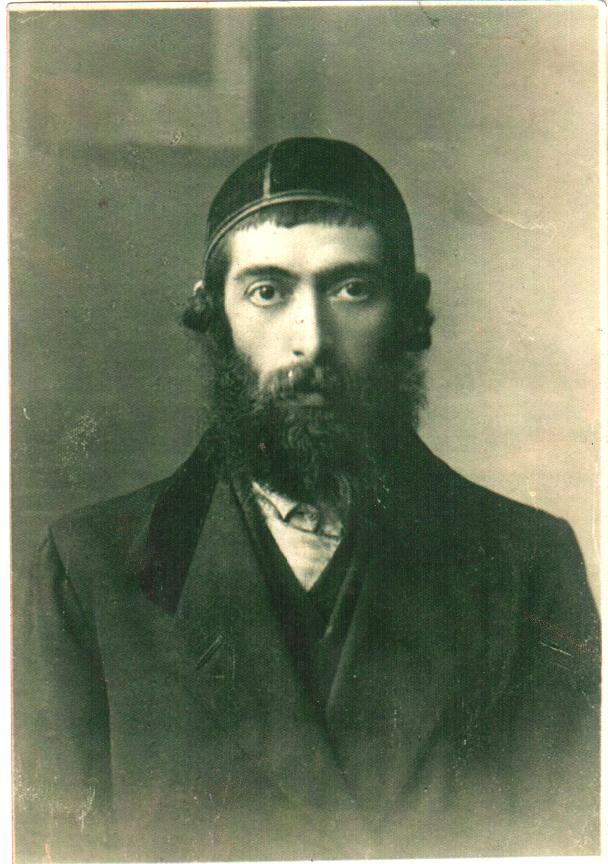

Abraham Nahum Stencl (Polish: Avrom Nokhem Sztencl, he, אברהם נחום שטנצל) (1897-1983) was a Polish-born

He began travelling to Germany, and emigrated to

He began travelling to Germany, and emigrated to  Stencl began to write

Stencl began to write

Fischerdorf

' (Fishing Village), German tr.

SOAS Special Collections

Digitised items from the collection are availabl

online

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stencl, Abraham Nahum 1897 births 1983 deaths People from Czeladź Writers from Berlin 19th-century Polish Jews Polish poets 20th-century German poets Jewish emigrants from Nazi Germany to the United Kingdom 20th-century English poets Yiddish-language poets English male poets German male poets 20th-century German male writers 20th-century English male writers

Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ver ...

poet.

Life

Stencl was born inCzeladź

Czeladź (; yi, טשעלאַדזש, Chelodz) is a town in Zagłębie Dąbrowskie (part of historic Lesser Poland), in southern Poland, near Katowice and Sosnowiec. Located in the Silesian Highlands, on the Brynica river (tributary of the Vistul ...

in south-western Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

, and studied at the yeshiva

A yeshiva (; he, ישיבה, , sitting; pl. , or ) is a traditional Jewish educational institution focused on the study of Rabbinic literature, primarily the Talmud and halacha (Jewish law), while Torah and Jewish philosophy are s ...

in Sosnowiec

Sosnowiec is an industrial city county in the Dąbrowa Basin of southern Poland, in the Silesian Voivodeship, which is also part of the Silesian Metropolis municipal association.—— Located in the eastern part of the Upper Silesian Industria ...

, where his brother, Shlomo Sztencl

Shlomo Sztencl ( he, שלמה שטנצל, pronounced ''Shtentzel'') (1884 – 1919) was a Polish Orthodox Jewish rabbi. He served as Chief Rabbi of Czeladź, Poland and Rav, '' dayan'', and rosh yeshiva of Sosnowiec, Poland. He is the author of ...

, was rabbi.Leftwich p. 665.

He left home in 1917; he joined a Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

community, the HeHalutz

HeHalutz or HeChalutz ( he, הֶחָלוּץ, lit. "The Pioneer") was a Jewish youth movement that trained young people for agricultural settlement in the Land of Israel. It became an umbrella organization of the pioneering Zionist youth moveme ...

Group. His views were not in fact Zionist, but the agricultural work appealed. Late in 1918 he received conscription papers for the Russian Army, and with his father's approval he immediately left Poland. In 1919 he travelled to the Netherlands and worked in the steel industry.

He began travelling to Germany, and emigrated to

He began travelling to Germany, and emigrated to Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

in 1921 where he met intellectuals and writers such as Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka (3 July 1883 – 3 June 1924) was a German-speaking Bohemian novelist and short-story writer, widely regarded as one of the major figures of 20th-century literature. His work fuses elements of realism and the fantastic. It ...

and Kafka's lover Dora Diamant

Dora Diamant (Dwojra Diament, also Dymant) (4 March 1898 – 15 August 1952) is best remembered as the lover of the writer Franz Kafka and the person who kept some of his last writings in her possession until they were confiscated by the Gest ...

