1967 Milwaukee Riot on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1967 Milwaukee riot was one of 159

In the immediate aftermath of the riot and marches, little was accomplished in the way of laws, policies, and programs. Speaking of the lack of available funding for enacting proposed reforms, Mayor Maier said:

In the immediate aftermath of the riot and marches, little was accomplished in the way of laws, policies, and programs. Speaking of the lack of available funding for enacting proposed reforms, Mayor Maier said:

race riots

An ethnic conflict is a conflict between two or more contending ethnic groups. While the source of the conflict may be political, social, economic or religious, the individuals in conflict must expressly fight for their ethnic group's positio ...

that swept cities in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

during the "Long Hot Summer of 1967

The long, hot summer of 1967 refers to the more than 150 race riots that erupted across the United States in the summer of 1967. In June there were riots in Atlanta, Boston, Cincinnati, Buffalo, and Tampa. In July there were riots in Birming ...

". In Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee is ...

, Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

, African American residents, outraged by the slow pace in ending housing discrimination and police brutality

Police brutality is the excessive and unwarranted use of force by law enforcement against an individual or a group. It is an extreme form of police misconduct and is a civil rights violation. Police brutality includes, but is not limited to, ...

, began to riot on the evening of July 30, 1967. The inciting incident was a fight between teenagers, which escalated into full-fledged rioting with the arrival of police. Within minutes, arson, looting, and sniping were occurring in the north side of the city, primarily the 3rd Street Corridor.

The city put a round-the-clock curfew into effect on July 31. The governor mobilized the National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

to quell the disturbance that same day, and order was restored on August 3. Although the damage caused by the riot was not as destructive as in such cities as Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at th ...

and Newark

Newark most commonly refers to:

* Newark, New Jersey, city in the United States

* Newark Liberty International Airport, New Jersey; a major air hub in the New York metropolitan area

Newark may also refer to:

Places Canada

* Niagara-on-the ...

, many businesses in the affected neighborhoods were severely damaged. Tensions increased afterward between police and residents. The July disturbance also served as a catalyst to additional unrest in the city; equal housing marches held in August often turned violent as white residents clashed with black demonstrators.

Background

During the mid-1960s, there was race-related civil unrest in a number of major US cities, including riots inHarlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street (Manhattan), 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and 110th Street (Manhattan), ...

and Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

in 1964; Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

in 1965; and Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

and Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

in 1966. During the summer of 1967, a total of 159 race riots

An ethnic conflict is a conflict between two or more contending ethnic groups. While the source of the conflict may be political, social, economic or religious, the individuals in conflict must expressly fight for their ethnic group's positio ...

broke out across the country in what would come to be known as the Long Hot Summer.

Milwaukee communities had long been segregated when Alderwoman Vel Phillips

Velvalea Hortense Rodgers "Vel" Phillips (February 18, 1924 – April 17, 2018) was an American attorney, politician, jurist, and civil rights activist, who served as an alderperson and judge in Milwaukee, Wisconsin and as secretary of Stat ...

, the first woman and African American to hold the position, proposed the first fair housing ordinance in March 1962. She continued to introduce fair housing proposals over the next five years. Four times they were defeated by the city council.

By the summer of 1967, tensions continued to escalate, and protests became increasingly common, including multiple demonstrations outside the private homes of the city's Aldermen. Mayor Henry Maier, the city council, and school board refused to address civil rights grievances, and relations between the police and the residents worsened. As historian Patrick Jones put it, "Blight had surrounded, and then devoured, the heart of Milwaukee's black community."

Recent uprisings in Newark and Detroit, which had broken out July 12 and 23 respectively, only served to make matters worse. LeRoy Jones, then one of 18 black police officers among the total of 2,056 officers in the city's department, described the situation:

There were some rumors that something was going to happen ... We did know there was going to be a riot. The Police Department knew - one to two weeks ahead - that something was planned. It was predicted that it would be on 3rd Street.According to a study that was administered by Karl Flaming, over 95% of all local African Americans did not participate in this disturbance. A majority of the citizens that took part in this riot were young black men who lived in the inner core of Milwaukee. Of the participants, 35% were unemployed and 20% were classified as poor.

