Abdulrauf Fitrat on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Abdurauf Fitrat (sometimes spelled Abdulrauf Fitrat or Abdurrauf Fitrat, uz, Abdurauf Fitrat / Абдурауф Фитрат; 1886 – 4 October 1938) was an Uzbek author, journalist and politician in

Fitrat was born in 1886 (he himself stated 1884Allworth 2000, p. 7) in Bukhara. Little is known about his childhood, which is, according to

Fitrat was born in 1886 (he himself stated 1884Allworth 2000, p. 7) in Bukhara. Little is known about his childhood, which is, according to

In September 1920, the Emir of Bukhara was overthrown by the Young Bukharans and the

In September 1920, the Emir of Bukhara was overthrown by the Young Bukharans and the

After Bukhara had lost its independence and changed side from nationalism and Muslim reformism to secular

After Bukhara had lost its independence and changed side from nationalism and Muslim reformism to secular

Fitrat was suspected to be a member of a

Fitrat was suspected to be a member of a

''International Journal of Central Asian Studies''; Volume 5

(PDF; 179 kB). The International Association of Central Asian Studies, 2000. due to the activity of the critic Izzat Sulton and his achievements in the areas of literature and education now recognized, the Soviet press continued criticizing him for his liberal and the Tajiks for his Turkophile tendencies. Almost all his works remained banned until perestroika. However, some copies of Fitrat's dramas were preserved in academic libraries. For a long time, Fitrat was remembered as an Uzbek or Turkish nationalist.Bert G. Fragner: ''Traces of Modernisation and Westernisation? Some Comparative Considerations concerning Late Bukhāran Chronicles''. In: Hermann Landolt, Todd Lawson: ''Reason and Inspiration in Islam: Theology, Philosophy and Mysticism in Muslim Thought. Essays in Honour of Hermann Landolt'' (p. 542–565), New York 2005; p. 555 While his prose started being recognized by Uzbek scholars of literature in the 1960s and '70s and several stories were once again published, explicitly negative comments were still in circulation up to the '80s. Even in the '90s sources on Fitrat in Uzbekistan were still scarce. Only after 1989 several works of Fitrat were printed in Soviet magazines and newspapers. According to Halim Kara's studies three historical periods of Fitrat's rehabilitation can be distinguished in Uzbekistan: In the course of de-Stalinization the then First Secretary of the Uzbek Central Committee of the

Until 1929, the alphabets of the Central Asian Turkic languages were Latinized. Fitrat was a member of the ''Committee for the new Latin alphabet in Uzbekistan'' and had significant impact on the latinization of Tajik, whose Latin script he wanted to harmonize as much as possible with the Uzbek one.

Until 1929, the alphabets of the Central Asian Turkic languages were Latinized. Fitrat was a member of the ''Committee for the new Latin alphabet in Uzbekistan'' and had significant impact on the latinization of Tajik, whose Latin script he wanted to harmonize as much as possible with the Uzbek one.

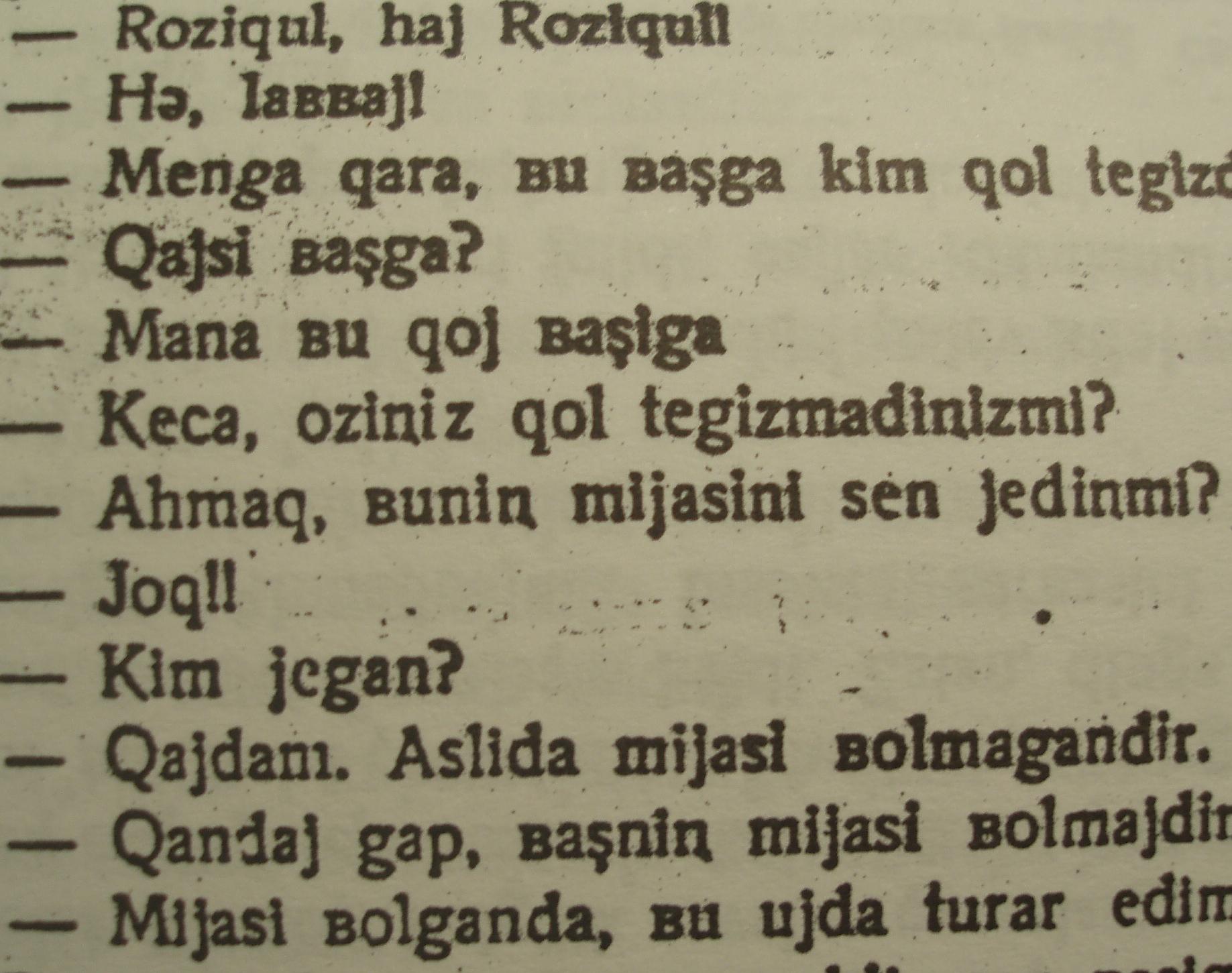

Like Abdulla Qodiriy and Gʻafur Gʻulom, Fitrat increasingly used satiric concepts in his stories from the 1920s onwards. Only a few years earlier, prose had started gaining ground in Central Asia; by including satirical elements, reformers like Fitrat succeeded in winning over the audience. These short stories were used in alphabetization campaigns, where traditional characters and mindsets were presented in a new, socially and politically relevant context. In order to stay similar to the structure of traditional

Like Abdulla Qodiriy and Gʻafur Gʻulom, Fitrat increasingly used satiric concepts in his stories from the 1920s onwards. Only a few years earlier, prose had started gaining ground in Central Asia; by including satirical elements, reformers like Fitrat succeeded in winning over the audience. These short stories were used in alphabetization campaigns, where traditional characters and mindsets were presented in a new, socially and politically relevant context. In order to stay similar to the structure of traditional

''Feṭrat, ʿAbd-al-Raʾūf Boḵārī''

In: ''

Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

under Russian and Soviet rule.

Fitrat made major contributions to modern Uzbek literature with both lyric and prose in Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

, Turki

Chagatai (چغتای, ''Čaġatāy''), also known as ''Turki'', Eastern Turkic, or Chagatai Turkic (''Čaġatāy türkīsi''), is an extinct Turkic literary language that was once widely spoken across Central Asia and remained the shared literar ...

, and late Chagatai. Beside his work as a politician and scholar in many fields, Fitrat also authored poetic and dramatic literary texts. Fitrat initially composed poems in the Persian language, but switched to a puristic Turkic tongue by 1917. Fitrat was responsible for the change to Uzbek as Bukhara's national language in 1921, before returning to writing texts in Tajik later during the 1920s. In the late 1920s, Fitrat took part in the efforts for Latinization of Uzbek and Tajik.