. A religious Jew by upbringing, he now led an extreme and spontaneous bohemian life, and became an ''habitué'' of the Romanisches Café

The ''Romanisches Café'' ("Romanesque Café") was a café- bar in Berlin well known as a meeting place for artists. It was located in what is now Breitscheidplatz at the end of the Kurfürstendamm in the Charlottenburg district (although that ...

.

Stencl began to write

Stencl began to write Yiddish poetry

Yiddish literature encompasses all those belles-lettres written in Yiddish, the language of Ashkenazic Jewry which is related to Middle High German. The history of Yiddish, with its roots in central Europe and locus for centuries in Eastern Euro ...

in a pioneer modernist

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

and expressionist

Expressionism is a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Northern Europe around the beginning of the 20th century. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it rad ...

style, publishing poems from 1925 and several books into the 1930s. His poems were translated into German, and were well reviewed by Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novella ...

and Arnold Zweig

Arnold Zweig (10 November 1887 – 26 November 1968) was a German writer, pacifist and socialist.

He is best known for his six-part cycle on World War I.

Life and work

Zweig was born in Glogau, Prussian Silesia (now Głogów, Poland), the son ...

. He ran a secretive Polish-Yiddish literary group, and kept in touch with Diamant, until she left in February 1936.

Stencl was arrested in 1936 and tortured by the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

. However, he was released and made his escape to the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, settling in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

(from 1944), initially in Hampstead

Hampstead () is an area in London, which lies northwest of Charing Cross, and extends from Watling Street, the A5 road (Roman Watling Street) to Hampstead Heath, a large, hilly expanse of parkland. The area forms the northwest part of the Lon ...

, but soon moving to Whitechapel

Whitechapel is a district in East London and the future administrative centre of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is a part of the East End of London, east of Charing Cross. Part of the historic county of Middlesex, the area formed ...

. There he met again with Dora Diamant, and founded the ''Literarische Shabbes Nokhmitogs'' (later known as ''Friends of Yiddish''), a weekly meeting involving political debate, literature, poetry and song, in the Yiddish language

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ver ...

. He found an English translator in Joseph Leftwich

Joseph Leftwich (Zutphen September 28 1892 – Islington February 28 1983), born Joseph Lefkowitz, was a British critic and translator into English of Yiddish literature.Schwartz, Richard H. (2001). ''Judaism and Vegetarianism''. p. 175. Lantern ...

. He also edited the Yiddish literary journal ''Loshn und Lebn'', from 1946 to 1981. Diamant in 1951 defined Stencl's work as a ''mitzvah

In its primary meaning, the Hebrew word (; he, מִצְוָה, ''mīṣvā'' , plural ''mīṣvōt'' ; "commandment") refers to a commandment commanded by God to be performed as a religious duty. Jewish law () in large part consists of discus ...

'', to keep Yiddish alive.Diamant, p. 297.

When Stencl died in 1983, his great-niece donated his papers to the School of Oriental and African Studies

SOAS University of London (; the School of Oriental and African Studies) is a public research university in London, England, and a member institution of the federal University of London. Founded in 1916, SOAS is located in the Bloomsbury ar ...

.

Works

*''Un du bist Got'' (c. 1924, Leipzig) as A. N. Sztencl * Stencl, A. N.,Fischerdorf

' (Fishing Village), German tr.

Etta Federn

Etta Federn-Kohlhaas (April 28, 1883 – May 9, 1951) or Marietta Federn, also published as Etta Federn-Kirmsse and Esperanza, was a writer, translator, educator and important woman of letters in pre-war Germany. In the 1920s and 1930s, she was ac ...

, Berlin-Wilmersdorf: Kartell Lyrische Autoren, 1931.

*Stencl, Abraham Nahum, ''Londoner soneṭn'', Y. Naroditsḳi, 1937.

*Stencl, Abraham Nahum, ''Englishe maysṭer in der moleray : tsu der oysshṭelung itsṭ fun zeyere bilder in der arṭ-galerye in Ṿayṭshepl'', Y. Naroditsḳi, 1942.

*Stencl, Abraham Nahum, ''All My Young Years : Yiddish Poetry from Weimar Germany'', bilingual edition (Yiddish - English), tr. Haike Beruriah Wiegand & Stephen Watts, intro. Heather Valencia, Nottingham : Five Leaves, 2007.

*An English translation of one of Stencl's poems, ''Where Whitechapel Stood'' is published in Sinclair's ''London: City of Disappearances'', referenced below.

Notes

Sources

*. * * *Kathi Diamant (2003), ''Kafka's Last Love: The Mystery of Dora Diamant''. *The papers of Abrahman Nahum Stencl are held bSOAS Special Collections

Digitised items from the collection are availabl

online

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stencl, Abraham Nahum 1897 births 1983 deaths People from Czeladź Writers from Berlin 19th-century Polish Jews Polish poets 20th-century German poets Jewish emigrants from Nazi Germany to the United Kingdom 20th-century English poets Yiddish-language poets English male poets German male poets 20th-century German male writers 20th-century English male writers