Events

July 29

Around midnight on the evening of July 29, a fight broke out between two black women outside the St. Francis Social Center, on the corner of 4th and West Brown streets. A crowd of 350 spectators gathered, and when police arrived to respond to the disturbance, the crowd began to throw rocks at police vehicles. Soon more police came, dressed in riot gear. Some property damage was done but the crowd was quickly dispersed.July 30

The day of Sunday, July 30 was calm, but rumors spread and tensions grew. A large crowd gathered that evening on 3rd Street. It is not clear what event started the outbreak, but at least one story circulated that police had assaulted a young boy. Squire Austin, who was at a civil rights rally, recalled, "The rumor we got ... was that police had beaten up a kid pretty bad over on Third and Walnut ... that's when the looting and firebombing started." By 10:00 PM a crowd of 300 were throwing missiles at stores owned by white residents, starting fires, and looting. The police reacted with violence, and the mob reacted in turn. More fights broke out around 3rd Street, and shootings were reported on Center Street. Along the area from West State street to West Burleigh street looting broke out, multiple shootings occurred, and more fires were set. Just prior to midnight, the mayor went to City Hall to meet with Police Chief Harold Breier. Reports of the first fires came in, along with reports of dispatched firefighters being assailed by stones and prevented from extinguishing them. The mayor requested Governor Warren Knowles notify theWisconsin National Guard

The Wisconsin National Guard consists of the Wisconsin Army National Guard and the Wisconsin Air National Guard. It is a part of the Government of Wisconsin under the control of the Wisconsin Department of Military Affairs. The Wisconsin Natio ...

to be on standby.

July 31

Around 2 AM on July 31, in the area around North 2nd street and West Center street, iron worker Milton L. Nelsen was driving through the mostly black inhabited area, when someone shouted "He's got a gun in the glove compartment." Shotgun fire came from a nearby house, and Nelsen was shot in the face and killed instantly. He left behind a wife and eight children. Hannah Jackson, a bystander, was also hit. The man who fired the gun, John Oraa Tucker, was later charged for the shooting, and maintained he did so out of fear for his and his family's safety. When police responded, officer Bryan Moschea was shot and killed when he entered a building thought to be the location of an unrelated sniper. His badly burned body was not able to be recovered until the following day. Four other officers were wounded. The body of Annie Mosley, aged 77, was found in the burned-out building. She had been shot in the head. Another woman, Willie Ella Green, aged 43, suffered a fatal heart attack running from her second story apartment. The mayor received word of the shootings and fire at West Center at 2:26 AM. He declared astate of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

, and imposed a citywide curfew, which took effect at 3:40 AM. At the Mayor's request, the National Guard was activated.

The mayor lifted the curfew from 4:00 PM to 6:00 PM. This resulted in a rush on downtown and suburban supermarkets. As the story in the ''Milwaukee Journal'' described it:

Grocery shopping Monday meant standing in long lines and waiting ... Shoppers came in families. Sometimes there were six adults in a car. They seemed to be shopping more from compulsion than need.By the end of the day businesses, public transportation, utilities and educational institutions had all closed, and deliveries of milk and cattle to the city had halted.

August 1 onward

On August 1, Mayor Maier issued an order relaxing the curfew to only night hours. Some people began returning to work and some public services became available, at least partially. Police responded to reports that youths were lighting a paint store on fire. Clifford McKissick, aged 18, was shot in the neck and killed as he fled toward the nearby family home. The Milwaukee County's emergency hospital was closed and all personnel were transferred to the general hospital, which was farther away from the city, and deemed better capable of coping with the large number of casualties. The ''Milwaukee Sentinel'' published a piece August 2 describing the plight of those who were restricted by the curfew, saying that they "were outside on their porches or standing next to their apartment buildings, watching. If they got too far away from their homes, though, police and guardsmen moved in." On August 3 the mayor postponed the curfew from 7:00 PM to 9:00 PM. On August 4 the mayor postponed the curfew from 9:00 PM to midnight, and announced that liquor stores and bars would be allowed to open and sell alcohol.Casualties and cost