Fitrat was influenced by his studies in Istanbul during the early 1910s, where he came into contact with Islamic reformism. After returning to Central Asia, he turned into an influential ideological leader of the local jadid movement. In opposition to and in exile from the Bukharan emir he sided with the communists. After the end of the emirate, Fitrat accepted several posts in the government of the Bukharan People's Soviet Republic, before he was forced to spend a year in Russia. Later, he taught at several colleges and universities in the then Uzbek SSR.

During Stalin's Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secret ...

, Fitrat was arrested and prosecuted for counter-revolutionary and nationalist activities, and finally executed in 1938. After his death, his work was banned for decades. Fitrat was rehabilitated in 1956, yet critical evaluation of his work has changed several times since. While there are Tajik criticis that call the likes of Fitrat "traitors", other writers have given him the title of a martyr (''shahid

''Shaheed'' ( , , ; pa, ਸ਼ਹੀਦ) denotes a martyr in Islam. The word is used frequently in the Quran in the generic sense of "witness" but only once in the sense of "martyr" (i.e. one who dies for his faith); ...

''), particularly in independent Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan (, ; uz, Ozbekiston, italic=yes / , ; russian: Узбекистан), officially the Republic of Uzbekistan ( uz, Ozbekiston Respublikasi, italic=yes / ; russian: Республика Узбекистан), is a doubly landlocked co ...

.

Naming variants

Fitrat's name has a number of variation across forms and transliterations: He mostly went by the pen name ''Fitrat'' ( ''Fiṭrat'', also transcribed as ''Fetrat'' or, according to the Uzbek spelling reform of 1921, ''Pitrat''). This name, derived from theArabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

term '', fiṭra'', meaning “nature, creation”, in Ottoman Turkish stood for the concept of nature and true religion. In Central Asia, however, according to the Russian turkologist Lazar Budagov

Lazar may refer to:

* Lazar (name), any of various persons with this name

* Lazar BVT, Serbian mine resistant, ambush-protected, armoured vehicle

* Lazar 2, Serbian armored vehicle

* Lazar 3, Serbian armored van

* Lazăr, a tributary of the river ...

, the same word was used to refer to alms given during Eid al-Fitr. In Persian and Tajik the notion of ''fitrat'' includes religion, creation and wisdom. ''Fitrat'' was used as a pen name before by the poet Fitrat Zarduz Samarqandi Fitrat may refer to:

* ''Fitrat'' (TV series), Pakistani romantic drama television series

People

* Abdul Qadir Fitrat, Afghan banker

*Abdurauf Fitrat

Abdurauf Fitrat (sometimes spelled Abdulrauf Fitrat or Abdurrauf Fitrat, uz, Abdurauf Fitrat ...

(late 17th to early 18th centuries). Abdurauf Fitrat's first known pseudonym was ''Mijmar'' (taken from the Arabic , ''miǧmar'', “incensory”).Allworth 2002, p. 359.

Fitrat's Arabic name is ''ʿAbd ar-Raʾūf b. ʿAbd ar-Raḥīm'' (sometimes rendered ), with ''Abdurauf'' as his proper name. At times, the nisba

The Arabic language, Arabic word nisba (; also transcribed as ''nisbah'' or ''nisbat'') may refer to:

* Arabic nouns and adjectives#Nisba, Nisba, a suffix used to form adjectives in Arabic grammar, or the adjective resulting from this formation

**c ...

''Bukhārāī'' was used. In reformed Arabic script, ''Fitrat'' was depicted as or . The Turkic variant of the nasab

Arabic language names have historically been based on a long naming system. Many people from the Arabic-speaking and also Muslim countries have not had given/ middle/ family names but rather a chain of names. This system remains in use throughou ...

is .

Some of the many Russian variants of his name are ''Abdurauf Abdurakhim ogly Fitrat'' and ''Abd-ur-Rauf''; Fitrats Soviet, russified name is ''Abdurauf Abdurakhimow'' or, omitting the component '' Abd'', ''Rauf Rakhimovich Fitrat''. The variant ''Fitratov'' can also be found. In Uzbek- Cyrillic script his name is to be depicted with ; his modern Tajik name is ''Abdurraufi Fitrat''.

Fitrat sometimes bore the titles of "hajji

Hajji ( ar, الحجّي; sometimes spelled Hadji, Haji, Alhaji, Al-Hadj, Al-Haj or El-Hajj) is an honorific title which is given to a Muslim who has successfully completed the Hajj to Mecca. It is also often used to refer to an elder, since i ...

" and "professor". His first name can be found as ''Abdurrauf'', ''Abdulrauf'' or ''Abdalrauf'' in Latin transliterations. Fitrat occasionally signed his works only using his first name or he sh

Life and Work

Education in Bukhara

Fitrat was born in 1886 (he himself stated 1884Allworth 2000, p. 7) in Bukhara. Little is known about his childhood, which is, according to

Fitrat was born in 1886 (he himself stated 1884Allworth 2000, p. 7) in Bukhara. Little is known about his childhood, which is, according to Adeeb Khalid

Adeeb Khalid (born February 17, 1964) is associate professor and Jane and Raphael Bernstein Professor of Asian Studies and History in the history department of Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota. His academic contributions are highly cited ...

, characteristic for Central Asian figures of this era. His father Abdurahimboy

A boy is a young male human. The term is commonly used for a child or an adolescent. When a male human reaches adulthood, he is described as a man.

Definition, etymology, and use

According to the ''Merriam-Webster Dictionary'', a boy is ...

was a devout Muslim and a trader,Rustam Shukurov, Muḣammadjon Shukurov, Edward A. Allworth (ed.); Sharif Jan Makhdum Sadr Ziyaʼ: ''The personal history of a Bukharan intellectual: the diary of Muḥammad-Sharīf-i Ṣadr-i Ẕiya''. Brill; Leiden 2004; p. 323 who would leave the family in the direction of Margilan

Margilan ( uz, Marg‘ilon/Марғилон, ; russian: Маргилан) is a city (2022 pop. 242,500) in Fergana Region in eastern Uzbekistan. Administratively, Margilan is a district-level city, that includes the urban-type settlement Yangi Marg ...

and later Kashgar.Allworth 2000, p. 6 Fitrat came by most of his worldly education through his broadly read mother, named Mustafbibi, Nastarbibi or Bibijon according to varied sources. According to Edward A. Allworth

Edward A. Allworth (December 1, 1920 – October 20, 2016) was an American historian specializing in Central Asia. Allwarth was widely regarded as the West’s leading scholar on Central Asian studies. He extensively studied the various et ...

she brought him into contact with the works of Bedil, Fuzûlî, Ali-Shir Nava'i and others.Allworth 2000, p. 6f Abdurauf grew up with a brother (Abdurahmon) and a sister (Mahbuba).

Muhammadjon Shakuri Muhammadjon Shakuri ( tg, Муҳаммадҷон Шакурӣ, fa, محمدجان شکوری; February 1925, in Bukhara – September 16, 2012, in Dushanbe), also known as Muhammad Sharifovich Shukurov, was a prominent Tajik intellectual and one o ...

suggests that Firat completed the hajj together with his father during his childhood. After receiving education at a maktab-type school Fitrat is said to have begone studies at the Mir-i Arab Madrasah of Bukhara in 1899 and to have completed them in 1910. As SHakuri continues, Fitrat travelled extensively through Russian Turkestan

Russian Turkestan (russian: Русский Туркестан, Russkiy Turkestan) was the western part of Turkestan within the Russian Empire’s Central Asian territories, and was administered as a Krai or Governor-Generalship. It comprised the ...

and the Emirate of Bukhara between 1907 and 1910. The philologist Begali Qosimov thinks that Fitrat studied in Bukhara until he was 18 and that he completed the hajj between 1904 and 1907, also visiting Turkey, Iran, India and Russia. According to Zaynobiddin Abdurashidov, prorector at the Alisher Navoiy University for Uzbek language and literature, it was in the beginning of the 20th century that Fitrat went on a pilgrimage through Asia to Mecca during which he spent some time in India, where he earned some money for the journey home as a barber. As per Abdurashidov, Fitrat was already known as a poet then, using the pen name ''Mijmar''. Beside Shakuri, also Khalid and AllworthAllworth 2002, p. 357 mention the Mir-i Arab Madrasah as Fitrat's place of study in Bukhara. While studying at the madrasah Fitrat was also instructed in ancient Greek philosophy by his teacher.

In his autobiography, published in 1929, Fitrat wrote that Bukhara had been one of the darkest religious centres. He had been a devout Muslim and initially in opposition to the reform movement of the Jadids (''usul-i jadid'' ‚new method‘). Fitrat himself never received basic education in that "new method". According to Sadriddin Aini

Sadriddin Ayni ( tg, Садриддин Айнӣ, fa, صدرالدين عينى, russian: Садриддин Саидмуродович Саидмуродов; 15 April 1878 – 15 July 1954) was a Tajik intellectual who wrote poetry, fiction, ...