In total, the riot resulted in three to four deaths (including at least one police officer), 100 injuries, and 1,740 arrests. According to stories published by the ''Milwaukee Journal'' on August 2 and 4, more than $200,000 in window damage had been done to businesses, and the cost of mustering and paying the National Guard to intervene amounted to nearly $300,000.Aftermath

On August 3, 1967, an alliance of civil rights organizations and male priest held a dinner to tribute Groppi to honor his contributions to the local struggle for racial equity in Milwaukee and the state of Wisconsin. On August 27, 1967, the localNAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

, led by Father James Groppi, held a march of about a hundred into a white neighborhood in protest of the city's housing laws. They came up against a crowd of 5,000 who retaliated with racial epithets

An epithet (, ), also byname, is a descriptive term (word or phrase) known for accompanying or occurring in place of a name and having entered common usage. It has various shades of meaning when applied to seemingly real or fictitious people, di ...

, stones, and garbage. The following day Groppi addressed a meeting of supporters at St. Boniface Church, and prepared them for what was likely to come:

If there is any man or woman here who is afraid of going to jail for his freedom, is afraid of getting tear gassed, or is afraid of dying, you should not have come to this meeting tonight.On August 29, the curfew was lifted and Groppi led 200 members of the Milwaukee

NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

on a march out of the ghetto and toward Kosciuszko Park, in an area predominately inhabited by white residents. The mob they met had grown to 13,000 and the protesters came under sniper fire as they returned to their headquarters. It was burned down later that night or early the next morning. The Mayor issued an order banning such demonstrations, and both Groppi and Phillips were arrested.

On September 4, Martin Luther King Jr. sent a telegram from Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

in support:

What you and your courageous associates are doing in Milwaukee will certainly serve as a kind of massive nonviolence that we need in this turbulent period. You are demonstrating that it is possible to be militant and powerful without destroying life or property. Please know that you have my support and my prayers.On September 17, Groppi made an appearance on Face the Nation. This was televised on CBS. In September, Dick Gregory had issued a formal boycott against Schlitz and many other brewing companies. On October 3, 200 demonstrators marched to Schlitz and Blatz brewery underline their protest. This was supposed to put pressure on the companies to gain support for open housing. On April 8 of 1968, 15,000-20,000 participated in a memorial march in downtown Milwaukee. On May 13,

NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

president and vice president Fred Bronson and Fortune Humphrey led 13 organizations and 450 people on a march to the Public Safety building to push for better police-community relations. A resolution was posted by Bronson and Humphrey that asked the mayor to lay off Chief Breier to "restore sanity" in police operations and to protect the black community from being controlled by a police force.

Groppi went on to lead 200 consecutive days of protests.

Father Groppi resigned as advisor to the YC in November 1968.

In 1968, Henry Maier was reelected for his 3rd term and received more than 80% of the total votes. This was the largest runaway victory that Milwaukee had ever seen.

On September 21, 1969, Groppi led a group of welfare mothers, low income African Americans, college students, Latinos and many others on a march from Milwaukee to Madison to protest the potential possibility of cuts for Wisconsin's state welfare budget.

Legal changes

In the immediate aftermath of the riot and marches, little was accomplished in the way of laws, policies, and programs. Speaking of the lack of available funding for enacting proposed reforms, Mayor Maier said:

In the immediate aftermath of the riot and marches, little was accomplished in the way of laws, policies, and programs. Speaking of the lack of available funding for enacting proposed reforms, Mayor Maier said:

The city of Milwaukee can no more finance the crucial problems of poverty, ignorance, disease and discrimination with the property taxes of relatively poor people than the city of Milwaukee can finance sending a man to the moon.However, later that year the mayor rejected federal benefits, as they required support for fair housing in the city. He argued instead that the problem was a county-wide one. Support continued to grow for a housing measure, supported by the