Fitrat was known as one of the most enlightened and commendable students of the time in Bukhara,Sarfraz Khan: ''Muslim Reformist Political Thought. Revivalists, Modernists and Free Will''. Routledge, London/New York 2003, ISBN 978-1-136-76959-7; p. 118f whilst being effectively unknown outside the city until 1911. Abdurashidov's explanation of why Fitrat did not take part in the activities of the first group of jadids in Bukhara refers to the strict, anti-liberal regime under emir 'Abd al-Ahad Khan. Abdurashidov continues that Fitrat became interested in reformist ideas approximately in 1909 and suggests that this happened under the influence of the magazine ''Sırat-ı Müstakim'' by Mehmet Âkif Ersoy. Together with other magazines and newspapers, this magazine circulated among Bukhara's students during this time. Beyond that, Mahmudkhodja Behbudiy

Mahkmudkhodja Behbudiy ( Cyrillic Маҳмудхўжа Беҳбудий; Arabic script ; born as Mahmudkhodja ibn Behbud Chodscha) (* 20 January 1875 in Samarkand; † 25 March 1919 in Qarshi) was a Jadid activist, writer, journalist and leadin ...

was a mentor to Fitrat.Borjian 1999, p. 564–567 After completing his education Fitrat taught at a madrasah for a short period.

Stay in Istanbul and Jadid leader

Around 1909, jadid actors in Bukhara andIstanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

(Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

) built an organizational infrastructure in order to enable Bukharan students and teachers to study in the capital of the Ottoman empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. According to reports, Fitrat himself was involved in these activities. Thanks to a grant given by the secret "society for the education of the children" ''(Tarbiyayi atfol)'' which was financed by merchantsKhalid 1998, p. 111 Fitrat himself was able to go to Istanbul. He arrived there in spring of 1910 shortly after the very first group. "Sometimes", says Sarfraz Khan from the University of Peshawar

The University of Peshawar ( ps, د پېښور پوهنتون; hnd, پشور یونیورسٹی; ur, ; abbreviated UoP; known more popularly as Peshawar University) is a public research university located in Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pa ...

, Fitrat's departure to Turkey is described as an effort to flee from the persecution by the authorities after a conflict between Shia and Sunni Muslims in Bukhara in January 1910. Other authors date Fitrat's leaving to the year 1909.Sharifa Tosheva: ''The Pilgrimage Books of Central Asia. Routes and Impressions (19th and early 20th centuries)''. In: Alexandre Papas, Thierry Zarcone, Thomas Welsford (ed.): ''Central Asian Pilgrims. Hajj Routes and Pious Visits between Central Asia and the Hijaz'' (S. 234–249). Klaus Schwarz Verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-220882-3 ''(Islamkundliche Untersuchungen; vol. 308)''; p. 246

During Fitrat's stay, in the Second Constitutional Era

The Second Constitutional Era ( ota, ایكنجی مشروطیت دورى; tr, İkinci Meşrutiyet Devri) was the period of restored parliamentary rule in the Ottoman Empire between the 1908 Young Turk Revolution and the 1920 dissolution of the ...

, Istanbul was governed by the Young Turks. These historical circumstances influenced Fitrat, the activities and the general social surroundings of the Bukharan students in Istanbul heavily.Kamoludin Abdullaev: ''Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan''. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham/London 2018, ISBN 978-1-5381-0251-0; p. 153Zaynabidin Abdirashidov: ''Known and Unknown Fiṭrat. Early Convictions and Activities''. In: ''Acta Slavica Iaponica'', vol. 37 (p. 103–118), 2016. p. 111 What Fitrat did after his arrival in Istanbul is not known exactly. According to Abdurashidov's analysis, Fitrat was integrated in the Bukharan diasporic community (he often gets mentioned as one of the founders of the benevolent society ''Buxoro ta’mimi maorif''), he worked as a vendor at a bazaar, as a street cleaner, and as an assistant cook. Apart from that, he prepared for the entry exams at a madrasah, which he – according to Abdirashidov – probably passed mid-1913. This allowed him to become one of the first students of the Vaizin madrasah, which was founded in December 1912 and which used the "new method". Here he did not only receive lessons in Islamic science, but also in Oriental literature.

Other authors state that Fitrat spent the years between 1909 and 1913 studying at the ''Darülmuallimin'', a training institute for teachers, or at the University of Istanbul

, image = Istanbul_University_logo.svg

, image_size = 200px

, latin_name = Universitas Istanbulensis

, motto = tr, Tarihten Geleceğe Bilim Köprüsü

, mottoeng = Science Bridge from Past to the Future

, established = 1453 1846 1933

...

. During his stay Fitrat became acquainted with further Middle Eastern reform movements, got into contact with the Pan-Turanist movement and with emigrants from the Tsardom of Russia, and turned into the leader of the jadids in Istanbul.Khalid 2015, p. 40 He wrote several works in which he – always in Persian language

Persian (), also known by its endonym Farsi (, ', ), is a Western Iranian language belonging to the Iranian branch of the Indo-Iranian subdivision of the Indo-European languages. Persian is a pluricentric language predominantly spoken a ...

– demanded reforms in the social and cultural life of Central Asia and a will to progress.Khalid 1998, p. 108. His first texts were published in the Islamist newspapers ''Hikmet'', published by Şehbenderzâde Filibeli Ahmed Hilmi, and ''Sırat-ı Müstakim'', furthermore in Behbudiys ''Oyina'' and the Turkist Türk Yurdu

''Türk Yurdu'' is a monthly Turkish magazine that was first published on the 30 November 1911. It was an important magazine propagating Pan-Turkism. It was founded by Yusuf Akçura, Ahmet Ağaoğlu, Ali Hüseynzade. Ziya Gökalp said: "all Tu ...

. In his texts Fitrat pushed for the unity of all Muslims and portrayed Istanbul with the Ottoman sultan as the center of the Muslim world.

Two of the three books Fitrat published during his stay in Istanbul, the "Debate between a Teacher from Bukhara and a European" (''Munozara'', 1911) and the "Tales of an Indian Traveller" ''(Bayonoti sayyohi hindi)'', achieved great popularity in Central Asia ''Munozara'' was translated into Turkestani Turkish by Haji Muin from Samarkand in 1911. It was published in the Tsarist newspaper ''Turkiston viloyatining gazeti'' and later as a book.Kleinmichel 1993, p. 30 While the Persian version did not, a Turkish version circulated in Bukhara as well. The latter version was expanded by a foreword by Behbudiy. Behbudiy also translated ''Bayonoti sayyohi hindi'' into Russian, and he convinced Fitrat to expand ''Munozara'' by a plea to learn Russian.

The outbreak of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

rendered Fitrat's completion of his studies in Istanbul impossible and forced him, like many other Bukharan students, to return to Transoxania

Transoxiana or Transoxania (Land beyond the Oxus) is the Latin name for a region and civilization located in lower Central Asia roughly corresponding to modern-day eastern Uzbekistan, western Tajikistan, parts of southern Kazakhstan, parts of ...

prematurely.

The final years of an emirate

After his return to Bukhara Fitrat took an active role in the movement for reforms, especially in the fight for "new method" schools, and turned into the leader of the left wing of the local jadid movement.Sarfraz Khan: ''Muslim Reformist Political Thought. Revivalists, Modernists and Free Will''. Routledge, London/New York 2003, ISBN 978-1-136-76959-7; p. 120 During Fitrat's stay in Istanbul,Sayyid Mir Muhammad Alim Khan

Emir Sayyid Mir Muhammad Alim Khan ( uz, Said Mir Muhammad Olimxon, 3 January 1880 – 28 April 1944) was the last emir of the Uzbek Manghit dynasty, rulers of the Emirate of Bukhara in Central Asia. Although Bukhara was a protectorate of the R ...

had taken over the throne of the Emirate of Bukhara after his father's death. The new emir's announcements of sociopolitical reforms caused Fitrat to initially express his sympathy toward him and to urge the local ulama

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious ...

to support the emir's initiatives. As archive documents show, it was in 1914 that Fitrat started to act in an amateur theater in Bukhara.

According to Sadriddin Ayni

Sadriddin Ayni ( tg, Садриддин Айнӣ, fa, صدرالدين عينى, russian: Садриддин Саидмуродович Саидмуродов; 15 April 1878 – 15 July 1954) was a Tajik intellectual who wrote poetry, fiction, j ...

, at that time Fitrat's literary work revolutionised the cosmos of ideas in Bukhara. In 1915 in his work ''Oila'' ("Family"), Fitrat was one of the first reformers to write about the hard life of women in Turkestan.Dilorom Alimova: ''The Turkestan Jadids’ Conception of Muslim Culture''. In: Gabriele Rasuly-Paleczek, Julia Katschnig: ''Central Asia on Display. Proceedings of the VII. Conference of the European Society for Central Asian Studies'' (p. 143–147; translated from Russian by Kirill F. Kuzmin and Sebastian Stride), Münster 2005; p. 145 Another text written in this timeframe is a schoolbook about the history of Islam, meant for use in reformed schools, and a collection of patriotic poems. In ''Rohbari najot'' ("The guide to salvation", 1916) he explained his philosophy on the basis of the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , s ...

. He became a member of the Young Bukharans

The Young Bukharans ( fa, جوانبخارائیان; uz, Yosh buxoroliklar) or Mladobukharans were a secret society founded in Bukhara in 1909, which was part of the jadidist movement seeking to reform and modernize Central Asia along Wester ...

and met Fayzulla Khodzhayev Faizullah, also spelled Fayzullah or Feizollah ( ar, فيزالله ) is a male Muslim given name, composed of the elements '' Faiz'' and ''Allah''. It means ''Success from God'' or ''Victory from God''. In modern usage it may appear as a surname. ...

in 1916. Subsequently, his ties to panturkism

Pan-Turkism is a political movement that emerged during the 1880s among Turkic intellectuals who lived in the Russian region of Kazan (Tatarstan), Caucasus Viceroyalty (1801–1917), Caucasus (modern-day Azerbaijan) and the Ottoman Empire ( ...

grew stronger, and in 1917 Fitrat started to predominantly use a puristic Turkic tongue in his publications. In early 1917 he met Choʻlpon, who went on to be one of his closest friends for the rest of his life.

Until 1917 Fitrat and other members of his movement were hopeful that the Bukharan emir would take a leading role in the task of reforming Bukhara.Khalid 2015, p. 41 However, in April 1917 Fitrat had to flee the city because of the growing level of repression. He firstly went to Samarkand, where in August (edition 27) he became columnist and publisher of the newspaper ''Hurriyat''.Allworth 2000, p. 13Khalid 1998, p. 291f He stayed in this position until 1918 (edition 87). In late 1917, together with Usmonxoʻja oʻgʻli he penned a reformist agenda on behalf of the Central Committee of the Young Bukharan party. In it he proposed the implementation of a constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

under the leadership of the emir and with the sharia as the legal basis. This programme was adopted by the Central Committee in January 1918 with minor changes.

After Kolesov's unsuccessful campaign in March 1918 Fitrat went on to Tashkent

Tashkent (, uz, Toshkent, Тошкент/, ) (from russian: Ташкент), or Toshkent (; ), also historically known as Chach is the capital and largest city of Uzbekistan. It is the most populous city in Central Asia, with a population of 2 ...

(then part of the Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic

The Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (initially, the Turkestan Socialist Federative Republic; 30 April 191827 October 1924) was an autonomous republic of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic located in Soviet Central A ...

), where he worked in the Afghan

Afghan may refer to:

*Something of or related to Afghanistan, a country in Southern-Central Asia

*Afghans, people or citizens of Afghanistan, typically of any ethnicity

** Afghan (ethnonym), the historic term applied strictly to people of the Pas ...

consulateAllworth 1990, p. 301 and where he served as an organizer of the nationalist intellectuals.Edward A. Allworth: ''The Changing Intellectual and Literary Community''. In: Edward A. Allworth: ''Central Asia, 120 Years of Russian Rule'' (p. 349–396); p. 371 In Tashkent he founded the multi-ethnic literature group '' Chigʻatoy gurungi'' ("Chagataian discussion forum"). During the next two years, this was the breeding ground of a growing Chagataian nationalism. His text ''Temurning sogʻonasi'' (" Timur's mausoleum", 1918) showed a turn towards Pan-Turkism: A "son of a Turkic people" and "watcher of the border of Turan

Turan ( ae, Tūiriiānəm, pal, Tūrān; fa, توران, Turân, , "The Land of Tur") is a historical region in Central Asia. The term is of Iranian origin and may refer to a particular prehistoric human settlement, a historic geographical re ...

" prays for the resurrection of Timur at his grave and the rebuilding of the Timurid Empire

The Timurid Empire ( chg, , fa, ), self-designated as Gurkani (Chagatai language, Chagatai: کورگن, ''Küregen''; fa, , ''Gūrkāniyān''), was a PersianateB.F. Manz, ''"Tīmūr Lang"'', in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Online Edition, 2006 Tu ...

.

After having been critical about the February Revolution and the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

' coming into power the publication of secret treaties between the Tsardom, Great Britain and France by the Bolsheviks and the decline of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

made him realize "who the real enemies of the Muslim, and especially the Turkic, world are": As he thought, the British now had the whole Arab world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western A ...

- with the exception of Hejaz - under their control and were enslaving 350 million Muslims. Since he felt it was their duty to be enemies of the British, Fitrat now supported the Soviets.Khalid 1998, p. 293f This view provoked resistance by fellow Young Bukharans

The Young Bukharans ( fa, جوانبخارائیان; uz, Yosh buxoroliklar) or Mladobukharans were a secret society founded in Bukhara in 1909, which was part of the jadidist movement seeking to reform and modernize Central Asia along Wester ...

like Behbudiy, Ayni and others. Nevertheless, in his analysis of Asian politics (''Sharq siyosati'', "Eastern politics", 1919), Fitrat argued for a strategic alliance between the Muslim world and Soviet Russia and against the politics of European powers which controlled India, Egypt and Persia, therefore especially against Britain.

During his exile Fitrat and his party wing inside the Young Bukharans became members of the Communist Party of Bukhara. In June 1919 he was elected into the Central Committee during the first party congress. Thereupon Fitrat worked in the party press, taught in the first Soviet schools and institutes of higher education, and edited the sociopolitical and literary journal ''Tong'' ("Dawn"), a publication of the Communist Party of Bukhara, in April and May 1920.

Sarfraz Khan suggests that by 1920 Fitrat had accepted that his reform ideas would not be transacted in the emirate. Because of that he started to endorse the idea that the emirate should be replaced by a people's republic. Together with his comrades he organized the Turkestan Bureau of the Young Bukharan Party under the leadership of Khodzhayev, which mobilized against the emir parallel to the Communist Party of Bukhara.Sarfraz Khan: ''Abdal Rauf Fitrat''. In: ''Religion, State & Society'', vol. 24, no. 2/3 (p. 139–157), 1996. p. 153

Fitrat as statesman in the people's republic

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

under Mikhail Frunze

Mikhail Vasilyevich Frunze (russian: Михаил Васильевич Фрунзе; ro, Mihail Frunză; 2 February 1885 – 31 October 1925) was a Bolshevik leader during and just prior to the Russian Revolution of 1917. Born in the modern-day ...

. Fitrat returned to Bukhara in December 1920 with a scientific expedition whose goal was to collect Bukhara's rich cultural heritage. After that, he took part in the state leadership of the new Bukharan People's Soviet Republic, starting as the head of the national ''Waqf

A waqf ( ar, وَقْف; ), also known as hubous () or '' mortmain'' property is an inalienable charitable endowment under Islamic law. It typically involves donating a building, plot of land or other assets for Muslim religious or charitab ...

'' authority until 1921, later as foreign minister (1922), minister of education (1923), deputy chairman of the council for work of the Bukharan People's Soviet Republic and momentarily as minister for military and finances (1922).

In March 1921, Fitrat ordered the language of instruction to be changed from Persian to Uzbek, which also became the official language of Bukhara. The next year Fitrat sent 70 students to Germany so they could teach at the newly founded University of Bukhara after their return. During his time as minister for education Fitrat implemented changes in the instruction at madrasahs,William Fierman: ''Language Planning and National Development. The Uzbek Experience''. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin/New York 1991, ISBN 3-11-012454-8 (''Contributions to the sociology of languages'', vol. 60). p. 235 opened the "School for Oriental Music"Alyssa Moxley: ''The concept of traditional music in Central Asia: From the Revolution to independence''. In: Sevket Akyildiz, Richard Carlson (ed.): ''Social and Cultural Change in Central Asia: The Soviet legacy'' (p. 63–71). Routledge; London, New York 2013, ISBN 9781134495139; p. 64 and supervised the gathering of the country's cultural heritage. With commentaries on fatwas and with guidelines regarding which sources of law local mufti

A Mufti (; ar, مفتي) is an Islamic jurist qualified to issue a nonbinding opinion (''fatwa'') on a point of Islamic law (''sharia''). The act of issuing fatwas is called ''iftāʾ''. Muftis and their ''fatwas'' played an important role ...

s should use Fitrat, as minister for education, also exerted influence on jurisdiction.