League of Women Voters

The League of Women Voters (LWV or the League) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan political organization in the United States. Founded in 1920, its ongoing major activities include registering voters, providing voter information, and advocating for vot ...

and local workers unions. A petition circulated by supporters of fair housing garnered 8,000 signatures. A petition that opposed such legislation was presented to the city council with 27,000 signatures. In December, the city passed a form of fair housing that included enough exemptions, that it only applied to about a third of the housing in the city. Groppi dismissed it as "tokenism and crumbs". Phillips voted against the measure, saying it was "very much too late with very much too little".

On April 11, 1968, a week after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr., an African-American clergyman and civil rights leader, was fatally shot at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968, at 6:01 p.m. CST. He was rushed to St. Joseph's Hospital, where he died at 7 ...

, the US Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washingto ...

passed the Fair Housing Act

The Civil Rights Act of 1968 () is a landmark law in the United States signed into law by United States President Lyndon B. Johnson during the King assassination riots.

Titles II through VII comprise the Indian Civil Rights Act, which applie ...

, as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1968

The Civil Rights Act of 1968 () is a landmark law in the United States signed into law by United States President Lyndon B. Johnson during the King assassination riots.

Titles II through VII comprise the Indian Civil Rights Act, which applie ...

. Faced with capitulation, or the violation of federal law, the Milwaukee Common Council

The municipal government of the U.S. city of Milwaukee, located in the state of Wisconsin, consists of a mayor and common council. Traditionally supporting liberal politicians and movements, this community has consistently proved to be a strongho ...

followed on April 30, passing an ordinance that was stronger than that required by the federal law. Casting a tie-breaking vote, council president Robert Jendusa said he hoped the measure might "heal some of the wounds of the community".

Public opinion

According to Nesbit, the riots "widened the gap between militant blacks and other civil rights activists and the uncompromising white majority in the city." Thomson described the disparate interpretations of the event, emphasizing that blacks tended to view it as "a violent expression of the accumulated frustration and anger, undesirable but understandable", while whites believed it represented "the failure of black parents to control their children, irresponsible and rebellious individuals and the agitation of civil rights activists..." Blacks tended to see solutions in public reforms and the advancement of civil rights, while whites tended toward the need for increased policing and gun control. In an article published August 1, 1967, by the ''Milwaukee Sentinel,'' an interview was reported with "John", an anonymous black rioter in his 20s:He's (the white man) out there marching up and down with his guns. Why can't we march up and down with our guns? ... We went before (Mayor) Maier and we argued and argued and argued and argued and argued and it didn't do no good...A study conducted by the Milwaukee

Urban League

The National Urban League, formerly known as the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, is a nonpartisan historic civil rights organization based in New York City that advocates on behalf of economic and social justice for African Am ...

found that, among blacks arrested during the riot, 90% cited "blocked job opportunities" as one of the root causes. The same study found that 53% of blacks arrested were unemployed or underemployed compared to 29% among blacks not participating in the riot. In another University of Wisconsin

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, t ...

study, 54% of blacks interviewed reported that police brutality had a "great deal" to do with the riot. Another 55% felt that lack of respect and insults by police occurred frequently in the ghetto.

According to a research conducted by Jonathon Slesinger, 24% of inner city blacks described this event as a civil rights struggle, while 43% of inner city whites viewed it as a riot. Opinions on how to avoid future disturbances varied between white people and black people. For the white inner city respondents, 51% wanted to give police more power so suspicious people on streets would be stopped and get searched. Of the inner city Black respondents, 84% favored a proposal that would reduce racial disparity and provide more jobs for black people.