After their reunion with the communists, Young Bukharans dominated the power structure of the people's republic. Fitrat and like-minded companions managed to coexist with the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

for some time, but Basmachi activists in the center and the east of the republic and a dispute about the presence of Russian troops overcomplicated the situation. Fitrat voiced his disapproval of Bolshevik misjudgments in Central Asian affairs in his ''Qiyomat'' ("The Last Judgment", 1923).Allworth 2000, p. 14 Together with the head of government, Fayzulla Khodzhayev Faizullah, also spelled Fayzullah or Feizollah ( ar, فيزالله ) is a male Muslim given name, composed of the elements '' Faiz'' and ''Allah''. It means ''Success from God'' or ''Victory from God''. In modern usage it may appear as a surname. ...

, he tried without success to ally with Turkey and Afghanistan to secure Bukhara's independence

Instigated by the Soviet plenipotentiary the then political leaders with nationalist tendencies,Adeeb Khalid: ''Islam after Communism: Religion and Politics in Central Asia''. University of California Press; Berkeley, Los Angeles, London 2007, ISBN 978-0-520-28215-5; p. 58 including Fitrat, but not Khodzhayev, were ousted and expulsed to Moscow on 25 June 1923. Fitrat's ''Chigʻatoy gurungi'', which the pro-Soviets considered an "antirevolutionary bourgeois nationalist organization", was also closed down in 1923.Sarfraz Khan: ''Muslim Reformist Political Thought. Revivalists, Modernists and Free Will''. Routledge, London/New York 2003, ISBN 978-1-136-76959-7; p. 121

Fitrat's career as a scholar

After Bukhara had lost its independence and changed side from nationalism and Muslim reformism to secular

After Bukhara had lost its independence and changed side from nationalism and Muslim reformism to secular communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

, Fitrat wrote a number of allegories

As a literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a hidden meaning with moral or political significance. Authors have used allegory th ...

in which he criticized the new political system in his homeland.Allworth 2000, p. 15 He had unavoidably withdrawn from politics and committed himself to teaching. Between 1923 and 1924 he spent 14 months in exile in Moscow. According to Adeeb Khalid little is known about Fitrat's time in Moscow, even though it was highly productive. According to Uzbek scholars Fitrat worked at the Lazarev Institute of Oriental Languages

The Lazarev Institute of Oriental Languages, ( hy, Լազարևի արևելյան լեզուների ինստիտուտ) established in 1815, was a school specializing in orientalism, with a particular focus on that of Armenia, and was the princi ...

in Moscow, and later received the title of professor from the Institute for Oriental Studies at Petrograd (St. Petersburg) University, but, according to Khalid, there is no documentary evidence for these claims.

After his return to Central Asia in September 1924 there was dispute between former Tashkent Young Communists around Akmal Ikramov

Akmal Ikramovich Ikramov (Russia: Акмаль Икрамович Икрамов; Uzbek: Akmal Ikromovich Ikromov; 1898 – 13 March 1938) was an Uzbek politician active in Uzbek SSR politics and served as the First Secretary of the Central Co ...

and former Young Bukharans around Fayzulla Khodzhayev regarding Fitrat's persona in the newly established Uzbek SSR

Uzbekistan (, ) is the common English name for the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic (Uzbek SSR; uz, Ўзбекистон Совет Социалистик Республикаси, Oʻzbekiston Sovet Sotsialistik Respublikasi, in Russian: Уз ...

. Khodzhayev stood up for Fitrat and was, according to Adeeb Khalid, at least partially responsible for Fitrat's freedom and ability to keep publishing. Fitrat avoided serious involvement in the affairs of the new state and is said to have declined the option to teach at the Central Asian Communist University or to work permanently at the Commissariat of Education.

Subsequently, he taught at several colleges in the Uzbek SSR

Uzbekistan (, ) is the common English name for the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic (Uzbek SSR; uz, Ўзбекистон Совет Социалистик Республикаси, Oʻzbekiston Sovet Sotsialistik Respublikasi, in Russian: Уз ...

, after 1928 at Samarkand University. In the same year, he became a member of the Academic Council of the Uzbek SSR. In his academic activity as historian of literatureEdward A. Allworth: ''Fitrat, Abdalrauf (Abdurauf)''. In: Steven Serafin: ''Encyclopedia of World Literature in the 20th Century: E-K'' (p. 119f), 1999; p. 119 he stayed true to his own beliefs rather than to the conformity demanded by the Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

.Allworth 2000, p. 17 After 1925, this included criticism against the communist theory of national cultures in the supra-ethnic Supraethnicity (from Latin prefix / "above" and Ancient Greek word / "ethnos = people") is a scholarly neologism, used mainly in social sciences as a formal designation for a particular structural category that lies "above" the basic level of eth ...

structure of Central Asia, which brought him the reputation of a political subversive

Subversion () refers to a process by which the values and principles of a system in place are contradicted or reversed in an attempt to transform the established social order and its structures of power, authority, hierarchy, and social norms. Sub ...

in Communist circles.Allworth 2002, p. 16 The communists believed to recognize hidden messages in Fitrat's works and accused him of political subversion. Meanwhile, a new generation of Soviet writers had formed in Uzbekistan's literary scene. During this phase of his life Fitrat married the approximately 17-year-old Fotimaxon, a sister of Mutal Burhonov, who would leave Fitrat after a short time.

Fitrat wrote two works dealing with Central Asian Turk languages (in 1927 and 1928), in which he denied the necessity to segregate Soviet Central Asia along ethnic lines. Around this time Communist ideologues, the next generation of writers and the press began criticizing Fitrat's perspective towards questions of nationality and labelling his way of presenting classics of Chagataian literature as "nationalist", thus non-Soviet. This "Chagataiism" would later be one of the heaviest accusations against Fitrat.Allworth 1990, p. 226 In this campaign Jalil Boyboʻlatov, a chekist who had pursued Fitrat since the time of the Bukharan People's Soviet Republic and now analyzed Fitrat's writings on the history of literature, was a pivotal character.

Fitrat wrote his last book with political relevance on Emir Alim Khan in Persian ( Tajik) in 1930.Allworth 2000, p. 26 After 1932, Fitrat became a powerful control instance of political and social activity in his homeland.Allworth 2000, p. 18 Fitrat felt the necessity to acquaint the following generation of literates with the traditional rules of prosody ( aruz), since by the 1930s the Uzbek language had become emphatically contemporary and ruralist and therefore detached from historical poetry.

From 1932 onwards writers had to be member of the writers' union in order to have their texts published. During this time Fitrat wrote a poem in praise of cotton which was published in a Russian language anthology. Apart from this instance Fitrat was technically excluded from the press and dedicated himself to teaching. He eventually received the title of professor from the Institute of Language and Literature in Tashkent, but in the mid-1930s he was attacked by his students on a regular basis. His last play, ''Toʻlqin'' ("the wave", 1936), was a protest against the practice of censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governments ...

.

The end in the Great Purge

On the night of 23 April 1937 Fitrat's home was paid a visit byNKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

forces and Fitrat was arrested the following day. For over 40 years his further fate was unknown to the public. Only the release of archive material during the era of glasnost revealed the circumstances of Fitrat's disappearance.

Fitrat was suspected to be a member of a

Fitrat was suspected to be a member of a counter-revolutionary

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "counter-revolut ...

nationalist organization who had tried to recruit young writers for his ideas, who had compiled texts in the spirit of counter-revolutionary nationalism, and who had striven for splitting off a bourgeois Turanic state from the Soviet Union. He was prosecuted as "one of the founders and leaders of the counter-revolutionary nationalist jadidism" and as an organizer of a "nationalist pan-Turkic counter-revolutionary movement against the party and the Soviet government" according to articles 67 and 66 (1) of the criminal code of the Uzbek SSR. Referring to archival documents Begali Qosimov reports that these and further allegations were investigated for months, and finally Fitrat was also accused of treason according to article 57 (1). According to secret files, Fitrat broke during questioning and was willing to admit any ideological crime.

The case was discussed on 4 October 1938 by the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union

The Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union ( Russian: Военная коллегия Верховного суда СССР, ''Voennaya kollegiya Verkhovnogo suda SSSR'') was created in 1924 by the Supreme Court of the Sov ...

, whereupon, according to the transcript, a 15 minutes long show trial took place the following day without hearing witnesses. The trial ended with Fitrat's sentence to death by a firing squad and confiscation of all goods. Archival documents show that the execution was carried out on 4 October 1938, thus on the day before his conviction.

Said archival documents also show that at the time of his arrest Fitrat was living together with his mother, his 25-year-old wife Hikmat and his 7-year-old daughter Sevar in the mahallah

is an Arabic word variously translated as district, quarter, ward, or "neighborhood" in many parts of the Arab world, the Balkans, Western Asia, the Indian subcontinent, and nearby nations.

History

Historically, mahallas were autonomous social i ...

of Guliston in the city of Tashkent. His wife was arrested together with Fitrat, but released in January 1938. 1957, after Fitrat's rehabilition, an apology was communicated to her.

Legacy and criticism

In the beginning, the Soviet Union discouraged the memory of Fitrat and his followers. After the celebrations at Ali-Shir Nava'i's 500th birthday according to theIslamic calendar

The Hijri calendar ( ar, ٱلتَّقْوِيم ٱلْهِجْرِيّ, translit=al-taqwīm al-hijrī), also known in English as the Muslim calendar and Islamic calendar, is a lunar calendar consisting of 12 lunar months in a year of 354 ...

in 1926 the Soviets held another celebration in the year of 1941, during Nava'i's 500th birthday according to the solar calendar. Instead of remembering a master of Chagatai literature, these celebrations remembered the "father of Uzbek literature" and were labelled as the "triumph of Leninist-Stalinist nationality politics". Fitrat's texts were banned until Stalin's death like those of the other Uzbekistani literates who became victims of the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secret ...

in October 1938. Nevertheless, they were circulating among students and intellectuals. In the Third Reich

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, ''Hind ixtilolchilari'' was published again in 1944 with the participation of Annemarie von Gabain

Annemarie von Gabain (7 April 1901—15 January 1993) was a German scholar who dealt with Turkic studies, both as a linguist and as an art historian.

Early life and education

Gabain was born in Morhange on 7 April 1901. Her father, Arthur von Ga ...

for the purpose of anti-Soviet propaganda.

While he was posthumously rehabilitated in 1956Shawn T. Lyons: ''Abdurauf Fitrat's Modern Bukharan Tragedy''. In: Choi Han-woo''International Journal of Central Asian Studies''; Volume 5

(PDF; 179 kB). The International Association of Central Asian Studies, 2000. due to the activity of the critic Izzat Sulton and his achievements in the areas of literature and education now recognized, the Soviet press continued criticizing him for his liberal and the Tajiks for his Turkophile tendencies. Almost all his works remained banned until perestroika. However, some copies of Fitrat's dramas were preserved in academic libraries. For a long time, Fitrat was remembered as an Uzbek or Turkish nationalist.Bert G. Fragner: ''Traces of Modernisation and Westernisation? Some Comparative Considerations concerning Late Bukhāran Chronicles''. In: Hermann Landolt, Todd Lawson: ''Reason and Inspiration in Islam: Theology, Philosophy and Mysticism in Muslim Thought. Essays in Honour of Hermann Landolt'' (p. 542–565), New York 2005; p. 555 While his prose started being recognized by Uzbek scholars of literature in the 1960s and '70s and several stories were once again published, explicitly negative comments were still in circulation up to the '80s. Even in the '90s sources on Fitrat in Uzbekistan were still scarce. Only after 1989 several works of Fitrat were printed in Soviet magazines and newspapers. According to Halim Kara's studies three historical periods of Fitrat's rehabilitation can be distinguished in Uzbekistan: In the course of de-Stalinization the then First Secretary of the Uzbek Central Committee of the

Communist Party of Uzbekistan

The Communist Party of Uzbekistan (russian: Коммунистическая партия Узбекистана, uz, Ўзбекистон Коммунистик Партияси), initially known as Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Uzbekistan, ...

Nuritdin Mukhitdinov announced the rehabilitation of Fitrat and other Jadid writers, however, unlike Abdulla Qodiriy Fitrat did not receive an ideological reassessment. Fitrat was still portrayed as a bourgeois nationalist and opponent to socialist ideology. This picture was also drawn in the Uzbek Soviet Encyclopedia which was published between 1971 and 1980.

The second period corresponds with the time of perestroika. Due to Temur Poʻlatov's call the Uzbek Writers' Union built a commission in 1986 whose task was to investigate Choʻlpon's and Fitrat's literary heritage. The allegations against Fitrat of before essentially were not removed, but the pro-Soviet phase of his oeuvre was now acknowledged. Certain texts, particularly those written under Bolshevik power, were republished with commentaries by literature critics as supplement. The reevaluation of Fitrat's controversial works in the light of Marxist–Leninist ideology which was initially planned by the commission could, according to Kara, not be carried out under the control of the conservative government of the Uzbek SSR of that time. However, the commission's conclusions and the principle of glasnost made further discourse possible. A group of conservative writers like Erkin Vohidov

Erkin Vohidov ( uz, Erkin Vohidov / Эркин Воҳидов; December 28, 1936 – May 30, 2016) was an Uzbek poet, playwright, literary translator, and statesman. In addition to writing his own poetry, Vohidov translated the works of many ...

tried to bring Fitrat's texts into accordance with the applicable principles of Soviet literary politics and to explain the "ideological errors" as misunderstanding or lack of knowledge of Marxist–Leninist ideology. Another group around the literary critics Matyoqub Qoʻshjonov and Naim Karimov demanded Fitrat's full rehabilitation and the unreserved republication of his writings. For them, Fitrat's work was not ideologically inadmissible. Instead, the importance for the cultural heritage and for the development of a national literature were articulated in this pro-Uzbek trend. As Shawn T. Lyons showed, during perestroika also parts of the general public demanded a complete clarification of the circumstances of Fitrat's disappearance and his full rehabilitation. Contrary to the line of the party, Izzat Sulton classified Fitrat as an important advocate of Soviet socialism

Socialism is a left-wing Economic ideology, economic philosophy and Political movement, movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to Private prop ...

.

The third period Kara analyzed is the Republic of Uzbekistan in independence. The decolonization

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on separatism, in ...

and de-Sovietization of Uzbek national discourses led to Fitrat's works being published again uncensored. In 1991 the Uzbek government awarded the State Prize of Literature to Fitrat and Choʻlpon in recognition of their contribution to the development of modern Uzbek literature and national identity. Fitrat's dedication for an independent Turkestan received a new interpretation by the anti-Russian Uzbek intelligentsia: Now it was the lack of socialist properties that became highlighted. According to Kara, the Uzbek literary elite actually ignores or talks down the pro-Soviet components in Fitrat's work. As Kara explains, distancing Fitrat's oeuvre from the changeable reality of his lifetime is a legacy of Soviet academia, where either positive or negative properties of a person were exaggerated. Kara suggests that this narrative strategy of seeing things in only black or white, with a different backdrop, has now been adopted by the Uzbeks. In 1996, Fitrat's native city of Bukhara dedicated the ''Abdurauf Fitrat Memorial Museum'' to the "eminent public and political figure, publicist, scholar, poet, and expert on the history of the Uzbek and Tajik nations and their spiritual cultures". Alexander Djumaev noted in 2005 that in the recent past Fitrat had received a sanctified status in Uzbekistan and that he frequently got labelled as a martyr (''shahid

''Shaheed'' ( , , ; pa, ਸ਼ਹੀਦ) denotes a martyr in Islam. The word is used frequently in the Quran in the generic sense of "witness" but only once in the sense of "martyr" (i.e. one who dies for his faith); ...

''). In several other Uzbek cities, including the capital Tashkent, streets or schools have been named after Fitrat.

Not only Uzbeks, but also a number of Tajiks claim Fitrat's literary legacy for themselves. Authors like Sadriddin Ayni

Sadriddin Ayni ( tg, Садриддин Айнӣ, fa, صدرالدين عينى, russian: Садриддин Саидмуродович Саидмуродов; 15 April 1878 – 15 July 1954) was a Tajik intellectual who wrote poetry, fiction, j ...

and Mikhail Zand argue in favour of Fitrat's importance for the development of the Tajik language and especially of Tajik literature. Ayni, for example, called Fitrat a "pioneer of Tajik prose". According to the ''Encyclopædia Iranica

''Encyclopædia Iranica'' is a project whose goal is to create a comprehensive and authoritative English language encyclopedia about the history, culture, and civilization of Iranian peoples from prehistory to modern times.

Scope

The ''Encyc ...

'', Fitrat was a pioneer of a simplified Persian literary language that circumvented traditional flourishing.

Other Tajik commentators, however, condemned Fitrat for his Turkist tendency. In an interview in 1997 Muhammadjon Shakuri Muhammadjon Shakuri ( tg, Муҳаммадҷон Шакурӣ, fa, محمدجان شکوری; February 1925, in Bukhara – September 16, 2012, in Dushanbe), also known as Muhammad Sharifovich Shukurov, was a prominent Tajik intellectual and one o ...