Legacy

The Clifford McKissick Community School in Milwaukee was named for the black youth killed by police on August 2 as part of the riot. In 1981, his family filed a civil lawsuit alleging excessive force on the part of officer Ralph Schroeder in the shooting death of McKissick. A Circuit Court ruled in favor of the officer and found that McKissick was responsible for his own death. A year after the riots, John Oraa Tucker, a Shorewood High School janitor who lived in the house burned on the morning of July 31 (where Nelsen and a police officer were killed, among four others who were wounded) was charged with 9 counts of attempted murder. After the longest jury trial in Milwaukee County Court history (17 days of verdict deliberation) he was cleared on the most serious charges, but found guilty of endangering the safety of the public and given a 25-year sentence. He was paroled on July 1, 1977, just under 10 years into his sentence, and moved to Wausau, Wisconsin. Asked about the events and his convictions in an interview two weeks after his release, Tucker remarked "As long as people's minds are in the past, it puts bumps and obstacles in the way of the future. It's been a long time. Let's forget about it." In a 1970 case heard before theWisconsin Supreme Court

The Wisconsin Supreme Court is the highest appellate court in Wisconsin. The Supreme Court has jurisdiction over original actions, appeals from lower courts, and regulation or administration of the practice of law in Wisconsin.

Location

The Wi ...

, ''Interstate Fire & Casualty Co. v Milwaukee,'' a company sought $506.93 in damages done to a tavern during the riots. In its decision siding with the city, the court wrote:

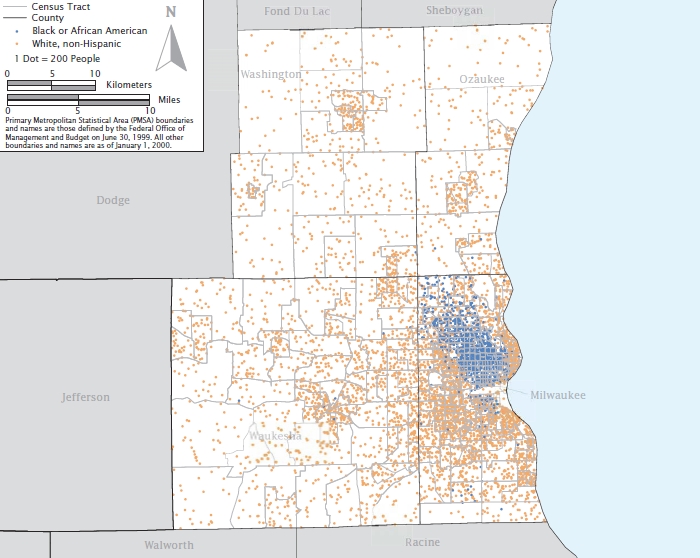

In this era of "confrontation politics", "protest marches", and "civil disobedience" it is naive to think that riot statues such as that before the court will retard such occurrences or keep them from developing into damaging riots, especially considering the spontaneity with which they occur.In 1980, twelve years after the passage of Milwaukee's equal housing ordinance, the city ranked second nationally among the most racially segregated suburban areas. As of 2000, it was the most segregated city in the country according to data gathered by the

US Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau (USCB), officially the Bureau of the Census, is a principal agency of the U.S. Federal Statistical System, responsible for producing data about the American people and economy. The Census Bureau is part of the ...

. In a July 2017 study by the Wall Street Journal of the nation's 100 largest metropolitan areas, Milwaukee was listed the 11th most segregated city.

See also

*2016 Milwaukee riots

On August 13, 2016, a riot began in the Sherman Park neighborhood in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, sparked by the fatal police shooting of 23-year-old Sylville Smith. During the three-day turmoil, several people, including police officers, were injured an ...

*List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

Listed are major episodes of civil unrest in the United States. This list does not include the numerous incidents of destruction and violence associated with various sporting events.

18th century

*1783 – Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783, June 20 ...

* Mass racial violence in the United States

Notes

References

{{Milwaukee 1967 in Wisconsin African-American history of Milwaukee African-American riots in the United States 1960s in Milwaukee Riots and civil disorder in WisconsinMilwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee is ...

July 1967 events in the United States

August 1967 events in the United States

White American riots in the United States

History of racism in Wisconsin

Housing in Wisconsin

Long, hot summer of 1967