, professor at the Tajik Academy of Sciences, referred to the fact that Tajik intellectuals joined the pan-Turkic idea as a mistake and made them responsible for the discrimination of Tajiks during the territorial partitioning of Central Asia. Rahim Masov, another member of the Tajik Academy of Sciences, called Fitrat, Khodzhayev and Behbudiy "Tajik traitors". Tajik president Emomali Rahmon

Emomali Rahmon (; born Emomali Sharipovich Rahmonov, tg, Эмомалӣ Шарӣпович Раҳмонов, script=Latn, italic=no, Emomalī Sharīpovich Rahmonov; ; born 5 October 1952) has been the 3rd President of Tajikistan since 16 Novem ...

too has joined the narrative about Tajiks who denied the existence of their own nation.

The fact that in 1924 ''Hind ixtilolchilari'' („Indian rebels“, 1923) received an award by the Azerbaijani People's Commissariat for Education proofs that Fitrat's writings were appreciated beyond the limits of Transoxania.Kleinmichel 1993, p. 144 According to Fitrat's sister, this work was translated into Indian languages and staged at theatres in India. Its significance for the Indian fight for liberation was attested by Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

.

Ideological and political classification

According to Hélène Carrère d’Encausse, Fitrat was the ideological leader of the jadidist movement. The scholar of IslamAdeeb Khalid

Adeeb Khalid (born February 17, 1964) is associate professor and Jane and Raphael Bernstein Professor of Asian Studies and History in the history department of Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota. His academic contributions are highly cited ...

describes Fitrat's interpretation of history as "recording of human progress". As with other reformers, Fitrat was interested both in the glorious past of Transoxania as well as the present state of degradation which he observedHélène Carrère d’Encausse: ''Social and Political Reform''. In: Edward A. Allworth: ''Central Asia, 120 Years of Russian Rule'' (p. 189–206), Durham, London 1989; p. 205 and which the jadidists became aware of through their stay abroad. Similarly to Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī, Fitrat was searching for reasons for the spiritual and temporal decay of the Muslim world. Additionally, both al-Afghānī and Fitrat saw it as the duty of the Muslims themselves to change the present state of things. Fitrat, who especially had an eye on the case of Bukhara, saw the reason for the state of his native city in the development of Islam into a religion for the rich. He proposed a reform of the education system and the introduction of a dynamic form of religion, freed from phantasy, ignorance and superstition, in which single individuals would be in the focus.Carrère d’Encausse 1965, p. 932f

For Fitrat, the Emirate of Bukhara was characterized by corruption, abuse of power, and violence. Fitrat criticized both the clerics ''(ulama

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious ...

)'' as well as the worldly rulers and the people: While the clerics had divided and therefore weakened the Muslim community, the others had followed them and the emir "like sheeps". According to Khalid, Fitrat's writings from his days of exile in Moscow show a swing from anticlericalism to scepticism and irreligion. In one of the few surviving autobiographical statements by Fitrat, dating from 1929, he explained that he had wanted to separate religion from superstition. However, as he continued, he had realized that "nothing remained of religion once it was separated from superstition", which had led him towards irreligion (''dinsizliq''). As per Khalid, as early as in 1917 Fitrat had given up on Islamic reformism in favor of insistent Turkism.

Fitrat's reformism did not aim at an orientation on Western cultures: According to him, the success of the West came out of originally Islamic principles. For example, in ''Bayonoti ayyohi hindi'' he cites the words of the French historian Charles Seignobos

Charles Seignobos (b. 10 September 1854 at Lamastre, d. 24 April 1942 at Ploubazlanec) was a French scholar of historiography and an historian who specialized in the history of the French Third Republic, and was a member of the Human Rights Lea ...

on the greatness of the medieval Muslim civilization. In ''Sharq siyosati'' he wrote: "Up until today, European imperialists have given nothing to the East but immorality and destruction." On the other hand, Fitrat criticized heavily against the refusal of innovation coming from Europe by the Muslim leaders of Bukhara. This "cloak of ignorance" prevented, as per Fitrat, that Islam could be defended by means of enlightenment.

In 1921 Fitrat wrote that there were three kinds of Islam: the religion from the Quran, the religion of the ''ulama'' and the faith of the masses. The last of these he described as superstition and fetishism

A fetish (derived from the French , which comes from the Portuguese , and this in turn from Latin , 'artificial' and , 'to make') is an object believed to have supernatural powers, or in particular, a human-made object that has power over ot ...

, the second of the aforementioned as hindered by outdated legalism. Fitrat rejected the principle of taqlid

''Taqlid'' (Arabic تَقْليد ''taqlīd'') is an Islamic term denoting the conformity of one person to the teaching of another. The person who performs ''taqlid'' is termed ''muqallid''. The definite meaning of the term varies depending on con ...

; in his world of thought knowledge should be exposed to intellectual critique. Also, it should be possible to obtain this knowledge with reasonable effort, and it had to be helpful to humankind in modernity. He was against sticking to a scholasticism that was "of no assistance to humans in the modern world". In Fitrat's view, the task of regenerating the Muslim society required spiritual renovation and political and social revolution. For him, taking part in these jadidist activities was the "duty of every single Muslim".

He argued in favor of reforms in family relations, especially improvements in the status of women. Citing a hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approva ...

that it is every Muslim' duty to pursue knowledge, he argued for the importance of women's education, in order for them to be able to pass on their knowledge to their children. Based on the Quran and on hadiths he talked about the importance of hygiene and demanded that Russian or European teachers be recruited for a school of medicine in Bukhara. Additionally, he deduced the backwardness of the Bukharan society from the practice of pederasty

Pederasty or paederasty ( or ) is a sexual relationship between an adult man and a pubescent or adolescent boy. The term ''pederasty'' is primarily used to refer to historical practices of certain cultures, particularly ancient Greece and an ...

.

What Fitrat demanded was less a compromise between western and Islamic values and more a clean break with the past and a revolution of human concepts, structures and relations with the end goal of freeing '' Dār al-Islām'' from the infidels. As per Hélène Carrère d’Encausse Fitrat's revolutionary tone and his refusal of compromise were peculiarities that set him apart from other Muslim reformers, such as al-Afghani oder Ismail Gasprinsky. Fitrat was aware that the path toward social progress would be complicated and long. According to the scholar Sigrid Kleinmichel he articulated this by "projecting the revolutionary aims and arguments onto historical attempts at renewal whose outcome did not justify the effort". As their model Young Bukharans like Fitrat rather had examples of Muslim reformism, especially from the late Ottoman empire, than Marxism. The repeated use of India as setting for Fitrat's works is no coincidence. Sigrid Kleinmichel identified several motives for this peculiarity; the anti-British orientation in the Indian struggle for independence (while the Emir of Bukhara was drawn towards the British), the movements' broad possibilities for alliances, the developing Indian national identity, congruent ideas for the overcoming of backwardness (like with Muhammad Iqbal

Sir Muhammad Iqbal ( ur, ; 9 November 187721 April 1938), was a South Asian Muslim writer, philosopher, Quote: "In Persian, ... he published six volumes of mainly long poems between 1915 and 1936, ... more or less complete works on philos ...

) and the pro-Turkishness of parts of the Indian independence movement.

Fitrat's ideas of a good Muslim and of a patriot were, according to Carrère d’Encausse, closely linked to each other. Moreover, Fitrat pushed the idea of unity of all Muslims regardless of their affiliation to, for example, Shia

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his successor (''khalīfa'') and the Imam (spiritual and political leader) after him, mo ...

or Sunni Islam. William Fierman, however, described Fitrat primarily as a Bukharan patriot, who also had a strong identity as a Turk and, less pronounced, as a Muslim. According to Fierman, in the case of Fitrat the contradictions between pan-Turkic and Uzbek identity can be identified: As per Fitrat, the Ottoman and Tatar Turkic languages had been on the receiving end of too much foreign influence. Contrary to that, the main goal of Fitrat's Uzbek language policies was to ensure the language's purity. He did not want this ideal to be subordinated to Turkic unity: Turkic unity, according to Fitrat, could only be achieved after purifying the language. Fitrat wanted to take the Chagatai language

Chagatai (چغتای, ''Čaġatāy''), also known as ''Turki'', Eastern Turkic, or Chagatai Turkic (''Čaġatāy türkīsi''), is an extinct Turkic literary language that was once widely spoken across Central Asia and remained the shared litera ...

as the basis for such a unified Turkic tongue. Ingeborg Baldauf called Fitrat the personification of "Chaghatay nationality"; Adeeb Khalid indicates the necessity of distinguishing the concept of Pan-Turkism from the Turkism articulated by Central Asian intellectuals: According to Khalid, the Central Asian Turkism is celebrating the history of Turkestan and its very own historical heroes.

While Soviet ideologues denounced Fitrat's "Chagataiism" as nationalist, Edward A. Allworth

Edward A. Allworth (December 1, 1920 – October 20, 2016) was an American historian specializing in Central Asia. Allwarth was widely regarded as the West’s leading scholar on Central Asian studies. He extensively studied the various et ...

saw him as a convinced Internationalist

Internationalist may refer to:

* Internationalism (politics), a movement to increase cooperation across national borders

* Liberal internationalism, a doctrine in international relations

* Internationalist/Defencist Schism, socialists opposed to ...

since young age, who was forced to deny his opinions. Hisao Komatsu wrote that Fitrat was a "patriotic, Bukharan intellectual"., but that his understanding of '' watan'' had changed over time: Initially, he had only referred to the city of Bukhara with this term, but later he included the entire emirate, and finally all of Turkestan. According to Sigrid Kleinmichel, the accusations of nationalism and Pan-Islamism against Fitrat have always been "general, never analytical".

Work analysis

Statistical and thematical developments

A list of the works of Abdurauf Fitrat, compiled byEdward A. Allworth

Edward A. Allworth (December 1, 1920 – October 20, 2016) was an American historian specializing in Central Asia. Allwarth was widely regarded as the West’s leading scholar on Central Asian studies. He extensively studied the various et ...

, covers 191 texts written during 27 years of active work between 1911 and 1937. Allworth sorts these texts into five subject categories: Culture, economy, politics, religion and society. An analysis of all 191 texts has the following result:

Two thirds of Fitrat's works deal with the subject of "culture" (broadly construed) while some 20 percent of his texts deal with political matters, which was his main subject in his early years. The political texts mostly originate during his active engagement in the jadid movement and in the government of the Bukharan People's Soviet Republic. After the creation of the Uzbek SSR and the Tajik ASSR

The Tajik Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Tajik ASSR) (russian: Таджикская Автономная Социалистическая Советская Республика) was an autonomous republic within the Uzbek SSR in the Sovi ...

in 1924/25 and especially after the Communist Party started exercising strong control over culture and society, Fitrat wrote less on political matters. Even though Communists accused Fitrat of deviating from the party line in his texts on culture, they are decidedly less political than his earlier texts.

According to Allworth, the reason for the almost complete disappearance of texts on society after 1919 was a missing secure opportunity of discussing non-orthodox interpretations. Fitrat reacted to restrictions on press freedom by stopping to freely express his political views in print and by choosing subjects that followed Bolshevik notions of society. Questions of family and education were exclusively discussed before 1920. Some of the most important works of Fitrat from the 1920s are his poems examining group identity.

Similar categorizations of Fitrat's work can be found in a list of 90 works in 9 categories from 1990, a list of 134 titles compiled by Ilhom Gʻaniyev in 1994 and Yusuf Avcis list from 1997. An issue is the disappearance of at least ten of Fitrat's works and the unclear dating of others, for example of ''Muqaddas qon'', which was written sometime between 1917 and 1924. There are different dates for ''Munozara'' as well, but according to Hisao Komatsu Allworth's dating of 1327 AH (1911/1912) can be called "convincing".

Like many Central Asians, Fitrat started his writings with poems and later penned prose, dramas, journalistic works, comedies, political commentary, studies on the history of literature and the politics of education as well as polemical and ideological writings. Fitrat republished many of his earlier works in a reworked form or translated into another language.

Language and script

According to Allworth, Fitrat's first language was - typically for an urban Bukharan of his time - Central Asian Persian (Tajik); the traditional language of education wasArabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

. When Fitrat was in Istanbul, Ottoman Turkish language

Ottoman Turkish ( ota, لِسانِ عُثمانى, Lisân-ı Osmânî, ; tr, Osmanlı Türkçesi) was the standardized register of the Turkish language used by the citizens of the Ottoman Empire (14th to 20th centuries CE). It borrowed exten ...

and Persian were in use there. Fitrat had a personal aversion to the broken Turki (dialectal Uzbek) in use in Tashkent which he taught himself out of a dictionary. Contemporary analyses describe Fitrat's Turki as "peculiar" and speculate that he learned the language without prolonged contact with native speakers. Additionally, according to Allworth, Fitrat spoke Urdu

Urdu (;"Urdu"

'' Russian Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including: *Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries *Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

; according to Adeeb Khalid, however, Fitrat did not speak any European language, and he doubts that Fitrat had functional knowledge of Russian. Borjian sees the question of Fitrat's first language as open.

Until the beginning of the political upheaval in Bukhara, Fitrat had published nearly exclusively in Persian (Tajik) language. His Persian writings of that time were, as per Adeeb Khalid, new not only in the sense of content but also because of their style: simple, direct and close to the spoken language.Khalid 2015, p. 306 However, in 1917 he changed over to a highly purist Turki, in which he even explained some words in footnotes. The aim of Fitrat's ''Chigʻatoy gurungi'' was the creation of a unified Turkish language on the basis of Chagataian language and literature, which was to be achieved by the distribution of the classic works of Navoiy and others and the purification from foreign influences (from Arabic, Persian and Russian) on Turki.

In an article titled ''Tilimiz'' ("Our language") of 1919 Fitrat called the Uzbek language the "unhappiest language of the world". He defined its protection from external influence and the improvement of its reputation as additional goals to his target of purifying the literary language.

In these days, Fitrat denied that Persian was one of Central Asia's native languages. Assuming that the entire population of the region was Turkic notwithstanding the language they actually used in their everyday life was part of his Chagatayist body of thought. According to reports, as minister of education Fitrat forbade the use of Tajik in his office. Literature about Fitrat suggests that a reason for his radical change from Persian to a Turkic language lies in the fact that the Jadid movement linked the Persian tongue to repressive regimes like the one of the Bukharan emir, while Turkic languages were identified with Muslim, that is Tatar and Ottoman, reformism.

In ''Bedil'' (1923), a bilingual work with passages in Persian and Turkic, Fitrat presents an Uzbek tongue influencesd by the Ottoman language as a counterpart to the traditional Persian poetic language, and therefore as a language suited for modernization. His partial return to Tajik during the 1920s can, according to Borjian, be ascribed to the end of Jadidism and the beginning of the suppression of Turkish nationalisms. Tajik national identity emerged later than was the case with Central Asia's Turks. Therefore, the creation of the '' Russian Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including: *Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries *Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

Tajik SSR

The Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic,, ''Çumhuriji Şūraviji Sotsialistiji Toçikiston''; russian: Таджикская Советская Социалистическая Республика, ''Tadzhikskaya Sovetskaya Sotsialisticheskaya Resp ...

in 1929, out of the Tajik ASSR

The Tajik Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Tajik ASSR) (russian: Таджикская Автономная Социалистическая Советская Республика) was an autonomous republic within the Uzbek SSR in the Sovi ...

which had been a part of the Uzbek SSR

Uzbekistan (, ) is the common English name for the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic (Uzbek SSR; uz, Ўзбекистон Совет Социалистик Республикаси, Oʻzbekiston Sovet Sotsialistik Respublikasi, in Russian: Уз ...

, "may" (Borjian) have motivated Fitrat to return to writing in Tajik. In Khalid's perception this step was a kind of exile and an attempt to disprove the allegations of Pan-Turkism. Fitrat himself named the promotion of Tajik drama as the motive.

In Fitrat's time, the Arabic alphabet was predominant, not only as the script of Arabic language texts, but also for texts in Persian and in Ottoman Turkish. After 1923, in Turkestan a reformed Arabic alphabet with better identification of vowels came into use; however, it still could not accommodate the variety of vowels in the Turkic languages.

Fitrat "obviously" ( William Fierman) did not interpret the Arabic alphabet as holy

Sacred describes something that is dedicated or set apart for the service or worship of a deity; is considered worthy of spiritual respect or devotion; or inspires awe or reverence among believers. The property is often ascribed to objects (a ...

or as an important part of Islam: Already in 1921 during a congress in Tashkent, he argued in favour of abolishing all forms of the Arabic letters apart from the initial form. This would have made possible easier teaching, learning and printing of texts. Furthermore, he wanted to abolish all letters which in Uzbek did not represent their own sound (for example the , Ṯāʾ

() is one of the six letters the Arabic alphabet added to the twenty-two from the Phoenician alphabet (the others being , , , , ). In Modern Standard Arabic it represents the voiceless dental fricative , also found in English as the " th" in ...

). In the end, Fitrat's proposal of a fully phonetic orthography which also applied to Arabic loanwords was accepted. Diacritical signs for vowels were introduced and the "foreign" letters were discontinued, but the up to four forms of each letter (for example, ) survived. For Fitrat, the differentiation between "hard" and "soft" sounds was the "soul" of Turkish dialects. The demand to harmonize the orthography of foreign words according to the rules of vowel harmony